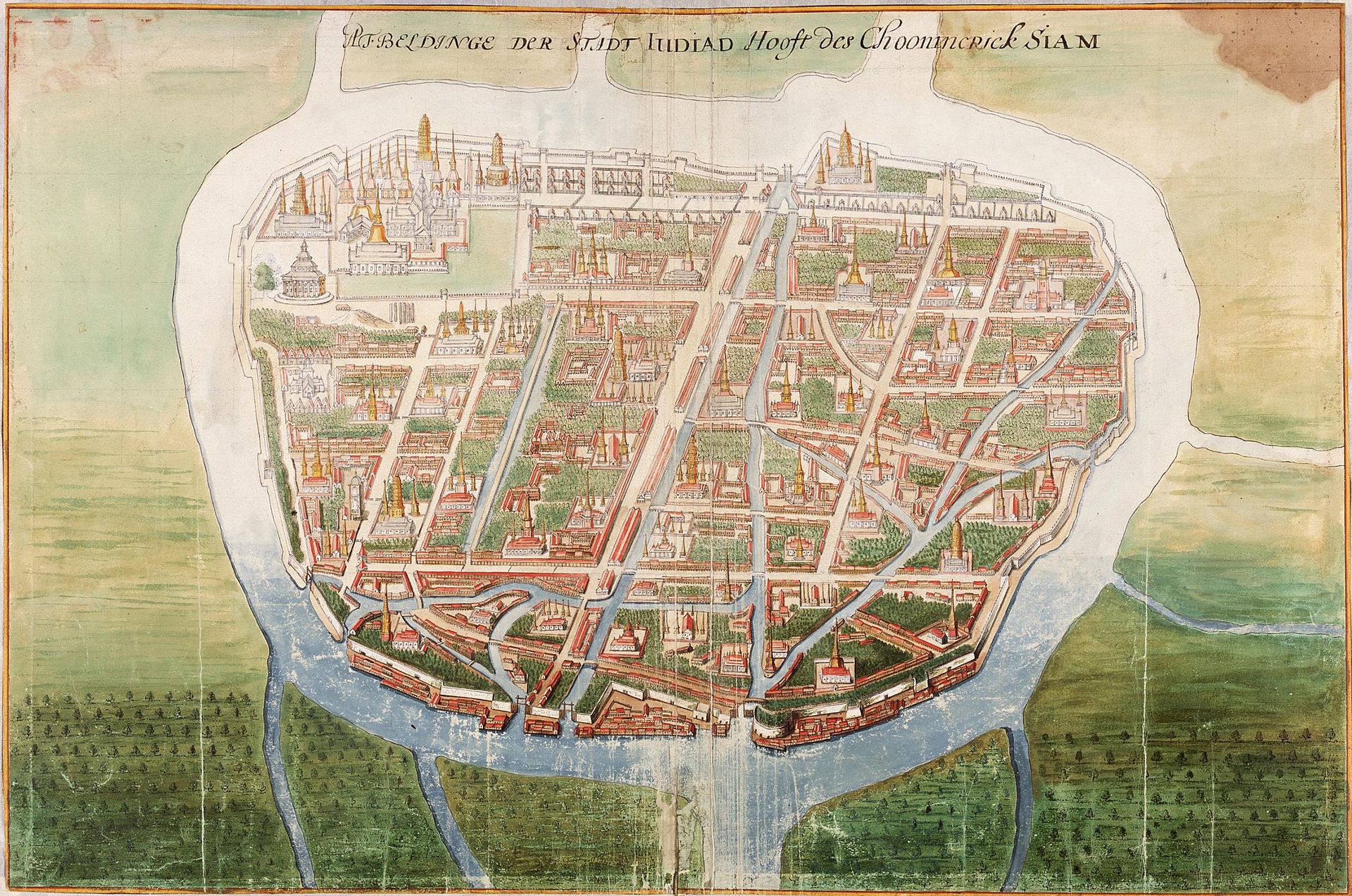

Pattani and Ayudhya (1612-1617)

The Company first investigated Siam, in 1612, after Dutch hostilities had reduced the profitability of the spice trade. Peter Floris and Lucas Antheunis sailed in the Globe to India’s Coromandel Coast, to purchase cottons, then to Pattani and Ayudhya. The Seventh Voyage lasted 4½ years, but the markets were not as buoyant as they expected. Siam was beset by rebellion and the threat of invasion, which depressed cotton demand even as the Dutch were adding to supply. The situation was made worse by some of the Globe’s men, who offloaded their private goods ‘50 per cento better cheape’ and so put a ‘dead markett … all under foote.’[4]

Ill-discipline extended to behaviour which was often disorderly. John Johnson became the Globe’s master when Anthony Hippon died of the flux, in July 1612. A short while after his son-in-law, George Ponder, was ‘drowned … or else devoured of a whale,’ Johnson refused to support his captain, Thomas Essington, against Ponder’s disobedient brother. Insubordination became a habit. It culminated in a contretemps, after Johnson refused to join a service of thanks for the ship’s delivery from a storm. Essington reproached him, and he took it ill,

… answering the Captayne very scornefull and injuriously, calling him rogue, rascall, dogge, and other suchelyke vile words, and rising att laste, stroke att him, and so were wrestling together till some came to parte theym; whereupon the Captayne caused him to bee nayled upp in his owne cabine …

Later, Essington was put on his guard: ‘Johnson was broke oute of his cabine, and had a naked dagger in his codpisse.’

Essington had his faults also. Within the year, he threatened to take the Globe to England, on the grounds that she ‘was very leacke, the men unwilling.’ This ‘verye foolishe peece of service’ was only avoided because his supporters were too few to raise her anchor. Yet Floris passed over Essington’s pranks in silence. The reason is clear: the voyage was short of officers. Only this can explain the decision to appoint Johnson as second at Pattani, in 1614. Floris had removed him to Bantam, in October 1613, but Thomas Best, commander of the Tenth Voyage, refused to take him to England. Instead, he returned him with ‘threatning words.’ Johnson did not remain in post for long. His final encounter with Floris was at Bantam, in 1615, where he asked to re-join the Globe as Master. Floris refused, as John Skinner had been serving in that capacity for two years. Floris wrote,

… notwithstanding that hee [Skinner] also was a greate drunckard and no friend of myne, I coulde not fynde in my harte to thruste him oute att this tyme and to receyve the other agayne.

By 1616, however, Johnson had become second at Ayudhya. John Browne reported he was giving entertainment to the Portuguese, ‘nott unto men of any credytt or fashonne but to the worst and most lewdest livers in Syam.’ This was just a few days after the death of Benjamin Farie, the factory’s chief, whom the Dutch said the Portuguese had poisoned. Johnson complained of Dutch ‘vipporous, scorpean toonges.’ He had goods to sell and, provided the Portuguese paid well, he would not ‘examen ther corse of life.’ The argument did not convince his associate, Richard Pitt. When Johnson died, in August 1617, he stated baldly that he was ‘the execusenor of his one life by his evell caredge’ and left ‘all busnes att seixe and sevfen.’[5]

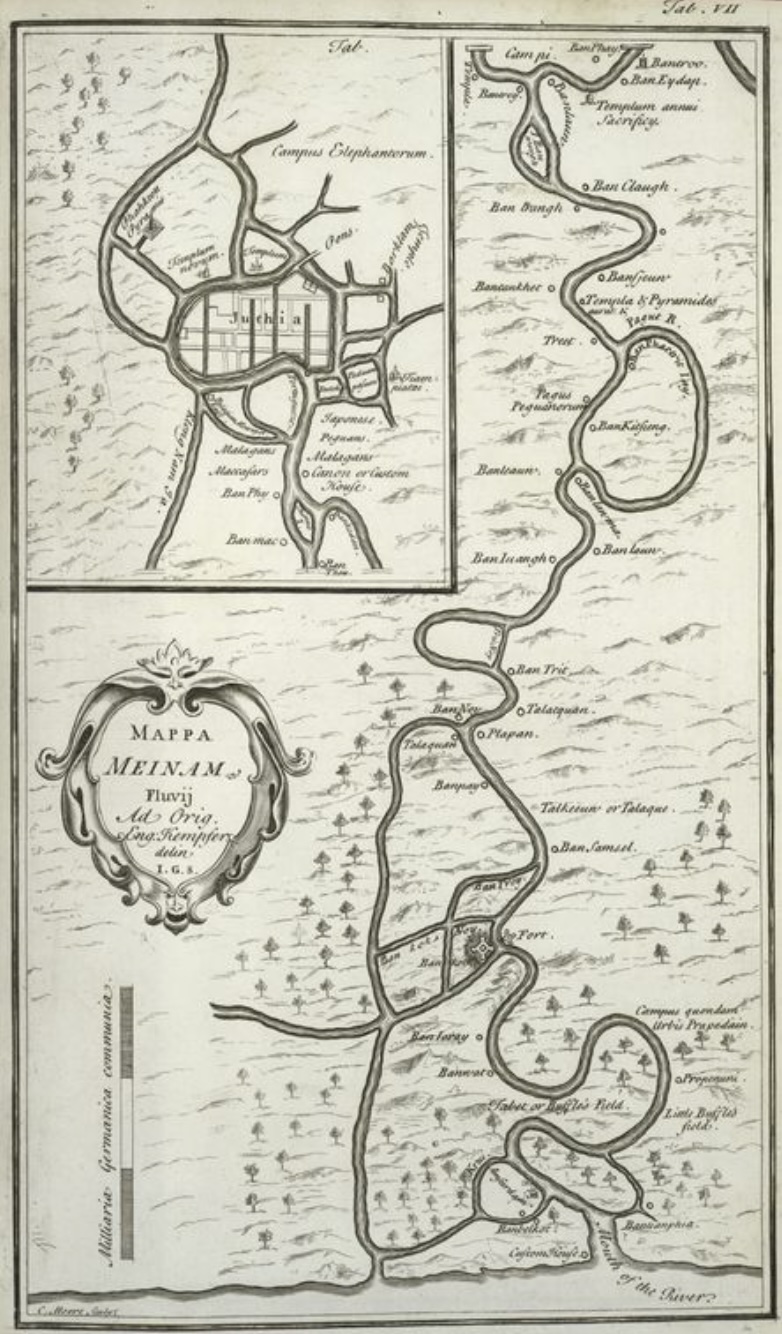

So, Floris and Antheunis had to think on their feet. They dealt with the glutted market by diversifying their points of sale. They tried Songkhla (‘Singora’), Cambodia and Macassar, but their great hope was Japan. This should not surprise, as their instructions had mentioned it. The traffic with Pattani was familiar to William Adams, in Japan, and to John Saris, the Company’s agent at Bantam, who sailed there, in 1613. Like Hirado’s Richard Cocks, they knew Melchior van Santvoort and Jacob Joosten, who travelled the route.

Within a few days of his arrival at Pattani, Floris sent letters to Adams on the Dutch vessel Greyhound. At the time, he considered the trade to be of small importance but, within the year, Lucas Antheunis, in Ayudhya, was writing optimistically of Japanese demand for sappan wood and deer skins. Two Japanese ships had arrived; their owners bought more cargo than they had room for, necessitating the purchase of two extra junks.[6]

In Japan, Richard Cocks co-operated enthusiastically. John Saris had been optimistic that sales of goods imported from Bantam and Siam would raise much silver and, before departing, he had instructed Cocks to buy a junk, like the Dutch. Cocks was happy to comply. Japanese demand for English cloth was slow and, for three to four years, the Dutch had been sourcing silk, sappan and deer skins from Siam and Pattani, ‘which is all ready money heare.’ In November 1614, Cocks purchased the Sea Adventure, to ply the route.[7]

She sailed four times, but the experiment did not prosper. Costs were high, the route exposed to storms. On her 1617 return voyage, she reached Tsushima, having lost thirty-four crew, her cables, and her anchors. William Eaton wrote, ‘Wee weare noe better than a rake in the sea.’ Outbound in 1618, she took shelter in the Ryukus, twice. The second time, she took a beating on a coral reef for a week and was nearly abandoned. The repairs took eight months. Just three days into the next stage of her journey, the sea became ‘so hie & loftey’ the mainmast worked loose, and the new woodwork separated from the old. Even with constant pumping, by the time the Adventure reached the Chinese coast, there were nine feet of water in the hold. Still, the crew stuck with her. They stopped her leaks, passed hawsers around her hull and, pumping furiously, reached Siam a whole year after departing Hirado. Only then was she stripped of her masts, sails, and cordage. They were transferred to a new vessel, which was sold in Japan.[8]

Originally, Cocks thought that crewing his junk with Japanese would be cost efficient. In fact, the crews were expensive, and the junk was too small. Later, he advocated that larger, English ships sailing from Bantam to Japan should collect Siam’s skins and wood at Pattani and sail them to Japan ‘as the Hollanders do’. William Eaton wrote to Sir Thomas Smythe, to the same effect. London did not listen. Cocks had little option but to persist with his effort.[9]

London persevered in its belief that English goods would find a market in Japan. In 1615, when the Hoseander stopped at Pattani, she took on no silk, skins or sappan. In 1616, the Thomas and Advice passed by Siam completely. Cocks complained that cargoes of ‘English gallipots, looking-glasses, table-books and thread’ would not sell, but it was not until August 1617 that the Advice shipped something more suitable. From this error, there arose many of the difficulties of Hirado, Pattani and Ayudhya. As Cocks complained, in January 1617,

… it is certen here is silver enough, and may be carried out at pleasure; but then must we bring them comodeties to ther lyking, as the Chinas, Portingales, and Spaniardes doe, which is raw silke and silke stuffs, with Syam sapon and skins; and that is allwais ready money, as price goeth, littell more or lesse…[10]

When the Sea Adventure left Ayudhya, in May 1617, nothing remained in its godown. An attempt was made to source trade in Cambodia and Champa, but Johnson and Pitt warned that, unless they were supplied with goods from India, or silver from Japan, the next time she would return unfilled. Cocks sympathised. Unfortunately, Dutch hostilities caused the ships which followed the Advice to be diverted to the Bandas. Hirado, Ayudhya and Pattani were forgotten, and the Sea Adventure could not fill the gap.[11]

Henry Forest and John Staveley in Burma (1617-1620)

That left Chiang Mai (‘Janggamay’), which Ralph Fitch had visited, and about which William Eaton expressed some hope, in 1617. Thomas Samuel and Thomas Driver were sent there by Lucas Antheunis, in early 1613. Two years later, it was captured by the Burmese king, Anaukpetlun. When he departed for Pegu with prisoners and booty, he took with him Thomas Samuel and his unsold goods. (Driver escaped.) [12]

Samuel died shortly afterwards, but an inventory was kept of his merchandise and, eventually, news of it reached the Company, at Masulipatam. As it happened, Lucas Antheunis was in charge. In September 1617, he sent Henry Forrest and John Staveley to Pegu to reclaim his property. So began the Company’s first foray into Burma.

Reaching Pegu in November, Forrest and Staveley were bidden to choose the ground on which to build a house. That they had to pay for it was disappointing; that they were confined within its walls until sent for (and until the king had received their present) only more so. There was further frustration because no one dared to push their suit forward with the king. Before long, the pair were writing that,

The Country is far from your Worships expectation, for what men soever come into his Country, he holds them but as his slaves, neyther can any man goe out of his Country without his leave, for hee hath watch both by Land and Water, and he of himselfe is a Tyrant, and cannot eat before he hath drawne bloud from some of his people with death or otherwise.

The king was keen on trade. Unfortunately, he detained the envoys until March 1618, declaring they might not leave until the English sent some ships. In desperation, Forrest and Staveley wrote:

… the mony wee brought with us, it is all spent, and wee are here in a most miserable estate, and know no way to helpe our selves. For the King hath neyther given us any of our goods, nor leave to recover none of our debts, nor taken our Cloth, but wee are like lost sheep, and still in feare of being brought to slaughter. Therefore we beseech you and the rest of our Countrimen and Friends to pittie our poore distressed estate, and not to let us be left in a Heathen Country, slaves to a tyrannous King.

To maintain themselves, they sold some goods, the proceeds of which they supplemented with borrowing. Then, in April 1619, their house burnt down. The timing was unfortunate, as the country was disturbed by some sort of plot. The King, ‘incensed against one of his cheife nobles, executed him and diverse others.’ Forrest and Staveley missed the monsoon, and it wasn’t until April 1620 that they eventually reached safety, after being ordered out.

William Methwold, chief of Masulipatam between 1618 and 1622, does not give them much of a write-up. They were ‘royotous, vitious and unfaithfull,’ Forrest ‘a vearie villane, debaucht, most audacious and dishonest.’ He forwarded them, with their books, to Jakarta but warned ‘their accompts were forged at sea,’ the originals having been cast overboard ‘least coming to light they might have disclosed all their untruths.’ To Masulipatam, Forrest and Staveley brought Anaukpetlun’s offer of free trade, together with a ruby ring, two mats, two betel boxes and two pieces of damask. Methwold suggested it was ‘not impertinent to send a small ship to some of the King of Pegues portes, being that Kings special desire,’ but London was unpersuaded. By 1620, the Dutch were making life in the Indies extremely difficult.[13]

The Battle of Pattani to the Amboyna Massacre (1619-1623)

Floris and Antheunis’s voyage made a return of 218 per cent, but its real legacy lay in the establishment, in 1616, of the factory at Masulipatam, on India’s east coast. To Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the VOC’s choleric governor in the Indies, who complained of the way the English ‘followed us from Jakatra to Jambi, Pattani, Siam and Japan,’ Masulipatam was a step too far. It was a source of the goods most in demand in the Spice Isles. By April 1619, when John Jourdain sailed from Bantam with two ships to re-establish ‘the allmost decayed factories of Jambee, Potania, Siam, Sackadania, &c,’ the English and the Dutch were at war.[14]

Jourdain arrived at Pattani to find all in disorder ‘by the base and idle carriage of Edward Gillman.’ The factory’s stock had been ‘riotously consumed’ and nothing could be made of the accounts. Jourdain prepared to take Gillman in disgrace to Bantam, when three Dutch ships appeared. He might have escaped, but he remained ‘to avoyde the censure of the country people.’ George Muschamp wrote,

We had not then 5 peeces that would beare with them. They brought 6 demy-cannon of brass to play uppon the half deck, which kild and hurst most of us that were there, so that in the continuence of 5 glasses there was kild in the Sampson 7 English, 5 blacks and about 30 hurt, which moved the President to a parle, and talking with Henreek Johnson there commander, received his deathe’s wound with a musket under the hart. The Hound had 2 men kild and 16 miserably burnt with poulder.[15]

The English claimed that Jourdain (‘the President’) was deliberately killed under the white flag, the Dutch ‘without any special ayme at his person.’ No one knew that, in Europe, a Treaty of Defence had been agreed. When the news reached Batavia, the two sides agreed together to blockade Bantam, to prey on Portuguese shipping at Hirado, and to invest Manila and Macao. These operations occupied the Company’s ships between 1620 and 1622. The rewards fell far short of their cost (Richard Cocks’s share was £10,000 annually) and the vessels so employed were unable to supply the subordinate factories with stock. London had assumed that Coen would restore the ships and cargoes seized in the war. They underestimated his purpose.[16]

Given the treatment meted out to them, the factories at Pattani and Ayudhya had little chance. After 1619, they received next to no capital or goods. In June 1620, the Batavian Council decided to close Pattani, ‘unlesse we could bring downe those excessive presents accustomed to be paid there.’ By July 1621, its factors were complaining ‘we owe a great deale more than wee have in the house to pay.’ By December, the Siamese were anticipating closure, because the godown had fallen into disrepair, and because no English ships were visiting. In February 1622, according to Jourdain’s nephew, there were ‘not fiftie rialls in the howse.’[17]

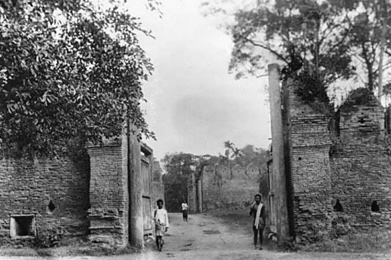

Syriam (1647-1657)

The Amboyna Massacre coincided with the closure the Company’s factories east of Java, and its concentration on trade between Western India and the Persian Gulf. Trade with Siam and Burma became the preserve of private merchants. It remained so until the late 1640s, when, as a result of the wars in Turkey, the Gulf trade ground to a halt. With that, the Surat council resolved to send shipping to remoter parts.[18]

In September 1647 – in the teeth of opposition from Masulipatam’s private traders – Thomas Breton, Richard Potter and Richard Knipe were despatched on the Endeavour to establish a factory at Syriam, near Yangon (Rangoon). Their first communication, of 1 January 1648, summarised their challenges:

Wee found the country standing distractedly amazed at the civill warr that then was in Ava (the metrapolis of this kingdome) betweene the King and his eldest sonn, not knowing which party to take, till it pleased God to give victory to the King by the slauter of his said sonn, who had determined his death; which was not believed in Sirian till the middle of December, when there begun to be againe corrispondence betweene it and Ava …

Their sales, they said, promised a profitable voyage, but they attracted customs of 16½ percent, in specie, with a strictness not seen elsewhere. Worse, without permission from Ava (two months’ journey away), they could not reload the Endeavour for their return, and the local agents would only trade after goods had been entrusted to them for seven months. Further costs ‘in this reported (but not truly cheape) country’ arose from the need to put the Endeavour into dry dock ‘to keepe her from the wormes.’ By then, the climate had carried off her master, her chief mate, her surgeon, and the beer with which the survivors might have drowned their sorrows had run out. Worse followed. Breton and Potter’s next missive told of a deplorable disaster on the way to Ava. One of their boats caught fire during the preparation of dinner, and much of their cargo was lost:

Of what necessaries wee had of our owne wee are utterly stripped, even to our dayly weareing clothes, not haveing left us anything to lie upon in this wilderness save the bare ground … The ruines of what wee have left, though of very little vallue, yet wee conceive them worth the carriage to Ava; but such is the cruelty of these people that, seeing us in necessity of a boat, will not be hired to furnish us for less than 500 usest; which, though it sinck deep into the worth of our burnt goods, yet is better given than that they should be altogether lost.

PS… Forgot formerly to advise that on January 23 Richard Manly … fell overboard and was drowned.

In the end, persistence paid off. ‘Rejoice that the representations from Masulipatam against that venture were not listened to,’ wrote Thomas Ivy from Fort St. George. Sales came in at three times their cost, which could not but ‘give the Companie good incouragement for the prosecuteinge of the Pegue trade.’[19]

After a second successful voyage (the Dove in 1650), the Ruby was fitted out especially for the Syriam route. She made successful crossings in 1650-1651 and 1652-1653. Then, with the outbreak of the Anglo-Dutch War, the trade fell victim to Holland’s naval superiority. The prices received for the Company’s goods fell, because of their de-based quality, and the goods they sought became more expensive, or, as with bell-metal (‘ganza’), tin and ivory, unobtainable, because of a government ban on sales. Optimism evaporated. Fort St. George complained that ‘our Pegu friends complied not with the ½ of what wee expected of them.’ With pressure building on the Company’s finances (as a result of the war) and its monopoly (because of Cromwell), the decision was taken to close Syriam down.[20]

The instruction was issued in October 1655. It was not implemented until 1657. Those responsible protested they had the best of motives for delay. They said,

Those ffactors in Pegu had made soe many debts and have put you to soe much charge in bilding houses, dockes and other accomodacon that if wee withdrawe the ffactors all your previleges debts and accomodacon will be lost.

They claimed to have secured a large quantity of ganza, and to lack only a vessel to freight it. But they had selfish reasons for stalling, and long after official closure, an establishment of a sort remained. When, in 1680, Streynsham Master re-opened negotiations with Burma, Fort St. George instructed him to retake possession of ground and buildings which, they said, had been used by ‘strangers’ for some years past.

The ‘strangers’ were men like William Jearsey, Francis Yardley and Sir Edward Winter, officers of the Company long zealous in private trade. Jearsey and Robert Cooper had been ordered to return to Madras, with the ganza, on a Dutch ship, in 1655. Cooper returned, but without the metal. Jearsey insisted on using the Expedition ‘for the credit of the Nation … beeing an English ship.’ She was English but she was also Edward Winter’s. Inevitably, she missed the monsoon. When eventually Jearsey reached India, he gave Fort St. George a wide berth. He forwarded the books on the Dethick and, from them, President Greenhill discovered,

… a great part of [our Pegu Remaines] expended in his stay there, contrary to order, besides £100 in ready money taken thereout on accompt of his small wages, which disorderly proceeding, wee noe way approve of.

After the reorganisation of the Company under Cromwell, an order was issued for the arrest of Jearsey and Winter, and a ship of Winter’s, the Winter Frigate, was seized. But the clampdown on private trade was half-hearted. Too many of the Company’s servants were involved to permit otherwise. For twenty years or so, the interlopers went unmolested.[21]

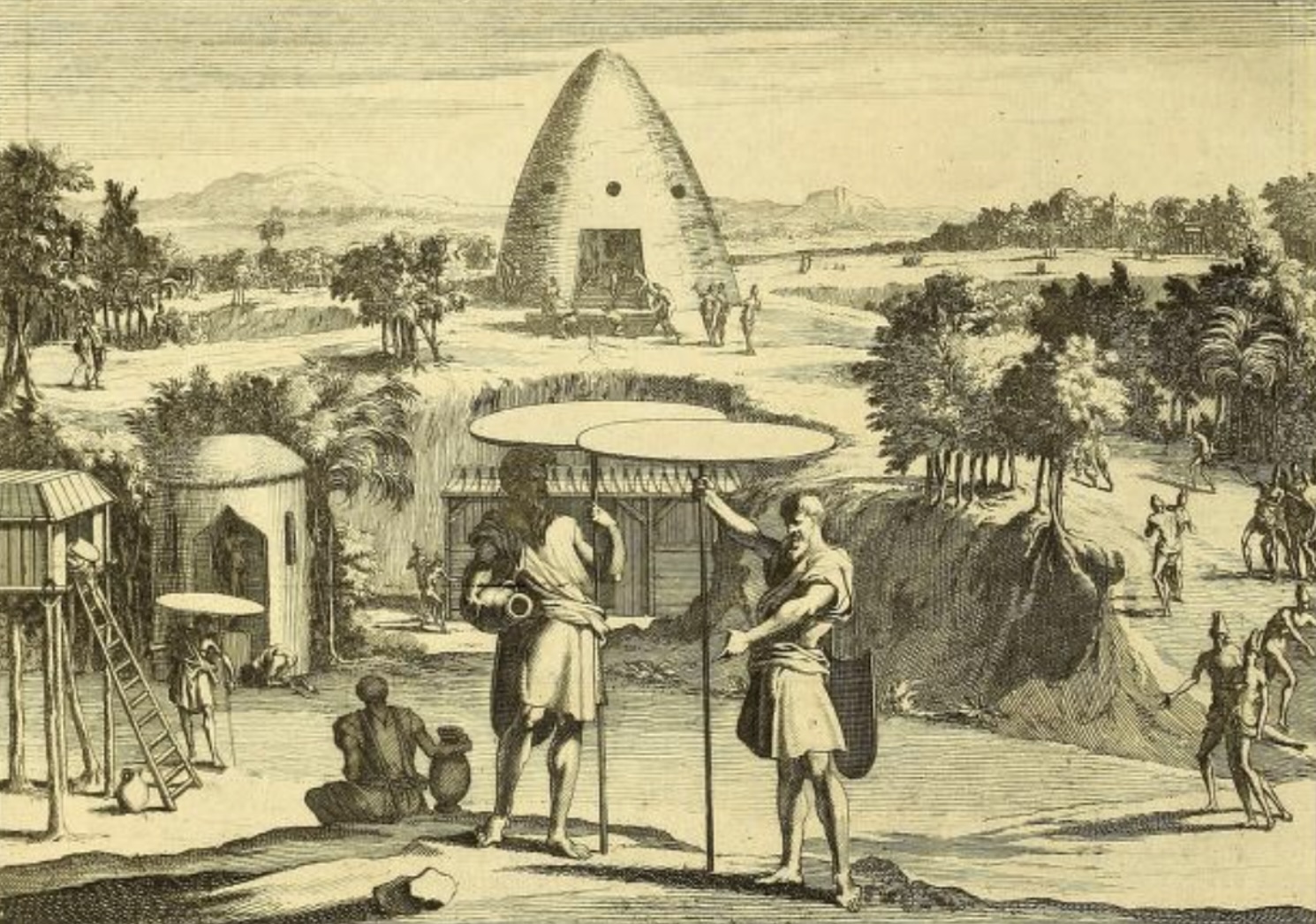

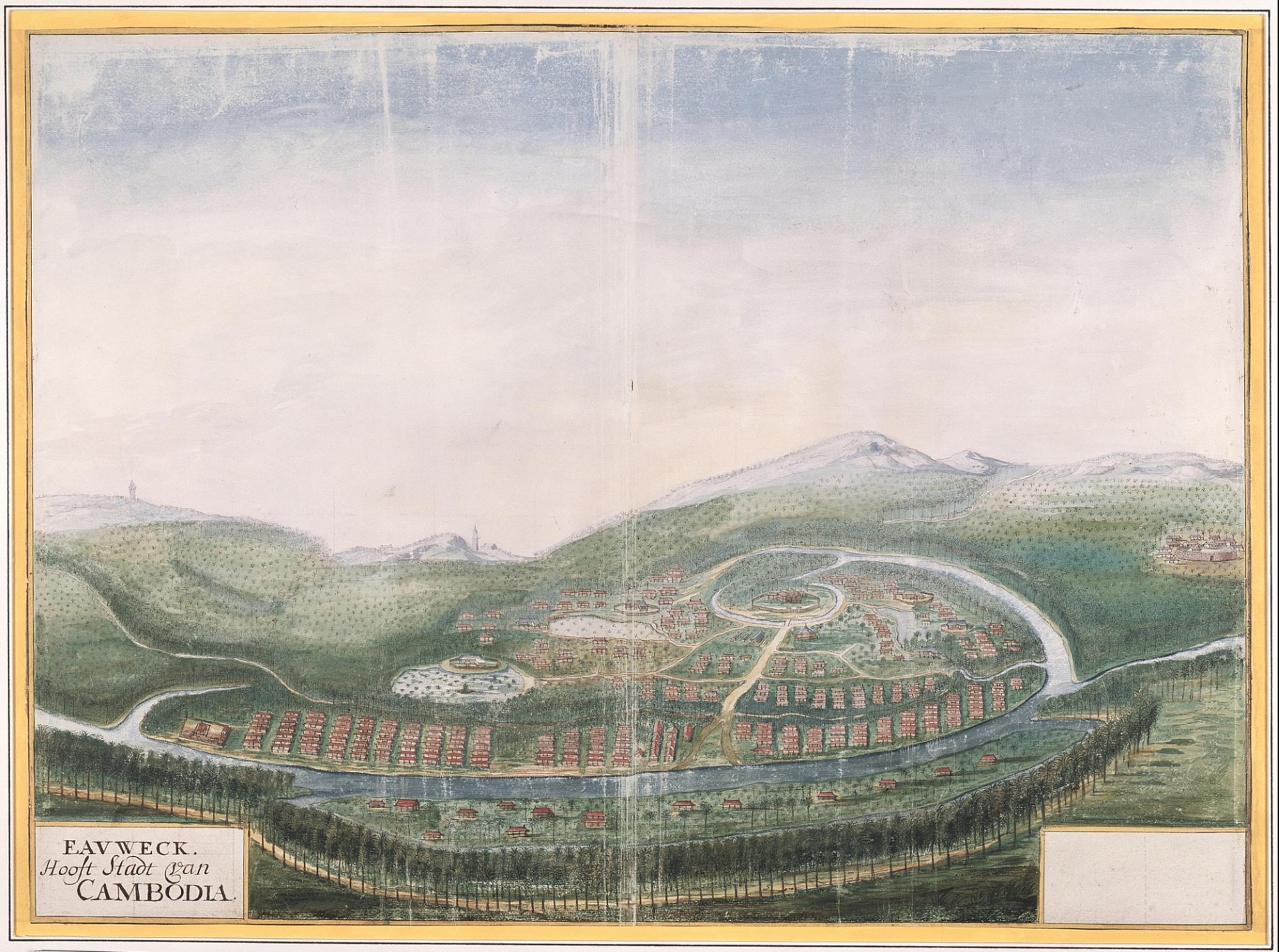

Cambodia and Siam (1654-1675)

The Company’s attitude to Burma was at one with their views on Cambodia and Siam.

When, in February 1654, the Directors heard that Aaron Baker, president at Bantam, had opened a factory in Cambodia, they expressed their ‘admiration’ that it had been set up without their ‘privitie or allowance.’ They told him his stock would have been better employed in India. Three months later, Baker’s replacement, Frederick Skinner, was told to close the factory down.

It is true that, when the Cochin-Chinese invaded Cambodia, in 1659, there were some Englishmen there who escaped from there to Siam. However, the ship which conveyed them, the Little Fortune, was engaged in private trade, not the Company’s. When Skinner was recalled to England to face embezzlement charges, John Rawlins (one of the refugees) admitted her cargo belonged to Skinner and himself.[22]

In 1661, John Bladwell took the Company ship Hopewell, with a quantity of private goods, to Ayudhya, after missing the monsoon for Macassar. Her stay was so unprofitable that Thomas Coates, a supercargo, and John South, a private trader, were required to remain behind, as security for the voyage’s debts. South cursed Bladwell for creating a ‘stinke in the nostrils of all nations,’ but he was alert to the opportunity his circumstances presented. To John Lambton, at Surat, he wrote,

Now lett me advice you, as a perticular friend, except you have such necessary occasions of keeping both your brothers with you, you will shipe a verie greate fortune for one of them if you cann gett him Seacond heather, to bee setled heere … & believe mee (God sendinge life) he will gett a greate deale money & not such lyke in all India, especially now at the begininge, & I take your brother Richard for a notable plodder & quicke & very fitt for this place, and the Company’s accompts here will not be a trouble at all …

London did not learn of their Ayudhya ‘establishment’ until October 1662. In February 1663, they wrote to Madras reiterating their policy of pursuing ‘a full trade out and home, without dispeircing our estate, in setling of new and unecessary factories.’[23]

In response, it was objected that the Dutch were loading twenty shiploads of Siamese goods a year, but the Directors knew that these were principally cargoes for China and Japan, where the Company had no outlet, and provisions for Dutch establishments elsewhere. Siamese demand for English manufactures was insufficient to make the trade profitable. When, in 1663, Sir Edward Winter sent the Madras Merchant to Siam, arguing there was insufficient cargo to justify a voyage to England, the Directors were highly critical. They believed she carried Company calicoes to be sold on private account.[24]

In December 1664, George Foxcroft was sent to replace Winter. London was convinced that the Siamese factory had been ‘sett up for perticuler interests and profit.’ Winter was told to account for the voyage of the Merchant ‘that wee shall bee noe loosers by it.’ When the Directors learned that they received £240 for freighting his goods, and paid £2,800 for demurrage, they required him to absorb the loss. Bluntly, they declared that ‘for setling a Factory at Syam, at present wee have noe resolution or encouragement, and therefore wee forbidd the same.’ They did not get their desire. In September 1665, Foxcroft was imprisoned by Winter, who remained in control of Fort St. George until August 1668.[25]

Earlier, in January 1664, he had informed London that the Merchant’s Robert Dearing was staying behind in Siam ‘to looke after the goods & your Woorships’ freight.’ Two years later, he wrote admitting that many were ‘dubious of his intentions to come hither.’ In fact, Dearing had died, in July or August 1665. By then, the factory was owed 25,000 rials. Dearing’s solution had been to borrow money from the king to tide things over. As soon as he got a sniff of this, Winter’s overriding priority became to recover his investment before the king recovered his loan.

In March 1665, William Acworth arrived in Tenasserim. A supporter of William Jearsey, who then led a faction against Winter from Masulipatam, he had sailed to escape the ‘unhapie differences at the Coast.’ It was his misfortune, therefore, to encounter Jonathan Stanford, who had been ‘inordered by Sir Edward Winter to receive his parte of the Madras Merchant’s cargoe.’ Together, in heavy monsoon rains, they crossed over to Ayudhya, arriving in July, just as Dearing started to sicken. Dearing’s last act was to send Stanford away,

… with a considerable quantitye of goods and money, takeing all the goods he bought at unreasonable rates, nay six hundred cattees or thirty thousand pieces 8 of the King at 2 per cent per month interest, consigned it soly to Sir Edward.[26]

Perspicaciously, Acworth saw that Dearing’s parting gift would ‘adde fewell to the fire.’ Within a few days, he was served with an order of possession on the factory.

Most of those to whom Dearing had advanced loans were Portuguese. When one of these was found murdered, his compatriots told Siam’s senior minister (phrakhlang or ‘Barcalong’) that Acworth was responsible. The Portuguese were taken at their word. Acworth was imprisoned for twelve days and one of his servants ‘cruelly marterized beyond relation.’ A factory coolie was treated less leniently. He ‘had all his bones broken, sharp pinns run under the nayles of his fingers and toes.’ His fingers then ‘rotted off.’

When he received Acworth’s account, Jearsey sent Francis Nelthorpe to stop Winter from ‘fingering any more of that adventure.’ Sir Edward countered by despatching Francis Brough, who captured Nelthorpe and took him, in irons, to Tenasserim and thence, in a junk full of elephants, to Madras. (Nelthorpe escaped, by jumping overboard.) Sir Edward’s defence was that he was taking care of his proportion in the joint voyage ‘& if the rest did not soe it was there owne fault & not his.’[27]

By April 1669, Foxcroft was back in charge at Fort St. George. In a report to London, he drew a line under the affair,

Mr. Deareing being dead at Syam, as it seemes poysoned by a black servant he trusted as a scrivener, & in his business possessed himself at his death of the factory & all that Mr. Deareing had in his power & possession, raised himself thereby from a poore fellow not worth a fanam to a great estate, & after dyed alsoe himself; and what between a brother of his & the Portigalls, these have made such havocke that it is much to be doubted that there will be a totall loss of whatsoever Mr. Deareing had of his owne & other men’s in his hands …[28]

To William Jearsey, Foxcroft wrote,

… we can say little more to the business of Syam but that for the present we cannot see the interest the Company hath there, & it being in such a low and bleeding condition, can require the settleing of a factory there for them.[29]

London concurred. Trade across the Bay was left to the private merchants. One of these was Samuel White’s brother, George.

George White and Constant Phaulkon Get Established

George first appears in the records in 1670, as a merchant of Masulipatam ‘not in the service of the Honourable Company,’ on the Consent, a ship that belonged to William Jearsey. Thus are his credentials established. In December 1675, he was in Ayudhya, where he encountered Hamon Gibbon and Benjamin Sangar of the Return.[30]

In 1672, she had been sent from Bantam to Taiwan and Nagasaki in quest of trade with Japan. However, she received a rebuff and, having obtained meagre pickings in Macao, she sailed to Siam to shelter from the Dutch. There, some of the crew were seduced by their kind reception to remain and ‘make the best of a bad market.’ They deprived the Company of flexibility by borrowing ten thousand rials from the king to fund the purchase of an onward cargo. This became a millstone.

Gibbon wrote to Gerald Aungier, at Surat, in terms that revealed that he had overcommitted his employers. Acclaiming a licence to buy commodities, including tin, he admitted they were ‘so farr engaged’ that they could ‘not come off.’ His books were unintelligible. Aungier assured London that Siam’s king would ‘deny you nothing that you can reasonably demand’ and that he might secure free trade with Japan. In Bantam, Henry Dacres was sceptical. He informed the Directors that he intended to close the operation. Then Sangar persuaded him to retain it until London’s desire became clear. Even so, Dacres assigned jurisdiction to Surat, claiming that nothing in his godowns would interest the Siamese. With some delicacy, he sent a cargo, half in woollens, to settle the king’s credit and a letter explaining that,

The greatest encouragement to induce the Company to continue a factory in your Majestie’s kingdome will be the hopes of vending of large quantities of broadcloth &ca English manufactores …

Dacres knew that Taiwan and Tonkin had been the entrepôts selected by the Directors for Japan – trade which he had decided was already ‘frustrate’.

When London heard of the factory, in October 1676, they shared Dacres’ scepticism. They wrote,

We have perused the copies of the letters from Syam and doe join with you in the resolution you have taken to dissolve the factory, which, if you have not already done, wee would have you effect without further loss of time, beeing wee cannot expect by it considerably to increase the consumption of our native manufactures.[31]

It was only after Dacres’ inexperienced replacement, Arnold White, was persuaded that woollens would sell in Siam that London allowed their judgement to waver. He was unwise but, by the time he was murdered, in April 1677, London was committed. In July 1678, the Tywan left Bantam with a cargo of English goods and twenty thousand silver dollars. With her sailed Richard Burnaby, to replace Gibbon as chief. His task was to resolve ‘severall great enormities’ brought to light by the Return’s Samuel Potts.[32]

For the interlopers, Siam’s attraction was that it lay at the fulcrum of trade between India and Japan, a portion of which missed Malacca’s straits by crossing the isthmus between the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand. As George White explained, an issue for King Narai was that the trade had been ‘totally engrossed’ by Persians and Moors from Surat and Coromandel. (Their interest had been promoted by Aqa Muhammad, a favourite opposed by the phrakhlang.) Here was an opportunity. Narai might reassert himself by bringing the Company to bear, which would also provide a counterweight to the Dutch, who had wrested from Siam the sea trade with Japan after their blockade of the Chao Phraya River, in 1664.[33]

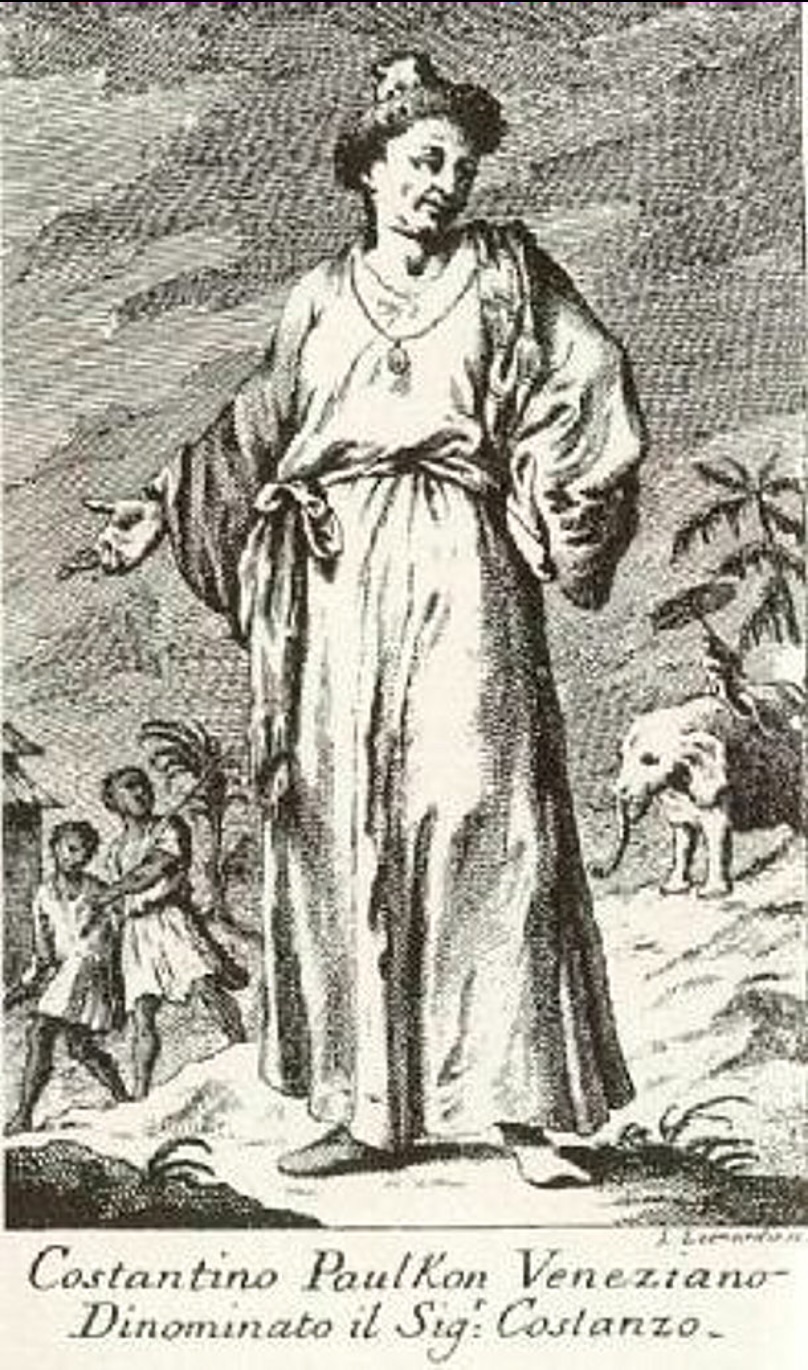

Yet White involved the Company for his own purposes. Soon he was collaborating with Burnaby and his servant, Constant Phaulkon, a Malay-speaking Greek, from Cephalonia.

On his arrival, in October 1678, Burnaby reported he was received ‘with an abundance of satisfaction and content.’ There was no such abundance in the warehouse: just a few remains, and those ‘very inconsiderable’. Sangar (now dead) had kept the books on loose sheets of paper, and Gibbon in ignorance. Some of the pages had been secreted away by William Ramsden, the factory’s second. Such stocks as existed were mostly claimed by Ralph Lambton. Reaching Siam from Surat, he had found a Company ship unloading a similar cargo. Sangar placed Lambton’s goods under the Company’s care until prices improved. He also supplied him with some tin, which Lambton bought with the Company’s cloth. Other stocks were claimed by Ralph’s brother, Richard. The records were confused, the arguments between the Lambtons and Burnaby protracted.[34]

Faced with these difficulties, Burnaby became ‘very short in his advices.’ White was employed as his second and Phaulkon was deployed to work with the phrakhlang. The old story is that he earned favour by rescuing a Siamese ambassador with whom he had been cast away in a storm. In fact, he was wrecked whilst running guns to rebels in Songkhla. Burnaby offered Phaulkon, with financial inducements, to draw attention away from his own role in the operation. Phaulkon quickly revealed the scale of the cut that Aqa Muhammad had enjoyed from the king’s trade. Profits doubled and the phrakhlang was delighted.[35]

At the turn of 1680/1681, Gibbon and Potts sent Bantam a litany of complaints against Burnaby and White: goods which might have been used for repaying debts had been diverted to private cargoes; company cloth was sold to Phaulkon at cost and resold, at great profit, to merchants from China and Japan. Potts added a charge of assault against Burnaby. Demanding £10,000 in compensation, he claimed, ‘I cannot with security act in the behalfe of the Honourable Company for feare of being murthered.’

Bantam sent George Gosfright to examine the situation. In January 1682, he charged Burnaby with embezzling large quantities of copper, tin, and cloth, and of using the Company to subsidise his, and Phaulkon’s, losses. Burnaby’s claims against the Lambtons were ‘full of rank mallice & injury,’ his abuses of Potts ‘intollerable’. Potts’ allegations against White, who had quit in 1680, were judged unproven, but Burnaby was dismissed and summoned to Bantam.[36]

Samuel White, meanwhile, was piloting the king’s ships between Mergen and Coromandel. Not infrequently, he transported elephants to Golconda, for deployment in its wars. Their conveyance required skill, and White acquitted himself well, whilst also performing service for the interlopers of Masulipatam. Samuel Wales, its chief, wrote of his transporting ‘concernes of Mr Hatton’s, Mr Tivill’s and Mr Wynne’s in copper, also 70 chests of copper of Mr Matthew Mainwaring’s.’ These actions angered the King of Golconda’s governor, Ali Beague, whose sympathies lay with the Persians of Tenasserim. Late in 1681, he denied Samuel some ship’s cables. White was caught in a storm, ‘cast away upon the Coast’ and feared drowned. This had repercussions later.[37]

London was upset also. Despite their efforts, and because of Burnaby’s, their premonitions about Siam had come true. They ordered the factory closed on 26 November 1679, on 19 March 1680, on 25 August 1680, on 5 January 1681, and on 28 February 1682, when they ordered Burnaby sent to England under safe custody. Amazingly, in September 1682, Bantam returned him to Ayudhya. They said it improved his chances of repaying his debts. He departed two days before a ship arrived from London to collect him.[38]

When Gosfright returned to Bantam, he left Potts and his colleague, Thomas Ivatt, in charge of the factory. Still, he judged them ‘of a fretful peevish temper.’ Quickly, they fell out. Ivatt claimed that Potts’ approach to debt recovery brought the Company no credit. Certainly, he seems not to have appreciated that, without Phaulkon’s co-operation, he was unlikely to recover anything of significance. Ivatt moved into Phaulkon’s house, with Burnaby.

In June 1682, Phaulkon accused Potts of going,

… from one house to another laden with rayleries & defamacions, endeavouring to staine my creditt & reputation with scurrilous & scandalous reports, not becoming a person in your quality, severall times making your complaints to His Highness the Barcalong, which savoured more of mallice & envie than it did of reallity …

Claiming Potts had painted him ‘as odious as your own foul mouth which reported it,’ he demanded compensation, for defamation.[39]

Next, Ivatt and Burnaby charged Potts with counterfeiting Burnaby’s signature, to have his possessions delivered to the Company’s godown. Potts wished to get them into own his hands, Ivatt claimed, ‘haveing takeing out already two peeces to satisfie one of his perticuler debts.’ In December 1682, the building burned to the ground, an event which Burnaby ascribed to Potts, and ‘the carlessness & debauchery’ of his colleagues. Denied the chance to rake through the ashes to recover his ‘treasure’, he assigned to Potts the liability for any sums that he might owe the Company. Implausibly, he wrote that ‘those chests which [Potts] fradulently tooke & kept from mee [were] sufficient to have discharged all demands.’

In his New Account of the East Indies, of 1727, Alexander Hamilton agreed that Potts was culpable. He claimed that, through riotous living, he burned his way through the Company’s money, and so resorted to various ways of cooking the books:

The first was on 500 Chests of Japan Copper, which his Masters had in Specie at Siam, and they were brought into Account of Profit and Loss, for so much eaten up by the white Ants, which are really Insects, that by a cold corroding liquid Quality, can do much Mischief to Cloth, Timber, or on any other soft Body that their Fluids can penetrate, but Copper is thought too hard a Morsel for them … But that small Article of 2500 Pounds, went but a small Way towards clearing of his Accounts. So after Supper one Night as they were merrily carousing, the Factory was set on Fire …

The counterargument was that the arson had been arranged by Phaulkon to destroy Potts and the evidence for the money which had been siphoned from the Company’s coffers. This is what Strangh came to believe, though he confessed he could not prove it as a ‘matter of fact’. Potts claimed he could produce a ‘whole toune’ of witnesses to support his case. Just one ventured forth. He ‘proved drunck & nott one word of sence to bee gott out of him.’ In 1686, the Company judged Potts ‘the faithfullest of all those we employed formerly at Syam.’ He later served as chief in Indrapura, although he was charged by some, including Hamon Gibbon, with bringing its affairs to ‘distraction’. [40]

In Siam, it seems, Potts rose to a responsibility he was ill-equipped to manage. Caught in a web of debts between Company and king, he denounced the sharp practice being perpetrated about him. Phaulkon he described as a ‘bramble’ to be rooted out, unless the Company wished to surrender themselves to his mercy. When, after he had transferred his allegiance, Ivatt offered to help clarify the factory’s accounts, Potts responded,

… as great lyars need good memoryes soe malitious persons need good inventions, and give mee leave to tell you hee that goes by hearsay without produceing authors may well bee stilld an incendiency of the Devill.

At one point, he was arrested and exposed publicly in the stocks on the unlikely charge that, when he neared Phaulkon’s house to pay for a butt of beer, he was really ‘waylaying to murther him.’[41]

In December 1682, the Directors sent William Strangh and Thomas Yale on ‘a last experiment’ to establish whether their losses had arisen simply ‘from the ill administration of those false and negligent factors we had the misfortune to imploy, especially that wicked Chief Burnaby.’ Were it so, it seems they were willing to reverse their decision to close the factory.[42]

When he arrived, Strangh hardly knew which way to turn. His accommodation was ‘a meere doog hole, more likely to a prisson then a dwelling place.’ When he first ran into Burnaby, whom he did not recognise, and whom he believed to have been deported, Phaulkon inveigled him into declaring he was being severely handled in London, before making the introduction. Potts retreated to a houseboat on the river, from which he refused to stir. His place was taken by Gibbon, whose constant, illusory refrain was that Phaulkon would be disgraced the moment a complaint was made against him. Yale consistently undermined Strangh’s position by taking an opposing view. Even so, it took Strangh nearly two months to decide that Phaulkon had monopolised for himself the trade of the English. The fiction that the Company might export whatever they wished was finally made transparent when merchants from China and Portugal declined to treat, for fear of reprisals. Phaulkon issued a threat, forbidding Strangh from interfering with the interlopers whose trade he was engrossing for himself:

Hee tould mee absolutely that should effect nothing in this place before did give onder my hand (which iff would not should bee compelled) that should not wreitt to Surratt or the Coast anything to the prejudice of those gentlemen from both those places that had shipt goods for Syam this yeare ….[43]

To Strangh’s considerable frustration, whenever he tried to engage the phrakhlang, Phaulkon interposed himself. On 28 November, he finally obtained an audience. In attendance were not only Phaulkon, ‘that they could whisper together,’ but also Samuel White and Burnaby and, dressed ‘only in his drawers & shirt,’ the captain of Strangh’s own ship, Roger Paxton. What his purpose was, Strangh could not imagine, ‘except it was to bee a witnesse against mee for Phaulckon in what passed.’ Strangh ended the interview by denouncing Phaulkon as ‘the secret & hidden obstructer’ of the Company’s trade. He accused him of placing an embargo on sales of copper without the king’s knowledge, and then declared he would shut down operations. The embarrassed phrakhlang begged Phaulkon to take charge. He did so by claiming that Strangh ‘had runne [him]selfe into a great primonarie (praemunire), to contradict the King’s order.’ What, he asked, did he imagine would happen if he chose to enforce the rigour of the law? It were best, indeed, that Strangh should leave.

Still, it took a month for him to receive his exit pass. When, eventually, he departed, he wrote a vituperative letter to Phaulkon, declaring that,

You by the abused authority of your great Master & favour of our nacion, not acquainted with your prancks & tricks, has not only privately but publickly, some on paine & forfiture of life and goods others with threatning of imprisonment, forbidd & hindered all merchants, broakers &ca soe much as peepe or come near the factory either to buy or sell with us, as is evident to bee proved with your scurrilous reflexions on the Honourable Company of being broak & not worth a cowree …

For this, Strangh was criticised by Surat’s Sir John Child. In May 1685, he sent the Falcon to resuscitate the factory. He wrote that the Company,

… have suffered by the folly of some of their servants that have been there, cheifly from peevishness &c giving dislike to Mr Constant Faulcon, thinking meane of him because he came out in one of the Company’s ships in a meane imployment.

Phaulkon, he believed, should be treated with ‘hansomeness’, on the grounds that he ‘must have more love for us then for the Dutch or French.’ Others disagreed. In February 1684, Peter Crouch, of the Delight, was imprisoned for three days for refusing to supply Phaulkon with some nails. He accused Phaulkon of using his associates to clothe his worst qualities before ‘slipping off your English coate & appeareing the right treacherous Greeke & follower of Judas.’ Samuel Baron called Phaulkon ‘the most mailitious enviterate arch-enemy to their Honours’ interest, forgetting he was raised by White’s craft, Burnaby’s folly and with the Company’s stock.’ He recommended sending a military expedition.

On 17 June, the Directors announced that,

Constant Phaulcon … hath so intollerably abused the Company’s servants there & invaded all the English privileges … that we can noe longer endure his oppression nor adventure again with any ship into his ports until that ill man be punished by the King of Siam according to his desert.[44]

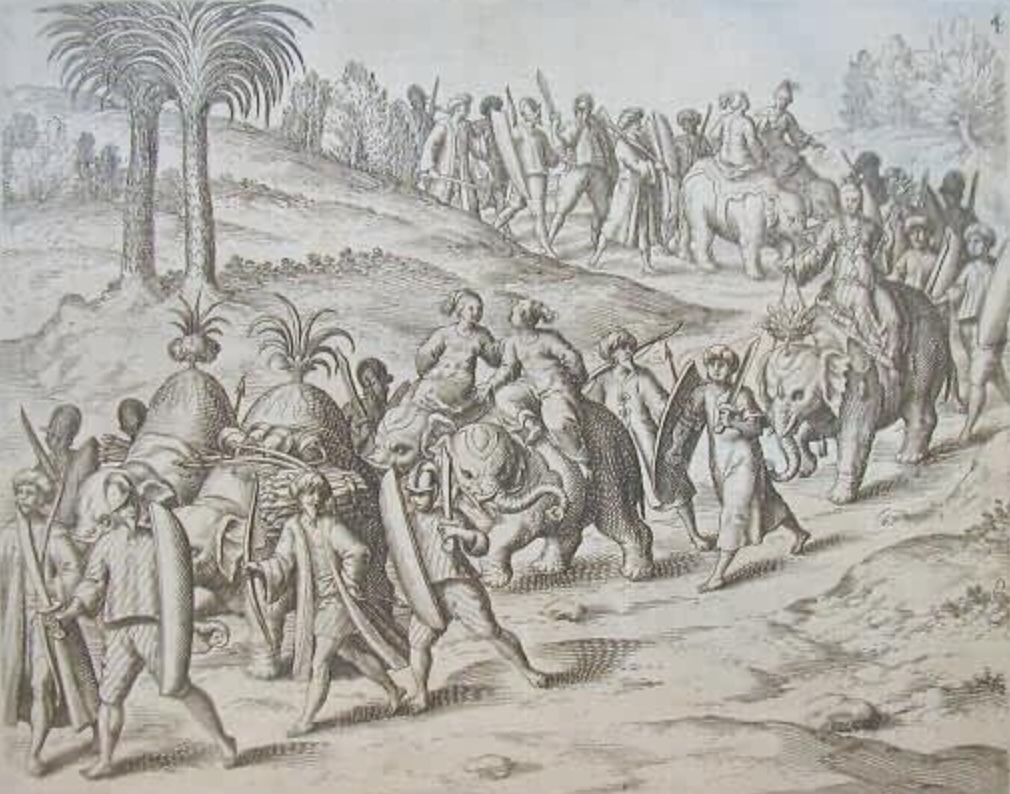

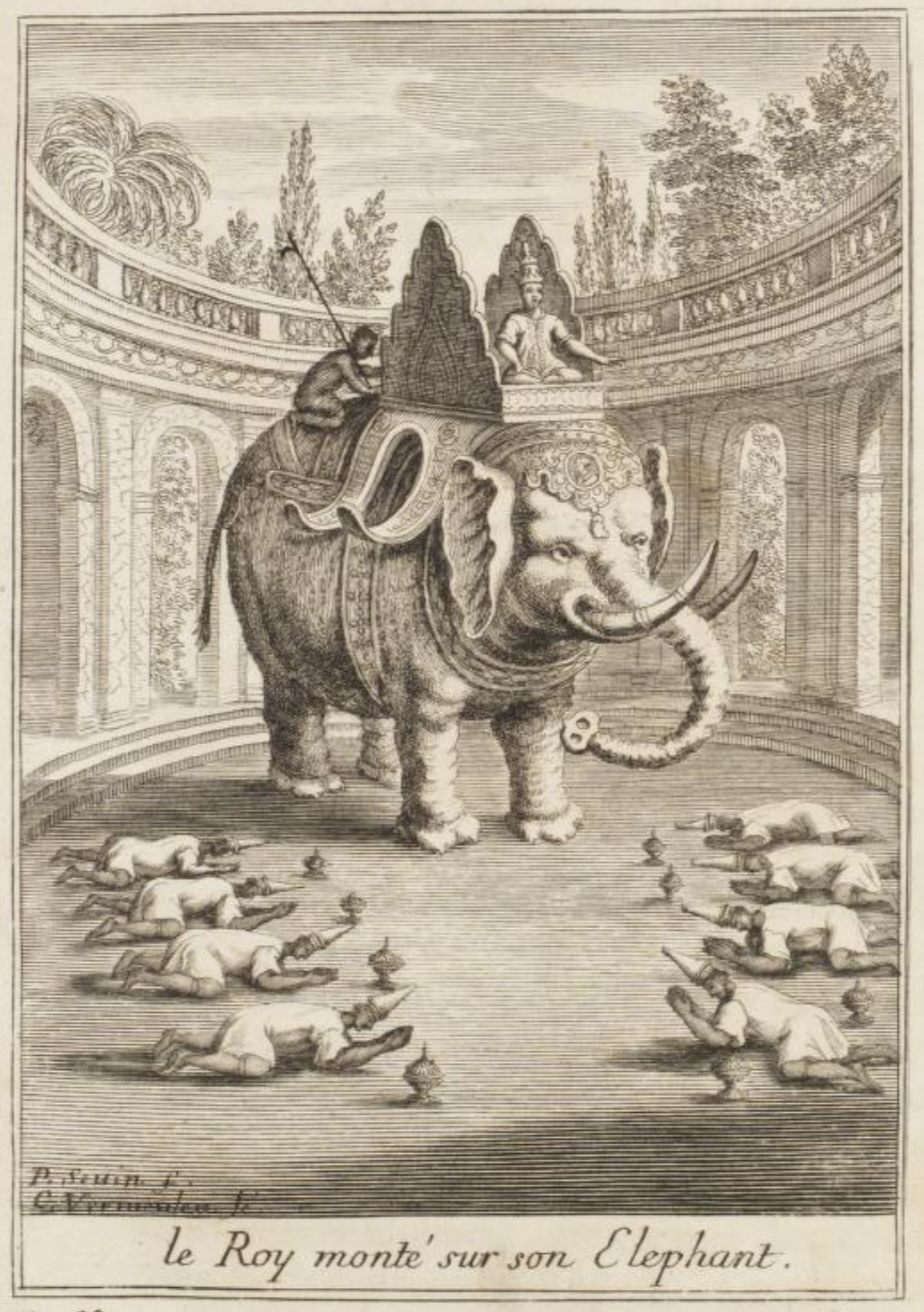

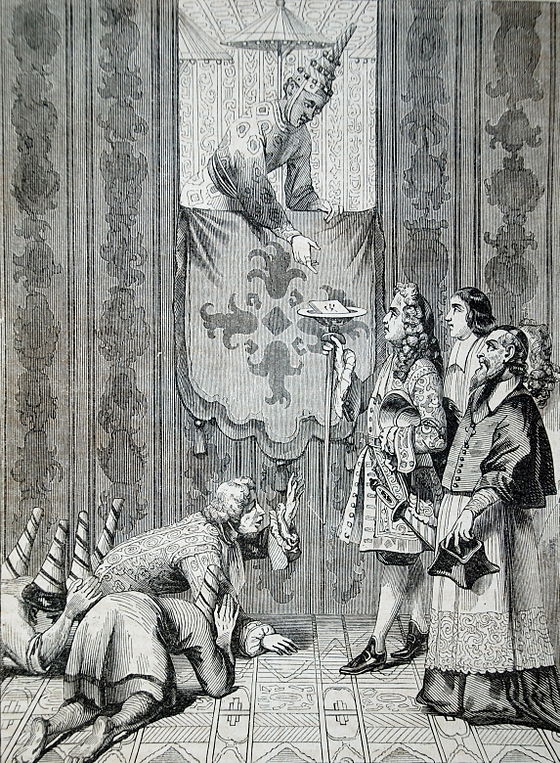

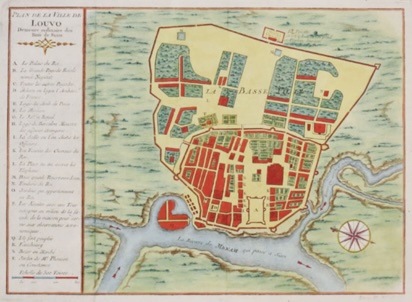

Samuel White Takes Centre Stage

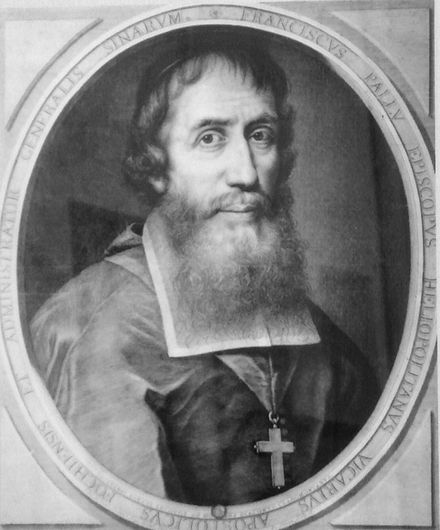

To protect his position, Phaulkon now advocated turning to France, whose vicars-apostolic had established a seminary in Ayudhya, in 1665, and whose Compagnie Royale des Indes Orientales had followed, in 1680. From the time at which he received three bishops at Ayudhya, in October 1673, King Narai had been minded to cultivate the French as a counterpoise to the Dutch. At Lopburi, in November, he even offered a port within his realm, ‘where they might build a town in Louis the Great’s name, which might later become … the residence of one of his viceroys.’ Embassies sailed to Versailles, in 1680 and 1684. Phaulkon, then, was pushing at an open door. In 1683, the phrakhlang was dismissed for corruption, and Phaulkon became the effective head of foreign trade. Burnaby was appointed governor of Mergen, and Samuel shahbandar, responsible for maritime affairs. [45]

One of White’s first acts was to rescue the Golden Fleece, a Company vessel which sprang a leak at Mergen whilst returning from Bengal to England. She was excused the charges of the port and her cargo was replenished at the king’s rate. (White claimed this saved the Company £190,000).[46]

He next considered how he might wrest maritime trade from the merchants of Golconda and inflict revenge on Ali Beague, for his earlier near drowning. He sought sanction to seize Golcondan ships and force open the market. Phaulkon agreed, but cautioned that, as the French were not yet able to provide protection, care should be taken to spare the Company. Samuel despatched John Coates across the Bay. Then he was informed that his authorisation had been revoked. Showing his true colours, he sent a second ship, the Dorothy (Captain Cropley), with two sets of instructions – the new, official ones and a plan for a casus belli. At Madapollam, Coates was to place an order for the repair of his vessel, the Prosperous, and for two new ships. When these were nearly ready, he would pick a quarrel, claiming they were being unlawfully withheld. Then he would take his prizes.

The policy was pregnant with risk, but Coates started well. He was generously entertained at Fort St. George, and recruited Alexander Leslie, Joseph de Heredia, and others to Siamese service. Then he got into trouble. ‘Blown with ambition’ and having ‘by his careless lavishness’ burned through his money, he captured not just a Golcondan ship, the Redclove, but the New Jerusalem, which belonged to John Demarcora, an Armenian under Company protection. (She carried two chests filled with cash and rubies.) Next, he blockaded Madapollam, capturing several boats, some of which belonged to Robert Freeman, president at Masulipatam. They would be returned only when his ships were delivered up. Not unreasonably, the Golcondans considered the Company the abettors of Coates’ actions. They demanded the arming of two vessels to blockade him in the river and threatened a fourfold penalty on the merchants’ losses if they were not restored.

Madapollam’s chief factor, Samuel Wales, absented himself, hoping to escape suspicions of involvement. His deputies, among them his wife, remonstrated with Coates, but ‘he made a laugh at all.’ If he surrendered the ships, he declared, he would be accused of accepting bribes, ‘and soe shall loose his life.’ Wales returned. He pointed out that, by failing to issue a protest before acting, Coates had opened himself to the charge of piracy. For fear of association, the Company would not involve themselves. Coates then learned that the governor of Ellore had sent a force to seize him. He sailed downriver and ‘slung severall shots into Narsapore.’ (Earlier, five or six of these had killed one woman, a son of John Demarcora, and ‘maimed som others.’) This time, ‘blessed be God, no harme was done.’

Eventually, Coates was persuaded that all of the Company’s business in Golconda was threatened. He was presented with a bill for damages, of £500,000, and another, of £45,000, in the name of the VOC. He returned most of Demarcora’s goods (but not the rubies). Masulipatam’s council expressed relief, but Coates was not done. A party of cut-throats was sent ashore. The Prosperous was set ablaze in her dock. An attempt was made to seize the governor. Again, Wales intervened. Afloat, he argued, Coates might escape the consequences of his actions, but those on shore had no such chance. Coates backed down. He returned the Redclove, and sailed away with the Jerusalem and goods, including the rubies, worth £6,800.

Compared to what might have been, the reward was small. White berated Coates for his pusillanimity: he would have to explain himself to the king. In high dudgeon, Coates pointed out that, at White’s instigation, he had disobeyed the king’s express command. What of White’s promise to ‘screen him from His Majestie’s displeasure?’ He pretended to take a fatal dose of opium and won the argument. Then, using some feigned antidotes, he effected a cure. That evening, they feasted together.[47]

Despite what had happened, Samuel maintained his course. When Cropley returned, he sent him to seize an Indian ship sheltering in Mergen’s approaches. Her cargo unloaded, she was armed, renamed Revenge, and placed under the command of Edward English. With Cropley, English sailed to Pegu, where he seized the Tiaga Raja, a vessel belonging to another merchant under Madras’s protection. Her traders were robbed and imprisoned in the godown. There they spent ‘eight dayes without eating or drinking … until they could no longer endure out of pure hunger.’ They were released once they signed a paper stipulating that White had done nothing untoward. By March 1686, seven ships had been seized. ‘Several others paid sawce for their being cleared.’ They included Robert Freeman’s Henrietta Maria. She was released ‘for Reasons no less publick than politick.’[48]

In March, Alexander Leslie captured the Quedabux off Point Negrais. On board was an American, Francis Davenport, who had travelled to India with George White and Phaulkon in 1670. Shipwrecked once and sold into slavery, he had been shipwrecked again and saved ‘at his vast charge’ by Joseph Demarcora, the Quedabux’s owner, and brother of John. Samuel hired Davenport to bring his accounts into shape. He was to use and abuse his services for the rest of his career. Davenport responded with split loyalties, then treachery.[49]

The depredations continued. The Sancta Cruz, another ship belonging Joseph Demarcora, was seized. She was sent to Achin with a prize crew, her owner and his son being held against her safe return. Out of personal obligation to Demarcora, who travelled to Ayudhya to plea for restitution, Davenport informed Phaulkon that the ship had been ‘taken under pretence of His Majesties Authority.’ Whether, by this, he intended to halt Samuel’s activities is to be doubted. Rescued from destitution, he was now being paid fifteen taels a month, only a little less than Elihu Yale, second in council at Madras. Nor did his conscience prevent him from doctoring the books.[50]

There was a need for some expertise in that regard because, in May 1686, White was summoned to the court at Lopburi (‘Lavo’) to give an account of himself:

… now all preparation is made for our Journey, the Souldiers and Seamen all paid off, and … because Mr. White would not appear to be in the Kings Debt, he invented a Muster Role of so many mens names (who for ought any man knows were never in rerum Natura) as swept out of the Kings stock 135 Cattees … and because it might be as troublesome to him to have any of the Kings Stores, as well as Cash in his hands, he resolves to make a Ballance of the Clongs Account, by reparting all the remains … as already disbursed and distributed upon all the Kings Ships, and accordingly the Kings Godowns were clean swept, and the Shabanders fill’d.

White asked Davenport to prepare a list of charges, so that he could practice his answers, if challenged. There were many, the most serious being the contrary orders issued to Coates. Consideration of them left White ‘more then ordinarily dejected in his Spirits.’ He was not being straight even with Phaulkon. Before they reached Lopburi, White was taken ill, close to death. He instructed Davenport to prepare an inventory of his assets. The ledger comprised 1,574 catties of Silver, ‘besides his Plate, Jewels and Rubies left at Mergen to the amount of 322 Cattees’, and 400 catties held in partnership with Phaulkon. Davenport was ordered,

… to write out another Leidger by it, only leaving out all his Adventures and Stock abroad, except those wherein the Lord Phaulkon was concerned with him …and the other, which … should be left amongst his other Books for the Lord Phaulkons perusal, when he should make enquiry into his Estate.[51]

Phaulkon knew White was becoming a liability. To make a point, he kept him waiting for three days. When White complained, he was warned he might be his own worst enemy:

… be cautioned to be plain, fair, and moderate in your Answers, to whatever Queries [our Secretary] proposes to you; avoiding all Passionate Expressions or Gestures, which may do you much harm, and cannot avail any thing to your advantage.

It will be no small pleasure to us, to find you as innocent as you pretend, nor shall we ever take delight to ruine what our Hands have built up; but if we perceive a Structure of our own raising begin to totter, and threaten our owne ruine with its fall, none can tax us with imprudence, if we take it down in time.

At best, this was a mixed message. White feared he might not be permitted to return to Mergen; that the Comte de Forbin, the French commander at Bangkok, might be sent in his stead. In that event, White would lose his room for manoeuvre, his trade and, in extremis, his means of escape. Burnaby was put on alert. The wisest course might be to withdraw. If he did so, he was asked to realise White’s assets first, and to remit them to George in England.

Samuel’s worst fears were not realised, however. By filleting the evidence, Phaulkon got White off, though it was a close-run thing. Referring to the orders issued to Coates, he warned,

If I have frown’d on you, read [this] Paper, and ‘twill satisfie you that I had reason; and if that be not enough to convince you, I can produce several of your own Letters wherein you have, so far forgotten your self, as to abuse us with not a few flat Contradictions; and I make no doubt but that your Accounts, if thoroughly scann’d, would appear notoriously unhandsome; but not being desirous to Ruine you, I forbore exposing you or them to the strict Examination which the matter justly required.[52]

Phaulkon could not afford to let Samuel get further out of line. In September 1686, it became clear why. A group of Macassars, who had settled near Ayudhya, rose in revolt. A preliminary plot was uncovered in August:

The design was to have fired the City of Syam; and whilst all the Inhabitants were busied in quenching the Fire, to have made themselves Masters of the Pallace, whilst on the same night a select number were to possess themselves of the palace at Levo, and murder the king with the favourite stranger, (as they called the Lord Phaulkon) and all the Europeans, being lookt upon as his Creatures.

The objectives of the revolt are a little obscure, but Narai’s reception of the Catholic French had something to do with it. Some high-ranking Siamese, possibly including two of the king’s half-brothers, were implicated. De Forbin had a narrow escape when he attempted to disarm a deputation of rebels at Bangkok’s fort. A little later, one of his captains, shamed into action by the boldness of those confronting the garrison, ‘too rashly advanced against such desperate Fellows, and with six or seven Portugueses that follow’d him met their Deaths on the point of their Enemies Creases.’ Later, Phaulkon assembled a group of Europeans, attacked the rebel camp and, with the loss of many lives, put them to flight. John Coates, in his armour, was ‘nockt into the water and drownded.’ Henry Udall, the visiting captain of the Herbert, also paid a heavy price. His mangled remains were buried at the Dutch factory. Their doctor found,

… on the left side of the hede the bones broak with great contusion of the utmost parts, the mussells of the neck wounded about the right eare, the fleshey part at the back side of the right upper arme cutt off, the left os humeri above the abovemost epiphisy broak by two bullets, the brest pearced in between the third and fourth rib on the right side and issuing on the left side between the 2 & 3 ribb …

Writing to his brother in England, Samuel commented,

You will not, (tho’ many others I believe will) wonder the Europeans small shot could prevent their doing so much mischief with only Lances and Creases, when you call to mind their desperateness, who are a sort of People that only value their Lives by the mischief they can do at their Deaths; and regard no more to run up to the very Muzzle of a Blunderbuss, then an Englishman would to hold his hand against a Boys Pop-Gun.[53]

Samuel now knew that Phaulkon was exposed to forces more powerful than his own. Later, he wrote that he was encouraged to remain at Ayudhya, and that Phaulkon offered to make him his successor, ‘in case of his Mortality’:

… but I have with much ado evaded it; for ‘tis true, I know he wants some body near him, that might be capable of assisting him with advice … yet I shall look upon my Head to stand a great deal faster on my Shoulders than his, so long as there’s ere a Ship or Vessel belonging to Mergen.

Phaulkon stood ‘in a slippery place’ and, if he slipped, his associates would lose their footing. White decided to return to Mergen as quickly as possible, there to

… make Hay whilst the Sun shines, and draw all my Stock, which now lyes scattered abroad, into as narrow a compass as possibly I can, and so to be in a readiness for any Revolution that may happen.[54]

Beforehand, he sought to obtain retrospective sanction for the orders he had so far issued. This would have protected him against the charge of piracy. It was refused. Yet, at the cost of some ruby rings, some sapphires and two Persian horses, White did receive expanded powers. Henceforth, the Tenasserim Council, of which he was theoretically the junior member, were

… obliged to affix the Seals of their Respective Offices to all Dispatches, Orders or Instructions whatsoever, which he [White] should for the future have occasion to Issue out, to any Commanders of His Majesties Ships, whether on Account of War or Merchandize.

In other words, if in future anything went wrong, White could blame the Council. He secured three hundred catties of state funding to go towards the next season’s adventures (or into his pocket), sent £12,000 to his brother, via Madras, and departed Ayudhya for the last time.[55]

At Mergen, he sold the stores he had earlier appropriated back to the fleet, at a profit of 280 catties. Its seamen were owed arrears in pay, so further funds were siphoned off using the fictitious names created earlier. Captain Cropley took the Dorothy and the Robin to Pegu, to seize upon vessels ‘that they might be examined and clear’d or condemn’d, as should appear reasonable.’ Alexander Leslie sailed in a powerful, newly commissioned ship, the Resolution, to Coromandel, to capture any vessels he met with, excepting only those that were European. Those he could not bring to Mergen were to be stripped of their goods and men and destroyed. Edward English took the Revenge to the north of Madras for a similar purpose.[56]

Meanwhile, White dispersed his fortune. The Delight was sent to Madras with between £3,000 and £4,000 in gold. She was followed by John Demarcora’s New Jerusalem, under French colours, for protection against Company patrols. The Derrea Dowlet sailed for Achin with a cargo of rice.

As he was lading the Satisfaction, White was ordered to deliver a quantity of the king’s tin to John Threader, whose ship, Agent, was being refitted prior to departure. White offered to store the tin on the Satisfaction until the Agent had been fully caulked and sheathed. He then arranged for her to be bilged, as she lay upon the mud, ‘by raving open three Butt-heads of her Plank.’ The following morning, as Threader argued with his captain over how his ship had come to be full of water, White, with an air of innocence,

… ask’t why they would offer to lay an old worm-eaten, weak, rotten Ship ashoar, that could not bear her own weight, with so much ballast in her.

The Agent was declared irrecoverably lost and the Satisfaction took the tin to Mocha.[57]

The Massacre at Mergen (1687)

It should not be wondered that, by now, Samuel’s credit with Madras was wearing thin. A particular antagonist was Elihu Yale, brother of Thomas, and president of its Council. He had been outraged by the suggestion that, in privately responding to a request to supply King Narai with some jewellery, he had sent rubies that were smaller than stated. In March 1686, Phaulkon had sent Thomas to Madras to obtain a refund. Angrily, Yale objected that he had received less in the transaction than he had incurred in costs, and that Phaulkon’s assayer had been terrified into giving a low appraisal. That much was clear, Yale stated, from ‘his expeditious survey of at least 1500 stones, sett very deep in fine gold, all which was dispatched in about two howers’.[58]

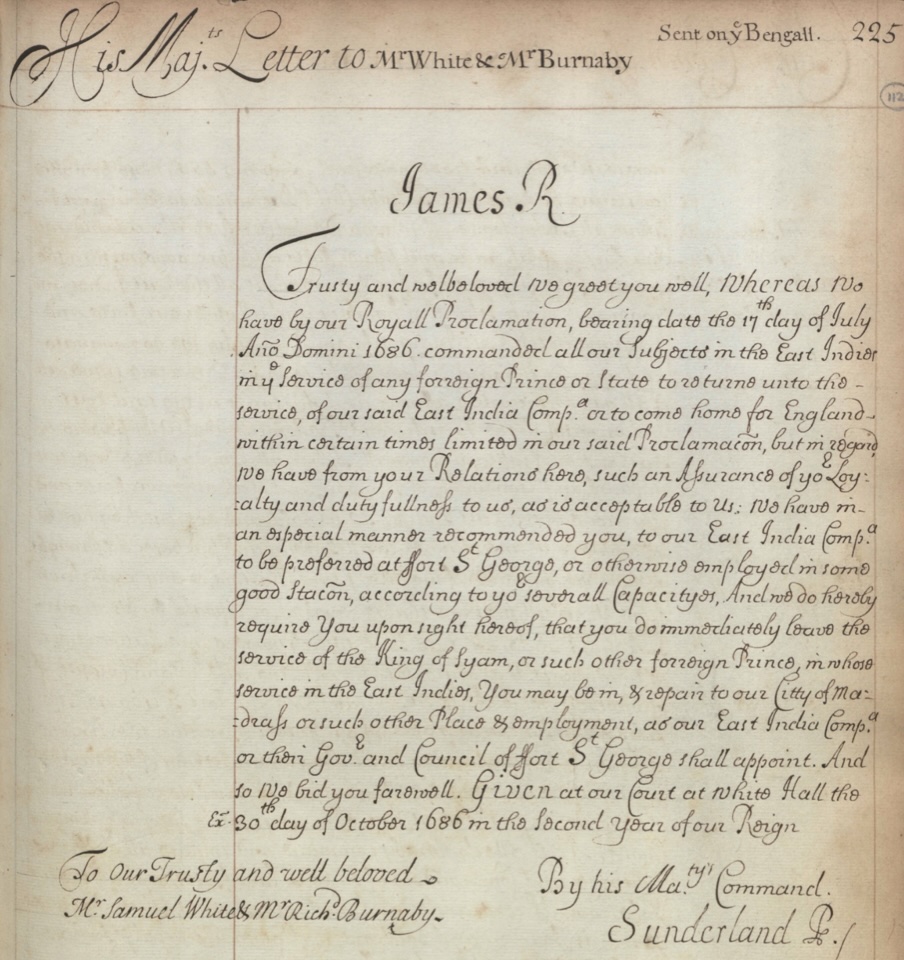

As Samuel later pointed out, there was much that was personal in Yale’s animosity. The bigger picture, however, was that London had long been demanding satisfaction for White’s villainy. In June 1686, Madras’s failure to get the message earned it the rebuke that there had been too many ‘mutuall kindnesses between you and Phaulcon.’ When they heard of Coates’ raid, the Directors were unsurprised by the blame attached to Fort St George. The truth, they opined, ‘is you have nourished those vipers.’ ‘The blame will yet ly heavier upon you,’ they warned, ‘if … you do not retrieve the damage you have thereby done this nation, by pursueing and executing those rebells.’ In July, King James issued a proclamation recalling his subjects from service with Asian rulers.[59]

In October 1686, White was warned of a British plan for occupying the island of Negrais, in the Irrawaddy estuary. He beat Fort St. George to it. Cropley sailed with his two sloops and claimed it for Siam. Later, he was told to withdraw. Phaulkon complained that White required authorisation before exposing ‘so many of the Kings Majesties Subjects to the rage of the English, if they should come there with a desire to fortifie.’[60]

In truth, Phaulkon had become nervous. He recommended that no merchantmen should put to sea and that the king’s goods should be put out of reach in Tenasserim’s klongs (canals). His suggestions were ignored. White believed the English were not yet ready to attack. In any event, there was virtue in having the goods to hand, if escape became necessary. Davenport begged to be gone but, by one means or another, he was persuaded to stay. Cropley lost his nerve. In February 1687, in breach of his orders, he appeared in the Dorothy, complaining that his instructions put him ‘at hazard of his neck.’ But for his family in Mergen, he declared, he would have surrendered his ship at Madras. ‘Those proceedings of Mr. White could never end well,’ he whined.[61]

In April, the Revenge was captured by the Company’s Captain Nicholson. This was a surprise. At Madras, the previous autumn, Edward English had been ‘kindly received and supplied with ammunition and men for the King’s service.’ Now, reports suggested that Madras had responded to the treatment of the Tiaga Raja’s merchants with anger. It was no bad thing to have the Dorothy to hand, after all. White’s greatest anxiety was his lack of written approval for the orders previously issued to Coates. Something had to be done, to protect him from prosecution for piracy. His solution was to persuade two members of the Tenasserim Council to affix their seals to a backdated commission, written in English, demonstrating that he had always acted on their authority. (They were told it referred simply to the despatch of a vessel.) Next, a scrivener was told to fill in the blanks with a Siamese translation of the true purport of the words. When the clerk protested, White told him the document was being sent to Europe, and nobody in Siam would see it. Davenport appended his authenticating signature.

Thus protected, White claims that he now alerted Phaulkon to the Company’s hardening attitude. He offered to be sent,

… as some fitting Person to the King of England, to give him a true account of [the malicious misreports of some], and endeavour to renew and corroborate that Correspondence, which His Majesty of Syam had in so many instances manifested his intention, and desire to conserve with the English Nation.

He says that the policy was approved, and that it was only because of ‘the sudden fatal change of things’ at Mergen that he was forced to flee.[62]

Davenport makes no mention of this effort at diplomacy. His advice, he says, was that White should go to Madras, claim he had acted under orders and, relying on the support of the interlopers, brazen it out with Yale. The idea was rejected with passion. White ‘would choose to be damned rather than go thither to be laughed at by Yale and Freeman’:

If ever a ship of the King of England comes to this Port, before I am gone [he declared], the Commander shall find me as civil to him, as he can be to me, but if once he comes to tell me that I must go with him, and pretends the Kings authority here, by the living God, I’ll pistol him with my own hands, and afterwards wipe my breech with his Commission.[63]

If he failed to get away, White swore he’d defend Mergen to the last gasp:

… they shall find Mergen the hottest place, that ever they came against in their lives, as simply as ‘tis fortified, for I am resolved never to go to Madrass, if there come Ten Sail of Men of War to fetch me, and if it does come to that pass … I’le defend the place as long as ‘tis possible, with the Natives, and when I can hold it no longer, I’le burn it down, and go to Syam by the Light on’t, and see who will fetch me thence.[64]

Burnaby was hung out to dry. For some time, White had despised his ranking superior:

[He was] fit to converse with no body but his Crim. Catwall, and take delight in being the Town Pimp, and disposing of all the Whores to any body that wants one, or keeps company with a parcel of Sailors, that over a Bowl of Punch, will lye worshipping him up, till he thinks himself a Petty Prince among them …

Burnaby could not be trusted with White’s secret preparations: they would be published through the town ‘with a gong’. He would have to shift for himself. If he was lucky, he and his few possessions – a few dozen plates and spoons, a few cloths and perhaps fifty catties in cash – could be put aboard ship at the last minute. Davenport had more time than this for Burnaby. He resolved to betray his master, but to wait upon events.[65]

Now the Dorothy (renamed Mergen) was prepared for departure, but the suspicions of the natives were aroused by the approaching monsoon. It told against a trading voyage. One gossiped that White intended to bolt. To stop his mouth, he was arrested, whipped, clapped in irons, and led through the bazaar to the gaol. Then, in a stroke of fortune, on 23 April, Leslie brought the Resolution into harbour. A passage via the Cape now offered itself instead of an enforced flight via the Gulf and Persia.[66]

The Resolution was laden with eighteen months’ worth of supplies. Then the Curtana and the James, Anthony Weltden commanding, appeared. His orders were to bring Samuel to Madras, to oblige all English subjects to leave Siam’s service, and to serve a bill for £65,000 in damages on Phaulkon. Staying out of the range of Mergen’s guns, he was to institute a thirty-day blockade. If, after that, satisfaction was not obtained, he was to take prizes. White and Burnaby were to be offered employment if they surrendered themselves and the port to the Company, rather than to the French or Dutch: Madras had no wish to be deprived of the trade or the convenience of repairing and fitting their ships there. If they refused, they were to be declared rebels. Weltden was to take possession, although he was warned ‘to bee very considerate in this affair, remembering the great supplies of French, lately arrived att Siam.’

Following two months behind him were James Perriman and William Hodges on the Pearl. Their complement of just nineteen men raised the force to sixty. (Pressures in Bengal meant Madras had no one more to spare.) They may have taken comfort from London’s idea that ‘there is no power at Mergee to resist one ship’s company & that the people there are a sheepish cowardly people … which will not fight.’ If they were so persuaded, however, they were in for a surprise.[67]

On 23 June, White greeted the Curtana’s deputation. Over dinner, he quipped that for him to go to Fort St. George ‘was just like a Mans making a good Voyage, and on his return homewards to fall into the hands of Andemaoners.’ He warned that his commission required him to defend Mergen, if attacked. Nonetheless, on 26 June, his associates signed a document certifying their acceptance of King James’s instructions. White and Burnaby ‘made scruple of it, but at last consented that Mr John Turner should do it for them.’ Thereafter, White did his best to exert his charm, but Davenport was an obstruction, whispering warnings in Weltden’s ear. On 27 June, as he prepared to cross to the Curtana for an unauthorised conference, White seized him and threw him into Tenasserim’s jail. Weltden protested, but Davenport was left to stew in his chains until 4 July. By then, White believed he had worked some magic. On 5 July, he left for Tenasserim.

The next day, two of his men were caught loitering in the harbour, preparing to secrete away the gold expected aboard the Satisfaction and Dowlet. A stockade appeared athwart the river. Weltden decided to act. On 9 July, he cut out the Resolution. On 11 July, White returned and discovered what had happened. Cannon were positioned in the woods. Natives filled bottles with gunpowder. When Welten visited White, he found him so enraged that,

… he had pulled down the out-buildings that encompassed the square at his dwelling Hourse, and all the Banisters and Rails, which surrounded a brick Platform before his door …

The noise brought some Siamese officials running. Lieutenant Mason reported that White had cried out to them that the English had come to burn the town, and that he was denying them the satisfaction of burning his house. It was disconcerting intelligence, but, by degrees, Weltden calmed White down and, before long, he was declaring they were ‘stricter friends than ever.’ Davenport was suspicious. He had reason to be. When he asked Weltden why the James was being moved to a position nearer the fort and its cannon, he was told that, if she had remained where she was, ‘the Country people, being so hot exasperated at the bringing away of the Ship, might perhaps burn her.’ Now, Weltden said he was going ashore,

… to treat with the Shahbander about his taking several Goods off their Hands, and putting his Money, Plate, Jewels, and the most considerable part of his effects into their hands, for Transport, to and concealment of it at Madrass.

This reads like an attempt by White to strike a deal. Later, he promised to return the Dorothy to India laden with ‘Masts and Yards, Timbers and Plank … chiefly for Captain Weltden’s Account’ and to ‘take off the Captains hands all the Lead in the ship (Curtana), and give him Tin in the room of it.’ Meanwhile, he was stirring the Siamese to attack, his plan being to ‘rescue’ Weltden aboard the Resolution, and to accuse Ayudhya of issuing the orders. In this way, he hoped to secure his valuable cargo and Weltden as a witness to his honourable behaviour.

There was an awkward moment, at eleven o’clock that night, when Lieutenant Mason noticed that the river was becoming over-spread with war boats. He was bold enough to remark that something might be being meditated against the Curtana. White’s off the cuff response was that ‘in those Boats were no body but a parcel of poor harmless fellows come to sell a little Beetle nut.’ Mason, it seems, allowed his incredulity to get the better of him for, next,

… with a great many execrable Oaths and Curses [White] swore that since they apprehended danger where there was none, he would go along with the Captain aboard Ship, and be his Guard, which accordingly he did, running down stairs like one distracted, without Hat, Slippers, or any thing but his Night Gown, and a pair of Drawers; in this posture, raving, swearing, protesting and pawning his Soul, that ne’er a Finger of their Hands, or a Hair of the poorest mans Head in the Ship should suffer any harm.

In the end, Samuel got the result he intended, but not as he expected it. At 10 o’clock at night on 14 July, the men aboard the Curtana heard small arms’ fire, then the roar of cannon. A little later, they spied flames near the shahbander’s house and by the shipyard. There followed the sight of a vessel ablaze. Weltden continues,

… all men stood gazing on the action; some of them saying, they thought the Shabander to be in a frolick, and to have only ordered the Guns to be fired, and the old Bengal Ship to be burnt, in Civility and Complement to the Captain, who had treated him so nobly on board the other night; Until (about 12 a Clock) Captain Armiger Gostin came on board with his Mate, Mullins, and four others, who told them, that all the English were cut off on shore by the Natives, and that his Sloop (James) was beat to pieces by the great Guns from both Forts, and that themselves, had with much difficulty, escaped to bring them the News.[68]

White and Weltden were fortunate to escape with their lives. (Weltden was saved by a stout beaver hat, which ‘warded off a blow from being mortal.’) Sixty or more others – including Burnaby – were slaughtered. The rest escaped on the Resolution and the Curtana.

On 11 August, Phaulkon issued a declaration of war on the Company, in the king’s name. Aside from unpaid debts, Potts’ ‘debauchings’, Yale’s rubies, the action taken against Coates at Madapollam, and the seizure of the Resolution, he claimed that, on 14 July, Weltden’s men had

… commenct to play their gunns which they placed in the Controuler’s house, seated about 30 fathom distance, in order to be frighting the foresaid government of the province of Tenassare from their duty, whereby they might posess themselves of the place with great facility.

White had vowed never to surrender Mergen, but Madras had promised to forgive him if he did. Even if some of Phaulkon’s claims are fanciful, it was reasonable for his mandarins to have believed this was White’s plan.[69]

On 21 September, the Pearl arrived outside Mergen, where she was greeted by the Dorothy and the sloop Robin. There was talk of pirates and something about them was suspicious. According to Hodges,

The ship had 24 guns with an English ensigne with the cross downward and the white sullied with red … The commander Captain Cropley speaking to us, we commanded him on board, but he said we should come on board him. Whereupon we poured a broadside into him and seconded it with our small arms … The one shott cutt the tackle-block over his head, the other went through the sleeve of his gown. This we continued until night parted us.

The next day, as she entered harbour under a flag of truce, the Pearl was seized. Perriman and Hodges were informed that a Frenchman had come to take charge. Of the Curtana there was no trace. On 4 October, Hodges, whom Madras had minded for Mergen’s governor, was packed off to Ayudhya, complaining bitterly that the Pearl’s rotten ammunition and provisions had given him no option but to surrender. He was thrown into prison. In December, he wrote outlining the Siamese side of the story. Tenasserim’s governor had been ordered by the king to stop White and Burnaby from escaping. When Weltden took the Resolution out of the road, the governor consulted with some ‘rascally’ Dutchmen, who advised that the Englishmen should be killed. (Cropley may have been privy to the design.) The massacre was performed by ‘a parcel of people made drunk & madd,’ who acted on the principle that ‘the more they murder’d, the more would bee their profit.’ The king was deeply grieved at the way things had spiralled out of control. Cropley, a Dutchman, and several natives had been arrested. At Lopburi, the governor’s flesh was to be ‘pinched off with hot Irons.’ In the meantime, however, Madras should note that ‘there was att Mergen, five Companies of French, and Above 300 disciplin’d Siammers.’ In short, the Siamese government denied it was responsible for the massacre, and declared that Mergen was properly protected, should the English think of taking reprisals.[70]

White and Weltden withdrew to the archipelago. The Curtana needed careening, and Weltden took her to Negrais for the purpose. White did not follow, his priority being to wait for the Derrea Dowlet and the Satisfaction. Since these had been captured, they were missed. Even so, the Resolution reunited with the Curtana at Achin. White knew that flight at an early juncture would place him under suspicion for the massacre, but only Weltden believed he would deliver himself up. Either he was extraordinarily naïve, or he was persuaded that White’s faked commission absolved him of the piracy charge. Davenport tried to put Weltden straight. When he got the wrong response, he prepared a written ‘protest’, claiming that Weltden and White were co-conspirators. When he threatened to put it before Fort St. George,

[Weltden] swore bitterly he would clap the said Davenport in Irons before Sun-rising; that once he thought not to ask him a Farthing for his Passage … but now he should go ashore at Madrass in his bare Shirt, and should not carry with him a Rag of Cloaths, or Penny of Money, or his Boy, nor an Inch of Paper out of his Ship, until he had paid him sixty Pagodoes …

By now, the ships were anchored in Madapollam Road. The following passage shows that, in their alarm, Weltden and White tried to involve a brigand, John Noleman, in a quarrel with Davenport and so rid themselves of their denouncer:

The Yaule, on the 17th of December, at her second return from the shore, going … first on board the Resolution, brought John Noleman thence, who declared he was ordered, and came on board to quarrel with, and spit in the face of one Davenport; and did indeed rail against him sufficiently, having perfectly learnt his Lesson before he came, but not knowing the man he mist of his Errand; for the said Davenport stood many times by him unconcerned, and smiling at the fancy of those that employed him, for Noleman would take other men for him.