The First British Contact with Korea (1613-1618)

The first English effort at trade actually pre-dated Hamel. It was the initiative of John Saris, captain of the Company’s voyage to Japan, in 1613. In a letter he wrote from Hirado, on 30 November, Richard Cocks, whom Saris had appointed head-merchant at the Company’s factory, mentioned that, in a small way, the Dutch had extended their tentacles of trade …

… into Corea per way of an iland called Tushma (Tsushima), wh’ch standeth w’thin sight of Corea & is a frend to the Emperor of Japan.

The opportunity obviously struck Saris as an interesting one as, in a letter he addressed to the Directors, on his return to Plymouth, he wrote,

I make noe doubt but your seruant Edward Sares is by this tyme in Corea, for from Tuschina I appoynted him to goe thither, beinge incouradged by the Chineses that our broad cloth was in greater request ther then hear. It is but 50 leagues ouer from Iapann, and from Tuschina much less.[2]

Sayers took with him a little less than eight hundred taels of product, three to four per cent of Japan factory’s stock. It did not take long for the holes in the Chinese argument to become apparent. On 9 March 1614, Richard Cocks wrote to Richard Wickham at Edo, reporting,

Yisterday I receaved a lettr from Tushma from Ed. Sayer dated 22th ultimo. He writes that he hath sould but for 31 taies of cloth of Cambaia w’th 5 piculls of pep’, and that the kynge & another man will take som 24 yardes of broadcloth, as he thinketh. He is out of hope of any good to be doone there, or Corea, and very desyrouse to goe from thence for Focaty (Fukuoka), per meanes of the p’swations of a greate m’rch’nt of that place, whoe is now at Tushma.

Although, in January 1615, William Eaton was sent with another, smaller cargo, comprising mostly pepper, Cocks quickly concluded that Tsushima was in no real position to open doors to Korea. On 25 November 1614, he wrote to London, informing them,

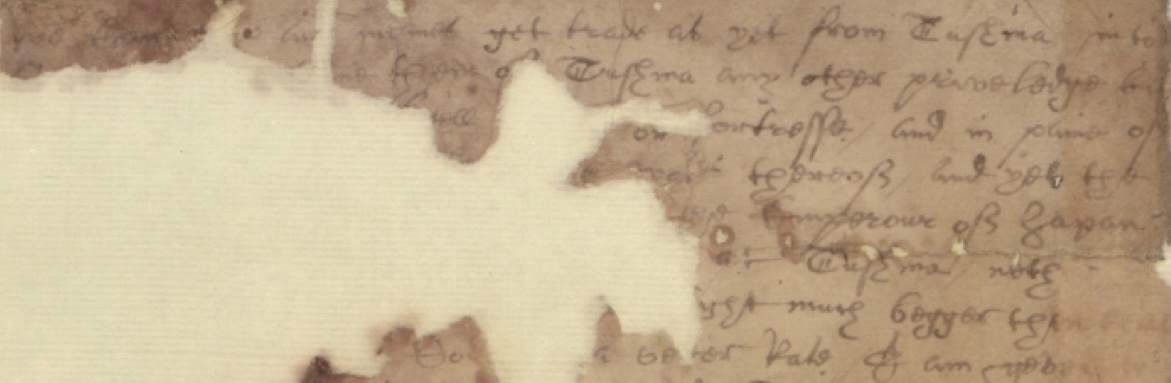

We cannot per any meanes get trade as yet from Tushma into Corea, [nether] have them of Tushma any other privelege but [to enter into one] littell towne or fortresse (Busan), and in paine of [death not to goe] w’thout the walles thereof to the landward; and yet the [king of Tushma is no] subject to the Emperour of Japan. [We could vent nothinge] but pepper at Tushma, nether no ]great quantity o]f that …

He then suggested that the Koreans had a most unusual approach to haulage:

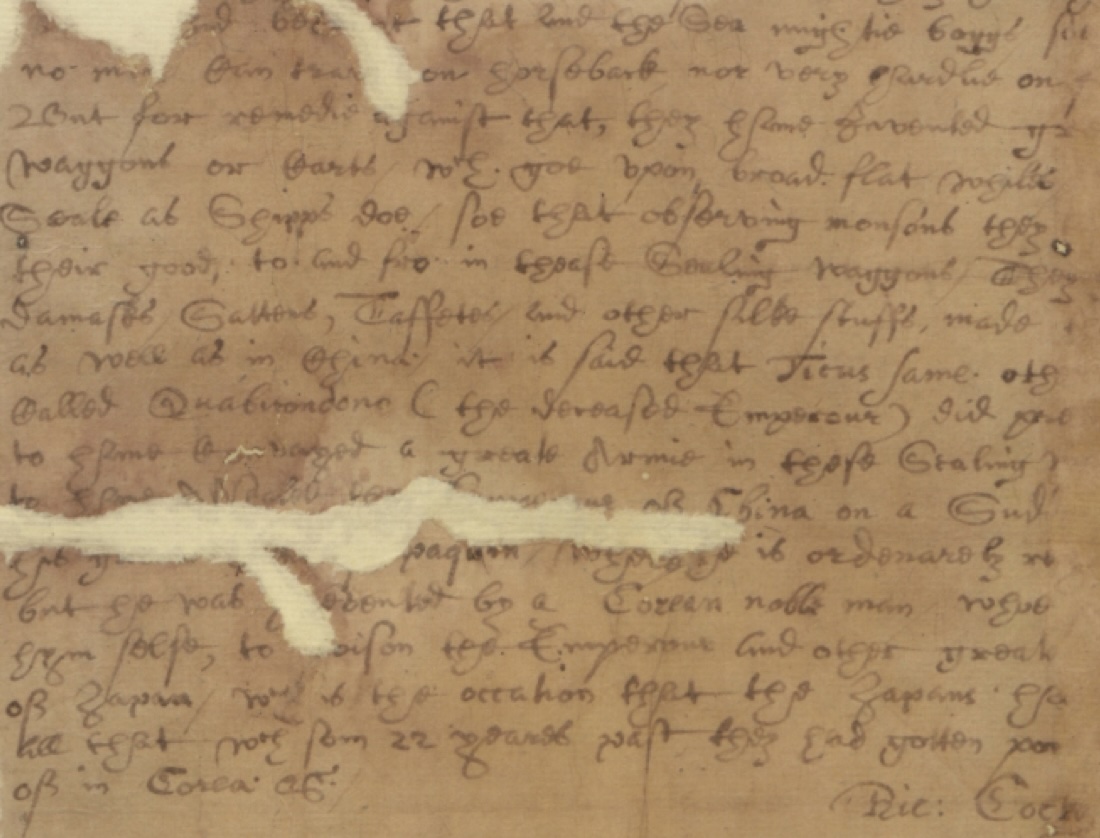

I am geven to understand that up in the contrey of Corea they have great citties, and betwixt that and the sea mightie boggs, soe that no man can travell on horseback nor very hardlie on foote. But, for remedie against that, they have invented greate waggons or carts w’ch goe upon broad flat whiles (wheels) under seale (sail), as shipps doe. Soe that, observing monsoons, they transport their goodes to and from in thease sealing waggons … It is said that Ticus Same, otherwais called Quabicon Dono (the deceased Emperour), did pretend to have convayed a greate armie in thease sealing waggons to have assealed the Emperour of China on a sudden in his greate cittie of Paquin (Peking), where he is ordenarely resident. But he was prevented by a Corean nobleman, whoe poisoned hymselfe to pison the Emperour and other greate men of Japan, w’ch is the occation that the Japans have lost all that wh’ch som 22 yeares past they had gotten pocession of in Corea, &c.[3]

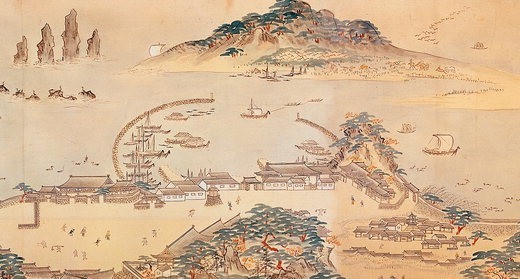

From where Cocks obtained his conception of these remarkable waggons, it is hard to say. He was no more correct to suggest that the So rulers of Tsushima were independent of Japan. Unquestionably, they carved space for themselves by playing a double game when dealing with the kingdoms between which their island was sandwiched. Even so, in 1603, So Yoshitoshi had been confirmed as the daimyo, or feudal lord of Tsushima, by Ieyasu, founder of the Tokugawa shogunate. Before the Imjin War between Japan and Korea (1592-1598), he had been sent by Toyotomi Hideyoshi (Cocks’s ‘Tico Same’) to obtain Seoul’s submission. In 1592, he led the Japanese assault on Busan and, in the second invasion of Korea, in 1597, he was a commander in the army of the left. After the war, the So remained the conduit for diplomacy between Korea and Japan, but the Koreans were under no illusion as to whom they owed their loyalty. Seoul had learned that they needed relations, of a sort, with the Japanese, but they were determined to keep the So on a tight leash. The men from Tsushima were given access to a single entrepôt on the south coast, which restricted their ability to gather intelligence. On land, they were confined to a walled compound on the outskirts of Busan.

The Koreans were permitted, occasionally, to send goodwill embassies to Japan. These they used to learn something of Japan’s intentions, as well as to obtain repatriations of Korean captives. The Japanese portrayed them as tribute missions. In 1618, Cocks encountered one such embassy during a visit to Edo. He wrote that the ambassadors had been well entertained along the way from Hirado. At the shogun’s court, they dined at his own table, ‘they being served by all the tonos (or kings) of Japon, every one having a head attire of a redish culler with a littell mark of silver lyke a fether in it.’ He was unsure of their purpose, however, writing,

Som report (and are the commons) that they are com to render obaysance and pay tribute, otherwaies themperour would have made wars against them againe. But others are of a contrary opinion, that they com to entreate the Emperour that them of Tushma may trade noe more into Corea, but rather that the Coreans may com to Tushma or other partes of Japon.

Later, Cocks indicated that they had come to visit the tomb of the deceased Japanese emperor, to congratulate his successor on his bloodless accession to the throne, and ‘to desire his Majestie to have the Coreans under his protection as his father had before hym, and to defend them against forraine envations.’ The last the Koreans would certainly not have condoned. As interpreters, it suited the So to construe Korean intentions to suit Japanese expectations, but at no stage would Korea have been comfortable conceding subservience to Japan, least of all after the war had concluded.

Cocks ended his report with the remark that he tried to speak with the ambassadors but could not, ‘per meanes of the King of Tushma, he being gelouse we might get trade into Corea, which non other are permitted but the Tushmeans.’ In fact, not only had the So no desire to open the trade to others, the Koreans had no wish to admit anyone from Japan except the So. The situation persisted until the early nineteenth century, when diplomatic exchanges between the two countries ended completely, and trade through Tsushima fell away.[4]

Cocks’ initiative, therefore, quickly withered, although later (in January 1617), he sent London a sample of a plant he had encountered, the health benefits of which were accepted far and wide:

I receved a box by the Adviz w’th a certen roote in it, w’ch came fro’ Cape Bona Speranza, but it proveth here worth nothing, it being dried that no substance remeaneth in it. Herew’thall, I send your Wor’s. som of it, w’th another peece of that wh’ch is good and cometh out of Corea. It is heare worth the wight in silver, but very littell to be had in comune men’s hands for that all is taken up for the Emperour by the kyng of Tushma, whome only hath lycense to trade w’th the Coreans, & all the tribute he payeth to the Emperour is of this rowte. Yt is helde heare for the most pretious thing for phisick that is in the world and (as they thinke) is suffitient to put lyfe into any man, yf he can but draw breath. Yet must be used in measure, or else it is hurtfull.[5]

Since it was impossible to obtain ginseng in any quantity, that was the limit of the East India Company’s engagement with Korea.

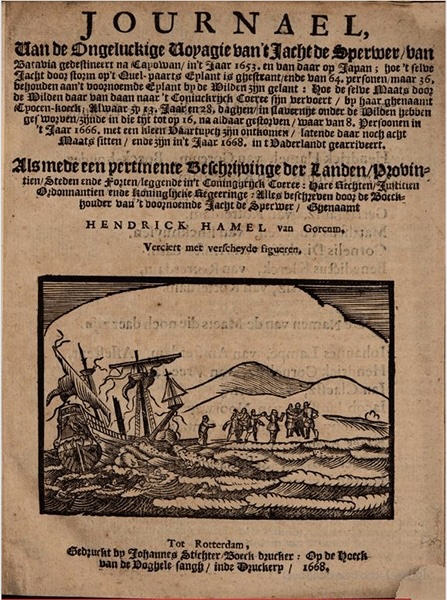

What might the experience of Hamel have led the British to expect later? In truth, his encounter had been an unhappy one. He reached Korea as a result of a shipwreck, in 1653, and the Koreans were most unwilling to let him leave. Eventually, he and seven others persuaded a fisherman to sell them a boat. In this they escaped to Nagasaki, which they reached in September 1667, thirteen years after they had been washed up on the southern isle of Jeju.

Unsurprisingly, Hamel’s picture of Korea is not of a land of milk and honey. The winters were uniformly harsh, the treatment by the Koreans occasionally less so. In 1665, Hamel summarised his experience, writing,

Our comrades in the other two towns had, with the coming and going of their commandants, some easy times and some hard times, because their commandants were like ours, some good and some angry. But we all had to put up with this, realising that we were poor prisoners in a heathen country, thanking God that they kept us alive and that they gave us enough food so that we would not die of hunger.

The three years to 1663 were a period of famine, in which thousands died. Guards were deployed on the roads against highwaymen, to bury the dead and to protect the warehouses against looting, which was often perpetrated by ‘the slaves of important people.’ To survive, the people resorted to the consumption of acorns and the bark of pine trees.

Korea was under pressure from Peking, and had suffered from the invasion of the Japanese, but Hamel never makes explicit why he was detained. Another Dutchman, Jan Weltevree, captive since 1627, had been simply told by the king,

If you were a bird, you could freely fly [to Japan]. We do not send strangers away from our country. We will take care of you, giving you board and clothing, and thus you will finish your life in this country.

In his account, Hamel himself reports that,

Before the Tartar seized control of Korea this was a country of abundance and playfulness. People did nothing but eat, drink and be merry. But now they have suffered so much from the Tartars and the Japanese that in bad years they hardly have enough to keep going, because of the heavy tributes they have to provide, mainly to the Tartar, who comes three times a year to collect these.

As he embarks on his account of their final escape, Hamel explains that he and his companions decided to try their chance rather than ‘constantly live in sorrow, sadness and in slavery in this heathen nation, brought on us every day by a crowd of spiteful people.’

After his arrival at Batavia, the Dutch briefly considered opening relations before deciding that,

… [as long] as we have in Japan our residence and trade, we should forget about the idea of doing any trade in Korea, in order not to rouse any jealousy or mistrust in the Japanese, not to mention the fact that the Chinese would not tolerate us being there.

At a minimum, then, the impression is of a country with modest resources, and less desire to engage with the world. Englishmen with long memories might not have recalled how unsuccessful Cocks had been, but Hamel’s descriptions provided little incentive to mount further expeditions to Korea.[6]

The Visit of James Colnett (1791)

In 1791, however, James Colnett briefly passed by Korea, hoping to sell some otter pelts. These had been refused at Canton, so it was an opportunistic move. Even so, Colnett left Macao in optimistic mood, expressing the opinion that,

… all Nations improve by commerce which I have every reason to believe will soon be extended to Corea and Japon where a great Call for furs will happen.

He was greatly disappointed. In his ship Argonaut, he stopped first at Cocks’s Tsushima, where he sent a boat towards the shore,

… which the Guard Boats prevented, nor would they give [those on board] any Information, or hold any intercourse, but … called out Curre-Curre, at the same time making signs for them to depart … Threat’ning by signs if they attempted to Land, or if they and Vessel did not go away would cut our heads off.

Colnett delayed until the following morning, in the hope the islanders’ attitude might change. It did not, but, having met with disappointment in Japan also, he returned to the Korean mainland, anchoring near Busan, on 25 August.

At first, his reception was surprisingly friendly:

The Natives receiv’d me with open Arms, without the smallest dread or apprehension, coming on board without the smallest hesitation, shewing me a point of Land, which they assured me was a harbour, desiring me to hand my sails, and give them my Tow rope.

Soon, Colnett was put on his guard by the officious behaviour of the Koreans and by the apparent absence of an inlet in the direction in which they were pointing. His suspicions were increased further by the signals being made to the shore, and by the numbers that were gathering there. In the bustle, the Koreans seemed to be barricading their houses with bushes. Then, he says,

At one time observing them Quick in making signals to each other and altho’ I had just sounded in 29 fathoms, I order’d the hand lead to be hove, when to my Surprise found myself in 3 fathoms, on the Top of a Rock. I haul’d off with the greatest precipitation which greatly surprised them, for they did not observe the man in the Chains, he being on the Opposite side. They then attempted to take the Helm from the 2nd mate.

Even so, Colnett hoped that everything was meant well and that there had simply been a misunderstanding resulting from the Koreans’ anxiety about getting the Argonaut into port. He arranged for a gunner and a line to be transferred into one of the Korean boats to sound the way. In this, one might have thought, he was demonstrating a surprising degree of insouciance:

For that purpose we stood on a little further, when my suspicions increas’d; before this the Boats far outsailed me with the sail I was carrying, and till this kept constantly ahead, now they had my man in Lagg’d aStern. I order’d the man at the helm to steer more off the Land, on which they were going to seize the helm from him by force, but being oppos’d order’d a boat along side, that my man was not in, which I conjectured was to assist them to make their escape, and take my man with them.

Colnett attempted to hold some of the Koreans on the Argonaut hostage, but they escaped his crew’s clutches and jumped overboard. Colnett promptly brought some of his weaponry into view. And, by making it clear what would happen if his man was not returned to his ship, he eventually succeeded in recovering him. The Korean boats then pulled away and Colnett anchored.

At 4 o’clock, however,

… they came off again, I believe to attack us, but it blew very fresh, which I think prevented them; but one boat coming nearer than the rest and threatening to beat our brains out with a Club – I order’d a musquet to be fired over them, but my orders were Exceeded whether intentionally I cannot say, and the boat was fired thro’, and I am apprehensive one man wounded. This alarm’d them full as much as ever I saw Indians in my life, and they all left me. I weighed and stood on the Northward.

The following evening, there was a storm. The Argonaut narrowly escaped being dashed against a huge perpendicular rock. Then the heavy sea struck the rudder, broke two of its gudgeons, unshipped it, and broke it in two. Colnett decided his attempt ‘was intirely done with.’ He wasn’t greatly sorry, as,

… to seek a Port among such unhospitable people I look’d on as a forlorn hope, giving myself and Vessel up a prey to people little better than Savages …

He made for Chusan, an island a little to the south of Shanghai. There he drew his conclusions that,

Both the Japanese and Coreans, Chinamen-like, from national prejudices and custom, always behave Obsequious to those they think superior to them, and Tyrannical to those they have the smallest idea are their inferiors.

He remained of the view that his furs would find a good market in both countries, and that the region, even the southern part of Korea, was blessed with good harbours, but he advised that the trade was too hazardous to be undertaken without ‘an exclusive privilege … granted by charter’ (which would have suited his sponsors) and that ‘whatever Chance there may be of carrying on a Trade on the South Coast, you must always be under Arms.’[7]

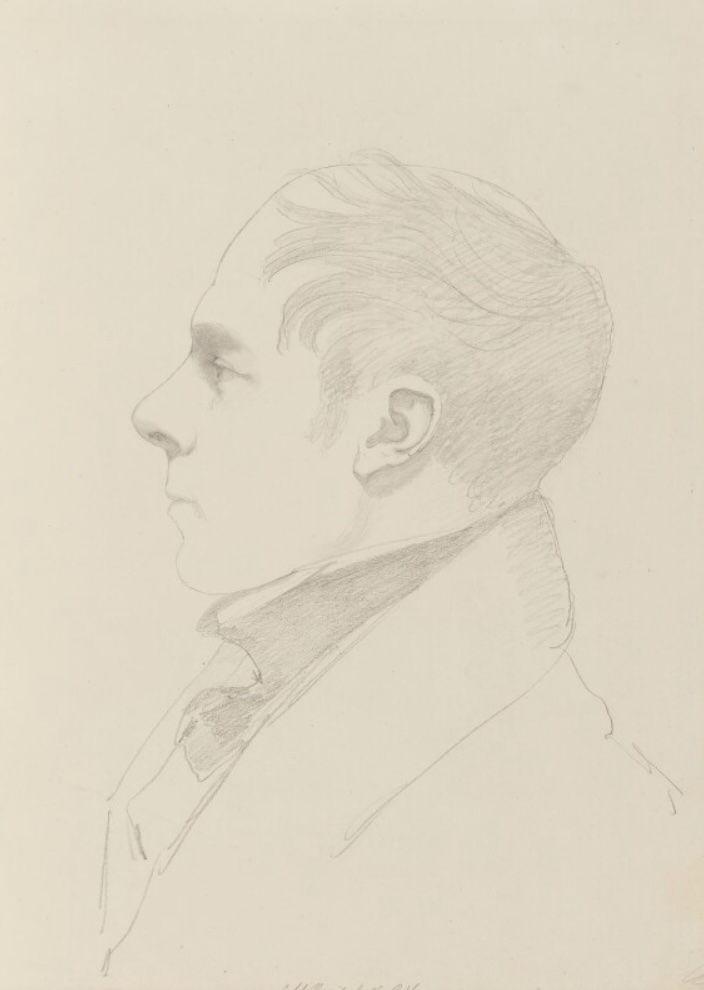

The Expedition of William Broughton (1797)

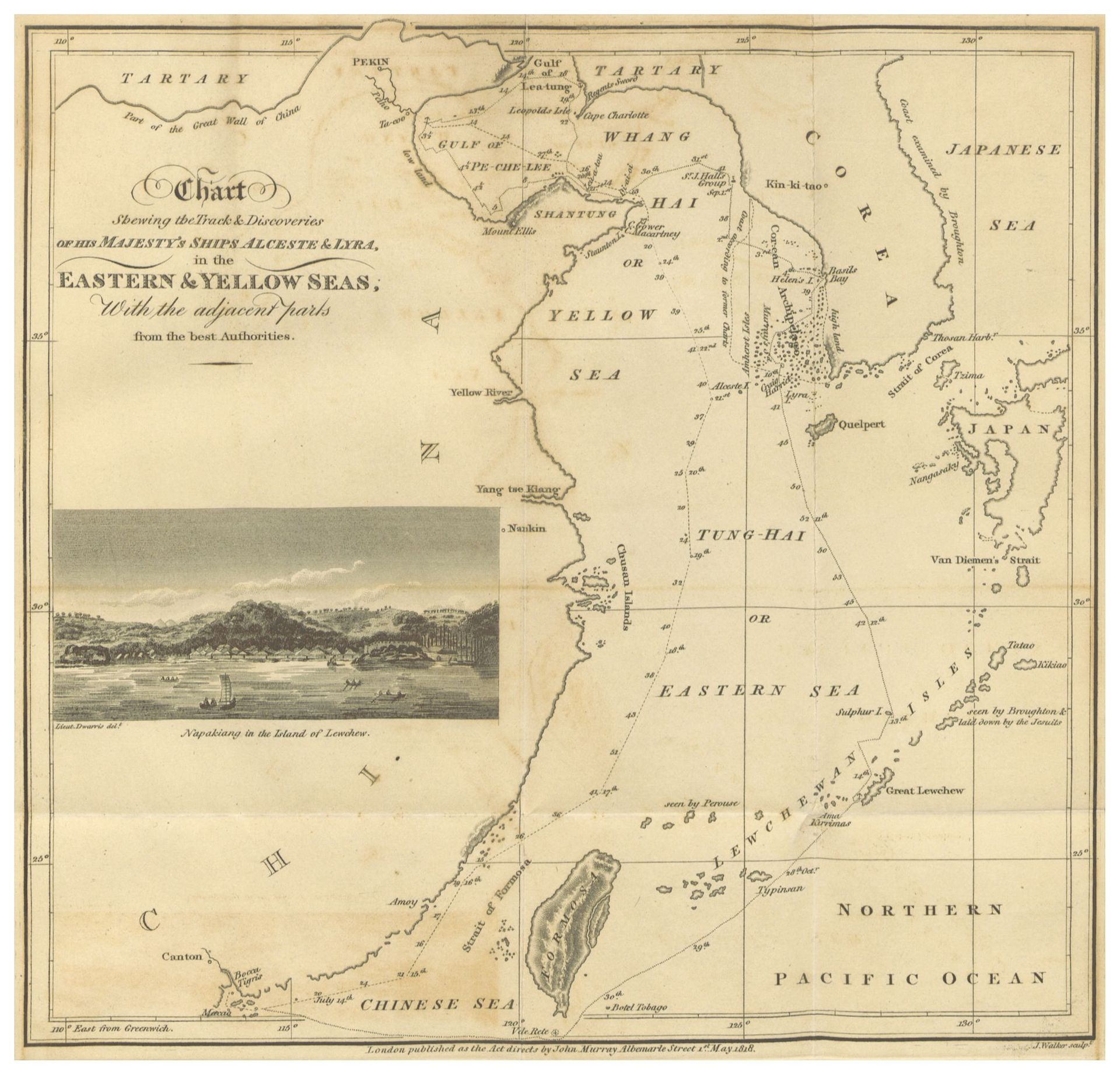

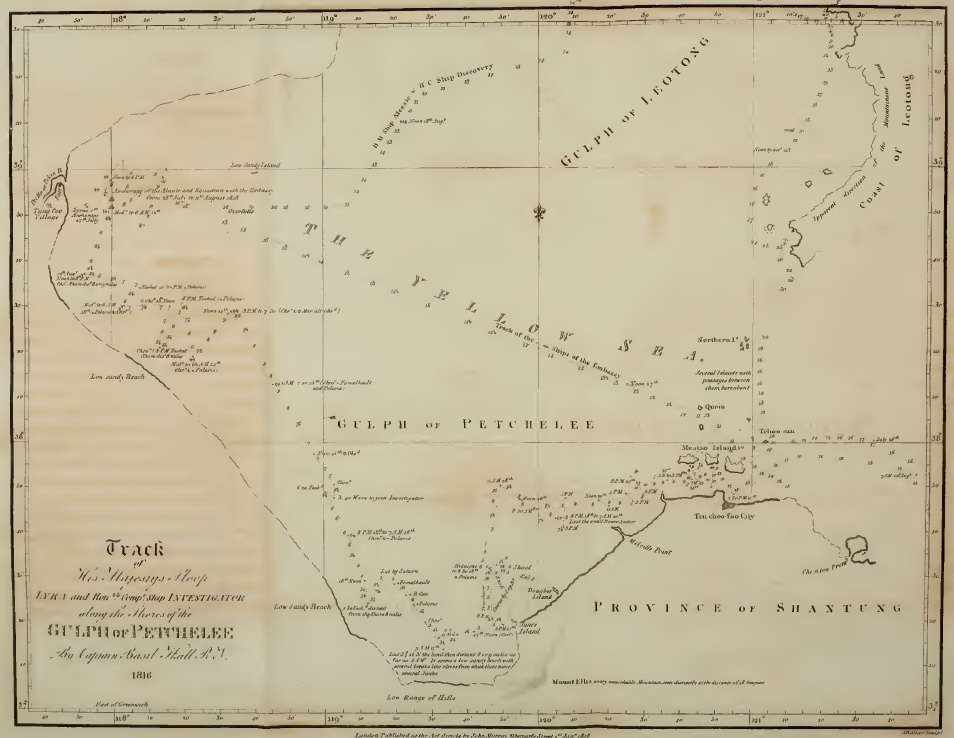

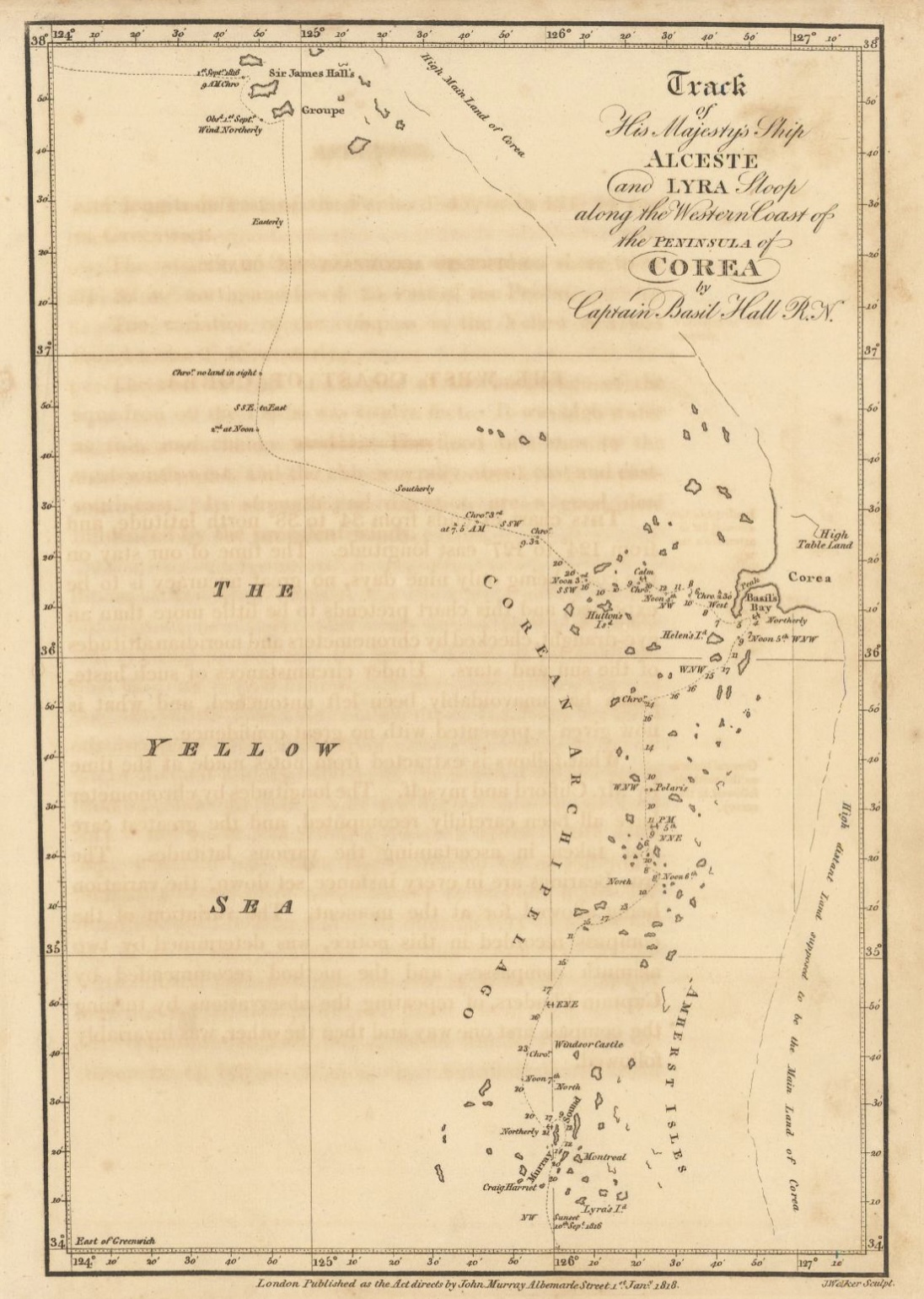

One would have thought that, with this, Britain might have passed over Korea, in quest of opportunities elsewhere. Yet, a chart of the track of the Alceste and the Lyra, in surgeon John Mcleod’s account of the expedition of 1816, reveals that it was not, in fact, Britain’s first. The eastern coast of the peninsular, it transpires, had previously been ‘examined by Broughton.’ The reference is to Captain William Broughton, who published a narrative of his voyage to the North Pacific (1795-98), in 1804.

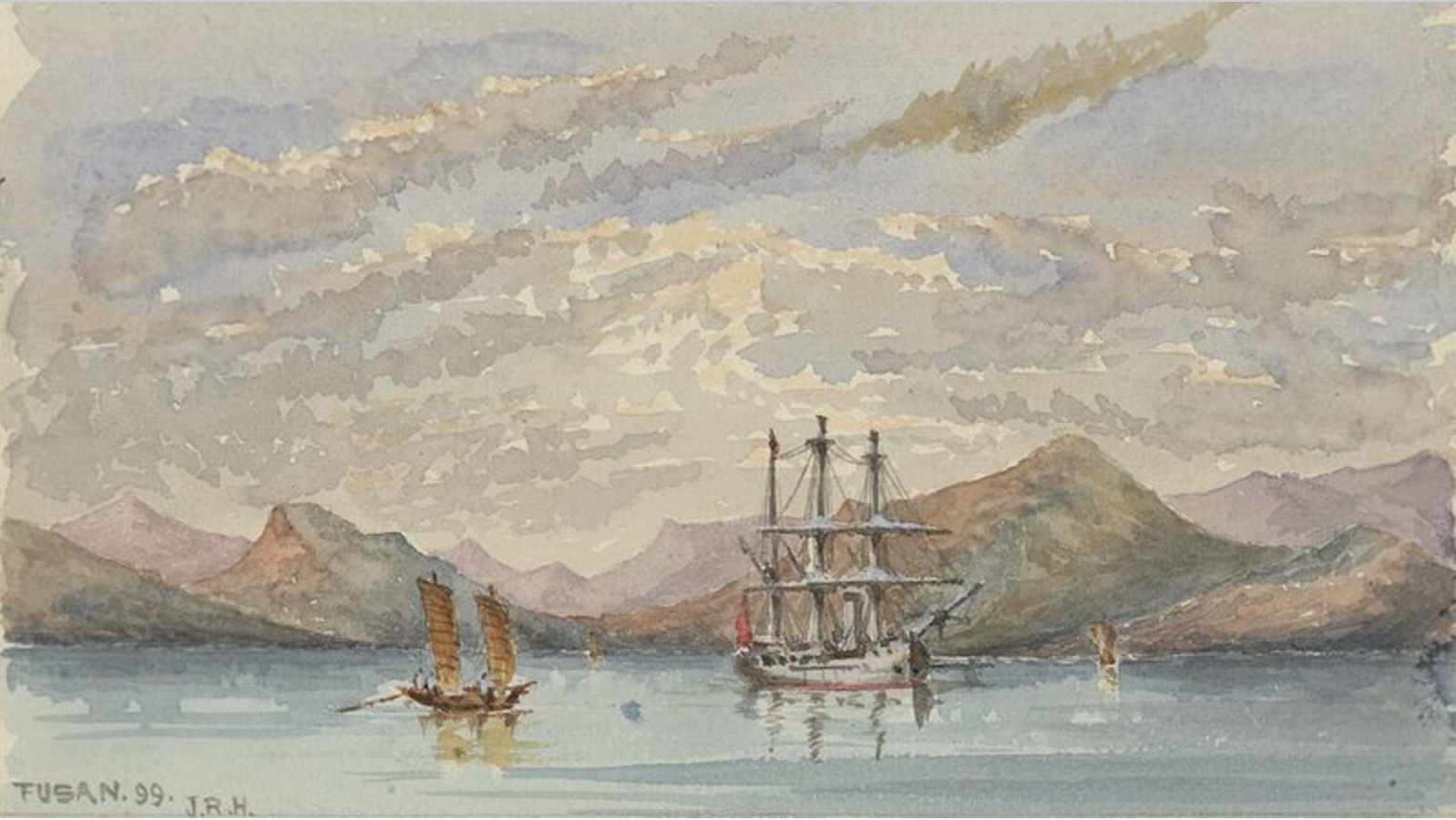

Broughton reached Korea in an 87-ton schooner, Prince William Henry, which he had purchased in Macau, to accompany his principal vessel, HMS Providence. (This was fortunate, as the Providence was wrecked near Okinawa, in May 1797.) On 16 September, having explored the Strait of Tartary between Sakhalin and Russia, he concluded that it offered no outlet to the north, and he turned southwards towards the Sea of Japan for an examination of the Korean coast.[8]

In the early stages, Broughton’s narrative comprises the dry language of the ship’s log. On 12 October 1797, however, it comes to life when Broughton saw fires on Tsushima, showing it to be inhabited. He also spied some Japanese junks working their way to the westward in the lee of the land. The shore was very rocky, and the ocean was breaking upon it ‘with great violence.’

On 14 October, Broughton hailed a fishing boat, and, under its guidance, he anchored in a sandy bay, in four fathoms of water (and steady rain and mist) half a mile from the mainland of Korea:

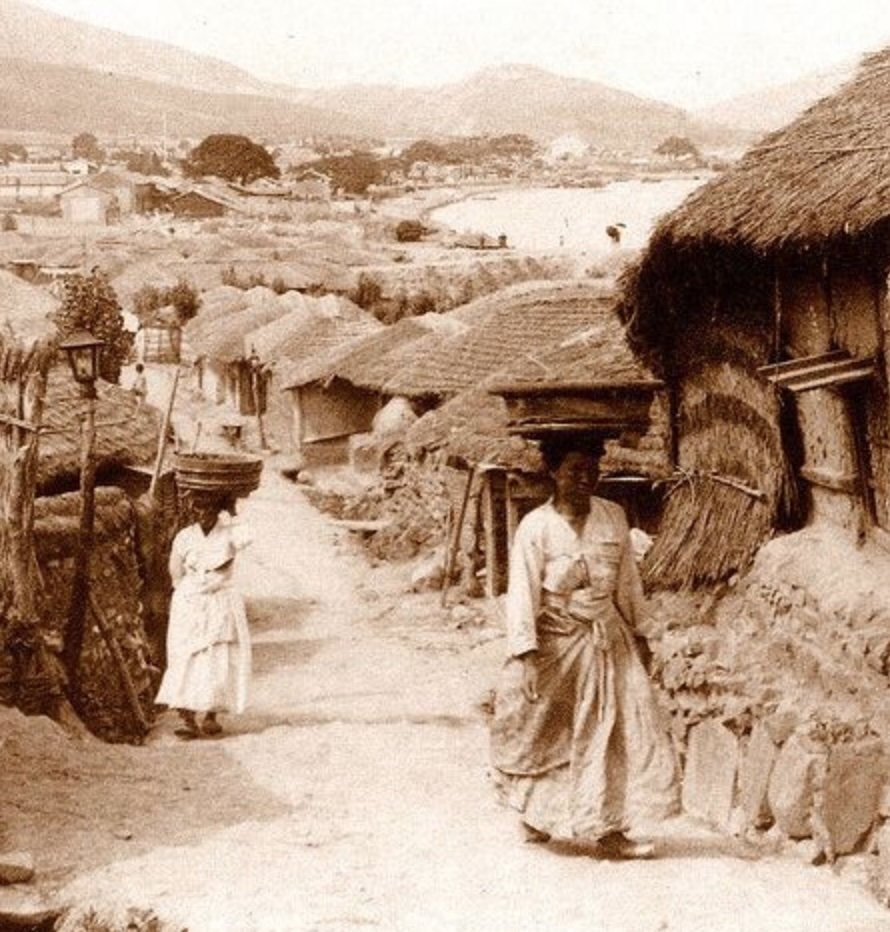

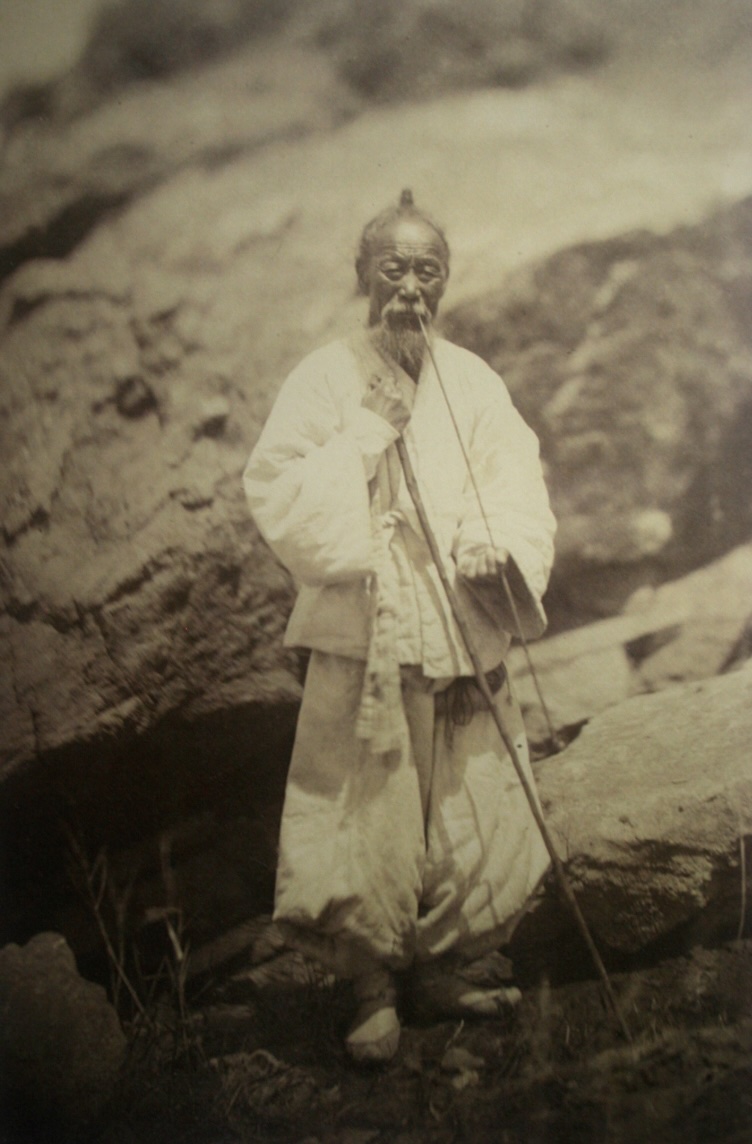

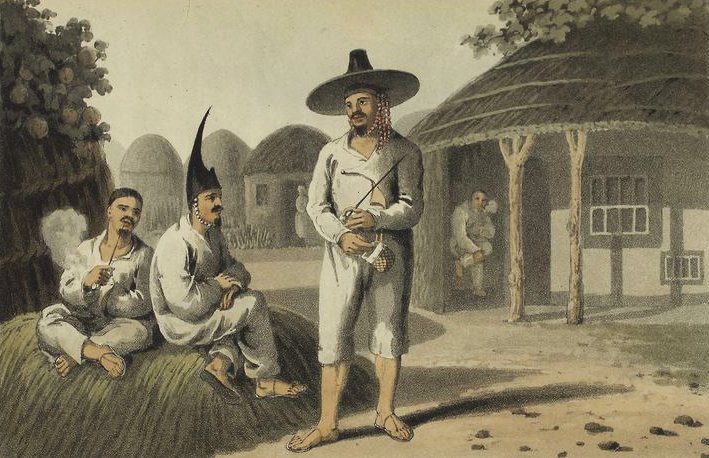

In the morning we had fair and pleasant weather & our Decks were soon full of Men, Women & Children, whose curiosity induc’d them to come off. They were universally cloth’d in Linnen garments made into Jackets and Trowsers, quilted or doubled & some of them [wore] loose Gowns. The Women wore a Short petticoat over their Trowsers & both Men & Women linnen Boots with Sandals made of Rice Straw. The Hair of the Men was roll’d up in a Knot to the Crown & the Women had theirs plaited & twisted round their Head.

As the mist cleared, the anchorage revealed itself to be in the extensive harbour of ‘Chosun’ (actually, Busan). Many settlements were scattered around its fringes, one of which – to the north – was a large town surrounded with battlements. Near it, several junks were moored in a basin protected by a mole. Another mole was located further to west, near some white houses of superior construction surrounded by a thick wood. The villages abounded with people, and the harbour was decorated with a profusion of boats.

The English went ashore to find wood and water and were permitted to take a walk. The accompanying villagers took pride in pointing out numerous graves ‘plac’d in an East & west direction & the Ground elevated over them some height.’ There was no sign of the inhospitality Broughton might have feared. In the afternoon, the party returned to their ship, where they were visited by some ‘superior people’, who were handsomely dressed and treated with great deference by the others.

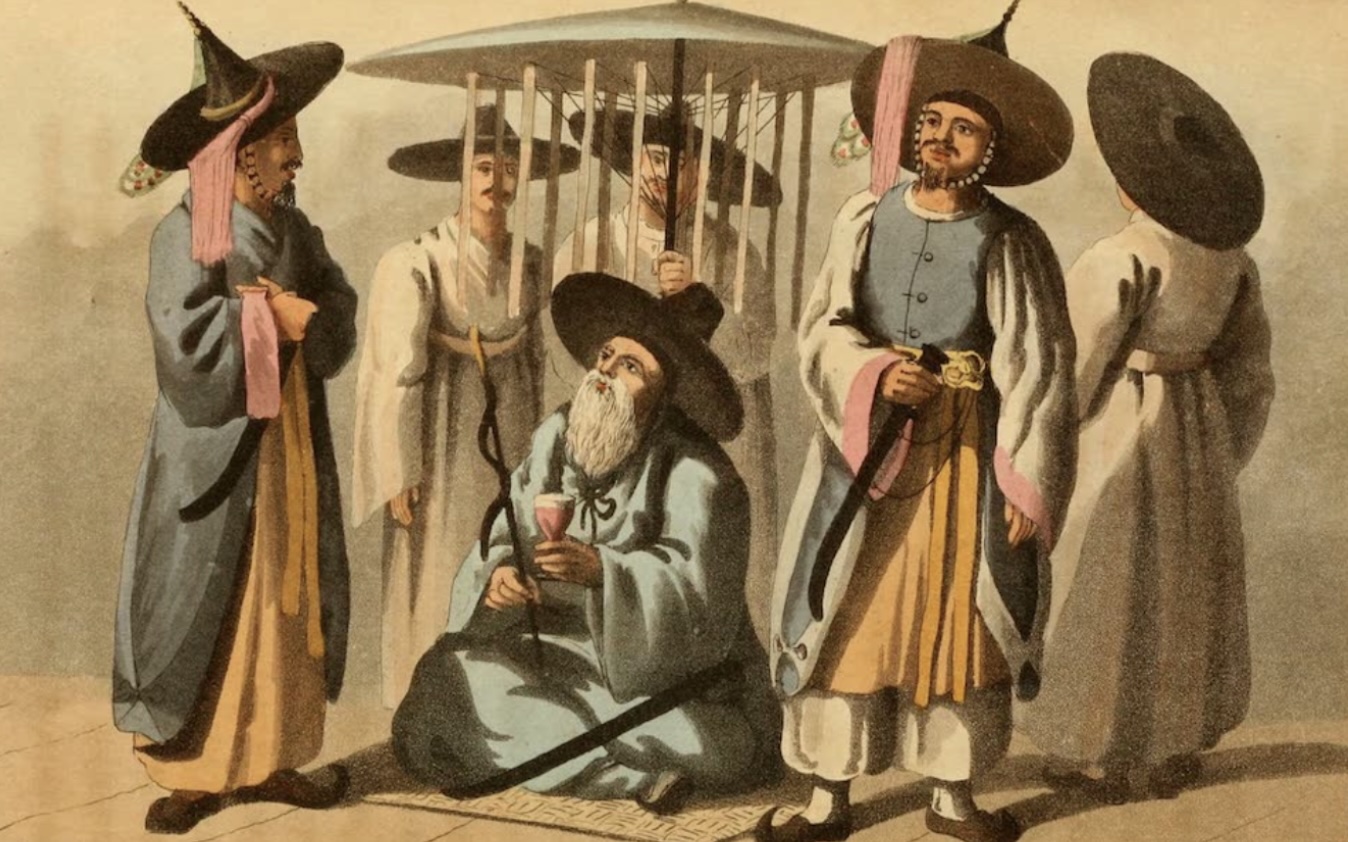

They all wore large black Hats with high Crowns & the Brims in Diameter were 3 feet. They tied [them] under the Chin & were manufactured with a strong Gauze not unlike Horse Hair, very Stiff and Strong making good Umbrellas. Each Person carried a Fan with perfume in a fillagree Box attach’d to it, also a Knife handsomely mounted in a Sheath, fasten’d around their Middles. A Boy attended each of them who had charge of their Tobacco Pipes & kept their Dresses Smooth.

Although the ensuing ‘conversation’ is best described as an exercise in mutual incomprehension, Broughton says the visitors seemed satisfied with their entertainment before they took their leave. Thereafter, however, the Englishmen’s nervousness about their welcome became more apparent.

After a brief survey ashore, Broughton returned to his ship to find it crowded with visitors. ‘Nor,’ he writes, ‘cou’d we get rid of them till near Dark, and then with great difficulty, using almost violence to get them into their Boats.’ Even then, some two hundred returned, desiring to come on board. When this was not permitted, they anchored alongside. Broughton writes that, as he was unsure of their intentions, he prepared for the worst. But the situation soon resolved itself. A boat with lights joined them from the shore and, after another ‘conversation’, the British were left to themselves for the night.

On 15 October, after breakfast, two boats approached with ‘Company Superior to any we had yet seen’:

Their Habits were made of the same form with the rest only of a finer kind. The Outer Garment of light Blue Gauze or Tiffany & under their Chins, as tying their Hats, with a bow over their right Ear was a String of Beads, some were of Agate others of Amber and one of their Hats tip’t with Silver in different parts.

It now occur’d to me these three Great Men were those whom we refus’d admittance to last evening, while our suspicions led us to suppose they had some other View to Gratify by coming so late. Their attendants and those in Office around them shew’d the most humble respect, always speaking to them & answering questions in a stooping posture looking on the ground.

They had in each Boat some Soldiers who carried Spontoons (halberds) or Spears with Flags of Blue Sattin, the field & their Arms in yellow Characters. Their Hats were decorated with Peacocks Feathers & with Bamboo sticks they kept the Boat Men & Populace on shore in Order by making great use of their Power. One of the principal Men who had been on board before, bro’t us a present of Rice, Salt Fish & Seaweed …

These visitors clearly desired that the Englishmen should be gone immediately, but Broughton requested that their depleted stocks of wood, water and refreshments should first be replenished. This the deputation agreed to, hoping thereby to hasten the strangers’ departure. (An exception was made in respect of some bullocks observed grazing on the shore: as ‘money Appear’d to have no value,’ and Broughton had ‘no other means to induce them,’ the crew had to bear their disappointment regarding the provision of beef.) At least the arrival of the dignitaries meant the ship was no longer besieged by quite so many visitors. Ashore, when the English went to make their astronomical observations, the crowds were sufficiently large as to make the task quite hard to perform, despite the attentions of some Korean soldiers.

For a few days more, Broughton’s men, with the villagers’ assistance, collected supplies, even as the elders besought the English to sail. By the afternoon of 18 October, the stores were complete but, on being urged again to leave, Broughton announced he would stay two days longer to observe the sun. On the following day, it rained without intermission. This permitted the Koreans to demonstrate the effectiveness of the parchment covers for their hats (and of their umbrellas) and allowed Broughton to make a discreet survey of the harbour. Quickly some boats were sent to fetch him back. When they came to discuss this excursion the next morning, the Koreans voiced their disapproval, warning him that if he landed by the white houses up the harbour, he would be ‘very ill treated, if not put to death.’ In this, they were not necessarily being unfriendly. The enclave was probably the Choryang Waegwan, the Japanese trading and diplomatic post established, in 1678, as the successor to the Dumo-po waegwan, the compound of the So of Tsushima, after the Imjin War. It was off limits to everyone, including Koreans. Again, Broughton was asked when he intended to depart and again he delayed, explaining that the sun had been obscured by the weather and that a swell was building. That morning, four guard boats were placed alongside his ship.

On 21 October, Broughton slipped away before dawn to complete a final sketch of the harbour unseen. Finding him missing, the Koreans were put to some agitation. Beacons were lit on the hills and boats sent in pursuit, but Broughton missed them and returned to his ship in time for breakfast. As the ship’s boat was hoisted aboard, he received a visit from one of the Korean dignitaries, who made plain his pleasure at seeing the British preparing to depart. Broughton presented him with a telescope and a pistol, ‘the only two Articles he seem’d desirous of possessing,’ and they parted ‘much please’d with each other.’ Shortly afterwards, the British sailed.

Broughton summarises the account of his stay in Busan with the remark that the reticence of the Koreans gave him little chance to come an informed opinion on their customs and manners. There were, he writes, several villages scattered about the harbour, all of them populous and most of them very pleasantly situated amidst the trees. The houses were small, of a single storey, and thatched, but unfortunately there had been little occasion to see what they were like inside:

We have to regret their Jealousy preventing our acquiring more knowledge respecting the Productions of this Country but in no Instance would they admit our researches. They were well acquainted with fire arms & Great Guns and yet During our Stay we saw no signs of any Offensive weapons whatever amongst them. Nor did they seem any way apprehensive of the small power we possess’d.

They only seem’d desirous we should Depart as soon as possible but pressing us at the time in a Civil manner … It should seem by their behaviour they are by no means desirous of Cultivating an Acquaintance with Strangers and yet many Articles we had very much excited their attention & Curiosity particularly our Woollen Cloathing.

As a Commercial People one would suppose they were conversant in Barter but they did not appear anxious to make any exchanges whatever. They have Horses & Black Cattle, Hogs & Poultry. On them I think they set a great Value, as we could not prevail upon them to Part with any. Money indeed they had no Idea of, at least our Coins & Spanish Dollars. Yet they fully Understood the Value of Gold & Silver of which they make use in the workmanship of the Knives &c.

The Koreans’ reluctance to engage in intercourse continued to puzzle Broughton. In his published account, he added:

They seemed to look upon us with great indifference, which I suppose was owing to the insignificancy of our vessel; or perhaps, their not comprehending what nation we belonged to, or what our pursuits were, made them solicitous for our departure, probably from a suspicion of our being pirates; or some other reason we could not divine.[9]

Leaving Busan behind, Broughton soon found himself in shoaling waters, surrounded by clusters of rocks and islets. Hazy conditions rendered navigation intricate and made it hard to identify a passage out. There were many boats about, but none approached until, on 25 October, one brought a written questionnaire, picked out in indecipherable characters:

About an hour after a very great Man attended by several Soldiers & other attendants came on board. This Boat was quite gay, the military being well dress’d carrying their silken Flags and one of Red & Purple much larger in the bow. Their motions were accompanied by Trumpets & every Man was armed with a Saber. This man of consequence was seated on a handsome Mat with Cushions to rest upon & Pillows. The cushion was cover’d with Leopards Skin. He ask’d many questions but we understood each other little.

He was seated upon the Deck his Suite keeping a most respectful distance & I set down with him upon his Leopard Skin. His principal enquiries however were to know our Numbers and to have them counted before him that he might be convinced. This was inadmissible on my part which seem’d to give some offence.

In contrast to the people in Busan, this distinguished personage was desirous the British should stay several days. He asked that they should send the ship’s boat on shore and was much surprised when Broughton again refused his request.

In the published account of his voyage, Broughton again added some extra colour to his description of this encounter, writing,

This man was particularly haughty in his manner, and treated us by his behaviour with the most sovereign contempt. After staying about half an hour he went away, leaving two boats with us as spies, as we supposed upon our conduct. They anchored close to us, and two others were sent away with messages.[10]

The private journal simply says that he crossed over to the point of a nearby island, having sent two boats away bearing messages and leaving two more near the William Henry, with his interpreter, who again vainly tried to count her crew. The private journal continues,

At 3PM the Haze having clear’d partly we got under way & stood between the Islands to the Westward. We soon observ’d the Great Mans Boat to follow us Hollowing and sounding the trumpets for us to stop, to which we paid no attention. We soon perceiv’d he landed with the other Boats on the point of the Island we pass’d while we pursued our course with a strong Breeze. What this Man’s intentions were I cannot positively say, but to me they appear’d suspicious and I did not want to see the result of them at the expense of Losing the clear weather.

That was the last interaction between the British and the Koreans on Broughton’s visit. He saw several fishing boats as he cruised about the archipelago, but he could not induce them to approach. On 27 October, he bore off to ‘Quelpaert’, the name by which he knew the island on which Hamel had been shipwrecked. Then, after a few days’ exploration, and with his narrative reverting to its former dry style, Broughton made for Macao.

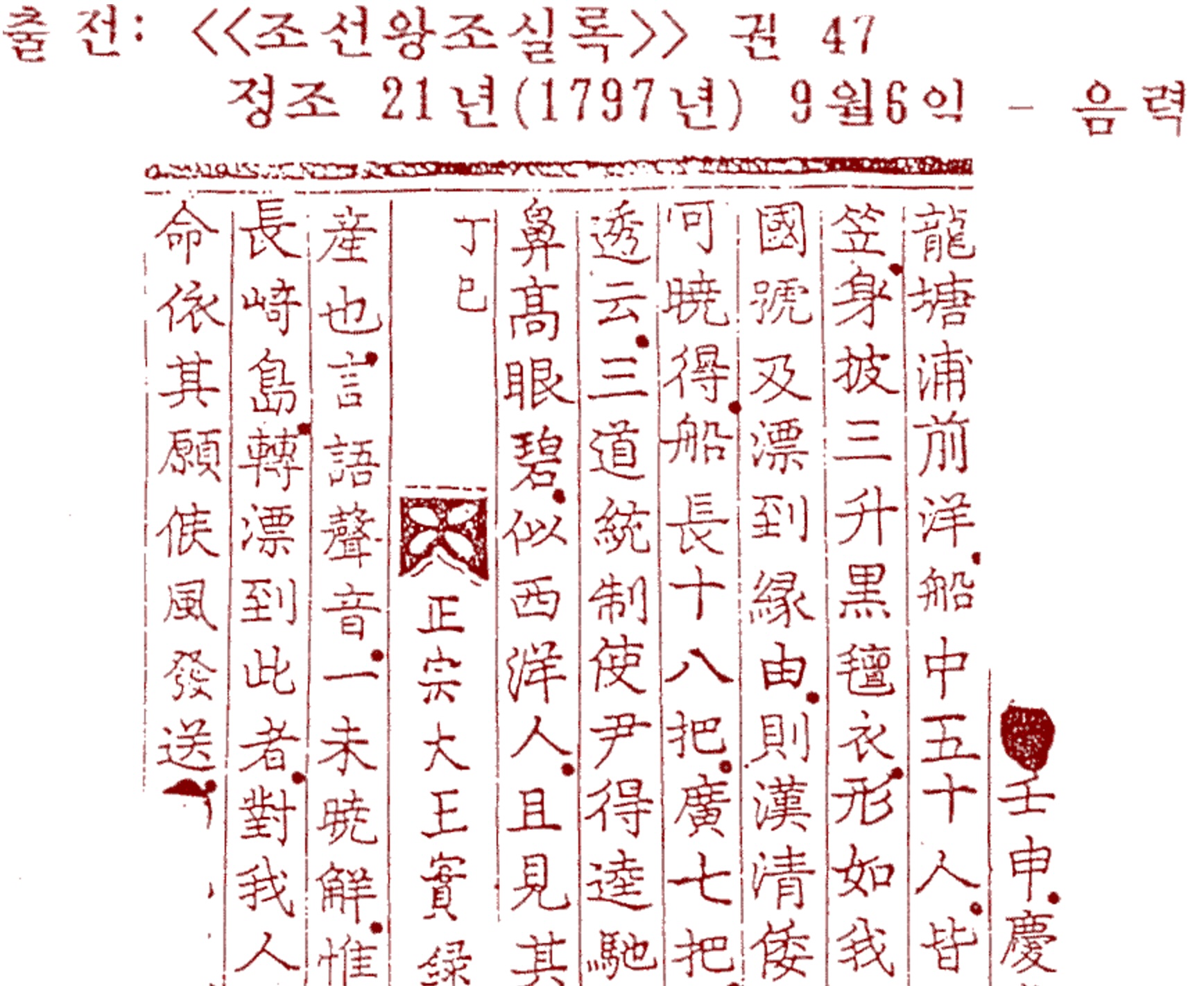

However, it is not quite the end of the episode, because we have a report from the Royal Chronicle of the Joseon Dynasty, which gives us the Koreans’ impressions of the British:

On the day of Imshin (6 September 1797, Lunar Calendar), the Governor of Kyongsang Province, Lee Hyong-won, came running and reported the following in writing: ‘A strange ship from a country arrived off the Yong-dang-po Bay, Tongnae County. There were 50 people in the ship. All of them had their hair tied or pulled back. They wore either hats made of thick white material on their heads, or hats made of wisteria. The shape looked just like our warrior hat. They dressed themselves in thick black material, 3 Dae long. The shape looked like Hyopsoo in Korea. They wore thin trousers. They were high-nosed and blue eyed. They were asked to answer the name of their country and why they came to Korea after having drifted at sea. They neither knew nor understood any Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian. We provided them with brushes to write and their writing resembled mountains covered with clouds. Though pictures were drawn, we still could not understand. The ship was 18 Bal long (30 metres) and 7 Bal wide (7 metres). Cedar wood was used for both the left and right planks of the ship, which were all covered with copper plates again. They were firm, elaborate, exquisite and complete so that there was no leakage even in water.’

At this point, Yoon Duk-kyu, the admiral in charge of the province arrived. He reported that,

… the cargoes in the ship were all western goods such as glass bottles, telescopes and silver hole-less coins. We could not understand their language and pronunciation at all, but we could realise only a four-syllabled word Nang-ga-sa-gee, which referred to the island of Nagasaki in Japan. It seemed that this merchant ship arrived here after having drifted here and there from the island of Nagasaki.

Looking at us, they pointed their hands to the vicinity of Tsushima, motioning the wind by blowing with their mouths as if they were waiting for the right wind. Orders were given to them and we had them sail after having waited for the wind to be in their favour.[11]

That was a relief, then – and not entirely misplaced, as it was to be nearly twenty years before another ship commanded by a high-nosed Briton cast her shadow upon the Korean coast.

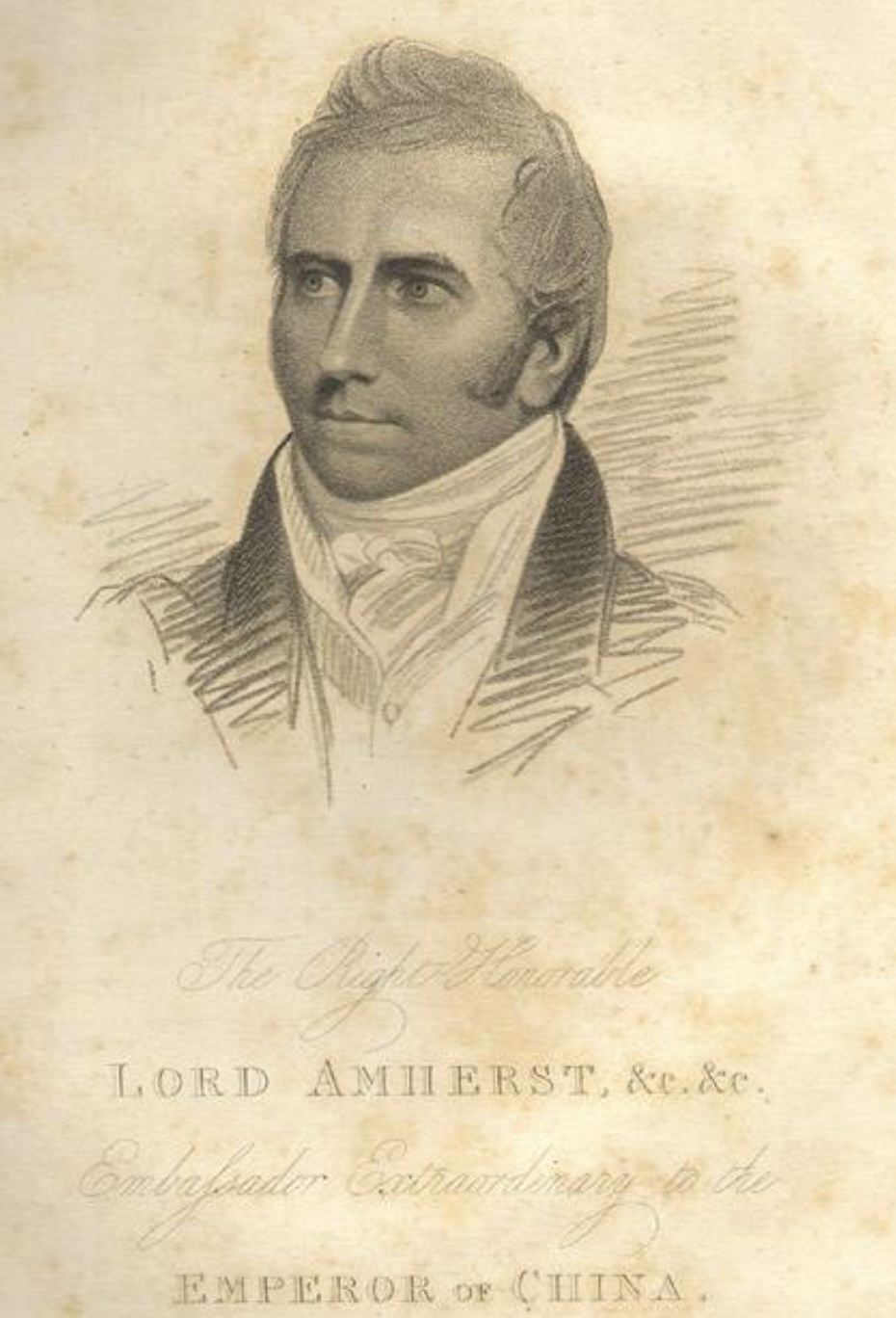

The Expedition of Murray Maxwell and Basil Hall (1816)

Even without the company of the ten-gun brig Lyra, HMS Alceste would have appeared much more imposing to the Koreans than Broughton’s vessel of nineteen years earlier. She was, in fact, a French Armide-class frigate (Minerve) which had been captured off Rochefort by HMS Monarch, in September 1806. With a keel length of 129 feet, she was thirty-nine feet longer even than HMS Providence had been, and she had a crew of around three hundred.

HMS Alceste left Spithead, on 9 February 1816, and joined the Lyra in the Bohai Sea, at the end of July. After Lord Amherst and his suite had been landed at Taku, on 9 August, the two ships separated, the Alceste exploring Liaodong Bay, north of Dalian, before reuniting with her escort on the northern side of Shantung, at the end of the month. From there, on 29 August, they sailed directly east, along the thirty-eighth parallel, towards the coast of Korea, a country,

… so completely unknown that it held no place on our charts, except that vague sort of outline with which the old map-makers delighted to fill up their paper, and conceal their ignorance.

The coast proved to be rather further to the east than expected:

… for on approaching the land, and making observations to ascertain our true place, we discovered that according to one authority, we were sailing far up in the country, over wide forests and great cities; and according to another, the most honest author amongst them, our course lay directly through the body of a goodly elephant …[12]

First landfall, on 1 September, was at a group of islands, which Maxwell named after Sir James Hall, an eminent geologist (and Basil’s father).

The inhabitants, who received us with looks of distrust and alarm, were evidently uneasy at our landing, for they were crowded timorously together like so many sheep. Having tried every art to reassure them, but in vain, we determined … to take a look at the village. This measure elicited something like emotion in the sulky natives, several of whom stepped forward, and placing themselves between us and the houses, made very unequivocal signs for us to return to our boats forthwith …

Hall remarks that these people resembled the Chinese neither in dress, nor language, nor appearance. In their manners, they lacked Chinese courtesy, being ‘a much ruder people.’ Some of his party went so far as to term them ‘savage’ and, although Hall considered this harsh, he himself found their faces, which were of a dark copper colour, ‘rather forbidding.’ There was, he writes, ‘something wild about them, although not amounting to ferocity’:

Their hair, which was black and glossy, was twisted into a curious conical bunch, or spiral knot, on the top of the head, and there was not the least appearance of the Tartar tuft. Two or three of their number, who seemed principal persons, wore vast hats, the brims of which extended a foot and a half in all directions, so as to completely shade the body of the wearer. The top, or crown was disproportionately small, being made no larger than just to fit the top-knot of hair, which stood eight or nine inches above the head.

Immediately, it transpired that the expedition’s Chinese interpreter (a servant of the embassy accidentally left behind by Amherst) was quite unable to communicate with the villagers. The party retired to the top of a nearby hill, where, enchanted by the scene of countless islands, they took a picnic. Returning by another route, they caught sight of the women of the village who, their children strapped to their backs, were engaged in husking rice by beating it in great wooden mortars – until the arrival of another of the ship’s boats sent them scattering to their huts, ‘like rabbits in a warren.’

Gradually, the natives grew less apprehensive. They permitted the strangers to walk amongst their houses, which were scruffy affairs constructed of reeds and mud, with thatched roofs tied down by straw ropes. Maxwell and Hall tried to purchase some bullocks and poultry, but without success. They offered dollars, but they elicited no interest. The only items which seemed to catch the villagers fancy were the wine glasses in the picnic basket. Even then, they could hardly be induced to keep them:

One of the principal persons, or a man whom we assumed to be such from the dimensions of his hat, looked so wistfully at a claret-glass … that we prevailed him to accept it. … But in a few minutes the same native came back, and without any ceremony thrust the glass again into the basket, and walked off, accompanied by all the party except one man, who the moment the angle of a rock concealed him from the view of his companions eagerly pointed to a tumbler in use at the moment to lift water from a spring, and having carefully hid it in his bosom, returned to the village by another road, evidently apprehensive of being detected by his countrymen.

When Hall attempted to buy an unusual rake, its elderly owner gave him ‘a violent push … followed by many abundantly significant gestures, implying that the sooner I took to my boat, and left him and his inhospitable island, the better he was pleased.’ Hall complied. The Koreans, he decided, were the most resolutely unsociable people he had come across, though he conceded that ‘a disdainful sort of sulky indifference, rather than any direct ill-will, was the most obvious trait in their deportment.’ His party were unsure of what to expect next, but they sailed away in high spirits, confident that they would soon encounter fresh surprises.[13]

The next port of call was a small island a little to the south-east, the geology of which was sufficiently noteworthy to merit investigation by the scientists of the party. (The island was named after James Hutton, the proponent of geologic time.) Whilst the research was being conducted on the beach, a party of islanders assembled on the cliffs above, indicating ‘by indignant shouts, and the most significant, though ill-mannered gesticulations’ their anger at the posse of cognoscenti hammering at the rocks two hundred feet below.[14]

For fear that their clamour might be supplemented by ‘the more potent argument of a shower of stones,’ the party rowed around to a beach on the western side of the island. As the natives approached, Maxwell and Hall doffed their hats and made a low bow. Their gesture was returned with a long speech by the foremost villager, the essence of which was apparent to those board ship half a mile away. Unable to explain in words their peaceful intentions, the English made for the brow of a nearby hill:

The natives put a negative on this resolution as far as they could, without using absolute violence. Sometimes they placed themselves directly across our path; and sometimes bawled in our ears some very angry words, at the full stretch of their voices, apparently impressed with the belief that mere loudness would make their words more intelligible.

(A fine case of the English pot calling the Korean kettle black.)

… One very busy personage now took his station before us, and baring his neck, drew his fan from end to end across his throat. … Hereupon a great speculation was set afloat amongst us, as to the import of this significant gesture. One thing was plain; it had reference to cutting off heads, but our party was equally divided as to whose heads were to suffer. Some thought the natives were in alarm for themselves, while others considered this ugly sign a threat to us.

After a pause to take in the view, the party started back towards the boats. Instantly the mood changed:

… instead of obstructing our way, and roaring in our ears, they were all smiles and assistance; a man on each side seized our hands, and warning us of every obstacle, escorted us along the path, and over the slippery stones on the sea bank, with a degree of assiduity extremely ludicrous.

There was a moment when the sight of a watch caused the Koreans to crowd around in wonderment. One was demonstrating to his fellows, by pressing it into his hand, that it was some kind of seal, when a member of the crew fired his fowling piece. This sent everyone scattering ‘like a shoal of fish when a stone is cast among them.’ It was time to be off.[15]

In the morning, the two ships threaded their way on a glass sea between the islands towards the mainland. That afternoon, they anchored in a sheltered bay behind a point of land (Hijin-wan, near Seocheon), which they named after Basil Hall. Ashore there was a commotion ‘resembling the sort of bustle into which a colony of ants are thrown by the thrust of a spade.’ Maxwell and Hall headed for the beach. They were met by a fleet of more than a hundred boats of all sizes. They were decked out with streamers and crowded almost to sinking.

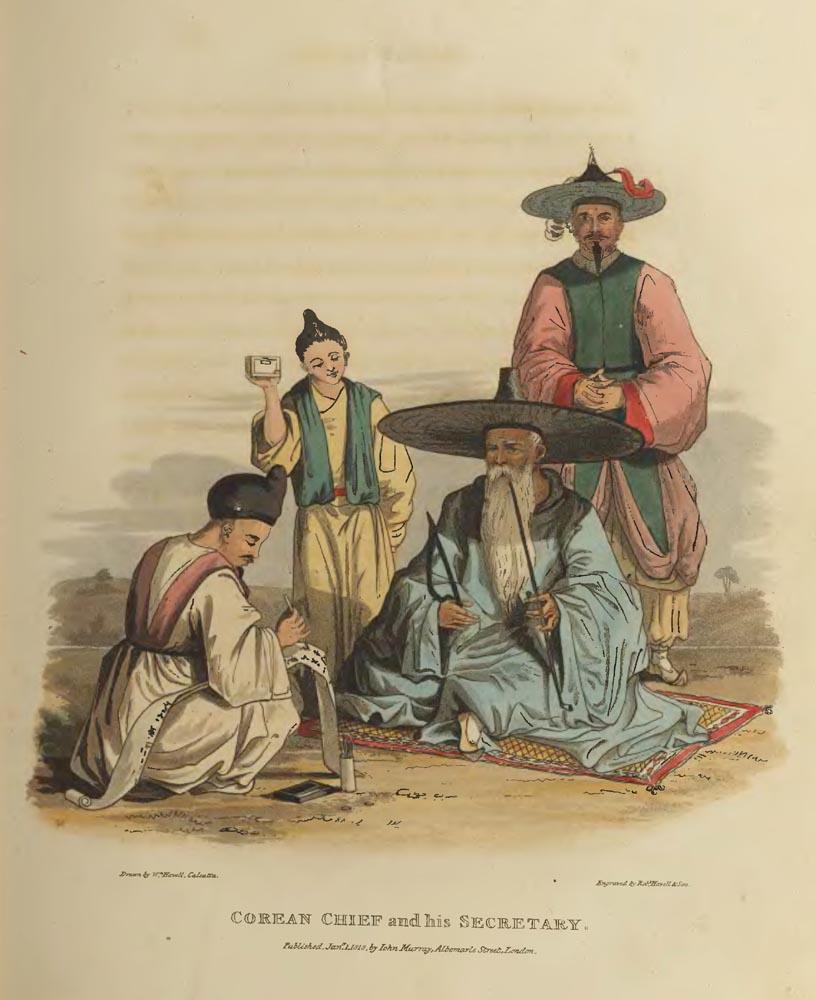

On arriving within a couple of boats’ lengths of the headmost vessel, our ears were saluted with sounds not unlike those of the bagpipe, which issued from three pipes, or trumpets, played by men raised high in the bow of the boat. In the middle part of the deck, between the masts, we discovered a huge blue umbrella, held by two men over the head of a very important-looking personage, seated cross-legged on a mat, surrounded by attendants in richly-coloured dresses.

This fine patriarchal figure was half-hidden in an ample robe of blue satin. His full white beard reached down to a richly embroidered girdle around his middle. In his right hand he wielded, with an air of importance, a silver-tipped black rod, with a leather thong at one end, and a piece of black crepe tied to the other. In his left, he grasped his pipe, which was trimmed from time to time by an attendant, who took the tobacco from a silver box carried by another boy.

Maxwell and Hall crossed over to the chief’s boat and realised almost immediately that they had committed a faux pas. Since the press of the vessels made them uneasy, they proposed that everyone repair to the Lyra. Reckoning the ship’s cabin was too small to accommodate the chief’s hat, which was of the usual broad-brimmed variety, it was decided to entertain him on the quarterdeck. Chairs was fetched, but refused: ‘the chief seemed to despise these European inventions, and would accept of no accommodation but his own mat.’ After he was seated, the men from his boat, and about twenty others, leaped on board, climbing the rigging, crowding the poop, and forming a line, from stem to stern, along the hammock netting.

Once the necessary decorum had been established, the chief launched into an oration lasting five minutes, unaware that his audience (including the interpreter) understood nothing. There was a pause. The chief turned to his secretary, who rubbed a cake of Indian ink on a blue stone, drew forth a camelhair brush and wrote a dispatch at the chief’s dictation onto a long scroll of paper. It was handed over. Maxwell signified his lack of understanding with as much grace as he could manage. The chief was mortified, ‘and showed by his gestures and the angry tones of his voice how stupid he thought us.’

A glass of cherry brandy was produced, and the old man’s disturbed features became smooth. Rum was distributed to the rest of the assemblage and the situation was salvaged, although the chief seemed to be sitting on thorns and could not help issuing orders to his people in what appeared to be a petulant manner.

Finally, as it grew dark, he signalled it was time to leave. With some difficulty, he returned to his boat, but instead of shoving-off, it remained alongside, the chief sitting still and silent, his pipe in his mouth. Unsure of what this meant, Maxwell and Hall decided they should return his visit. When they were seated on a corner of his mat, he looked about as if in distress at having nothing to cheer them with. A bottle of wine was sent for and given to him. It was poured into bowls, which he touched with his rod to indicate that Maxwell and Hall might have a taste. The oddity of his entertaining them at their own expense seemed not to discomfort him one jot.

After a pleasant interlude, the chief made to leave but, this time, instead of returning to the shore, he steered towards the Alceste. Maxwell had just enough time to reach her first, and to change into his coat and epaulettes. This time, the cabin was thought large enough to fit the chief’s attire. Its interior made a powerful impression, and, for a second time, he was invited to take a seat. Again, however, he asked for his mat. After a few minutes, this was retrieved from the press at the door. A problem of decorum then asserted itself. According to John Mcleod, surgeon on the Alceste:

It appearing to be etiquette for the head to be covered, the whole party, consisting of Captains Maxwell, Hall, and other officers, conformed to this rule, and, squatting on the cabin-floor, with gold-laced cocked hats on, amid the strange costume of the Coreans, looked like a party of masquers.

The chief now asked to inspect a mirror which had caught his attention. When it was handed to him, he seemed rather pleased with the image it presented and continued for some time pulling his beard from side to side. Then he spied one of his attendants looking over his shoulder. This quite upset his good humour. The attendant was scolded stiffly and dismissed from the cabin. It seemed scarcely five minutes could pass without the chief finding fault with his people – behaviour which the British suspected was designed to signal his importance. Hall continues,

… whether or not this fretfulness was feigned while in the cabin, no one could doubt the sincerity of his displeasure a minute after he came onto the quarterdeck to take leave. On passing the gunroom skylight, his quick ear caught the sound of voices below, and looking down he detected some of his people enjoying themselves, and making very merry over a bottle of wine with the officers of the ship. On his bawling out to them, they leaped on their feet, and hurried up the ladder in great consternation.

Shortly afterwards, there emerged through the hatchway another group of tipsy Koreans, who had been carousing with the midshipmen. As they staggered onto the deck, the chief pushed them about with his rod to signify his acute displeasure. One, who had hidden a handful of biscuits in the sleeve of his robe, secreted them away in a coil of rope, but he was discovered, after being chased around the quarterdeck, to the considerable amusement of the crew. The chief rummaged about for more under the guns and around the main mast, but nothing was revealed, and he departed, Hall helpfully pointing out to the sleeping sailors of his escort that they needed to pick themselves up, if they were to catch him before he reached the shore.

At daybreak the following morning, the Lyra’s crew woke to the sound of gongs and martial music. The chief was on his way again, this time accompanied by another man of rank, whose urbanity earned him the epithet ‘the Courtier’. Breakfast not being ready, Hall took them on a tour of the lower deck. The cramped conditions meant that the state hat, which had been resolutely kept on despite the inconvenience, had to come off – much ‘to the old boy’s evident mortification.’ However, he was soon in his element, ‘turning everything he could lay his hands on topsy-turvy’:

He next went into the kitchen, where he lifted the lids from the cook’s boilers, dipped his little rod into the boiling cocoa, and inspected all the tea kettles and coffee pots. The lustre and sharpness of one of the ship’s cutlasses delighted him so much that I asked him to accept it. The offer seemed to produce a great struggle between duty and inclination, but it was of no long duration, for, after a moment’s consultation with the Courtier, he returned the glittering weapon to its scabbard, and, as I thought with a sigh, returned it to its place. What his scruples were on this occasion I could not imagine, for he had no such delicacy about anything else, but seemed desirous of possessing samples of almost everything he saw.

Indeed, by the time the tour was finished, the immense sleeve into which the chief had stashed his winnings hung down ‘like the pouch of an overgorged pelican.’ (By contrast, the Courtier, who had been given one of Hall’s books and had insisted on giving his fan in return, when discovered, was given a look that left him ‘ready to sink into the ground with fear.’)

The party re-emerged on deck, where a carronade was fired for the chief’s benefit and with the muzzle so depressed that it sent its shot skipping across the sea. ‘Had a thunderbolt fallen amongst the natives, it could not have astonished them more,’ says Hall. They could scarce believe their senses when it was revealed that the shot had weighed thirty-two pounds.

At this juncture, Maxwell transferred to the Lyra and the group retired to the after-cabin for breakfast. The hosts were delighted that the chief took sugar and milk with his tea, ate heartily of his hashed pork, and insisted on using a knife and fork when he did so. Hall comments,

The facility with which this Corean chief, who but a few hours before must have been entirely ignorant of our customs, could accommodate himself to our habits, was very remarkable. On many occasions where he could not be supposed to act from our immediate example, he adopted the very same forms which our rules of politeness teach us to observe; and if we did not deceive ourselves, this observation which was actually made at the moment, is so far curious as it seems to show, that however nations differ in the amount of knowledge, or in degrees of civilization, the usages which regulate the intercourse of all societies possess a striking uniformity.

The English now signalled they were ready to visit the town, as they imagined they had been invited to do the evening before. In this they were mistaken, but they persisted, and the chief resisted, even to the point of crossing into Maxwell’s gig, as if to show he was travelling under compulsion. When they reached the beach,

… he held up his hands in despair, drooping his woe-begone countenance on one side, and drew his hand repeatedly across his throat, from ear to ear, unequivocally implying, that some one or other must lose his head on this occasion. … We tried to signify that our wishes went no farther than to walk about for half an hour … after which it was our intention to return on board to dinner … [H]is only reply was to repeat the beheading motion. … ‘How can I eat with my head off ?’ was the interpretation suggested by the late Dr. Mcleod, a man of infinite jest … The humorous manner in which this was spoken, made all our party laugh; but our mirth only augmented the chief’s distress, and we began seriously to fear that we had proceeded too far.

The party was now surrounded by a hundred or so natives. They grew concerned that they might pay dearly for their curiosity. Against their worst fears, however, the chief instructed his escort to disperse the crowd, which they did by pelting them with stones, ‘thus inverting the usage of more polished communities, where these missiles are the established methods of the mob.’ The mood of the morning had been lost and the English returned to their ships. When the chief paid a final visit, his sprightliness had given way to stately civility. Maxwell tried his best to recover the injury which the party had caused. The gift of a Bible was accepted, and it was thought they departed mutual friends.[16]

From Basil’s Bay, the Alceste and Lyra sailed south-west through an immense archipelago, in the process getting a proper appreciation of the strength of the tide and the risk it posed. Hall and Maxwell fell in with no more officials like the chief, but they did explore a couple of villages, largely deserted, where they endeavoured to make friends with those natives who remained. In this they were partly successful – they shared their pipes and some of their wine – but the acquaintances they made maintained their reserve, and most of the remainder went into hiding.

On the last evening, as they were returning from one of their excursions onshore, they came across a small village which they decided to explore before dining, in hope of finding some natives to join them:

It was nearly deserted, for only two of the inhabitants remained. One of these was a very plain old lady, who took no notice of us, but allowed us to pass her door, before which she was seated, without even condescending to look up. The other was a middle-aged man, industriously employed in the manufacture of a straw sandal. … In order to rouse this stoical and industrious Corean, we thrust a button into his hands, which he received without the least show of gratitude, and put into a bag lying near him, but still went on with his work.

When another button was exchanged for some of this man’s handywork, Hall remarked, with irony, that it represented ‘the only instance during our visit to Corea of anything like traffic.’

He continued,

We made signs that we wished to examine his house, – that is to say, we opened the door and walked in. But even this proceeding elicited no show of interest in our phlegmatic shoemaker, who seizing another wisp of straw, commenced a new pair of sandals, as deliberately as if we had been merely a party of his fellow-Coreans inspecting the dwelling, instead of a company of European strangers, unlike what he could ever have seen before, or was ever likely to see again.

Finally, during dinner, the British spotted the heads of five or six natives peeping at them over the top of a nearby hill. Surreptitiously, the villagers crept forwards and one of them, on an impulse, offered Captain Maxwell his pipe. In return, he received a bumper of wine, which he drained in one, calling to his friends as soon as he had done so. In no time, a party was in full swing, several bottles were finished and, as Hall puts it, ‘there was some reason to hope that the difficult passage to a Corean’s heart had been discovered.’ Then it was realised that the sun was setting. The Koreans called an immediate end to the jollity and, signalling that it was time for bed, escorted the British to the water’s edge ‘and expressed the most lively satisfaction when they were fairly rid of us.’[17]

So ended the last interaction of any consequence between England and Korea until the arrival of Hugh Hamilton Lindsay, in 1832. Yet, it’s worth sticking with the crew of the Alceste for a little longer.

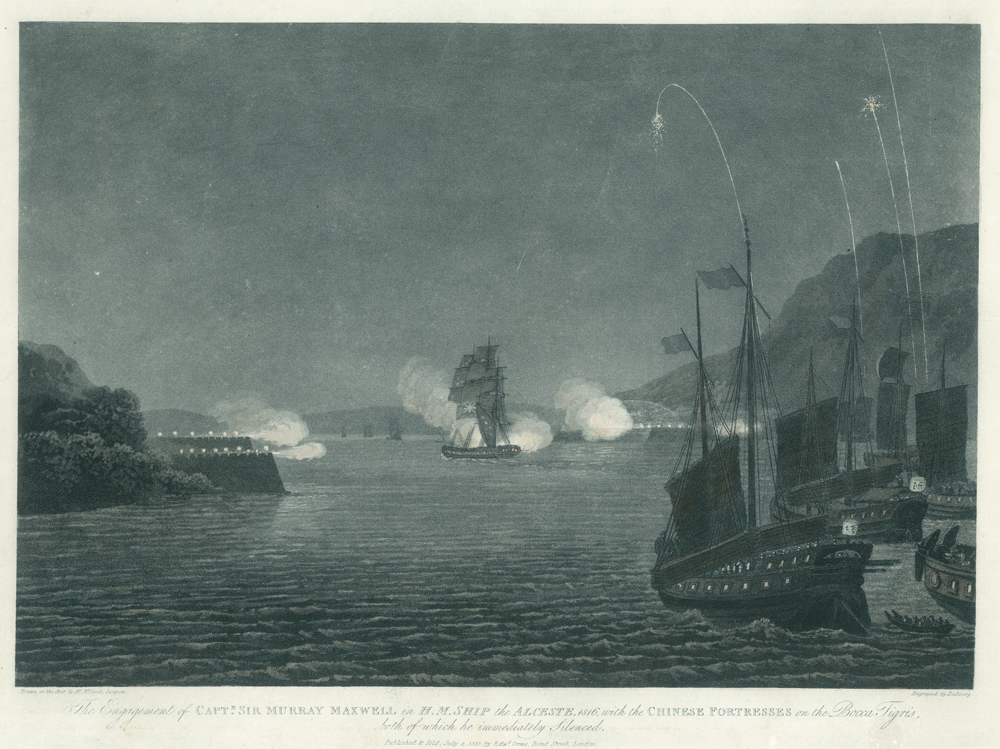

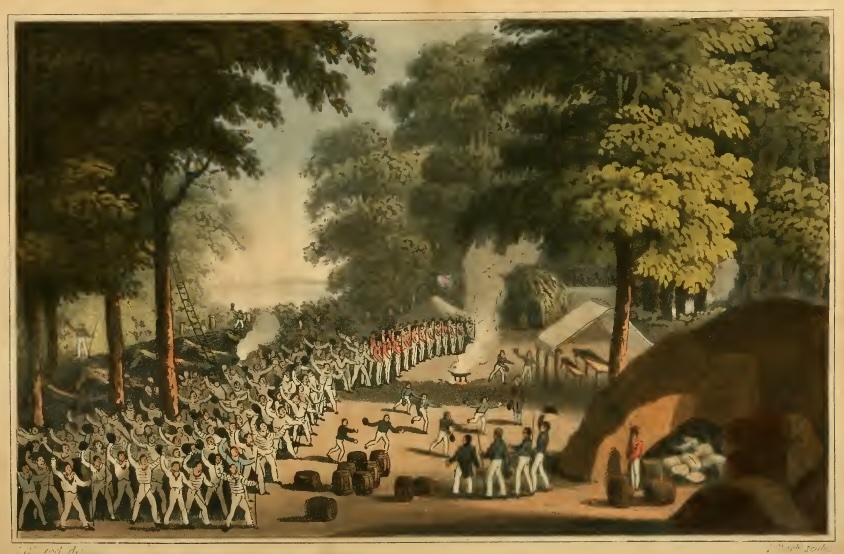

From Korea, Maxwell sailed to the Ryuku Archipelago (‘the Loo-Choo Islands’). There, he spent six weeks conducting a survey before he returned to the Pearl River, on 2 November. The passage through the Straits of Formosa had been ‘boisterous in the extreme,’ but Maxwell’s request to proceed to a secure anchorage for caulking and other repairs met with a blunt rebuttal. Canton’s viceroy knew that Amherst’s embassy had been ‘in a great measure directed against his extortions.’ Deciding the Chinese response was an act of ‘absolute hostility’ and that submission would encourage more of the same, Maxwell forced his way past the forts on the Bocca Tigris, on the evening of 13 November, in an incident that was later euphemistically termed a ‘chin-chinning’, or an exchange of salutes. Finally, with Amherst’s suite on board, the Alceste departed for England, on 21 January 1817.[18]

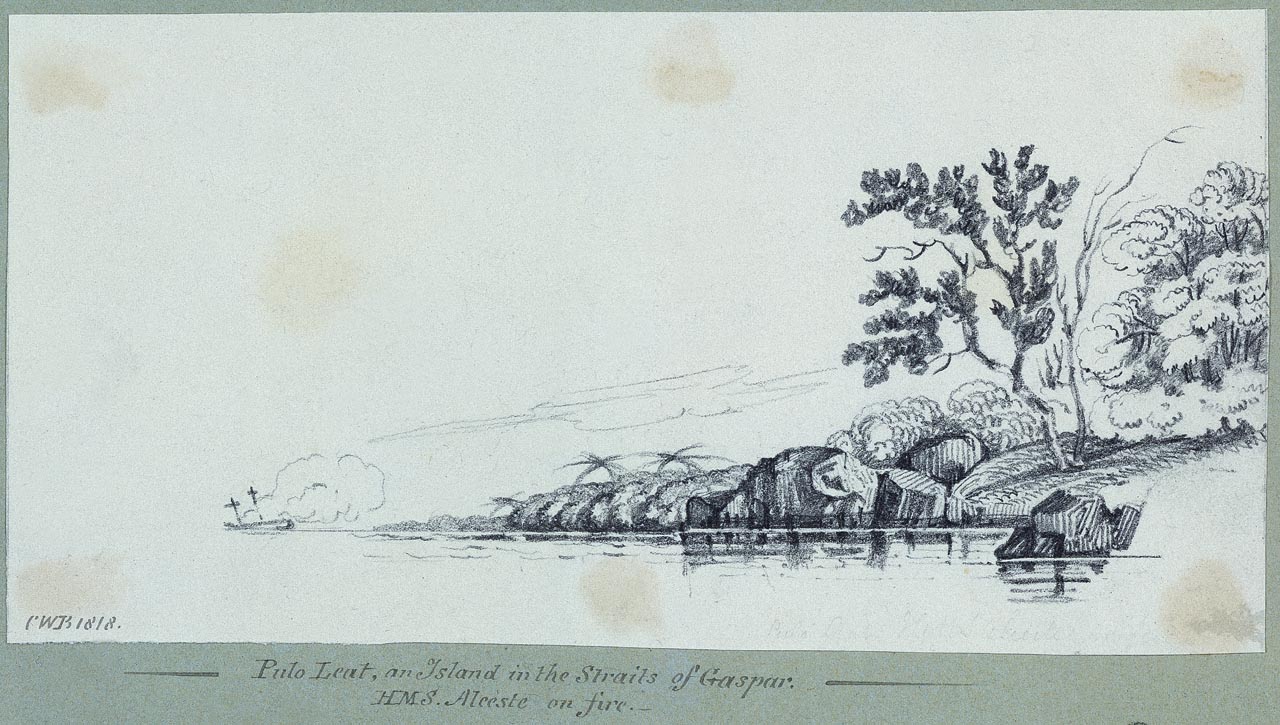

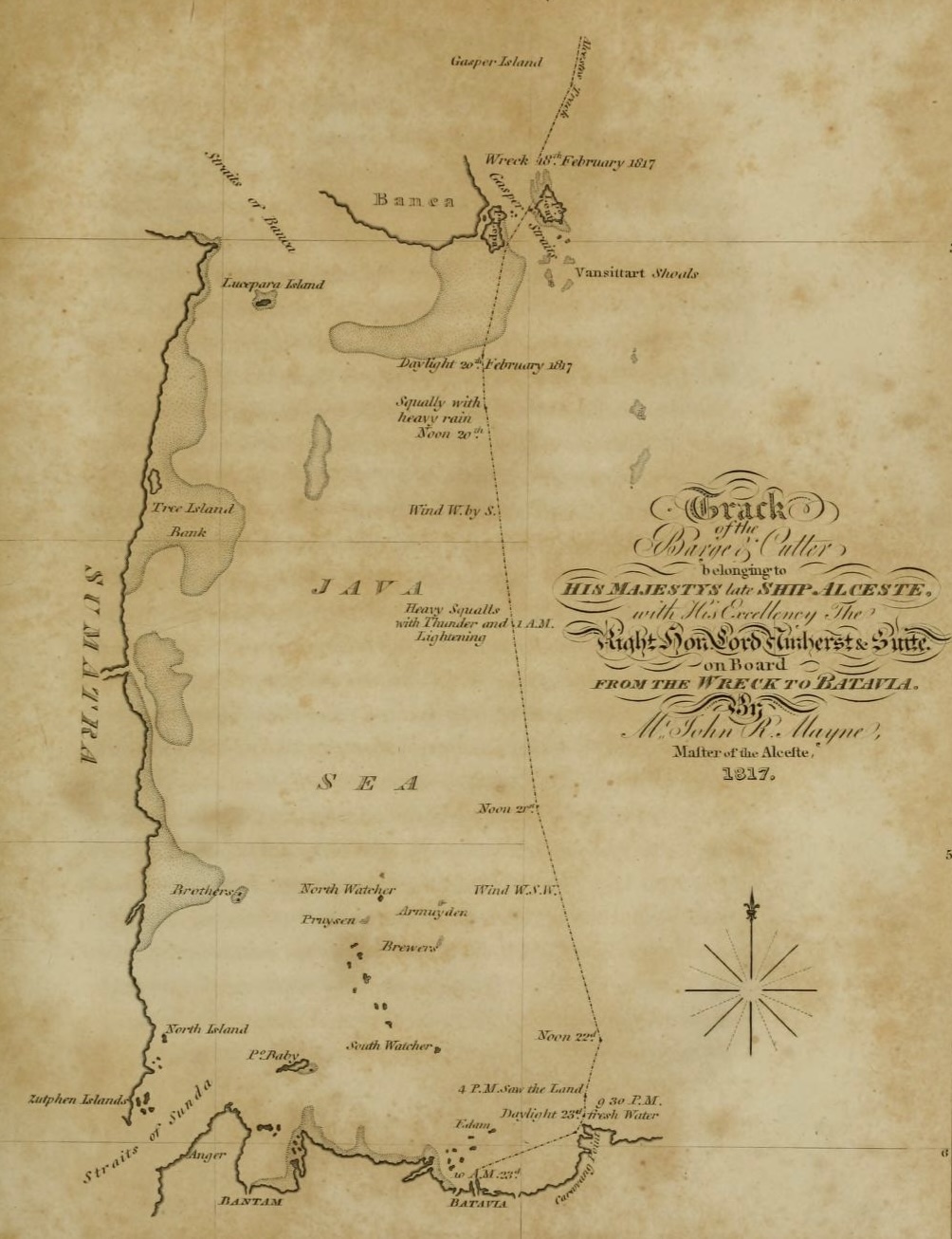

She was not destined to reach it. On 18 February, she struck an uncharted reef in the Gaspar Strait between Pulau Bangka and Pulau Belitung, about 275 miles north of Jakarta. Fortunately, though severely holed, she stuck fast and did not sink. This gave the crew sufficient time to reach safety on the island of Pulau Leat, three and a half miles away. However, there was a shortage of water and of serviceable boats, so it was decided that a guard should escort Lord Amherst and his suite to Java, to fetch help. With them went a side of mutton, a ham, a tongue, twenty pounds of biscuit, seven gallons of water, and (most importantly) the same of beer, as many of spruce, and thirty bottles of wine.

Maxwell remained with two hundred men and boys, and one woman, to salvage what they could from the wreck for their survival.

This turned out to be a harder task than expected because the area was infested with Dayak pirates. Having been driven off the wreck in his first effort at salvage, Maxwell ordered the construction of a breastwork for defence on shore and then, on 22 February, tried again. This time, the Alceste was set alight and destroyed, although some barrels of flour and, mirabile dictu, a case of wine and a cask of ale were retrieved.

On 24 February, some pikes and muskets were also recovered, as the Alceste’s upper works had burned away, revealing what lay beneath. With these, the crew were able to beat off an attack two days later. More pirates arrived in the coming two days, firing on the stockade with carronades from their prows in the cove. By 1 March, there were fourteen of these offshore, with more arriving overnight. By 3 March, the situation appeared desperate, but then the sail of a rescue ship, the Ternate – sent by Amherst from Batavia – was descried on the horizon, and the pirates were driven off by an attack launched by the Alceste’s marines.[19]

Hall tells us that, upon their departure from the Korean coast, in September 1816, the English left without much regret. ‘The venerable chief,’ he wrote, ‘with his snow-white beard, his pompous array, and his amusing and active curiosity, had made a considerable impression upon us all.’ He was good enough to concede this ran to a measure of respect, although he indicated it was tempered by ‘his unmanly distress, from whatever cause it arose.’

The extreme promptitude with which we were met at this remote spot, and the systematic pertinacity with which our landing was opposed, not only on the continent, but even at islands barely in sight of the coast, certainly imply an extraordinary degree of vigilance and jealousy on the part of the government. One can understand this better in China, where the circumstance of a strange ship calling at one of the outports, is a possible, though not a probable, event; and where the government, instead of encouraging foreign trade, are perpetually on the watch to repress all attempts at an extension of foreign intercourse with their Celestial Empire. But in Corea, where there is infinitely less probability of a foreign ship ever calling, the same watch against foreign interference, is far more curious.

The inhabitants, he concluded, were sufficiently unfriendly that there were few grounds for supposing a longer stay would have resulted in a more useful exchange. Hall’s parting advice was to allow plenty of time to overcome the Koreans’ distrust, and ‘to carry along … a person skilled in the Chinese written character, and acquainted with some of the spoken languages of those seas.’ Britain’s next visitor to Korea was not slow to take up the second of his recommendations.[20]

The Voyage of Hugh Hamilton Lindsay (1832)

One unusual feature of the encounters of Broughton and Hall with Korea is that they occurred many years after the British were already familiar with most of the other the peoples of Asia. They had, moreover, been brief. They were confined to the coastal strip. Absent an interpreter, understanding between the two sides had been strictly limited. It is possible that, with more understanding, the humour of those episodes would have been lost. Hugh Hamilton Lyndsay’s account has its moments of humour also but, with improved intercourse, his perspectives run deeper.

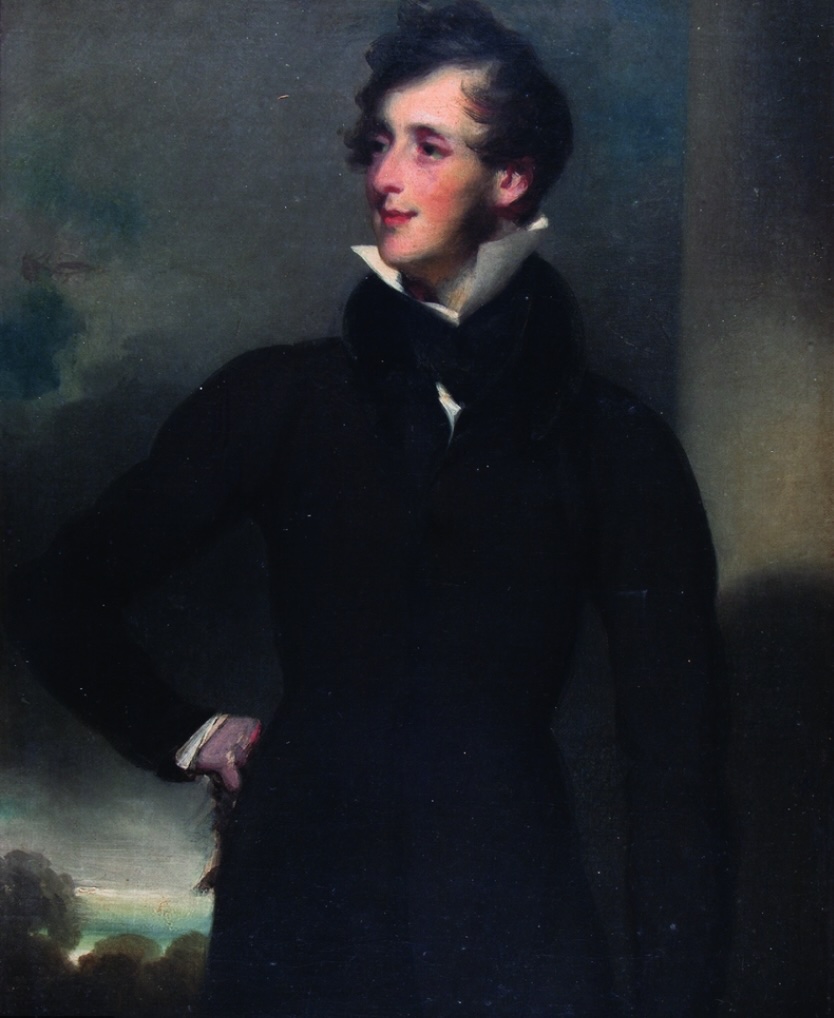

Lindsay arrived in Korea sixteen years after Hall, in 1832. He was a character of a different stamp; in fact, one of those private traders who, over the course of two hundred years, had been a persistent thorn in the side of the East India Company. The nephew of the Earl of Balcarres and the son of one of the Company’s chairmen, he was twenty-nine when Charles Marjoribanks, President of the Select Committee of Supra-Cargoes at Canton, connived with him to organise a voyage to force open the door to the China trade.

Officially, the terms of his commission were:

… to ascertain how far the Northern Ports of China might be gradually opened to British Commerce; which of them was most eligible; and to what extent the disposition of the natives and local governments would be favourable to it.

In addition, Lindsay was told ‘to avoid giving the Chinese any intimation that he was acting in the employ of the East India Company.’[21]

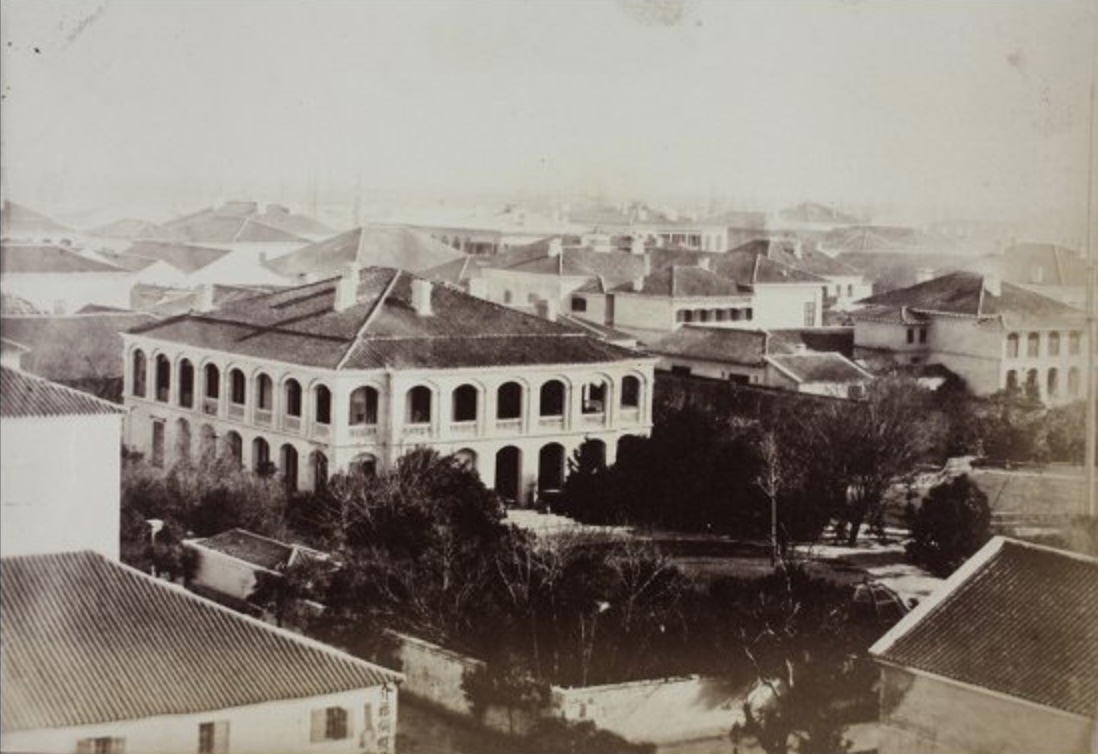

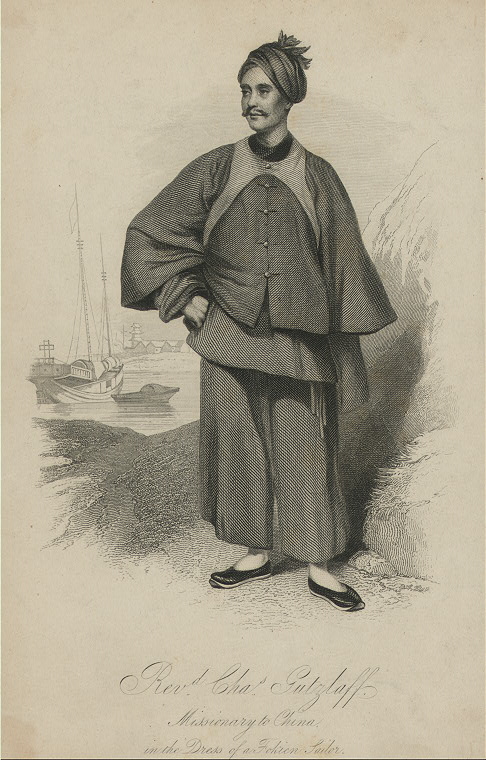

The British community at Canton was small. However, although their movements were restricted, and they were obliged to treat exclusively through Chinese cohong traders, they were in many respects left by the Qing to look after themselves. Those that were willing to play by the rules prospered. (One such, the American William Hunter, of Russell & Co., took $200,000 with him when he left Canton, after eighteen years, in 1842.) Hugh Hamilton Lindsay was not so willing. To him, the restrictions put on the British by the Chinese were an affront to the dignity of his nation. Nor was he prepared to depend on the cohong to get his message across. He determined to do so himself, with the help of his translator, Karl Gutzlaff, a Lutheran missionary who had sailed up the coast before. He took a Chinese printing press, on which he published favourable pamphlets about the British. In short, he was a man with a mission. Lindsay knew that the Company’s monopoly on tea was set to expire in 1833. He was determined to force the pace, to capitalise on the opportunity.[22]

Lindsay was not the only merchant to protest the Company’s pusillanimity in the face of Chinese ‘provocation’. Publications such as the Canton Register were established to broadcast the community’s complaints to the wider population. By way of example, on 6 June 1831, a group of twenty merchants, including William Jardine and James Matheson, posted an article outlining the policies which they judged necessary to deal with ‘a new and objectionable code for the future regulation of the Commerce of Canton.’ Referring to recent events, in which the compound had been ‘attacked’, some property damaged and ‘a gratuitous insult’ offered to the king by the governor, they argued that the Chinese had a deliberate plan to oppress and degrade the British. Their proposals were straightforward:

It [is] advisable to adopt the most decisive steps, if Great Britain wish to retain any beneficial commercial intercourse with China; it being apparent from the whole history of foreign intercourse with this Empire, since Captain Weddell, with a few merchant vessels, in the middle of the seventeenth century, took possession of the BOCCA TIGRIS FORT, till Sir Murray Maxwell, in recent times, silenced the same Fort, by one broad-side from the Alceste; that firmness, resistance, and, even, acts of violence, have always succeeded in producing a spirit of conciliation; while tame submission has only the effect of inducing still further oppression.[23]

At last, Calcutta responded by sending a warship, the Clive, with a letter of protest from the Governor General. When she arrived, the Canton Committee decided to send her along the coast, to transmit his message to Peking. But the ship’s captain refused to accept the quantity of cargo they loaded aboard her, and he returned to India. Thereupon, the country traders chartered a vessel belonging to Cruttenden & Co., coincidentally named Lord Amherst, transhipped goods, and sent Lindsay and Gutzlaff on their way.

They were absent six months, stopping at Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo and Shanghai, before crossing to Korea. Since British ships were not accepted in these ports, they claimed they had come from Bengal and that they had been blown off course.

At Shanghai, Lindsay and his party made it clear they were prepared to use force in order to obtain their hearing:

We landed in front of a large temple, dedicated to the Queen of Heaven, where we subsequently lodged. The crowd opened right and left to give us free admission, and we walked through it into the temple, where a theatrical performance was going on, which our appearance immediately stopped, as everyone’s attention was turned to us. I asked the way to the city and the taoutae’s office, and we proceeded at a rapid pace in the direction indicated.

Inside the city gates, Lindsay was particularly interested to note that many of the shops had on display a choice of European goods. These gave an indication of the potential for trade, but Lindsay was not pleased. After half a mile, he was shown the office of the local magistrate (chih-hien) but, not satisfied, he sought out the governor (daotai), even as an enormous crowd followed in his wake:

… As we approached, the lictors hastily tried to shut the doors, and we were only just in time to prevent it, and pushing them back, entered the outer court of the office. Here we found numerous low police people, but no decent persons, and the three doors leading to the interior were shut and barred as we entered. After waiting a few minutes, and repeatedly knocking at the door, seeing no symptoms of their being opened, Mr. Simpson and Mr. Stephens settled the point by two vigorous charges at the centre gate with their shoulders, which shook them off their hinges, and brought them down with a great clatter, and we made our entrance into the great hall of justice, at the further extremity of which was the state chair and table of the taoutae.[24]

In fact, all along the coast, the British mystery ship had been treated by the Chinese with considerable restraint. She was not seized, and her crew were not imprisoned. They were not attacked. Such violence as there was came from the British side. Lindsay and Gutzlaff obtained interviews with senior officials, and tense though they were, the British were urged to leave rather than threatened with force. How would they be received in Korea?[25]

When, on 17 July 1832, Lindsay first spotted land a little to the north of the Sir James Hall group of islands, his expectations were low. The time spent in China meant there was too little remaining for the extended stay that he believed would be required to overcome Korean antipathy. Nevertheless, he prepared a petition addressed to the king which, he hoped, ‘might perhaps be the means of obtaining a more cordial reception for future visitors.’ In it, he wrote,

[Our] ship is a merchant vessel from Hindostan, a large empire subject to England, which adjoins the south-west frontiers of the Chinese empire. The cargo of the ship consists of broadcloth, camlets, calicoes, watches, telescopes and other goods, which I am desirous to dispose of, receiving in exchange either silver or the produce of the country, and paying the duties according to law.

Although Great Britain is distant many myriads of le from your honourable nation, ‘yet within the four seas all mankind are brethren.’ The Sovereign of our kingdom permits his subjects freely to trade with all the nations of the earth; but our laws expressly command them, in their intercourse with distant kingdoms, invariably to act with honesty, justice, and propriety; thus the bonds of friendship, which unite distant regions, may increase, and the benefits which arise from commercial intercourse may be widely extended.

Hitherto no ships from my nation have visited your honourable kingdom for purposes of trade; but as your Majesty is a wise and enlightened sovereign, whose anxious wish is to promote the welfare of his subjects, it may be a subject worthy of your consideration, whether the revenues of your nation, and the prosperity of its subjects, would not be increased by the encouragement of commerce with foreign countries.[26]

Lindsay’s plan was to take this message as close to the Korean capital as possible, to facilitate its delivery to the palace. If it was received favourably by those he met, he proposed to wait until he received a reply. If not, he judged no harm could result from the experiment.

The next morning, the British party were met by numerous people as they approached a Korean village. Many wore the distinctive, broad-brimmed hats Basil Hall had written of. Prominent in the crowd was one man with a matchlock in his hand, and a lighted match. He motioned Lindsay to sit on a bank and discuss the paper, but Lindsay’s preference, ‘while the friendly feeling of the natives lasted,’ was to push on. This he was unable to do, as the crowd formed itself into a row to bar his progress. In an ensuing ‘conversation’ with village officials, all of it communicated in writing, Lindsay was told to be gone, one man warning that, if he did not instantly depart, soldiers would be sent to decapitate him. Gutzlaff protested, but the crowd – now numbering some two hundred – became obdurate. Lindsay offered presents of some buttons and calico, but these were refused, and the British made a retreat.

In the ensuing days, the weather turned thick, which prevented the British from going ashore. On 23 July, in the vicinity of Basil’s Bay, the Lord Amherst was visited by some villagers, who were shown the ship and entertained on board with wine. This broke the ice, and a reciprocal visit was arranged on land, in which the British were served with spirits and salt fish.

On 24 July, Lindsay was approached by an official, Teng-no, who had a good command of Chinese. He had been sent by a senior mandarin in the neighbourhood to find out what the strange visitors wanted, and to direct them to a safer harbour.

In reply to some of our questions, he stated the name of their capital to be Keng-ke-taou Han-yang. The first three characters, which have hitherto been adopted in all maps as the name of the capital of Corea, appear merely to designate that is the capital town, and the two last, Han-yang, are the name of it … In reply to a question as to the name of his king, he replied, ‘I dare not write his sacred name; he rules over more than 300 cities, he is 43 years of age, and he has sat on the throne 36 years.’

This seems to have been a friendly occasion. Teng-no and his party were entertained for some hours with sweet wine and spirits before they parted. Lindsay noted,

… the Coreans have all a decided partiality to strong liquors, of which they drink considerable quantities without its producing any effect on them.

On 25 July, the Lord Amherst was piloted around the coast to a position of shelter in the lee of some islands. No sooner had her anchor been cast than several boats approached. Teng-no this time was accompanied by another ‘secretary’, Yang-yih, a ‘chief mandarin’, Kin Tajin, and another civil chief, Le Ta-laou-yay. Le was old and infirm but sported a venerable white beard. Kin,

… was a fine old gentleman of 60, who from the first saluted us with perfect frankness and good humour, nor did he ever deviate from this during the whole period of our acquaintance.

Before the questions began, the Koreans repeatedly consoled the British for the hardships they had endured on their journey. Many enquiries were then made regarding the content of Lindsay’s letter, but he was hesitant to give details beyond saying that his purpose was trade, and that he hoped to deliver it, with some presents, on shore that afternoon. Lindsay says,

The novelty of this whole transaction was evidently rather embarrassing to the Corean chiefs; they looked at each other, hesitated, several times dictated to their secretary, stopped him, and finally replied nothing.

There was an exchange of gifts and, before the Koreans departed, Lindsay reiterated his intention of coming ashore. The suggestion, he writes, was accepted by Kin, who greeted it with the remark ‘hota’ (‘good’) and directed his secretaries to remain behind. He continues,

The events of the last two days I confess surprised me considerably, showing the Coreans in so very different a light from what all accounts of former navigators and our experience led us to expect … I therefore considered it incumbent on me to make the most use I could of the present favourable opportunity to remove as far as was in our power the jealous apprehensions of foreigners which the Coreans entertain.

In the circumstances, Lindsay decided to add to the presents he intended for the king. These included cloths of various kinds, two telescopes, some items of glass, and a selection of books – translations of the Bible, tracts on geography, astronomy and the sciences brought by Gutzlaff for the Chinese. On landing, he was therefore surprised to be met by about fifty ‘wild-looking’ Koreans, several of whom used throat-cutting gestures to make it clear they wished the British gone. Yang-yih, who had lost his earlier vivacity, proposed they might return the next day. Lindsay, however, was ‘determined to see the thing fairly out,’ so he took his party straight up to the village:

As we approached we heard the sound of trumpets, and saw two soldiers (who are distinguished by a blue dress, felt hat, with red tuft of hair hanging from it) marching down the lane blowing with all their might. They emerged just as we approached, and keeping close together abreast so as to block the passage, they blew a tremendous blast at us. We stopped and stared with astonishment, but in a half minute we saw the old chief and Kin coming down the lane on open chairs, carried by four bearers. Le was seated on a tiger-skin, and made a most picturesque figure.

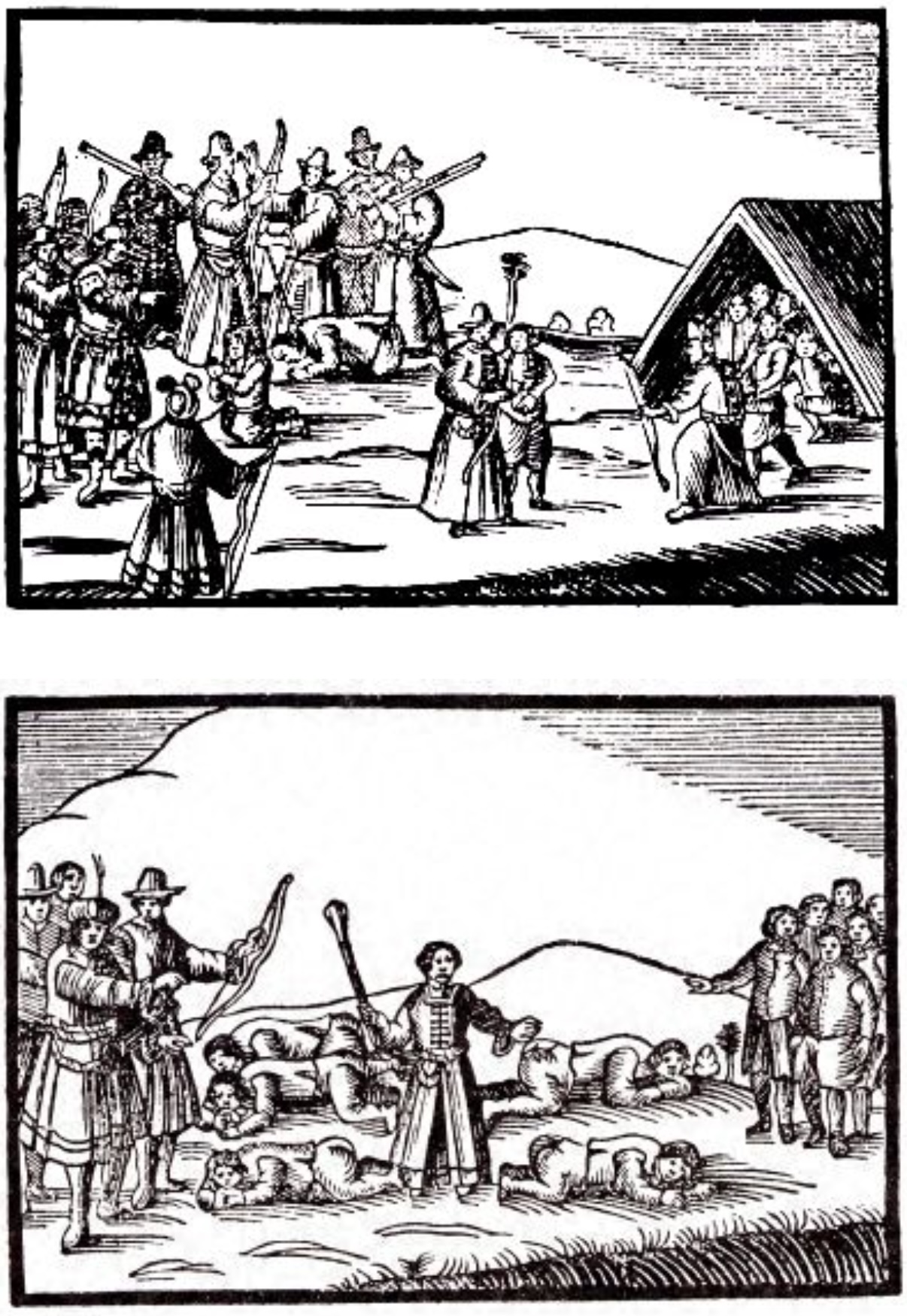

Getting out of their chairs, the chiefs politely pointed to the beach, where a shed was being assembled on poles. This struck Lindsay as not at all fitting for his purpose. Forcing his way ‘without violence’ between some villagers at the entrance of the lane, he picked out a house with a commodious verandah, and entered it. A loud yell went up, and soon, four soldiers were seen running along the beach towards him:

… two of them each seized on a man with a large round hat, which the first took off, and then ran off again, dragging their victim between them as quick as they could run. The chiefs were seated on their chairs on men’s shoulders close to the shed. On the culprits arriving they were first made to kneel before the chiefs and then laid down, and while one man removed their lower garments another brought a long paddle, in readiness to inflict summary punishment …

I could not, however, tamely look on and see perfectly innocent persons punished for my own act, so I went straight to the soldier, who was in the act of striking, and stopping the uplifted blow, motioned him to stand aside; one of the crew, a stout negro, did the same to the other, and as the fellow did not seem inclined so quietly to submit to his authority, he in a moment wrested the paddle out of his hand and threw it to a distance. A crowd of more than 200 people had assembled around the chiefs, who sat raised up among them in their open chairs, and appeared much troubled in mind.

One can imagine the scene. However, the dust settled and, after a palaver in the shed on the beach, it was agreed that discussions, involving Lindsay, Gutzlaff, Simpson and Stephens only, could continue in the village. This time the delegations were preceded by soldiers armed with trumpets, sent ahead ‘probably to see that no women were loitering about.’

In the meanwhile either to pass the time, or to impress us with a due reverence to the Corean laws and chieftains, a poor fellow was pulled forward, laid down, and after old Kin had made him a short harangue, a soldier stepped forward with a long paddle and inflicted his punishment, which, however, was not severe, being only two blows on the posteriors, and not given with much force. About ten fellows howled in concert with the sufferer, which is part of the ceremony. As we conceived that we could have no possible connexion with this case, we quietly looked on; but on inquiring from Yang-yih the cause, he replied, ‘It is for misconduct on public business and disrespect towards you.’ What it was, we had no idea.

In a brief ceremony, followed by a tasting of wine, ‘with raw garlic as a relish,’ Lindsay handed over his presents, and the letter, and obtained a promise that they would be delivered with utmost speed. He then retired to his ship, where he found some gifts of food, a sign, he believed, that he had ‘made some little progress towards a friendly intercourse with this misanthropic race of beings.’ At eight o’clock, Teng-no and Yang-yih reappeared. They had been sent to obtain answers to a series of questions about the ship, her cargo, and Britain. Their conference lasted several hours, Yang-yih, at one point commenting, ‘Except by writing my words are unintelligible to you, and yours to me; truly this is vexatious.’ They departed at midnight.[27]

Over the course of the next several days the conferences continued. Lindsay tells us Kin Tajin’s manners ‘though rough and rather boisterous, were accompanied with so much tact and good humour, that he was soon a general favourite.’ (Le, he decided, was disgustingly coarse and, for him, Kin offered a diplomatic apology.) One afternoon, there was a small expedition in which Gutzlaff showed some villagers how to plant potatoes. On the following day, Lindsay was gratified to see the area in which they had been sown neatly enclosed within a hurdle. When preparations were made for watering the ship on an island opposite, a crowd of several hundred appeared, and cheerfully sang ‘a monotonous song like the Lascars,’ as they passed the buckets down the line.

On 30 July, the British were visited by another chief, evidently of higher rank, and known as ‘the General’. A man of about fifty, distinguished by a fine black beard, slightly silvered, he had dress and manners far superior to any yet seen. He wore a pointed hat, decorated with peacock feathers, and fastened under the chin with beads of amber and black wood. His upper garments were of fine Japanese silk, his flowing white robes spotlessly clean; exceptionally so, even by the standards of the Chinese mandarins. He and the other chiefs brought a Korean dinner for the entire ship’s crew and joined with Lindsay and his officers to eat it at tables arranged on deck. It was judged by all to be very palatable.