Taking comfort from this slightly better gloss on events, the English prepared another voyage. William Adams was its main sponsor; he was accompanied by Edmund Sayers. As they made ready, Cocks wrote optimistically to London:

Yf we may get a quiet trade into Cochin China there we may be sure to have raw silk every yeare in greate quantety. Som yeares there cometh above 1000 picos from that place only into Japon …& is bought at a resonable rate that many times they make three for one profit, but all or most part is done with ready money. Yet, having once a fyt stock for that place & quiet trade (as Capt’ Adames maketh no dowbt but to obtayne), then may we assuredly make retorne yearly of greate soms of money to Bantam … for it is certen there cometh twise as much silk yearly to Cochin China as ther doth to all the 3 placese of Bantam, Pattania and Syam, & wantes not other good peecese of stuffs.

Before the expedition returned, in August, Cocks received some additional positive news: the king of Cochin China was encouraging the English to come in their own shipping and not in Japanese,

… for that he hath banished them out of his cuntrey, I meane the renegages enhabeting in those partes, which did all the mischeefe before.[5]

Even so, the voyage was unsuccessful. William Eaton wrote that ‘there was noe silke to be had but verey littell, & that above 170 tayes (taels) the pecull.’ Nor was there any prospect of recovering Peacock’s goods. In February 1618, Cocks wrote to explain that the mestizo had been quite incorrect in his earlier report. Adams and Sayers learned that Peacock had been,

… murthered by a Japon, his host, w’th the consent of one or two of the cheefest men about the Kyng, and, as it is said, the yong Prince was of their councell. But the ould Kyng knoweth nothing thereof but that he was cast away by mere chance or misfortune. These greate men & his host shared all the goodes & money amongst them, as well of the Hollanders as th’English, whome were slaine all together in one small boate, it being steamed (rammed) or overset w’th a greater full of armed men.

Cocks added that the governor had treated Peacock well, offering privileges to trade in his dominions, and that the Englishman’s demise had been caused by his unseemly conduct:

… one day a greate man envited hym to dyner, & sent his cheefe page to conduct hym, he being sonne to a greate man, but [when he came to the?] place wheare Mr. Peacock sate, [he gave hym hard] wordes and bad hym goe out & sit w’th the boyes. And, as som say, being in drink, he tore the previlegese the King had geven hym for free trade & cast the peeces under his feete. These & other matters (w’ch is reported) he did did much estrang the peoples hartes from hym, & … was the cheefe occation w’ch caused his death.

Initially, the governor had been willing to meet with Adams and Sayers. Then, when they raised the matter of Peacock’s death, the governor’s son, ‘being giltie of it’,

… put them affe from tyme to tyme w’th delaies, & in the end did flatly gainsay them, & had they gone out of dowbt they had byn murthered in the way.[6]

The governor’s son assured the Englishmen that he would obtain for them ‘what sooevere [they] would Requeste ffor a trad in to the Contre,’ yet, denied their interview with his father, they received no payment for what Peacock had sold.

Their own voyage was modestly successful, until Sayers was robbed of a third of the Company’s investment by his interpreter. Encouraged, whilst he awaited the arrival of a supposed silk merchant, to place his bag of cash against the rattan wall of the interpreter’s house, he was appalled to discover that the wall was not proof against thieving fingers from within. It took him an hour to realise that the bag, and his interpreter, had disappeared.

William Eaton met with no greater success in obtaining payment for Peacock’s sales. In June 1616, after he had offered to involve the Japanese shogun, he had been incentivised to obtain collection of what was due. But the shogun refused to become engaged and, in April 1621 – nearly seven years after the first reports of Peacock’s death – Eaton was still trying, and failing.[7]

After this, there is no record of English involvement in Vietnam before 1672.

Connecting Indochina and Japan

European interest in Japan had first been stimulated by its role as a supplier of silver specie for, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, an increase in Japanese production meant its value relative to gold fell to about half the level that applied in China. (Chinese demand for silver was almost insatiable.) The difference arose at a time when the Ming refused Japan’s ‘dwarf robbers’ entry to buy the silks they desired, and it was upon this opportunity that the Portuguese established themselves as intermediaries in Macao (c.1557). Before long, their exports of silks – the medium of exchange preferred by the Chinese – were consuming more than half of Japan’s silver output. Where the Portuguese led, the Dutch followed, sourcing product from ports in south-east Asia, such as Patani. By 1611, William Adams, who reached Japan on the Dutch ship Liefde, in 1600, was telling the Company’s representatives in Bantam that ‘the Hollanders have here an Indies of money.’ In 1612, he advised that,

… can our Inglish marchants get the handelling or trad with the Chinas, then shall our countri mak great profitt, and your worshippful Indiss Coumpany of London shall not hav need to send monny out of Ingland, for in Japan is gold and silver in aboundance …[8]

It was in search of an alternative supply of silk that Richard Cocks sent Peacock and Carwarden to Cochin China, in 1614. Yet, the references in Cocks’s diary to the different regimes of ‘Cochinchina’, ‘Tonkin’ and ‘Champa’, are clues to the political crises by which Vietnam was then riven. These began long before, in 1527, when the Le dynasty, which had controlled much of Vietnam since the 1420s, was overthrown by Mac Dang-Dung. For, although the old regime had been toppled, it found a champion in the guise of the Nguyen.

When, in 1545, the head of the Nguyen was murdered, they controlled much of the southern half of the northern part of the country. At his death, Nguyen Kim’s sons were minors, so he was succeeded by his son-in-law, Trinh Kiem. When the minors grew up, Trinh Kiem was challenged. One of the challengers he killed. The other, Nguyen Hoang, he sent to govern the provinces in the south that had been conquered from the Cham. Thus, in 1570, when Trinh Kiem died, the Le Kingdom was essentially divided into three territories. To the north, in Tonkin (around modern Hanoi), were the Mac, now officially recognised by China. In the upper middle part (around Thanh Hoa and Vinh), the rulers were the Trinh. Further south, in the former Cham areas around Hué, ruled the Nguyen.

In 1592, the Trinh drove the Mac out of Hanoi and three territories became two. In 1600, the Nguyen and Trinh broke relations and, in 1620, a war commenced between them. It continued until 1674, when the two sides agreed on a common border demarcated by a system of walls. They consolidated their power to the north and south. In the north, the Trinh drove the Mac out of their residual lands while, in the south, the Nguyen expanded into the territories around Saigon and the Mekong still controlled by the Cham, and into Cambodia.

After the English retreated from South-east Asia in 1622-1623, the Dutch retained their factory in Japan, and persisted in their efforts to exploit the trade of the China Sea. In 1634, Jeremias van Vliet returned as agent to Ayudhya. A factory followed in Cambodia in 1637 and, in 1641, Gerrit van Wuysthoff journeyed up the Mekong to Vientiane. In 1636 or 1637, Abraham Duijker instituted a factory in Nguyen territory at Fai-Fo (Hoi-An) and, in 1637, Karel Hartsingh was sent from Hirado to establish relations with Tonkin. He inaugurated a factory in 1649, which remained in being until 1700. Including the base established on Taiwan, in 1624, these were the hubs of a trading system focused unashamedly on Japan, from which the Portuguese – because of their evangelising tendencies – were now excluded.[9]

After their earlier withdrawal, the English did not return to the mainland of South-east Asia until 1651. In that year, Quarles Browne set up a factory at Longvek, near modern Phnom Penh. However, although he had been sent by Aaron Baker, the president at Bantam, to source benzoin (for incense), in constructing an establishment he exceeded his instructions. When London discovered (in February 1654) what he had done, they expressed – with a blast of irony – their ‘great admiration … that there is a Factory set up in Camboja without our privitie or allowance.’ Fort St. George was informed, in blunt terms, that its capital would have been better employed in Bengal or on the Coromandel coast. In June, Baker’s replacement, Frederick Skinner, was reminded of the criticism meted out to his predecessor and instructed to ‘ease us of that Charge.’

Although it is possible to sympathise with Browne’s motives for building the factory – he judged renting accommodation would be no cheaper – by October 1654, the establishment had swollen to comprise two houses, a cookhouse, a steward’s room, accommodation for slaves, and a godown. The whole was surrounded by a 150-fathom stockade. The cost was much higher, and the market for benzoin less lucrative, than Browne had anticipated. He was fetched away, probably at the end of 1656, and packed off to London, to face charges of mismanagement (of which he was later acquitted). It is true that Henry Hogg remained. It is also true that, in the summer of 1657, Hogg was joined by John Rawlins, who was issued with a commission in the Company’s name, by Skinner. However, theirs was a private venture. Skinner neglected to inform the Company of Rawlins’ appointment, and, in due course, he too was summoned to London, to answer charges of embezzlement. And so, just as it would be wrong to ascribe the temporary operation of a factory at Ayudhya between 1661 and 1664 to the deliberate strategy of the Company, the same should be said of English ventures in Cambodia between 1651 and 1659.[10]

Following his vindication by the Directors, Quarles Browne returned to the ascendant. In September 1658, he was selected to be chief factor in Japan. His voyage was later abandoned, and, for a period, he ceased to be employed by the Company, but Browne maintained relations with Sir Thomas Chamberlain, its Deputy Governor. In 1661, he presented to him an account of the trade of Cambodia, Siam and Japan, in which he stressed their interdependence. (Browne termed the Chinese ‘a deceitful people’, but the Japanese he considered ‘the noblest merchants in those parts,’ and it was with Japan that he was chiefly interested.) In May 1663, he returned to Bantam, as agent. At the end of the following year, he responded to a suggestion that a ship from England might quickly call at Cambodia to take in commodities before sailing to Japan by saying it was much too casual an approach. Dutch competition made it necessary to establish a factory in Cambodia or Siam a full year beforehand. A factory in Tonkin, for the securing of raw and finished silks, was another prerequisite.

As it happened, the outbreak of the second Anglo-Dutch War meant that the Company’s ship did not sail and, in July 1665, Quarles Browne died. Even so, he had set the germ of a change in London’s policy. In 1668, a committee considering ways of developing trade with Japan and Manila received submissions promoting the cause of bases in Siam and Taiwan. In April 1669, the Directors sanctioned the opening of a factory in Cambodia and, in October 1670, factories in Taiwan and Japan. When, in April 1671, Cambodia was judged too much a ‘turbulent disordred place,’ it ceded its position to Tonkin.[11]

The Experiences of William Gyfford (1672-6)

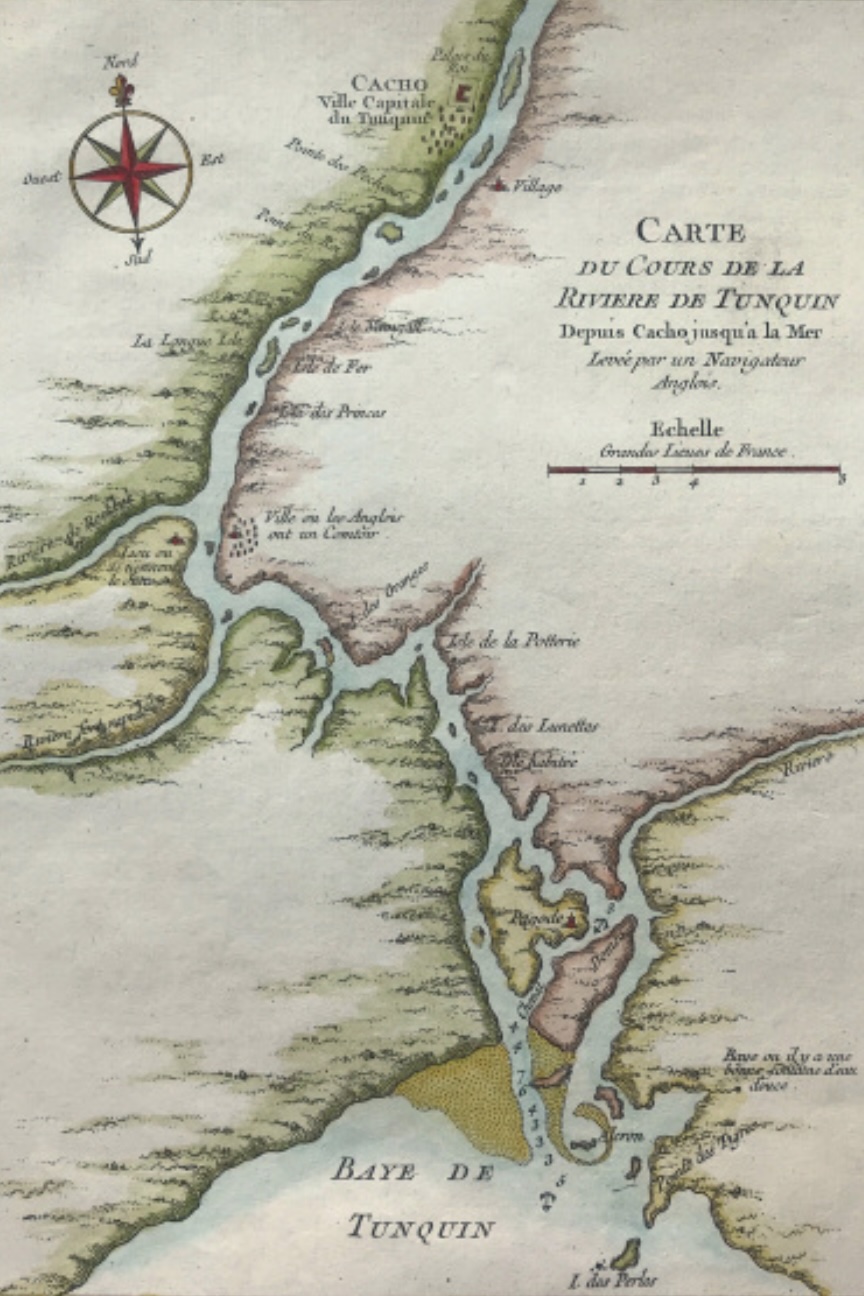

In September, the Return, Experiment and Zant were readied for sail. William Gyfford, taking the Zant, was to establish a factory at Tonkin to supply musk, silk, hides and tutenague (zinc-copper alloy) for the Japanese market. When these had been exchanged for Japanese silver, Tonkin was to be used to source such commodities as might be sold in Europe and India. Sales of more European and Indian goods were to be used to supply silks for Japan in the following season.

The expedition was a failure. A factory was established in Taiwan, which remained in operation until 1685, but the Dutch informed Japan’s Tokugawas that the English king was married to a Portuguese. As a result, they refused permission to Symon Delboe to start operations at Nagasaki. After an unproductive stay of two months, he quit Japan for Macao and Siam, in August 1673.

These developments lay in the future when the Zant crossed the bar of the Tonkin River, on 25 June 1672. She reached Hung Yen (‘Hean’), about half-way to Hanoi (‘Cachao’), three days later. The Trinh officials were anything but cooperative. By interfering with the handling of the ship, they imperilled her safety. Gyfford writes,

In sayling up the river the ship severall tymes touched & the mandarine being this day aboard [pinioned?] the Captain & threatned to Cutt of the Cheife mates head because they would not Tow the Ship against a violent streme. Which at last they were forced to try but as soone as the Anchor was up the Tyde or Currant carried downe the ship in spite of all helpe, soe hee was something appeased.

The mandarins insisted on full particulars of the Zant’s cargo, to the factors a strange custom, but one with which they felt bound to comply. They also demanded a complete list of presents for the Court. This the factors were unwilling to surrender without ‘some assurance of a Trade,’ until they felt bound to ‘give them content.’ Dispiritedly, they declared,

This action of the Mandarines wee cannot yet tell what the meaning of it may bee or how it can consist with a good correspondence hereafter. wee judge patience to be our best remedy yet were it not that wee have respect for the Companys affaires and if wee would not bee thought to ympede their designes by any rashness of ours, wee should have resisted and not have suffered any such affront, though wee saw but litle hopes of escaping being soe farr up the River and our Ship soe full of souldiers.

After just one week, Gyfford declared there was no point remaining. His protest produced no useful effect. Instead, the Zant was impounded. According to the journal,

Gyfford said wee were very willing being strangers to be observers to their Costomes and Lawes, only such unreasonable imposicions as these of forceing a Ship to goe against wind and Tyde and putting such [….] upon us as to [pinion?] the Captain seemed very strange to us and therefore wee desired noe other [favours?] from him then that he would give us leave to goe back againe for that wee beleeved our Honorable Employers would not trade here upon such termes as these.

To this the Manadarine Answered that while wee were out, wee might have kept out. The King was King of Tonqueene before wee came and would be after we were gone and that this Countrey hath noe neede of any forreigne thing but now wee are within his power wee must bee obedient thereto compareing of it to the condicion of a married wooman that can blame noe body but her selfe for being brought into bondage.

At this, the English concluded – not unreasonably – that the Tonkinese had ‘very little affecion … for trade.’ Yet, the river’s bar was impassable unless the direction of the wind changed. Gyfford resigned himself to a long and wearisome stay. He complained of the charge of satisfying the chief mandarin’s taste for wine, not least because he passed it around his officers, and ‘forced them and our Seamen to drinke up full Cupps onely to devour it.’ He continues:

This evening the Ship ran ashoare againe at the Top of high water and the Captain could no wayes bring her of, soe the mandarine thinking himselfe wiser than him and his mates in this extreamity, made the Seamen to worke night and day till they were almost spent and would have the Ship haled of by force, which to please him wee did try though to no purpose for the ship presently [….].

Soe wee feare wee must of necessity stay here this spring. now wee looked very solitary one upon another and began to thinke upon his extraordinary ernestness to get the ship yet further up the river, and what it should signifye, but that he might have a better opportunity to ransacke us which makes us esteeme ourselves in no better condicion then a prize.

Gyfford’s cargo consisted of fifty-three bales of cloth, 257 piculs of lead, ten cannon, sixteen chests of brimstone, 618 piculs of pepper, 159 piculs of sandalwood, thirty-eight bales of medicinal plants, eight packages of sundries and ten thousand rials of eight. Out of this, the Tonkinese demanded for the king, ‘without price, manner or tyme of payment,’ seventeen bales of cloth, 150 piculs of lead,seven cannon, twenty piculs of brimstone, six piculs of medicinal plants and some sundries. Threatening force, one officer demanded half the money on board although, ultimately, he was bought off with a bribe of one hundred rials, some pieces from a shaving kit and a three-barrelled pistol.

The grasping continued. Mandarins demanding gifts were put off with bottles of wine, sword blades and knives ‘for feare of the ill consequence that might fall out at Courte.’ On 9 July, representatives of the king’s eldest son pressed for gifts equivalent to half those surrendered to his father. On 24 July, there followed further demands from the king and his third son. Gyfford complained that the mandarins’ promises of ‘service’ served only to give trouble. When the factors were finally summoned to Cachao to see the king and settle the price for his goods, they were offered a figure that covered just a third of their cost.

When, at last, on 7 August, the Zant was permitted to leave, the season was too far advanced. Taiwan was never obtained. (The ship was subsequently blockaded in Java, by the Dutch.) In the letter he sent with her, Gyfford expressed the hope that the factors in Taiwan and Japan had encountered fewer difficulties than he. Summarising his experience, he wrote that, after he had miraculously overcome the danger at the bar,

… the mandarin visited us who tooke a particular Account of all our Goodes, the names and number of our men and how many Guns, tooke away what he pleased from us for the king and princes presents (they being gone to warr against the Couchin Chynese) as alsoe for a number of other mandarins and Secretaries and so ransackt our Ship at his pleasure carrying away all our English Cloth Stuffes, Leade and Guns or anything else … that we hoped to make a profitt by, and told us the king would buy them which is true but it will be at his owne rates and in the acting of this villainy he gave us such excessive trouble that we cannot relate it to you.[12]

Subsequently, for the goods the English wished to purchase, the Tonkinese demanded prices which were guaranteed to produce losses. (For silk, they were forty per cent higher than elsewhere.) Demand for English goods was not as had been hoped for and, increasingly, the factors had to pay for their purchases in specie. As the silver awaited from Japan failed to arrive, sourcing produce became next to impossible – excepting, that is, ‘gifts’ from the king, depending on how generous he chose to be.[13]

The ‘proud and covetous’ Trinh Gyfford found corrupt and avaricious. Sales depended on officials, who demanded bribes, fixed prices, and defaulted on their debts. A favourite trick was arbitrarily to adjust the rate at which cashes (the Chinese coins with a square hole at their centre) were valued per tael of silver. On one occasion, in 1680, the king sent word ‘that he had ordered to pay Cashes for said Goods at the rate of 1500 Cashes per Tael, whereas the current rate of Exchange was 2200 Cashes per Tael.’ (The factors obtained 2,000 cashes.) Two years later, they ‘Exchanged Plate; nett 100 Taile; at 13,500 per Bar, is 135,000 Cass.’ In other years, the king had ‘abated on every ten Tale Plate one thousand Cashies.’

In June 1676, Gyfford was dismissed from his post and recalled to London to answer charges of mismanagement and private trade. Of these he was acquitted (in 1681, he became Agent at Madras). In Tonkin he was replaced by Thomas James. Trade remained difficult. In 1679, Bantam was informed,

Most of the old Debts are desperate. And so some will annually be, since we are compelled to have to do with the King and his Court … the Persons who are Debtors to us are such that we dare not deny them.

In 1681, the factors expressed their pessimism that ‘the natives will hardly ever be brought to make any proper silkes for the trade in Europe.’ The Dutch, they explained, had tried for years to obtain silks of better quality, and in different dimensions, ‘but could never accomplish it.’ In 1682, they wrote:

If your Honours finde noe encouragement in the expence of knowne Manufactories of this Port, in England; from hence wee can give none. And ife you should withdrawe this Factorie all our expence would be quiett lost; and truly with submission to your judgements, wee cannott apprehend this trade worth following any longer.

In 1683, the factory moved upriver to Cachao, from where its reach into the interior improved. It maintained its operations, while the Company decided what to do. One faction, supported by the agent in Bantam, Henry Dacres, was quickly persuaded that, absent a market in Japan, Tonkin could serve no useful purpose. Others believed that the Japanese brush-off might prove temporary. Dacres was far from convinced. To him, Taiwan, which, by 1676, had established links with Fuzhou, in China, was much the greater priority. Even so, he conceded that, by comparison with Siam, Tonkin had the advantage of being able to supply silk for Europe. This it did in increasing quantities until the mid-1680s. Thereafter, as China relaxed its ban on maritime trade, Cantonese product became more plentiful. Tonkin’s role as an intermediary port diminished, even as China assumed a greater importance than Japan in the minds of the Directors. In 1697, the factory was closed.[14]

Samuel Baron’s Description of Tonkin (1678-1683)

We have two accounts of Tonkin in English from this later time: the ‘Description’ of Samuel Baron (1685) and William Dampier’s ‘Voyage’ (1688).

Of Samuel Baron’s personal life, not a great deal is known. His father, Hendrik Baron, was an employee of the VOC, who had headed its operations at Fai-fo. He died as chief factor in Cachao, in 1664. Baron declares himself to be a ‘native’ of Tonkin and it is quite possible that his mother was Tonkinese. This would not have surprised William Dampier, who wrote,

Even the great Men of Tonquin will offer their Daughters to the Merchants and Officers, though their Stay is not likely to be above five or six Months in the Country: neither are they afraid to be with Child by White Men, for their Children will be much fairer than their Mothers, and consequently of greater Repute, when they grow up, if they be Girls … [They] themselves also will prove afterwards obedient and faithful Wives. For ‘tis said, that even while they are with Strangers, they are very faithful to them; especially to such as remain long in the Country, or make annual Returns hither, as the Dutch generally do.

Many foreigners, he observed, had done well by entrusting the care of their money and goods to Tonkinese wives, as they were in a better position to watch the market, buying and selling when prices worked to their advantage.[15]

Quite what caused Samuel to switch his allegiance from the Dutch is unclear. Regardless, his experience was appreciated, as he was in Europe in 1670-1671, when he influenced London’s decision to favour Tonkin for a factory. Because he was appointed to be second in Japan in the voyage of 1672, he sailed to Taiwan, rather than with Gyfford on the Zant. Even so, he dedicated his ‘Description’ to the factory’s first chief,

… since yourself was the first English man that, entring the country, open’d that trade, and settled there a factory for the honourable company; in effecting which your patience appear’d no less exemplary (having suffer’d strange rudeness and harsh usages from the natives, their usual welcome to new-comers) than your prudence and dexterity was eminent in that negotiation, wherein … your generosity respected the honour of your nation and common benefit much more than your particular interest …

Baron may have provided evidence in support of Gyfford at his London hearing, as his name appears in Robert Hooke’s diary regularly over the summer of 1677. Certainly, he was sympathetic to the difficulties Gyfford faced and he is clear that Gyfford ‘chiefly supported’ the publication of his account.[16]

In the event, Baron did not sail to Japan. The onward voyage was delayed until June 1673 and, in the interim, he was charged with taking the junk Camel to Bantam. In its approaches, he was captured by the Dutch. After his release, he became something of a free agent, competing with Chinese merchants. They created trouble for him on at least two occasions. In the first, Baron was stranded on an islet, a short distance into a voyage to Siam, and obliged to complete the journey (in twenty-three days), in a small boat ‘sew’d together with rattans.’ In 1683-1684, he persuaded King Narai to give him charge of a voyage to Tonkin. According to the Englishman Peter Crouch, he fell victim to some Chinese supported by the Company’s antagonist Constant Phaulkon. Crouch wrote that, upon Baron’s return, they ‘procured the losse of his passage … with the expence of 7000 dollers besides the delivery of the greatest part of the King’s concernes into theyr hands.’ With Phaulkon’s encouragement, the Chinese ‘accused [Baron] to the King soe highly that it was resolved to ceaze him as soone as he came into the river.’ Even so, on Crouch’s departure, Baron remained behind. He used the support of the French bishop, who enjoyed the king’s favour, to overcome Phaulkon’s invective.[17]

He returned to Madras in July 1685, having repaid Phaulkon by writing an excoriating report on his activities to Gyfford, then Fort St. George’s president. In his turn, Gyfford appointed his friend to the Amoy council, though he was obliged to reverse his decision, when London refused to support a man whom they characterised as ‘a deserter’ and ‘an expensive extravagant wanderer.’[18]

In addition to repaying his debt to Gyfford, Baron explains he was motivated to write his account by a request from Hooke to correct ‘imperfections and errors’ in the Relation of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, which was translated into English, in 1680. Baron termed Tavernier’s account ‘as fabulous and full of gross absurdities as lines,’ before insisting his intention was to use his personal knowledge ‘to inform the reader of the truth, and not to carp and find faults with others.’

He begins by suggesting that Tonkin was little known, despite having been long visited by the Portuguese, because ‘the people did never stir abroad.’ ‘Nor do they yet,’ he adds, ‘for commerce or other association; and they somewhat affect in this the Chinese vanity, thinking all other people barbarous, imitating their government, learning, characters, &c. yet hate their persons.’ Yet Cachao was a city of consequence, with a large population, particularly on market days, which were held twice a month. Then,

… the people from the adjacent villages flock thither with their trade, in such numbers, as is almost incredible … Every different commodity sold in this city, is appointed to a particular street, and these streets again allotted to one, two or more villages, the inhabitants whereof are only privileged to keep shops in them, much in the nature of the several companies or corporations in European cities.

He concedes that, in his time, the royal palaces, though large, were of ‘mean appearance’, being built of wood. Most other buildings were constructed of bamboo and clay. Yet, in a previous era, he argues, the city had been altogether more impressive:

Stupendous indeed are the triple walls of the old city and palace; for by the ruins they appear to have been strong fabricks with noble large gates, paved with a kind of marble; the palace to have been about six or seven miles in circumference; its gates, courts, apartments, &c. testify amply to its former pomp and glory …[19]

The Le king, Baron explains, was once deposed by Mac, a man of low and vile origin, ‘a wrestler by profession, and so dextrous therein, that he raised himself to the degree of a Mandareen, or lord.’ In due course, the king found champions (the Trinh) who restored him to his throne. But he ruled ‘with the bare name of king,’ as the Trinh reserved the real power for themselves. So much so, in fact, that the titular monarch (‘Bova’) was confined to his palace, with none but the spies of the ‘Chova’ for company:

… he serves only to cry Amen to all that the general doth, and to confirm, for formality sake, with his Chaop, all the acts and decrees of the other; to contest with him the least matter would not be safe for him; and though the people respect the Bova, yet they fear the Chova much more, who is most flatter’d because of his power.

On the other hand, Baron argues that Tonkin’s tyrants were perhaps unique in history in having permitted the true heirs of the king to survive, after they had been stripped of their authority:

We may say … those qualities proper to tyrants, as ambition, covetousness and cruelty, this last was never found prominent in them; whereof [the Bova’s] brothers, who are often intrusted with important employs, as governors of provinces, the conduct of armies, &c. are both convincing proofs and manifest arguments. They are in short too generous to follow the maxim of killing them for their own imaginary security.

He also commends the Tonkinese for preserving the country’s statutes and constitution, for promoting worthy politicians to key positions, and for rotating them frequently.[20]

There were two principal problems. One was the cost of the army. Tonkin’s 140,000 soldiers were a principal reason why the vast sums taken in taxes, head-money, and impositions on foreign trade, benefited the country so little. Yet the soldiery, paid just three dollars a year, were dejected, and far from formidable:

… hardly one in a thousand riseth to preferment, unless he be very dextrous in handling his weapons, or so fortunate as to obtain the friendship of one great Mandareen, to present him to the king: Money may likewise effect somewhat, but to think of advancement by meer valour, is a very fruitless expectation, since they rarely find occasion to meet an enemy in open field, and so have no opportunity to improve themselves or display their prowess …

Baron had a low opinion of the fighting proficiency of the Tonkinese, for all of their recent practice in the art:

Their wars consist in much noise and great trains; so they go to Cochin-China, look on the walls, rivers, &c. and if any disease or sickness happens amongst their army, so as to carry off some few of their men, and they come withing hearing of the shouts of the enemy, they begin to cry out, A cruel and bloody war, and turn head, running, re infecta, as fast as they can home. This is the game they have played against Cochin-China more than three times, and will do so in all probability, as long as they are commanded by those emasculated captains called Capons.[21]

The ‘capons’ for whom Baron reserves his greatest bile are the court eunuchs. These ‘pests of mankind’, the ‘parasites’, ‘sycophants’ and ‘perverters’ of the princes, of whom there were four or five hundred, were detested by all. They were deemed by the superstitious Tonkinese to be destined for great eminence because they had ‘lost their genitals by chance, having had them bit off wither by a hound or dog’:

But it is certain, the general respects his own present profit (whatever the consequence may be) in the advancing of them; for when they die, the riches they have accumulated by foul practices, rapine and extortion, fall in a manner, all to the general as next heir; and tho’ their parents are living, yet in regard they contributed nothing to their well-being in the world, but to geld them, to which they were prompted by great indigence, and hopes of court preferment, therefore they can pretend to no more than a few houses and small spots of ground; which also they cannot enjoy but with the good-liking and pleasure of the general.[22]

Thus, the second blight on the country, corruption. The custom of selling offices to those who offer to pay the most for them was, says Baron, ‘a foul merchandise, and a baseness unbecoming the public.’ Although the laws had been properly codified, the passage of time, and the swelling in the population of petty officers, meant that ‘for money most crimes will be absolved’:

Justice thus betray’d and perverted even by its officers, has brought the country into much disorders, and the people under great oppressions, so as to be involv’d in a thousand miseries; and woe be to a stranger that falls into the labyrinths of their laws, especially into the clutches of their capon Mandareens to be judges of his particular affairs; for to them it commonly happens in the like cases that matters are referr’d, and he must look for nothing less than the ruin of his purse, and be glad if he escapes without being bereav’d of his senses too.[23]

Expressing a sentiment with which Gyfford would have concurred, Baron goes on to explain that corruption made trade in Tonkin a challenge for all:

… no certain rates on merchandizes imported or exported being imposed, the insatiable Mandareens cause the ships to be rummaged, and take what commodities may likely yield a price at their own rates, using the king’s name to cloak their griping and villainous extortions; and for all this there is no remedy but patience.

It was small consolation to know that the Tonkinese were ‘not altogether so fraudulent, and of that deceitful disposition’ as the Chinese. (Baron had not forgiven the latter for their treatment of him.) He regretted that Tonkin’s business was transacted on three to four months’ credit, which meant ‘you run the hazard to lose what was so sold, or at least to undergo a thousand troubles for the recovery of the debt.’ Yet this difficulty sprang from indigence rather than ill-will. A Tonkinese, he wrote,

… will beg incessantly, and torment your purse sufficiently, if you have business with him; whereas a Chinese is cruel and bloody, maliciously killing a man, or flinging him in the sea for small matters.[24]

For the mass of the Tonkinese, Baron had mixed sympathies. He deprecates their use of tones, which meant ‘sometimes twelve and thirteen several things are meant by one word,’ and their custom of not wearing shoes, though ‘this is not observed so strictly as formerly.’ Both sexes were ‘well proportioned’, though of ‘small stature and weak constitutions, ocassion’d, perhaps, by their intemperate eating and immoderate sleeping.’ They were studious, and quick learners. However, though not given to ‘choler’, they were ‘of a working and turbulent spirit, (tho’ cowards) than naturally mild and peaceful.’ That is why the prince kept them poor and needy. Not without reason, Baron adds, for if they were not kept on a tight rein, they would often forget where their duty lay.

Finally, Baron counsels that the Tonkinese were ‘much addicted to the passions of envy and malice.’ By this, he meant their tastes were fickle, their fashions changeable. As a result, whereas formerly they had a taste for new, foreign products, now it was almost worn out, and they were tempted only by gold and silver pieces from Japan, and broadcloth from Europe.

He concludes his comments on the prospects for trade with a note of caution:

In fine, ‘tis pity so many conveniences and opportunities to make the kingdom rich, and its trade flourishing, should be neglected; for if we consider how this kingdom borders on two of the richest provinces of China, it will appear, that with small difficulty most commodities of that vast empire might be drawn hither, and great store of Indian and European commodities, especially woollen manufactures might be vended there; ‘twould be vastly advantageous to the kingdom; but the Chova (jealous that Europeans should discover too much of his frontiers, by which certainly he can receive no injury) has, and will probably in all time to come, impede this important affair.[25]

William Dampier’s Voyage (1688)

Unlike Baron, William Dampier was a short-term visitor to Tonkin. In May 1688, he had reached Achin after a perilous voyage by canoe from the Nicobars, in which two of his companions perished. The dysentery from which he was suffering was to afflict him for a full year. Nevertheless, he was determined to find ‘some employment or expedition, whereby I might have a comfortable subsistence.’ Anthony Weltden, recently returned from Mergen, offered to take him, in the Curtana, to Tonkin, to purchase a sloop for a voyage to Cochin China. This did not eventuate, but Dampier spent some months in Cachao, of which he left an account resembling that of a tourist.

The incident for which it is best known occurred when Dampier inadvertently mistook a large accumulation of people about a ‘slightly built’ tower, for a market:

I came to the Flesh-Stalls, where there was nothing but Pork, and this also was cut into Quarters and Sides of Pork: I thought there might be fifty or sixty Hogs cut up thus, and all seemed to be very good Meat … [I] took hold of a Quarter, and made Signs to the Master of it, as I thought, to cut me a Piece of two or three Pound. I was ignorant of any ceremony they were about, but the superstitious People soon made me sensible of my Errour: For they assaulted me on all Sides, buffeting me and renting my Cloaths, and one of them snatched away my Hat.[26]

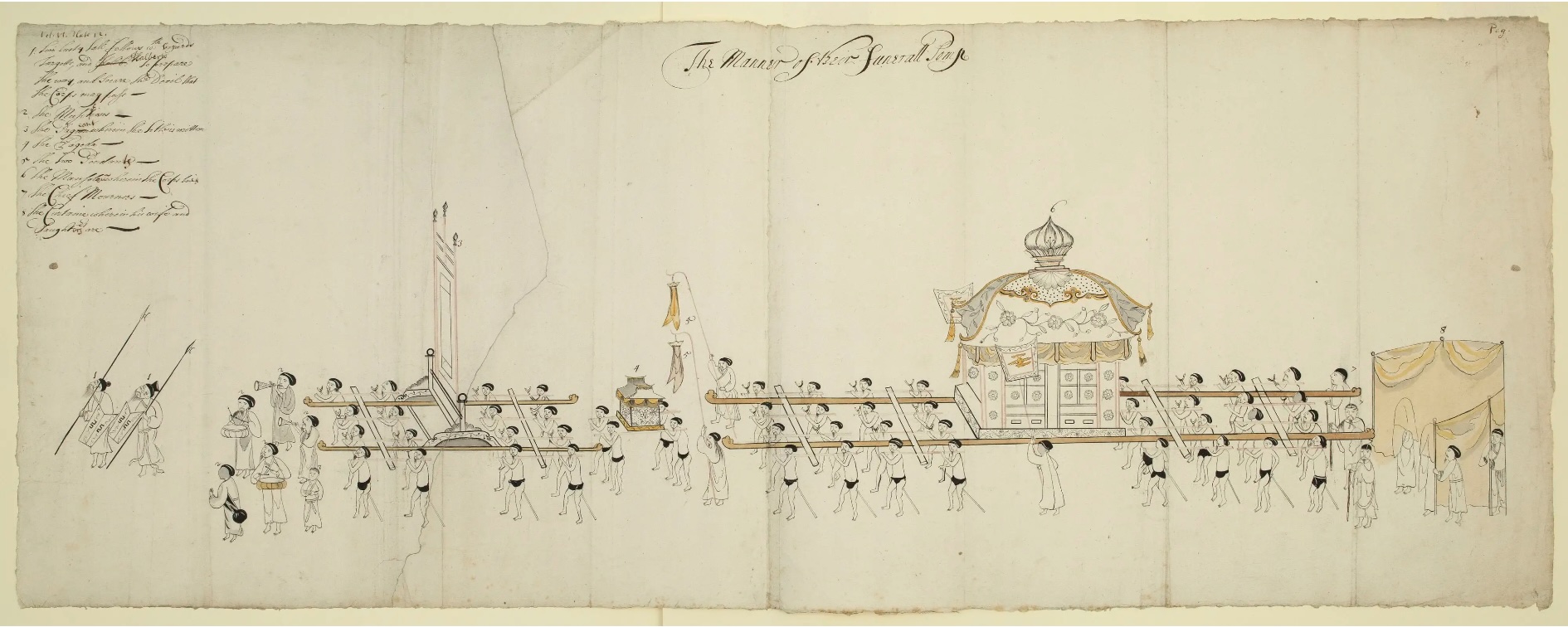

He discovered he had interrupted a funeral feast, and that the tower was a ‘tomb’ that was soon to be set alight …

Initially, Dampier had sailed up the Red River to a point some three miles beyond Domea:

We found not one House near it: yet our ships had not lain there many Days before the Natives came from all the Country about, and fell a building them houses after their fashion; so that in a Month’s time there was a little Town built near our anchoring Place. This is no unusual thing in other parts of India (the Indies), especially where Ships lye long at a place, the poorer sort of Natives taking this Opportunity to truck and barter; and by some little Offices, or Begging, but especially by bringing Women to let to hire, they get what they can from the Seamen.’[27]

He next passed the ‘considerable’ town of Hien (‘Hean’), which he estimates had two thousand houses:

Here is one Street belonging to the Chinese Merchants. For some Years ago a great many lived at Cachao; till they grew so numerous, that the Natives themselves were even swallowed up by them. The King taking Notice of it, ordered them to remove from thence, allowing them to live any where but in the City. But the major Part of them presently forsook the Country, as not finding it convenient for them to live any where but at Cachao; because that is the only Place of Trade in the Country, and Trade is the Life of a Chinese.[28]

The river at Cachao was as broad as the Thames at Lambeth yet, in the dry season, it was fordable on horseback. The country offered ‘all Necessaries for the Life of Man,’ in particular,

… Mulberry Trees in great Plenty, to feed the Silk-worms, from whence comes the chief Trade in the Country. The Leaves of the old Trees are not so nourishing to the Silk-worms, as those of the young Trees; and therefore they raise Crops of young ones every Year, to feed the Worms: for when the Season is over, the young Trees are pluckt up by the Roots, and more planted against the next Year; so the Natives suffer none of these Trees to grow to bear Fruit.[29]

The Tonkinese Dampier thought the ‘fairest and cleanest’ of any of the people he encountered of a ‘tawny Indian colour.’ They were dextrous, nimble, diligent and, to judge by quality of their silk and lacquer work, ingenious. They were also ‘low spirited’, because of their ‘arbitrary government’. Many were ‘extreme poor’, for want of employment, except when foreign ships visited and, by offering credit, supplied them with the capital they lacked.

As elsewhere in the Indies, the Chinese among them were addicted to gaming, to the extent that,

… after they have lost their Money, Goods and Cloaths, they will stake down their Wives and Children: and lastly, as the dearest Thing they have, will play upon tick, and mortgage their Hair upon honour: And whatever it cost them they will be sure to redeem it. For a free Chinese as these are, who have fled from the Tartars, would be as much ashamed of short Hair, as a Tonquinese of white Teeth.

He explains,

Their Teeth are as black as they can make them; for this being accounted a great Ornament, they dye them of that Colour, and are three or four Days doing it. They do this when they are about twelve or fourteen Years old, both Boys and Girls: and during all the Time of the operation they dare not to take any Nourishment, besides Water, Chau, or some liquid Thing, and not much of that neither, for fear, I judge, of being poisoned by the Dye, or Pigment.[30]

On the Tonkinese diet, Dampier is non-committal. The rivers were full of fish, shrimps, and a kind of ‘locust’, which the people skimmed off the surface and broiled on coals, or pickled. ‘Balachaun’ (belacan) was ‘a Composition of a strong Savour’ made from shrimps and small fish pickled in salt. Although ‘rank-scented’, the taste was not altogether unpleasant. ‘Nuke-mum’ (nuoc mam), made from the poured-off liquor, was ‘inclining to grey’, ‘savory’ and used as a sauce by Europeans as well as natives, ‘who esteem it equal to soy.’ Other dishes, including raw pork wrapped in leaves, or beef steeped in vinegar, he declared ‘would turn the Stomach of a Stranger.’ He notes:

The King having a great Number of tame Elephants, when one of these dyes, ‘tis given to the poor, who presently fetch away the Flesh, but the Trunk is cut in Pieces, and presented to the Mandarins. Dogs and Cats are killed presently for the Shambles, and their Flesh is much esteemed by People of the best Fashion, as I have been credibly informed.[31]

Arrack had ‘an odd nasty Taste’ but was much esteemed, for its strength, when the Tonkinese devoted themselves to ‘Mirth, or Madness, or even bestial Drunkeness.’ Infused with snakes or scorpions, it was reckoned a ‘great Cordial’ and an antidote to leprosy.

Most of these Dampier tried. On one occasion, however, he felt compelled to refuse a host’s offer of a meal:

… my Friend, that he might the better entertain me and his other Guests, had been in the Morning a fishing in a Pond not far from his House, and had caught me a huge Mess of Frogs, and with great Joy brought them home as soon as I came to his House. I wonder’d to see him turn out so many of these Creatures into a Basket; and asking him what they were for? he told me, to eat: but how he drest them I know not; I did not like his Dainties so well as to stay and dine with him.[32]

Most Tonkinese houses were of mud and thatch. Each had a small arched construction, like an oven, used to store valuables in case of fire. To guard against the risk, in the dry season, every house was required to have a tank of water on its roof and every owner a long pole, used to cut the straps holding their peculiar panels of thatch in place. Anyone found without his jar upon his roof, and his bucket-pole and long hook at his door, was severely punished. (The streets had plenty of night watchmen, armed with staves, who might ‘dextrously break a Leg or Thigh-bone, that being the place which they might commonly strike at.’)[33]

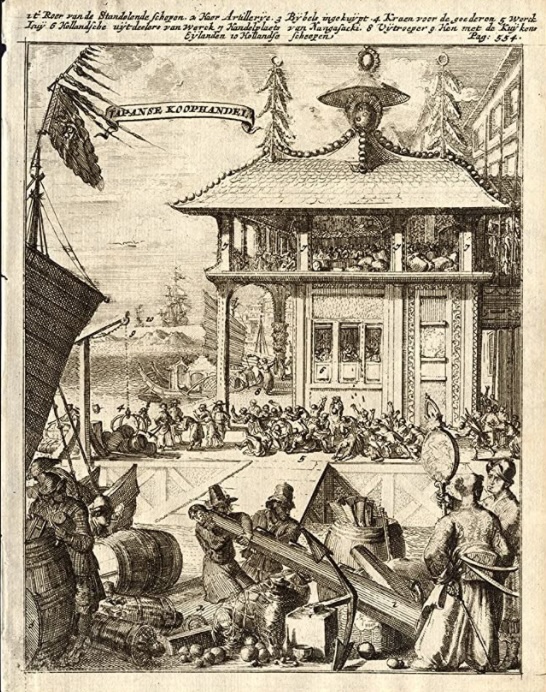

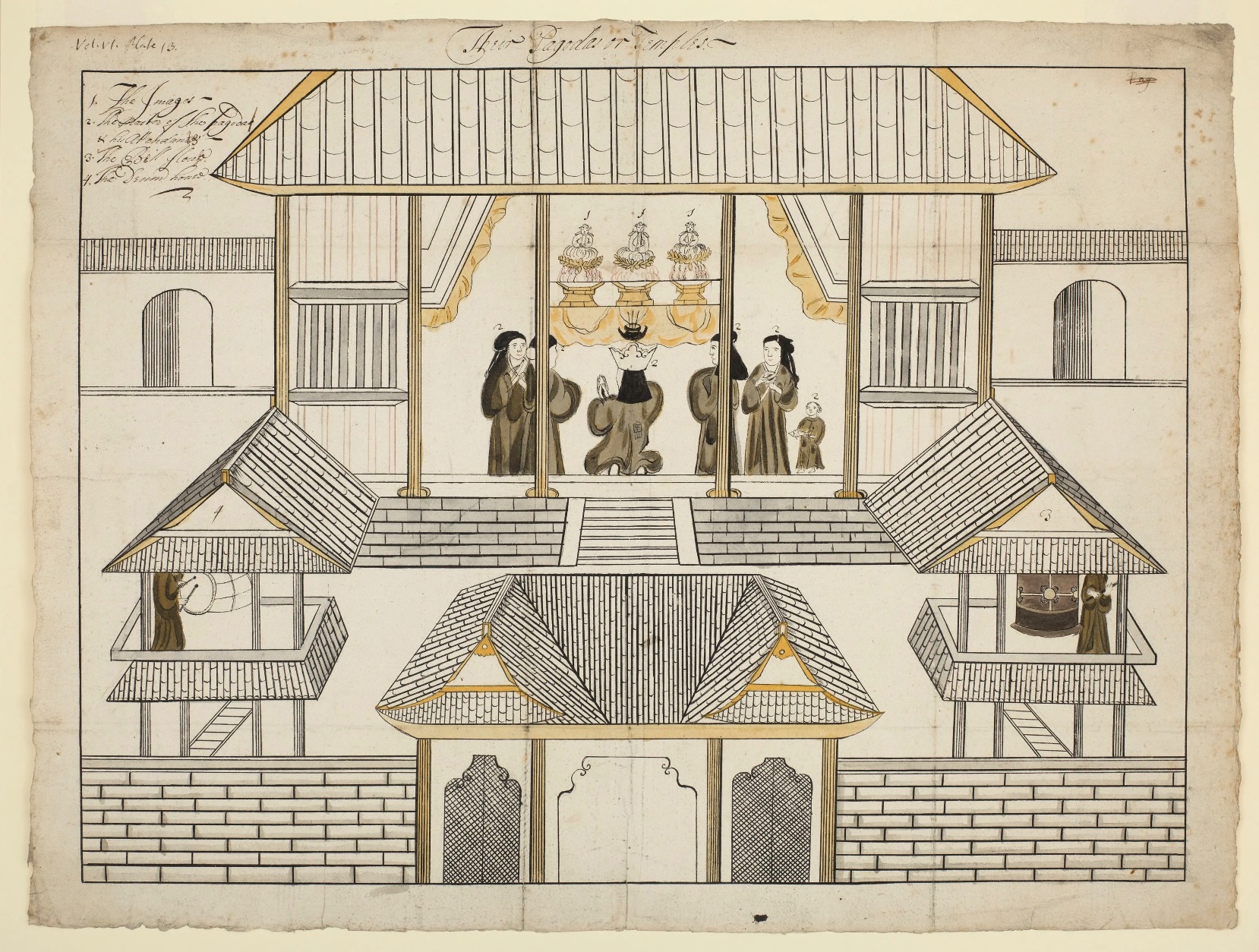

One building that stood apart was the English factory. The Company had negotiated for ten years before permission was granted for its construction – a prize well worth securing, for, as Dampier himself appreciated, Hien was no match for Cachao as a centre of commerce. (Cachao, he suggested, was one of the largest cities in Asia, with an estimated twenty thousand houses.) As an illustration in Baron’s account shows, the factory stood opposite the VOC’s establishment, was conveniently close to Court, and, at its centre had a handsome open area fronting the river. With some pride, Dampier noted,

In this square space, near the Banks of the River, there stands a Flag Staff, purposely for the hoysting up the English Colours on all Occasions: for it is the Custom of our Countrymen abroad, to let fly their Colours on Sundays, and all other remarkable Days.[34]

Less impressive was the Company’s chief factor, William Keeling. When he persuaded the Tonkinese that some bells, ordered by Constant Phaulkon for the French churches in Siam, should be offloaded from the Curtana, Dampier thought it ‘a very strange action,’ although England was then at war with Siam, as he and Weltden knew. In Dampier’s opinion,

[Keeling] was a Person but meanly qualified for the Station he was in. Indeed had he been a Man of Spirit, he might have been serviceable in getting a Trade with Japan, which is a very rich one, and much coveted by the Eastern People themselves as well as Europeans. For while I was there, there were Merchants came every Year from Japan to Tonquin; and by some of these our English Factory might probably have settled a Correspondence and Traffick, but he who was little qualified for the Station he was in, was less fit for any new Undertaking …

Dampier was of the view that the Company needed to move beyond the protection of its existing trade, and explore new opportunities:

… it seemed to me that our Factory at Tonquin might have got a trade with Japan: and to China as much as they pleased. I confess the continual Wars between Tonkin and Cochinchina, were enough to obstruct the Designs of making a Voyage to this last: and those other Places of Champa and Cambodia as they are known, so was it more unlikely still to make thither any profitable voyages: yet possibly the Difficulties here also is not so great, but Resolution and Industry would overcome them; and the Profit would abundantly compensate the Trouble.[35]

It happened that, at the time of Dampier’s writing, having abandoned Japan and made China its priority, the Company was on the point of embarking on its first effort at direct trade through Canton. Sent there from Madras, in July 1689, Thomas Yale landed near Hong Kong from the Defence, for negotiations with Canton’s Hoppo, in September. Nevertheless, Dampier’s remarks about Cochin China were prescient.

He had learned from Captain John Tyler of the Cochin Chinese practice of enslaving those who were shipwrecked on their coast. After ‘a considerable Stay,’ Tyler had been sent away on the promise that he would return to trade (which he most disinclined to do). Personal safety aside, he decided that the Cochin Chinese had little to offer. However, he conceded that they had an interest in commerce, and that refugees from the Manchu conquest of China had ‘instructed their kind Protectors in many useful Arts, of which they were wholly ignorant before.’ Optimistically, Dampier surmised, it was probable that opportunities would soon present themselves.

In May 1695, Thomas Higginson, President at Madras, noting that the truce between the Trinh and Nguen had held for twenty years, sent Thomas Bowyear, one of those Dampier met at Cachao, to Cochin China, to investigate the utility of opening a factory. Possibly, he believed, it might reinforce the declining operation at Tonkin.[36]

Thomas Bowyear’s Mission to Cochin China (1695-1696)

Bowyear’s instructions expressly told him not to conclude any contracts; only to make and receive proposals. Of first consideration was the possibility of the Company being granted ground for a factory. Ideally, this was to be ‘within a random shot, wherein a fort may be built’ and, best of all, on a small island.

Thereafter, Bowyear was to inform himself of the following particulars:

The Names and Titles of the King and his Family.

The Names, Titles, and Offices of his Chief Servants and Favourites.

The Manner of Government, especially relating to the Trade of Foreigners.

The Order of the Custom-House.

Whether the King of Cochin-China has War, or Peace, with the Kings of Tonqueen, Siam, and Camboja.

Whether a Trade be driven from thence to Jappan, and by what Merchants? What is the Amount of the Stock and Number of the Vessels yearly? What sort of Goods carried thither? And what brought back? Whether Europe-Cloth may be sent to Jappan by the Cochin-China Junks?

The Prices of all sorts of Commodities growing, or made, in the Country, or imported from any part.

The Trade or correspondence the Dutch have, or had, in Cochin-China, and how the King stands affected to them?[37]

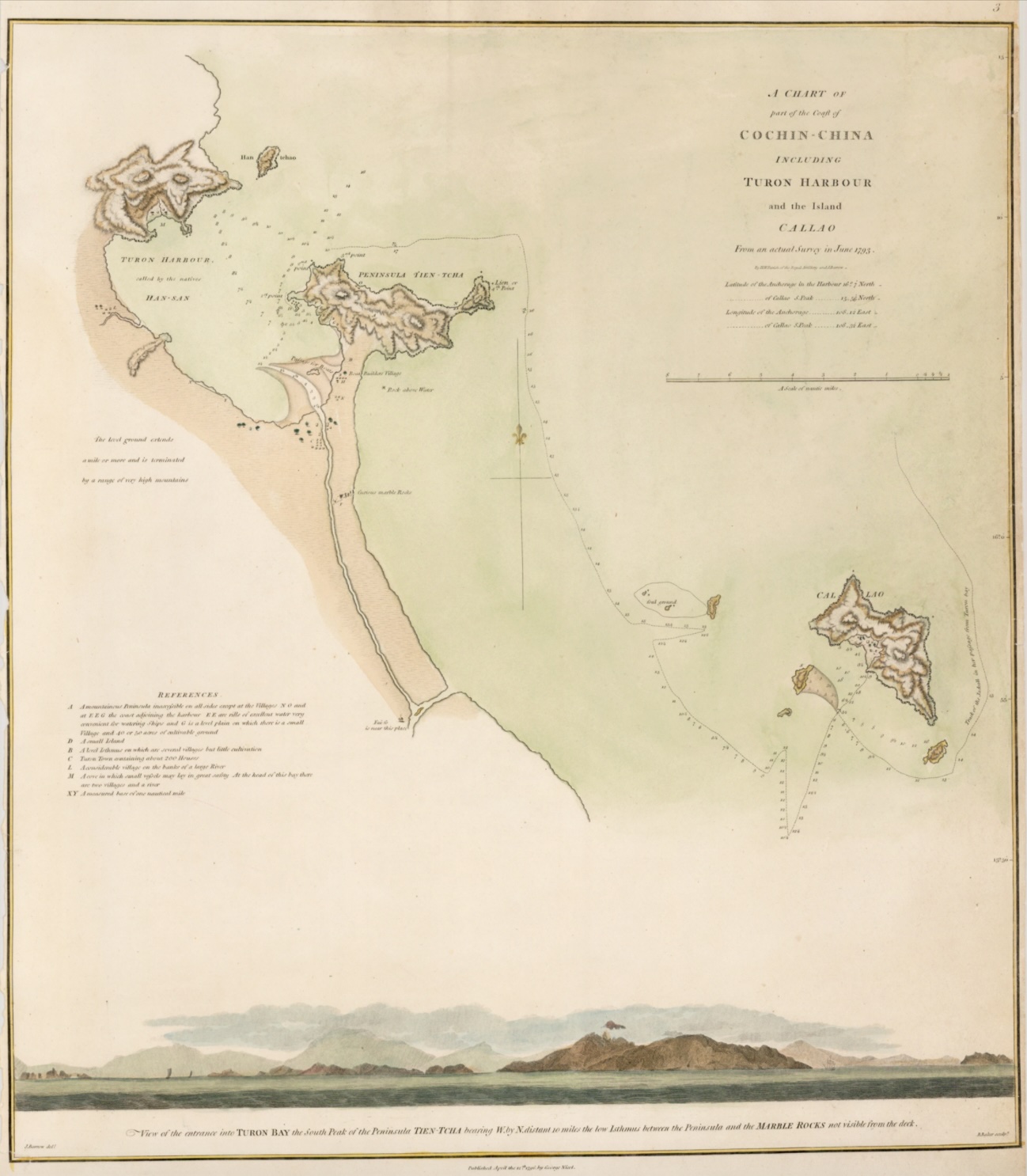

Bowyear’s ship, the Dolphin, anchored off Callao Island (Cu Lao Cham, near Da Nang), on 18 August 1695. It took some while to get help ashore, but this was obtained after three days and, that evening, Bowyear and a Mr. Gyfford (conceivably, Tonkin’s first chief), were entertained by a fisherman with a supper of boiled snake and rice. They were then taken to Fai-fo, where they were received by some officials and a large company of armed men.

… we had a Matt spread to sit on, and after some General Questions, were desired to stand up, that their men might feel us, it being their Custom, which they did, examining our pockets, and after, my Chest, Bedding, and Scrutore (escritoire), opening every particular (sealed Letters excepted, of which they found several for the Padris) as if they searched for Diamonds, &c., a Common-Prayer-Book, and other of like bulk, they must know what was writt in them, and what Language, with many other Impertinencies that I shall forbear particularising, for I fear being tiresome …

As Higginson’s letter to the king was translated into Portuguese, for the padres at Court to interpret, the Dolphin’s cargo was unloaded for inspection. The process took a full twelve days.

Finally, after a five-day journey over the mountains (‘there is a much nearer way, but prohibited, for what reasons I cannot learn’), Bowyear reached Sinoa (Hué), on 9 October. He there discovered the king ‘was entered into his Tongtam, or 8th Moon,’ a time he set apart for recreation, and during which no petitions were accepted. There followed three weeks of wrangling with two foreign trade officials (‘dispatchadores’): Ung Coy Back ‘a good moral Man, and of great moderation,’ and Ung Cokey Thoo, ‘of a hard face, but courteous, smooth and well spoken.’ He offered to manage the Englishmen’s business for five hundred taels (later reduced to one hundred).

At last, on 2 November, Bowyear obtained a first audience, consisting of a simple exchange of gifts:

I was led before him … with a present as customary, which set down about 50 Paces from the King; I there stood, and made my Bows, and retired; after the King had asked, what Captain it was, and given me ‘A ja Ung’, or ‘Thank you Sir’, he sent as customary, to the House where I was, a Present of 10,000 Cashes, a Hog, two Bags of Rice, two Jars of Salt Fish, and two Jars of Wine.

It was only on 27 December that Bowyear was able formally to make his proposals:

The Answer was, that in Case of a Settlement, the Proposals should be granted, and, if I would, might make them Choice of Ground for a Factory, and Ung Coy Back-Looke was ordered to shew me the Guns about the Palace, to know if his Honour could send the King such Guns?

… On this the Customs-House Books were produced, and the king ordered immediately Payment to be made me, which was done for what he took, in Gold, as I desired, but at a high rate; and understanding withall that the King had abated fourteen hundred and odd Tales of the Prices that Ung Cookey had made of our Goods at the Customs-House.

Obtaining payment proved a drawn-out affair. At first, some Japanese traders were appointed as intermediaries, but they pleaded poverty and were excused. On 27 January 1696, ‘the Drum was beat about the Court, giving notice, that whosoever did not make immediate Payment … should lose their Offices.’ Yet, it was only on 17 February that Bowyear felt able to depart. By then he had missed the monsoon. The Dolphin finally sailed at the end of April.

Bowyear does not specify how much he gained or lost in the trading of his remaining cargo, but the tenor of his narrative suggests he thought Cochin China worth pursuing. Fai-fo, he says, traded with ten to twelve junks a year from Japan, Canton, Siam, Cambodia, Manila and Batavia, although he admits that the number of Japanese in the town was much reduced from former times, and that their junks sailed less regularly, following the emperor’s prohibition on the export of silver (1668). Canton, he wrote, supplied cashes ‘of which they make great profit,’ silks, chinaware, tea, tutenague, quicksilver, medicinal roots; Siam, saltpetre, sappan wood, lac, mother of pearl, tin and lead; Manila, silver, brimstone, sappan, cowries and tobacco; and Cochin China, gold, iron, silk, agar wood, sugar, jaggery, birds’ nests, copper and cotton.

The Madras Council were unpersuaded. At the end of May (so before Bowyear delivered his report), they had received instructions from London to abandon Vietnam altogether. (It was a sign of the times that, a few days before, on 4 May, the council had made concessions on a bill of freight given to two traders, to allow for the ‘length and misfortunes of [their] voyage which lasted about two years and a halfe, and the badness of the markett for Tonqueen Goods.’) When ordering the factory’s closure, on 6 March 1695, London’s Directors explained that the trade with China ‘out and home’ was more profitable, as it required no permanent establishment. They also complained of Cachao’s ‘remoteness’. Corresponding with it meant ‘sending a ship which how little so ever they can seldome half load, except by filling her up with mean lackred wares that will not pay half freight.’[38]

However, it was the malfeasance of Tonkin’s former chief factor, William Keeling, that, coupled with the growing conviction about the competitiveness of Chinese silks, finally crystallised their opinion.

William Keeling and the Junk Affair (1693-1696)

Keeling’s advantages were that he had experience of Tonkin since 1672, and important connections at Court. However, he was a divisive character, being one of those who, in 1676, argued that Thomas James, ‘being sickly and crasie’, was unfit to serve as chief. In 1681, he organised a coup against James’s leadership, arguing that he had unwisely invested 33,000 taels of the factory’s silver. Next, he was involved in multiple disagreements with William Hodges, whom he displaced as chief, in early 1683. The loss of Bantam’s oversight after 1682, a decade of support from London, and Tonkin’s isolation during the Nine Years’ War, allowed Keeling to accrue power until 1693, when he was displaced by Richard Watts, sent by Madras, at London’s urging, to investigate a ‘great estate’ in Tonkin of $30,000.

Since 1689, the Directors had been urging frugality. Instead, losses had increased, and the accounts had become threadbare.[39]

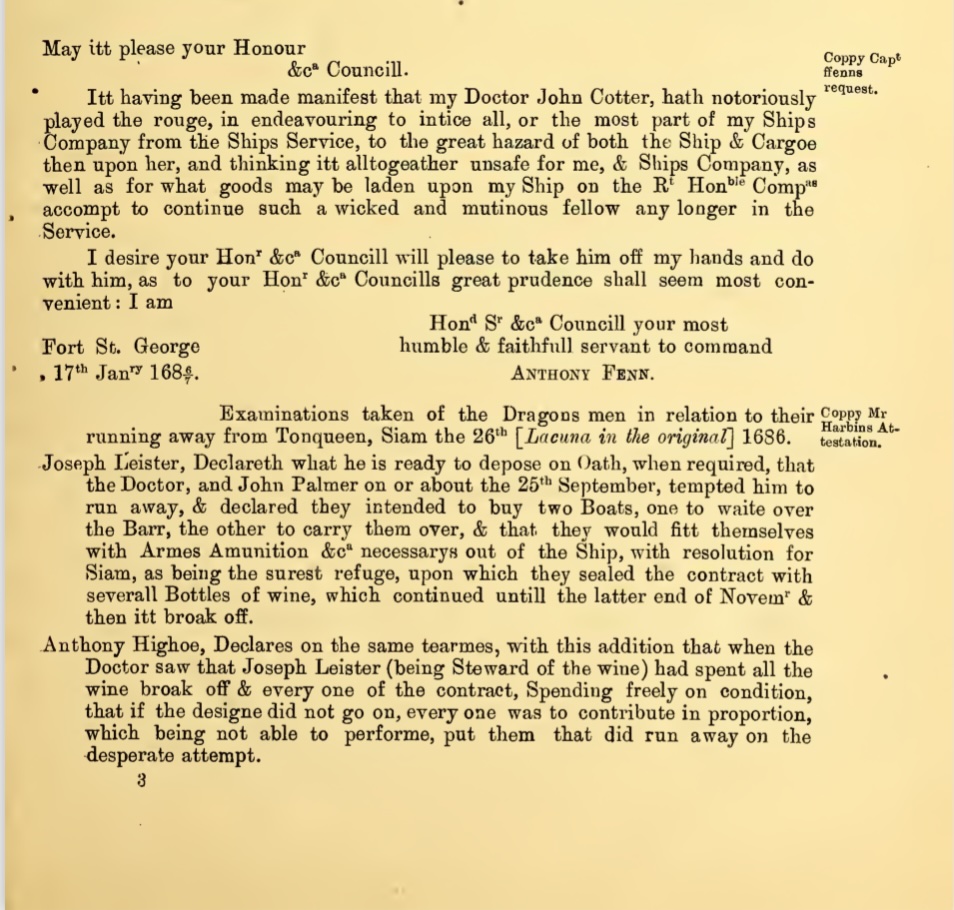

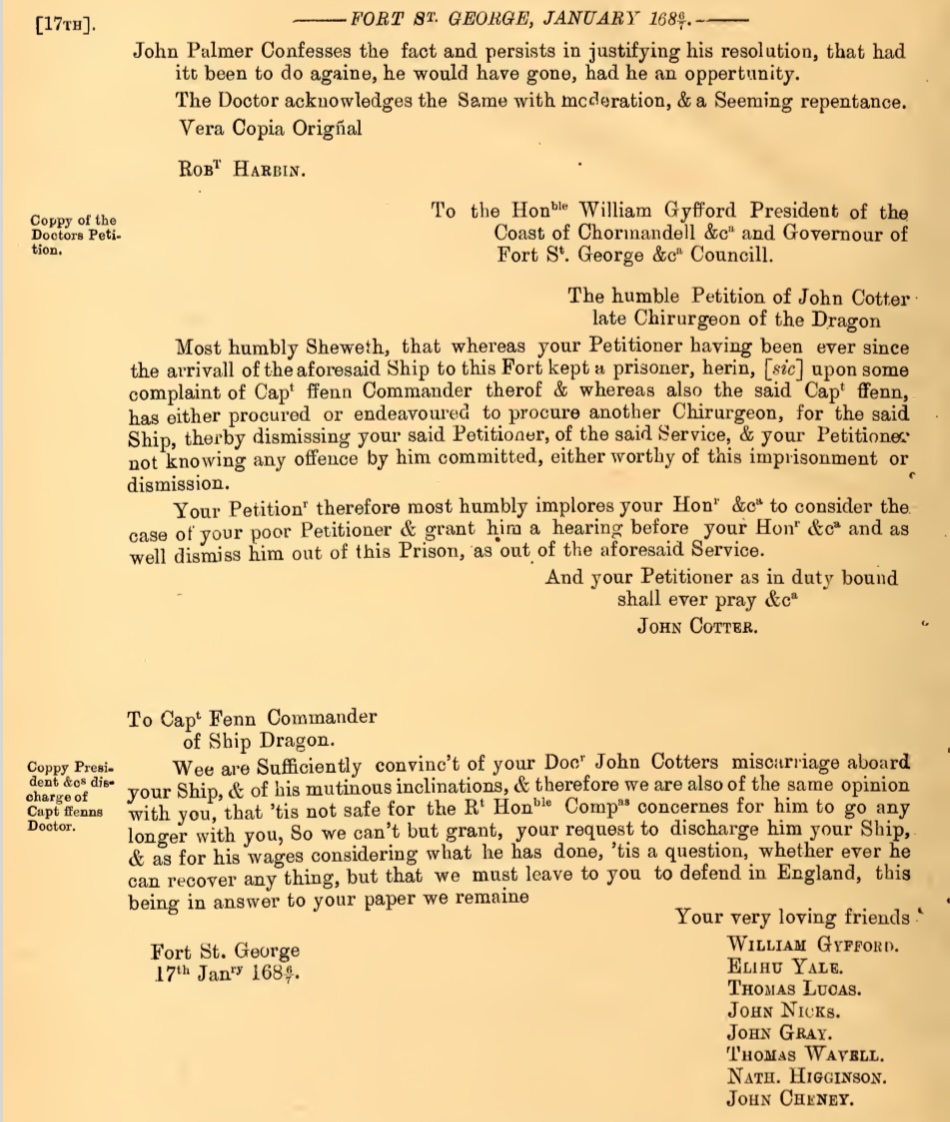

During his outward voyage, Watts chanced upon a junk carrying a substantial cargo owned by Keeling and two of Tonkin’s factors. The junk evaded arrest, and was abandoned, as a loss, off the coast of Cochin China, where its crew were, for a period, imprisoned. (Later, it transpired that the junk had been taken to Hainan.) The imprisonments incensed Tonkin’s rulers, some of whose citizens were their victims. In December 1693, they imposed a maritime embargo. It required that, before leaving, foreign ships were to be inspected, to ensure that they carried no Tonkinese, and no forbidden goods. Immediately, it was appreciated that these inspections would ‘create both charges and a great deale of trouble.’

When he arrived in Tonkin, Watts found that the books, removed to the house in which Keeling lived with his Tonkinese wife, were five years out of date. As a result of embezzlement, the factory had run out of money. The warehouse contained only some worthless iron and lumber. Nevertheless, Keeling utilised the support of the Tonkinese to resist deportation to Madras until 1695.[40]

On 4 June 1696, the Madras Council, in minuting that Keeling had been ordered to supply details about the junk, and about debts owed to the Company by several Tonkinese, reported that,

Hee hath hitherto and now given no other answer but that he hath left all his concern and Papers in the hands of som persons in Tonqueen under such orders that they will deliver nothing except he goes himselfe in person, and refuseth [to disclose] in whose hands the same is left, affirming that he doeth not know himselfe, and tho he hath frequently expressed in discourse in such a Manner that we have suspected he was inclinable to distraction, but upon Consideration of the Cunning disposure of his affairs in Tonqueen to secure them from seizure, and the subtle evasive answers which he frequently gives, it may be suspected that he Counterfeits and designes to make his escape to Tonqueen by the first opportunity.

They initiated an action for twenty thousand taels on behalf of the Company in the Court of Admiralty. Twelve thousand represented their losses on the junk, the balance bad debts, for which Keeling was unable to provide any invoices.[41]

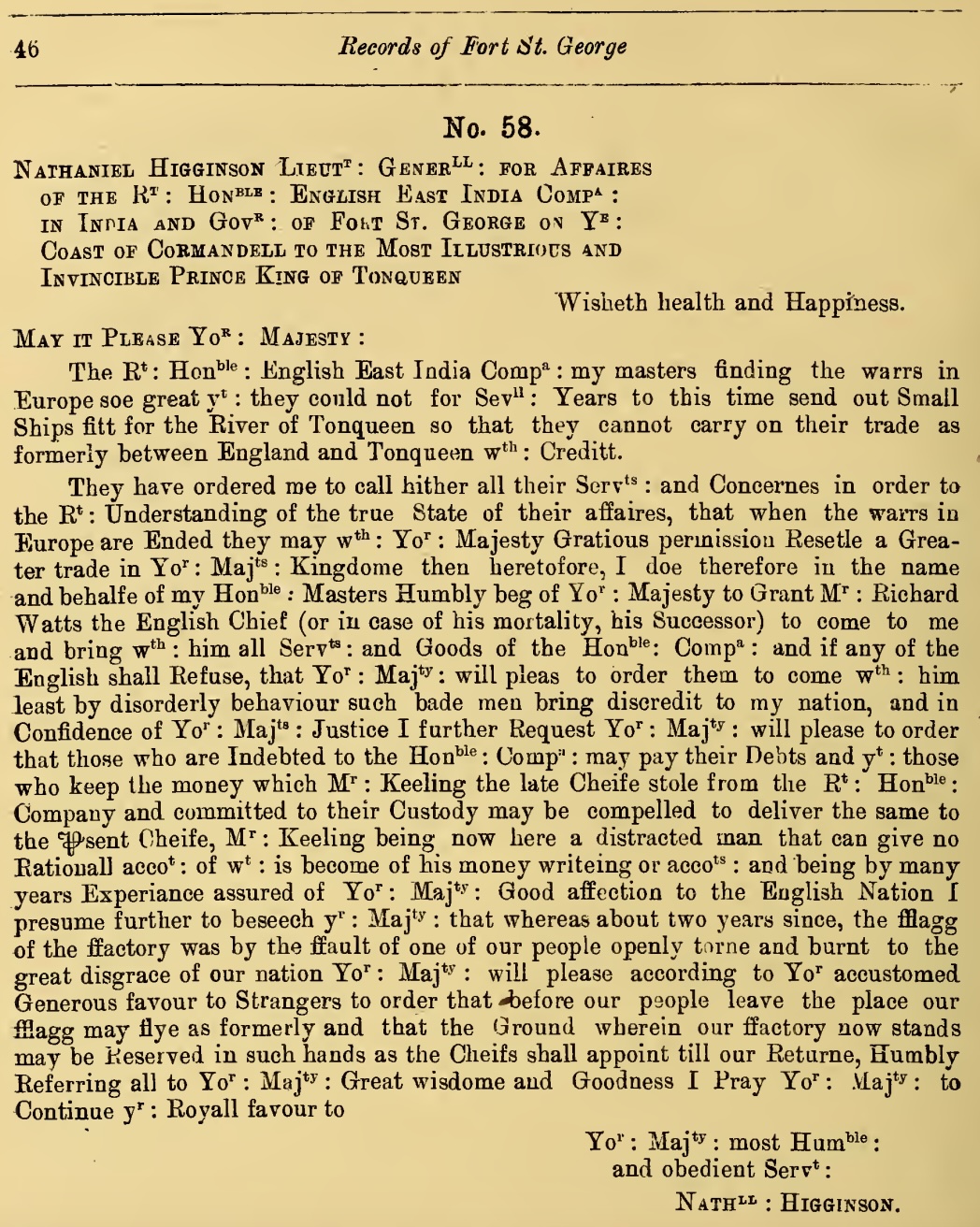

On 30 May, President Higginson wrote to Tonkin’s king. He explained that he was required to close the factory as a result of,

… my masters finding the warrs in Europe soe great that they could not for Severall Years to this time send out Small Ships fitt for the River of Tonqueen so that they cannot carry on their trade as formerly between England and Tonqueen with Creditt.

It was a convenient justification, if an incomplete one. Higginson asked His Majesty, if any of the Company’s servants refused to accompany Watts to Madras, ‘pleas to order them to come with him least by disorderly behaviour such bade men bring discredit to my nation.’ Rather hopefully, he also asked for assistance in obtaining payment for debts due, and to secure the factory for the Company’s ultimate return:

… and being by many years Experiance assured of Your Majesty’s Good Affection to the English Nation I presume further to beseech your Majesty that whereas about two years since, the fflagg of the ffactory was by the ffault of one of our people openly torne and burnt to the great disgrace of our nation Your Majesty will please according to Your accustomed Generous favour to Strangers to order that before our people leave the place our fflagg may flye as formerly and that the Ground wherein our ffactory now stands may be Reserved in such hands as the Cheifs shall appoint till our Returne.

It is not to be imagined that the combusted remains of the English flag would have commanded the admiration of the Tonkinese. It was not needed again.[42]

The Mission of Charles Chapman (1778)

In the period after 1696, the Trinh became more isolationist, even as the prominence of Cochin China increased. The latter’s harbours bordered on the sea lanes connecting the Indian Ocean to the China Sea in a way that Tonkin’s did not, and, as the Nguyen expanded their territories towards Cambodia, they inevitably drew to themselves the attention of Siam and of governments elsewhere in South-east Asia.

The Dutch withdrew from Vietnam in 1700 and, in their place, there emerged the French. They were motivated by more than trade. They were evangelists for the Catholic faith, as they had been at the Siamese court of King Narai, in the 1680s. They also sought to forestall the English from securing a dominant share of the trade with China. French interest in Cochin China picked up from the late 1730s and, in 1753, Joseph Dupleix, Robert Clive’s antagonist in India, sent a mission to establish a factory at Tourane (Da Nang). The advent of the Seven Years War meant this was abandoned, but Cochin China remained a target for French strategists, if only because it was clear of English influence.

‘It seems that there remains only Cochin China which has escaped the notice of the English; but can one flatter oneself that they will delay in casting their glance there?’, wrote the French foreign minister, the Comte the Vergennes, in 1775. Simultaneously, Pierre Poivre was promoting the idea of seizing Callao Island. He knew that the English Company derived much of their profit from the China trade, and that a French base astride the route would pose a material threat. Pressures caused by the American Wars made this plan stillborn. Yet the French knew that, had they acted, the Nguyen would have found it harder to repel them than at any time in the previous century. They were again at war with the Trinh, who had captured Hué and, although the Nguyen retained Fai-fo and Tourane, they were everywhere under acute pressure from the Tay-son rebels, who had risen against the self-proclaimed regent Truong-Phuc Loan, in 1771.

In 1777, the French ship Diligente, sent to Tourane by Jean-Baptiste Chevalier, governor of France’s settlement on the Hooghly River (Bengal), encountered a vessel belonging to the Calcutta firm of Crofts & Kellican. The Rumbold had just beaten off a force of Tay-son galleys, and its captain suggested that the Diligente might combine with him in support of the Nguyen. Captain Cuny declined to get involved. Then, six months later, when the Rumbold drew into Calcutta after a profitable voyage, the French noticed she conveyed into its refuge two important Nguyen mandarins.[43]

On 12 February 1778, Warren Hastings, Governor-General in Calcutta, received a letter from David Kellican:

I beg to inform you that two Mandarines from Cochin China with a Portuguese Missionary are arrived in Calcutta … I take the liberty of requesting your permission, to present the Mandarines to you, whenever it may be convenient, as likewise the Portuguese Missionary. The Mandarines are men of distinction. One of them is a first cousin of the King of Cochin China.

On the very same day, Chevalier wrote to his superior, the governor at Pondicherry, warning,

We cannot conceal from ourselves the conclusion that, if the English send help to Cochin China, they will not delay in becoming masters of the whole country, just as they did in Bengal and in the rest of their possessions in India … If, on the other hand, we anticipate them, this same empire will fall into our hands and will be the glorious fruit of our activity and perspicacity. In the present situation it is inevitable that some European nation will rule over the country, and it will be the nation which first brings help that will win the prize.

Unfortunately for the French, Hastings was not one to let slip his opportunity. He argued that to treat the mandarins humanely, and take them home, would create a favourable impression among their people. At the same time, he informed his council that the French had offered them a vessel. Crofts & Kellican, he explained, were keen to investigate trade with Cochin China and had asked that an official might join their next voyage, so that, with the assistance of the mandarins, they might obtain approval for future undertakings. They were optimistic that they would be able to export products from Europe, as well as from Bengal; more particularly, that in Cochin China they would be able to engage with Chinese sea-going junks and procure returns in gold, silver and pepper.

Hastings reminded the council of the Company’s earlier attempt to establish itself at Balambangan, and argued that Cochin China might serve the same purpose, at a significantly lower cost:

The Company have always had in view the encouragement of a trade with the Chinese junks, this was Mr Dalrymple’s object, when he proposed the Settlement at Balambangan … It is not now intended to subject them to any charge whatsoever, except the trifling one of maintaining a single gentleman as resident in Cochin China, which measure it is hoped may be productive of many of the advantages expected from the prosecution of that unfortunate scheme …

Cochin China is particularly happy in its situation for commerce. Possessing a large extent of coast of its own, it is within five days sail of Canton; has the Philippines laying opposite to it; the great island of Borneo, the Molucca and Bunda islands, a few degrees to the southeast, with Siam and Malacca to the westward. Its many excellent harbours would afford a safe retreat to our Indiamen when they might be so unfortunate as to lose their passage either to or from China …

In conclusion, he said it was prudent to attempt to obtain privileges on terms that were superior to the French (or others),

… and for this purpose I propose that a person be sent … to investigate the real state of their country, its sources for trade … and that he likewise be vested with powers, should he find the state of things answer the expectations formed of them … to form a Treaty of Commerce on the part of this Government with that of Cochin China.[44]

Chapman departed Calcutta, on 16 April 1778, on the snow Amazon, with the senior mandarin, Ong-tom-being. (The junior mandarin sailed on the smaller Jenny and perished on the way.) Off the eastern coast of Malaysia, they encountered some Cochin Chinese refugees who had been shipwrecked and sold into slavery. Whilst the account they gave of the situation in Cochin China was somewhat garbled, their lack of interest in being released was transparent, and an unwelcome portent of what might be expected. Chapman learned that Van-Nhac (‘Ignaac’), the eldest of the Tay-son brothers, was carrying all before him, and that the king of the Cochin Chinese had been put to death on Pulo Condore.

News that a force of Tay-son galleys was operating in the Mekong River persuaded Chapman to take his charge to Saigon (‘Donnai’), where Nguyen Anh, the surviving Nguyen leader, had established a base. Then, an encounter with another miserable group of villagers, taught him that, two months before, the fleet blockading Donnai had,

… plundered them of the scanty remains left by a horrid famine, supposed in the preceding year to have carried off more than one half of the whole inhabitants of Cochin China; and that they had nothing to eat but a root thrown up by the surf on the beach which caused them to break out in blotches all over their bodies.

Now Chapman understood why the refugees at Terengganu had been uninterested in returning home: ‘They were not possessed of sufficient patriotism to prefer liberty with so scanty a fare in their own country to slavery with a full belly in a foreign one.’ Ong-tom-being shared their opinion. As he was being conveyed towards the shore, he seized hold of Chapman and begged him to steer away. ‘All was insufficient to remove his fears,’ declared the Englishman:

What to do, or whither to go I was now at a loss. If I determined to avoid every place in the hands of the enemies or the suspected enemies of our Mandarines I was at once excluded from the whole country and nothing remained but to return without further loss of time to Calcutta. Unwilling, however, or, indeed, rather ashamed to leave Cochin China almost as totally uninformed as when I sailed from Bengal, I resolved at all events to prosecute my voyage as far as the Bay of Turon and eventually even to make a visit to the Court of Ignaac.

In protest, Ong-tom-being, who had been completely unnerved, ‘rushed from his cabin and threw himself upon the ground apparently in the most violent agony.’ Chapman calmed him by reminding him that the preponderance of Ignaac’s fleet were investing Saigon. That meant that fewer ships would be in the port of Qui-nhon (‘Quinion’), where Ignaac had his headquarters. Chapman felt that the action of the Rumbold the year before set a good precedent, particularly as he knew there were some ships from Macao in the harbour. He would solicit an audience to discuss a commercial treaty.

He anchored on 16 July and, three days later, received Ignaac’s invitation and pass of safe conduct. This was brought aboard with great ceremony by some mandarins, who required that the ship’s colours be hoisted, and an umbrella set up, to receive it. Next they hinted that they would welcome some token of appreciation for the trouble they had taken. Chapman gave them a desert of wine and sweetmeats.

Our poor unfortunate Mandarine, who was now on board incog., and the better to conceal himself dressed in an English dress, his beard shaved, his teeth cleaned and, what distressed him most of all, his nails reduced to three or four inches, desiring to see the paper told me with tears in his eyes that the seal affixed was the ancient seal of the Kings of Cochin China, which the villainous possessor had stolen; that the reasons he assigned for seizing the Government were false, for that he alone was the sole author of the calamities his country had and still experienced. He conjured me not to trust myself in his power for I should never return.

Ignaac’s palace stood within a stone wall, three-quarters of a mile square, and in a state of some disrepair. Chapman dismissed his attendants – not so much as a boy with an umbrella was permitted to accompany his party – and they were admitted to the presence, on the morning of 25 July:

In front were drawn up two ranks of men consisting of an hundred each with spears, pikes, halberds &c. of various fashions with some banners flying and from within appeared the muzzles of two long brass cannon. In the middle of a gravelled terrace in front of the palace was laid the presents I had brought. As soon as we ascended this terrace the Mandarine our conductor told us to make our obeisance in the same manner he did, which consisted in prostrating himself three times with his forehead to the ground. This mode of salutation, however, appearing to us rather too humiliating, we contented ourselves with making as many bows after the English fashion.

Dressed in a yellow silken robe and a cap decorated with jewels, one of which danced about at the end of a wire a few inches long, Ignaac was seated on an elevated dais in an open pavilion in the Chinese style. On each side of him were seats for his brothers. Beside them were several rows of benches for the mandarins and, behind these, at some distance from the throne, one for the English delegation. Chapman mentioned that the arrangement was inconvenient for diplomacy and they were brought forward. Then they began.

After answering questions about England’s naval power (accepted), and her tendency to piracy (denied), Chapman asked for trading rights like those granted to the Portuguese, but with fixed fees, to avoid the ‘disagreeable circumstances’ by which others were ensnared by the officers of the ports. These were granted. Immediately, Ignaac raised the matter of greatest moment to himself: ‘whether and upon what terms I would assist him with the vessels I had under my orders against his enemies.’

They retired to Ignaac’s private apartments, where he explained that he planned the conquest of the whole of Cambodia as far as Siam, as well as of those northern provinces of Cochin China in the hands of the Tonkinese. If the English provided him with vessels, he would waive all fees and grant land for settlement. Evidently, Ignaac had been impressed by the performance of the Rumbold, yet it was a novel way of responding to a trade delegation. Chapman said simply he would pass on the message, and begged permission to travel on to Tourane.

To his diary he committed his inner thoughts about the Tay-son ruler :

… like [Nadir Shah], he was the commander of a small fortress in a strong situation from whence he sallied and made a prey of the unwary; like him he grew into consequence at about the same age, and under the pretence of supporting his sovereign made himself master of the throne; like him he declared himself the avenger of the wrongs of his country and became a tyrant more odious and destructive than it had ever before experienced; and like him it is not improbable he may finish his career, at least it will be a reward best proportionable to his merits.

He admitted Ignaac had some ability, but his army was deficient, and the mandarins who supported him were low and illiterate, ‘remarkable only for their perfidy, cruelty and extortion.’ The country was appallingly destitute. Even in Hué, which, being under Tonkinese control, was better supplied, human flesh was publicly sold in the market. Tourane’s governor issued to Chapman a trading licence which enjoined its citizens to pay for what they purchased upon pain of severe punishment. No one had money to spend.

Chapman reached Fai-fo, on 14 August, after a peaceful night’s passage past the limestone outcrops that marked the coast. He was,

… surprised to find the recent ruins of a large walled city; the streets laid out in a regular plan paved with flat stone and well built brick houses on each side. But, alas, there was not little more remaining than the outward walls within which, in a few places, you might behold a wretch who formerly was the possessor of a palace sheltering himself from the weather in a miserable hut of straw and bamboos.

Fai-fo’s governor lived in some style but, to obtain his possessions, he had used duplicity to execute a distant relation of the royal family (his wife and children were bound together and thrown into the river). Chapman was convinced that he obeyed Ignaac’s orders only when they answered his purposes. He stayed just one day.

He next received, through the medium of a Portuguese merchant, an invitation from the Tonkinese viceroy of Hué. Transferring to the Jenny, which was better suited to the shallow waters of the Perfume River, Chapman took with him Ong-tom-being, who had been persuaded that the Tonkinese permitted members of the royal family to live unmolested, ‘provided they made no disturbance.’

Unlike Fai-fo, Hué was gratifyingly busy. Abreast of the town there were twenty-five Chinese junks at anchor. Innumerable country boats were passing and repassing, and the shore was thronged with people. Its viceroy, who received Chapman from the comfort of his hammock, was a delight:

He was a venerable old man about sixty years of age, with a thin silver beard, of most engaging manners. His dress was plain and simple like the rest of the Tonquineese, consisting of a loose gown of black glazed linen with large sleeves, a black silk cap on his head stiffened into a particular form, and sandals on his feet. The cordiality which he received us with … still inclines me to acquit him of being voluntarily the author of the unmerited ill treatment we afterwards experienced. He himself and others often hinted to me that although the first in rank, he was subject to the control of his colleagues.

‘Pleasure seemed to dance in the old gentleman’s eyes at the few little compliments I made him,’ says Chapman. For his part, the viceroy declared that the English displayed better manners than any other Europeans he had encountered; this despite the unaffected relish with which one of the tars enjoyed the brandy served at dinner. The Jenny was spared anchorage fees and other duties, and the viceroy indicated that he would purchase some of her goods for himself. The remainder, he said, might be sold as Chapman wished, and if any officials proved obstructive, he was given sanction to throw them in the river.

Greatly satisfied with this reception, Chapman next paid his respects to Quan Tam Quon, the eunuch commander-in-chief of Hué’s galleys and army. Here was a study in contrasts:

We seated ourselves upon some chairs placed for us before a rattan screen from behind which a shrill voice called our attention to the object of our visit. He did not however become visible till the common questions were passed and I had acquainted him with my reasons for coming to Cochin China. The screen was then turned up and a glimmering light diffused from a small waxen taper, disclosed to our view, not the delicate form of a woman the sound had conveyed the idea of, but that of a monster disgustful and horrible to behold … Great flaps hung down from his cheeks like the dewlaps of an ox, and his little twinkling eyes were scarcely to be discerned for the fat folds which formed deep recesses around them.

Warned by his landlord that the favour of this ‘devil incarnate’ was only to be purchased by ‘sacrificing to his avarice,’ Chapman gifted him a gold repeating watch set with diamonds and emeralds. He says it was received with indifference, ‘notwithstanding it was chosen by his own jackal.’

A month was spent exchanging civilities and fixing bargains. Since it coincided with the autumn rains, against which Chapman’s quarters were scarcely proof, he moved into alternative accommodation. This produced an unexpected reaction in his host:

… a young man … came and complained to me that he had been cruelly beaten by Ong-ta-hia for being instrumental in my leaving his house … The following day I was alarmed by the same person running to me and conjuring me to hasten to Ong-ta-hia if I wished to save two of my people he was just going to put to death … We found his house filled with a great number of Chinese, some of whom were busy in binding a poor sick Frenchman and a cook belonging to Captain Hutton to the pillars of the house. Ong-ta-hia had a drawn sword in his hand and foamed at the mouth like a madman.

I desired to know the reason for his behaving so, but he was too much agitated to acquaint me, and retired. I then applied to some of the Chinese. They told me that the Frenchman had some trifling dispute with a woman in the bazar that sold eggs, who had made a complaint to Ong-ta-hia, and, they believed, his having taken a rather larger dose of opium than usual, was the cause of his behaving in this outrageous manner.

Ordered to pay for the goods he had purchased from Captain Hutton, or forfeit his house, Ong-ta-hia climbed onto its roof and prised off its tiles, with which to pelt passers-by. At last, overcome by the noise of the copper basins, drums, trumpets and bells of the exorcists engaged to expel his evil spirit, he collapsed into a stupor. The money was not paid.