Japan’s Toyotomi Hideyoshi had firmer ideas than the Ming about turning Taiwan into a fiefdom. In his Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, of 1609, Antonio de Morga wrote that, in 1596, he had planned to capture it, to use in a strike against Manila. Its Spanish governor heard of the plan and sent two ships …

… to reconnoitre this island and all its ports, and the state in which it was, in order to take possession of it first: or, at least, should there not be means or time for that, to give advice in China … so that they, as ancient enemies of Japan, might prevent their entry into it, which was so injurious to all of them.

This is the first mention of European interest in establishing a presence in Taiwan. As it happened, Hideyoshi died and the Spanish abandoned thoughts of conquest, although they operated a factory at Keelung, from 1626 to 1642.[5]

Hideyoshi’s designs were maintained by his successor, Tokugawa Ieyasu. He attempted to occupy the island twice, in 1609 and 1616. In May 1616, Richard Cocks reported from Hirado that,

… The sonne of Tuan Dono of Langasaque (the governor of Nagasaki) departed to sea with 13 barkes laden with souldiers to take the iland Taccasange, called by them soe, but by us Isla Fermosa.

Cocks had discounted earlier rumours of this expedition, thinking that it was destined for the Ryukus, where Hideyoshi’s son, whom Ieyasu had supplanted, was thought to be lurking. Irrespective, the invaders missed their design. Cocks writes,

One boate of Twans men put into a creek at Iland Fermosa, … but, before they were aware, were set on by the cuntrey people, and, seeing they could not escape, cut their owne bellies because they would not fall into the enemies hands.

The survivors crossed to the mainland, where they seized numerous junks, throwing their crews overboard. 1,200 Chinese were killed.[6]

In the end, it was the Dutch who established themselves in Taiwan. They did so on the rebound, in 1624, after an attack on Macao was repelled, and the Ming drove them out of Penghu (P’eng-hu), the ‘Fishermen’ (Pescadores) islands in the Straits. The Macau enterprise was the idea of Jan Pieterszoon Coen: a plan to engross the Portuguese trade in silk with Japan, to weaken Spain’s grip on the Philippines, and to secure a means of trade with China. Guided by Li Dan (Li Tan), the operator at Hirado of an illegal trading network with China by way of Taiwan, Richard Cocks was impressed by Coen’s idea. Indeed, he recommended that the English should join the effort. ‘The King of China would gladly be ridd of their neighbourhood,’ he wrote of the Portuguese, ‘as our frendes which procure our entry for trade into China tell me.’ After his retreat from Macao to Penghu, the Dutch commander, Martinus Sonck, begged to differ. ‘Our previous actions on the China coast,’ he admitted, ‘have so embittered the whole country against us, that we are universally regarded as nothing but murderers, freebooters and pirates.’[7]

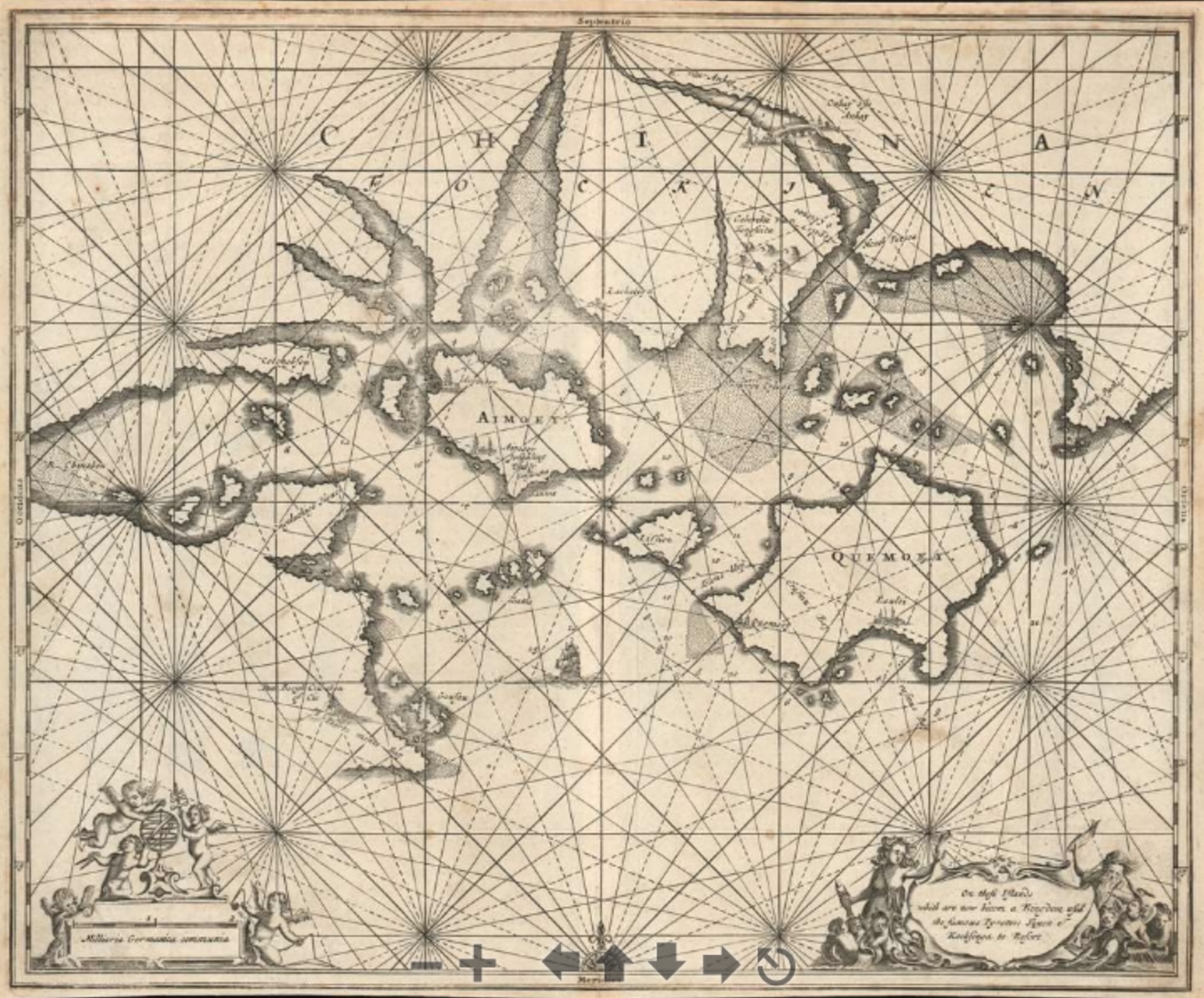

The Fujianese knew that Li Dan was a friend of the Dutch as well as of Richard Cocks. Accordingly, they kidnapped his partner in Amoy (Xiamen) and blackmailed him into telling the Dutch to quit Penghu for Taiwan. Li Dan sent Zheng Zhilong (Cheng Chih-lung), his Fujianese interpreter, with them, to report on their activities.[8]

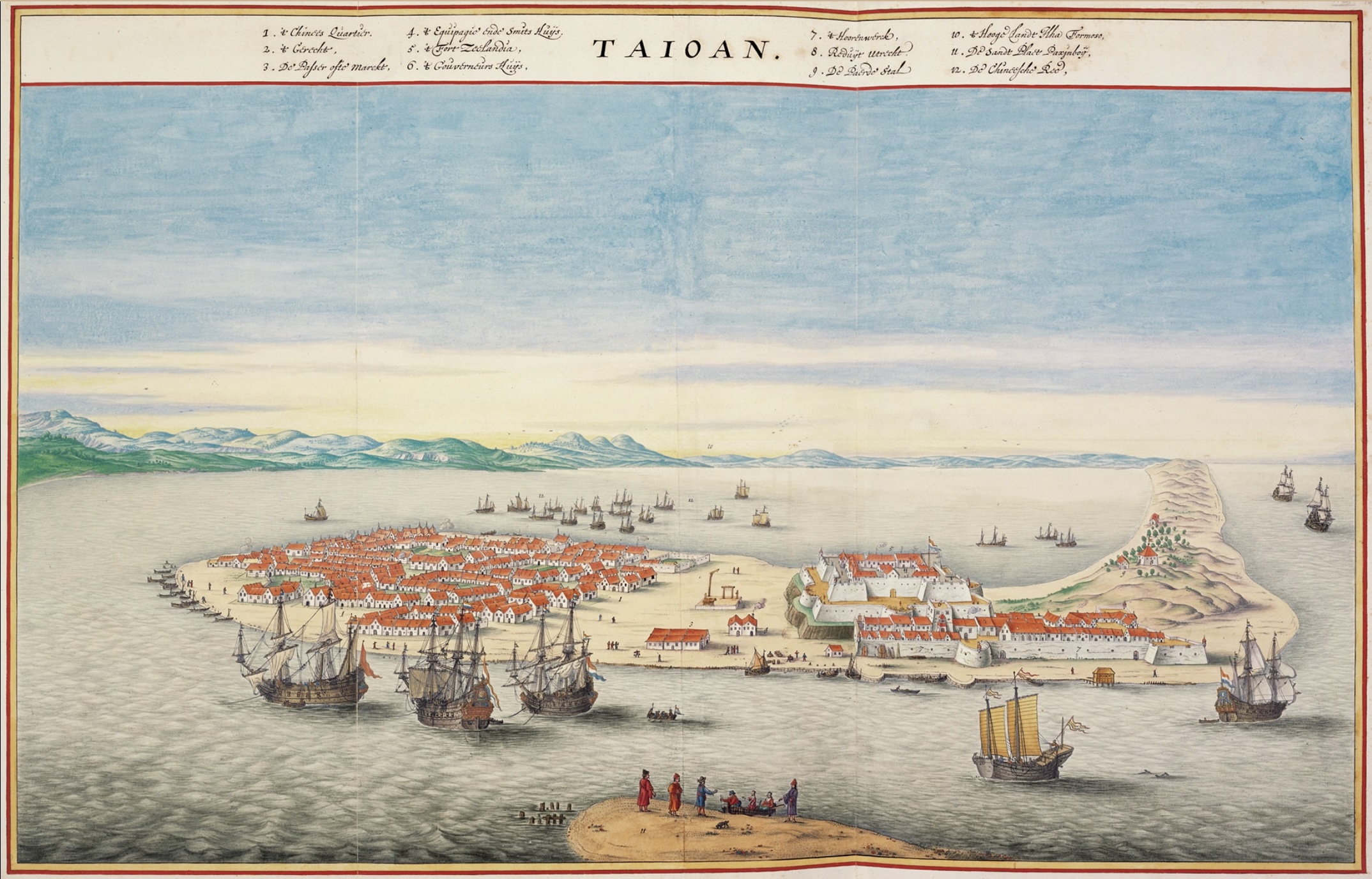

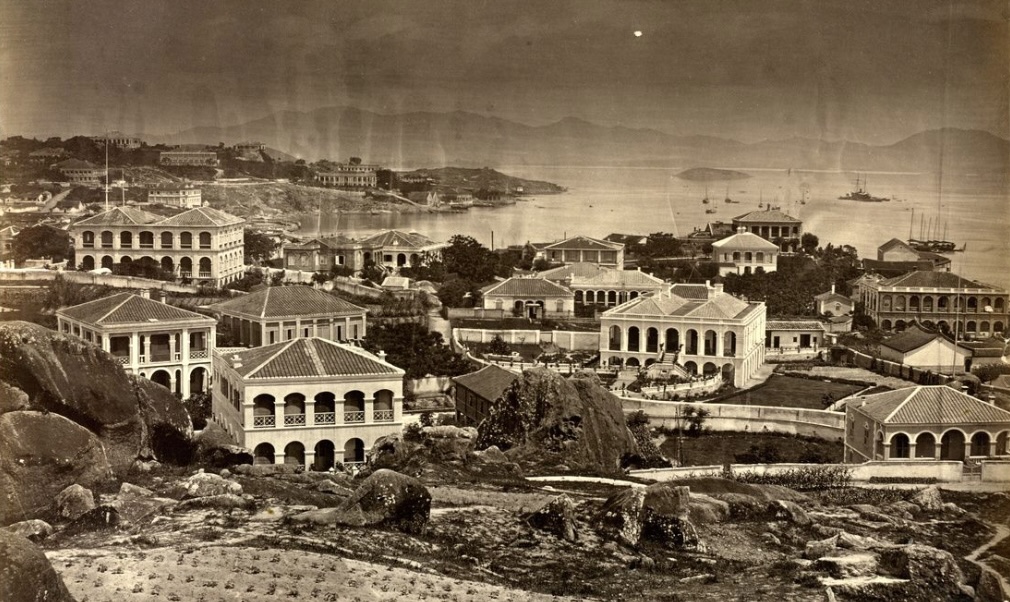

It was not an auspicious beginning, but Fort Zeelandia, the VOC’s factory at Anping (Tainan), became one of its principal establishments. At its heart lay the sale of Chinese silk to Japan. The trade had sustained Macao since the 1550s, and Tainan quickly became an emporium for Japanese and Chinese merchants. Then, in 1635, the shoguns forbade Japanese citizens from travelling abroad. When, in 1639, they expelled the evangelising Portuguese, the Dutch factories at Hirado and Fort Zeelandia filled the void.[9]

Fort Zeelandia thrived. Chinese immigration was encouraged, and with it there developed a significant agricultural economy. But it was exposed to developments on the mainland, where the Ming were faced by the Manchus (Qing). The struggle between them was to involve Taiwan for the next forty years.

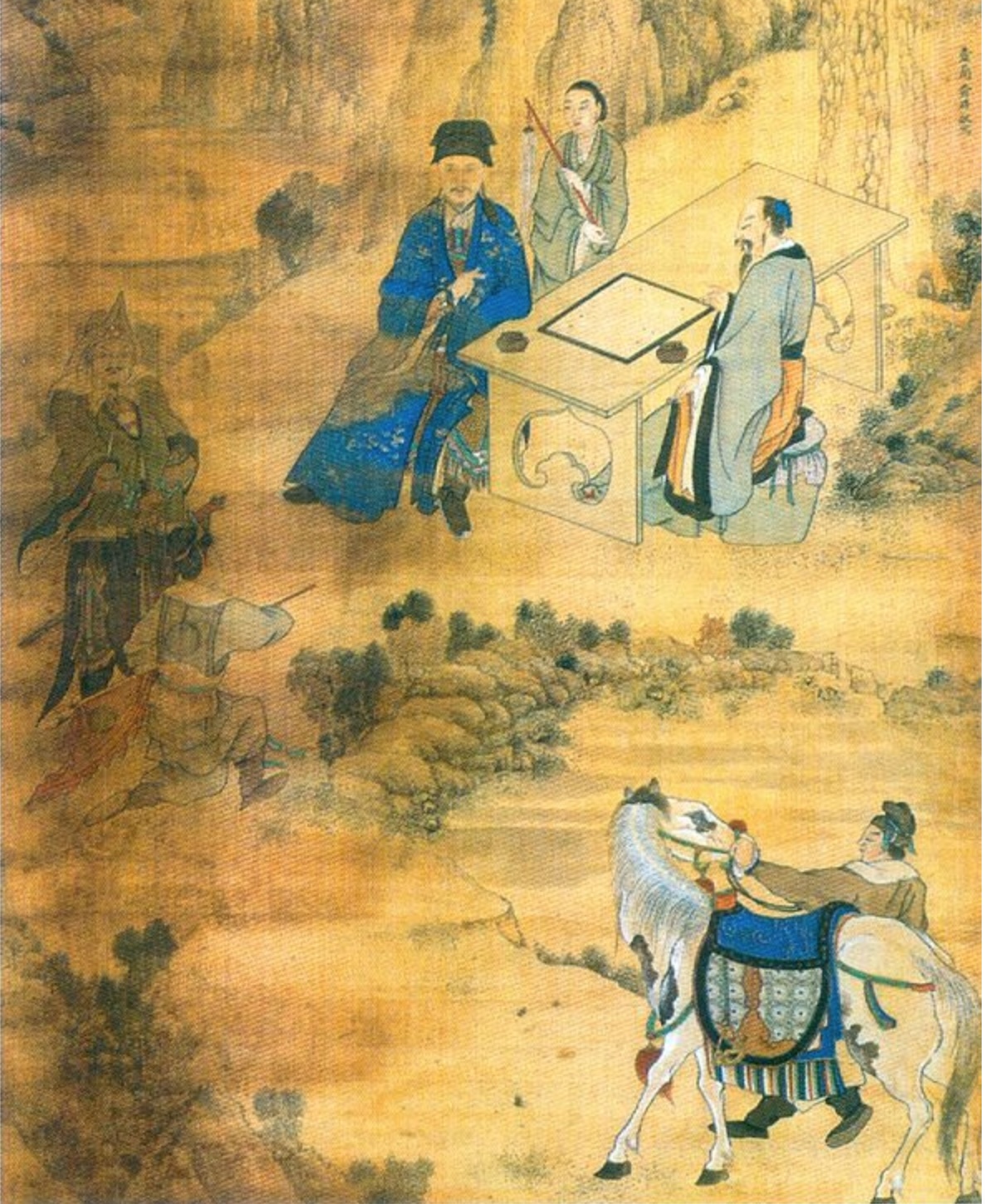

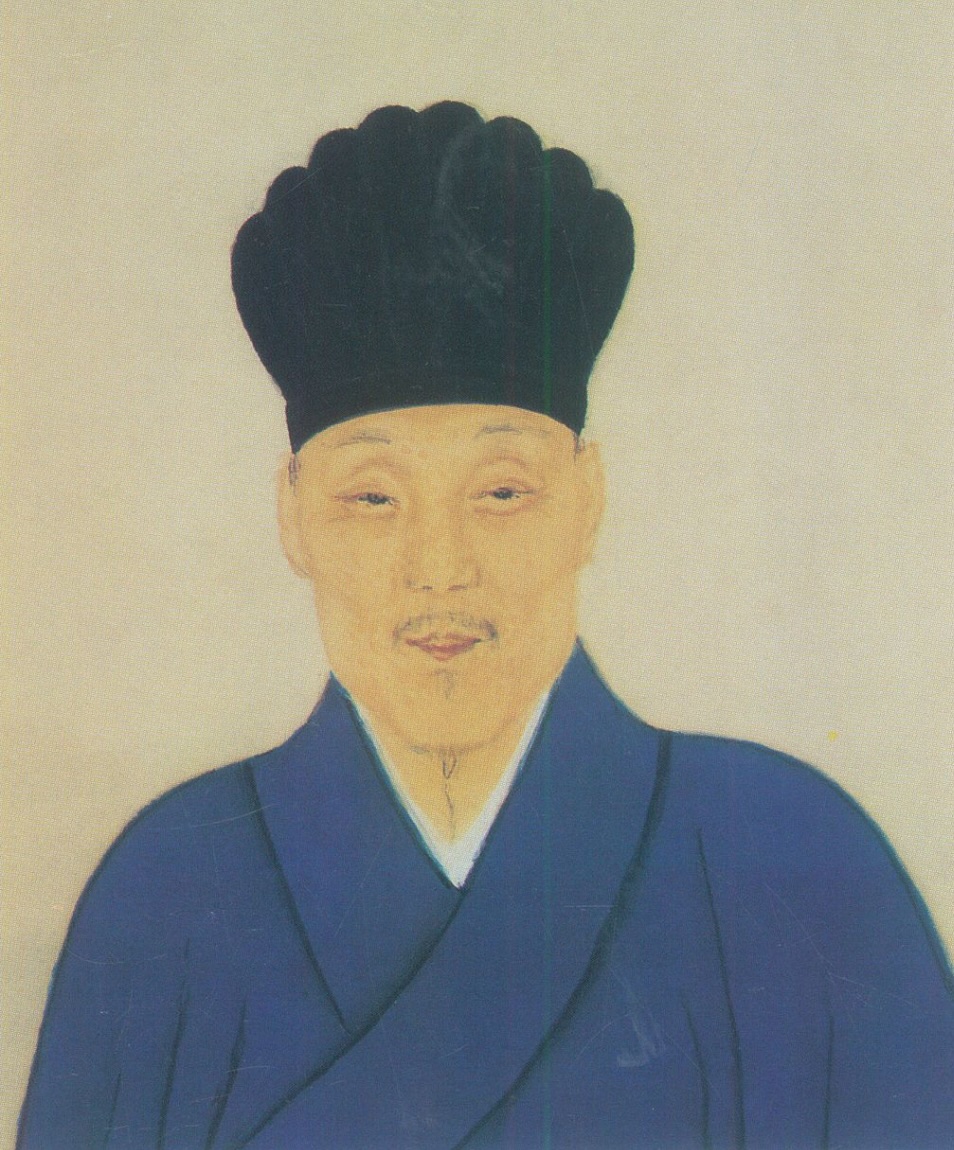

When, in 1644, Peking fell, the provinces opposite the island supported the Southern Ming’s Longwu Emperor, who established himself at Fuzhou (Foochow/Fuchou). Zheng Zhilong, who after Li Dan’s death, and initially with Dutch support, had become pre-eminent among the Chinese trader-pirates, became the Ming’s commander in Fujian. His son, Zheng Chenggong (Cheng Ch’eng-kung), better known as Koxinga (guo xing / ‘Lord of the Imperial Name’), was given the task of suppressing the other pirates on the coast.

In 1646, Longwu was captured and executed. Zheng Zhilong joined the Manchus, but Koxinga remained staunch to the Ming, financing a military campaign through maritime trade centred on Japan. On some estimates, the revenues this generated in the 1650s were greater even than the VOC’s. He was remarkably successful, but defeat in an attack on Nanjing, in 1659, marked the apogee of his power. In 1661, in a move that foreshadowed that of the Kuomintang in 1949, he crossed to Taiwan. The Dutch were driven out of Fort Zeelandia, after a nine-month siege. The news was greeted in Amsterdam with a thirty per cent fall in VOC stock.[10]

Koxinga survived his victory by just a few months, but his regime endured. Nominally it represented the defunct Ming, but in practice it became a family fiefdom, with Koxinga’s son, Zheng Jing (Cheng Ching), at its head. Like his father, Zheng put his trust in overseas trade, and Taiwan remained an important entrepôt. The Manchus, supported by the Dutch, attempted to throttle Taiwan’s commerce using a policy of ‘coastal evacuation’. It was extremely painful for the Chinese population, and only partially successful. Clandestine activity persisted. The Zheng expanded their operations in Southeast Asia, and in Japan, where the shoguns, fearful of the Mongol threat represented by the Manchus, welcomed them.

As Taiwan grew in prosperity, the English East India Company considered whether it might offer a profitable opening.[11]

Henry Dacres Leads the Way (1670-1671)

In April 1670, Henry Dacres, head of the Bantam Council, wrote to Fort St. George to explain that Zheng Jing was inviting people from overseas to visit his country. He understood that London desired trade with China, Japan, and Manila, so, on his own initiative, he sent Ellis Crisp and a Chinese Captain, Sooks (‘Succo’) to investigate.

If reporte answers expectation [he wrote] wee intend the next yeare to endeavour the settling a factory there … This place lyeing soe conveniently in the midst of them, wee hope in a manner [may] prove a magazeene of trade for all those 3 places.[12]

The mission reached Taiwan on 23 June. Sooks presented Zheng Jing with a letter which sought permission for a factory:

Wee are Englishmen [it blazed] & a distinct nation from Hollanders, some people of which nation about ten yeares since were droven out of your land by His Majesty your renowned father … Wee have for these forty yeares had our godongs at Bantam and are more often at varience with the Hollanders then with any other nation whatsoever.[13]

The request was favourably received, and on 10 September, an agreement was negotiated, granting the English the right to export deer skins, sugar and other commodities to Japan, Manila and elsewhere. Goods were to be obtained at market rates. Provided they showed their colours, Company vessels were to be spared molestation by Zheng’s junks. The English could trade with whomever they pleased, there were no restrictions on the goods they could import (an import tax of three per cent was chargeable), and they could freely export gold and silver. For a factory, they were granted the Dutch stadthuis and a new godown, to be rented for five hundred reals a year.

The Zheng regime welcomed the chance to trade with Bantam, to which the English offered access protected against Dutch reprisals. They also had eye for military know-how. According to the agreement, the English were to keep in Taiwan ‘2 gunners for the King’s service for granadoes & other fireworkes,’ and a smith ‘for making the King’s guns.’ Every incoming cargo was to include two hundred barrels of gunpowder and two hundred matchlocks.[14]

Despite his success, Crisp complained vociferously of the underhand behaviour of the ‘very knave’ Sooks, whom he accused of combining with his relations in Taiwan ‘to abuse us in the selling and buying of our goods.’ For his part, Sooks claimed rights over some of the pepper brought in the Bantam, and threatened to make the English odious to all, including the sultan at Bantam, if they were not honoured. Crisp writes,

When wee were selling severall goods to the King’s merchant hee goes & informes him that they were worth but soe much in Bantam & in many things not above ½ what they cost, and they being for the King made him much strange that wee should aske such extravagant prices.

Crisp enjoyed no direct contact with Zheng or his officials. He was dependent on Sooks for his information, and Sooks kept him in the dark. There were other problems. At first, only the king’s representatives were permitted to buy. These rules were relaxed, but prices remained low: large cargoes brought in daily from China were cheaper. After an initial burst of interest, Crisp sold nothing in a month. In addition, Taiwan’s principal exports were reserved for the king. No wonder: they made substantial profits. Deer hides, priced at between sixteen and twenty reals per hundred, sold in Japan for seventy reals, and the uplift on sugar was four times over cost. The king also had a monopoly over sales of copper, which was imported from Japan.

Nor were the signs for selling goods into China propitious. As a result of hostilities, product had to be smuggled in, and steps had been taken to make this difficult. For his pepper, which he sold in Taiwan, Crisp could obtain just seven reals the picul, with the (unenforceable) promise of more, if it met with a good end market. Crisp wrote,

‘Tis a difficult thing to carry into China, as allsoe all such bulkey comodities, for upon all this coast there are forts for to hinder the coming in of all goods. Nay, if any person is found without the wall ‘tis death. What is done is by bribeing. The most they carry from hence is Japons copangs (koban), for ‘tis much less trouble to bring goods out then carry in. It was a greate while ere I would lett the pepper goe on such termes, but I found that those persons that bad for itt were the King’s merchants & noe private man wold by itt, the carrying into China being so difficulte.

Despite these misgivings, Crisp left Taiwan in optimistic mood. Steps could be taken to deal with Sooks’ misdemeanours. More pertinently, the Manchus were proposing a treaty of peace. It promised to make Taiwan ‘a verry considerable place of trade,’ as Zheng Jing plainly intended it should be. He offered to buy any of the Bantam’s goods that were unsold at her departure (possibly most of them), and to waive import tariffs and factory rent for the year.[15]

Bantam took Crisp at his word. The voyage had not answered their expectations, but they reasoned that the market had been temporarily depressed by the pepper seized with Fort Zeelandia, and that the failure of the trans-Pacific voyage to Acapulco meant that Chinese junks intended for Manila had been disappointed in their trade. Henry Dacres wrote,

… the respects of the King &c were great towards us and promise us fair conditions, which … animate us in the prosecution of your future intrest to a second attempt, when we shall totally exclude all China rascalls which were the last yeare forced upon us by these Kings and grandees … The trade at Tywan being yett but an embryo with other nations as well as with us, wee cannot yett give you an encouragement for present supplyes of quicksilver, vermilion or broadcloth, but we believe from Tywan wee may probably find a trade to Japon.[16]

In July 1671, Bantam despatched two ships, the Bantam and the Crown, with the Camel junk, for Taiwan and Nagasaki. The factors were told to expect intrusive treatment in Japan, as the people were ‘barbarous and riggid in their humour.’ Later experience vindicated the advice but, on this occasion, it was not required. The voyage was a disaster. The Bantam and Crown perished at sea before reaching Taiwan.[17]

By the time Bantam heard of their loss, London had news of Crisp’s voyage. For many years after the closure of the Hirado factory, in 1623, the Directors had shown little inclination to repeat the Japanese experiment. Then, in 1658, the Company’s capital was replenished under a new charter, and Quarles Browne, one-time factor in Cambodia, persuaded them to make another attempt. The voyage was abandoned, but Browne persisted, and the idea did not go away. It came to the fore at moments when complaints about exports of bullion were at their loudest, and the Directors were under greatest pressure to find new markets for English manufactures.

Interestingly, in 1633, the Company had responded to the lobbying of Thomas Smithwick with the prescient remark that,

… without the Company can obteyne a trade to China, the trade to Japan will not bee worth the following for that the proffitt which is expected is not by the Comodities to bee sent from England to Japan, but from China to Japan, and soe from thence to the Southwards and home.

One of Browne’s services to the Company was to open its eyes to the possibility that Cambodia, Siam or Tonkin might serve as supply points for Japan. In 1668, a committee was formed to canvass opinion. Richard Bladwell advocated Siam, Peter Cooke who, from Bantam, had observed the activities of Koxinga, Taiwan. The Directors wavered. They desired the trade, but they were wary of new investments.[18]

Finally, in October 1670, they cracked, and the frigate Advance was prepared. The Directors wrote to Henry Dacres to explain that,

… [we] have bin long considring how wee might enter upon the trade of Japon & Formosa and procure lycense from Spaine for the trade of Manilha … And the better to enable you to make a beginning to Formosa & Japan & touch at Cambojah in the way wee have enterteined a new ship of 220 tons called the Advance friggatt … Yet if upon due consideration of this affaire you find it not fitt to attempt as farr as Japon for the present, then endeavour to settle things at Cambojah, Formosa &c, to procure the best trade you can there & the better to prepare for the Japon trade in the future …[19]

The Directors had come, in a fumbling sort of way, towards a plan for the best way of proceeding, but Henry Dacres had beaten them to it.[20]

The Voyage of the Return, Experiment and Zant (1671-1673)

In April 1671, the Directors announced that they would send two ships for Japan. The departure of the Advance had been delayed, so they asked Dacres to prepare cargoes in Taiwan and Tonkin for this effort instead. (Cambodia was deemed too much a ‘turbulent disordred place’ to serve.) When, in June, they received notice of Bantam’s earlier despatch of the Bantam and Pearl, they were not displeased.[21]

In September, Ellis Crisp’s draft agreement reached London, with confirmation of the successor voyage. The Directors gave their broad approval, but criticised Bantam’s council for being uncommunicative. They suspected private trade. In February 1672, after reading the books for the earlier voyage, they declared they had found ‘very little incouragement’ in it. The ships had been fully laden out and back, and less than a quarter of the cargo had been theirs. They added,

Wee understand that you intended to lay aside Mr Crispe for his miscarriages in the former voyadge, but yet wee find you have againe imployed him therein. If wee have noe bettere satisfaction from our Agent & him &c then hitherto wee have had wee shall call them and others home to give accompt of their proceeding, these actings being soe gross as not to be endured, as wee are well assured, they haveing made great advantage by that voyadge.

They were not to have the satisfaction. Ellis Crisp perished with the Bantam.[22]

In September 1671, the Return, Experiment and Zant departed London. Two ships had become three. They were intended for Tonkin, Taiwan, and Japan, to establish factories in each. The principal intention was to sell English cloth to the ill-clad Japanese: Surat’s president had advised that they dressed only in ‘oyld paper & such like trash.’ Cloth was to be exchanged for gold, silver, and copper, which was to be used by the factories in India and, to a limited extent, Tonkin. For Japan, Taiwan was to supply deer hides and sugar. Tonkin’s contribution was to be musk, silks and tutenague (an alloy of copper and zinc). For trial in India or Europe, Taiwan was also to supply five hundred piculs of ‘China rootes’, sugar (to be used as ballast, or ‘kintlage’), and a selection of large Chinese pots, which were to be filled with ginger.[23]

The structure of the voyage, and the instructions sent to Bantam to collect appropriate cargoes at Surat and the Coromandel Coast, show that London was waking up to the interdependence of Asian markets. But their expectations for woollens demand were unrealistic. The Directors also had high hopes for products sourced in Taiwan. Referring to Bantam’s advice that the Zheng collected 200,000 deer skins and fifty thousand piculs of sugar annually, they indicated that they would contract for it all, were prices less uncertain, and the tonnage not so great. It might delay the onward voyage. Instead, they gave Bantam approval to lade an extra two to three junks for Japan, if the rates were not so high as to ‘eate out the proffitt.’

London also proposed adjustments to Crisp’s agreement. At greatest issue were the clauses connected to armaments and gunpowder. Requiring that these be removed from Company vessels in harbour was judged a dishonour, as it suggested the English were other than peaceful. It also risked delays. Technically, the provision of weapons would breach a treaty between King Charles and the Dutch, as the Zheng were hostile to them, and England and Holland were not (yet) at war. Yet the Directors appreciated the way that Dutch relations were headed. They explained that powder transported from Europe would be expensive and might not arrive in the best condition, but if the Zheng were willing to pay such prices ‘as may be encouraging,’ they were willing to accommodate them. This attitude to the treaty was repaid, in full, on the return journey.[24]

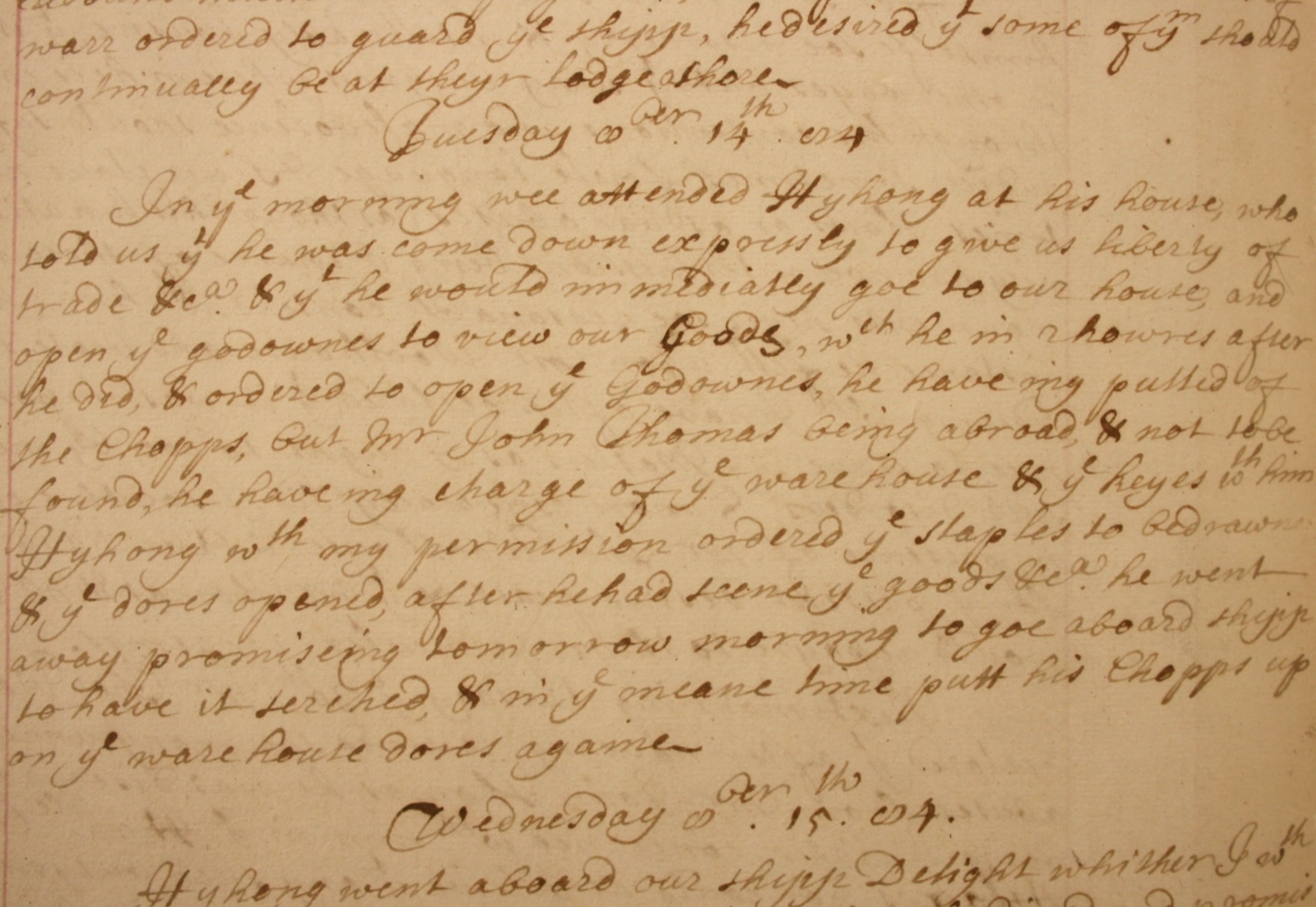

The Experiment and Return left Bantam for Taiwan in June 1672, with the Camel. In Crisp’s absence, Simon Delboe was appointed to head the factory, with John Dacres (Henry’s son) as his deputy. They reached Tainan on 16 July. (The Zant sailed directly for Tonkin.) The factors took with them a letter ‘to encrease the friendshipp already begunne,’ and a warning to be realistic in their expectations. Trade with Japan was important to the Zheng: they would be cautious in sharing it with the English. Bantam added the admonition that the Taiwanese were be treated with care:

Keepe for example before your eyes the transactions of the Chinesees upon the coast of China and examine well how they att all times have behaved themselves towards forraine traders, and you will finde that all their practizes have been sinister and false and their dealings by all have beene proved cheates. And [for] further knowledge compare the old Chineses of China to the Tywanners and you will finde them to bee still one & the same with their lives, manner, humour & inclinations …[25]

Bantam hoped a turnaround might be accomplished in six to eight days, which was highly optimistic. Zheng Jing gave the fleet a splendid reception, but aside from the gunpowder and muskets, which sold briskly, and for high prices, demand was sluggish. A storm obliged the Experiment and Return to shelter in Penghu. Lading and unlading became difficult. Worse, the Camel was caught at the bar at the harbour’s entrance ‘and almost buryed in the sand.’ Most of the goods aboard her were lost or spoiled. In the same storm, a Dutch ship, the Culemburg, was wrecked off Keelang. Her cargo fell prey to the ‘devouring harpies’ of the district and, when it reached Fort Zeelandia, it had a depressing effect on prices.

Delboe informed Bantam that, if he had taken cloth in brighter colours, he might have sold more, but the market for calicoes was oversupplied with cheaper like-product from China. They were purchased in large quantities for onward sale in Manila, which might prove a good market for Indian goods, if a licence could be obtained from the Spanish, and reliable traders identified. In the meantime, he wrote,

… to trade from hence we see no possibility with security, for theis Chineses are not to be trusted, being such excessive gamesters and vitious people that nothing can be expected from them that once they have in their possession, & them of the Manilhas never stirr out of their owne countrey to theis parts.

There were other challenges. The agreement with the Zheng had been adapted to assure the Company a third of the country’s production of hides and sugar, but the number of hides was half that estimated earlier, and sugar output had fallen by more than three quarters since the time of the Dutch. ‘This Kinge,’ Delboe wrote, ‘doth not incourage the people as they did’: the land was ‘being manured for rice & other necessaryes for the poore.’ The bulk of sales were done on credit, obtaining payment took time and, since the expedition carried little cash, it became tight. (Fortunately, the factor David Stephens had died on the outward voyage: Delboe drew on the Rs.2,619 he had taken for private trade.) As it was, the supply of commodities was fitful, their quality indifferent:

The copper was represented to us as cabessa (highest quality) before that we saw it and they demanded 15 3/4 Rs. per chest, whereunto (because being the Kinge’s we could not dispute it) wee did consent but afterwards opening some chests & breaking severall barrs wee discovered it to be no better than pee, or more properly a sort of refuze, upon which making our complaint they lowred the price to 15 Rs per chest.

The regime’s purpose was to foist onto the English products they could not sell elsewhere. And, if the discount appears trivial, there was an explanation. To complain would have made adversaries of the trade’s arbiters. The factors may have been promised free trade, but they were ‘surrounded on all sides with an excessive & intollerable monopoly.’

When he came away on the Experiment, William Limbrey was not optimistic. He wrote,

The people are generally poore & discontented, kept in subjection by a high hand. They came here with a numerous army only with swords in their hands to conquer and mouthes to devoure other men’s labours, which has occasioned all provisions to be very deare. But time may mend this. The King is the only marchant & hath monopolized the goods of the country … which is the best prop of his kingdome … Soe that there is little hopes of sharing with him in theis comodityes although I understood before our coming away that he had by articles promised a third part of them to your Worships at price currant. But the generall terme makes it a dubious contract and such is the treachery & baseness of theis Chineses that I feare this agreement will evaporate & come to nothing.

Limbrey took with him a report prepared by Delboe. Sales to mid-November had been Rs.7,302, 37d. only, and the cost of the Camel’s lost cargo Rs.18,279, 48d. Since the supply of goods suited to Japan was limited, the Return was being sent on alone. The goods collected for Bantam – the copper ‘refuze’, some ‘China rootes’, musk, alum, tea, damask and silk – were inconsiderable.

Three months later, Delboe wrote that there had been no further sales worth mentioning. The Taiwanese demanded goods they knew the English could not supply, and stayed their purchases of those things which they knew they might. There was nothing to buy, except hides and sugar, and then only if the king stuck to the agreement, which was uncertain, ‘by reason of the mutability of theis people.’ Trade with Johor, Patani, Borneo, Siam, and Indochina had fallen away since the days of the Dutch; likewise, that with China, for now the Zheng had only a few toeholds on the mainland, as at Amoy and Quemoy (Kinmen):

It is there where the doore is open to violence, theft & murder, & theis people corrupt the Tartar governors to carry on their stolen trade, comeing by night & at unseasonable times, upon fortfeiture of goods & life, sheltring themselves under pretence of Tartars, which may continue till the Emperor doth disturbe them. This difficulty of trade is the reason the China goods are deare here & ours will not sell. It were strange else that so little woollen manufactures as we have cannot be sold in a country where there is 70 millions of people who are all used to weare a broad girdle of cloth and knee-bands also.

Delboe was critical of Zheng policy. The regime depended on silver from Manila and Japan, yet they had attacked the Philippines just nine years before, and now they were mistrusted by the Spanish ‘for falsity & cheating.’ Their habit of attacking Japanese ships and murdering their crews was pregnant with risk because, as the enemies of the Dutch, they would be undone if they lost Japanese protection.

On the positive side of the scale, a better understanding of Taiwanese demand would improve the preparation of future visits. Delboe hoped for significant profits from sale of hides and sugar in Japan, from copper, which was much in demand in India, and from Japanese koban coins, which could be obtained for 5½ reals, and were worth 8¼ reals in Bantam and 10 reals on the Coromandel Coast.[26]

In the event, neither the Experiment nor the Camel made it to Bantam. They were captured by the Dutch, the first at the Straits of Banca, in December, the second off Bantam itself, the following March. The Return sailed for Nagasaki in June 1673, with Delboe in the place of Stephens. The Dutch frustrated his purpose. They told the shogun that Charles II’s queen, Catherine of Braganza, was the daughter of the Catholic King of Portugal and that trade with the English should be prohibited on religious grounds.[27]

1674-1677: Henry Dacres Shifts the Focus from Japan to China

Even so, the Taiwan factory remained open, with John Dacres, Edward Barwell and Samuel Griffiths as factors. Yet, Bantam’s reasons for retaining it did not match London’s purpose. Henry Dacres believed that trade with Japan was hopeless. (He argued for Tonkin’s closure.) The Directors were unpersuaded. They argued that delays in despatching the fleet from Bantam had caused it to miss the best cargoes for Japan, and had given the Dutch time to work their influence. They indicated that the sultan of Bantam and Zheng Jing should be persuaded to work on the shogun and repair ‘the miscarriage’. The factors were permitted to explore such opportunities as might exist between Taiwan and China, but their principal task was to ‘endeavour by that King’s means to produce our trading to Japan.’ Taiwan would be ‘the magazine till we can get access directly.’[28]

Henry Dacres agreed that Taiwan had a future. But not with Japan. In October 1674, he wrote,

When the Experiment & Returne were at Tywan our eyes were only upon a trade to be drove by shiping to Japon, which now seemes frustrate … Yet we thinke it very probable that by a factory in Tywan, being scituate where Tonqueene, Macaow, Manilha & Japon lye round about it, some considerable advantage may be found out at one tyme or other.[29]

Dacres had not mentioned China by name, but just a few weeks later, he received news of a rebellion on the mainland. The War of the Three Feudatories began when Wu Sangui (San-kuei), the Ming general whose defection to the Manchus had been instrumental in the capture of Peking, threw off his allegiance and struck into Hunan from Yunnan. Shortly afterwards, Geng Jingzhong (Keng Ching-chung), the ruler of Fujian, joined him. Geng had been hesitant, but Wu brokered an arrangement whereby, in exchange for ships and bases at Zangzhou (Changchou), Quanzhou (Chinchew) and Putian (Xinghua), Zheng Jing gave Geng naval support. In April 1674, Zheng moved his headquarters to Amoy, and Geng launched an offensive towards the Yangtze. In December 1674, Dacres reported that Wu had taken over ten Chinese provinces. The situation promised openings for the Taiwan factory:

It is expected from the good comportment of Mr John Dacres & the rest of the English there that they may with much facillity be admitted trade at Huckhew (Fuzhou/Fuchou/Foochow) or Ainam (Amoy) & also have a deede of gift for some part of Tywan, nay, the report goes of the whole island Formosa if they would undertake to keepe it.[30]

When Dacres’ report reached London, in November 1675, the Directors expressed cautious approval. To them, the most pressing target remained Japan, but if Fuzhou and Amoy showed the potential to be profitable, they were willing to treat with them. As to the possibility of being granted all or part of the island of Taiwan, it was a matter which deserved serious consideration:

We do not hereby wave or slight it, nor would we have you do soe, for if any such overtures should be made by the Kinge upon such tearmes as we my close with it with honour, safety & advantage, it is very probable we should embrace it, & therefore would have you receave all notions that may tend thereunto & give us all full & speedy advizes with your opinions thereupon.[31]

The Directors’ opinion was conveyed to Bantam on the Formosa, but Henry Dacres had already acted. In May 1675, the Flying Eagle was despatched for Taiwan. She arrived in July, two years after the Return had departed. Business was poor. The disturbances in China had brought trade there to a virtual halt. In 1675, the Zheng sent nine junks to Japan (one foundered), but the suggestion that they take some English cloth was refused. They claimed they feared the consequences ‘because of our (the English) not reception theire.’ In Taiwan, stocks of unsold cloth were sufficient to last several years. There were difficulties with customs duties and with the collection of debts. The senior mandarins were the worse payers: they had the wherewithal, but officials lacked the will to remind them of their duty. On this Bantam was asked to intervene.

Respecting return goods, copper was in short supply. It was being prioritised for the manufacture of brass guns and the coins being circulated in Zheng’s newly conquered territories. Meagre also was the supply of Japanese koban and sugar. John Dacres wrote,

By the inclosed papers you will see how they have dealt with us about the suger. When they saw the ship (their foundered junk) falling downe, then they came and proffered us a quantity thinking wee would be contented with anythinge they promised us, as wee then insisted on to have the cabesa, but when went to weigh it found it no other than burega. Had it not been to shew you what you may expect another time wee had not sent this but for a sample.

Yet, Henry Dacres’ initiative brought a prize. The Flying Eagle took in her hold, alongside a puncheon of beer for the factors, eleven chests of muskets and three hundred barrels of powder. They were well received. Twice before, the factors had been asked to send men across the Strait to train Zheng forces in the use of cannon. John Dacres had resisted, but the Zheng were now heavily engaged before Zhangzhou, and they feared the consequences if it were not carried. To win John over, officials announced that the Eagle might cross to Amoy to trade. John feared she would be pressed into service, so he referred the matter to Bantam, but he gave the Zheng the use of a gunner for two months. As a result, when the Eagle departed for Bantam, she carried chops giving the Company the right to trade at Amoy in 1676, and a promise that the privilege would be extended to Fuzhou the following year.[32]

Henry Dacres judged this highly satisfactory. In May 1676, he pressed his son to secure the chop for Fuzhou and he sent an unusually large cargo in the Formosa and Advice, to exploit the opportunity.

The Company [he wrote] are angry that their trade is not more enlarged. And whereas Tywan is noe better then as it were a garrison we suppose the greatest buisinese will be at Emoy.

The decision was vindicated by events. A cargo worth £5,000 was sent to the mainland and it realised a profit of fifty-five per cent.[33]

One now gets a sense of a spreading appreciation of China’s potential. The first sign is the expression, given by Surat, in a letter to London from March 1677, to their hope ‘of a faire and rich trade to China hereafter, equall if not better than that to Japan.’ It was not yet London’s expectation, but requests that a hundred dollars-worth of Chinese tea, and quantities of its satin, damask, and silk be sent to London were straws in the wind.[34]

The first indication of support in London for a factory in Amoy appears in the Court Minutes for 13 July 1677. The Directors resolved to send a cargo of cloth, lead and armaments, including ‘2 mortar peeces with some granado shells,’ to ‘the factories in China, viz. Tywan, Amoy and Tonquin,’ and to have ‘four factors & four writers for Amoy etc.’ Again, Asia was ahead of London. On 4 August 1677, comfortably before London’s desire can have been known, Taiwan sent the Advice with a cargo ‘for the port of Eymoy … consigned to Edward Barwell Cheife &ca factors there.’ A month later, the Formosa was despatched from Amoy by Barwell with a cargo of reals and lead. A Company factory had been established on the mainland well before London’s advice was received.[35]

1677-1680: The Factory at Amoy

In October 1677, London sent Benjamin Delaune and George Gosfright as factors to Amoy, with 28,000 rials of goods. Closure of the Taiwan factory was judged premature, but it was subordinated to the mainland. The minutes for 31 August 1677 speak of retaining a skeleton staff, at least until affairs at Amoy had settled and it was known that closure would not cause offence. Likewise, in October London referred to Bantam’s suggestions for factories at Fuzhou, Quanzhou and Canton (Guangzhou), by questioning whether they might operate ‘without prejudice to our trade at Amoy or discontent to the King of Tywan.’

They did not know that, already, Zheng Jing was under acute pressure. On 2 November, Edward Barwell wrote from Amoy contrasting the situation with that of a year earlier. Then, Zheng had ‘severall statly & strong citties & an army … of near two hundred thousand soldiers to defend them.’ Now, all these were lost and ‘his dominions (excepting his kingdome of Formosa) confined within the circle of this and some other adjacent islands.’ [36]

The war had started well. In 1676, after a standoff with Zheng and Wu Sangui, Shang Kexi, the feudatory of Guangdong, stood down in favour of his son, Shang Zhixin. Zhixin signalled his commitment to the cause by granting to Zheng much of his territory east of Canton. Later, the commander of Changting (Tingchou), in western Fujian, who owed allegiance to Geng Jingzhong, surrendered his outpost to Zheng also. When Geng surrendered Fuzhou to the Manchus, at the end of the year, more of his commanders deserted him. Zheng’s territory reached as far as Xinghua, on the southern approaches to the provincial capital. Yet now he faced the full might of the Manchus. In January 1677, he suffered a heavy defeat at the Wulong River, before Fuzhou. By the end of March, Changting, Quanzhou, and Zhangzhou had all been abandoned. In April, Shang Zhixin himself submitted. He was followed, in July, by Zheng’s commander in eastern Guangdong.

In his letter, Barwell makes no mention of the events before Fuzhou, or of the fracturing of the coalition between the feudatories. Instead, he refers to ‘a small defeat’ at Changting (‘Tenchun’), which caused discontent to spread through Zheng’s poorly paid army. In less than a month, it broke into open rebellion. After Zheng abandoned Zhangzhou (‘Chinagchue’), the Manchus absorbed his conquests at leisure. Zheng ‘absconded himselfe amongst his jonks’ until the tumult subsided. Then he removed himself to Amoy. Trade collapsed, as passages to the island were narrowly watched, and everything depended on smuggling. As goods lay unsold in his customers’ hands, Barwell pronounced himself ‘timerous to advise for any goods to this place.’ Yet, the factories at Amoy and Taiwan were kept well-supplied. Two ships were sent in each of the following two years, even though receipt of payment was desultory, the supply of copper fitful, trade with Japan elusive, and arguments over customs levies frequent.[37]

And yet, after pushing the Zheng onto Amoy and neighbouring Quemoy, the Manchus did not press their advantage. Defeating the Zheng on land was one thing, worsting them on their element quite another. It would take time to equip and train the forces required. They therefore opened negotiations, seeking to drive a wedge between Zheng and Wu Sangui. The talks continued, off and on, into 1679. The Manchus offered Taiwan in perpetuity to the Zheng, provided they left the mainland and shaved their heads for the queue of China’s conquerors. Later, even this requirement was dropped: Taiwan might have received tributary status, like Korea. But Zheng Jing demanded Amoy and Quemoy as bases, and Haicheng, on the mainland, as a kind of free trade zone under joint administration. This was too much. The emperor had once said that Taiwan was as valuable to him as ‘a ball of mud,’ but Haicheng was indubitably part of his demesne. ‘Every inch of land belongs to our Emperor,’ argued Yao Qisheng (Ch’i-sheng), the governor of Fujian. ‘Who dares to convert an integral territory of this realm into a jointly ruled zone?’

For a while, Zheng fortunes improved. In March 1678, Edward Barwell expressed hopes of their retaking Haicheng or Zhangzhou and, at the end of April, he reported a victory, in which a Manchu force of a thousand horse and two thousand foot were ‘wholy routed’. Zheng’s new army commander, Liu Guoxuan (Kuo-hsuan), a veteran of the capture of Fort Zeelandia, met with numerous successes. His forces were augmented by the ‘White-headed Bandits’ of Cai Yin, a soothsayer and martial artist, who claimed to be a missing son of the last Ming emperor. In June, they invested Haicheng, which fell with thirty thousand defenders, after a siege of eighty-three days. The victory coincided with Benjamin Delaune’s arrival at Amoy. On 12 October 1678, he wrote that Zheng was ‘in a faire way to recover his lost honour.’ It betokened ‘a considerable trade into the country.’[38]

Yet all was not well. Earlier that year, as the contending armies faced each other outside Shima in Fujian, one of Zheng’s commanders was discovered plotting to admit Manchu troops into his lines. A few weeks later, some of Zheng’s troops were caught on the point of defecting to the enemy.[39]

Throughout, Barwell had been guarded in his views about the war. Delaune was more sanguine. After he died, in September 1679, his body consumed by disease ‘to a meere anatomie,’ the factory’s reports reverted to type. Addressing Bantam’s complaints about Amoy’s unsatisfactory cargoes, Barwell explained there was little that he could do,

… for now … wee have our trade more intreagued and confined than ever before, it being wholly to pass through Sinckoe’s hands, all others being prohibited by the King’s chop put up at our doore to buy or sell with us without his leave.

‘Sincoe’ was Zheng Jing’s agent in Amoy. To counter his obstruction, George Gosfright begged his counterpart in Taiwan to intervene. He was unsuccessful. Most of the copper delivered from Taiwan to Amoy was being abstracted by Sincoe ‘for making of great guns.’

When, in November 1679, the Return sailed for Surat, her lading fell far short of expectations. Yet, at her arrival, in the godown there had been ‘neere two thousand tayle of the last yeare’s stock in ready cash.’ As Barwell explained, assembling a cargo had been a trial, ‘for wee are not at liberty to buy what wee please but are forced to take what wee can get.’ The Manchus’ coastal evacuation policy, and losses of territory on the mainland, were pressuring Cheng supplies. The sugar being sent with the Return was of the best quality, but Barwell warned,

… wee could not possibly comply with your desires in putting it into chests, the country not affording boards to doe it, for the like scarcity of them & of all things necessary for the support of humane life hath not been knowne before in this place, which is occasioned by the vigilant eye of the Tartars to keepe all supplyes from them.

He goes on to explain,

The affairs of the King’s are in a very dubious & unsettled condition, having no small game to play to defend themselves against the Tartars, who continually allarrams them, & his own treasure being expended hee dayly presses of his subjects for supply & all hee can rayse is not sufficient to satisfie his armie, who are much dissatisfied, that wee are not only in danger of the enemy but of insurrections amongst his owne souldiors for want to pay.[40]

London was not yet aware of these developments. It hoped that Amoy would become a considerable market for English manufactures, ‘it appertaining to a great & rich kingdome,’ as well as ‘by having soe near a correspondence with Japon.’ (Evidently, China’s importance had risen, even if it had not completely supplanted Japan’s.) Amoy, certainly, was still seen as more strategic than Taiwan. Indeed, Bantam had recommended that Taiwan be closed ‘for the present’ and, in November 1679, their advice was endorsed by the Directors. With one equivocation: until peace was secured, a factor should remain to collect outstanding debts and maintain a presence just in case Amoy had to be abandoned. This advice was wise.

In February 1680, Bantam reported that a Manchu embassy had been soliciting the Dutch there for twenty ships to be used against Amoy. Francis Bowyear was unsure of the Dutch response, but he noted that one vessel, with a cargo worth 100,000 reals, had been detained by the Manchus the previous year. He believed the Dutch had not been better treated since, ‘which is done in hope thereby to persuade or force them to a compliance.’ In fact, they had become disillusioned with ‘Tartar perfidy’, and they refused to co-operate. Even so, in March 1680, Amoy fell to the Manchus.[41]

1680: Amoy Evacuated

In December, Edward Barwell wrote to Bantam,

…[with] a most unhappy overture to acquaint you with, such as indeed hath quite ruined all our Honourable Masters’ great hopes & expectations of the China trade, being of no less consequence then the total subvertion of their factory in Eymoy and the loss of the whole island to this King & his interest …

On 6 March 1680, a revitalised Manchu fleet engaged and defeated the Zheng at the island of Pingtan (Haitan). Another defeat followed off Chongwu, the peninsula which projects into the Taiwan Strait east of Quanzhou. The way to Amoy was open. On 8 March, as the enemy fired the houses on the coast opposite, Zheng Jing arrested his senior commander, Shi Hai (Shih Hai). Thomas Woolhouse wrote that, after Shi’s defection from the Ming in 1674, Zheng had been induced by his ‘honey words & smooth allurements’ to advance him ‘to that verie height as did only in the throne excel him.’ Now he,

… had brought his most ungratefull treacherous designe to such a pitch as that if had not been seized on that night the King, with the whole city, had been the day ensuing delivered up without doubt to the mercie of the enemie.

Shi and his plotters were some of several hundred fifth columnists won over by Manchu bribes. They hoped to arrest Zheng Jing during an inspection of Amoy’s defences and hand him over to Yao Qisheng. Now Zheng’s favourite was ‘taken lower by the head & his wifes, as alsoe children, committed to the wide oceans.’[42]

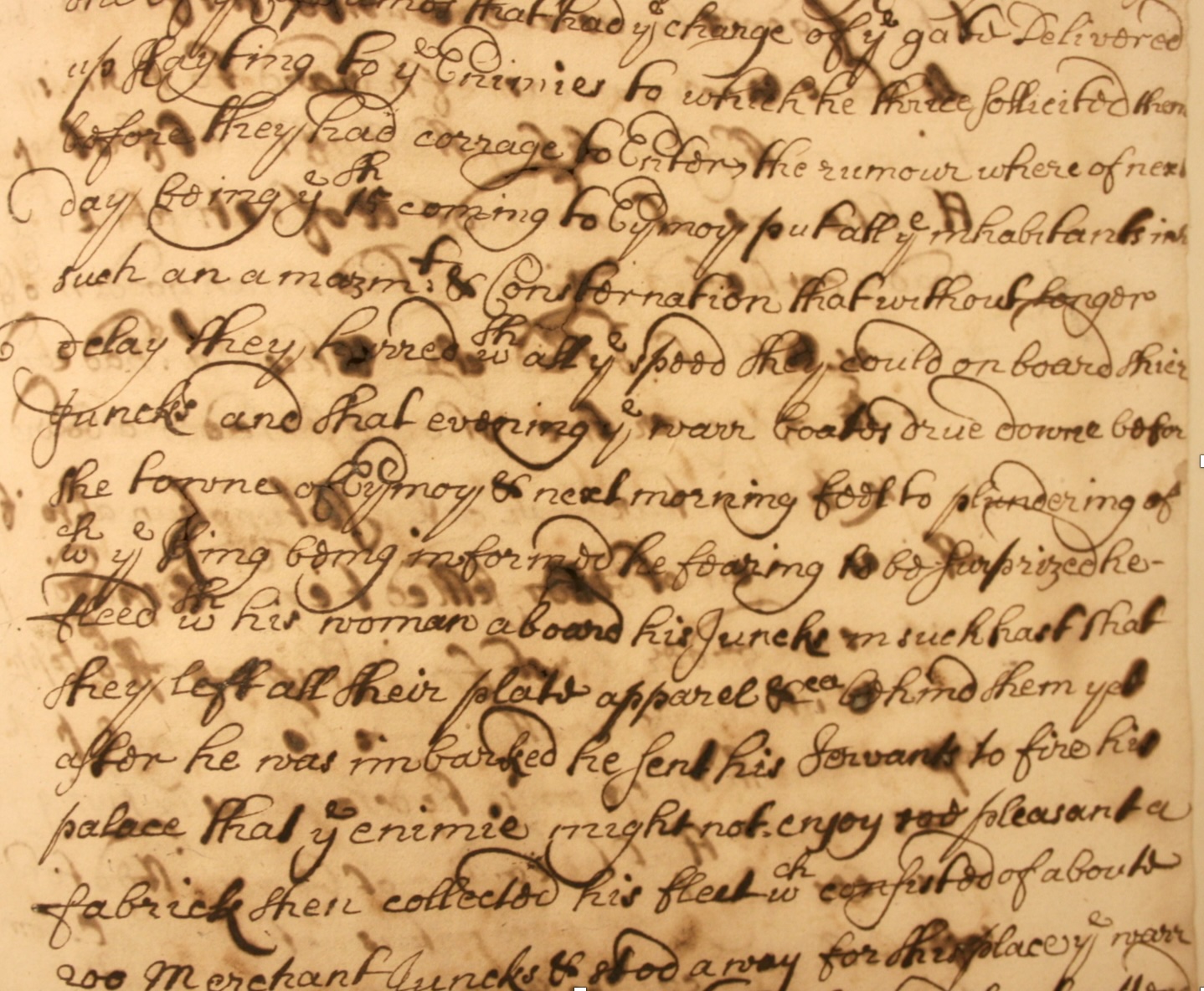

Shortly afterwards, the arrival of the Zheng fleet at Quemoy caused panic in the population. They feared the Manchus were in hot pursuit. They were mistaken but, after he had put their fears to rest, Zheng himself suffered a collapse of confidence. Barwell was at a loss to explain it. Zheng had an ample fleet and army of fifteen thousand or more. They were commanded by a ‘vallient & pollitick generall’ and had been proof against all assault for over a year. Yet, at the first suggestion that the enemy had put to sea, Zheng ordered his troops to quit their lines and withdraw to Pingtan and Amoy. They fell to revolt and pillage. When a rumour arose that Pingtan had been treacherously surrendered, the entire population of Amoy took to their boats:

That evening the warr boates drue downe before the towne of Eymoy & next morning fell to plundering, of which the King being informed, he fearing to be surprized, he fleed with his woman aboard his juncke in such hast that they left all their plate, apparel &ca behind them. Yet after he was imbarked he sent his servants to fire his palace, that the enimie might not enjoy soe pleasant a fabricke. Then collected his fleet, which consisted of about 200 merchant juncks, & stod away for this place (ie. Taiwan).

As the confusion built, Barwell applied to Sincoe for help in getting the factory’s people and goods away. He received none: it had been decided that the population would be put in a better mood for defence if guards were placed on all the quays and nothing were suffered to be carried off. Barwell maintained the pressure and, at last, a junk was provided to assist. He continues,

At the last moment when all the junks in the harbour were under saile a-flying & the soldiers on all sides hovering aboute us ready to seize us, without delay we first conducted them to our monie, expecting all should be delivered into the junck wheron we were to take our passage. But the soldiers were no sowner possessors thereof but forthwith broke open one chest & shared it. Two others the Colonel forced then to put whole into the boate. Afterwards they tooke as much cloth as they could well stow, then called there companions to take the rest of the plunder. Soe carred us to the junke, turned us on board & would not suffer us to take out anything of the least weight or value …

This is the plain truth how in an instant we were miserably dispossessed of all we had upon Eymoy either upon the Honourable Company’s or our owne account, and that which adds to our grief, it was not an open enimie that did us the wrong but the person we took for our best friend and in whome we reposed our greatest trust.

The crossing was not a happy one – the junk had more than a thousand people on board and little food – but, after six days, the refugees landed safely in Taiwan. There, all was in a ‘tottering and unsettled condition,’ as the soldiery were threatening the inhabitants, for want of pay. To keep a revolt in check, the regime extracted extra funds from the population. Barwell decided to close the factory, and then discovered that the severing of trade with the mainland had created a seller’s market. Business exceeded expectations ‘both in prizes & quantities.’ The factors were still in place when, after a perilous voyage, the Formosa drew into the harbour, on 19 August 1680.[43]

Barwell’s pessimism quickly returned. The regime failed to deliver much of the copper that it promised as payment for goods. The value of nearly half of the Formosa’s cargo was added to the debts owed by the Zheng, and she departed just half full. Worse, the increase in the population, with the evacuation from Amoy, caused expenses to rise sharply, so that the ‘rate of provision … [is] not dearer in any part of the world.’ Unavailing attempts were made to obtain a concession on rents. At the end of his letter, Barwell wrote that he despaired ‘of ever doeing good in this trade.’ To save costs, he and George Gosfright returned to Bantam. The factory was put under the charge of John Chappell, who humbly requested relief within the year.

Thomas Woolhouse, writing privately to his sponsor, Sir Joseph Williamson, was even more downbeat than Barwell:

… though at present things appeare to be in some quietnesse, yet in all realitie when those summs of moneyes lately griped out of his poor people indeed shall be exhausted (which cannot supply longer) disturbances will spring afresh, which (God forbid) if should fall out our lives & all other concernes would be plunged into every most imaginable danger.[44]

His gloomy presentiments were not misplaced.

1681-1683: Taiwan after Zheng Jing. London’s Tilt towards Canton

In March 1681, Zheng Jing died from the effects of a surfeit of alcohol and sexual exhaustion, and two generals, Feng Xifan (Hsi-fan), the head of the bodyguard, and Liu Guoxuan, the victor at Haicheng, took over the regime. According to Chappell, they threatened a rebellion if Zheng Jing’s eldest, adopted son, Zheng Kezang (K’o-tsang), were allowed to succeed. Koxinga’s widow who, after the retreat, had criticised her son’s ‘want of talent,’ was forced to consent. She gave the order ‘for the murthering for that hopefull young Prince, who was by the black slaves barbarously strangled.’ His place was taken by Zheng Keshuang (K’o-shuang), Zheng Jing’s eleven-year-old second son, who was betrothed to Feng’s daughter. When the Old Queen died, in August 1681, her second son (Zheng Keshuang’s uncle), assumed the role of pliant regent.[45]

Soon rumours spread that the Manchus were preparing an invasion. They were disseminated to lure Liu (‘Xuntock’) into a trap prepared by disaffected officers working in alliance with some rebellious Taiwanese. The ruse was laid bare, but fears over an attack persisted, and Chappell was in no doubt that, notwithstanding vigorous preparations, the island might easily have been conquered.

In January 1681, London, as yet unaware of what had happened at Amoy, wrote to Bantam expressing their frustration at Sincoe’s ‘monopolising the trade of that place.’ They warned that, unless greater freedoms were introduced, ‘it will turne greatly to His Majestie’s disadvantage.’ For now, they expected trade with the mainland to be weak, but they hoped for a recovery with a return to peace, when ‘the people haveing at present a free correspondence with Japan, it is probable that our English manufactures may … come more and more into esteeme with them.’ In May, they prepared three ships, with £12,000 in goods and bullion, for Bantam to send to Amoy. Significantly, they proposed that one of these should ‘carry off all our remains from Tywan.’

In August, they increased the number of ships to four and suggested, for the first time, that Canton might be the better place for a factory. The reason given was the better quality of its silk, although irritation with the Zheng was probably a factor. Two considerations only gave pause for thought: whether Canton’s viceroy had given sufficient authority to protect the Company’s people and possessions, and whether the Zheng, ‘being at a kind of enmity with the Tartars & people at Canton’ might react by putting the existing business at hazard. The Directors asked for Bantam’s advice but granted its council discretion to send to Canton a small ship with ‘two sober & discreet factors,’ and an investment of £3,000 to £4,000, to make a trial of trade.

As usual, Bantam had anticipated their move. The Formosa was despatched to the Pearl River in July 1681. At the Typa Quebrada anchorage, she sold her entire cargo to merchants visiting from Canton. Consequently, in one of their last acts before their expulsion by the Dutch, in March 1682, Bantam’s Council wrote that they had a Canton voyage ‘in prospect’, although they said they were unsure of securing official liberty to trade.[46]

On 19 August 1681, London heard of Amoy’s fall. Bantam was given latitude to apply to the Manchus for permission to maintain a presence. Nonetheless, London made it clear that ‘that which is most desirable of anything is that wee may be admitted to settle a factory at Canton itself.’ In March 1862, the Directors heard of the pillage of the Amoy factory’s goods. They wrote forcefully to Taiwan’s king, demanding satisfaction and threatening that, if this was not forthcoming, they would ‘right ourselves upon the shipps and goods of any of your Majestie’s subjects that we shall meet with.’ In great irritation, they claimed,

We have long traded with your Majestie and your subjects … without any kind of advantage to ourselves but onely an expectation that in length of time we … might obtaine a greater freedome of commerce and just satisfaction of our debts …But on the contrary, wee understand … that our servants at [Amoy and Tywan] were not suffered the freedome of selling their goods to whome they thought best, and some of their goods were taken from them in your Majestye’s name, for which wee are yet unpaid, our factory at Amoy was betrayed by Sinco your minister, our money and goods there rifled by your soldiers …

Edward Barwell, by then heading the council at Batavia, wisely decided not to forward this ‘menacing’ letter until after the factory had been closed and its officers had been withdrawn. Nonetheless, London had signalled that they were by now much less concerned by the offence in Taiwan that establishing a presence at Canton might cause.[47]

In October 1682, the Carolina sailed from London to Macau. Her officers were told to obtain permission to establish a factory at Canton on the best terms possible. John Vaux was advised to be circumspect, as Canton’s merchants and mandarins were ‘a very cunning deceitfull people,’ but London’s determination is apparent from his instructions:

The more to induce them to grant you a settlement in Canton upon good termes you may propound our sending them 4 or 6 ships of war to serve them in their wars against any but European nations … You may tell them what great and powerfull ships of war the Company have and how many they can send if they were sure of good pay for them … Note that we had rather send them 8 ships of war at one time rather than two, because such a strength would force their way home if the Dutch or others should attempt to obstruct them.

If permission for Canton were refused, the Carolina was to make for Fuzhou and try there. If, after Fuzhou, goods remained unsold, Vaux was told to try Amoy or Taiwan, as the monsoon gave him leave, though he was to give no hint of his intention to the Manchus. On the other hand, if Taiwan had already fallen, he could offer the Manchus assistance with their shipping, whilst pointing out that the Dutch could not do the same, because of their trade with Japan.[48]

When she reached Macau, in June 1683, the Carolina met with a cool reception. The Portuguese explained that they were being pressured by the ‘Tartars’ extortion & strict hand,’ and by the effects of the war. They said they had been placed under an injunction not to trade with other Europeans when, in fact, they had purchased a monopoly at considerable cost. Moreover, they told the Manchus that the Carolina was a Dutch ship, and that the English and Dutch had been supplying Taiwan with ammunition and weapons. For several months, the Carolina was bustled between Macao and Lantau Island, as Vaux endeavoured to engineer an opening. Then, on 17 September, there was an encounter with some Dutch vessels from Fuzhou. Vaux wrote,

In coming from thence they mett with several hundreds of Tartars & Laderoon boats going for Tywan & told them that they had already taken the Piscadores & that the King of Tywan had surrendered up himself under the protection of the Emperour of Pekin. So that if it should prove true, as it is much feared, your Honours’ factory is ruined & all lost, the Tartars having lain against it this many moenths with a great force & supposed starved most of the inhabitants, which forced the remainder to surrender.

A little later, some Portuguese travelling from Amoy confirmed that Taiwan had indeed fallen: three Englishmen and four or five Dutch had been sent as slaves to Peking. Vaux feared that ‘there will be no ransom for them from the hands of such sodemitish cruel people,’ but his fears were misplaced. The three Englishmen at the factory remained in harness. John Chappell had taken passage to Batavia, but he left behind Thomas Woolhouse and Thomas Angeir to manage affairs. They were supported by the apprentice, Solomon Lloyd.[49]

A little more than three years had passed since Zheng Jing had evacuated Amoy. The intervening period had been taken up with diplomacy. At the end of 1680, the Manchus had again offered Taiwan to Zheng as a hereditary possession, on the grounds that it lay ‘outside the domain of the Middle Kingdom,’ provided he abstain from harassing the Chinese coast. When Zheng insisted again on the joint management of Haicheng, the Fujian governor, Yao Qisheng, determined on invasion. But action had been delayed by a disagreement over tactics between Yao and Shi Lang (Shih Lang), commander of the provincial navy. This gave Feng and Liu the opportunity to build a naval reserve. They sent two hundred ships and twenty thousand men to Penghu, which Zheng Jing, unaccountably, had left unprotected.

A last effort was made at peace. Immediately before departing Amoy, in January 1683, John Chappell wrote of the arrival of envoys sent by Yao to discuss a treaty. He expressed the hope that, if they succeeded, ‘then our Europe goods will be most in esteeme.’ The Kent, in which he sailed, carried with her 1,100 chests of copper and over four tons of camphor. They were valued at over 43,000 rials, which was encouraging, even if garnering the cargo had been troublesome. Yet, Yao’s initiative was built on sand. It represented a last effort in his battle for influence with Shi Lang. His timing was opportune in that a Manchu campaign in Guangdong had severed Taiwan’s most significant grain supplies: with famine pressing, Feng responded positively to his overtures. But Shi refused to receive Feng’s envoys, and, in June, he secured the emperor’s veto over the initiative. Tributary status was ruled to be inadmissible. ‘Taiwan are all Fujianese,’ declared the emperor. ‘They cannot be compared to Ryuku or Korea.’[50]

In May 1683, there was a skirmish involving a Manchu scouting fleet at Penghu. Once it became clear that this was not Shi’s main armada, Taiwan’s underpaid and underfed defenders were allowed to return to their farms. Then, on 30 June, a fleet of four hundred junks came into view. Angeir and Woolhouse reported that,

On the day ensuing … was a stiff engagement but the Chineis (the Zheng) got the day with the losse of about 1000 persons after had sunk and burnt some of the Tartarian junckes, makeing them retreat through the apparent valour and conduct of Lim Eubooweigh (Lin Sheng) the Vice-Admirall, who played the part of a mighty man of valour and received not a few wounds into the bargaine.

According to the Taiwanese records, a frontal charge by Lin Sheng drove Shi’s fleet southwards to some of Penghu’s remoter islands. Liu Guoxuan was advised to pursue it at once, but he feared that his famished crews would mutiny if he overtaxed them. Instead, he put his faith in the storms of the season. This was a mistake. The next day brought news that two hundred additional junks had joined the enemy. On 7 July, there was another stiff engagement. ‘Through the irresistible multitude of them being over-prest,’ the Zheng surrendered. Shi Lang accepted their submission, ‘putting never a soul to the sword after landing his army in the Pescadores.’ Liu Guoxuan narrowly escaped.

It had been a ferocious, one-sided battle. Shi Lang lost several ships, two of his commanders and 329 crew; the Zheng 169 junks and twelve thousand crew. More than four thousand others surrendered to the Manchus, and forty-seven commanders perished. At this news, report the English factors,

… the whole countrey was struck with so great amazement that they were as people intoxecated and instead of a preparation for further resistance fell to rites, to shutting their shops, desisting all necessarie commerce, flying with wifes and children into the mountaines, burning their money and setting all the powers of their imaginations a-work to devise, if possible, some means to preserve their lives, proposeing to themselves that Sego (Shi Lang) would out of hand prosecute his utter enemies who had formerly put all his race that ever came within their clawes to the sword.[51]

1683-1685: The Taiwan Factory under the Manchus

These worst fears were ill-founded. Shi was alert to his opponents’ disintegrating morale, treated his captives with leniency, and permitted those who were so minded to return home. They spread the news that any who wished to join the Manchus would receive pay equal to the victors. As famine intensified and some commanders threatened to defect, ambassadors were sent to Shi, who,

… protested and swore before his wooden god that if the countrey were surrendred to him without shedding of more blood he’d not kill a soul of them.

On Taiwan, Feng Xifan argued that the regime should decamp to Manila, and re-establish itself under Koxinga’s third son, Zheng Ming. He was opposed by Liu Guoxuan, who fanned fears that his expedition would plunder Taiwan before abandoning it. In a bitter exchange, he advocated surrender and, since he controlled the largest share of the forces, he won the argument. Zheng Keshuang, who had no say in the matter, was sent to negotiate. His request that he be permitted to remain in Taiwan as hereditary ruler was summarily rejected. On 30 August, the population was ordered,

… in the name of the Great Cham of Tartary, to shave all their hairs off save enough to make a monkey’s taile pendent from the very noddle of their heads.

According to Angeir and Woolhouse, a ‘first great part of the commonaltie’ did as they were instructed, though with ‘no very hearty compliance.’[52]

Zheng and his officials were told that they might consider whether to do the same but, in truth, they had no option. By 23 September, Shi had brought two hundred junks and ten thousand men into Tainan. A few days later, the senior Zheng were ‘tartarized’. Zheng Keshuang,

… had the honour to be made a King againe by the receipt of a large chop from His Imperiall Majestie … and on the 19th of November set sayle out of Tywan bar toward the maineland for receipt of a kingdom.

With him sailed his wives, his brothers, all the senior mandarins, and all of the Company’s hopes for recovering debts estimated at over 6,700 taels. After some forty years, the Zheng regime had come to an end.[53]

Angeir and Woolhouse were more than a little perturbed. However, before the Manchu expedition sailed, Yao Qisheng had put the factory under his protection. A Manchu banner flew from its flagpole and orders had been affixed to its doors prohibiting anyone from interfering with it, on pain of death. Building upon this start, to open a path to trade on the mainland, the factors offered the three senior Manchu commanders some cloth, as a bribe. There was one problem. Stocks were scant and they feared its value (£102) would appear niggardly. They were not mistaken.[54]

On 10 October, they received news of Shi’s charge that the English,

… have for these eleven or twelve years brought ammunition, as powder, musquets, cut flints and what not, and moreover upon the mainland of China have not omitted (being friends of this next of theives) to send people expert at armes to fight against us … declareing themselves absolute inveterate enemies to my Imperiall Lord and Master Counghee, Emperor of the Tartars.

Shi refused to believe that the factory’s stocks were as small as had been claimed. A hundred muskets (however broke and rotten) and two casks of flints, which had gone unreported, were discovered in its cellar. The factors were ordered to render a full account of its assets, ‘silver & gold and debts besides.’

Perturbation turned to panic. Angeir and Woolhouse became ‘as people half-witted.’ They were advised to pacify Shi with a bribe of between two and three thousand taels in gold and silver. His accusations were exceptional, they were warned: at a minimum, they would forfeit everything and suffer perpetual imprisonment. They might be executed. Shi’s nephew, who was deputed to deal with the dispute, professed himself convinced that the Company’s stocks were worth ten times as much as had been declared. He offered to intercede and have a portion of the bribe converted to goods – at the price of two hundred taels, ‘which none of the other servants must know of.’ Angeir and Woolhouse capitulated. ‘To lose a hog,’ they reasoned, ‘would be the vastest imprudence for a halfpenny worth of tarr.’ The sweetener was paid, and a complete account rendered, with gifts in gold, copper and cloth worth 3,090 taels, and a request that Shi petition the emperor for a right to trade with the mainland.[55]

The bribes spared the Englishmen imprisonment, but the style of Shi’s proposal was not what they anticipated. They were to submit an appeal in writing, explaining that, five years before, two of their ships had landed in Amoy, ‘though the unhappiness of a bad wind.’ A year later, when the Manchu expedition had expelled the Zheng, they had been forced to take refuge in Taiwan, where they found themselves friendless in an alien land. Shi had given proof of the emperor’s mercy and benevolence, and this had inspired them,

… to pray for and praise your Majestie for such mighty and apparent goodness, with our request that out of the fountaine of your royallest favours would be out of your princely wisdome graciously pleased to admit us to returne to our native countrey by the first opportunity, for which your favour we shall never cease praying the Almightie Creator, King of all visables and God of all existence, to bless your Imperiall Majestie with a long and happie life here, the success of affairs and enjoyment of eternitie.

The Englishmen were greatly puzzled. What was to be gained by these ‘ridiculous stories’ and ‘abominable and apparant lyes?’ No appeal for an opening in trade was apparently being contemplated. They resolved to make a fire sale of everything and catch the next junk to Siam.[56]

On 7 December 1683, there came a change of heart. Seemingly because he needed the income, Shi declared that he supported trade with Europeans in Taiwan and at Amoy, and he encouraged the Company to send ships to both places the following year. Angeir and Woolhouse decided that to cut and run would be a mistake: the Manchus would ‘stumble at a straw provided in contradiction to their interest, and jump over a mountaine where can ketch the least advantage.’ Solomon Lloyd was sent alone to Siam to make a report.[57]

Meanwhile, in London, the Directors – still unaware of Taiwan’s fall – were having some second thoughts. They were greatly vexed at the ‘want of care and honesty’ of their former council at Bantam, whose failings (they judged) had quite eaten up the profits of the northern factories. Writing to Fort St. George, on 2 July 1684, they confessed that, at one point, they had quite wearied of them. Yet they were loath to ‘to give up Such profitable trades to the nation intirely to the Dutch.’ Instead, they transferred responsibility for them to Madras, hoping that, under their vigilant care, the factories would take root and prosper.

The Directors had just received John Chappell’s letter of 31 January 1683, in which he had referred to Yao Qisheng’s final efforts at mediating a peace, and his hopes for trade if they fructified. It made them quite optimistic. They wrote,

If ever there should be a peace between Coxhams posterity and the Emperour of China, that place (Taiwan) may prove a great mart of trade and if the Chineeses can possibly be induced to reside Some of them at ffort St. George, We hope their numbers would Soon increase there to the great inriching of that place.[58]

By now, the focus of their attention had definitively switched from Japan to China. In a letter to Taiwan, they explained their intention: the factors were to tell the Zheng that, if the English were better treated, and a peace was secured with the Manchus, the Company ‘could as well send them ten ships as one.’ Madras was a great city, with thousands of inhabitants; the king should send some of his subjects so that they might meet its president and give a true account of it.[59]

Then, at the end of September, the Directors learned of Taiwan’s fall. Upon reflection, they thought that, if the Manchus permitted the Company a trade,

… it may probably be better then it was under the Chinese (ie. Zheng) Government, because that Island having a communication with the Mayn may afford more comodities and of more various kinds now then it did formerly and take off a greater quantity of English manufactures.

Yet, permission was far from certain. So, they recommended that a small vessel, with a small cargo, should be sent to test the waters and, if necessary, ‘bring off our people.’

In a letter to the new ‘illustrious and famous Vice-King of Taiwan,’ they welcomed the victory of his emperor, and requested that they might continue to trade as friends:

It cannot bee unknown to you [they wrote] that wee have long had a peaceable trade at Tywan and our factors have resided there in the management of our trade for above 12 years without intermission, to the enriching inhabitants of that place, which althugh they were at enmity with the Tartars neither our ships nor our servants did ever interpose in that quarrell but only follow their trade quietly as merchants strangers, which have a right of being protected by all nations where they meddle not with anything but their own affairs.

This was a bold claim. (Shi Lang, for one, would not have been persuaded.) In the same letter Madras was warned that the Manchus were a ‘sligh, crafty and treacherous people,’ and that they should avoid danger until they were sure they would be treated as friends. In truth, the Directors were no less duplicitous than they considered the Manchus to be.[60]

Once again, however, London was behind events. In February 1684, Solomon Lloyd reached Siam, where he reported on Taiwan’s capture, the Manchus’ grant of a free trade at Amoy, and the need for the Company send a merchantman.

1684-1685: The Voyage of the Delight. Factory Closure

In the harbour, he encountered the Delight. She had arrived the previous October, after missing her passage for Macao, where she was to have joined the Carolina. Lloyd’s timing was opportune as, the day before, the Delight’s supercargo, Peter Crouch, had been arrested by the Greek, Constant Phaulkon, for refusing him a gift of some nails.

Earlier, in November, Phaulkon had informed Crouch,

… that it was God’s great mercy that wee had lost our passage, for had wee proceeded to our desired port wee should most certainly have been cut off by the Tartars, representing the voyage as the most dangerous & inadvertent thing in the world, they haveing not only prohibited all strangers, Europeans, comeing on the coasts but had alsoe more especially declared the English to be theyr enemyes upon account of assisting the Chineses against them.

Crouch had been unsure of how to proceed. Now Lloyd’s evidence convinced him that the Delight should sail. The nails were handed over, Crouch was released, and in early April, the Delight departed for Macao.[61]

Things started badly when, upon her arrival, John Thomas, formerly a merchant on the Carolina, began to display the symptoms of an earlier derangement. His fits of passion grew more violent until he was removed to a secure cabin. When, a little later, he was allowed on deck,

… he flung himselfe overboard, imagineing that he saw 2 shipps which he had minde to speake with. But he swiming & it proveing something calme, he was with the boate (being hoysted out) brought againe aboard & confined to his cabbin, severall dayes continueing in the same condition. But with the wane of the moone seemed to mend, which incouraged us to beleive that he would in small time doe well. But wee were disappointed, for the moone increasing, his distemper alsoe increased to that higth that least he should affront the Chineses at that time dayly comeing aboard or doe himselfe any harme by his venturous climbeing &ca, wee were forced to chaine him with a small chaine about his middle, fastened to his cabbin.[62]

Other problems had to be faced. One was the demand for ‘piscash’. An offer, equivalent to £10, proved inadequate. Crouch hoped for a meeting with Macao’s governor but, after a two hour wait, in the sun, he was told he was indisposed. His lieutenant’s incivility persuaded Crouch to abandon the attempt. Already, his stay at Macao Roads had suggested the prospects for trade were as the Carolina had found them. On 22 May, the Delight repaired for Amoy.

Immediately, officials made a detailed examination of the ship and its cargo ‘for prevention of any trouble that may otherwayes ensue.’ There were demands for gifts for the regional commander (‘Euchongia’), the assistant commander (‘Chu Toyea’), and for ‘Lochungia’, the deputy representative of the emperor. Others followed for Yao Qisheng’s successor, and Lochungia’s superior, ‘Chunkung Twalawyea’. Chu Toyea drew Crouch to one side. He advised him to explain that the Delight’s failure to make her rendezvous with the Carolina necessarily put a limit on English generosity. The suggestion availed Crouch little. On 5 June, a letter arrived from Fuzhou. It indicated that the governor was supportive of open trade, but charged,

… wee had done very ill in bringing 4 things serveing for warr, vizt. brass guns, musquetts, gunpowder & lead, & desired to know upon what account wee brought them, whither to present the Emperour.

Crouch applied his wits to the question and answered that the armaments were but examples of the products of his country. They had been loaded because they might once have been of interest to His Majesty. Now that the war was over, it were best to return them to England. The mandarins were unimpressed. It was scarcely credible, they said, that when they had a factory on Taiwan, the English would have countenanced supplying arms to the enemy ranged against it. The implication was clear. Crouch was told that, unless he handed the items over, he risked the loss of his ship or, at best, being sent away ‘without trade or for the future.’ Crouch knew he was beaten. He persuaded the mandarins that the Delight needed armaments for her return journey, but six cannon, thirty muskets and fifty barrels of powder were presented to the emperor ‘in token of amity &ca.’

Still, it took a long while for the trading licence to materialise. Only on 28 September was it announced that the emperor had given the English his blessing, and a waiver on customs fees. In between times, there were demands for further gifts. These had to be dispensed if the Delight’s merchandise was to be unloaded (necessary because she was leaking), or her gunpowder was to be removed to safety (a Chinese requirement), or if the old factory was to be used for accommodation. The outlay was a substantial 1,100 taels.

As soon as it was paid, the English were ordered back onto their ship. Their factory was being requisitioned for the Dutchmen of the Chilida, which arrived to collect some former prisoners of the Zheng. Crouch was greatly displeased. The factory had been repurchased at a dear rate, and now the English were being told to make way for the Dutch, ‘a thing not known by us throughout the world.’ The matter took over a month, and more expenditure, to resolve. It was embarrassing therefore that, at the factory’s formal re-opening, John Thomas, under the influence of his ‘lunatic malignity’, wandered off with the keys. Amoy’s official for foreign trade looked on as the doors were opened by the expedient of having their hinges removed.

Manchu bureaucracy ground slowly (the Dutch faced similar obstructions), but to charge that this was due solely to venal officials would be unfair. The conduct of several Englishmen fell short of what might have been expected. John Thomas was a handful but so, after he arrived from Taiwan, was Thomas Woolhouse. He and Crouch quarrelled over who had greater authority, and, at best, they worked in strained equilibrium. Although he did not yet know it, Thomas Angeir had already been dismissed from the Company’s service for his ‘dissolute carriage’ and ‘excessive intemperance in drinking.’ It seems that the Directors were justified in criticising his resort to the bottle. One letter, from July 1684, reads,

Mr Thomas Woolhouse,

On the 9nth instant by Changkoe’s conveyance I received two quart bottles of brandy &ca. Pray pardon all nonsense, for I am so ill disposed that I don’t know what I doe write. I have sold lead to the value of fifty od tales. Pay for fraight six mass of fine silver.

Your friend & servant.

Thomas Angeir

It is faintly comic that, in his next, he commiserated with his colleague,

… that our Masters should send out such a debauched fellow as Navarro (a Portuguese interpreter), for by relation of Solomon Lloyd he is a wicked vile person and is not fitting to live among sober persons. I am very well satisfied with your resolution for his returne (to Amoy) and will set both my hands to, for am not accustomed to live among such persons, nor is it convenient that he should remaine in the Companie’s service.[63]

Angeir was declining fast. He was lame in both feet and losing the use of one hand. On one occasion, he shut himself away for two or three days with some soldiers, gambled away twenty taels and claimed, at the end of it, that it was money well spent. Solomon Lloyd feared his behaviour was earning for the English a gamester’s reputation, and that Angeir ‘will give but a sorry account when come.’ So it proved. When he departed for Amoy, in October, he failed to square with his successor the state of the factory’s stock, something that might have been achieved in minutes, if Lloyd’s letter gives a fair description of the residue that remained. The Company’s books were squirrelled away in Angeir’s travelling chest. He took with him the chop that permitted the staff to slaughter one buffalo a week, for food.[64]

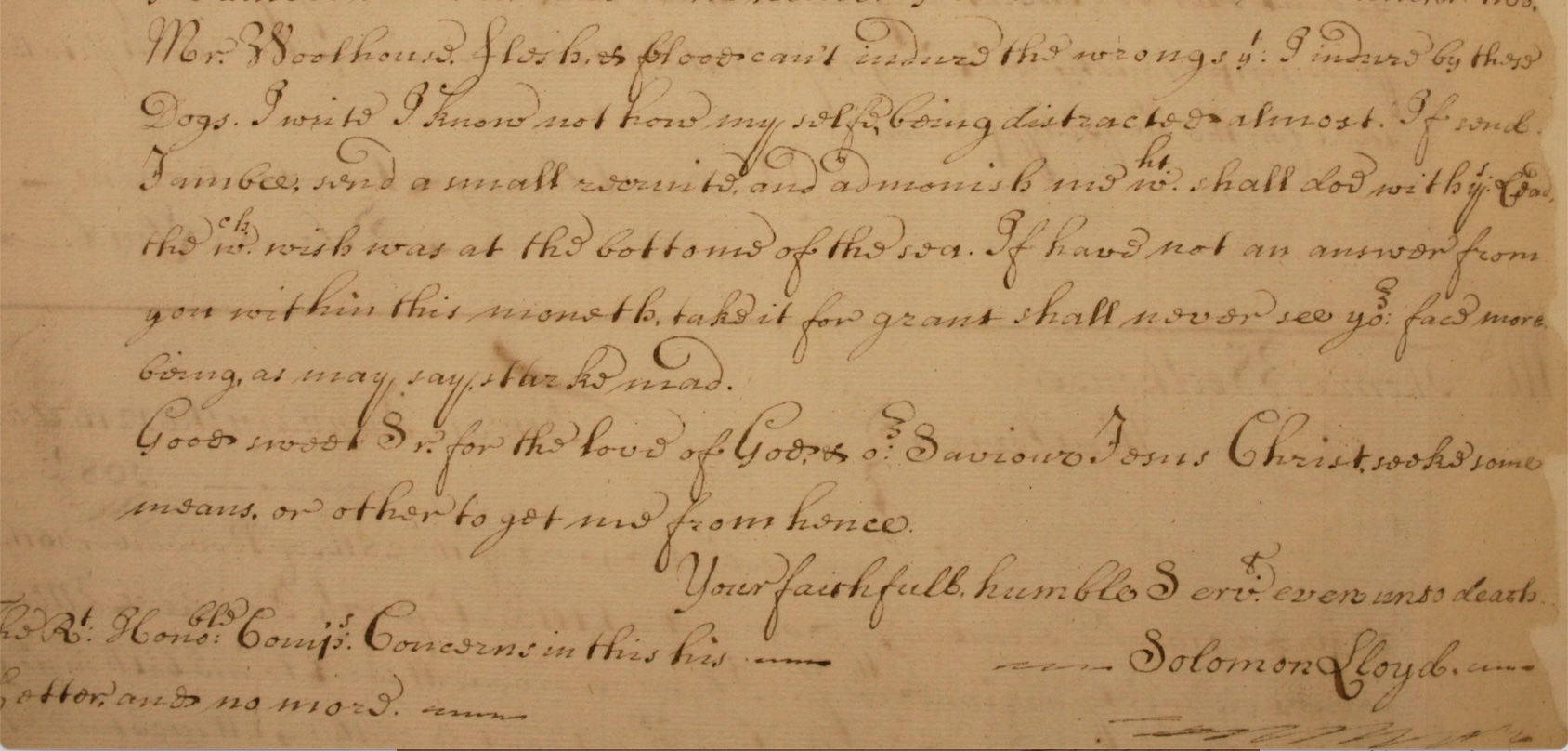

Yet Lloyd quickly missed his company. Almost immediately, his fraught language became desperate. In a letter to Woolhouse, dated 19 October, he wrote,