Towerson’s birth date is not known. The son of William Towerson, a Guinea trader, and Parnell Wilford, the daughter of well-connected merchant and MP, he was baptised at St. Michael’s, Cornhill, on 27 February 1576. William Towerson made three voyages to Equatorial Africa between 1555 and 1558. These embraced cargoes of gold, ivory and pepper, battles with Portuguese and French competitors, and disease. After the third voyage, in which one vessel was lost and another abandoned for lack of crew, William shifted his attention to Antwerp and Iberia. A freeman of the Skinners’ Company, he joined the Spanish, Muscovy and Eastland Companies, and became a councilman of London and an adviser to the Privy Council on merchant affairs.[1]

Gabriel had eleven siblings, one of whom (another William, some twelve years his senior) sailed in the Edward Bonaventure during Edward Fenton’s expedition of 1582-1583. This William was later a member of the Spanish, Eastland and Muscovy Companies, and served as Master of the Skinners Company, in 1616-1617. He was a director of the East India Company between 1619 and 1622.[2]

The First Voyage of the East India Company (1601-1602)

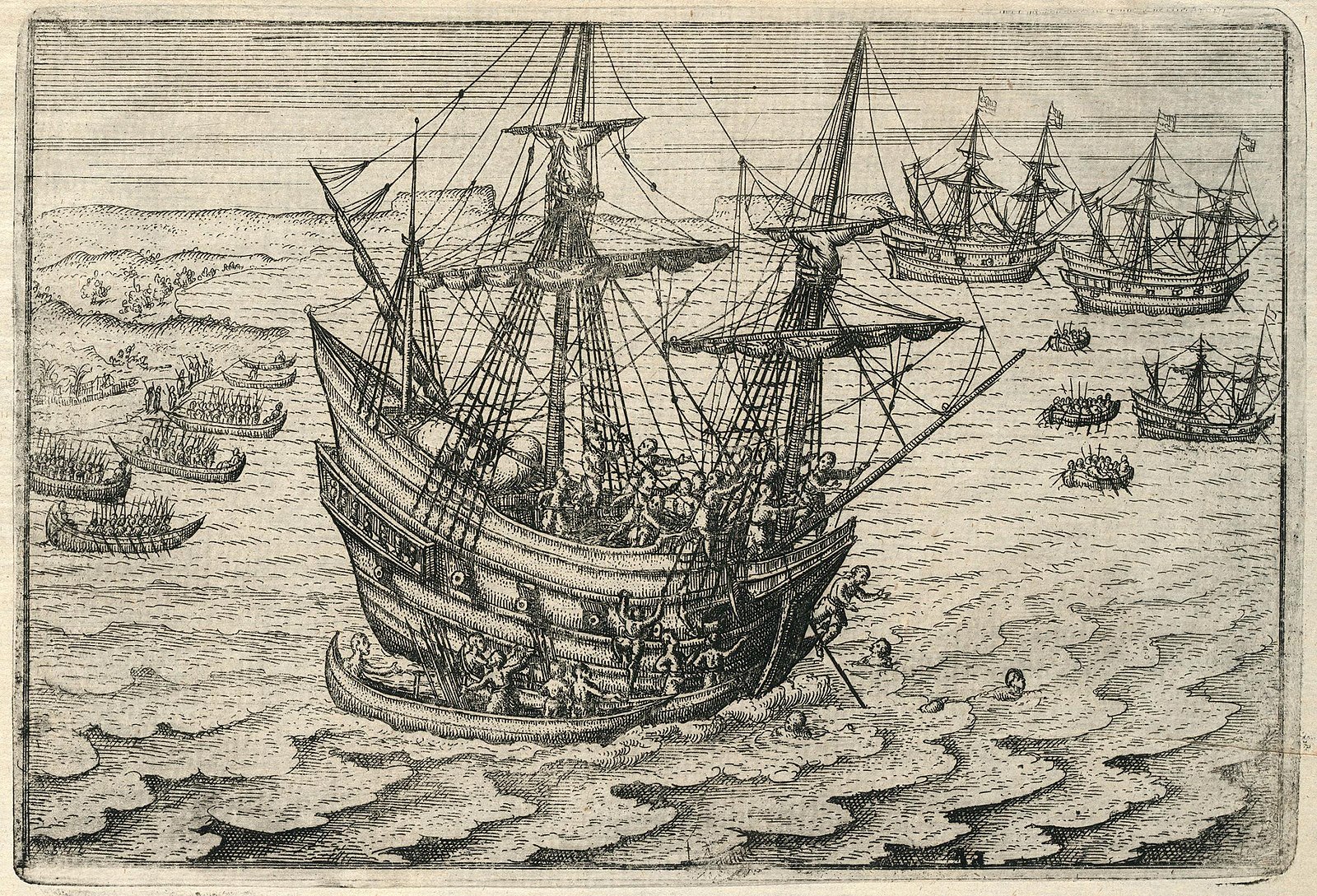

Gabriel was twenty-six or twenty-seven when he sailed on the Company’s First Voyage. It is not clear in what capacity he served, although it is likely that he held junior rank. There were four ships, of which the principal was the Duke of Cumberland’s Malice Scourge, renamed Red Dragon. She had a burthen of at least six hundred tons. The Hector, the Ascension and the Susan were veterans of the Levant trade, and less than half her size. James Lancaster was in overall command; John Davis, who had recently returned from a voyage to Asia with Cornelis de Houtman, was pilot-major.

Despite initial enthusiasm, collecting finance for the voyage proved troublesome. Several subscribers withdrew their commitments, until they were prevailed upon by the Privy Council, under the threat of punishment ‘as their obstinacye and pversenes shall deserve.’ Three were disenfranchised. One, suggestively, went by the name of Robert Towerson. Another was Sir Edward Michelborne, a friend of the Earl of Essex, who, in October 1600, had been proposed as commander by the Lord Treasurer. No doubt, Sir Edward was piqued by the Directors’ rejection of him. Claiming that the employment of ‘anie gent in any place of charge or comandement’ would be much ‘misliked’, they determined to ‘sort ther busines with men of ther owne quality.’ Events were to vindicate their judgement. Gabriel Towerson experienced Michelborne’s malign behaviour later.[3]

Assuming that the English were permitted a continuing trade at their destination, the Directors instructed Lancaster,

… that you shall select, out of the youngest sorte of our factours and others intertayned by us or voluntarilie suffered to goe in the voyadge, such and soe many of the aptest and towardest of them as you shall thinke meete, and as shall have best approved themselves fit for such an ymployment, to recide and abide in those places where you shalbe soe peaceablie received … takeinge sufficient and carefull order for the defrayinge and supplyinge of their chardges untill those places shall be hereafter visited with another fleete …[4]

Gabriel Towerson was one of those so chosen. He was resident at Bantam, on Java, from December 1602, until late 1608.

The earlier voyages of the Edward Bonaventure had made plain the need for a prompt departure. Unfortunately, although speedy preparations meant Lancaster’s fleet left Woolwich on 13 February 1601, contrary winds confined it to the Channel until 2 April. The passage through the Doldrums was slow and, by the time the winds revived south of the Equator, in early August, disease had taken hold:

… very many of our men were fallen sicke of the Scurvey in all our ships, and unlesse it were in the Generals ship only, the other three were so weake of men that they could hardly handle the sayles … For now the few whole men we had, beganne also to fall sicke, so that our weaknesse of men was so great, that in some of the ships, the Merchants tooke their turnes at the Helme: and went into the top to take in the top-sayles, as the common Mariners did.

Better conditions on the Dragon manifested Lancaster’s understanding of the value of antiscorbutics. For as long as stocks lasted, he required his men to take three spoonfuls of lemon juice every morning, and to keep to a minimum their consumption of salt meat. The result was that, although the Dragon’s crew of two hundred was at least twice that on the Hector, Ascension, or Susan, fewer sickened or died. Even so, the toll on the fleet was heavy. Of the 404 men who left England, 105 perished before reaching the Cape. Whether Towerson was fortunate enough to sail in the Dragon, we do not know. Were it so, he will have been required to help the other crews into Table Bay. They were ‘hardly able to let fall an Anchor, to save themselves withal.’[5]

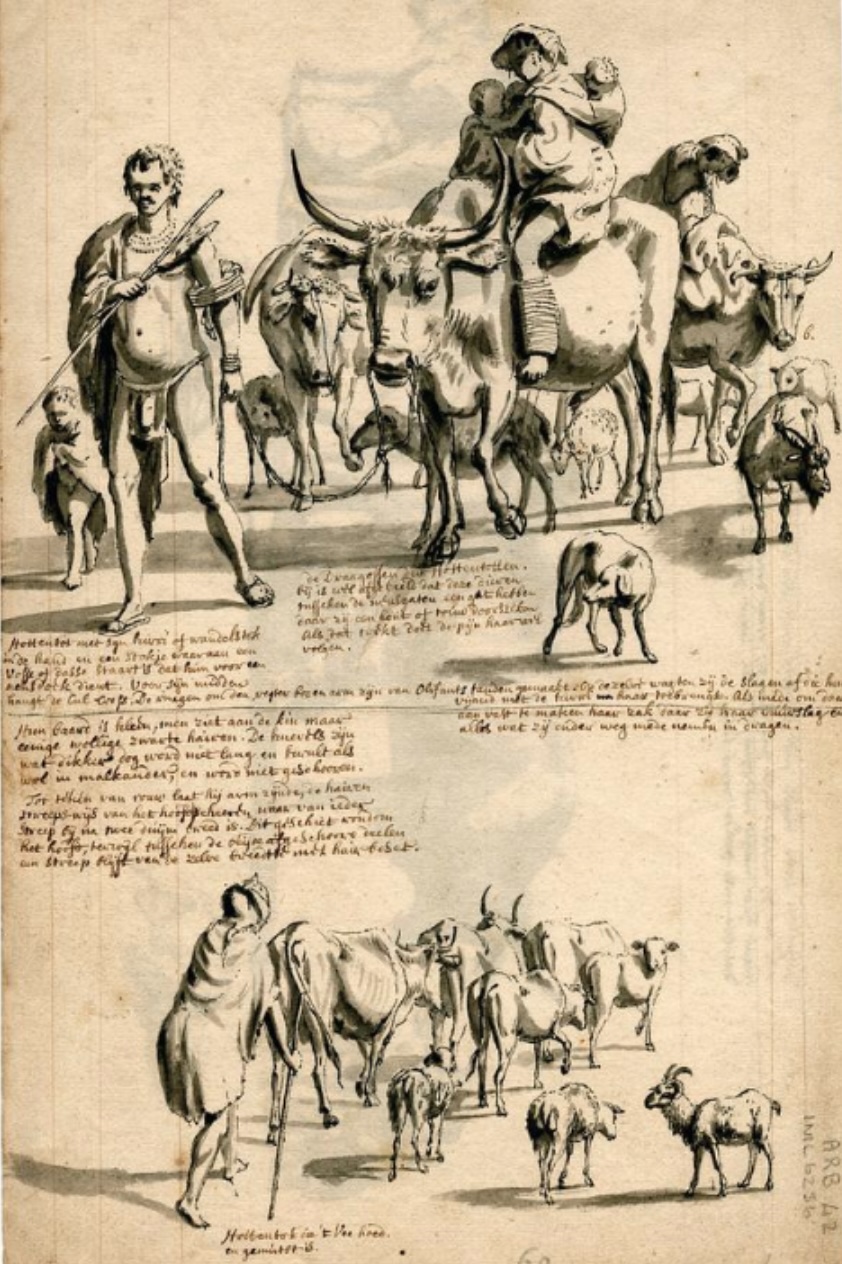

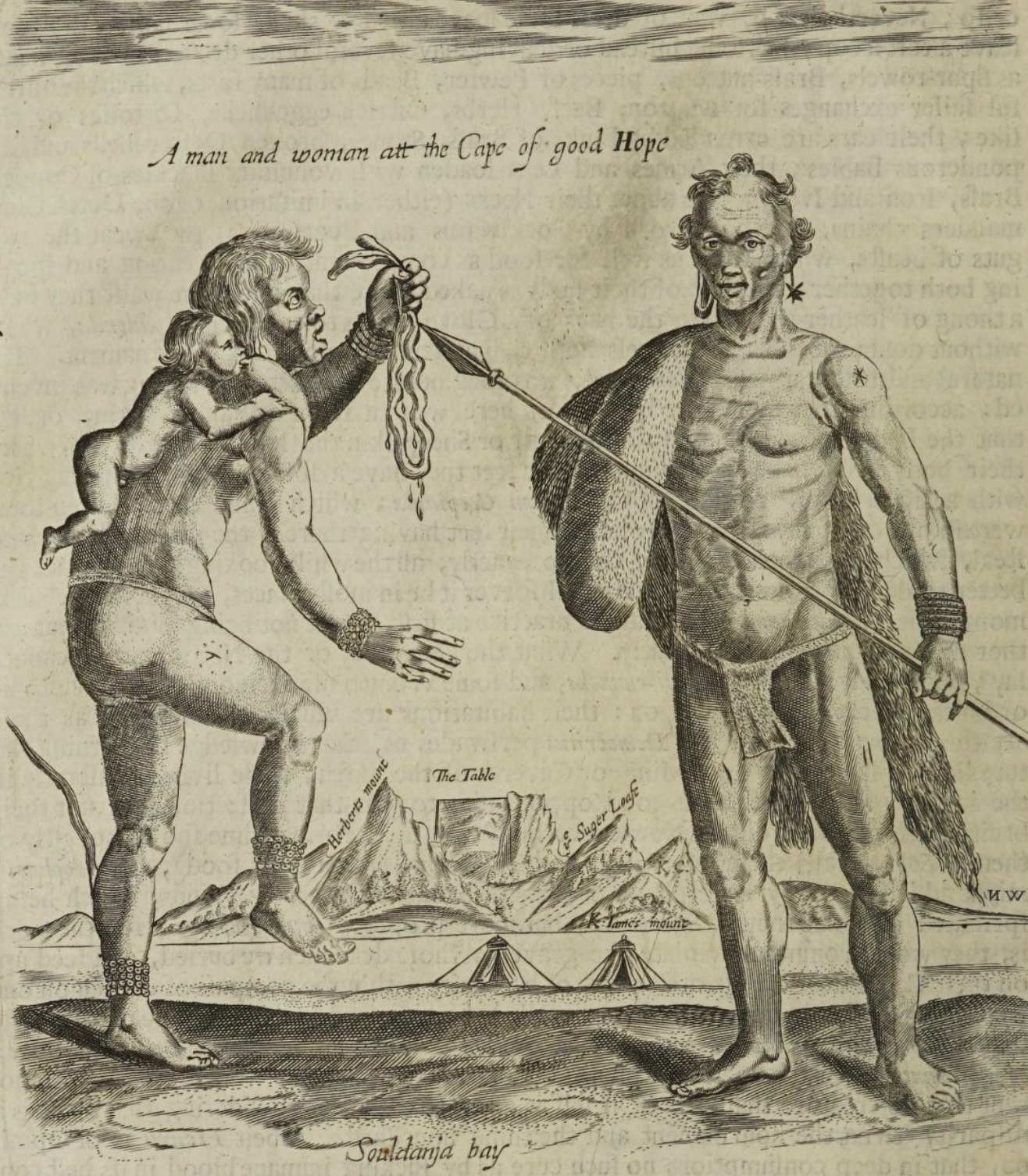

The Cape, however, was an excellent place at which to convalesce. In 1591, Lancaster had considered the Saldanians ‘very brutish’. In 1601, they were judged less so, though ‘much given to picke and steale.’ Their language, ‘wholly uttered through the throate’ was indecipherable, but Lancaster spoke to them ‘in the Cattels Language … which was Moath for Oxen, and Kine, and Baa for sheepe.’ This obviated the need for an interpreter. A ‘royall refreshing’ was obtained in exchange for trifles, such as knives and pieces of iron. By the end of October, all but four or five men had recovered. With ample provisions on board – including some birds ‘of the bignesse of a ducke,’ with ‘finny wings’ and ‘a strange and proude kinde of going’ – the fleet departed stronger than it had been on quitting Woolwich.[6]

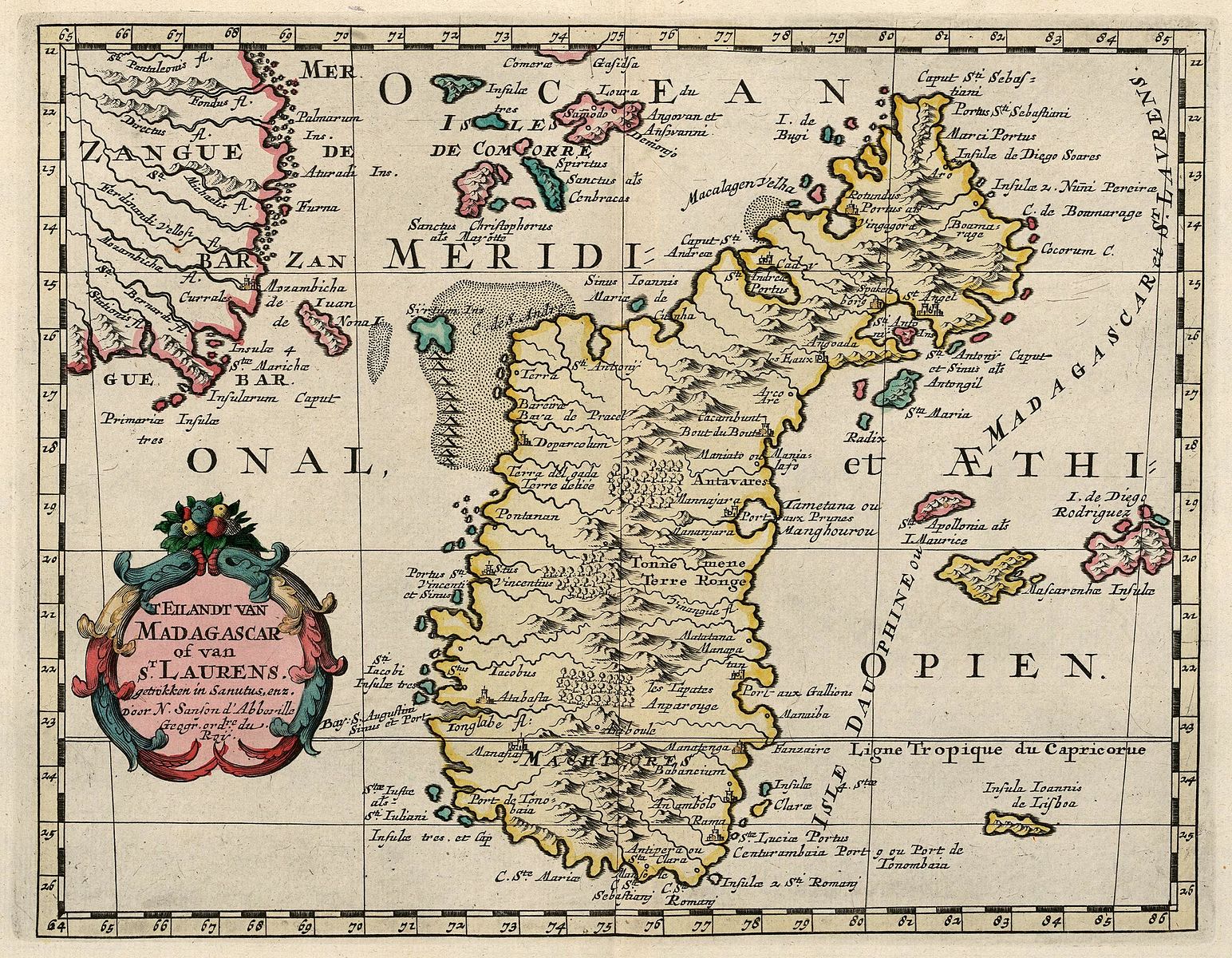

After the Cape, progress was delayed by contrary winds. Cases of scurvy reappeared. Lancaster stopped at Antongil Bay, in Madagascar, to replenish stocks of lemons and food. The natives here were ‘very subtill, and craftie, in their bartering,’ but supplies were obtained in exchange for beads. Unfortunately, floods made the water unwholesome, and a number succumbed to dysentery. Some of the Susan’s crew decamped ashore until, wearied by the scantiness of the fare and lodging, they returned aboard. They were punished for their offence. Christopher Newchurch, surgeon on the Ascension, took poison, although he failed in his purpose. But for the Susan’s captain, who accepted him as an ordinary seaman, he would have been abandoned. More unfortunate were the Ascension’s captain and boatswain’s mate. They went ashore to attend a burial and fell victim to the Dragon’s cannon. Before firing a salute, her gunner was ‘not so carefull as he should have beene.’ A ball struck the ship’s boat, and ‘slue’ them ‘starke dead.’ As the chronicler puts it, ‘they that went to see the buriall of another, were both buried there themselves.’[7]

On 6 March, the fleet sailed for the Nicobars, which, after an unexpected encounter with the reefs of the Chagos Islands, were obtained, on 9 May. The Portuguese used these islands as a stopping place en route to Malacca, and as a source of ambergris. As a result, the natives were fearful, and the refreshing was ‘daintily’ priced. Even so, Lancaster stayed ten days, sufficient to grant him sight of some ‘sacrificers’ on ‘Sombrero Island’ (Nancowry):

[They were] all apparelled, but close to their bodies, as if they had beene sewed in it: and upon their heads, a paire of hornes turning backward, with their faces painted greene, blacke, and yellow, and their hornes also painted with the same colour. And behind them, upon their buttocks, a taile hanging downe, very much like the manner, as in some painted cloathes we paint the Divell in our Countrey. He demaunding, wherefore they went in that attire, answer was made him, that in such forme the Divell appeared to them in their sacrifices: and therefore the Priests, his servants, were so apparelled.[8]

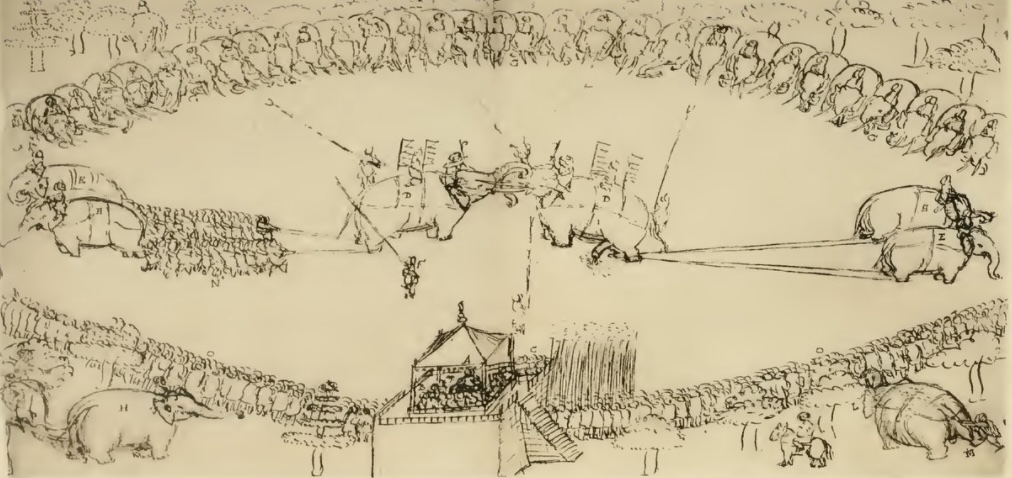

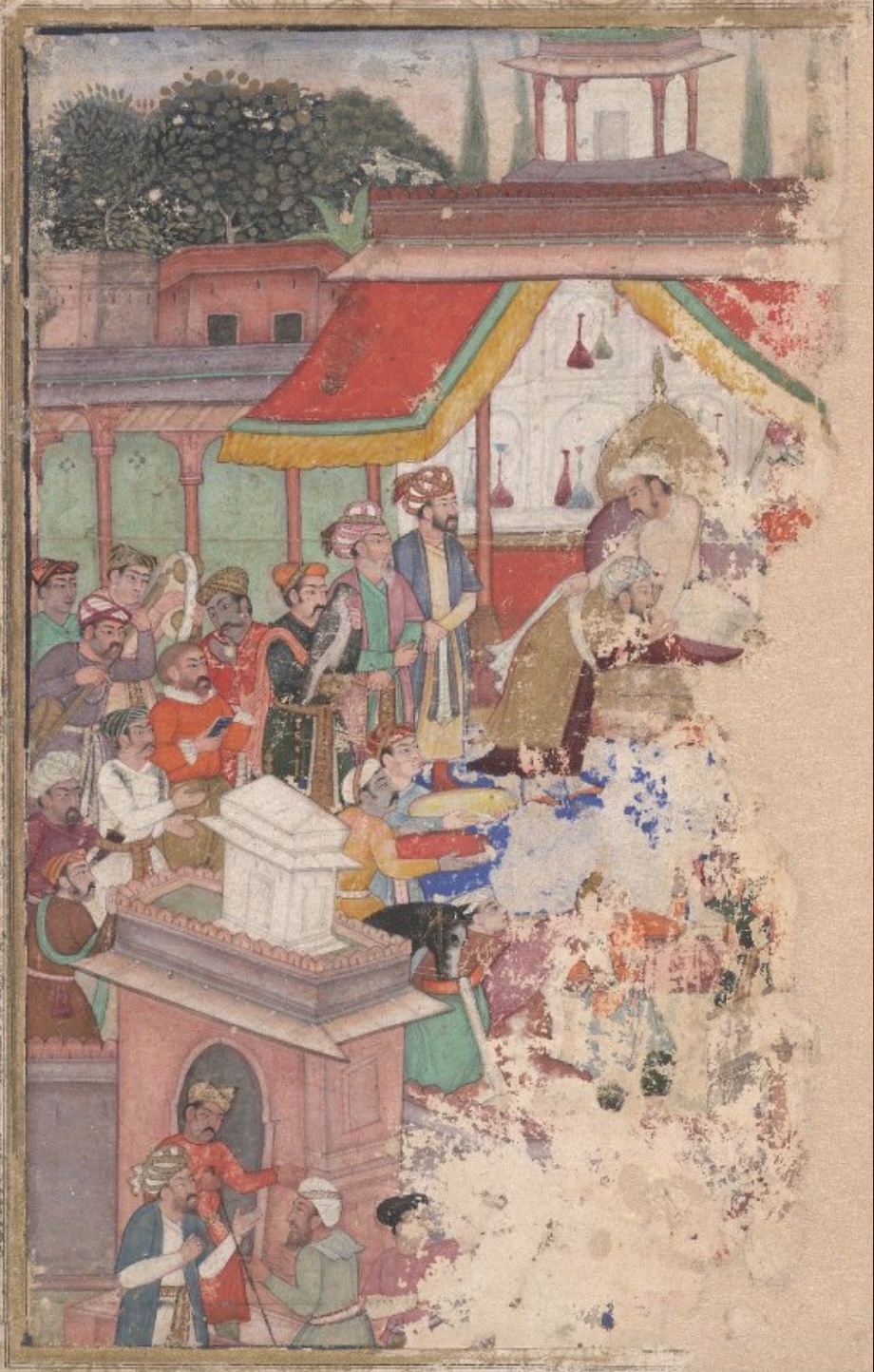

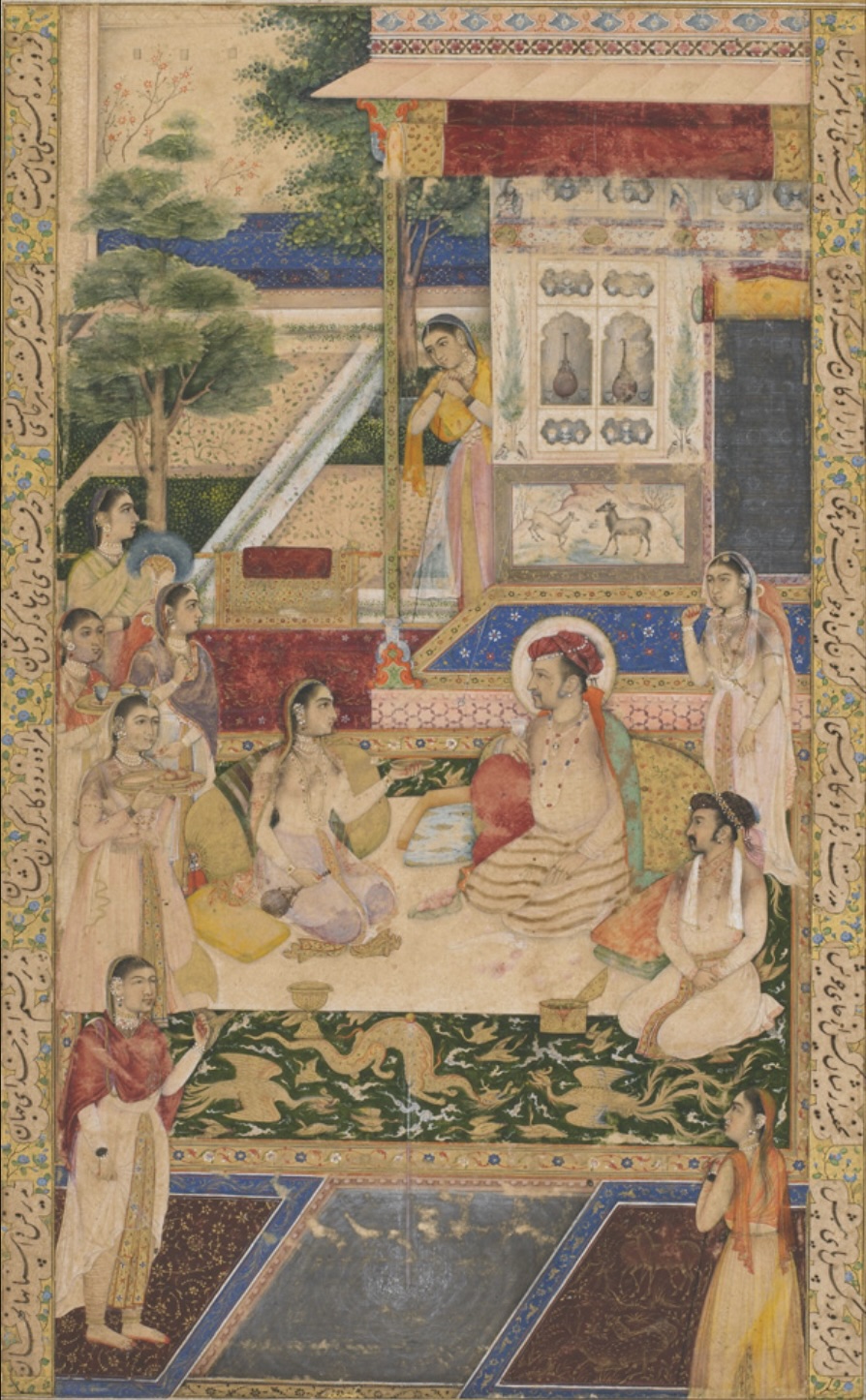

On 2 June 1602, after a voyage of fourteen months, the fleet reached Aceh (‘Achin’) in northern Sumatra. Lancaster and Towerson were greeted by an exhilarating sight. Here were collected ships from Gujarat, Bengal and Calicut, from Burma and Siam. The reputation of the English preceded them. In 1599, when John Davis visited with Cornelis de Houtman, Sultan Ala-uddin had entertained the Dutch with ‘excessive eating and drinking’, poison and treachery. Their ship was spared capture only after a stiff fight. The Englishman, however, had attracted considerable interest. The sultan was no friend of the Portuguese, and he had heard good things about Elizabeth’s wars with Spain. Happily, the letter which Lancaster now brought dwelt on Her Majesty’s rejection of Spanish and Portuguese claims to lordship in the East. It praised Achin’s valour, and its past successes against Malacca.[9]

The letter was placed on a salver of gold, covered with richly worked silk, and conveyed aloft in an elephant’s howdah. Lancaster and his officers followed on elephants of their own. To the sound of trumpets and drums, and amidst fluttering streamers, they proceeded to the palace through the press in the streets. There, Lancaster made obeisance ‘after the manner of the country’ and delivered his present,

… which was a Bason of Silver, with a Fountaine in the middest of it, weighing two hundred and five ounces, a great standing Cup of Silver, a rich Looking-Glasse, an Head-peece with a Plume of Feathers, a case of very faire Dagges (pistols), a rich wrought embroidered Belt to hang a Sword in, and a Fan of Feathers. All these were received in the Kings presence by a Nobleman of the Court: onely he tooke into his owne hand, the Fanne of Feathers: and caused one of his Women to fanne him therewithall, as a thing, that most pleased him of all the rest.

For entertainment, there followed banquets, arrack (‘a little will serve to bring one asleepe’ but Lancaster took his with water), dancing (by ‘Damosels … not usually seene of any, but such as the King will greatly honour’), and cockfights (‘one of the greatest sports this King delighteth in’). A grant of privileges was made. Lancaster was disappointed that the sultan would not bind his heirs and successors, as his negotiating draft proposed, but that was not the way of the Orient. Instead, Ala-uddin, ‘the reigning sovereign of the countries below the wind,’ instructed his people to trade with the English as with other foreigners. He promised his protection and freedom from custom dues.[10]

Of greater issue was the paucity of cargo. As the chronicler explains,

[Lancaster] was not a little grieved that Captaine John Davis, his principall Pilot, had told the Marchants, before our comming from London, that Pepper was to be had here for foure Spanish royals of eight the hundred[weight]; and it cost us almost twentie.[11]

Unfortunately, the principal ports for pepper were at Tiku and Priaman, on Sumatra’s western coast. At Achin, pepper was relatively scarce, and other Europeans had driven the price skywards. Recognising that it would put a ‘foule blot’ on his reputation if he returned without a cargo, Lancaster secured what he could for the Ascension, and sent the Susan to Priaman, to fill her hold at a cheaper rate. To replace the Susan, he bought a Dutch pinnace. Separated from her fleet on the journey from Holland, she had arrived in Achin with just three men and two boys to man her. This leads to the first direct mention of Gabriel Towerson:

During the time we were at Dachem, the king desired to have our pinnace goe to Pedeir, accompanyed with a Portugalles frigat, to take (if they might) rovers at sea, which did rob his subjectes; and did send to the valew of 100 markes in golde for those that should be imployed in that businesse. And because the general sent the pinnace, with 14 or 15 men (of whom Gabriel Towerson was captaine), but did no service, therefore the generall would have given the king that mony againe; but hee would not receive it by any meanes, saying what hee gave he gave and would not take againe.[12]

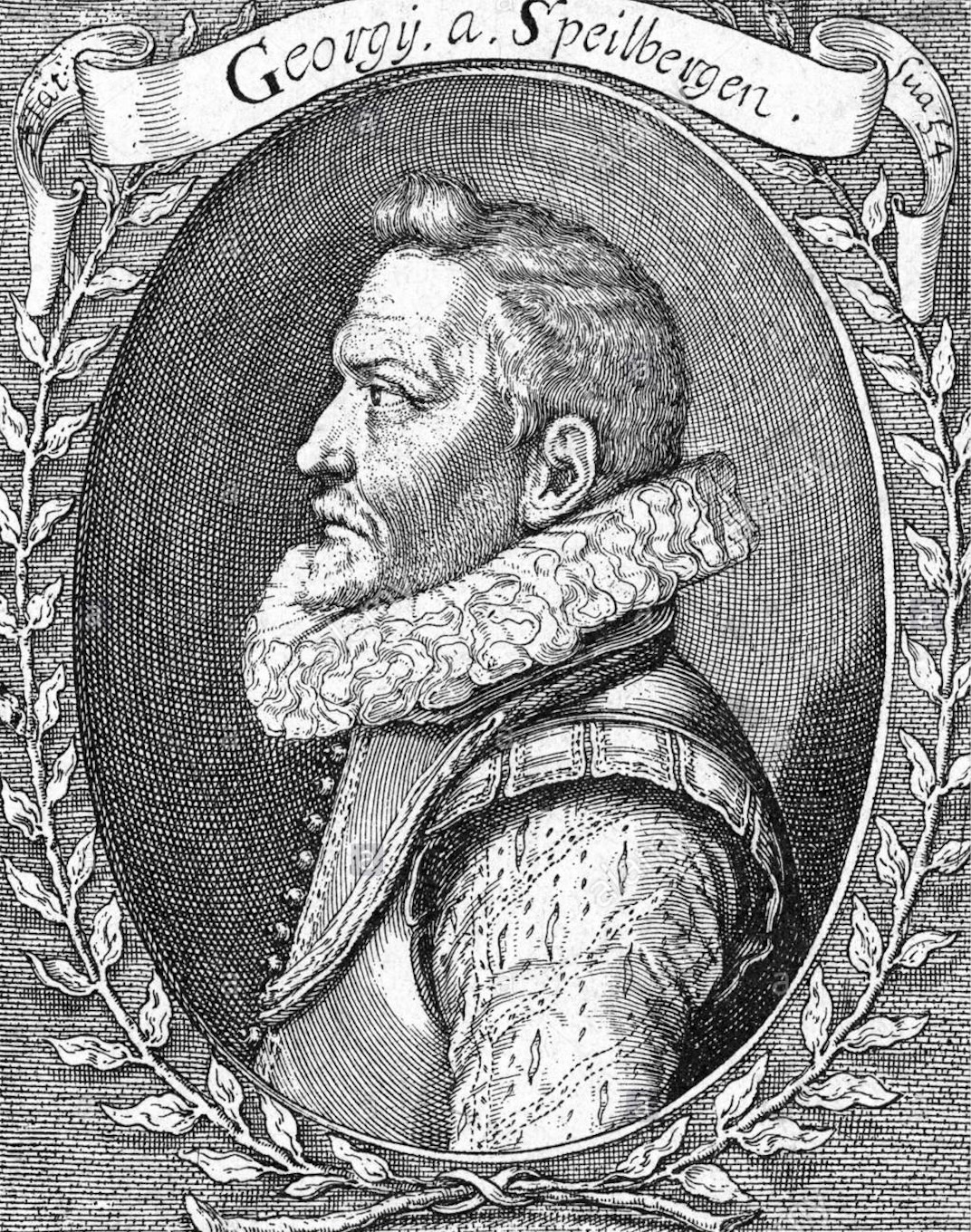

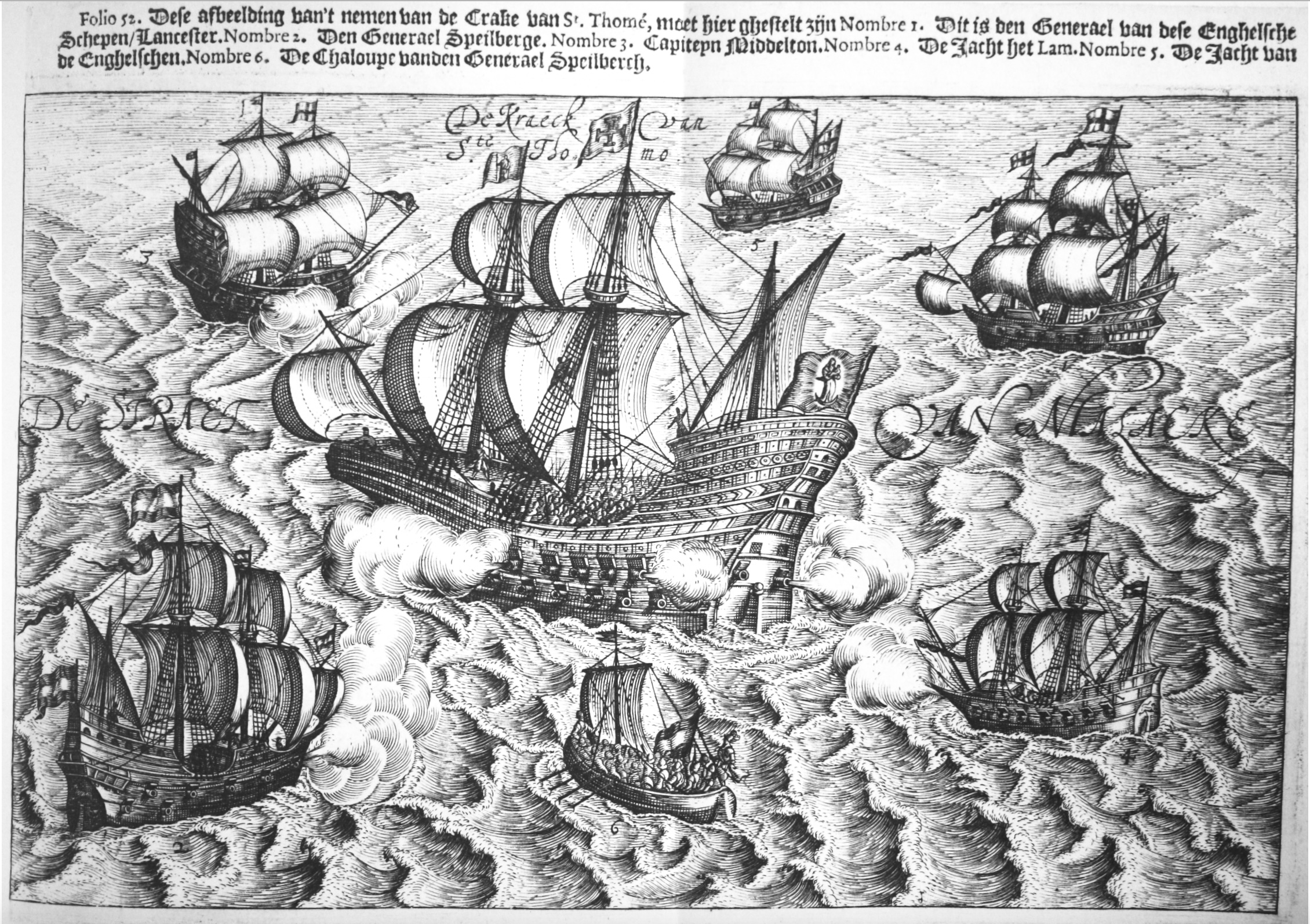

If Towerson was disappointed not to see action on this occasion, he was not to be so for long. Lancaster had been considering other ways of filling the Dragon and Hector. In early September, when Joris van Speilbergen, captain of the fleet to which the pinnace had belonged, arrived in Achin, Lancaster persuaded him to contribute his vessel, the Schaep, to an expedition against Portuguese shipping in the Straits of Malacca. If he showed unusual flexibility, first in cooperating with the Portuguese against pirates, and then in acting the pirate against them, so did Ala-uddin. He arrested two spies sent by their ambassador to warn Malacca of the attack. Later, in return for the promise of ‘a faire Portugall maiden,’ he detained the ambassador himself.

What followed was a repeat of the plan executed in 1592 when, off the Sembilan Islands in the Edward Bonaventure, Lancaster had ransacked a 700-ton Portuguese vessel from Goa. (This time, Lancaster drew on a ‘Commission for Reprisalls’ granted in England.) With the Schaep alongside, his fleet was formidable. They fanned out across the Malacca Straits, where,

… [on] the 3 day of October … the Hector espyed a great ship towardes evening, which came from S. Thoma and was bound for Malacca, and the next morning yeelded themselves without any resistance or so much as any one man hurt.

So wrote a merchant on the Ascension. Purchas’s chronicler states there was an exchange of gunfire before the Dragon ‘discharged sixe peeces’ and brought down the carrack’s main yard. Lancaster’s victim was the Santo Antonio. On board were six hundred men, women and children, and a rich cargo of calicoes, ideally suited to the Eastern market. Such was their plenty, they took six days to unload. Then, with a storm rising, the vessel was abandoned.

By this action, the value of the commodities which Lancaster might barter for spices was transformed: Indian cottons met with greater demand in Asia than English broadcloth. The approach was singular, but it confirmed the consequence of the regional country trade. Lancaster was not blind to its significance. Indeed, he was much bound to God, for

… he hath not onely supplied my necessities, to lade these ships I have: but hath given me as much as will lade as many more shippes as I have, if I had them to lade.[13]

The Santo Antonio’s passengers were left aboard her, and so Sultan Ala-uddin missed his fair maiden. He was not the only Achinese monarch to be disappointed so. In 1613, his grandson asked Thomas Best to send him two white women. If either bore him a son, he declared, he would make him king of the pepper producing region of Priaman, ‘so that yee shall not need to come any more to mee, but to your owne English king for these commodities.’ Amazingly, when this message was relayed to the London Committee,

… a gentleman of honourable parentage … [proferred] his daughter in marriage unto him, she beinge knowne to some of this Company to bee a gentlewoman of most excellent parts for musicke, her needle, and good discource, as alsoe very beautifull and personable.

After some debate, the committee consulted the elders of the Church. When they raised objections, the proponent of the enterprise produced counterarguments from the scriptures which were held ‘to bee very pregnant and good.’ He was not even greatly concerned at the possibility that ‘the rest of the women appertaining to the king may poison her if she becomes an extraordinary favourite.’ Eventually, the matter was referred to King James, the Directors minuting that ‘yf [the father] could worke His Majesties consent … yt would prove a very honourable action to this lande and his Majestie.’ Unsurprisingly, nothing more came of the idea.

In 1602, Lancaster displayed his diplomatic art. In lieu of a maiden, he gave Ala-uddin goods seized from the Portuguese. There were, he claimed, no damsels ‘so worthy, that merited to be so presented.’ His excuse was accepted with good grace.[14]

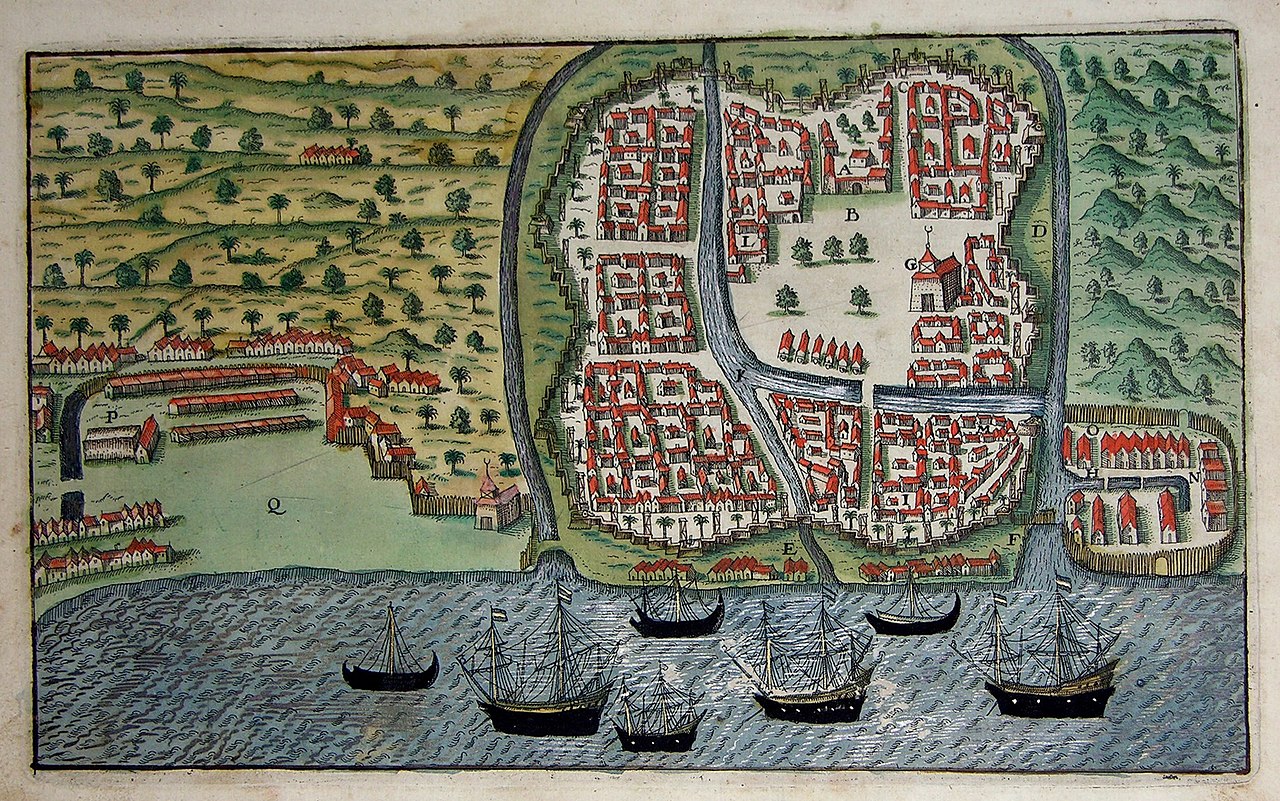

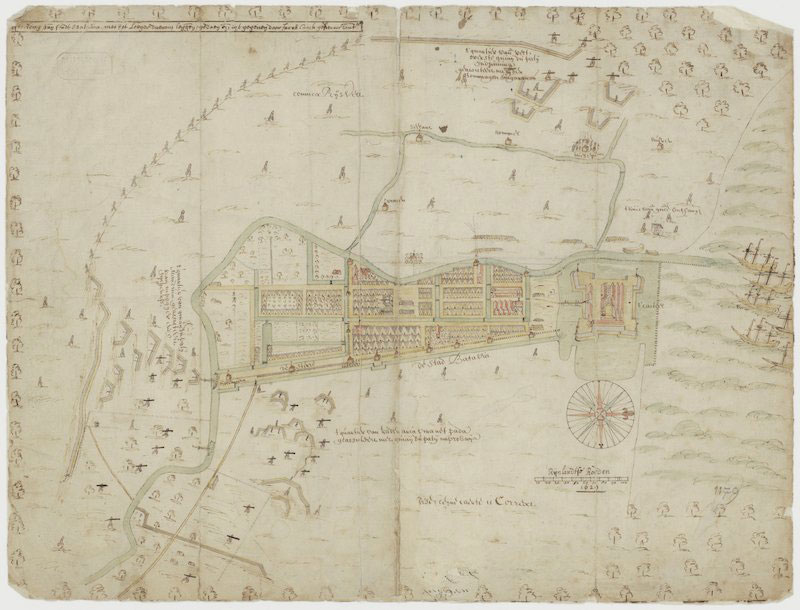

Lancaster now had more cargo than carrying space. From this, there arose the need for the Company’s first ‘factory’ in the Indies, to store the surplus for the next fleet. Still, it was important to find somewhere better suited than Achin. Lancaster resolved on Bantam, on Java, where the Dutch had a presence, and where the Chinese were frequent visitors. It promised a better market for the Company’s goods, and a supply of pepper at cheaper prices.

Lancaster took his leave of the sultan, who gifted Elizabeth a ruby ring and ‘two vestures woven with gold.’ In a letter, he confirmed his trade privileges and promised that any Spaniards he encountered would be publicly executed. Then, on a happier note, he and his nobles, and afterwards a choir of Lancaster’s crewmen, sang to each other some ‘psalms’. The Ascension was packed with as much pepper, cinnamon and cloves as she could carry, and sent to England. Taking the Dragon and the Hector, Lancaster joined the Susan at Priaman. Her lading was found to be almost complete, so he bid her farewell also, and made for Bantam, which he reached on 16 December 1602.[15]

Towerson in Bantam (1602-1608)

Bantam’s sultan proved to be a child of just ten or eleven, but the English soon obtained the trading concessions they desired, including factory premises of their choosing. They quickly attracted the interest of the local population. Purchas’s chronicler writes,

Wee traded heere very peaceably, although the Javians be reckoned among the greatest Pickers and Theeves of the World. But the Generall had commission from the King (after hee had received an abuse or two) that whosoever he tooke about his house in the night, he should kill them: so, after foure or five were thus slaine, we lived in reasonable peace and quiet. But, continually, all night, wee kept a carefull watch.[16]

The tactics were heavy handed, no doubt, but trade was good. Within five weeks, more had been exchanged in wares than Lancaster could lade on board. The only blot on this happy state of affairs was the death of John Middleton, captain of the Hector, who fell victim to Bantam’s pestilential climate. (He was the first of many.) It remained simply to appoint those who were to remain. Nine were selected, with William Starkey in overall charge, and Thomas Morgan and Edmund Scott in support. They were given discretion to do what they thought best, but Lancaster’s advice was to exchange the voyage’s goods as quickly as possible for pepper. Therein lay the best chance of defraying the factory’s expenses. There might be trading opportunities if visits by the Dutch caused prices to rise, but, under all circumstances, there were to be twenty thousand bags on hand when the Company’s ships next appeared. Lancaster warned, ‘You have the benefitt of 2 harvestes; I doubt not but you shall furnish the next shipps in good sorte.’

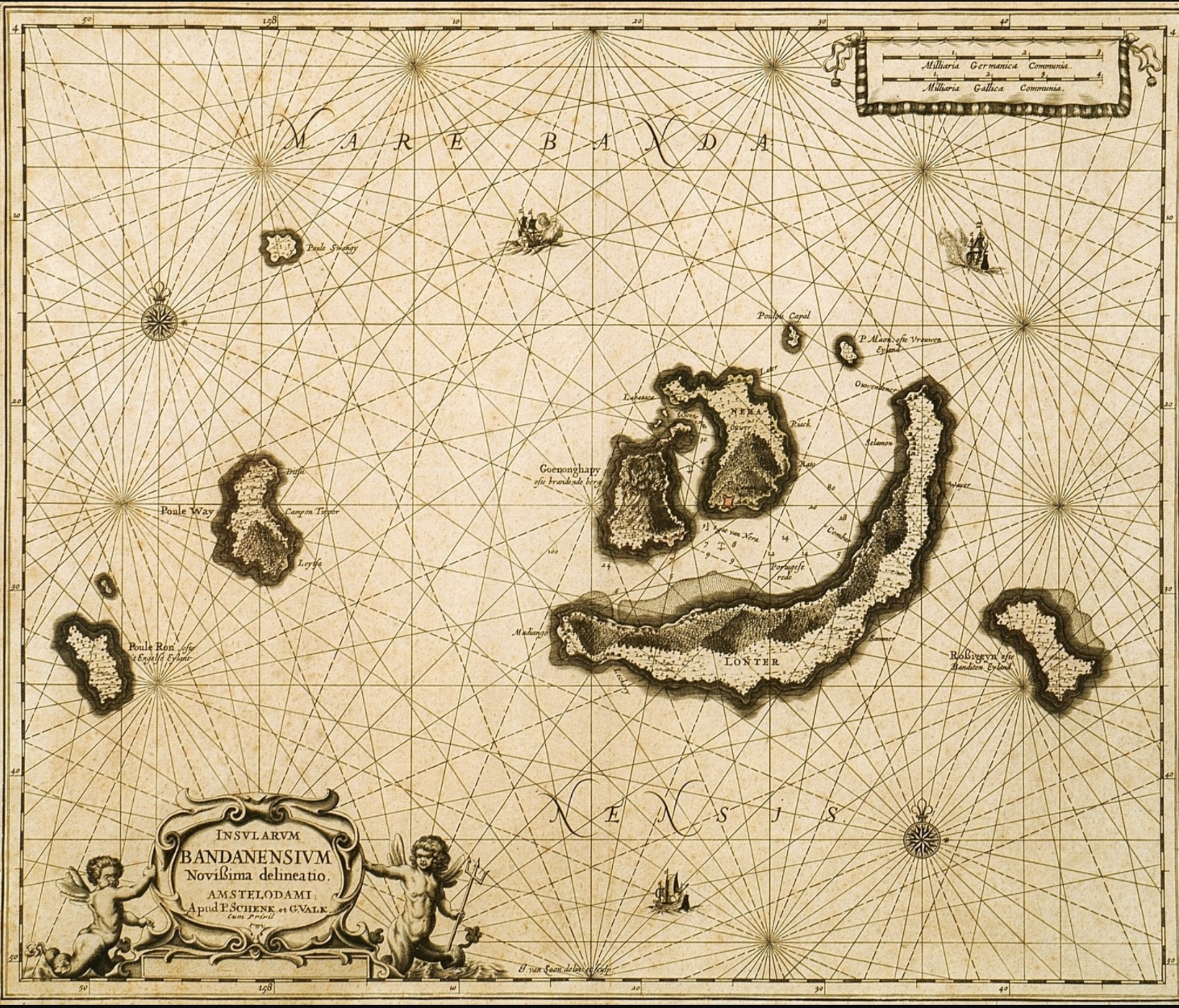

Gabriel Towerson’s first mission was to take the pinnace, with Thomas Tudd, William Chase, Thomas Dobson and Thomas Ketch, to the Isles of Banda, to trade cloth for nutmeg, mace and cloves. Lancaster anticipated that, for these spices, the Company would send two ships of six hundred tons in the next voyage, so they needed to be properly prepared:

Yt doth greatlie ymporte you to be carefull and pcure ladinge, for this is your whole busines there & therefor ar you sent. Alsoe, I would have you to agree together loveinglie like sober men, for your owne discordes yf you suppress them not, will be to the marchauntes greate losse and hindrance and to your owne undoing. Therefore Governe yourselves soe that there be noe brabbles amonge you for any cause.

Towerson and company were warned not to linger, and to take special care for their safety: of the people in those parts, it was said ‘their wholle bodyes and mindes be all treason.’ Departing on 6 March, by 28 April they were back, minus William Chase (who died), the rest weak and sickly. By reason of contrary winds, they had spent nearly two months ‘beating up and downe in the seas.’ Whether they made landfall remains a mystery.[17]

In Bantam, the factors dropped like flies. Thomas Morgan, long sickly, died on 25 April, James Howard on 10 May. The Bandas were abandoned and the pinnace was returned to Captain Speilbergen. Master Starkey was on his deathbed: it made little sense to leave affairs in the hands of just one factor and a dwindling number of assistants. When Starkey perished, on 30 June, Edmund Scott became chief and Gabriel Towerson his deputy. Thomas Dobson died on 17 July, Thomas Ketch on 17 August. With the death of Thomas Tudd, on 14 April 1604, just two of seven factors remained. Including native workers, the factory was operated by ten men and a boy.[18]

Disease was not the only challenge. Visitors from the Sumatran side of the Sunda Strait had developed the habit of breaking into the Javans’ houses, stealing their women, and slitting their throats. One dinner time, the wife of a neighbour was killed in this way, despite English efforts to save her. Scott complains that, for a month afterwards, he was unable to sleep, because of the lamentations of the people next door. He adds that there were Javan women, some of whom lingered about the factory, who decapitated their husbands, if foreign, and donated the heads to the kidnappers. Associates of the sultan were offering rewards for such specialties. Not that this always involved bloodletting: on occasion, the corpses of the recently buried were exhumed and their heads used to ‘coussen’ the ruler.

Kidnap was not uniquely a Sumatran practice. On one occasion, some Chinese hid the wife of a neighbour in the factory’s pepper store, the door of which had been left open in the heat of the day. That evening, she was discovered when she surfaced to get some air, ‘for shee had beene better to have beene in a stove so long.’ It being considered strange to find ‘such cattell’ within the precincts at night, she was taken to Scott, and examined. She said she had been hiding for fear of being beaten by her husband. Scott was unconvinced. He suspected she was an incendiary. The factory was searched. When nothing was found, he presumed she was a whore, secreted away by one his men. Only after he was persuaded that even this was not so did he conclude she had been telling the truth. It was, he writes, common for the Chinese to beat their wives, especially if they were Cochin Chinese, as she was. The following morning, her husband appeared, begging Scott not to discipline him. Scott saw no need. The Chinaman, he writes, ‘needed no more plague or punishment then such a wife.’ He dismissed them both.

In case Scott appears unreasonably suspicious of attempts at arson, his fears might be put into context. The timber and rattan fabric of Bantam’s buildings made them highly combustible and, from the first, some Javans were unfriendly:

[They] began to practise the firing of our principall house with firie darts and arrowes in the night. And, not content with that, in the daytime, if we had brought out any quantitie of goods to ayre, we should be sure to have the towne fiered to windward not farre from us. And if those fierie arrows had not, by Gods providence, been espied by some of our owne house (as they were), it was thought of us all that that house and goods had been all consumed; as might plainly appeare at the toppe, when we came to repaire it.

Within a month of Lancaster’s departure, sixty-five fardels of goods and pepper were destroyed ‘by reason of a Chyna captaine that shot a peece.’ This set the town ablaze, and burned the Dutch establishment, in which some of the Company’s goods were stored, to the ground. The windows in the partially complete, English factory became too hot to touch. That its thatch did not catch light was a wonder to those who came to seize their opportunity. Scott wondered at their boldness. Many times, he wrote, ‘they would come and looke, before our faces, how our doores were hanged and what fastening they had within.’ At night, he and Towerson set an armed watch. Their vigorous defence earned the respect of those ‘thinking to have executed their bloodie pretence’:

The Javans perceiving they could get nothing at our handes but lead, the which they had had many times before and founde it to bee a mettall too heavie for them, they began now to fall to worke with the Chyneses, whose houses at this time were full of our goods which they had bought … Many Chyneses about us were slaine; and surely, if wee hadde not defended them with our shotte, many more would have been slaine; for the singing of a bullet is as tirrible to a Javan as the cry of the hounds is in the eares of the hare.

Later, in May 1604, a Chinaman who operated an arrack distillery next to the English palisade, turned ‘ingyner’. He recruited ‘eight fyrebrands of hell’ to dig a tunnel under the compound, to the warehouse. For two months, the plotters awaited a chance to cut their way through its wooden floor. (They did not know that, in the building closest to their own, there were thirty thousand rials buried in jars but otherwise unprotected.)

Well [Scott writes], one of theis wicked consortship, being a goldsmith and brought up alwaies to work in fire, told his fellows he would work out the plankes with fire, so that we should never heare nor see him. Little did he think so that we should ever come to worke with fierie hot irons upon him …

Of course, the fire took hold. At first, the English were puzzled by the stench of smouldering sacking. Then, smoke found its way through a rat’s hole into the kitchen above:

[Scott] ranne downe and opened the doores; wherat came out such a strong stinke and smoake that had almost strangled us … And all that time wee had twoe great jars of powder standing in the warehouse; which caused us greatly to feare blowing up. Yet, setting all feare aside, wee went to it, and plucked all things off that lay on them (which feeled in our hands very hott) … Wee plucked our packes so fast as wee could, but, by reason of the heat and smoake which choaked us, beeing so few as wee were, could doe little good uppon it; wherefore wee let in the Chyneses. Then came in as well those that had done it, as others, hoping to get some spoyle …

The advice of the Chinese was to break down the ceiling and pour in water from above, but to expose the smouldering sacks to air risked making matters worse. There was insufficient water: if the flames took hold, it would have been impossible to save even a groat’s worth of stock. Their next suggestion was to break down the exterior wall. This Scott dismissed, as a transparent attempt to make the theft of his packs easier:

Maister Towerson and myselfe, wee had worke enough to stand by with our swordes, to keepe them from throwing them over the pales after they were out; also they were not without their consorts on the other side to receive them.

Then, Scott remembered that he had left £1,000 in gold in a chest upstairs. Resolving to cast it, for safety, into a pond at the back of the compound, he rushed inside, only to discover his neighbour in the dining room. He and his confederates had removed the table and were breaking through the brickwork floor. Scott let fly, and only with difficulty was he able to eject them.

Eventually, with the help of some Chinese, the warehouse was cleared of its stock and the fire was extinguished. It left the compound looking ‘like a small towne that had beene newly sacked by the enemie.’ What had caused the conflagration remained a puzzle until another hole was found. Scott called for an axe, wrenched up the planking and found a tunnel ‘that the greatest chest or packe in our house might have gone downe.’ Three men were apprehended in the hostelry next door (two others escaped).

As Scott surveyed the wreckage, some Chinese sought to give him comfort. He was in an unforgiving mood:

[They] tolde mee I did not give sacrifice to God, wherefore this mischaunce was happened unto mee. I tolde them I did give sacrifice to God everie day, but not after their manner, nor never would. But had wee knowne then that the Chyneses had done it, wee should have sacryfised so many of them that their bloode should have helped to have quenched the fire.

The Dutch promised more concrete support, and neither they, nor Scott, were squeamish. The first of the captives was persuaded with branding irons to confess his involvement. The goldsmith was a harder nut to crack. He was known as a counterfeiter of coins and, since there was but one way with him, he confessed nothing:

Wherefore, because of his sullennesse, I thought I would burne him now a little (for wee were now in the heate of our anger). First, I caused him to be burned under the nayles of his thumbes, fingers and toes with sharpe hotte iron, and the nayles to be torne off. And because hee never blemished at that, we thought that his handes and legges had beene nummed with tying; wherefore wee burned him in the armes, shoulders and necke. But all was one with him. Then wee burned him quite thorow the hands, and with rasphes of iron tore out the flesh and sinewes. After that, I caused them to knocke the edges of his shinne bones with hotte searing irons. Then I caused colde scrues of irone to bee scrued into the bones of his armes and sodenly to bee snatched out. After that all the bones of his fingers and toes to bee broken with pincers. Yet for all this hee never shed teare; no, nor once turned his head aside, nor styrred hand or foot; but when wee demaunded any question, hee would put his tongue betweene his teeth and strike his chynne upon his knees to byte it off.

In desperation, Scott had the counterfeiter put into irons, and left so that white ants could get into his wounds. With satisfaction, he says, ‘they tormented him worse than wee had done, as wee might well see by his jesture.’ Then the sultan’s officers intervened. Conceivably, they were squeamish. They insisted that the victim be shot. When Scott declared their treatment too lenient, they swore it was the cruellest death of all. The English ensured it was so:

… in the evening we led him into the fields and made him fast to a stake. The first shott caried away a peece of his arme bone, and all the next shot struck him through the breast, up neare to the shoulder. Then he, holding downe his head, looked upon the wound. The third shotte that was made, one of our men had cut a bullet in three partes, which strooke upon his breast in a tryangle; whereat hee fell downe as low as the stake would give him leave. But betweene our men and the Hollanders, they shot him almost to peeces before they left him.

Gabriel Towerson was surely as active a participant in these events as any. Much later, when a fourth of the conspirators had been executed, but others remained at large, Scott wrote,

I doubt not but Maister Towerson will doe his best to get them hereafter; for hee and I both, if wee live this hundered years, shall never forget the extreame horror and trouble they brought us to.

It happened that the fourth victim of English justice had a relatively happy time of it. There was other pressing business: otherwise, Scott says, ‘he should have died nothing so easie a death as he did.’ Even so, those that live by such retribution, may perish by it …

In the ‘ingyner’ incident, the Dutch supported the English. However, there was much rivalry, and, on occasion, they came to blows. The Dutch were not unprovoked. In one episode, one of Scott’s men fired his musket skywards and the ball ‘fell downe in one of the Hollanders outhouses through the thatch.’ When some Malays complained that they preferred to take their meals in safety, the Dutch took aim at the English quadrangle from an upstairs window. Three shots narrowly missed Scott, so his complaint was remarkably mild-mannered. ‘Wee blamed them much for doing so in such a dangerous time,’ he wrote, ‘although they meant us noe hurt.’

The crimes of one of the Englishmen’s native servants bore particularly hard. ‘Beeing somewhat tickled in the heade with wine,’ this character killed a Dutch officer for beating one of his crewmen, a drinking companion. The servant then murdered the companion (for fear of betrayal) and, ‘being nuzled in bloud,’ an innocent passer-by. Scott wished to settle the issue of blood money with Bantam’s governor before executing him, but the Dutch insisted that, immediately,

… hee should have the bones of his legs and armes broken, and so he should lye and dye; or else have his feete and hands cut off, and so lye and starve to death.

The dispute culminated in an embarrassing contretemps at the palace, during which the governor, fearing that the English and the Dutch ‘would have gone by the eares,’ suggested that the sultan might absent himself. After some debate, the servant was executed using the traditional method among the Javans: by stabbing. As he lay gasping on the ground, Scott warned the Dutch witnesses that ‘that was the fruite of drunkennesse, and byd them ever after beware of it.’[19]

These events apart, the Dutch were jealous of the Company’s two-storey factory, and irritated by the governor’s refusal, early on, to grant an equivalent. They were annoyed by the better terms the English obtained from Chinese merchants, and, on more than one occasion, they were caught paying bribes to their ally in the administration, for favourable treatment in obtaining supplies of pepper. Scott countered these efforts, not always successfully, by working on allies of his own: the harbourmaster, the commander of the sultan’s galleys, and the ‘Old Queen’, a wife of the former ruler, who retained influence. When the Dutch tried to dupe him into sharing pepper and bad debts in equal proportion, Scott penetrated their ruse. He claims English debts were ‘all sure, except some small driblets,’ but the Dutch were mostly owed by Javans ‘and great men too, so that God knowes when they will bee paide.’

Overall, he believed that the English had the better reputation amongst the Bantamese, for all that the Dutch had the greater presence. A high-handed approach made them unpopular, and the English were anxious not to be confused with them. That is why, in November 1603, the English prepared a special parade:

Wee all suted ourselves in new apparrell of silke and made us all scarffs of white and redd taffeta (beeing our countries cullours) … [and] set up our banner of Sainct G[e]orge upon the top of our house, and with our drumme and shott wee marched up and downe within our owne grounde …

The Sabynder and divers of the chiefest of the land, hearing our peeces, came to see us and to enquire the cause of our triumph. Wee told them that that day sixe and fourtie yeare our Queene was crowned; wherefore all Englishmen, in what countrey soever they were, did triumph on that day. Hee greatly commended us for having our prince in reverence in so farre a countrey. Many others did aske us why the Englishmen at the other house did not so. Wee told them they were no Englishmen, but Hollanders, and that they had no king, but their land was ruled by governours …

Scott says that he had some doubts about the wisdom of this plan ‘for feare of being counted fantasticall,’ but that ‘the perswasions of Thomas Tudd and Gabriel Towerson, and chieflie the present danger wee stood in, forced mee to it.’

Relations with the Dutch were at their most antagonistic when ships were in the harbour. Samuel Purchas appends to Scott’s journal an account of some broils which led to the loss of limbs, and a few deaths. After describing one battle in an arrack house, he claims that,

These frayes were greatly admired at, of all Nations in that place, that we should dare to bandy blowes with the Flemmings, they having seven verie tall ships in the Road, and we but two.

This particular fracas occurred shortly before Henry Middleton, commander of the Second Voyage, arrived with the Dragon and Ascension, in December 1604. Purchas’s account ends with the Dutch and English shaking hands, and, in truth, the English had much to be thankful for. Whenever the threat from the natives become serious, the Dutch rallied to their cause. Had they not done so, the factory might not have survived. Scott says, ‘although wee were mortall enemies in our trade, yet in all other matters wee were friends, and would have lived and dyed one for the other.’ Even so, it gave him pleasure to report that, at a celebration before Middleton’s departure for the Moluccas, ‘the Hollander’s tooke the licker so well that they were sicke on it most part of the weeke following.’ He believed this gave Middleton a head-start, which was ‘greatly to our Generals advantage.’[20]

In October 1605, Scott departed with Middleton’s returning fleet, and Towerson took his place. His salary was £6 per month. Middleton cautioned that the establishment needed greater care: goods left lying around were a fire hazard, and treating them so would ‘both roote them, and breed wormes in them.’ He advised that everything, including the items he had bought for resale in the Moluccas, should be given an airing at least once a month, and that perishable merchandise should be exchanged for money, or pepper (if it could be sold free of cleaning costs). With that, an injunction to be friendly to the Dutch ‘although the meaner sorte of them be rude,’ and a directive to attend to twice daily prayers, he sailed for England.[21]

John Saris now becomes our principal source for events. Unfortunately, he shares neither Scott’s quality of reportage nor his felicity of language. Mostly, he tells of the growth in the VOC’s network and power. Beside it, the Company’s operation looks increasingly meagre. One senses the tension building. Of the daily lives of the English, he gives few clues. Fires remain a problem, although there is less mention of the fear which caused Scott to write,

… what with overwatching and with suddaine waking out of our sleepe (wee beeing comtinually in feare of our lives), some of our men were distract of their witts.[22]

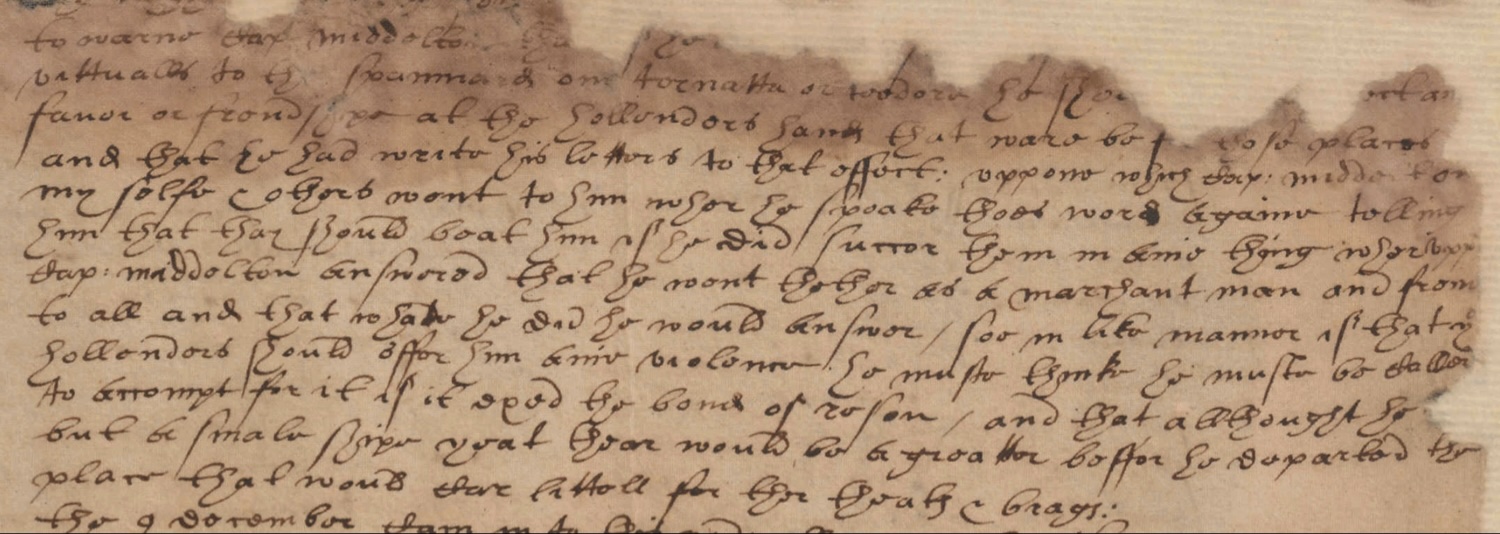

One vignette involves Sir Edward Michelborne, the ‘gentleman’ who had been discharged from the Company in 1601, for failing to honour his dues. He sailed to the Indies, in 1605-1606, under a personal warrant of King James, but with an eye on plunder. In October 1605, the Dutch reported that, in the Straits of Sunda, he had seized a Gujarati junk. Towerson and Saris were summoned to explain why the English were attacking vessels belonging to the friends of the sultan. They were unaware of Michelborne’s presence, so they suggested that either the report was ‘fabulous’, or the Dutch were responsible. A week later, Michelborne arrived at Bantam. Over dinner, he confessed his crime. Saris says that he was persuaded ‘as he was a Gentlemen’ to leave the junks of the Chinese alone. But Michelborne was not a gentleman. To the embarrassment of all, a few weeks later, there arrived ‘a China juncke, which Sir Edward Michelborne had taken, and restitution was demanded of us.’ Later still, in February 1606, the captain of a Dutch fleet encountered Michelborne near Sumatra. He explained that the …

… English Merchants in Bantam were in great perill, and that still they looked for nothing else, then that the King of Java would assault them, because they had taken the China ship, whereby the King of Bantam had lost his custome.

He tried to persuade Michelborne to return to Europe with him, but Michelborne would have none of it.[23]

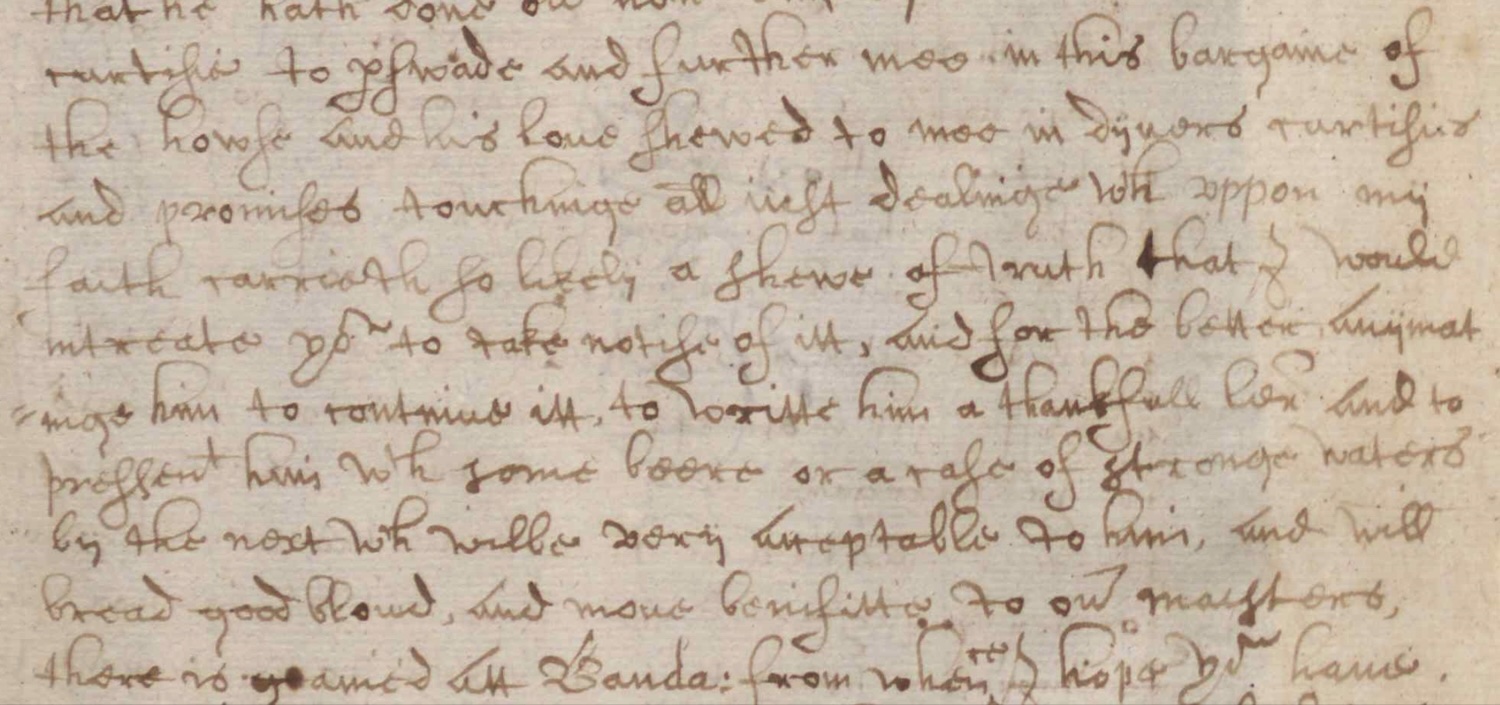

After this, there is little word of Towerson. The main exception is a letter he sent to his brother, on 30 April 1607. In it, he gave a detailed account of Cornelis de Matelief’s attack on Portuguese Malacca, explaining that it spared the Dutch and the English from being turned out of Bantam. Then, on 14 November, Middleton’s younger brother, David, representing the vanguard of the Company’s Third Voyage, arrived in the Consent. He found everything in good order but, typically, his stay was brief. Towerson introduced him to Matelief, who warned that the Dutch ‘should beat him’ if he assisted in any way the Spanish on Ternate or Tidore. Middleton cared little for Dutch ‘threats and brags.’ He unloaded his iron and lead and, after ‘some roomaging’ in the Consent’s hold, he left on 6 December. True enough, in the Moluccas, the Spanish tried to force his hand: they denied him permission to trade, unless he helped them against the Dutch. Middleton refused. He said it was forbidden by his commission. Instead, he relied upon ‘privy trade with the people by night’ until, after a few days, that too was countermanded. Having secured only a modest cargo, he transferred to Butung (‘Button’), in Sulawesi. There, the warlike Bugis smuggled to him cloves from Amboyna in their prahus, beyond the gaze of the Dutch patrols. By 22 May 1608, Middleton was back at Bantam, and, by 15 July, he was gone.[24]

The arrival at Bantam of William Keeling, commander of the Third Voyage, in September 1608, coincided with a palace coup. The governor was killed by his enemies, who,

… beset the Court, first laying hold of the King and his Mother; and then they ranne into the Governours Court, thinking to have found him in bed, but he was on the backeside his bed, where they found him, and wounded him first on the head, whereupon he fled to the Priest called Keyfinkkey, who came forth and intreated them for his life, but they would not be perswaded, but perforce ran in, and made an end of him.[25]

These developments echoed political strife during Scott’s time. Then, the chief agitator had been Pangeran Mandalika, who had been supported by a deposed sultan of Jakarta. When, in September 1604, the pangeran came to spy out the English factory, Scott took pleasure in informing him of his preparations for defence:

Wheresoever wee were, I told him, our dogs lay alwaies readie, belowe the most parte of them, and wee had some above too. Your dogs, said hee, which are they? Then we pointed him first to one peece, then to another; and indeed we had a dosen stood very orderly. Said he: call you them dogs? Wee tould him they would barke if occasion served.[26]

Given that the governor deposed in 1608 was a venal fellow, who had favoured the Dutch, and his opponents had been Scott’s backers, the new developments should have been to the Company’s advantage. Unfortunately, this was not so. The Bantam factory’s trade declined. In a note he added to his account of David Middleton’s next visit, in December 1609, Purchas commented,

By the alteration of State, their debts were almost desperate, nor would this Governour suffer them (as before) themselves to imprison debters, and distraine. He also exacted unreasonable summes for rent, whereas the ground had been given, and the houses built at the Companies charge.[27]

By this time, English involvement in resistance to the VOC in the spice islands was getting under the Dutchmen’s skin. Later, Towerson fell victim to their displeasure. Now, he enjoyed a period of leave. Keeling departed Bantam on 4 December 1608, but he quickly returned, having encountered the Hector, the third of the ships of the Third Voyage, in the Straits of Sunda, minus her captain (William Hawkins, who had landed in India) and minus several of her crew, who had been captured by the Portuguese. Earlier, Towerson had sought London’s permission to return home. When he reiterated his request, Keeling transferred his flag to the Hector. As he steered for the Bandas, Towerson took the Red Dragon to England.[28]

John Saris’s Eighth Voyage (1611-1614)

She arrived at Plymouth, in September 1609, leaking and ‘in want of many of her men.’ At royal insistence, her cargo of pepper was sold to King James, who reinstated the Company’s monopoly, in November. In December, the Directors minuted,

Seven cwt. of cloves and all other things belonging to Gabriel Towerson to be delivered to him, except his pepper, for which the Company give him 1s. 6d. a pound, and pay the custom.[29]

For context, in their commission to Keeling and David Middleton, of March 1606, London had given ‘expresse order’,

… for examination of our factors dealeing att Bantam in our generall accompte & other wayes, & also of all their private trade, used since their going thither: Wherein we understand mr Towerson hath beene a lardge dealer for him selfe, haveing sould to the Hollenders att one tyme 300 sackes of pepp besides other thinges very straungge unto us.

To Towerson and the factors themselves, the Directors had objected,

Wee utterlie dislike of your pticular advice to your private friendes either of what Comodities are theare requested, or theare alsoe to be had, or of the prices, wherein you are altogether verie sparinge to advice the Gouvernor & Companie in your generall lettres unto them …[30]

Towerson drops out of the record for 1610, re-emerging only in April 1611, when he commanded the Hector in John Saris’s Eighth Voyage. As the Directors’ ‘loveinge friende’, he was appointed second-in-command, which suggests his misdemeanours had been forgiven. Although the voyage is best-known for Saris’s onward journey to Japan, its principal objective was Surat, on India’s west coast, where Henry Middleton was assumed to be building on William Hawkins’ lead in establishing a factory. If Saris missed the monsoon, he was to go to Aden or Mocha and explore its potential, before travelling to Surat the following year. This is what he did, although the onward voyage was disrupted by Middleton’s depredations against Indian shipping.

When they resumed, relations between Saris and Towerson began tetchily: Saris may have been asserting his authority over the man who had been his superior in Bantam. The mood was set, on 6 April, before the fleet left Gravesend, when Edward Camden reported that the pass of the Ottoman emperor had been ‘stolen’ whilst he was ‘making merrye’ with his friends. When, four days later, Towerson reported that some of his crew had tried breaking into the hold, to steal cargo for sale locally, Saris’s temper snapped. Towerson was told he was being over familiar with his men, and to enforce proper discipline. It was highly unfortunate, therefore, that on 12 April, the Thomas was almost set ablaze due to carelessness in the galley. Saris’s language, when he called Towerson to account, might easily be imagined. It was fortunate, therefore, that the journey to the Gulf passed free of incident.[31]

Saris’s adventures there will shortly be told in connection with William Hawkins. They will not be repeated here. Suffice to say, there was argument between Saris and Middleton over the division of spoils, and Towerson was involved in the negotiations. Separately, he was charged by Richard Cocks with taking into his possession two bales of indigo, which Cocks claimed had been gifted to him by a Persian. At Priaman, in August 1612, he was accused of worse by John Jourdain. Jourdain sent William Pemberton for news of Middleton:

… but Captaine Towerson … made him doubt much of the Generall’s comeinge, sayinge that he heard that hee was to lade pepper and indico at Dabull and to departe for England from thence; urginge him to sell the pepper which he had bought to him, and to goe with our shipp in his companie to Bantam, because our shipp was so leake, eaten with wormes, thatt wee durst nott adventure to lade her with pepper, beinge very leake between winde and water; which Captain Towerson understandinge, used this policy to gett the pepper from us …

Jourdain says he was wise to Towerson’s knavery and that he refused the offer. He adds that, although his ships were short of many necessities, Towerson denied them succour: the Hector sailed for Bantam ‘leavinge the Thomas at Priaman, and the Darlinge at Tecoo, very leake, many of our men dead and many remayneinge sicke, with small store of victualls.’ Sorting a way through this claim and counterclaim is difficult. Rivalry between voyages was a consequence of their being financed separately: antagonisms of this kind did not end until the First Joint Stock of 1613-1616. Jourdain’s complaint contrasts with the assistance given by Towerson to Nicholas Downton at the Cape, during the voyage home. For this, Downton ‘was much beholden.’ By then, however, the Hector had a full cargo.[32]

When Towerson resumed his journey from there, he took with him an interesting curiosity. Two Saldanian natives made the error of visiting the Hector as she was preparing to depart. Towerson detained them, thinking that, once they had learned some English, they might assist in the obtaining of supplies. Looking back, Edward Terry, a chaplain in Benjamin Joseph’s voyage of 1616, had sympathy enough to consider them ‘poor wretches.’ His compassion went only so far, however. When one of them died shortly afterwards, he ascribed his fate to ‘extreme sullenness’, adding that he ‘was very well used.’ The other reached London, where he was lodged, in some style, at the house of the Company’s governor, Sir Thomas Smythe. Terry found it puzzling that Coree did not consider his new circumstances ‘an Heaven upon Earth.’ ‘He had good diet, good cloaths, good lodging, with all other fitting accommodations’:

[But] though he had to his good entertainment made for him a chain of bright brass, an armour, breast, back, and head-piece, with a buckler, all of brass, his beloved metal; yet all this contented him not … for when he had learned a little of our language, he would daily lie upon the ground, and cry very often thus in broken English, ‘Coree home go, Souldania go, home go.’

After six months, Coree was granted his wish. Terry writes,

… he had no sooner set footing on his own shore, but presently he threw away his cloaths, his linen, with all other covering, and got his sheeps skins upon his back, guts about his neck, and such a perfum’d cap (said to be made from cow-dung) … upon his head; by whom that proverb mentioned, 2 Pet. 2, v.22, was literally fulfill’d, Canis ad vomitum; ‘the dog is return’d to his vomit, and the swine to his wallowing in the mire.’

Terry, apparently, had no high opinion of Saldanian hygiene. In the end, he decided it would have been best if Coree had never visited England, for he had learned the true value of the brass which the English bartered for their supplies. Never again were cattle and sheep to be obtained as cheaply as James Lancaster had found them, in 1601.[33]

Quite when the Hector reached England is unclear. It was probably before Downton reached Waterford, in September 1613, and it was certainly before 21 February 1614. Then, at Saint Nicholas Acons Church, Towerson married Mariam, the widow of William Hawkins, who had perished with most of the men of the Thomas on the homeward journey.[34]

Mr. and Mrs. Towerson in India (1614-1619)

Almost immediately, the Towersons became involved with Company claims on Mariam’s first husband, and an investigation into Gabriel’s private trade. The Court Minutes for the Company, for 18 January 1614, refer to:

‘A meeting of committees for Capt. Towerson’s business.’ His demands to be gratified for good service and bringing the Hector safe home; a breach of commission alleged against him, and forfeiture of £1,000 bond for private trade; debate whether he should be punished; resolution to remit his offence, but to make him pay freight for his goods. His bond to be detained till the return of Capt. Saris, who commanded him. Says he will be contented with any end they think fit to make.

On 11 February, the Directors decided that, in view of his ‘deficiencies’,

… the Company cannot allow the extraordinary charges of [Mrs. Hawkins’] husband: ‘although he had esteemed himself one of the ‘Grand Magore’s followers’, his salary of £200 a year amounts to £700, and £300 allowed for bringing his wife and household down to Surat.

However, as the Towersons undertook to comply with their award, the Directors, ‘being charitably affected towards the widow, who is to be married very shortly,’ agreed to present her instead with ‘a purse of 200 jacobus, as a token of their love.’

On 17 February, there was a setback when Nicholas Ufflett made certain revelations about Mrs. Hawkins: that she had one diamond worth £2,000, more worth £4,000, and other precious stones. Ufflett promised additional intelligence on Captain Hawkins’ proceedings, which the governor charged all to keep secret.[35]

On 21 February (the Towersons’ wedding day), it was decided to honour the earlier award of 200 jacobus against ‘a general release by Capt. Towerson and his wife of all matters against the Company and Sir Henry Middleton.’ Towerson received payment for his adventure, on 3 March. The couple were not yet in the clear. Subsequent minutes refer to ‘a report of the auditors on Capt. Towerson’s business’ (July), to a ‘request of Capt. Towerson to be freed from a debt to Don Lewis, a Portugal’ (November) and to a request, made by Towerson, to have his accounts referred ‘to three of the committees’ (April 1615).[36]

On the plus side, on 28 September 1614, there is a reference to the ‘admission of Capt. Towerson … gratis, for long service.’ On 28 April 1615, another to ‘Capt. Towerson’s business ended concerning payment of freight and a debt’ (presumably to Don Lewis), although there remained a ‘question as to a parcel of indigo’ (presumably that claimed by Cocks).[37]

In June 1615, Towerson put in a request to command another voyage. It was referred to George Bennett but refused. The minutes for 25 September refer to ‘reasons for declining the request of Capt. Towerson to be entertained for another voyage.’ His private dealings needed to be clarified first.[38]

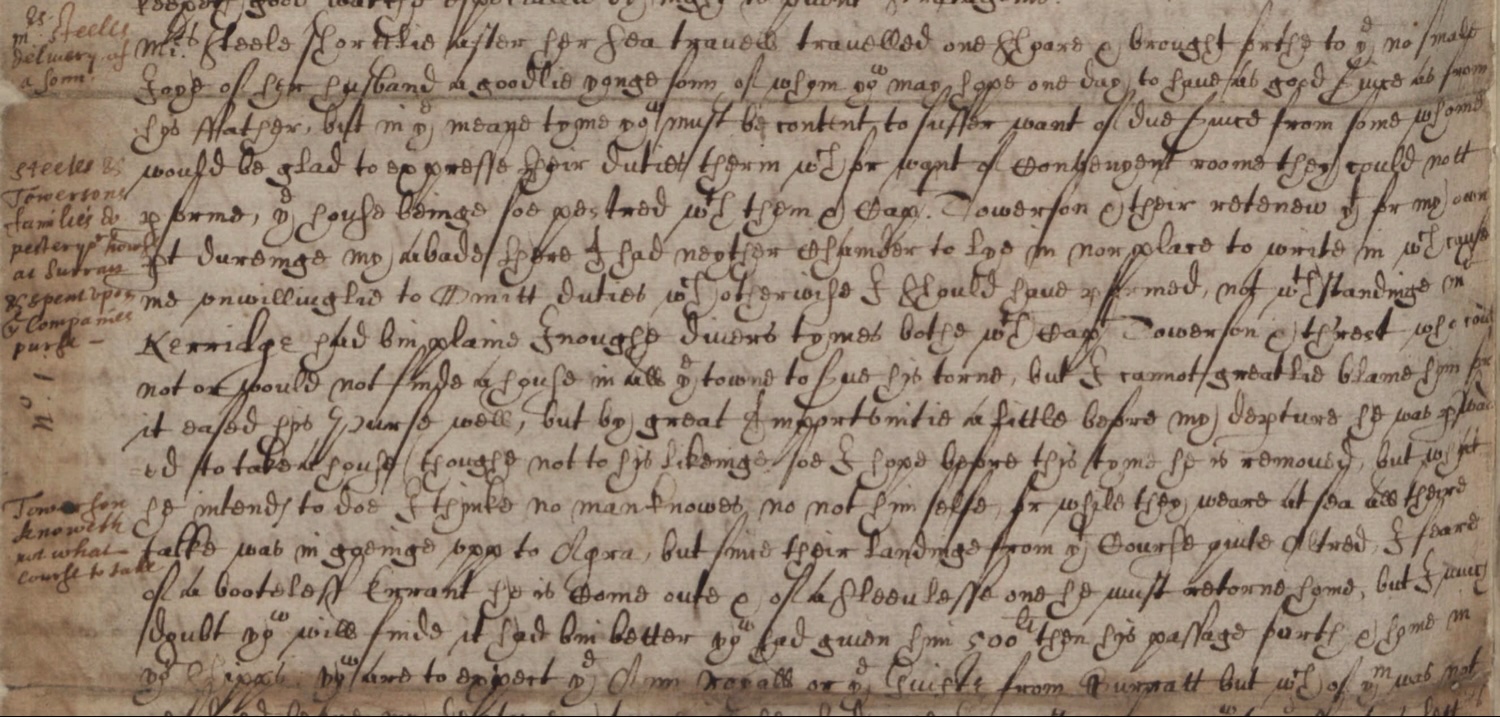

Mrs. Towerson was an Armenian who had married Hawkins in India, at the suggestion of Emperor Jahangir. The newly-weds now persuaded the Company to grant them passage, so they might use her wealth and connections to further their fortune. As a rule, the export of women to India was not encouraged, but Mariam took a friend, Mrs. Hudson, and a maid, Francis Webbe. This was not the end of it. On the voyage, it transpired that Miss Webbe was carrying an addition to the passenger list. From the Cape, the master of the New Year’s Gift informed the Directors of ‘a strange accident which hath happened contrary I think to any of your expectations’:

… and that is that one of the gentlewomen which came with Captain Towerson and his wife is great with child, and at this present is so big that I fear if she have not twins she will hardly hold out to Surat.

The Towersons, he wrote, had been as ignorant of her condition as anyone else,

… only it was Master Steele’s project at home to get them to entertain her, and so had thought it should have been kept secret till they had come to Suratt, but that her belly told tales and could no longer be hid under the name of a timpany.[39]

Richard Steele was an opportunist who, in 1611, had been sent by some Levant merchants into Persia, in pursuit of John Mildenhall, whom they suspected of stealing goods. Later, he established himself at Surat, as an expert on Persian trade. Upon his return to London, he urged the Company to support a scheme for constructing waterworks in Agra, for which they might supply the lead. They declined to participate, which was wise, but they permitted Steele to travel to India, with the Towersons, on Martin Pring’s Fifth Voyage.[40]

The Steeles were married at the Cape, ‘under a bush’, as Sir Thomas Roe put it. Henry Golding, chaplain of the Anne, officiated. Then, upon arrival at Surat, Mrs. Steele ‘travailed on shore, and brought forth, to the no small joy of her husband, a goodly young son.’ Edward Monox wrote to London, ‘you may hope one day to have as good service as from his father.’ In the meantime, however, he warned,

… you must be content to suffer want of due service from some whom would be glad to express their duty therein, which for want of convenient room they could not perform, the house being so pestered with them and Captain Towerson and their retinue…

Monox complained that he had ‘nether chamber to lie in or place to write in.’ Gabriel, he wrote, ‘could not or would not find a house in all the town; but I cannot greatly blame him, for it eased his purse well.’[41]

When, at Agra, Sir Thomas learned of this commandeering of Company property, he was not pleased. Money was ‘dear ware in India.’ Yet, to Thomas Kerridge, he declared the Towersons were welcome:

His hast to court wilbe convenient, for his wife may assist me to Normahal (Nur Jahan) better then all this court.[42]

Jahangir, for all that he was ‘Conqueror of the World’, was much in thrall to his twentieth consort. Her father, Ghyias Beg, was Itimad-ud-Daula (‘Pillar of State’), her brother, Asaf Khan, a major courtier, and her niece (Mumtaz Mahal, Asaf Khan’s daughter) the wife of Prince Khurram, the Emperor’s favourite son. Theirs was a formidable faction, seeking to advance Khurram’s interests against his elder brothers, Sultan Khusrau and Sultan Parwiz. Khurram had been allied to the Portuguese, which made the faction a focus of Roe’s attention.[43]

From the first, Roe mistrusted Steele. Reports from Surat were that he had ‘mistaken himself already, and given out which he is not.’ Soon, Roe received letters,

… wherein he makes himself chief and all, sent by His Majesty, without mention of me; whereas, to deal truly, he is sent only as a factor, and scarce that.

To clear the air, Roe arranged it that Steele should convey to Agra a large pearl, the most important of the voyage’s royal presents. (For security, it was hidden in the bored-out stock of a musket.) Steele arrived on 2 November, when Roe found him ‘high in his conceits.’ The delivery of the pearl was his saving grace. Roe made plain his opinion of the waterworks’ prospects, but he accepted that Steele ‘should make triall for satisfaction … and make proofe what conditions may be obtained.’ With respect to Steele’s wife, he was blunter. To his journal, he confided,

I dealt with him cleerely: she could not stay with our safety, nor his masters content: that he ruined his fortunes, if by amends hee repayred it not: that shee should not travel nor live on the Companies purse (I know the charge of women).

In this, Roe believes he had the best of the argument. He had also become more confident of Asaf Khan’s support. ‘[Towerson’s] wives helpe I neede not,’ he now decided. ‘Normahall is my solicitor, and her brother my broker.’ So, having ‘perswaded’ Steele, he wrote,

I likewise practised the discouragement of Captaine Towerson about his wife (you know not the danger, the trouble, the inconvenience of granting these liberties). To effect this, I perswaded Abraham, his father in law here, to hold fast: I wrote to them the gripings of this court, the small hope of reliefe from his alliance, who expected great matters from him.

To Kerridge, Roe wrote that he had prevailed with Steele ‘so far in as that his own reason hath drawn his consent.’ Still,

… this cannot be so well effected except you join with him to discourage Captain Towerson from purpose to stay. His father(-in-law) will do little, nor is able; his mother-in-law poor, at Agra, and he will be consumed if he fall to travel on his own purse, and from the King can expect nothing but penny for penny at best.

In respect of private trade, Roe professed himself shocked by what Steele had told him of Kerridge’s policy of ‘strictness’. He wrote that he hoped this meant Towerson would not enjoy ‘that libertie he expects.’ He was,

… furnished for above one thousand pound sterling, first penny here, and Steele at least two hundred pound, which he presumes sending home his wife, his credit and merit is so good towards you, that you will admit in this case, to be rid of such cattell.

‘I will not buy,’ Roe told Kerridge, ‘but order that it be marked and consigned to you, that you may measure your owne hand.’ Still, whilst he warned that Gabriel had brought much ‘trash’, he permitted Surat to trade such of his wares as might not yield a loss. Particular care, he suggested, should be taken over his ‘jewel’, in case it be ‘of the new rock.’ This was less valuable than the old. ‘If fair,’ he wrote, ‘will sell, but to no profit.’[44]

By 18 December, Roe’s mood had blackened. There was a rumour that Towerson intended to go ‘to the sowthward’ (ie. to Bantam). This Roe was extremely reluctant to permit. It provoked in him an outburst of anger:

He pretended to the Company no purpose but to come to Suratt, only to visit his wife’s friends, not to trade, but those things he had, pretended for gifts and presents, and to that end signed them a deed with his wife … With this they have given me caution to have an eye on his courses and actions, which were a very blind one if I should not see the disadvantage of his passing so great a stock through all the Company’s commodities and ports.

Roe’s letter puts into relief the Company’s earlier reasons for refusing Towerson a commission. But Sir Thomas was also concerned by the example he was setting:

Neither can I see how the Company can give such a liberty to him, and so restrain me and all their servants, whose deserts will equal any captain or woman. Perhaps they thought [Mrs. Towerson’s] greatness could do them some pleasure; if so they mistake their friends; it is well if she can return as she came.[45]

Unfortunately, even the best laid plans may go awry. When Towerson insisted on bringing his wife to Court, as central to his plans, Steele appealed to Roe’s better nature. His wife had ‘one child sucking and … [was] forward of a nother; it were unfitt to send her alone among men.’ She accompanied Mariam’s household.[46]

There was something about Mrs. Steele that stirred the animal spirits. Even Rev. Golding was susceptible to her charms. In March 1618, Martin Pring wrote that, when Steele was away, the preacher was permitted to keep her company. This he did for three to four months, a period marked by a sharp decline in Golding’s giving of sermons. When Mrs. Steele travelled to Ahmedabad, Golding was ‘straungely importunate’ to go with her. Permission was denied but, Pring writes,

For a daie or twoe he dissembled his intent, in which time hee fitted himselfe secretly with Moores apparell, which being procured and all thinges els fitt for a fugitive, hee takes leave of Mr. Kerridge, pretending to come aboard the Anne. Hee was no sooner over the river but hee altered his course, put on his Moores apparell, and took his way for Amadvar.

For all his slipperiness, however, Golding did not accomplish his intent. Pring asked Roe to speed him back to Surat ‘that hee may not disgrace our religion and country.’ The ambassador did so. ‘I gave consent for the best to Mrs. Steele,’ he wrote, ‘but never for the minister.’ He added, ‘now her husband discovers himselfe; but one of us must breake in this business.’[47]

There was more. Towerson was accompanied by the interloping captain Samuel Newse. He had been intercepted by Pring when on the point of robbing the Queen Mother’s junk. Jahangir had been told that Newse had been sent home to King James, to ‘make an example of such boldness to dare to disturb the allies of his crown.’ For Newse suddenly to turn up in Ahmedabad was highly embarrassing: he might have been recognised by one of the Begum’s merchants. Fortunately, he was amenable to reason, and he was secreted out of the country.[48]

Despite these provocations, Roe presented Towerson and Steele to the emperor. In theory, having a Persian speaker in his entourage should have been to the ambassador’s advantage. It was not so. ‘When he was my toong (tongue) to the Kyng,’ Roe complained, ‘[Steele] would deliver his owne tales and not a woord what I commanded.’ Before long, his workmen were on the emperor’s payroll. Steele, his wife, and ten servants, moved into an Ahmedabad mansion. The waterworks moved very slowly. Steele was interested in other things. Roe complained,

… hee layed his own plot well; for hee brought a paynter … [who]is bound to him for seven years (a very good woorkeman both in lymming and oyle) to devide profitts; him hee preferred to the King in his owne trade, pretended to mee for an engineer in water woorkes. His smith makes clocks; of all he shares the moyetie. I required to bynd them to yow by covenant … but his paynter would not, and when I offer to send him home, I dare not for the Kings displeasure …[49]

The Steeles later informed Purchas that, through the offices of this painter, Richard obtained access to the emperor’s harem (conveniently, a transparent cloth was placed over his head by the court eunuch). Mrs. Steele visited the home of the minister and poet, Abdur Rahim Khan-i-Khanan,

… where sate many women, slaves to Chan-Channas daughter, of divers Nations and complexions; some blacke, exceedingly lovely and comely of person notwithstanding, whose haire before did stand up with right tufts, as if it had growne upward, nor would ruffling disorder them; some browne, of Indian complexion: others very white, but pale, and not ruddy …[50]

Rightly, Roe expected Steele’s schemes to run out of road. For him, he had no sympathy, for the Towersons, rather more:

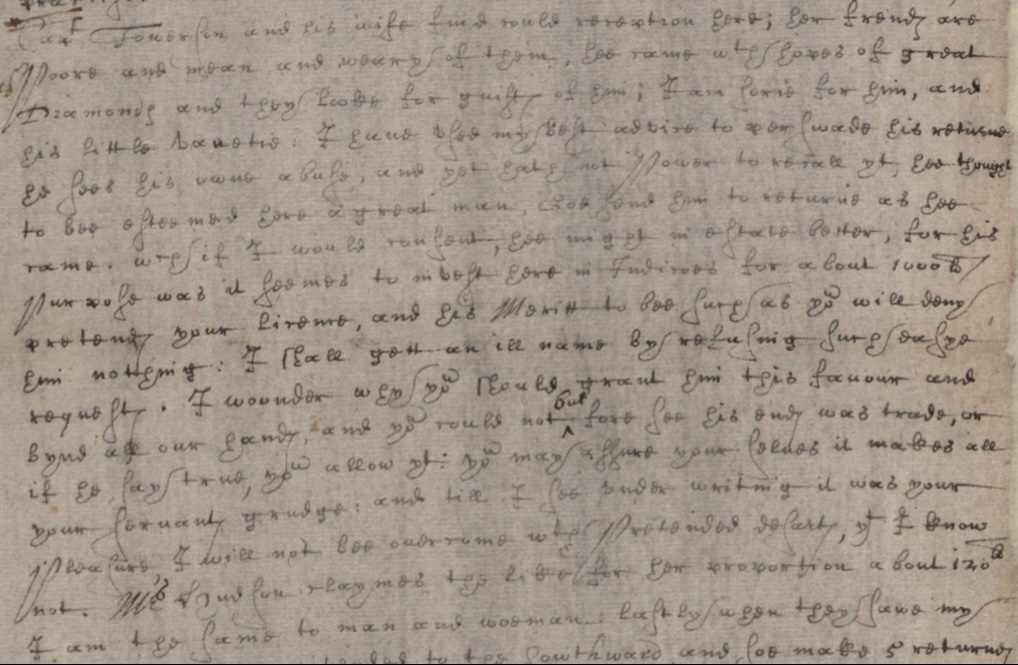

Captain Towerson and his wife find could reception here. Her frends are Poore and mean and weary of them. Hee came with hopes of great Diamonds, and they looke for guifts of him. I am sorie for him and his little vanetie. I have used my best advice to perswade his returne. He sees his owne abuse, and yet hath not Power to recall yt. Hee thought to bee esteemed here a great man; God send him to returne as hee came …

Roe criticised the Directors, for failing to see that Towerson’s purpose was trade, or for realising it, and allowing it. ‘Yow may assure yourselves it makes all your servants grudge,’ he wrote, ‘and till I see under writing it was your Pleasure I will not bee overcome with Pretended desarts that I know not.’

Towerson, he decided, was resolved to stay ‘perhaps till I am gone, to find an easier man’:

Hee may be deceived. I offered him to returne this yeare and, to ease us of his woemen, liberty to invest his stock in Cloth and other goods, Indico excepted, provided to bee consigned to you; but hee hath better hopes, and I assure you I feare hee will spend most of his stock and ease mee of refusing him of unreasonable demands … He hath many ends never to you propounded: but bee assured I will looke to him. You neede not doubt any displeasure hee can rayse you by her kindred, nor hope of any assistance. They fence one upon another and are both weary. The mony Mentioned of Captain Hawkings is fallen by misinformation from 2,000 rupees to 200…

The writing, then, was on the wall. Roe told Sir Thomas Smythe, ‘[Towerson] wilbe deceived in expectation of his friends,’ adding, for himself, ‘I know not what in these cases [to] doe.’ In the end, he took Gabriel with him to England, in February 1619. Faut de mieux, Steele and his family accompanied them.[51]

Mrs. Towerson chose to remain, apparently to her husband’s displeasure. However, whether William ever meant to re-join her is to be doubted. On Christmas Day, William Biddulph reported that she ‘hath spent all the meanes hir husband left with hir for hir expence, and is att present in debte to my knowledge two or three hundred ru[pees].’ She and her mother applied for loans pending Towerson’s return, but Biddulph was disinclined to be generous. In response, he wrote, ‘they rayled uppon hir husband and nation … which is noe smale discreeditt to our nation.’ He urged London to ‘take some course with hir husband for hir mayntaynnance, or send for hir to him to avoid expence, trouble and scandall.’ Nothing happened. The record of Mariam’s pleas and complaints continues until the end of 1621, when we are told she had ‘noe minde for England’. Then the trail goes cold.[52]

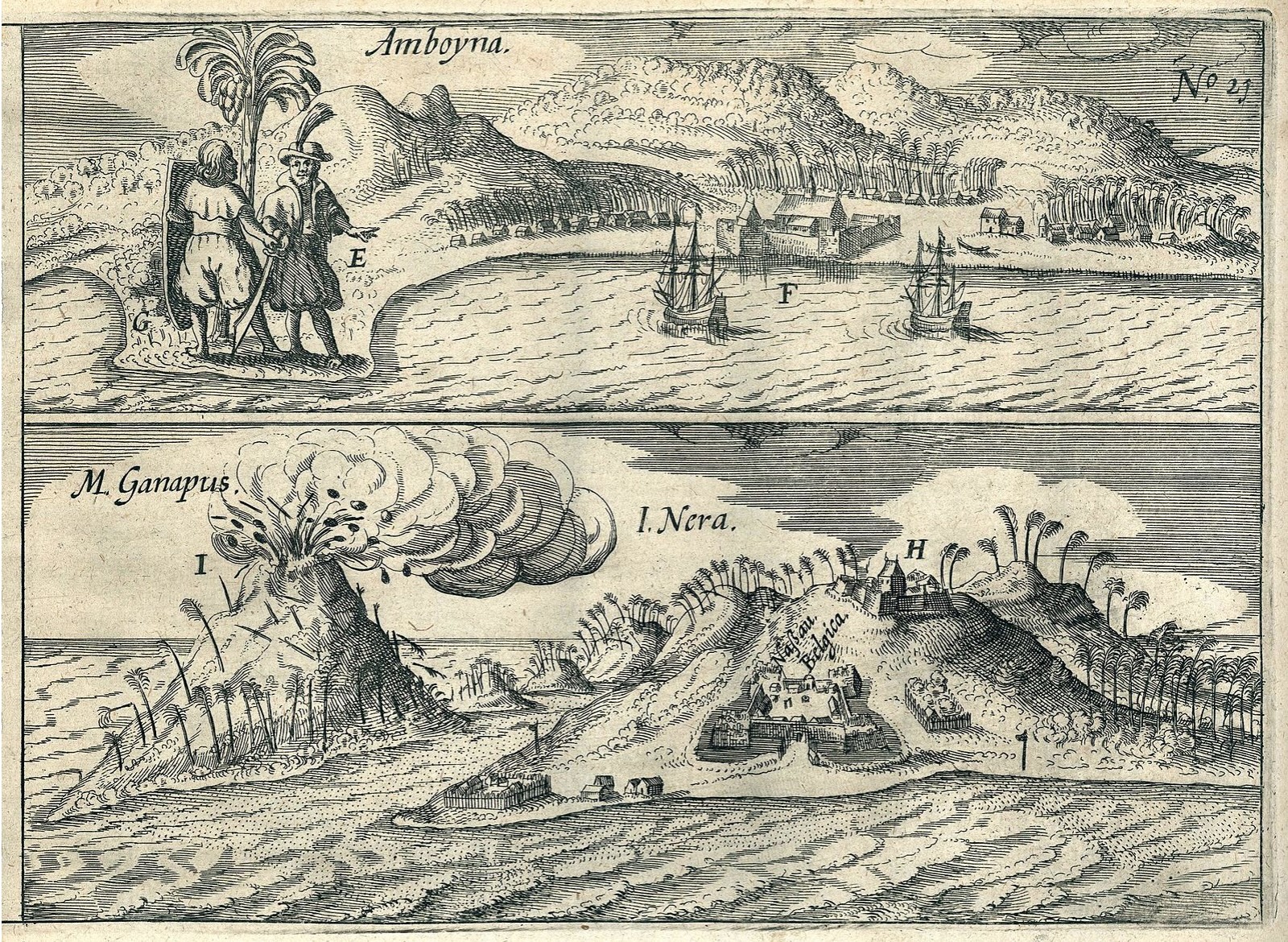

Back in the East Indies (1620-1623). The Amboyna Massacre

Towerson arrived at Plymouth, in the autumn of 1619. In early December, he applied for re-employment by the Company. Despite complaints about his private trade, the Directors appointed him principal factor in the Moluccas, on 24 January 1620. His salary was £10 per month. Gabriel hoped to command one of the ships in the outbound fleet, but this was refused. Instead, he sailed on the Anne. Quite when she departed is unclear: on her return from India, she had run aground near Gravesend, and for a while, it was feared she would be cut up and saved ‘by morsels’. We first hear of Towerson’s progress, on 30 May 1621, when it is recorded that,

… because of differences aboard the Lesser James between John Davis, pilot, and John Wood, master, ever since they left England, Capt. Gabriel Towerson is appointed commander of that ship until her arrival in Jacatra.

So, Gabriel got his command in the end. He reached Jakarta in November 1621, in the company of the Anne and ‘a rotten hulk for a victualler’.[53]

Much had changed since he had left Bantam, in 1608. Then, the competition had been fierce, but the English had not imagined that the Dutch meant to exclude them from the spice trade entirely. England had been Holland’s ally against Spain: a measure of market access would have been reasonable recompense for her assistance. That a monopoly was Holland’s objective became clear to London only when Dutch commissioners visited, in March 1613. They stood by the letter of their treaties with the natives. The English, they declared, were being extravagant if they expected to receive, free of cost, a share in the commerce which they had snatched from the Portuguese, at vast expense.[54]

In the Indies, relations were already hostile. Free traders like John Jourdain refused to limit their activities to islands, like Run and Wai, whose rulers had not signed treaties with Holland. To Jan Pieterszoon Coen, from 1613 the Dutch governor-general in the Indies, England’s dealings with Luhu and Kambelo, on Ceram, and with Hitu, on Amboyna, were inconsistent with even the meanest pretensions of neutrality. In April 1613, the two had a heated encounter at Luhu. Coen ‘in a chollericke manner’ complained of Jourdain’s purchases of cloves in places under Dutch protection. To the charge that he was no better than a thief, Jourdain responded that the Dutch,

.. had not onelie abused mee butt our whole nation, in disablinge us amonge the countrie people, threateninge them to burne their houses if they gave us any enterteynement, as alsoe in following us from place to place, persecutinge us, giveinge us a Judas kisse with faire words when behind our backes they sell us …[55]

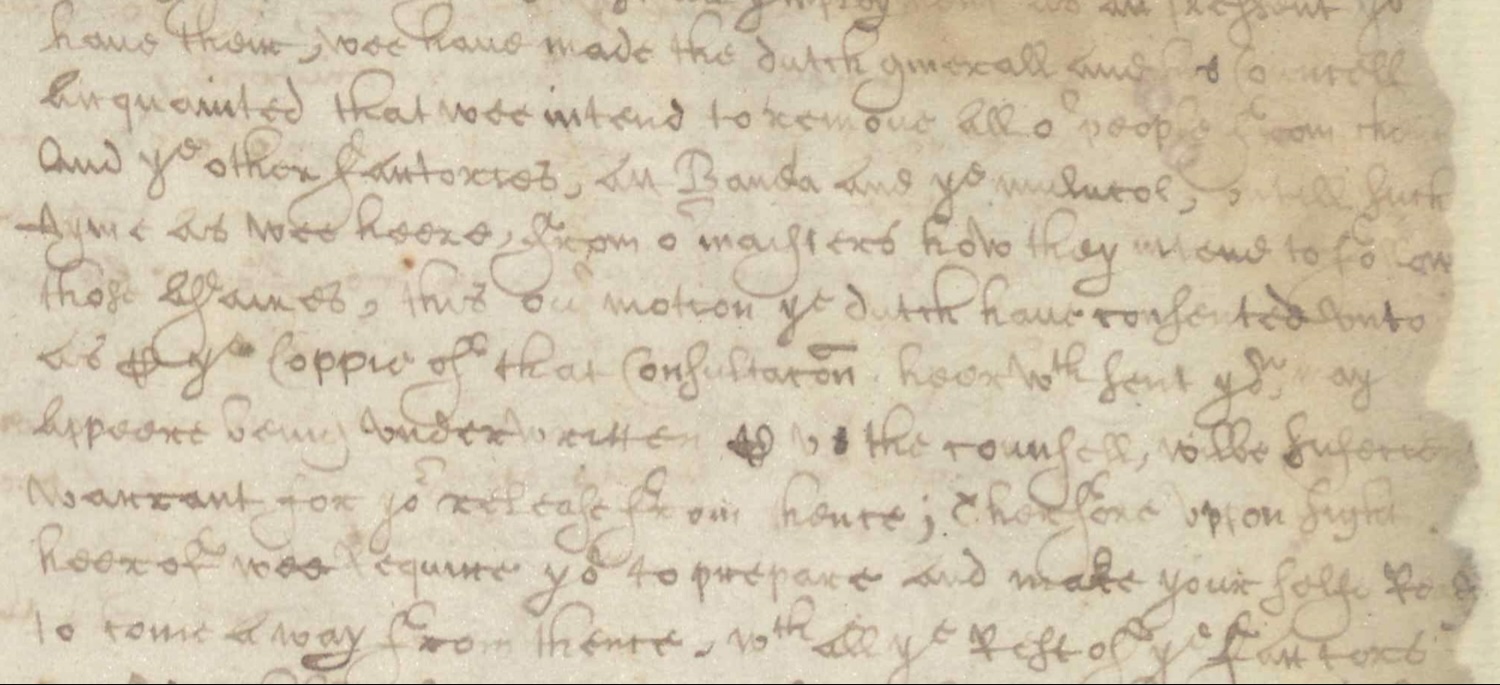

In 1616, Jourdain returned to London. He argued that a show of force would bring the Dutch to reason. In November 1617, the Directors accepted his opinion ‘that the Flemings either dare not or will not set upon the English.’ They sent a fleet under Sir Thomas Dale. But Jourdain had under-estimated Coen. There was an inconclusive naval battle, after which Dale failed in his attempt to seize the Dutch fort at Jakarta. He retired to the Coromandel coast for reinforcements, where he died. Before the fleet returned under Martin Pring, in April 1620, Coen had relieved Jakarta with reinforcements from Amboyna. Jourdain had been killed, with the loss of two ships, at Patani, and a further five ships had been lost off Sumatra, and in the Sunda Straits. In total, the Dutch captured eleven ships, most of them laden, for the loss of one. In October, even Nathaniel Courthope’s heroic defence of Pulo Run came to an end.[56]

Upon his arrival in Java, Pring was informed that a ‘Treaty of Defence’ had been signed in Europe between England and Holland. He was instructed to form a commercial and defensive union with the Dutch. Coen saw this as defeat snatched from the jaws of victory: worse, the treaty provided a screen for the English ‘serpent’ to use when striking at Dutch interests, surreptitiously, in partnership with native rebels. Certainly, on the face of it, the treaty suited the Company. Guaranteed a share in the spice trade, they moved their headquarters from Bantam to Batavia (as Jakarta was now called). They opened factories alongside the Dutch in Amboyna, Ternate, and Banda Neira. As a quid pro quo, however, they agreed to bear a third of the cost of the Dutch garrisons. This the Dutch deliberately inflated, knowing that the Company’s capital was short. They also involved the English in wars against people with whom they had no quarrel. Quickly, the factors became disconsolate. In July 1620, they wrote that their costs in the Moluccas and Bandas ran to £60,000 a year, chiefly because of wars against the Portuguese:

From Ternate and Tidore, places of great charge, come no cloves at all, the Dutch not daring to look over the walls of their forts at Tidore, yet keep the same to prevent the Spaniard from fortifying there. In time of peace the Ternatans are so beset with the Spanish forces and Tidoreses, their mortal enemies, that the cloves rot in the ground for want of people to gather them. Motir yields a very small quantity. Machian only two hundred baharrs per annum; Bachian, for want of people, not above forty baharrs yearly, but Amboyna and the factories adjoining Ceram yield upwards of 1,000 baharrs, and are places of the least charge, and greatest benefit in putting off our goods …[57]

Indubitably, lack of resources impelled the English to breach the letter of their obligations. Equally, London overestimated the resources available to their Batavian council. They assumed that Coen would make restitution for the ships he had seized, and he did nothing of the sort. In November 1621, the council were challenged by the Dutch to explain their failure to fulfil their pledges. In response, they minuted that,

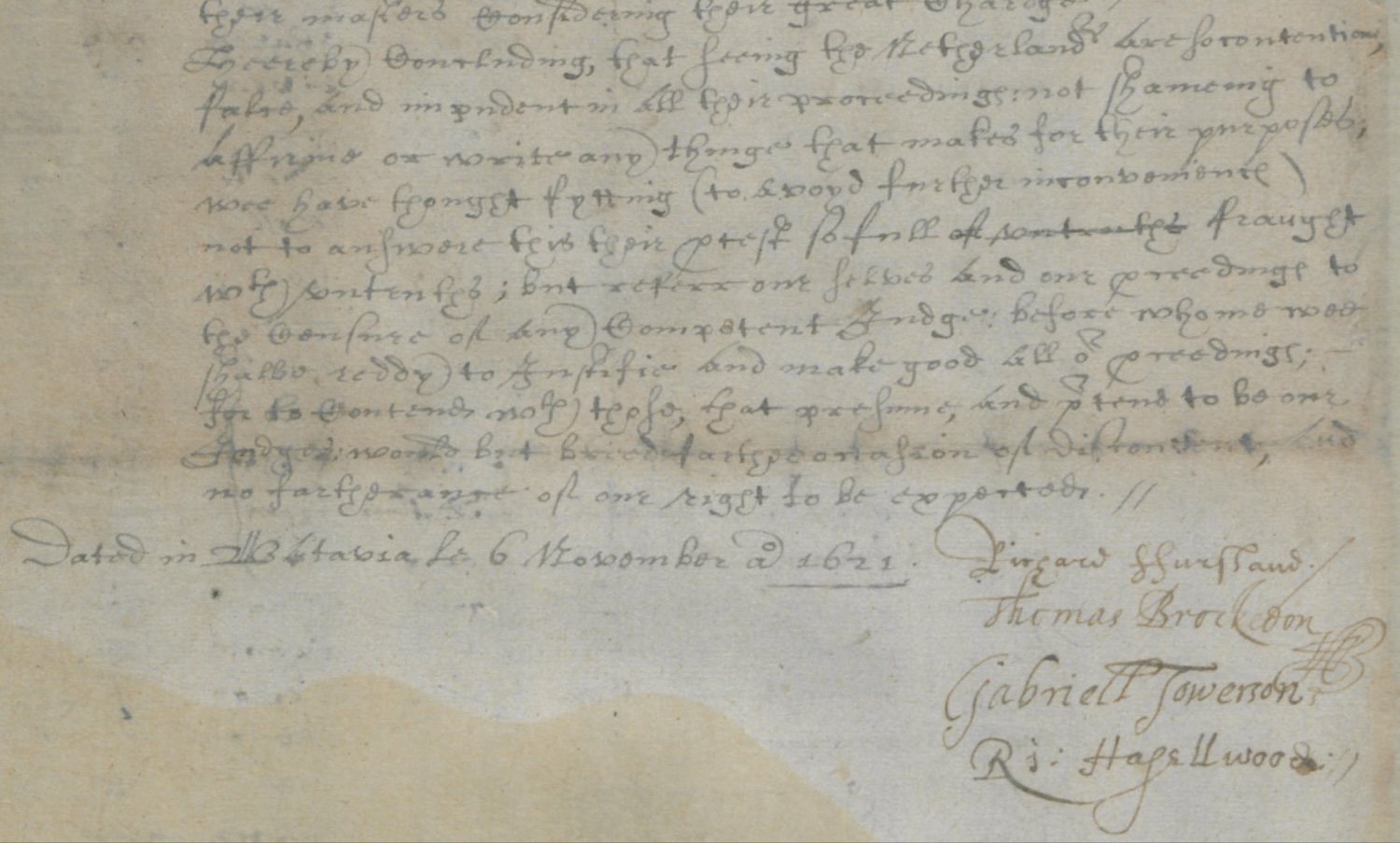

… seeing the Netherlanders are so contentious, false, and impudent in all their proceedings, not shaming to affirm or write anything that makes for their purposes, the undersigned have thought fit not to answer this their protest so fraught with untruths, but refer themselves and their proceedings to the censure of any competent judge, before whom they are ready to justify all their proceedings.[58]

Towerson was one of those who signed the document.

In December, they informed London that it was,

…needfull to agree with the Hollanders about the charge they demand for maintaining war with Bantam, otherwise they will lay what tax they please upon the English and hinder them buying pepper.

In fact, they reported, the pangeran wished to make peace, and the more sensible course was to send a ship or two, as there was pepper enough to lade ten vessels of eight hundred tons.[59]

On 11 January 1622, even as they characterised their experience of living with the Dutch as ‘a kind of slavery,’ the council appointed Towerson as their agent in Amboyna. (He replaced George Muschamp, who lost a leg to a cannonball at Patani, and was retiring ‘because of his disability of body.’) The council noted that ‘the Company’s factories must suffer much prejudice until they can be supplied with more able factors,’ which we may take as a compliment.[60]

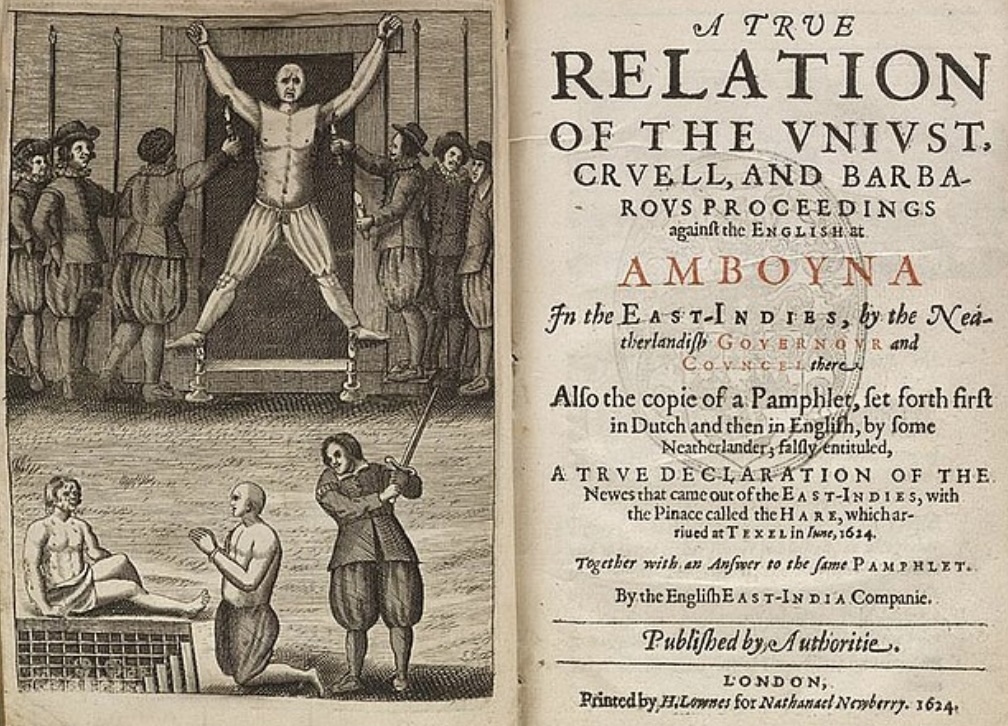

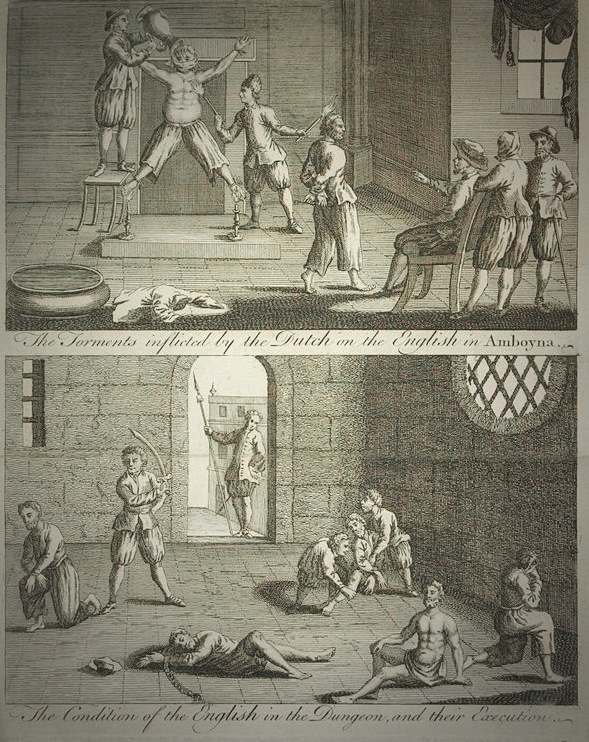

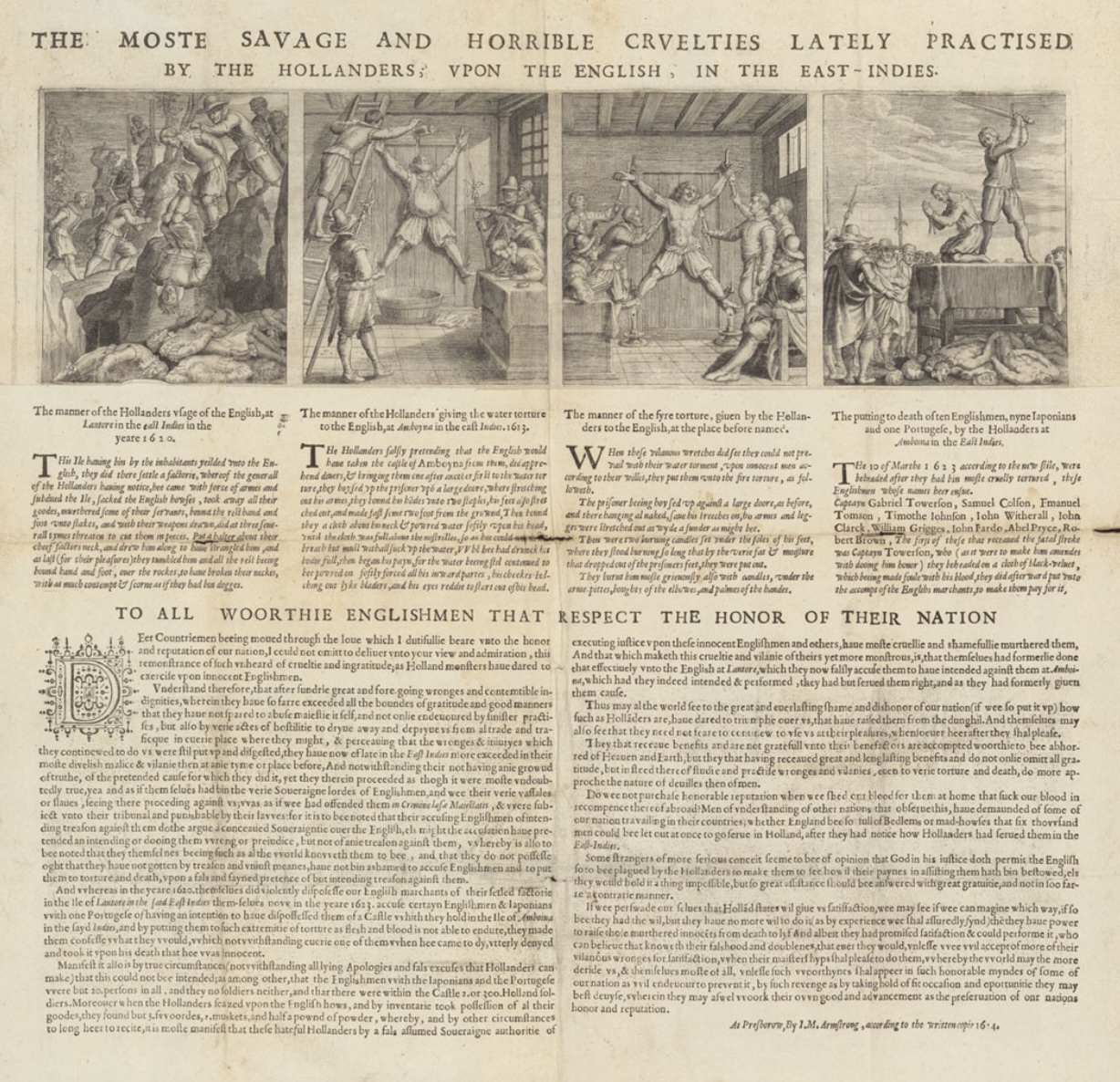

Then, on 27 February 1623, they learned that Towerson and nine of his colleagues had been executed for plotting to overthrow the Dutch garrison. The news of what came to be known as the ‘Amboyna Massacre’ caused a sensation when it reached England, in 1624. In a letter to Sir Dudley Carleton, Ambassador at the Hague, Abraham Chamberlain wrote,

The case is much commiserated by all sorts of people who cry out for revenge. The King takes it so to heart that he speaks somewhat exuberantly; [I] could wish he would say less so he would do more. For my part I shot my bolt at first, that if there were no wiser than I, we should stay or arrest the first [Dutch] Indian ship that comes in our way, and hang up upon Dover cliffs as many as we should find faulty or actors in this business, and then dispute the matter afterwards; for there is no other course to be held with such manner of men, as neither regard law nor justice, nor any other respect of equity or humanity, but only make gain their God.[61]

That Herman van Speult, the Dutch governor at Amboyna, believed in a plot is quite possible. After their bloody invasion of the Bandas, in 1621, the Dutch knew the natives were hostile. Apparently, they thought the English capable of siding with them. Indeed, in April 1621, Humphrey Fitzherbert had declared his desire to dislodge the Dutch in Amboyna. He said that, if others joined him, he would attempt ‘the surprizall thereof.’ In March 1622, a Bandanese conspiracy to hand Batavia over to the Javanese was uncovered. Richard Fursland, president of the council, wrote that the Dutch used torture to get the conspirators to incriminate the English, which demonstrated ‘in what danger we live being under their authority.’ In August, the same month in which a plot in Ceram was uncovered, Thomas Brockeden wrote that English members of the watch at Batavia were arrested, imprisoned, and threatened with torture ‘that they might make confessions against the President.’[62]

In December, Coen wrote to Martin Sonck, the Bandas governor, telling him not to trust even the natives’ wives and children: ‘They would turn Christian to act their parts the better.’ If any renegades were caught, they were to be executed, or sent out of his jurisdiction, to Batavia. The English, he warned, were to be trusted ‘no more than a public enemy ought to be trusted.’ If a conspiracy came to light, they should be punished without favour. He added that they should be permitted ‘no more slaves nor people than such as can no ways be any hindrance unto us.’ As if in anticipation, van Speult had written to Coen the previous June, promising that ‘our sovereignty shall not be diminished or injured in any way by [English] activities.’ If any were caught plotting, he declared, ‘we shall with your sanction do justice to them without delay.’[63]

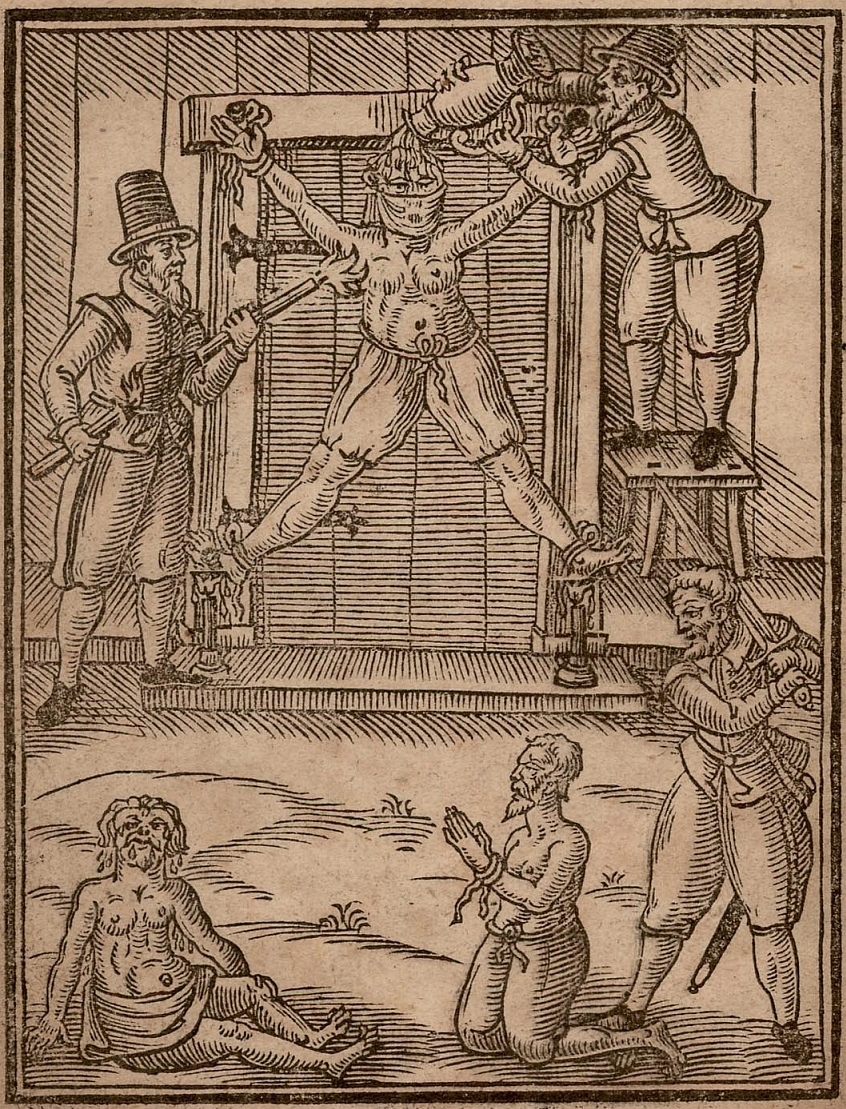

All of which suggests that the Dutchmen inside Amboyna’s Fort Victoria felt insecure. That Towerson should have schemed to seize it, and kill van Speult, is less likely. There were just twenty or so Englishmen in Amboyna and Ceram, and, according to their own sources, over four hundred Dutch. Towerson was said to have conspired with Japanese mercenaries on the island, but this force will have had to be substantial to improve the odds significantly. The Relation of 1624 says that there were ‘not thirty in all.’ The English might have been supported by the slave population, of 150 to two hundred, yet, even if Towerson’s force had captured the fort, they would have had to hold it: alongside their men on Amboyna, the Dutch had 463 in the Moluccas and 420 in the Bandas.[64]