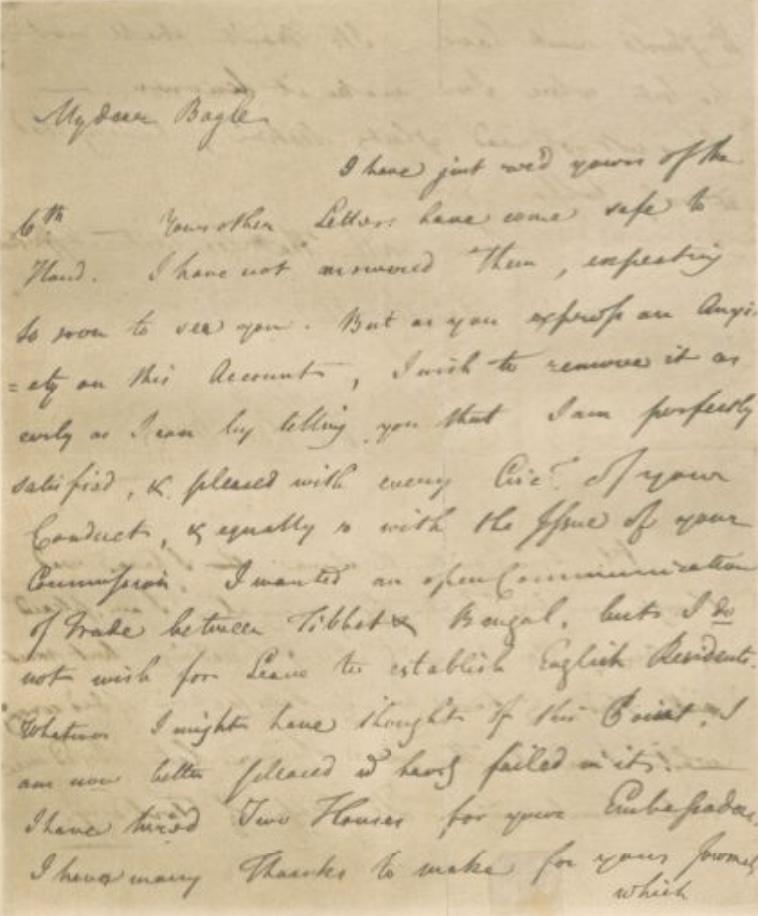

The Panchen Lama’s Letter

The events which gave rise to the Lama’s letter originated in a conflict between Bhutan and the north Indian state of Cooch Behar. Bhutan’s involvement there dated from 1661, when its ruler, Pran Narayan, was driven out by the Mughal Aurangzeb. The Bhutanese gave him refuge and thereafter involved themselves in infighting between the kingdom’s factions. After 1763, they controlled much of its territory, and directed affairs through a tribute-paying puppet. In 1772, their third appointee, Rajendra, died and the native opposition crowned Dharendra, the son of the previous king. The Bhutanese were pushed back into the hills before, with a force of some eighteen thousand, they returned. The capital was overrun and a new puppet, Bijendra, was installed. Like Rajendra, he was supervised at the frontier post at Chitakota (‘Chichakotta’) and, like him, he quickly succumbed to the malaria of the foothills. The Bhutanese took complete control, and Dharendra fled to Rangpur, where he appealed to the Company for aid.

Hastings, concerned at the instability on his frontier, was sympathetic. In April 1773, a treaty was agreed. Cooch Behar was annexed to Bengal, and half of its revenues were ceded to it. Troops were then sent and, at a cost which caused the Company some embarrassment, the Bhutanese and their lowland allies were driven back.[5]

In early 1774, after an expensive defeat at Chitakota, Desi Zhidar (‘Deb Judhur’), Bhutan’s secular ruler, was deposed His disregard for its spiritual leader, Jigme Sengay, had made him unpopular. So had his habit of cultivating Tibetan, and indirectly, Chinese support. He was replaced by Kuenga Rinchen, a former ally, whose hopes of appointment as Je Khenpo (Chief Abbot) he had disappointed. (It was said that, anticipating disaster, Kuenga Rinchen used false auguries to persuade Zhidar to lead his troops against the British.)[6]

Zhidar fled to Lhasa, whose regent he asked to mediate with Bhutan. For a time, he advocated putting Zhidar in charge of Bhutan’s province of Paro. In the end, however, Zhidar was placed under house arrest at Gyantse, on the not unreasonable grounds that he would cause trouble, or that he might involve his allies, the Gurkhas, in his quarrel. (To confound Zhidar’s sympathisers, Kuenga Rinchen let it be known that he had been murdered on his way to Tibet; probably, he was executed in 1776.) It was partly at Gurkha instigation that the Panchen Lama sent his delegation, comprising a Tibetan, Paima, and a Hindu pilgrim, Purangir Gosein, to Hastings.[7]

[He wrote] I have been repeatedly informed that you have been engaged in hostilities against the Deb Judhur, to which, it is said, the Deb’s own criminal conduct, in committing ravages and other outrages on your frontiers, has given rise … He is of a crude and ignorant race … However, his party has been defeated … and he has met with the punishment he deserved … I now take upon me to be his mediator, and to represent to you that, as the said Deb Rajah is dependent upon the Dalai Lama, who rules in this country with unlimited sway (but on account of his being in his minority, the charge of the government and administration for the present is committed to me) should you persist in offering further molestation to the Deb’s country, it will irritate both the Lama and all his subjects against you. Therefore, from a regard to our religion and customs, I request you will cease all hostilities against him, and in doing this you will confer the greatest favour and friendship upon me.

Whether this letter meant to infer that the desi alone was dependent on the Dalai Lama, or Bhutan as a whole, is perhaps open to debate. (The Bhutanese would have protested their independence, had they known of the Lama’s intervention; the British took time to appreciate that Bhutan and Tibet were separate.) A treaty with Kuenga Rinchen was agreed, on 25 April 1774. Since this rendered the country accessible, Hastings proposed sending George Bogle to Lhasa, to capitalise on the Panchen Lama’s goodwill and to negotiate a treaty of amity and commerce. Alexander Hamilton, assistant surgeon in Calcutta, accompanied him.[8]

Bogle was one of Hastings’ Scots protégés, the ninth child in a family of Glasgow tobacco merchants. He was twenty-seven. In 1772, the family’s fortunes had been ‘blasted’ in the crash caused by the speculator Alexander Fordyce. They looked to George to aid their revival. By attaching himself to Hastings, Bogle rose quickly through the ranks, to Secretary to the Calcutta Select Committee. This made him familiar with developments at the frontier. He was trustworthy, fond of travelling, and had indicated that respite from office work would be welcome. He was a natural choice for the mission.[9]

Bogle in Bhutan (May – October 1774)

Bogle’s instructions came in two parts. First, to ‘open a mutual and equal communication of trade between the inhabitants of Bhutan and Bengal.’ Second, to explore the traffic between Lhasa and its neighbours. Looking back, Hastings’ kinsman, Samuel Turner, explicitly referred to China. He wrote,

The contiguity of Tibet to the western frontier of China … suggested, also, a possibility of establishing, by degrees, an immediate intercourse with that empire, through the intervention of a person so revered as the Lama, and by a route not obviously liable to the same suspicions, as those which the Chinese policy had armed itself against all the consequences of a foreign access by sea.[10]

Unfortunately, expectations for the Lama’s influence stemmed from a misapprehension. His envoys had exaggerated his political standing with the emperor. He had religious authority, but his monastery was at Tashilhunpo, near Shigatse. The seat of the senior, but infant, Dalai Lama was at Lhasa. There, he was supervised by an unpopular Chinese regent and two ambans. The Panchen Lama may have initiated Tibet’s effort at diplomacy, but he could not conclude it without reference to its capital and, ultimately, to Peking.[11]

Alongside his formal instructions, Bogle was given a private list of tasks which resonate with the enlightened temper of the times, and of Warren Hastings. In particular, to keep notes on the characteristics of the people he encountered: ‘their manners, customs, buildings, cookery &c.’ Hastings was delighted with the result, the tone of which reflects well on Bogle’s character. He encouraged him to prepare it for publication. In 1876, it finally appeared.[12]

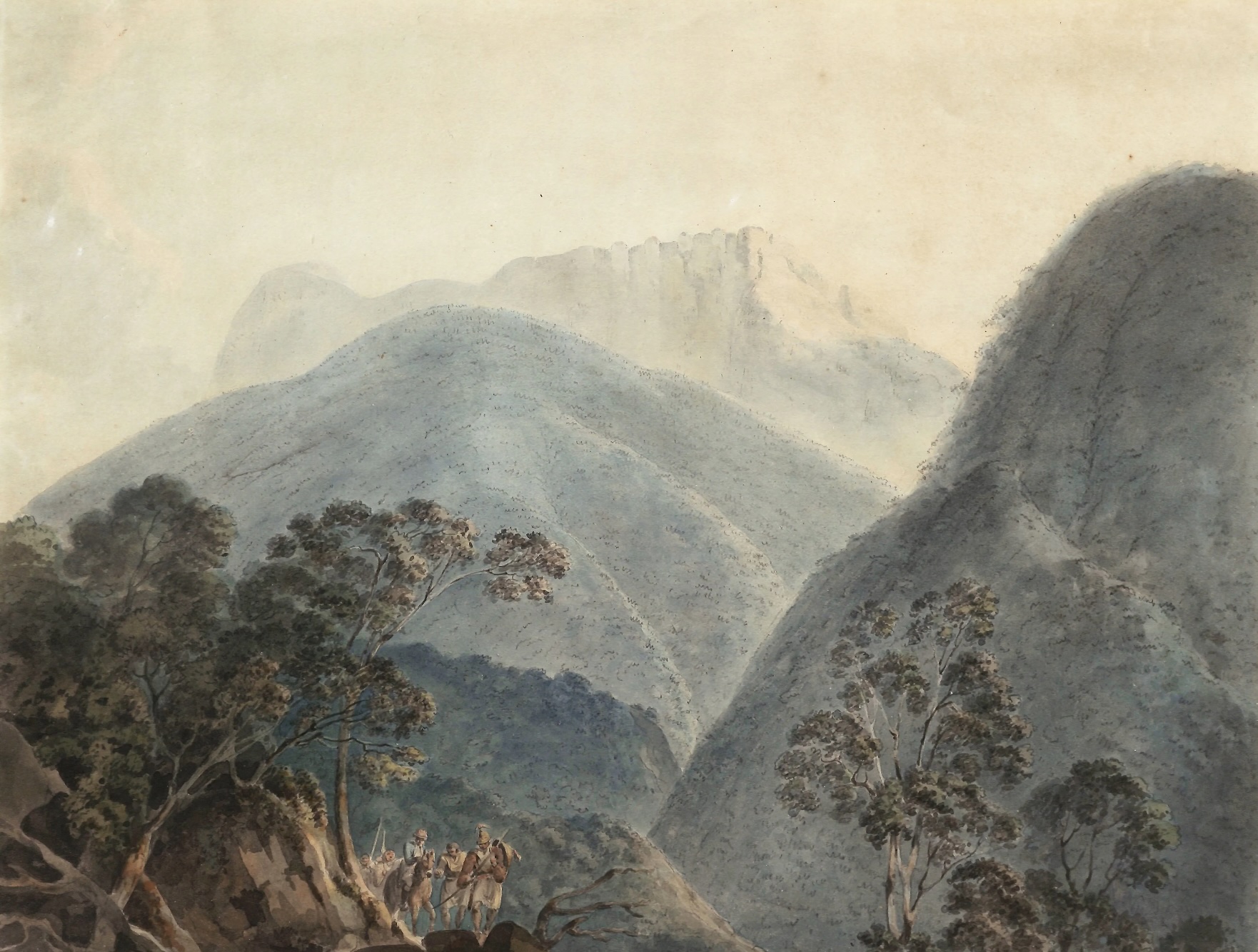

Bogle and Hamilton left Calcutta, in May 1774. They travelled via Murshidabad and Rangpur before reaching a lowland scrub of ‘long grass … frogs, watery insects, and dank air’ near the border. Their first night in Bhutan was spent in a house with the look of a birdcage which, for a stair, sat atop a notched tree stump. That evening, with the village headman, his neighbours, and a female pedlar with ‘Rubens’ wife’s eyes’, they got ‘tipsy with a bottle of rum.’ The next morning, they followed the route to Buxa Duar, one of eighteen ‘doors’ through the mountains. At its top stood an outpost which, during the campaign against Zhidar, had been reduced to ‘a 3-feet wall of loose stones … a fine old banian tree; that’s all.’ Even so, the British were kindly received by its commander, fed with butter, rice, milk and tea, and issued with the necessary pass.

Bogle remarked on how difficult the terrain must have been for the Company’s troops. It became tougher. Two squat ‘tangun’ ponies belied appearances and proved surprisingly sure-footed on the stones of ‘bastard marble’ which served as the trail. Otherwise, goods were transported by coolie:

[He writes] This is a service so well established that the people submit to it without murmuring. Neither sex, nor youth, nor age exempt them from it … Naturally strong, and accustomed to this kind of labour, it is astonishing what loads they will carry. A girl of eighteen travelled one day 15 or 18 miles, with a burden of 70 or 75 pounds weight. We could hardly do it without any weight at all.

From ‘Mount Pichakonum’, its peak crowned with holy flags, Bogle gazed back over the escarpment to the Bengal plain and contemplated the extraordinary abruptness of the change in terrain:

… What fine, baseless fabrics might not a cosmographer build on this situation, who, from a peat or an oyster-shell, can determine the different changes which volcanoes, inundations, and earthquakes have produced on the face of this globe. He would discover that the sea must once have covered Bengal, and washed the bottom of these mountains, which were placed as a barrier against its encroachments.

Following these ‘antediluvian reveries,’ he then considered how the mountain barrier had affected the people around him. The ‘thin-skinned’ bearers in his train, still recovering from the climb, were contrasted with the novel people of the mountains:

[The Bengalis’] country is cut through with rivers and creeks to carry their goods for them. The earth produces its fruits with an ease almost spontaneous, and every puddle is full of fish. The Bhutanese, of a constitution more robust and hardy, inhabit a country where strength is required. They have everything to transport on their backs; they are obliged to make terraces, and conduct little streams of water into them, in order to cover their rice fields, and to build houses with thick stone walls, to secure themselves from the cold. The one cannot endure heat, the other cannot suffer cold; and so these mountains are set up as a screen between them.[13]

There is a sign here of weariness with the people of the plain, and of excitement at the prospect of new encounters. Bogle’s sympathy with the unfamiliar cultures of the mountains grew with time.

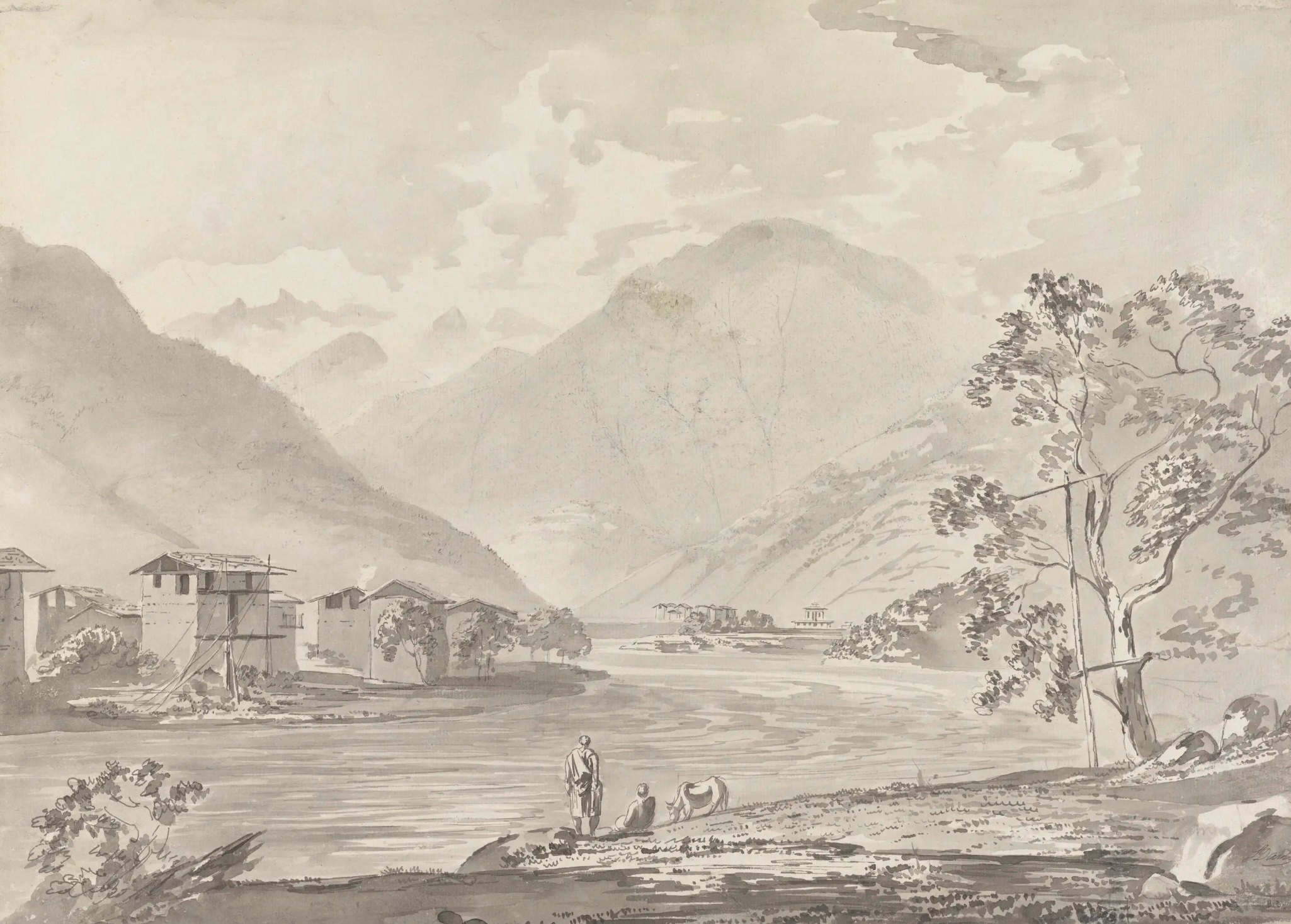

After the village of Jaigugu, where Bogle planted some potatoes given to him by Hastings, the trail followed the Wang Chhu (‘Pachu-Chinchu’) river towards Thimpu (‘Tassisudon’). Frustratingly, the Bhutanese had not used its course to fashion a more level road, a failing which Bogle thought deliberate, to make the country more difficult of access. Despite this, and the defection of the cook (‘an uxorious man … his wife enticed him away’), he found the journey a revelation, notwithstanding the ‘perpetual Ascending and Descending.’ Nurturing a moustache in the Bhutanese style, he wrote to his sister, declaring it ‘cut a very respectable figure’ when ‘sleeked down with pomatum.’[14]

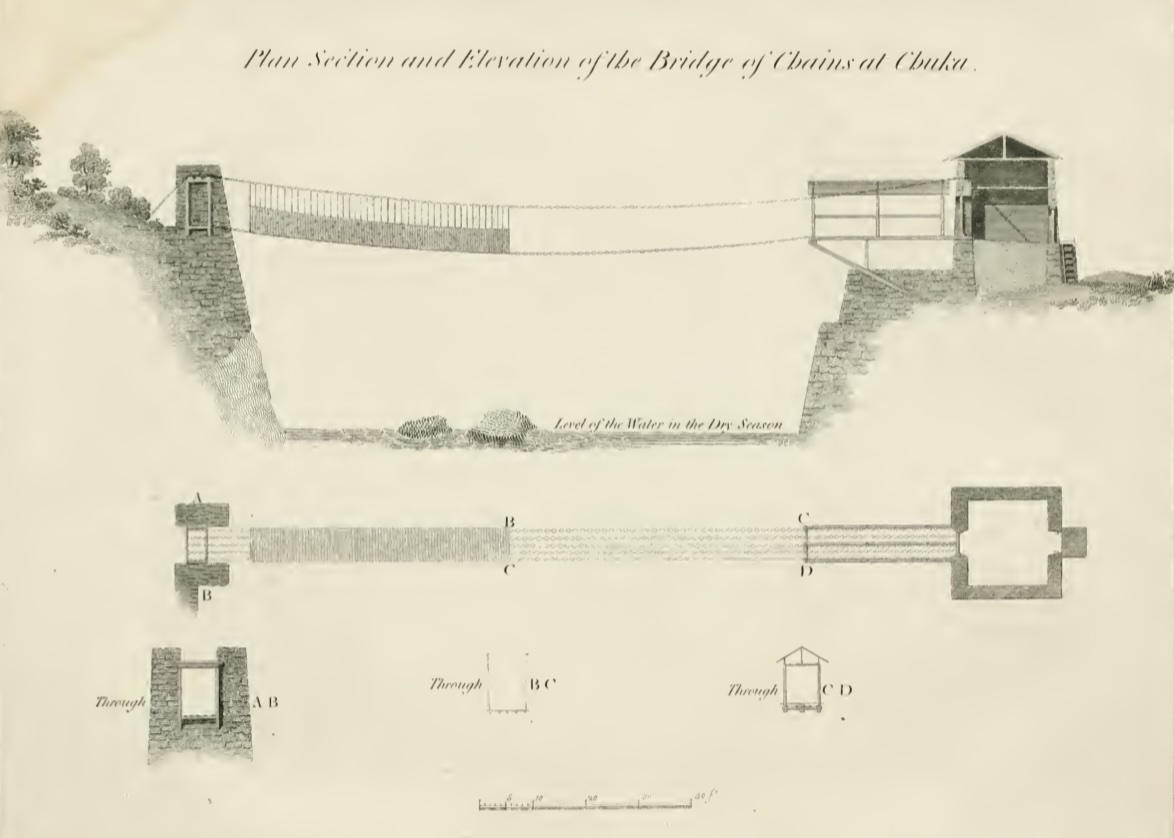

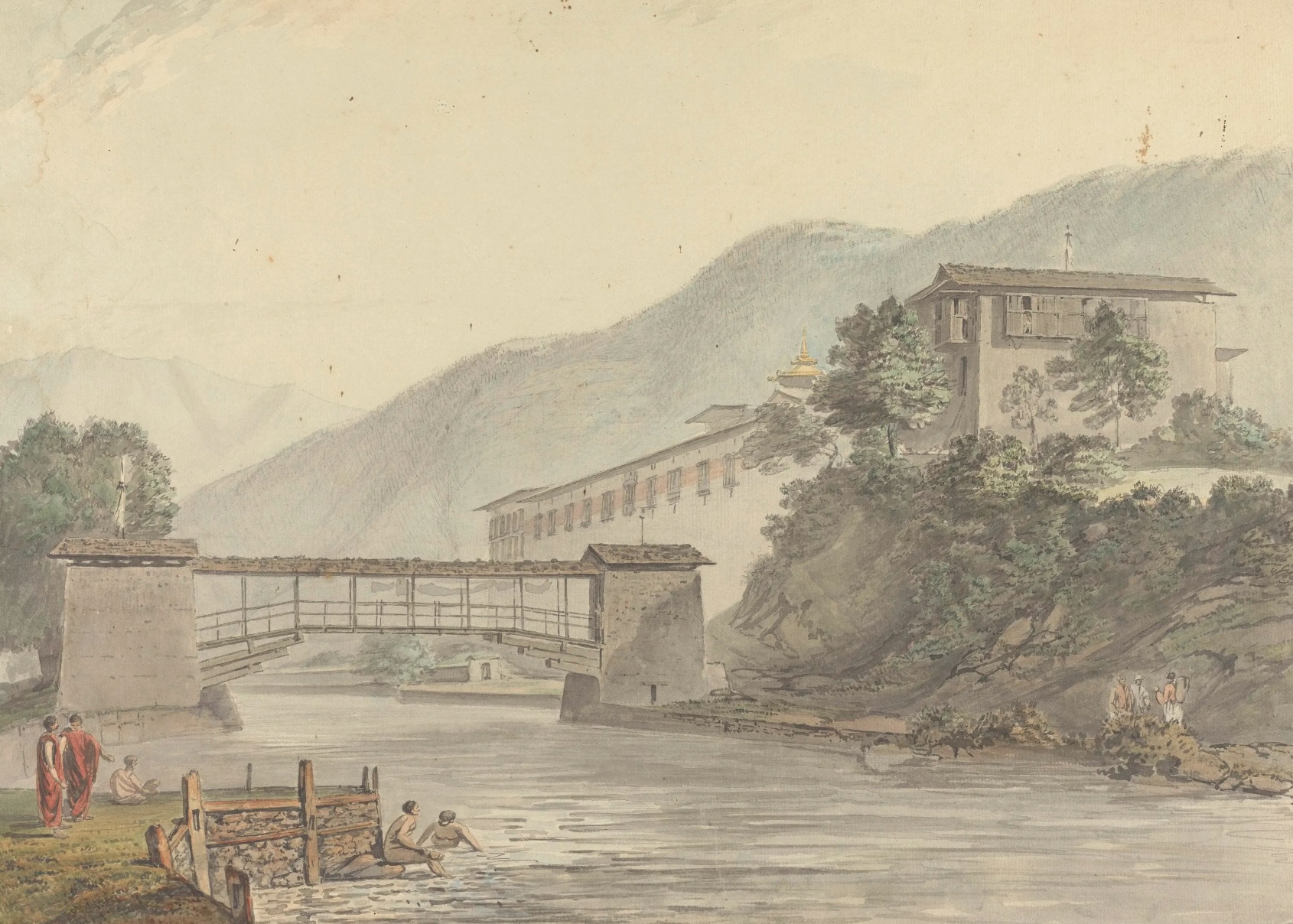

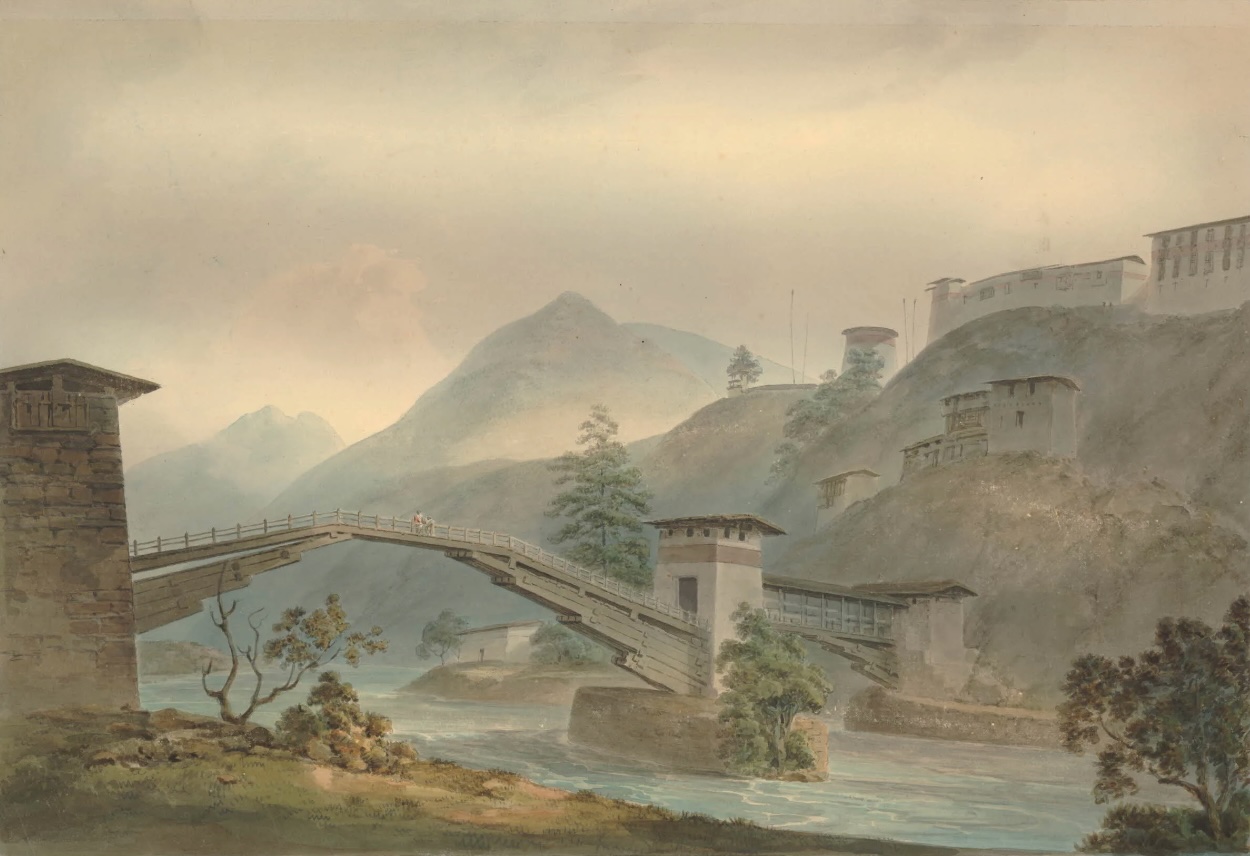

One long day’s journey after Muri-jong, he climbed around a rock overhanging the river on a set of almost perpendicular steps, and passing through a passage cut into its top, obtained a first sight of the iron bridge at Chukha. This was one of several constructed, in the fifteenth century, by Thangtong Gyalpo, to make pilgrimage easier. Chakzampa (‘Iron Bridge Man’), was reputed to have lived to one hundred or more: his reputation for repelling invaders told against public admission of an earlier death. Of the bridge, Bogle makes slight mention but, in 1783, Samuel Turner was greatly impressed. His published account includes a sectional drawing of the structure, which he compared to a bridge across the Tees. He declared that the works of its creator, including the road to Chukha, many parts of which were connected to the precipice with iron pins and clamps, ‘do credit to a genius, who deservedly ranks high upon the rolls of fame.’[15]

After Chukha, the country became flatter, allowing for arable crops, a greater population, and an easier trail. Then, as the party approached Thimpu, there appeared a messenger from the Panchen Lama. He brought disconcerting tidings:

Having heard of my arrival at Kuch Bahar on my way to him, and, after some formal expressions of satisfaction, [he] informs me that his country being subject to the Emperor of China, whose order it is that he shall admit no Moghul, Hindustani, Patan, or Fringy, he is without remedy, and China being at the distance of a year’s journey prevents his writing to the Emperor for permission; desires me therefore to return to Calcutta.

Happily, a letter for Purangir spoke of a delay only, and gave as an explanation the occurrence of smallpox, which had obliged the lama to retreat northwards. Deliberately, Bogle prevaricated. He was rewarded with permission to meet the desi, at Thimpu.[16]

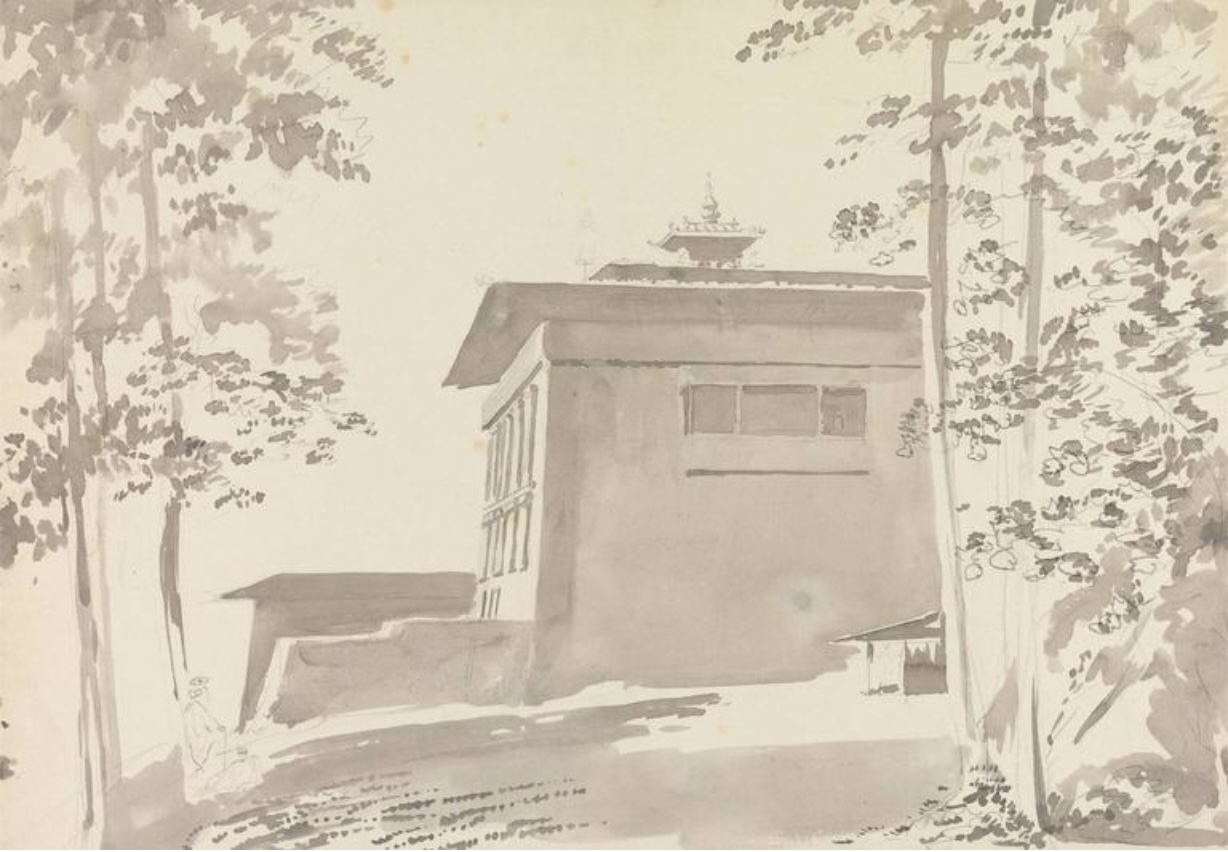

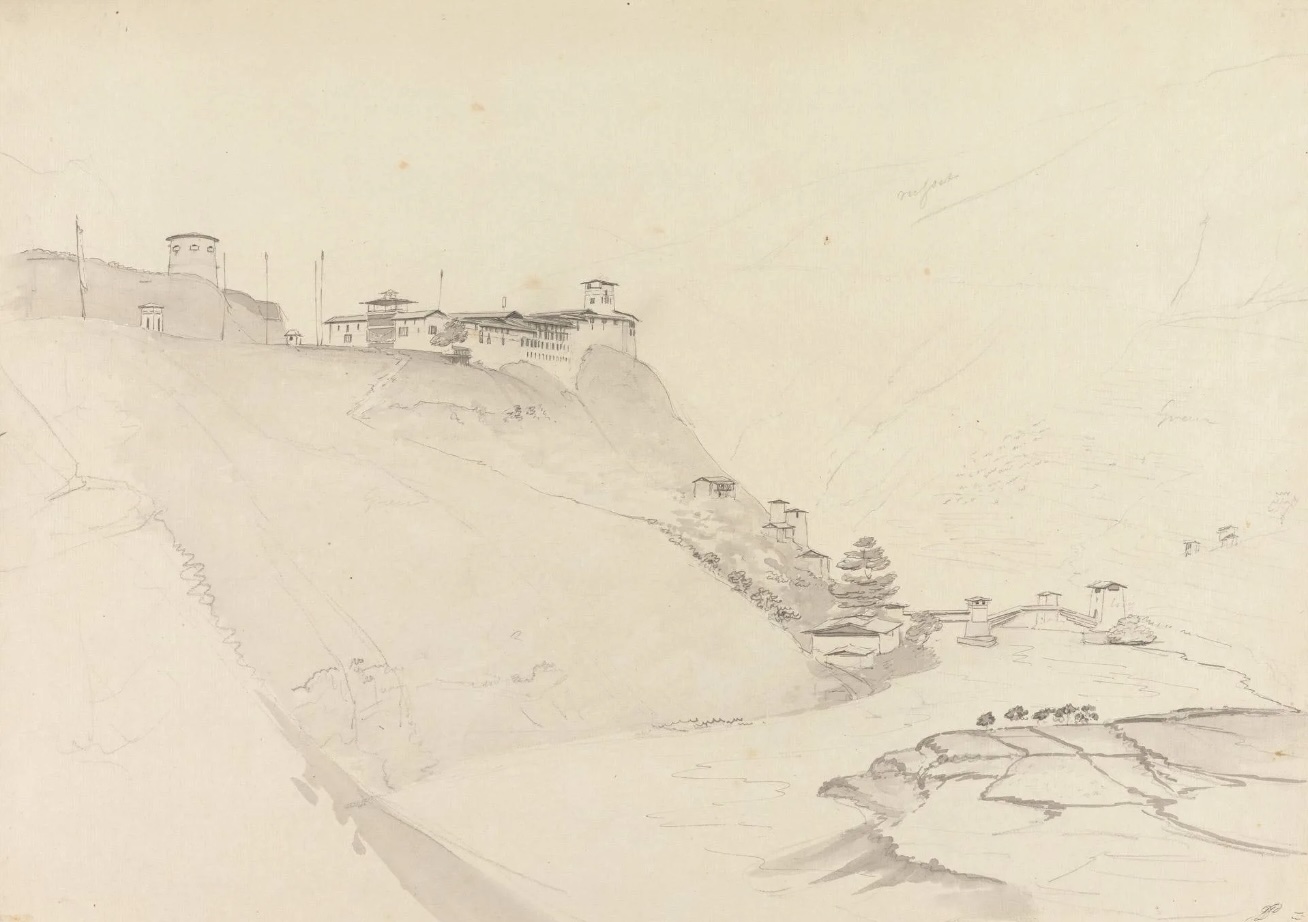

Two days after Kuenga Rinchen’s entry into the city, which Bogle describes, he was summoned to the dzong. When he received him, the desi was seated on a throne two feet from the floor. He wore a priestly habit of scarlet cotton and a gilded ‘mitre’. Officers were seated on cushions close to the wall, and one twirled a small white umbrella over him. In a letter to his sister, Bogle described Bhutan’s secular ruler as ‘a pleasant looking old man; with a smirking Countenance.’ He made his bows and presented his gifts, and was offered some refreshments:

In came a man carrying a large silver kettle, with tea made with butter and spices, and having poured a little into his hand and drank it, he filled the Deb Rajah a cup, then went round to all the ministers who, as well as every other Bhutanese, are always provided with a little wooden cup, black glazed in the inside, wrapped in a bit of cloth, and lodged within their tunic, opposite to their heart and next their skin, which keeps it warm and comfortable; and last of all the cup-bearer filled my dish. The Rajah then said a grace, in which he was joined by all the company.

When we had finished our tea, and every man had well licked his cup, and deposited it in his bosom, a water tabby gown, like what Aunt Kitty used to wear, with well-plated haunches, was brought and put on me; a red satin handkerchief was tied round me for a girdle. I was conducted to the throne, where the Deb Rajah bound my temples with another satin handkerchief, and squeezing them hard betwixt his hands, muttered some prayers over me, after which I was led back to my cushion. We next had a cup of whisky fresh and hot out of the still, which was served round in the same manner as the tea, of which we had also two more dishes, and as many graces; and last of all betel nut.[17]

Kuenga Rinchen’s position was delicate. He was reluctant to plead Bogle’s case to the Panchen Lama, as it might imply Tibetan suzerainty over Bhutan. Tibet was ruled by Gelugpa Buddhists, Bhutan by Drukpas. The ancestors of its leading families had quit Tibet as refugees and had beaten off several attempted invasions. So, whilst the lama was the desi’s religious superior, their governments were ‘distinct.’ Additionally, the size of Bogle’s escort, a cavalcade brought out of consideration for the Company’s honour, made the desi nervous. The recent war had made a distinct impression, just as Kinloch’s expedition had impressed the Gurkha Raja. Of greatest import, however, was the attitude of China. Zhidar had cultivated the protection of its emperor by circulating his seal in the country. It had since been suppressed, but Kuenga Rinchen had little appetite for provoking him by admitting feringhis.[18]

Ultimately, Bogle resolved the stalemate by sending Purangir to the Panchen Lama. The smallpox necessitated a round-about route, which took two full months. They passed slowly. Thimpu was ‘monkish to the greatest degree,’ the desi and his entourage being ‘immured like state prisoners’ in his immense palace. There were some distractions; the teschu dance festival, games of quoits (degor), even some pigeon-shooting (strangely, no one objected to Bogle’s bloodletting). Zhabdrung’s regent, Jigme Sengay (‘Lama Rimpoche’), provided much-needed companionship. In Zhidar’s day he had been unapproachable, but times had altered:

After the first visit he used to receive us without any ceremony, and appeared to have more curiosity than any man I have seen in the country. One day Mr. Hamilton was showing him a microscope, and went to catch a fly; the whole room was in confusion, and the Lama frightened out of his wits lest he should have killed it … He has got a little lap-dog and a mungoos, which he is very fond of.[19]

Regarding commerce, Bogle informed Hastings that the jealous eye with which he was viewed necessitated that he proceed cautiously. Were he to appear inquisitive, fresh obstacles might be put in the way of his journey. He established that the annual caravan to Rangpur was an adventure principally of the desi and a few senior figures. The wealth accruing to them made trade liberalisation problematic. The Panchen Lama, however, had ‘no such warp.’ He decided to concentrate on him. If he were won over, he might exert his influence on the desi. Otherwise, Bhutan’s unsettled state made negotiations difficult. Fears of a Lhasa-sponsored insurrection, supportive of Zhidar, opened requests for freedom of trade for Tibetans to suspicions of treachery.[20]

Bogle estimated the trade was worth just a third or a quarter of that which passed through Nepal; not enough, certainly, to justify military operations beyond Cooch Behar. Anyway, following the 1774 treaty, the Bhutanese were peaceful. Bogle added, optimistically,

The simplicity of their manners, their slight intercourse with strangers, and a strong sense of religion, preserve the Bhutanese from many vices to which more polished nations are addicted. They are strangers to falsehood and ingratitude. Theft, and every other species of dishonesty to which the lust of money gives birth are little known.[21]

On 18 September, it was announced that, following the Panchen Lama’s intercession, Lhasa had consented to Bogle’s continuing his journey, with a small party. There was a brief delay while some supporters of Zhidar attempted to capture the capital: they retreated to Simtokha whence, after a ten-day siege, they fled to Tibet. Then, on 13 October, Bogle left Thimpu with Hamilton, Mirza Settar, a Kashmiri merchant, and Paima, who had been sent from Tashilhunpo to collect him.[22]

Bogle in Tibet (October 1774 – May 1775)

A heavy shower of snow had fallen two days before. It much surprised the Bengali bearers, who were told ‘it was white cloths, which God Almighty had sent down to cover the mountains and keep them warm.’ This appealed to Bogle. So did the equanimity with which the women at Essana managed the heavy burden placed upon them:

Not unfrequently one sees them with a child at the breast, staggering up a hill with a heavy load, or knocking corn, a labour scarcely less arduous … But they seem to bear it all without murmuring; and, having nothing else to deck themselves with, they plait their hair with garlands of leaves or twigs of trees. The resources of a light heart and a sound constitution are infinite.

All was not tranquil. In Paro, Bogle was awoken by the firing of guns and a ‘war whoop’. He feared the insurgents had caught up with him, but the cause was the parading of a rebel’s head, which was being carried in a procession into the dzong.

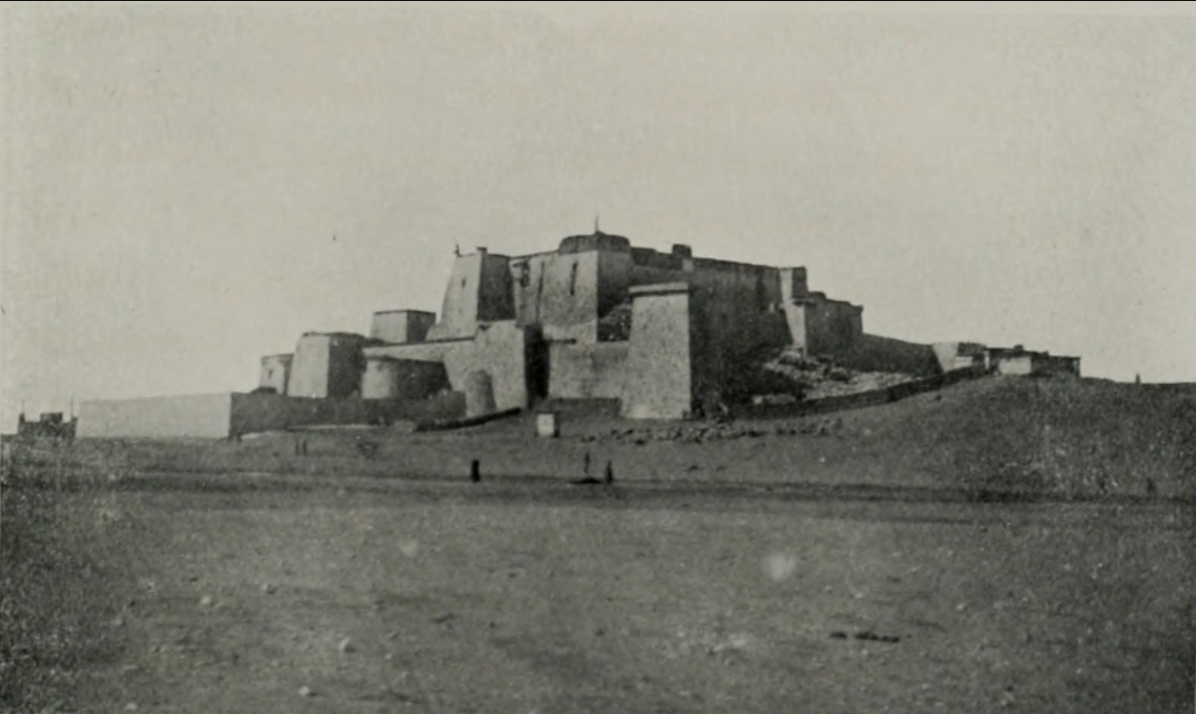

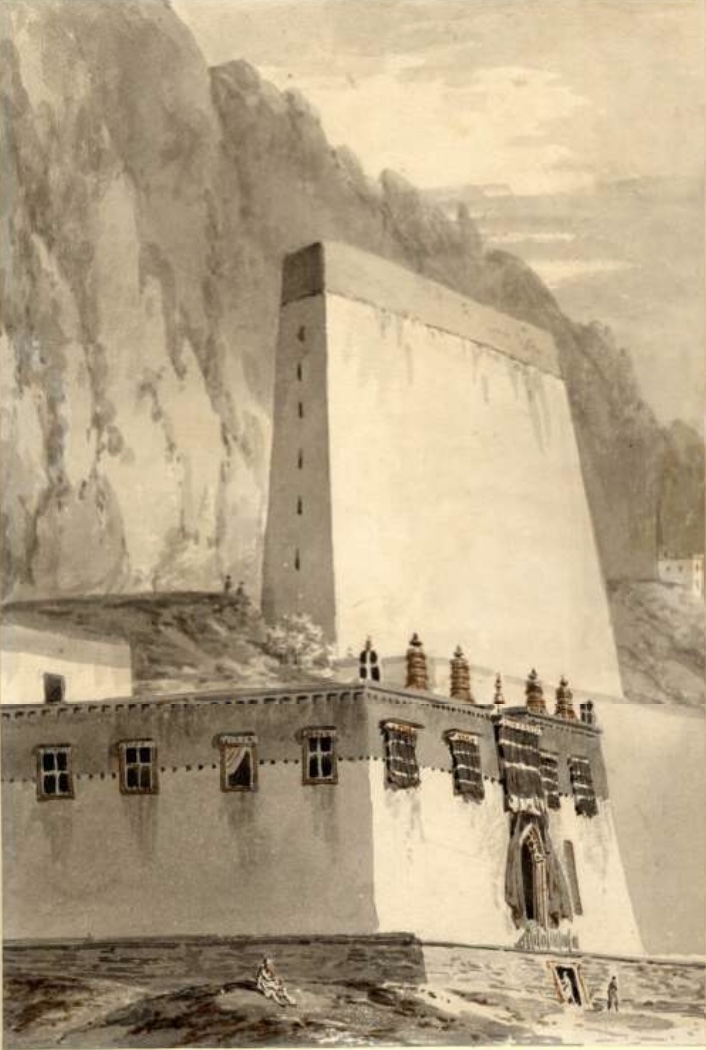

Now began the ascent to the Tibetan plain. On the approaches to the Tremo pass, there was a change in scene. Whereas, along the Paro Chhu, the trees had advertised the colours of autumn, now they were shorn of their leaves. It was noticeably colder and, since the first night was spent in an open barn, it was well to have brought a supply of fuel. The following day, as they descended into Phari, the party observed eagles and ravens circling over grounds where the citizens had exposed their dead. From a distance, Phari’s fortress impressed but, beneath it, the town underwhelmed. Bogle comments,

[The fort] rises into several towers with the balconies, and having few windows, has the look of strength; it is surrounded by the town. The houses are of two low stories, flat-roofed, covered with bundles of straw, and so huddled together that one may chance to overlook them … [The architecture] has a mean look after the lofty buildings of the Deb Rajah’s country; but having neither wood nor arches, how can they help it?

By comparison with others, this portrait flatters. To Edward Candler, who visited in 1903-1904, the filth was ‘indescribable’:

For warmth’s sake most of the rooms are underground, and in these subterranean dens Tibetans, black as coal-heavers, huddle together with yaks and mules … My last impression of the place as I passed out of its narrow alleys was a very dirty old man, seated on a heap of yak-dung over a gutter. He was turning his prayer wheel, and muttering the sacred formula that was to release him from all rebirth in this suffering world. The wish seemed natural enough.

Spencer Chapman visited Phari in 1936-1937. He described it as an ‘excrescence’ on a dun plateau. The streets were so choked with garbage that they had risen many feet and, in most cases, obscured the ground-floor windows. Of this Bogle makes no mention, although he writes that Phari was exposed to a ‘ruffian’ wind and that the ferocity of the dogs made it wise to keep indoors at night.[23]

On the other hand, while others have declared that Mount Chomolhari compensates for Phari’s failings, Bogle barely acknowledges it. Instead, his attention was drawn to a crowd of followers who were gathering around Paima:

One of Paima’s servants carried a branch of a tree with a white handkerchief attached to it. Imagining it to be a mark of respect to me and my embassy, I set myself upright in my saddle; but I was soon undeceived, for … we rode over the plain till we came to a heap of stones opposite to a high rock covered with snow. Here we halted, and the servants gathering together a parcel of dried cow-dung, one of them struck fire with his tinderbox, and lighted it … When the fire was well-kindled, Paima took out a book of prayers; one brought a copper cup, another filled it with a kind of fermented liquor out of a new-killed sheep’s paunch, mixing it with some rice and flour, and after throwing some dried herbs and flour into the flame, they began their rites.[24]

To describe Chomolhari, which rises nine thousand feet above the plain to a height of twenty-four thousand feet, as ‘a high rock covered with snow’ really is an extraordinary understatement.

At close to fifteen thousand feet, the going was tough. At day’s end, the exhausted Hindu bearers were carried home by the Tibetans. (They might have used the yaks but they feared an accident, following which they would have had ‘to beg their bread during twelve years, as an expiation for the crime.’) As the motley procession stumbled along the broadening valleys past the Sham Chu (Duoqingcuo) and Calo Chu (Galacuo) lakes, it was beginning to dawn on Bogle that Tibet’s inhabitants were ‘of a distinct race from those in the Deb Rajah’s country.’ Less robust, he judged them, but more civilised:

Goods are chiefly carried on by bullocks and asses; the corn is trod out by cattle, and ground by water-mills, and the country producing no forests, the inhabitants are freed from the hard labour of hewing down trees … This renders the Tibetans much better bred and more affable than their southern neighbours, and the women are treated with greater attention. In the Deb Rajah’s country, whatever a countryman saves from his labour is laid out in adorning his sword with silver filigree work … Here it is bestowed on purchasing coral and amber beads, to adorn the head of his wife.[25]

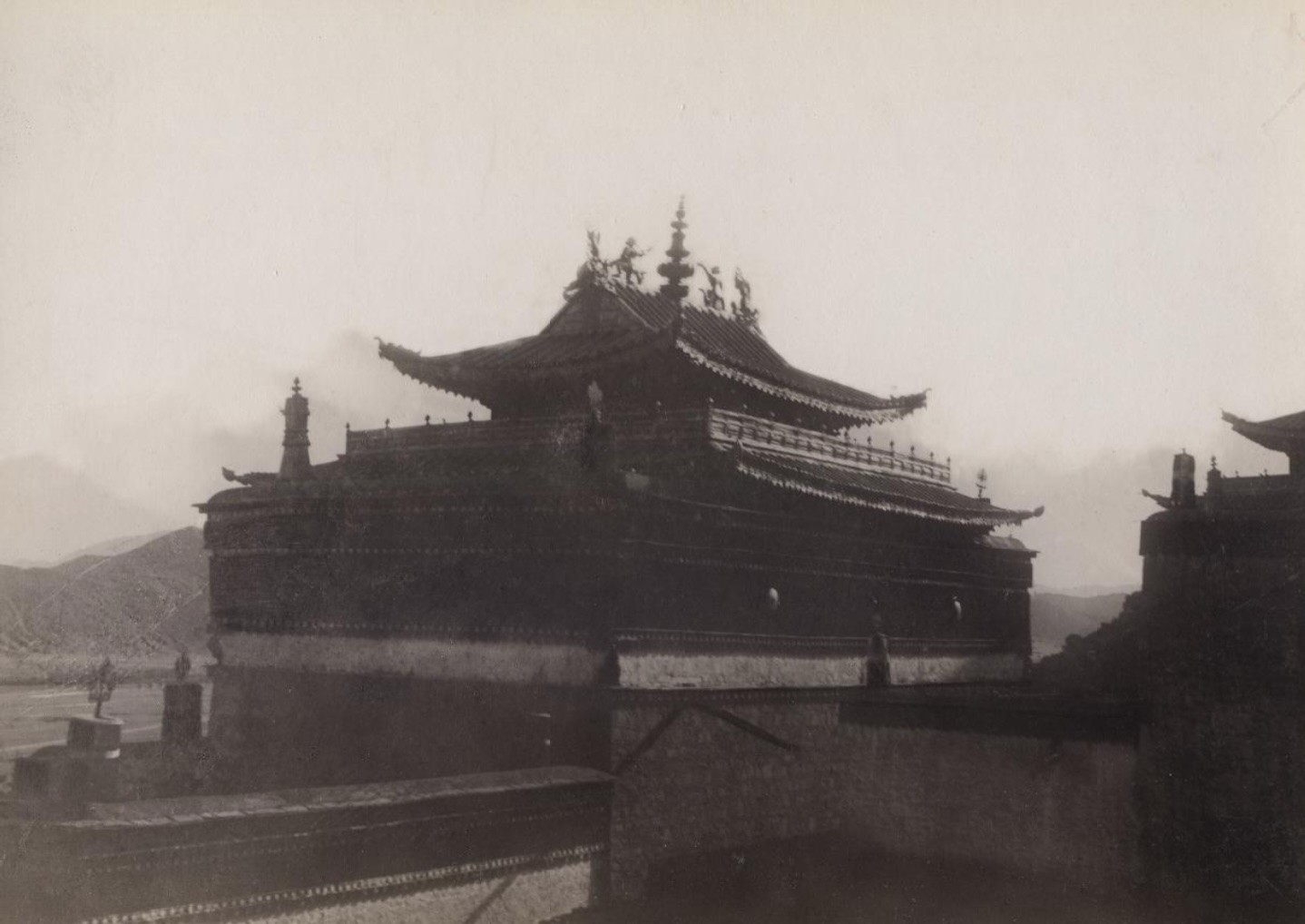

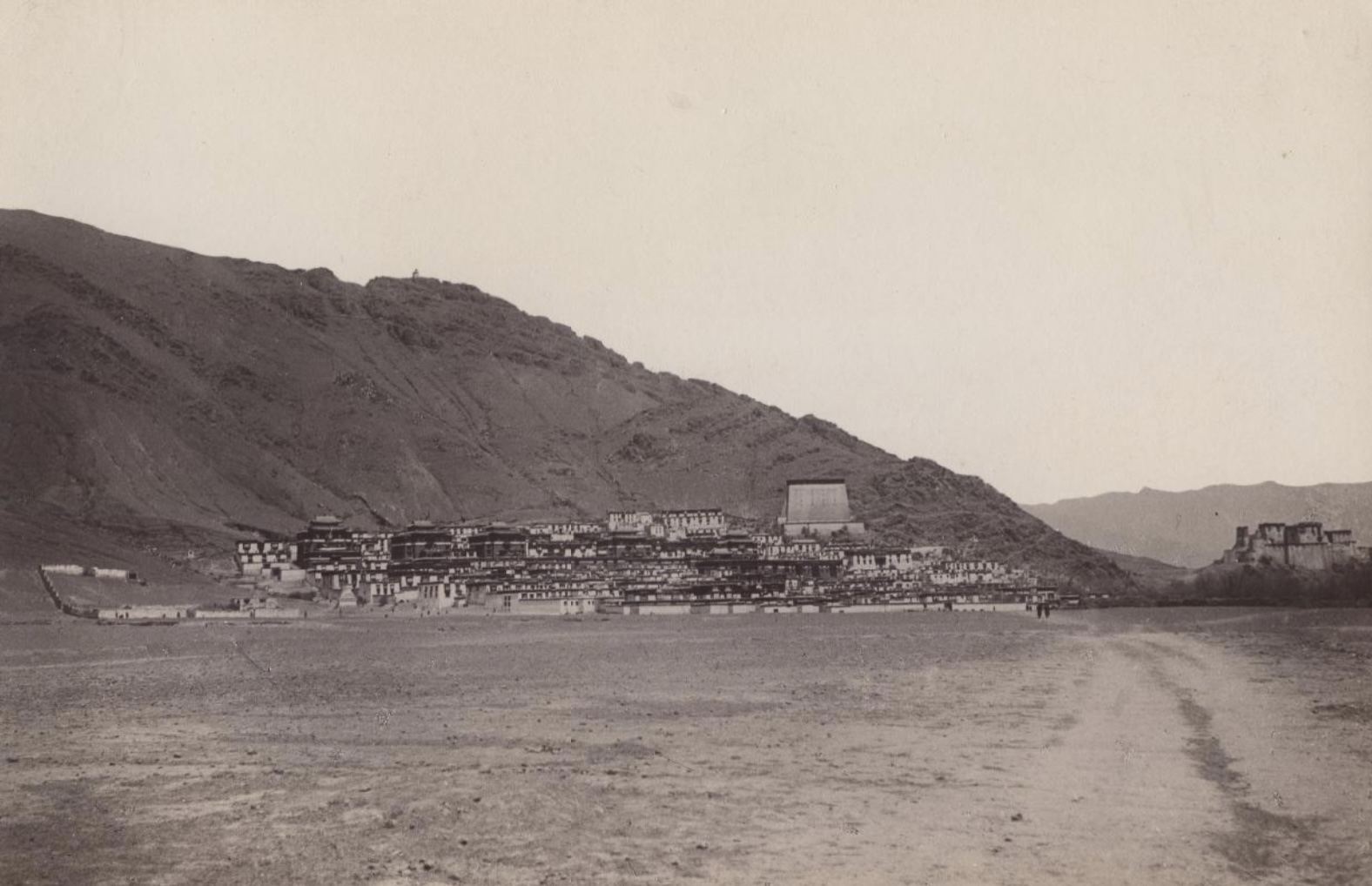

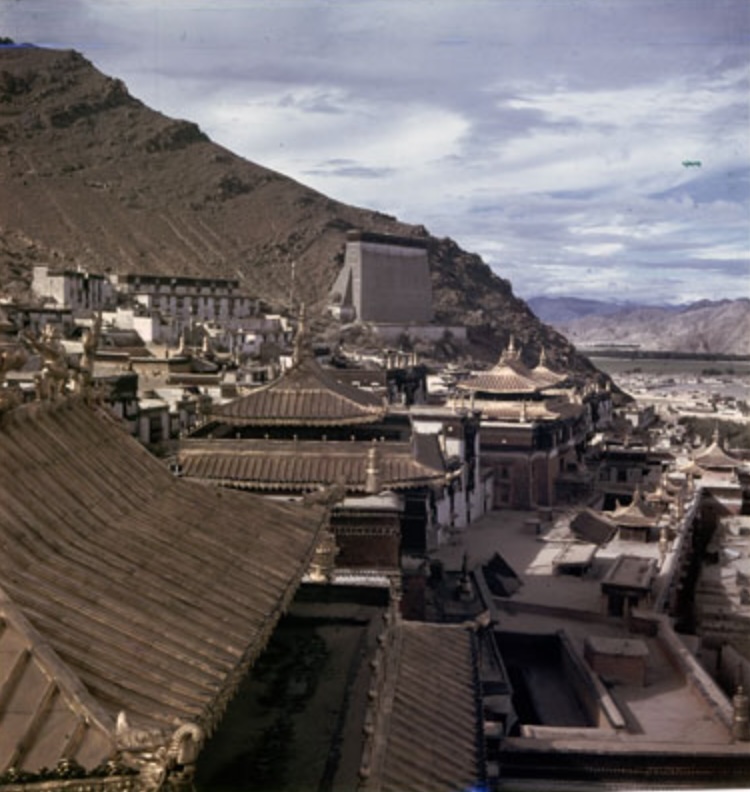

At Gyantse, the party was joined by Purangir and, on 8 November 1774, they reached Dechenrubje (‘Desheripgay’). The Panchen Lama’s refuge was hidden in a narrow valley at the foot of an abrupt, rocky hill. It was small, just two storeys high. Broad ladders took the place of stairs; the roofs were decorated in copper and gilt. In front, there were three brass plates, representing ‘Om, Han, Hoong’, the invocations of the faithful.

The envoys were greeted by servants offering tea, rice, whisky, and three or four dried sheep carcasses, a curious speciality. Bogle writes,

They are as stiff as a poker, are set up on end, and make, to a stranger, a very droll appearance … The sheep is killed, is beheaded, is skinned, is cleaned; the four feet are then put together in such a manner as may keep the carcass most open. During a fortnight it is every night exposed on the top of the house, or in some other airy situation, and in the heat of the day it is kept in a cool room … The Tibetans often eat it raw, and I once followed their example; it had much the taste of dried fish.

He reasoned that the meat was preserved from putrefaction by the cold, ‘the uncommon dryness of a gravelly and sandy soil, and partly to the scarcity of flies and other maggot-breeding insects.’[26]

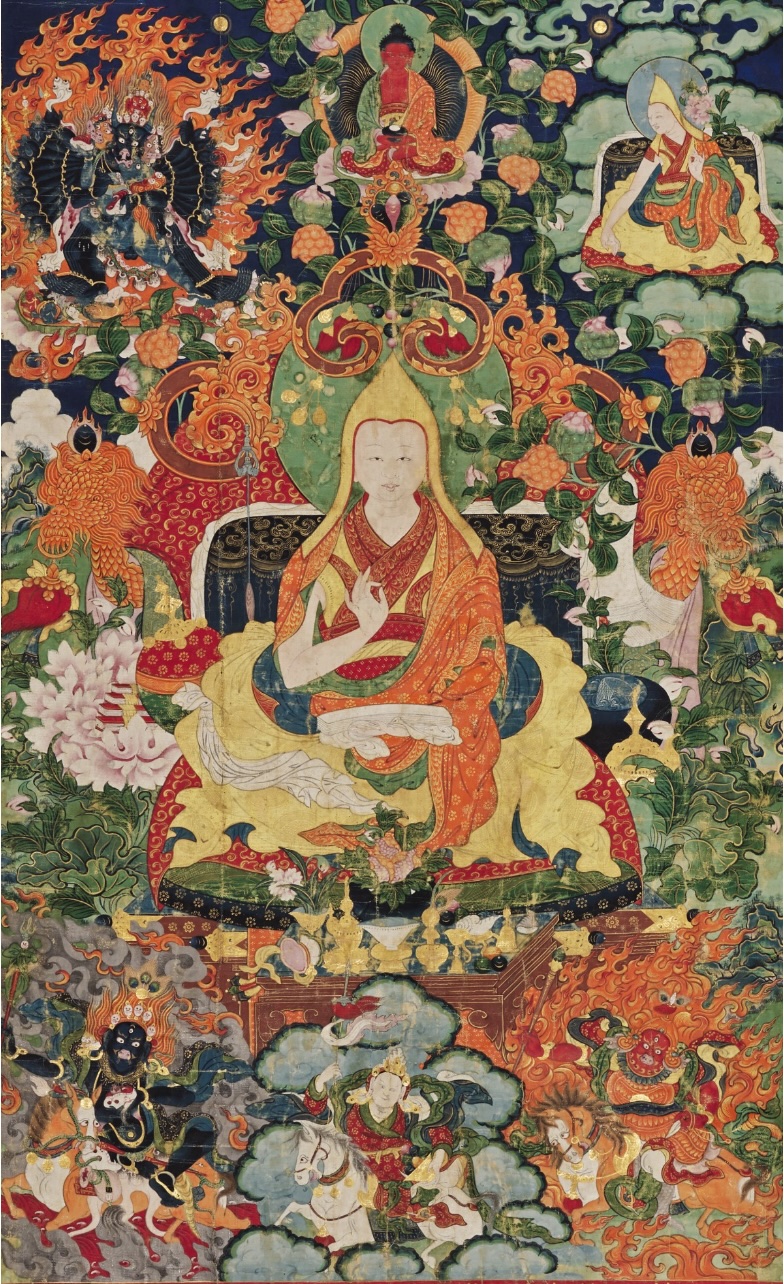

‘God’s vice-regent’ received Bogle that afternoon. He sat cross-legged on a gilded throne, wearing a yellow, sleeveless jacket and mantle, and a mitre-shaped cap. On one side, stood a physician holding sandal-wood rods for protection against disease, on the other, his ‘Sopon Chumbo’, or cupbearer.

Teshu Lama is about forty years of age, of low stature, and though not corpulent, rather inclining to be fat. His complexion is fairer than that of most of the Tibetans, and his arms are as white as those of a European; his hair, which is jet black, is cut very short; his beard and whiskers never above a month long … He is extremely merry and entertaining in conversation, and tells a pleasant story with a great deal of humour and action. I endeavoured to find out, in his character, those defects which are inseparable from humanity, but he is so universally beloved that I had no success, and not a man could find in his heart to speak ill of him.[27]

Bogle had feared the Panchen Lama’s inaccessibility would make diplomacy impossible, but his concern instantly evaporated. At subsequent meetings, the lama dispensed with his robes and most of his attendants. Bogle was given a purple satin tunic lined with fox fur, a yellow cap faced with sable, and a pair of red silk and hide boots. These provided protection against the cold and the curiosity of the Tibetans, who crowded about rather ‘as people go to look at the lions in the Tower.’

For a month they remained at Dechenrubje, while the lama received deputations of visitors. Charity was dispensed to people of all faiths for, as Bogle explains, he was ‘free from those narrow prejudices which … have opened the most copious source of human misery.’ He himself reveals a less generous heart. Beside the Tibetan penitents, he found India’s Hindus ‘a worthless set of people, devoid of principle.’ But for the lama’s protection, they might have been driven from the palace; yet they were a useful source of information, and the lama was happy if his treatment of them burnished his reputation abroad.

It then emerged that the lama’s mother had been descended from the rajas of Ladakh. The lama himself could converse in halting Hindustani. He dispensed with his translators and discussed the war. Zhidar’s aggression, he said, had been misplaced; he had been over-confident and disinclined to listen. Tentatively, he mentioned that he had fled to Tibet. Bogle explained that, with peace re-established, Hastings had no interest in pursuing Zhidar further. Mutual confidence was established, and the Lama revealed his inner thinking:

‘I will plainly confess,’ said he, ‘that my reason for then refusing you admittance was that many people advised me against it. I had heard also much of the power of the Fringies: that the Company was like a great king, and fond of war and conquest; and as my business and that of my people is to pray to God, I was afraid to admit any Fringies into the country.’[28]

Later, he confided that the heart of the obstruction lay in Lhasa. Bogle was shown a letter from its regent advising that,

… the Fringies were fond of war; and after insinuating themselves into a country raised disturbances and made themselves masters of it; that as no Fringies had ever been admitted into Tibet, he advised the Lama to find some method of sending me (Bogle) back, either on account of the violence of the smallpox, or on any other pretence.[29]

Still, the Lama promised that, at Tashilhunpo, he would introduce Bogle to some Chinese envoys and raise the matter of trade. Bogle understood the risks, but he could hardly object to a proposal that appeared so reasonable.

They moved on to matters of religion. When, the Lama mentioned that some ‘Fringy padres’ had once been expelled from Lhasa for causing a disturbance, Bogle explained that the English were not Catholics; they ‘remained at home … and allowed everyone to worship God in his own way.’ Other topics were less easily parried. Asked to explain the mysteries of the Trinity (or how God could be ‘born three times’), Bogle claimed his Hindustani was not up to the mark. He simply said that ‘God had always existed.’[30]

The Lama then mentioned that, before the twelfth-century Muslim conquest of Northern India, Tibetans had often travelled there, to study Sanskrit scriptures. It would ‘throw great lustre on his pontificate’ if he might build an establishment by the Ganges and restore the link. Indeed, he would write to the Changay Lama, the emperor’s confidant in Peking, suggesting that he request the same. Would the English accommodate his wish? Bogle promised they would.[31]

Beyond religion, the convivial Lama was interested in a variety of topics, not least European science and knowledge. The thread of his enquiries was sometimes unpredictable, matching his curiosity. Bogle was enchanted. He wrote that,

… although venerated as God’s vice-regent through all the eastern countries of Asia, endowed with a portion of omniscience, and with many other divine attributes, he throws aside in conversation, all the awful part of his character, accommodates himself to the weakness of mortals, endeavours to make himself loved rather than feared, and behaves with the greatest affability to everybody, particularly to strangers.[32]

By early December, the Lama was ready to return to Tashilhunpo. The leisurely progress of the grand procession took about a week, with frequent stops for tea and a stay of two days at the Lama’s birthplace. Approaching Tashilhunpo, the governors of Shigatse filed by to pay homage. They presented a remarkable sight. Dressed like women, their whiskers and overgrown carcasses ‘left no room to mistake their sex’:

Their heads were bound with white turbans rolled into a square form; round turquoise earrings, about the size of a watch, hung from their ears, and fell from their shoulders. They wore slippers, and the rest of their dress was of blue satin, with their arms bare to the elbows.[33]

Tashilhunpo was more imposing than Dechenrubje, but it offered ‘nothing but priests; nothing from morning to night but the chanting of prayers, and the sound of cymbals and tabors.’ Spectacles such as the Black Hat dance, which celebrated the assassination of Lang Darma, a ninth-century persecutor of Buddhists, provided entertainment, but Bogle’s stay threatened to pall. One of his more interesting visitors was Debo Dinji, governor of the castle which housed the country’s fiercest criminals. Since executions were prohibited on religious grounds, his policy was to confine the miscreants under his charge without food or drink, and let nature take its course. Bogle judged him ‘a little crack-brained.’ Nevertheless, he says,

I grew very fond of him, and he … took a great liking to me … [But] he was as averse to washing his hands and face as the rest of his countrymen. He happened one morning to come in while I was shaving, and I prevailed upon him for once to scrub himself with the help of soap and water. I gave him a new complexion, and he seemed to view himself in my shaving glass with some satisfaction. But he was exposed to so much ridicule from his acquaintances, that I never could get him to repeat the experiment.[34]

Bogle’s greatest pleasure, however, came from the company of the Panchen Lama’s nephews and nieces. The first, the ‘Pyn Cushos’, had interests that were decidedly secular; the second were merrier than their nuns’ habit implied. Their mother, another nun, had formed a connection with the lama’s brother, a monk, of a sort that ‘put an end to their state of celibacy.’ The Panchen Lama had shunned them until after the husband’s death. When Chum Cusho returned to chastity, he treated her kindly. Bogle found her ‘as merry as a cricket.’

In March 1775, the Pyn Cushos took Bogle and Hamilton on a trip beyond the gaze of their uncle, where they could engage in the hunting and drinking of which he disapproved. Hunting consisted of coursing for hares, shooting partridge and snaring musk deer. Bogle could not speak for the flavour of the partridge: the cook, he says mysteriously, allowed those shot by Hamilton to fly away ‘some hours after they were dead.’ Others were so tame that Bogle felt bound to release them, an act which was judged ‘very pious’.

At their hunting lodge, the Pyn Cushos kept a large parcel of dogs and, at the bottom of the stairs, a wolf and a tiger:

[One] night we were alarmed with a dreadful barking and howling among the dogs, which soon brought all the family together … Mr Hamilton and I in our shirts, the rest with only a blanket wrapped round them, it being the custom for the Tibetans, both men and women, to sleep naked … Some said it was thieves; but as I could not think anybody would be so wicked as attempt to rob the Lama’s family, I had nothing for it but to conclude it was the devil … A most extraordinary yelling began just under our nose … which would certainly have served to confirm my notion, had not the whole family, to my utter astonishment, burst out into a fit of laughing; and, Paima having managed to light a lamp with his tinder-box, we had the satisfaction to see Mr Wolf … pinned down by the tiger cat, with her claws fixed in his cheeks.[35]

When they returned to Tashilhunpo, Hamilton administered to the medical complaints of Dorje Phagmo (‘Durjay Paumo’), the sickly daughter of Chum Cusho’s husband by another wife. She was the most senior of the female incarnations in Tibet, the head of the Samding monastery on Yamdrok Lake. Her greatest exploit was to put some plundering Mongols to flight by using supernatural powers to turn the nuns under her charge into furious sows. Despite her fine features which, uniquely, included hair which she wore in tresses on her shoulders, Bogle found her ‘wan and sickly.’ This he ascribed to her ‘sedentary and joyless life.’ He may not have known that she slept in a seated position, and spent every night in meditation.[36]

Bogle wrote encouragingly to Hastings about Tibet’s potential. Being topographically barren, it required supplies. Its friendly attitude had attracted merchants from all points of the compass: Lhasa was ‘the centre of communication between distant parts of the world.’ Exports of gold, musk, cowtails, wool, and salt were exchanged for silk, rice and tobacco. There was some commerce with Siberia performed by Mongolian Kalmuks, and some with Kashmir. The greatest traffic was with China, whence Tibet imported ‘immense’ quantities of tea, as well as satins, silk, furs, porcelain, glass, and silver. These were paid for with gold, pearls, conch shells, broadcloth and ‘a trifling quantity of Bengal cloths.’ Even so, Bogle was optimistic that there would be demand for broadcloth, coral, and European manufactures. They might be supplied from Bengal by Kashmiri traders, through Bhutan.[37]

By now, however, he also appreciated the Panchen Lama’s battle for influence with the Lhasa regent:

Although he appears to pay great deference to the Lama’s opinion, [Gesub Rimboche] consults him as seldom as possible. The grand object of the Gesub’s politics is to secure the administration for himself, and afterwards to his nephews; while the Teshu Lama, on the contrary, is exerting all his interest at the Court at Peking to procure the government for the Dalai Lama, who is now nearly of age, and to obtain the appointment of a minister devoted to himself.[38]

It was not encouraging that, when the Lhasa envoys were introduced to Bogle, their gifts comprised dried fish, mushrooms, and spirits only. They declared that, as Tibetans were afraid of the heat of Bengal, the custom which ‘would certainly be observed’ was that they would travel no further than Phari. Bogle countered that Tibetans had traded extensively with Bengal in times past, and that the lama was in favour of the practice resuming. The envoys conceded little. ‘The Gesub Rimboche would do everything in his power,’ they said, ‘but he and all the country were subject to the Emperor of China.’ With this they left.[39]

Greatly disappointed, Bogle suggested to the lama that, if the regent was responding to fear of the Gurkha Raja (then assaulting Sikkim), the best way to contain him was to establish a direct connection with Calcutta. The lama agreed, but he warned that the regent was suspicious of the British: ‘his heart is confined, as he does not see things in the same view as I do.’ He also ‘dreaded’ giving offence to the Chinese, to whose empire the country was subject.

At a second meeting, Bogle asked the envoys to relay a letter. They said they would do so only if it thanked the regent for his gift of brandy. With the remark that ‘much conversation’ was not the custom of their country, they took their leave. Afterwards, the Panchen Lama drafted a short epistle which included a request, in Hastings’ name, that Tibetan merchants should be permitted to trade with Bengal. To this, no reply was received. The question of Bogle’s travelling to Lhasa was not even raised, on the understanding that the regent considered him a spy who had come to investigate ‘the nakedness of the land.’ The lama advised Bogle to wait until the Gurkha Raja had been defeated, until he died, or until the emperor had put the government of Tibet into the hands of the Dalai Lama:

[For the Gesub] was formerly and will now be again a little man… [and] then I shall have no difficulty in carrying any point that the Governor (Hastings) pleases, and hope to settle it so with the Emperor that the Governor may send his people to Peking, and, if he pleases establish English factories …

Even so, he cautioned that the next envoy sent from Calcutta should be a Hindu.[40]

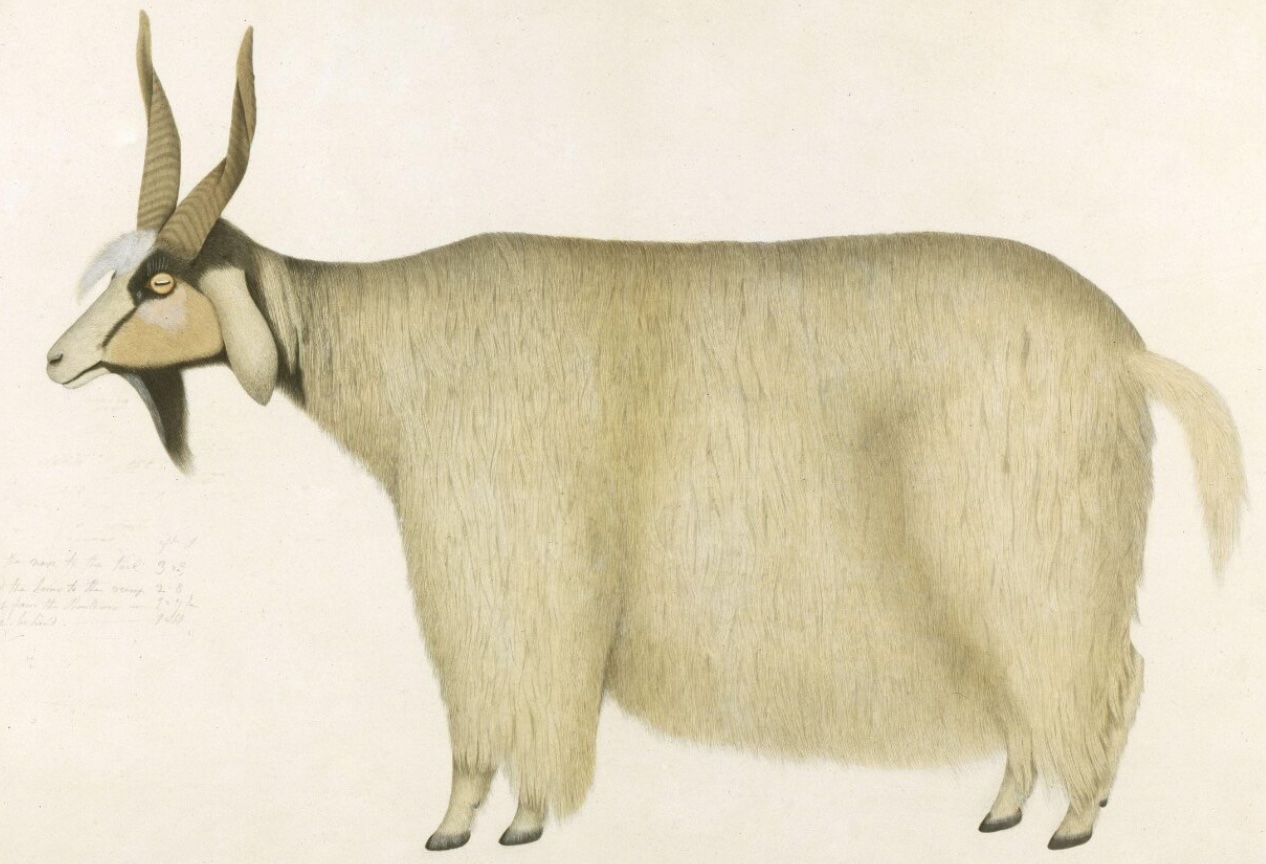

That was as close to Lhasa as Bogle got. There remained time only for farewells, to the Chum Cusho and her daughters, to whom he promised to send parrots and looking-glasses, and to the Pyn Cushos (‘a harder task’). The Panchen Lama promised to send Hastings some musk deer and Kashmir shawl goats (‘tús’). In exchange, he asked for a crocodile and two lions’ skins. Bogle became emotional. He wrote that the lama,

… observed it, and in order to cheer me mentioned his hopes of seeing me again. He threw a handkerchief about my neck, put his hand on my head, and I retired … Farewell, ye honest and simple people! May ye long enjoy that happiness which is denied to more polished nations; and while they are engaged in the endless pursuits of avarice and ambition, defended by your barren mountains, may ye continue to live in peace and contentment, and know no wants but those of nature.[41]

Accompanied by Purangir and Paima, Bogle left Tashilhunpo, on 3 April 1775. Hamilton travelled ahead. Bogle hoped his return visit to Bhutan would be brief: the monsoon was approaching, and he felt ‘out of order’. (His condition was venereal.) At Thimpu, a second round of negotiations lasted a full fortnight: the Bhutanese were as preoccupied with claims over the border villages as they were with trade. The idea that Company employees might have rights of access was quickly abandoned. The desi feared their encroachment, the impact it would have on his trading interest and, especially, on Chinese opinion. The most Bogle could obtain was permission for Hindu and Muslim merchants to pass through Bhutan on their journeys between Bengal and Tibet. In exchange, duties on Bhutanese merchants in India were waived. Tibetan rights were left for the Panchen Lama to negotiate. Trade in sandal, indigo, red skins, tobacco, betel and pan remained the exclusive province of the Bhutanese.[42]

Bogle feared that, with these concessions, he would gain ‘little credit in the world.’ Still, he believed that, if the merchants were encouraged to visit Calcutta in the right season, exports of Company broadcloth would rise. Upon the death of the Gurkha Raja, the Panchen Lama’s influence might be used to open another trade route through Nepal. Hastings, the realist, was satisfied. He had a clearer idea of the situation, and the strength of Bogle’s relationship with the lama offered a platform on which to build. He rewarded Bogle with fifteen thousand rupees. Yet, the initiative stalled. After 1773, a new governing council was established in Calcutta. Hastings’ powers were severely circumscribed. The Tibetan thrust, and Bogle’s career, came to a virtual halt.[43]

Hastings encouraged him to prepare his notes for publication. He even asked his friend, Dr. Johnson, to provide some advice. Appointed Collector at Rangpur, at the foot of the duars, Bogle sat on his hands. Possibly, he was concerned not to inform others of his discoveries before he returned to Tibet. He focused his energies on establishing an annual trade fair, but Hamilton’s reference, in his correspondence, to Bogle’s ‘situation at Melancholy Hall’ hint at depression.[44]

Purangir maintained contact with Tashilhunpo, and Hastings honoured the Lama’s request by allotting some land on the Hugli River opposite Calcutta, for a temple and a traders’ guest house. Decorated with a curious mixture of Hindu and Buddhist images, some of which were supplied by the lama, the Bhot-Bagan (‘Temple-Garden’) was placed under Purangir’s charge.[45]

The Panchen Lama Travels to Peking (1779 – 1780)

While Bogle kicked his heels, Hamilton returned to Bhutan, in 1776. His ostensible purpose was to scrutinise Bhutan’s claims over some Indian border villages, but he had more than half an eye on Tibet. He grew concerned, therefore, when the desi frustrated its merchants from passing through Bhutan. The desi also prevented representatives sent by the Panchen Lama from meeting Hamilton. When, eventually, a letter got through, the lama’s message was that, because of ‘the presence of the Emperor’s vakils … and daily solicitation of the Lhasa Government,’ he was unable to invite Hamilton to Tashilhunpo.[46]

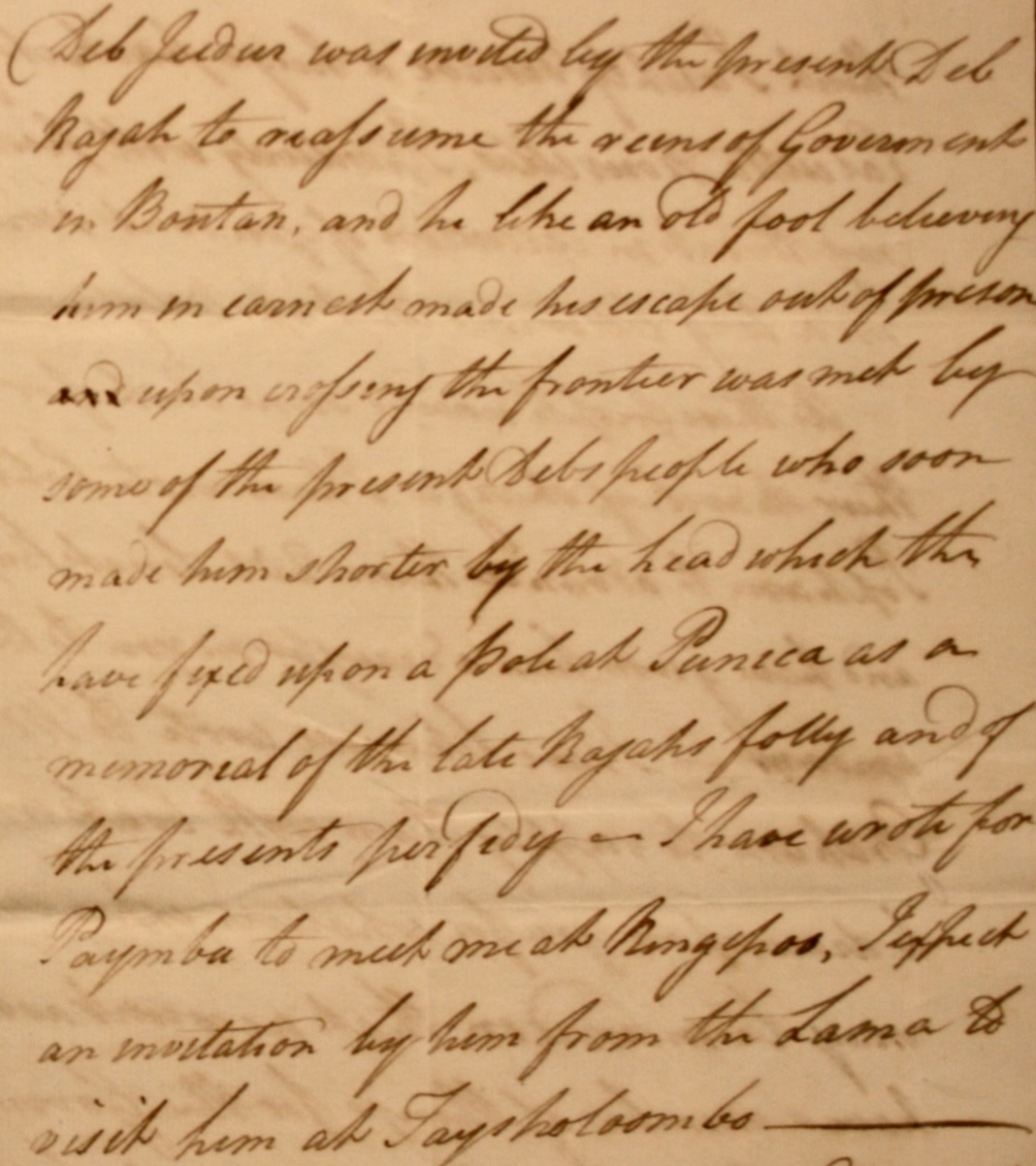

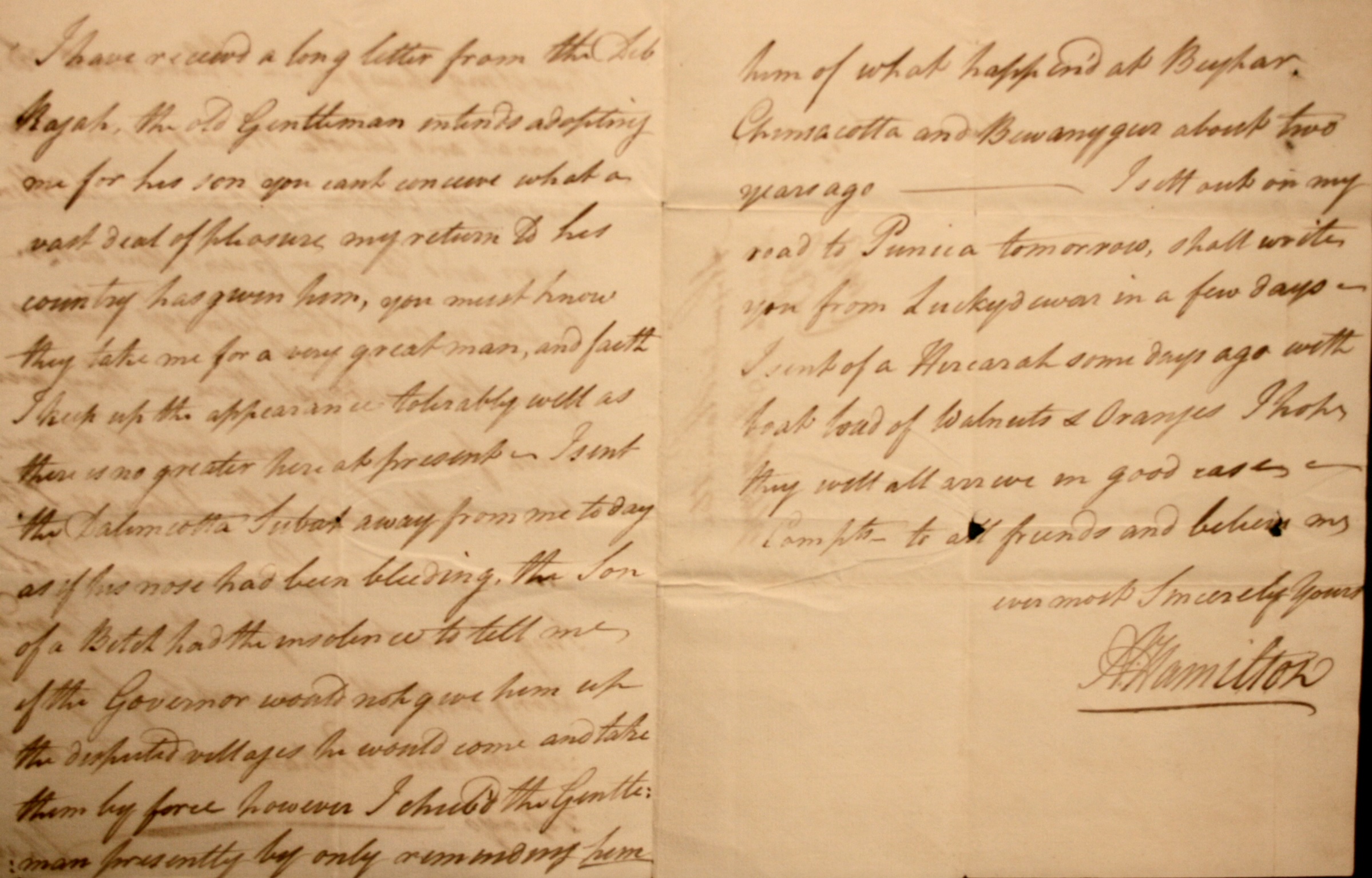

In the boundary disputes, Hamilton found himself opposed on all sides. The arguments became highly charged and, as Bogle realised, the warmth of Hamilton’s temper was ill-suited to diplomacy. In one early letter, he boasted that he had sent away the Dalimkotta subah ‘son of a bitch’, ‘as if his nose had been bleeding,’ for suggesting that, unless the Company surrendered certain territories, he would take them by force. Another official, Ram Kant, was cursed as ‘a liar and a villain’ for giving his superiors false papers. These suggested Hamilton was empowered to settle all of Bhutan’s territorial disputes, rather than just to investigate some. Hamilton declared that, if the desi had not sent a friendly interpreter, ‘I should have been known amongst the Bhutanese by those appellations I so freely bestow upon the Kazi.’

In late 1776 or early 1777, Kuenga Rinchen, died. Bogle’s companion, Jigme Sengay, became desi as well as regent. This promised well for relations, and Hamilton returned to Bhutan for a third time. His trek through the monsoon was extraordinarily punishing. A few miles from Cooch Behar, his porters tossed his baggage into the jungle and ran off. At the first river, he had to abandon his horse and swim. For much of remainder of the journey (on one day from seven in the morning until three hours after midnight), he trudged up to his waist in water. He had earlier recommended that the districts of Ambari-Falakata and Jalpaish should be returned to Bhutan, in exchange for a reduction in duties on goods transiting from Tibet to Bengal. En route, he learned that William Harwood, a Company officer, had ruled against him, in a manner which he believed made hostilities with Bhutan likely. He died, in October 1777, during at epidemic at Buxa Duar, frustrated at having wasted his time in the borderland, ‘where human nature has arrived at a greater pitch of depravity than I have ever elsewhere experienced it, [and] where I am precluded from all communication with the rational part of mankind.’[47]

In April 1779, the news broke that the Lhasa Regent had died and that the Dalai Lama, having reached maturity, had taken up the full exercise of his office. This promised greater influence for the Panchen Lama. Bogle prepared for a second expedition ‘to open a communication with the Court of Peking and, if possible, to procure leave to proceed thither.’ Then, Calcutta was informed that the Panchen Lama had been invited to visit the Qianlong Emperor. Purangir was despatched to Tashilhunpo to obtain permission for Bogle to accompany him through Mongolia, or to join him in Peking from Canton (for whose private merchants he planned to intercede). Unfortunately, before Purangir arrived, the lama departed. Absent a pass, Bogle remained mired in Rangpur.[48]

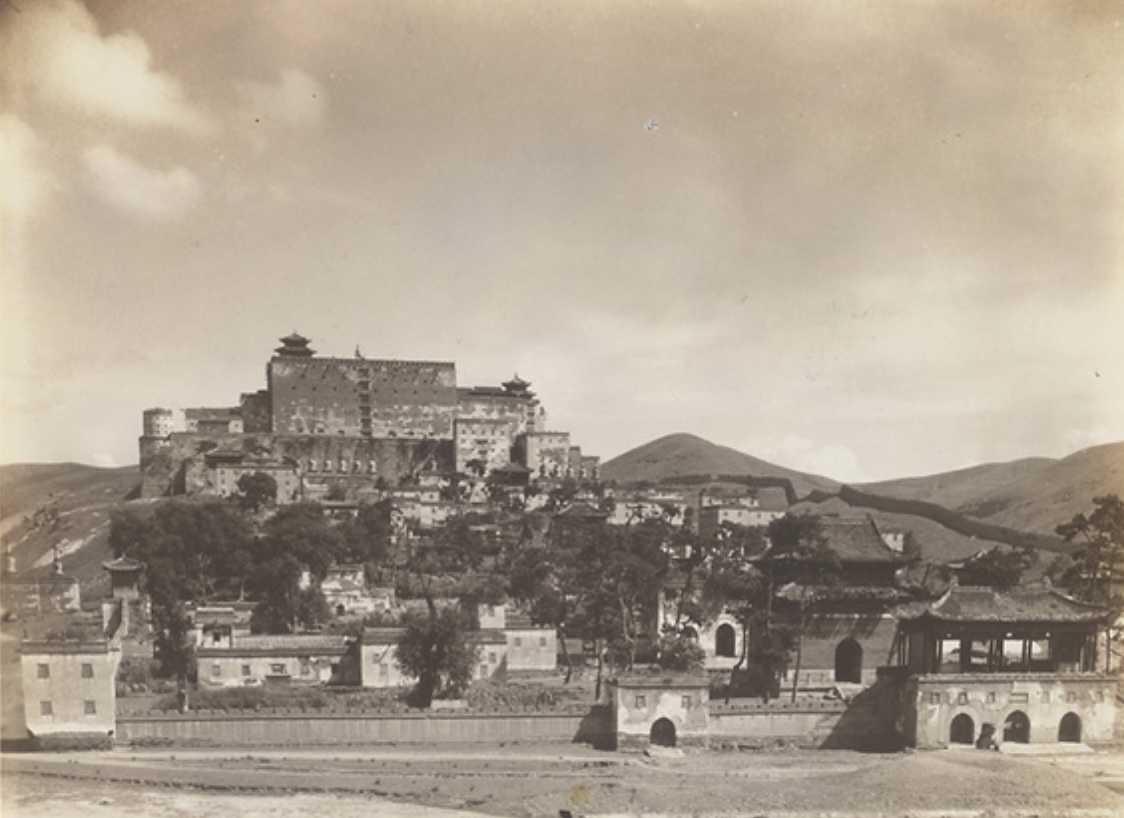

Purangir eventually caught up with the lama at Kumbum (Xining), some 1,250 miles into his journey. In August 1780, after a further thousand miles of travel over barren territory, the caravan reached Jehol (mysteriously ‘Jeeawaukho’ in Purangir’s account). There the emperor had erected the Xumifushou miao, a vast new monastery modelled on Tashilhunpo. (The lama’s arrival coincided with the return, from Russia, of the leaders of the Torguts, a tribe of Mongols who had migrated there in the seventeenth century. No doubt, it was designed to impress them also.)

Much of Purangir’s description of the meetings between the lama and emperor conflicts with the Chinese record. Specifically, he makes no mention of the kowtow:

… the Emperor met him, at the distance of at least forty paces from his throne … and immediately stretching forth his hand, and taking hold of the Lama’s, led him towards the throne, where, after many salutations, and expressions of affection and pleasure, on both sides, the Lama was seated by the Emperor upon the uppermost cushion with himself, and at his right hand.

He says that, a few days later, the Panchen Lama was prompted by the Changay Lama to raise Hastings’ suit, explaining that he was a ‘great prince’ for whom he had ‘the greatest friendship’`:

… if you will write him a letter of friendship, and receive his in return, it will afford me great pleasure, as I wish you should be known to each other, and that a friendly communication should, in future, subsist between you.

Emperor Qianlong was delighted at this idea, Purangir wrote. Later, in Peking, he reportedly confirmed that that it would give him great pleasure to know and correspond with the ‘Governor of Hindustan’,

… and to convince him of his sincerity, he would, if the Lama desired it, cause a letter to be immediately written to the Governor, in such terms as the Lama would dictate …[49]

Purangir was gilding his account. In 1793, Qianlong wrote to King George III, telling him to swear ‘perpetual obedience.’ It is hardly likely that, in 1780, he would have contemplated communicating with one of his minions as a ‘friend’. The Chinese record mentions the Lama’s request not at all. He may have raised the matter. He may have felt obliged to Bogle and Hastings, not least for their assistance with Bhot Bagan. He may have thought that he would benefit personally if the trade were resumed. But he need not have expected the emperor to respond favourably.[50]

Unfortunately, the reports lifted British expectations. So much so that when, in November, the Lama sickened and, as Sopon Chumbo put it, ‘retired from this perishable world to the eternal mansions,’ some said he had been poisoned. Thus, Sir George Staunton. In his account of Lord Macartney’s embassy, he confirmed that the Lama had died from smallpox, but he declared that the suddenness of his demise, and his recent contact with the British, created suspicions that Qianlong had yielded to ‘a policy practiced sometimes in the East.’

Staunton was not averse to blackening the emperor’s reputation. He may also have read a report, in Macartney’s possession, that the poisoning lay behind the sudden flight of the Panchen Lama’s younger brother, Shamarpa, to Nepal. Still, ideas of assassination may be dismissed. In their letters to Hastings, neither Chanzo Cusho nor Sopon Chumbo expressed suspicion, and the Lama’s Tibetan biography nowhere mentions poison. It does not even hint that Hastings was mentioned to the emperor. If he was, it is hard to see why Qianlong, who had deliberately propagandised his relationship with the Panchen Lama, would have murdered him for associating with a power that to him counted for so little.[51]

Samuel Turner and Samuel Davis in Bhutan (1783)

Before news of the Lama’s death reached Calcutta, hopes for Hastings’ initiative suffered another devastating blow. In April 1781, George Bogle drowned whilst bathing in a tank near his villa in Calcutta. He was thirty-four. Already power at Tashilhunpo, and at Lhasa, was accruing to the Chinese. Now Hastings was deprived of the second person central to his purpose.[52]

Then, in February 1782, Purangir reached Calcutta bearing messages of friendship from Chanzo Cusho, now Tashilhunpo Regent, and Sopon Chumbo. Soon afterwards, it was announced that the Panchen Lama had reappeared in the person of an infant. Hastings resolved on sending a mission to welcome him back. To lead it, he selected his kinsman, Samuel Turner. Turner was accompanied by Purangir, Lieutenant Samuel Davis, an accomplished surveyor and draughtsman, and by a surgeon, Robert Saunders.[53]

Before meeting Turner at Rangpur, Davis confided to his journal that he understood the mission ‘intended to the court of Pekin, and that it was meant we should, if possible, go thither.’ He investigated the possibility of returning on the Brahmaputra through Assam, which would have advanced intelligence, but he was advised against it by a German trader, named Raush. A month before, Raush had ventured into the state with Hugh Baillie. Seventy miles from Goalpara, they were turned back by numbers of natives, who gathered at a barrier in the river:

[Davis writes] The natives were armed, and shewed determined resolution to prevent any further approach to the interior of the Country should it be attempted by force, firing several discharges of cannon by way of bravado. The two gentlemen were permitted to go on shore, but received no mark of civility whatever; neither were they admitted to see the principal person stationed at the pass.

Davis speculated that the natives’ attitude derived ‘from their communication with the Chinese.’ Although Raush considered that ‘a regiment of seapoys would be sufficient to effect the conquest of the whole country,’ the idea was abandoned.[54]

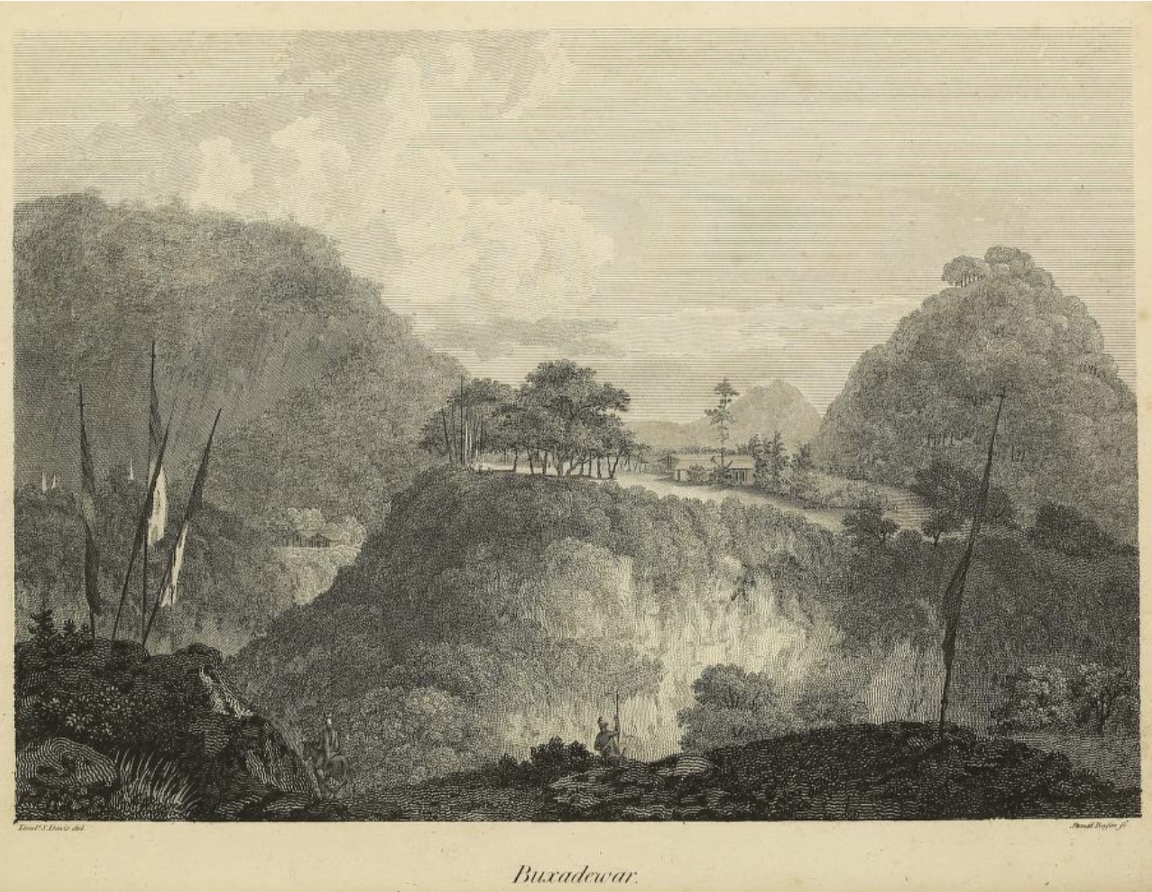

So, the mission followed Bogle’s route to Bhutan through the swampy flats around Chitakota. Here, thick long grass and reeds made passage by palanquin difficult. Perforce, they were abandoned on the climb up the duars. The Englishmen relied on horses, which scrambled up the narrow path between cliff and precipice with ‘amazing agility.’ Davis confesses that he should himself ‘have hesitated at some places, had not a Bootea led the way.’

Near Buxa Duar, they were greeted by a man playing an instrument like a hautboy, some women singing ‘in melodious tones,’ and a messenger sent by its governor. Publicly, Turner described the women as ‘mountain nymphs, with jetty flowing tresses.’ Privately, Davis noted they were ‘not of the choicest class’ and gave him ‘no favourable impression of the ladies of the country.’ Such is the power of the press. Turner looked about for the envoy,

… and was surprised to find him at my elbow; a creature that hardly bore the resemblance of humanity; of disgusting features, meagre limbs, and diminutive stature, with a dirty cloth thrown over his shoulders. He was of a mixed race, between the Bootea and the Bengalee; and it was wonderful to observe how greatly the influence of a pestilential climate, had caused him to degenerate from both.[55]

Turner’s account is of a different temper to Bogle’s. His style is more contrived, but he is not without humour. Davis’s journal is more matter of fact. He wrote that he was impressed by the Bhutanese men, and compared them to the people of the plain in terms similar to Bogle:

I could not help approving the entire contrast exhibited in the appearance, manner and customs of the mountaineer, when compared with their Neighbours in the country below. They differ as widely from them in the manly openness and freedom of their manners, as they do in their superior size and manliness of their forms.

As they took refuge in a house from a group of dirty villagers, whose curiosity had ‘brought them to windward,’ Turner and Davis were first joined by some officials. They were entertained with butter tea and warm chhang beer, which Turner considered a ‘most grateful beverage.’ The soobha, when he appeared, was a friendly soul, curious about Turner’s telescope, and his guns. He enjoyed his beer, claret, and Madeira, as well as chess, cards, and backgammon. When Davis shot a crow, he did not complain; he considered crows ‘mortal enemies’ to the strings of raw meat which he hung out in the sun, to develop an ‘irresistible’ odour. Nor did he object to Davis reaching for his paints.

To avoid the appearance of sketching ‘by stealth’, he started by drawing the soobha’s house, in full view of his window. This drew the inevitable enquiry. The governor was impressed by Davis’s accuracy, but particularly by a view of Calcutta, which he studied through a glass given to him by Turner. With it he also inspected the frontispiece to a number of Bell’s British Theatre. The picture of an actress portraying Queen Artemisia drew the exclamation, ‘How small about the waist, and what a vast circumference below!’[56]

After dinner, there followed a competition of archery and shooting, at which the soobha proved himself ‘a tolerable marksman.’ Davis writes,

[The Bhutanese] express their acclamation at a dextrous shot by leaping and throwing their arms about in a sprawling manner, accompanied at the same time with a wild yell, which may be used with propriety in war to intimidate the enemy.

Today, whether at archery or their peculiar game of khuru, the Bhutanese continue to celebrate their better shots with much good-natured singing, dancing and arm waving.

After a few days, the party continued to Jaigugu and Muri-jong. On their right, the river ran through mountains ‘seemingly rent asunder to give it passage.’ In places, on the edge of the precipice, the trail, which was as a little as two feet across, was held in place by the roots of trees and shrubs. Later, it ascended the face of a cliff, on which the attendants and baggage ‘had the appearance of ants crawling in traverses across a wall.’ Kepta had an impressive looking dzong, though, on closer inspection, Davis considered its walls might ‘be laid flat with a club.’ Thereafter, the land took on ‘a more social aspect.’ Lofty houses set amidst terraced fields lacked only chimneys and mortar to be comfortable. On 1 June, Tassisudon came into view, and the party was received by Jigme Sengay.[57]

After an exchange of civilities, scarves, and gifts, they had a cup of tea. The role of the taster was just like that mentioned by Bogle at his reception by Kuenga Rinchen, though Turner, who was as unconvinced by its savour as by the ceremony of using tongue and rag to clean your cup afterwards, refers explicitly to the ‘treacherous use of poison.’ We then learn that what applied to tea applied also to Saunders’ ipecacuanha, an emetic, of which ‘it being rather tardy in its operation,’ the inquisitive Jigme Sengay took a larger dose than was wise. For the space of two days, ‘it kept him in perpetual agitation’ and, presumably, his physician as well.[58]

Despite this, Jigme Sengay and Saunders formed a good relationship. It was born of the desi’s natural curiosity and Saunders’ respect for Bhutanese practice. He was impressed by the variety of aromatics and herbs that the Bhutanese used in the treatment of ailments, their skill in bleeding, and their approach to dealing with smallpox. The practice of inoculation was in its infancy and Saunders was unconvinced by its usefulness. Like the Bhutanese, he believed that instead of attempting to cure the infected, it was best to prevent all contact with them, ‘even at the risk of their being starved,’ and to destroy with fire their houses or villages after they had died. In Bhutan, he confirmed, ‘the disease is very seldom to be met with, and its progress always checked, by the vigilance and terror of the natives.’

Davis reported the surgeon’s surprise at seeing ‘a difficult case of a fractured skull treated … with great propriety.’ He wrote that ‘the same operator gave a very satisfactory account of the use he made of mercury in venereal disorders.’ Saunders donated some modern lancets, for use in cupping, and suggested improvements in the way the Bhutanese might treat dropsy. In exchange, he was given samples of seventy different medicines. Davis refers to a book comprehending all of Bhutanese practice. It was printed on long slips of paper bound between flat boards ‘ornamented according to the value they contain.’[59]

Although he barely mentions it, Turner was apparently instructed by Hastings to offer Amabari-Falakata and Jalpaish to Bhutan in exchange for co-operation on trade. This may have eased relations. Irrespective, Jigme Sengay was as friendly as ever. He claimed to have with Hastings ‘the nearest spiritual alliance.’ Indeed, he went further,

… rejecting every degree of mortal relation, [asserting] theirs to be no other than emanations from the same soul … embracing, in one comprehensive system, the immaterial spirit, or animating principle of all the good and great, unconfined to place, to nation, or religion.[60]

So accommodating was he that, when peace was disturbed by a revolt by the dzongpen of Wangdi Phodrang (‘Wandepore’), the British were permitted to observe the proceedings. On 25 June, reports were received that Punakha was threatened, and reinforcements were sent for its defence. As Jigme Sengay then marshalled the farmers of the district for the defence of Thimpu, the rebels seized some of its neighbouring villages and took up a position opposite the dzong. The population collected provisions for a siege, and stones to throw at the enemy, and retreated behind its walls.

Turner was concerned that his residence, which was prominent, would attract especial attention. He need not have worried. A few days before, the dzongpen had sent him a basket of fruit, with a letter expressing his regret that ‘urgent business at present prevented his seeing one who had come so great a distance.’ He was not a target, and his balcony afforded him a grandstand view.

On 27 June, Davis believed he saw opportunities which might have brought the loyalists victory. But ‘it was not their fighting day.’ They moved out in a throng observing no sort of order while, in the field, each man acted ‘according to his own courage and opinion.’ Fortunately, the opposition showed little interest in coming to quarters. Instead, they fired their matchlocks at a distance, and bullied each other, ‘hollowing, leaping, and flourishing their swords, until 5 o’clock, when both sides withdrew to their victuals.’

The next day, Jigme Sengay asked for advice on how best to deploy his cannon. These were old swivels carrying a one-pound ball only, which meant they were bound to disappoint, as the desi wished them ‘to beat the houses about [the rebels’] ears.’ Davis mentioned that the two barrels, which were buttressed simply with stones, would leap around less, if they were secured to carriages. Then, he noticed that they were ‘crammed with powder and shot, almost full’ and that the honeycombed barrel of one had holes large enough to admit an egg. In that state, they posed the greatest risk to the person who lit the fuse. As he struggled to phrase a response that would not cause offence, there was a pealing of bells, and a desultory fire commenced. It lasted for two hours. Both sides meticulously avoided presenting a target. According to Turner, little was visible but ‘the top of a tufted helmet, or the end of a bow.’

By noon on 28 June, Jigme Sengay’s forces had been reinforced, and revivified with a substantial meal and quantities of chhang. The rebels were running short of ammunition. At the end, they ‘were obliged to resort … to pelting their adversaries with stones’:

… the contest was carried on till about five o’clock, when the loyalists forced the rebels from the centre village … Soon afterwards a parley took place … The conference lasted more than twenty minutes …and the insurgents … went off in a confused crowd to the south. Nearly at the same time the western village was also abandoned; and no magic exhibition could display a more sudden and striking change of scene. In an instant the whole plain, and the rice fields, were covered with an innumerable host … yet on the part of the victors there was no pursuit.

After an hour, the Englishmen walked over the battleground. There was little sign of damage. Few lives had been lost and there were just a few prisoners, although some had been badly injured. Women, children and pigs were enjoying ‘full and quiet possession.’ The Bhutanese were undoubtedly strong and hardy, but to Turner the conflict suggested ‘a very mean idea of their military accomplishments.’ He put it down to a lack of discipline and tactics, and to ‘utter inexperience of war.’ According to Davis,

The enemy left one dead in the field, and three of the rajah’s men were wounded with bullets, but not dangerously. Four horse, and five or six prisoners were taken together with their trophies. Two of them were small white flags and the other a religious ensign. These were brought into one of the squares of the castle, where the champion who carried the last made a speech and flourished his sword dancing all the time in antic gestures. This done, the spectators set up their war whoop and the bells and drums were added to the clamour. The warriors then arranged themselves in ranks, sitting on the Pavement, and were regaled from four large cauldrons of liquor placed ready for the purpose; the Rajah all the time looking graciously on from a window above.

The next morning, the Englishmen congratulated Jigme Sengay on his success. He in turn,

… expatiated on the excellency of the Boutan weapons, shewed us a variety of them, and told a story of a seapoy’s musquet having been cut through with a stroke of a Bootan sword.

The rebels retreated to Wangdi Phodrang dzong, where there was a brief siege. An advanced party of loyalists diverted the stream which supplied the castle with its water, although Davis comments this ‘could have distressed the Garrison no further than by obliging them to fetch it from one of the rivers at the bottom of the hill.’ Even so, the rebels (Davis suggests there may have been three thousand) quickly became disconcerted by the numbers ranged against them, some of whom had switched from their own side. They stripped the monastery of its most valuable ornaments and fled under cover of night, using the bridge over the lesser river, on which the loyalists had set no post.[61]

After an uncomfortable stay in a Wangdi house, which offered poor protection against the ‘perpetual hurricane’, and whose previous occupants, the rebels, had left behind a population of vermin ‘as active in their ravages as the busiest followers of a camp’, Turner’s party were invited to visit Punakha unaccompanied. This was an unexpected privilege. The dzong was the desi’s winter residence, as it enjoyed a warmer climate, and it was reportedly the most richly decorated in the country. They were greatly disappointed, therefore, when, as a result of the recent disturbances, a zealous guard refused them admission. The party had to content themselves with viewing the outer court and the palace’s well-stocked garden.

Davis noticed that the floor of the court had been raised twenty to thirty feet above the surrounding ground, though loopholes in the outer wall betrayed the existence of storerooms at a lower level. Putting on his military hat, he doubted the walls could be breached with any artillery that might readily be brought to bear. The front gate, however, was much more vulnerable. Using a petard to break it open, he explained, would be ‘neither difficult, nor dangerous, the entrance to this, as to other castles in Bootan, being … not flanked or defended by any part of the building.’[62]

There were further meetings with Jigme Sengay. At one, Turner demonstrated a kind of electrical hand grip, and the desi amused himself by inducing unwilling volunteers to receive a shock. At another, in an exchange over geography, he explained that, somewhere to the north of Assam, there lived a species of human equipped with a short inflexible tail. This required them ‘to dig holes in the ground, before they could attempt to sit down.’ He also claimed that his menagerie included a horse with a horn like a unicorn’s. Unfortunately, it was too far distant to permit inspection.

Of the Desi, Davis wrote,

His face is wrinkled by time, and his cheeks are fallen in, but there is something penetrating in his eye and an expression of sense and cheerfulness in his countenance altogether. I do not however conceive him to be a man of first rate abilities, but imagine him to have acquired popularity more from a steady uniformity of character, and a mildness of disposition, than from any ascendency of genius. He still retains the air of the priest than of the monarch, and, if I judge right, values himself more upon his religious than his political pre-eminence.[63]

On one occasion, when discussing the mission’s onward journey, Jigme Sengay offered his sympathies: he knew the road was difficult, as he had himself travelled to Lhasa, as a common mendicant. Turner was astonished that he had not allowed himself a greater measure of comfort, but accepted that the purpose of his journey required him to adopt ‘some degree of penance.’ Davis was more cynical: the desi said he was absent for just ten days, ‘though the distance is twenty days’ journey in common travelling, and though he went on foot from the frontiers of his own dominions.’ He concluded therefore that ‘the whole was a pious fraud.’ He was not to know that, in 1788, after being saddened by the factionalism at court, Jigme Sengay quit as desi, and made a second pilgrimage to Tibet, where he died, in 1789.[64]

After three months, Turner, Saunders and Purangir departed for Tibet. Davis stayed behind. The Tibetans said they may not admit more Europeans than before, but they probably knew of his surveying skill, which precluded him from continuing. Much of the remainder of his Description of Bhutan comprises comments on Bhutan’s government, priesthood and religious practice. In addition, he described the seven-day festival (tsechu), which takes place at Thimpu, in September.[65]

This began with three days of dancing, performed by the monks within their quadrangle of the palace (dromchoe). Proceedings started when a group of them, wearing broad-brimmed hats with tassels behind, danced in concentric rings to the sound of drums and cymbals. This was followed a masquerade featuring a figure representing ‘the destroying power’, who wore a mask ‘grimly enraged and surrounded with skulls.’ Progressively, he was joined by six others similarly dressed, then by one with a mask like a frog and another with a face ‘not unlike a sign painter’s representation of the full moon.’ The music became deeper-toned and more terrific. At the end, the actors gathered around a vessel placed in the middle of the courtyard and exercised for an hour, rather as witches round a cauldron.

Over the next two days, the number of dancers who joined the central figure increased to thirteen, five wearing the mask of hogs and tigers, the others sporting ‘monstrous gaping beaks.’ The music, Davis suggested, was ‘well adapted to make such devils dance.’ On the fourth day, the dancing was opened to the public, and the young lama incarnate, a child of about seven, was brought into the arena on the shoulders of a priest. The climax of the festivities was on the seventh day. This featured the appearance of the ‘Superior Deity’, as ‘Wizie Rimbochy’, before whom sixteen figures, impersonating females, and wearing gilded coronets and long tresses of hair, stepped gracefully, beating tambourines:

They … sung something like a hymn, occasionally separating and returning again to the same position, after bowing and falling on their knees in adoration. They retired for a while, and came out again with rattles in their hand, instead of the tabrets, and continued in the same movements until Wizie Rimbochy and his attendants advanced and took another circuit of the square, the different masks flourishing about at the same time according to their respective characters.

Undoubtedly, the spectacle was highly theatrical, but Davis confessed to having no strong idea of what it signified:

[The Rajah] did not seem willing to enter upon an explanation of what had been exhibited, and the account given by others was neither satisfactory nor perfectly intelligible, but by what little could be gathered from them it has an allegorical meaning which refers to some former calamity, when the country was invaded and the inhabitants devoured by monsters, such as they imitate in masquerade, commissioned by an adverse Deity for this mischievous purpose. On the interposition of Wizie Rimbochy, compassionate of the people’s sufferings, and at their humble supplication, these plagues were withdrawn.[66]

Davis ends by remarking that the Bhutanese often spoke of monsters and flying dragons, one of which was sometimes seen upon a rock near Punakha:

… the Rajah’s interpreter told me very gravely that a young one of the same breed had been caught upon a mountain, and was still kept carefully by the Gylongs among the sacred things in the chapel.[67]

Overall, Davis doubted whether the practice of monkish celibacy was best suited to Bhutan’s development, or to its female population. With its abolition, he believed,

The common people … would be relieved from an unequal share of the concern of prolonging the race, which from time immemorial has been imposed as a drudgery on the lower classes … The women would undoubtedly incline to favour that party whose object it was to relieve them from the degraded condition they now universally suffer, and … to make them partners in such comfort, conveniences, and happiness as the country affords.[68]

Davis pitied young boys for the lives they led in the monasteries. Most, he thought, ‘passed their time with perfect insipidity’ as, between the hours of their devotions, they were generally seen ‘lolling over the balconies of their apartments.’

It seems necessary [he decided] that they should be admitted at such a young age, that by early habit they may be taught to endure the dull tasteless life they have to undergo.[69]

On the other hand, he praised the Bhutanese for their tolerance of other codes of worship, and for the sincerity of their behaviour, which he thought incompatible with despotism. The principle of the reincarnation of the leading lamas, he thought, might have originated to inflict upon the faithful a kind of tyranny. But Tibetan temporal power in Bhutan had weakened, and he doubted that the young lama would ever be able impose himself in that way. Within Bhutan, the fate of Zhidar had shown that,

… from the natural free spirit of the people, unbroken by tyranny, and from the respect that is due to the good opinion and venerable characters of the principal Gylongs, it would be impossible for [the rajah], were he so disposed, to persevere in any flagrant acts of injustice or dangerous schemes of ambition.[70]

Jigme Sengay, certainly, was a most unlikely despot. He appeared in public without parade, and ‘would be taken rather for the master of a great family than for an independent prince.’

More generally, the shortage of coin in circulation was a disincentive to vice, as it made it difficult for the country’s governors to conceal the accumulation of wealth. In any event, the structure of society was such that wealth could not be used by its possessors to rise above the ranks assigned to them by their class. In conclusion, Davis believed the Bhutanese to be ‘an exceeding poor but comparatively speaking a happy people, neither in danger of any very outrageous oppression at home, nor of invasion and slavery from abroad’:

The nature of their government, entrusted to a set of men who can never have mischievous, sinister, and self interested schemes of ambition or avarice to prosecute at the expense of the public, exempts them from the first, and the strength of the country, in the uncommon difficulty of the roads, secures them from the second.[71]

All the same, Davis was sceptical about Bhutan’s potential for development. The influence of the priesthood was positive for stability, and for freedom from corruption, but it was not conducive to economic improvement ‘by arts, manufactures, or commerce.’ Such iron as Bhutan possessed paled into insignificance compared to India’s, and its rivers were ill-suited to the transport of materials such as timber. Davis suggested that the best the men could do was offer themselves as soldiers in India, as they were well-suited physically, and the Bhutanese would benefit from their experience for their own defence.[72]

During Davis’s time in Thimpu, the desi remained approachable, and Davis met him more than once. On one occasion, as they talked over the Buddhist system of the universe, he was told that the Supreme Being, and those worthy of the blessing, dwelt in a celestial region situated on the summit of an immense, square rock, composed of crystal, ruby, sapphire and emerald. Naturally, this gave rise to questions about heaven:

… the Rajah said he had been there, but his manner of expression seemed to indicate a desire to put an end to that topic of discourse, under an apprehension perhaps, that he might be asked to give an account of his adventures on the expedition.[73]

Probably because he detected Davis’s scepticism, the desi was happier discussing ‘trivial’ matters such as painting. Davis gave him a box of colours, and in exchange, he received a dagger. Before departing, he promised to send from Calcutta a time piece, to help regulate Jigme Sengay’s devotions. He said he would write regularly. Then he returned to India, as he had come. Near Chukha, he tried his hand at a hoop bridge across the river, which Turner had been unable to look at ‘without shuddering’, and pronounced it ‘very easy’. Then, at Buxa Duar, he was joined by his friend, the soobha, to whom he gave a suit of linen and an old regimental coat. In that, the governor joined Davis for an evening drink of his favourite, Madeira. The following morning, they enjoyed a contest of archery, before the Englishman left for Bengal.[74]

Samuel Turner in Tibet (1783-1784)

Meanwhile, Turner and Saunders travelled via Paro to Phari, where they lodged in the monastery, as the guest of its lama:

[Turner writes] Time had deprived our friend of half his teeth, and those which remained, kept no good neighbourhood with each other. He had numerous infirmities; shortness of sight, rheumatic pains, and bad digestion … He endeavoured to trace out the sad catalogue of his complaints to Mr. Saunders, who humanely consoled him with his good counsel and medical advice; and I had the good fortune to alleviate one grievous evil, by presenting him with a pair of spectacles.[75]

After two weeks, they reached Tashilhunpo and delivered Hastings’ letter. Regent Chanzo Cusho thanked them and referred to the Panchen Lama’s earlier efforts to intercede with the emperor. Yet Peking had insisted that his young incarnation was to be educated in the strictest privacy. No ‘strangers’ were to be admitted to his presence. (Solpon Chumbo explained how difficult it had been even to admit the British to Tashilhunpo.) They appeared averse to conceding dependence on China, but Turner felt they were in awe of the emperor, and of the Lhasa regent, who had usurped most of the Dalai Lama’s temporal power. Turner was convinced that the interference of the Chinese grated:

… their uneasiness under the yoke … was manifest, from the distant reserve with which they treated those officers and troops, who came for no other purpose than to do honour to their high priest. They were not suffered to lodge within the confines of the monastery … for they look upon the Chinese as a gross and impure race of men. They were evidently impatient during their stay, and assumed an unusual air of secrecy … until the day of their departure, which was announced to me, by many persons belonging to the monastery with much apparent satisfaction.[76]

In the circumstances, there was little chance of progress in trade, and no prospect of reaching Lhasa. Yet, once the Chinese had gone, Turner obtained his hoped-for interview with the infant Panchen. (The regent kept out of sight.)

The little Lama’s eyes were scarcely ever turned from us, and when our cups were empty of tea, he appeared uneasy, and throwing back his head, and contracting the skin of his brow, continued to make a noise, for he could not speak, until they were filled again …

I briefly said, that ‘the Governor General, on receiving the news of his decease in China, was overwhelmed with grief and sorrow, and continued to lament his absence from the world, until the cloud that had overcast the happiness of this nation, was dispelled by his reappearance, and then, if possible, a greater degree of joy had taken place, than he had experienced of grief, on receiving the first mournful news …’

The little creature turned, looking steadfastly towards me … and nodded with repeated slow movements of the head, as though he understood and approved every word.[77]

Even the Tibetans were moved. The official record says,

Although (the British) were not knowers of the niceties of religion, by merely gazing [at the Lama] an irrepressible faith was born in them, and they said: ‘In such a little body there are activities of body, speech and mind, so greatly marvellous and different from the others!’ Thus they said with great reverence.[78]