When one considers that, in the Atlantic, the early voyages of the English were to ‘New Found Lands’, and that to Europeans much in the Indian Ocean had long been familiar; that Eastern commerce was the objective and that the Portuguese had long shown how it might be obtained, it begs the question why the English took so long to attempt the most obvious route to it. After all, the Company’s First Voyage left England in 1601, 103 years after Vasco da Gama anchored off Calicut, and 104 years after John Cabot had shown that an English ship was capable of crossing the oceans to another continent.

Legstretchers on the Road to Persia and India

Thomas Coryate, John Mildenhall and the Sherley Brothers (1598-1627)

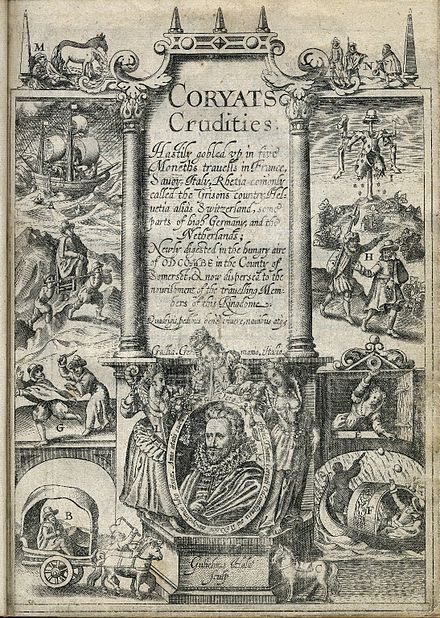

A portrait of Thomas Coryate with representations of France, Italy and Germany, the last of which is puking on his head. (From the frontispiece to the Crudities.)

‘He is an Engine, wholly consisting of extremes, a Head, Fingers, and Toes. For what his industrious toes have trod, his ready Fingers have written, his subtle head dictating,’ wrote Ben Johnson, in his character sketch.

He added, ‘He is a great and bold Carpenter of words, or (to expresse him in one like his owne) a Logodaedale: which voice, when he heares, ‘tis doubtful whether he will more love at the first, or envy after, that it was not his owne. All his Phrase is the same with his manners and haviour, such as if they were studied to make Mourners merry: but the body of his discourse able to break Impostumes, remove the stone, open the passage from the Bladder, and undoe the very knots of the Gout; to cure where even Physick hath turned her back, and nature hung downe her head for shame; being not only the Antidote to resist sadness, but the Preservative to keep you in mirth, a life and a day.’

The full frontispiece to the 1611 edition of Coryat’s Crudities.

To aid his readers in its interpretation, Coryat provided a guide, entitled ‘Certaine opening and Drawing Distiches, to be applied as mollifying Cataplasmes to the Tumors, Carnosities, or difficult Pimples, full of matter, appearing in the Authors front, conflated of Stiptike and Glutinous Vapours arising out of the Crudities; The heads whereof are particularly pricked and pointed out by letters for the Readers better understanding.’

A (upper left): First, th’Author here glutteth Sea, Haddocke and Whiting

With Spuing, and after the world with his writing …

E (lower mid-right): Here to a Tutch-hole he’s row’d by his Gondolier

That fires his *Linstocke, and empties his Bandolier …

F (bottom right): Here shee pelts him with egges, he saith, of Rose water

But trust him not Reader, ’twas some other matter …

*That is, the beauty of her countenance, and sweet smatches of her lips did enflame his tongue with a divine & fierye enthusiasme, and emptyed the Bandolier of his conceipts, & inventions, for that time.

A reconstruction of a sixteenth century chopine (chapiney), from the shoe museum in Lausanne. They were worn by ladies to protect their attire from the filth in the streets.

When Coryate encountered them in Venice, he was unimpressed, writing, ‘… so uncomely a thing (in my opinion) that it is pitty this foolish custom is not cleane banished and exterminated out of the citie. There are many of these Chapineys of a great height, even half a yard high … All their Gentlewomen, and most of their wives and widowes that are of any wealth, are assisted and supported eyther by men or women when they walke abroad, to the end they may not fall …For I saw a woman fall a very dangerous fall, as she was going down the staires of one of the little stony bridges with her high Chapineys alone by her selfe: but I did nothing pitty her, because shee wore such frivolous and (as I may term them) ridiculous instruments, which were the occasion of her fall.’

Coryate with a Venetian courtesan – an engraving from the Crudities.

Of the courtesans in Venice, Coryate tells us ‘It is thought there are of them in the whole City and other adjacent places, as Murano, Malomocco, &c. at the least twenty thousand, whereof many are esteemed so loose, that they are said to open their quivers to every arrow.’

He was told their establishments were tolerated, ‘First, ad vitanda majora mala. For they thinke that the chastity of their wives would be the sooner assaulted, and so consequently they should be capricornified … were it not for these places of evacuation … The second cause is for that the revenues which they pay unto the Senate for their tolleration, doe maintaine a dozen of their galleys … and so save them a great charge.’

Coryate was much taken by the Great Tun in the Castle of Heidelberg. It had a capacity of between twenty-four and twenty-seven thousand gallons and, he says, the wine inside it was worth £1,999. 8s. 0d. Later, in Frankfurt, he bought an illustration of it, which was adapted to show Coryate himself standing atop, with a wine glass in hand.

Coryate wrote of his experience, ‘… the gentleman of the Court accompanied me to the toppe together with one of his Cellerers, and exhilarated me with two sound draughts of Rhenish wine … But … I advise thee if thou dost happen to ascend to the toppe thereof to taste, that in any case thou dost drinke moderately, and not so much as the sociable Germans will persuade thee unto. For if thou shouldest chance to over-swill they selfe with wine, peradventure such a giddinesse wil benumme they braine, that thou wilt scarce finde the direct way downe from the steep ladder without a very dangerous precipitation.’

On his return to Odcombe, Coryate placed the clothes he had worn on his travels in the church, as a memorial. They received a mention in the frontispiece to the Crudities:

‘Old Hat here, to me Hose, with Shoes full of gravell,

And louse-dropping Case, are the Armes of his travell …

In his ‘panegyric’ to Coryate, in the same work, Thomas Farnaby referred to them also:

‘Which shirt, which shoes, with hat of mickle price,

His fustian case, shelter for heards of lice …

Hang Monuments of eviternall glory, at

Odcombe, to th’honour of Thomas Coryate.’

Alas, the original clothing has long succumbed to the passing of the years. In their stead, this pair of stone shoes now decorates the wall of Odcombe’s church of St.Peter and St.Paul.

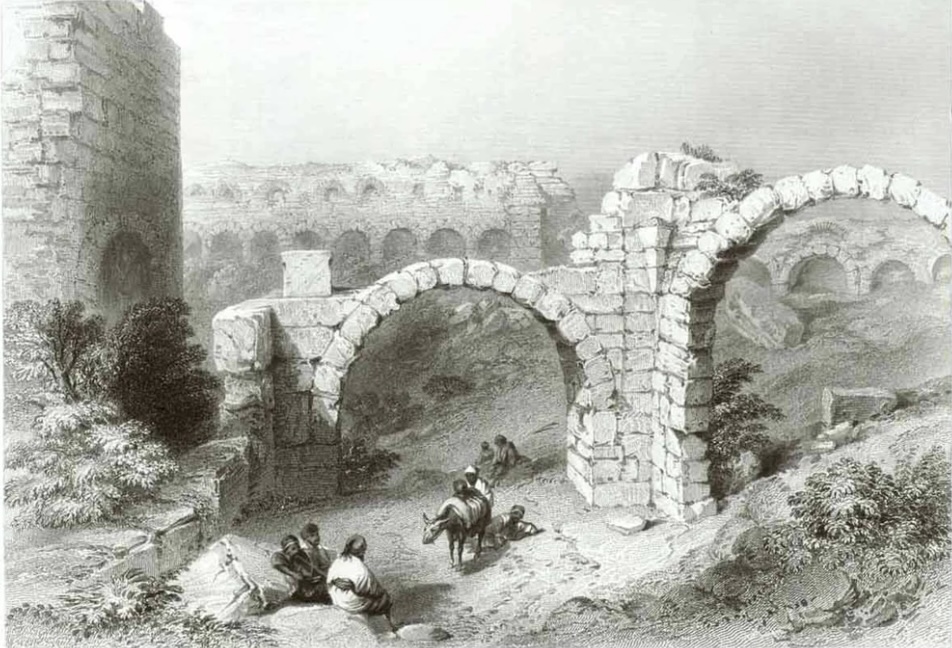

An early nineteenth century view of Alexandria Troas, by R Wallis after WH Bartlett.

Thinking that he was standing at the remains of Troy itself, Coryate ended his oration over these ruins with a moral for the people of London: ‘You may also observe as in a cleere Looking-glasse one of the worst pregnant examples of Luxurie, that ever was in the World in these confused heapes of stones … For Adulterie was the principall cause of the ruines of this Citie, which is well knowne to all those that have a superficial skill in Historie, by the remembrance whereof I … beseech the great Jehovah … to avert the punishment from our new Troy … which I thinke is as much polluted and contaminated with extravagant lusts, as ever was this old Troy.’

At his death, John Mildenhall was buried in the Roman Catholic cemetery in Agra. The tombstone marking the spot was discovered in 1909 and remains in a good state of preservation. The Portuguese inscription reads, ‘Joa de Mendenal, Ingles, moreo aos 1[ d]e Junhou 1614.’ It is, in all probability, the oldest English monument in India. The tablet with the English inscription was added later.

Wiston House, mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Wistanestun’, was acquired by Sir Thomas Sherley, in 1573. The house he built was much larger than today’s, and the cost effectively bankrupted the family. During the Civil War, it was occupied first by royalists and then by parliamentarians. At its end, it was sequestrated by Parliament and bought for a song by John Fagge, a parliamentarian commander.

It was remodelled in 1839 by Edward Blore, served as the Canadian Army’s HQ before D-Day and, since 1951, has been used by the British Foreign Office.

In his Worthies of England, Thomas Fuller wrote of Sir Anthony Sherley’s expedition against Portuguese assets in Equatorial Guinea (1596):

‘His design for St. Thome was violently diverted by the contagion they found on the south coast of Africa, where the rain did stink as it fell down from the heavens, and within six hours did turn into maggots. This made him turn his course to America where he took and kept the city of St Jago two days and nights with two hundred and eighty men (whereof eighty were wounded in the service), against three thousand Portugals. Hence he made for the Isle of Fuego, in the midst whereof is a mountain, Aetna-like, always burning; and the wind did drive such a shower of ashes upon them, that one might have wrote his name with his finger on the upper deck …

Now although some behold his voyage, begun with more courage than counsel, carried on with more valour than advice, and coming off with more honour than profit to himself or the nation (the Spaniard being rather frighted than harmed, rather braved than frighted therewith); yet impartial judgments, who measure not worth by success, justly allow it a prime place amongst the probable (though not prosperous) English adventures.’

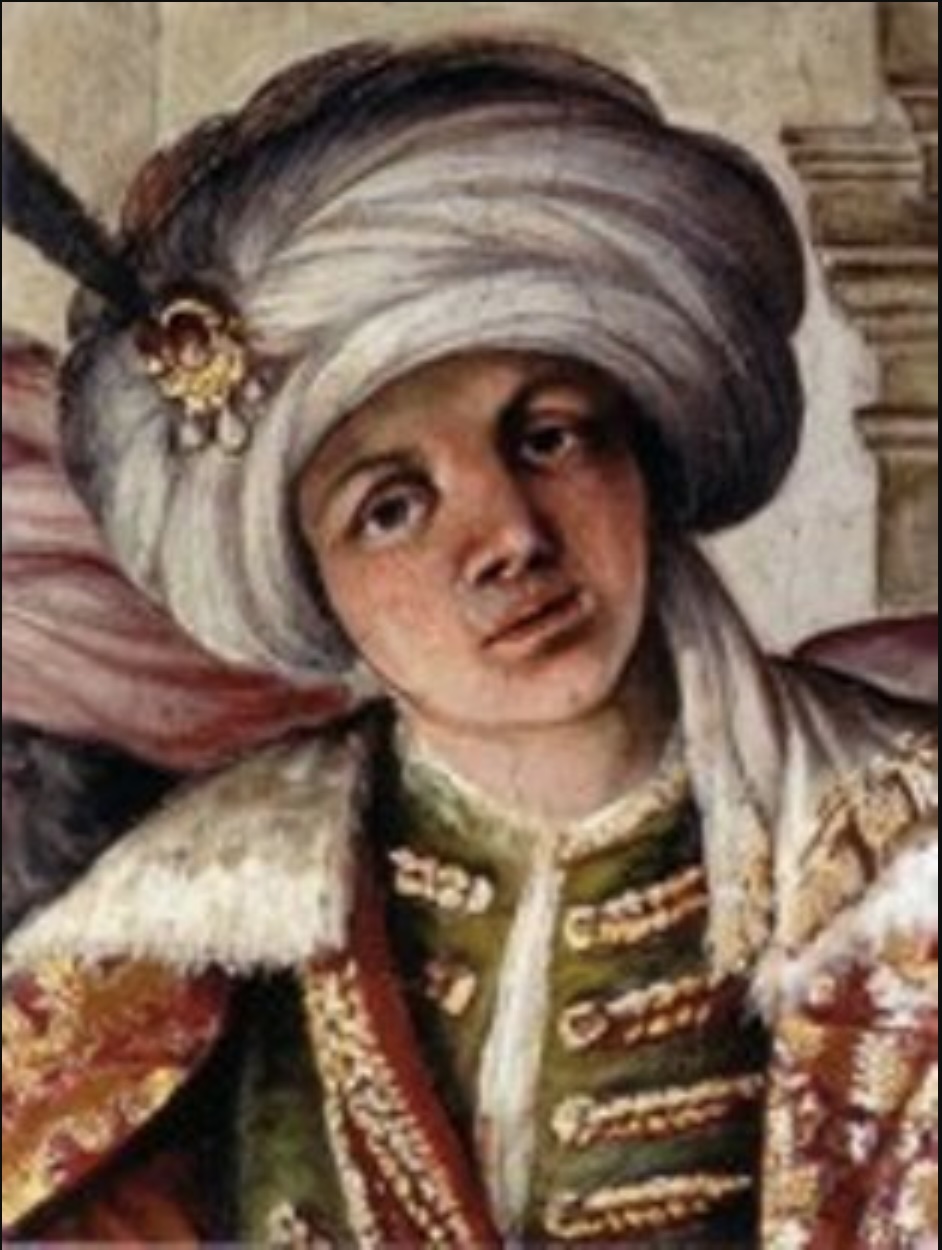

Husain Ali Beg, who accompanied Sir Anthony Sherley on the Persian embassy to Prague, where this likeness was made by the court artist, Aegidius Stadler.

Portrait of Shah Abbas I of Persia (1588-1629).

Unlike his grandfather, Tahmasp I, who expelled the Englishman Anthony Jenkinson from his court, upon learning he was a Christian, Shah Abbas’s policy was to enlist the support of the Europeans against their common enemy, the Turk. He claimed he ‘preferred the dust from the shoe soles of the lowest Christian to the highest Ottoman personage.’

To Spain he offered trading rights and the chance to preach Christianity in Iran in exchange for assistance against the Ottomans, but Spain, which had obtained possession of Ormuz from Portugal, would only cede it to Persia if the Shah agreed to sever relations with the East India Company, and this he was unwilling to do.

Eventually, Shah Abbas lost patience with Spain as well as with the Holy Roman Empire, which entered into a unilateral peace with the Ottomans, in 1606. From the English he obtained more: assistance in modernising his army and the support of the Company’s fleet, with which Ormuz was captured, in 1622.

Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (1576-1612), whose court Sir Anthony Sherley’s Persian embassy attended between November 1600 and February 1601, accumulating in the process debts of 46,000 thalers.

After his expulsion from Venice, in December 1604, Sherley returned to Prague, where Rudolph employed him to create a diversion against the Turks in North Africa. In October 1605, he arrived in Safi where, styling himself ‘ambassador’, he accumulated further significant debts through the lavish entertainment he offered to visiting Christian merchants. In 1606, he reached the court of Moulay Abou Fares, at Marrakesh, whom he unsuccessfully tried to involve in strikes against the Turks, in Algiers and Tunis. When he was dismissed from the court, in June, he was obliged to leave behind two of his company, as surety for his his debts of 250,000 florins.

Despite his poor track record, Sir Anthony was created count palatine by the emperor, on a brief visit to Prague, in 1607. Thereafter, he quit Rudolph’s service, and entered that of the King of Spain.

A double portrait of Sir Robert Sherley and his wife, Sampsonia.

Sampsonia was the daughter of a Circassian noble. The date of their marriage is not known exactly, but it must have occurred before 1607.

Robert wears the exotic Persian clothes which so impressed his hosts upon his return to Europe. She wears her native dress but holds a flintlock pistol and a pocket watch, to symbolise the technologies which Europe was introducing to Persia.

A detail from a painting of Sir Robert Sherley, from the time of his visit to Pope Paul V, in the Palazzo del Quirinale

Sherley presented the Pope with a letter from Shah Abbas asking him to induce the King of Spain to invade Cyprus, ‘an island abounding with provisions of all kinds, with ports most suitable for wintering his fleet, and near on hand for an attack later on Syria and … Aleppo, and so join up with the Persian army.’ Shah Abbas also asked the Pope to persuade the King of Poland, the emperor and the other European powers, to join a crusade against Turkey.

The Pope made Robert Count of the Sacred Palace of Lateran and bestowed upon him the right to grant certain indulgences, amongst them a power to legitimise bastards.

Portrait of Sir Robert Sherley, by Anthony Van Dyke

This portrait was painted, in 1622, when, after their extended stay in Madrid, the Sherleys revisited Rome, where Van Dyke was a young painter in the service of Cardinal Bentivoglio.

Of Sir Robert, Thomas Fuller wrote in his Worthies of England, ‘He much affected to appear in foreign vests; and, as if his clothes were his limbs, accounted himself never ready till he had something of the Persian habit about him.’

In this portrait, Sir Robert holds a Persian bow to go with his robes.

Gammeron or the City of Bandar Abbas in Persia, by Johannes Kip (1676).

Gombroon, opposite the island of Ormuz, became a Portuguese possession, in 1514. On it, they built the Comorao fort to protect the harbour on which they depended.

The fort was captured by Shah Abbas, in 1614. Immediately, he plotted the seizure of Ormuz, although this took him eight years to achieve.

In 1616, Shah Abbas sent Sir Robert Sherley to Spain, principally, it seems, to suggest to its rulers that they had nothing to fear from him. Sherley arrived at the end of 1617 , and spent four and a half futile years in Madrid. By the time he escaped, in 1622, Ormuz had been taken.

In 1623, Sherley appeared in London urging trade with Persia, but he was trusted little more there than he had been in Spain.

The city and fortress of Ormuz in the seventeenth century

With Goa (1510) and Malacca (1511), Ormuz (1515) was one of the strongpoints in the Indian Ocean secured for Portugal by Albuquerque. It was a Portuguese possession for a little over one hundred years, until it fell to Shah Abbas and an East India Company fleet, in 1622.

As England and Portugal were then at peace, the Company’s participation in the siege was a delicate matter, and it took a mixture of threats and promises of a share of the spoils for the shah to secure it. In the event, the Company obtained less than they expected, although their goods were passed free of Persian customs, and for a time they received part of the port’s income.

Lady Sherley, by Anthony van Dyck.

Before her final departure from England, in 1626, Lady Sherley petitioned the Privy Council on the treatment that her husband had received from the Persian envoy, Nuqd Ali Beg. She insisted that, when they returned to Persia, in the company of Sir Dodmore Cotton’s embassy, they should travel separately.

Taking into account ‘the Brutish disgrace done unto Counte Sherlye Ambassider from the Kinge of Pertia; unto this State, my Lord & husband, by the hand of that Barbarous Heathen who stileth himself Ambassodor, likewise from that Kinge,’ she required that ‘… a Mandamus may be directed unto the general and Captaynes of every Shipp, commanding them not to suffer the said two Ambassadors, to goe on shore, both at one tyme together, until they arrive by the devine pmission at Pertia; & that at every watering place wher men goe on Land to refresh themselves by the waye, my Lord maye have at least as much tyme allotted for himself as the other, who hath noe women amongst his Traine …’

A portrait of Nuqd Ali Beg in the British Library.

When Ali Beg, an ambassador from Shah Abbas, arrived in London, in 1626, he declared Sir Robert Sherley to be an imposter: at an interview organised by the Earl of Cleveland, they actually came to blows. Eventually, King Charles II decided that the two envoys should return to Persia to settle their dispute.

Upon his arrival at Surat, in November 1727, Ali Beg committed suicide, ‘not without cause,’ according to Thomas Herbert, ‘despairing of his Master’s favour and conscious to himself of his abusive carriage in England, both to Sir Robert Sherley and some other misdemeanors of his which begot a complaint against him to Shaw Abbas and made known by the way of Aleppo after his departure out of England.’

Herbert added that the shah was ‘at no time to be jeasted with in money matters or business relating to honour and reputation.’ He declared that, by taking his own life, Ali Beg had escaped the worse fate of being ‘hackt in pieces and then in the open market-place burnt with dogs’ turds.’

Sir Robert, however, was also disowned by Shah Abbas’s chief minister. He died just a few days after returning to Qasvin, in July 1628.

A portrait of Thomas Herbert , who accompanied Sir Dodmore Cotton on the embassy with which Ali Beg and Sir Robert Sherley returned to Persia, in 1627-1629. Herbert’s account of his journey in Some Yeares Travels into Africa & Asia the Great, Especially Describing the Famous Empires of Persia and Industant (1638) was judged by Lord Curzon to be the most amusing work on Persia ever published.

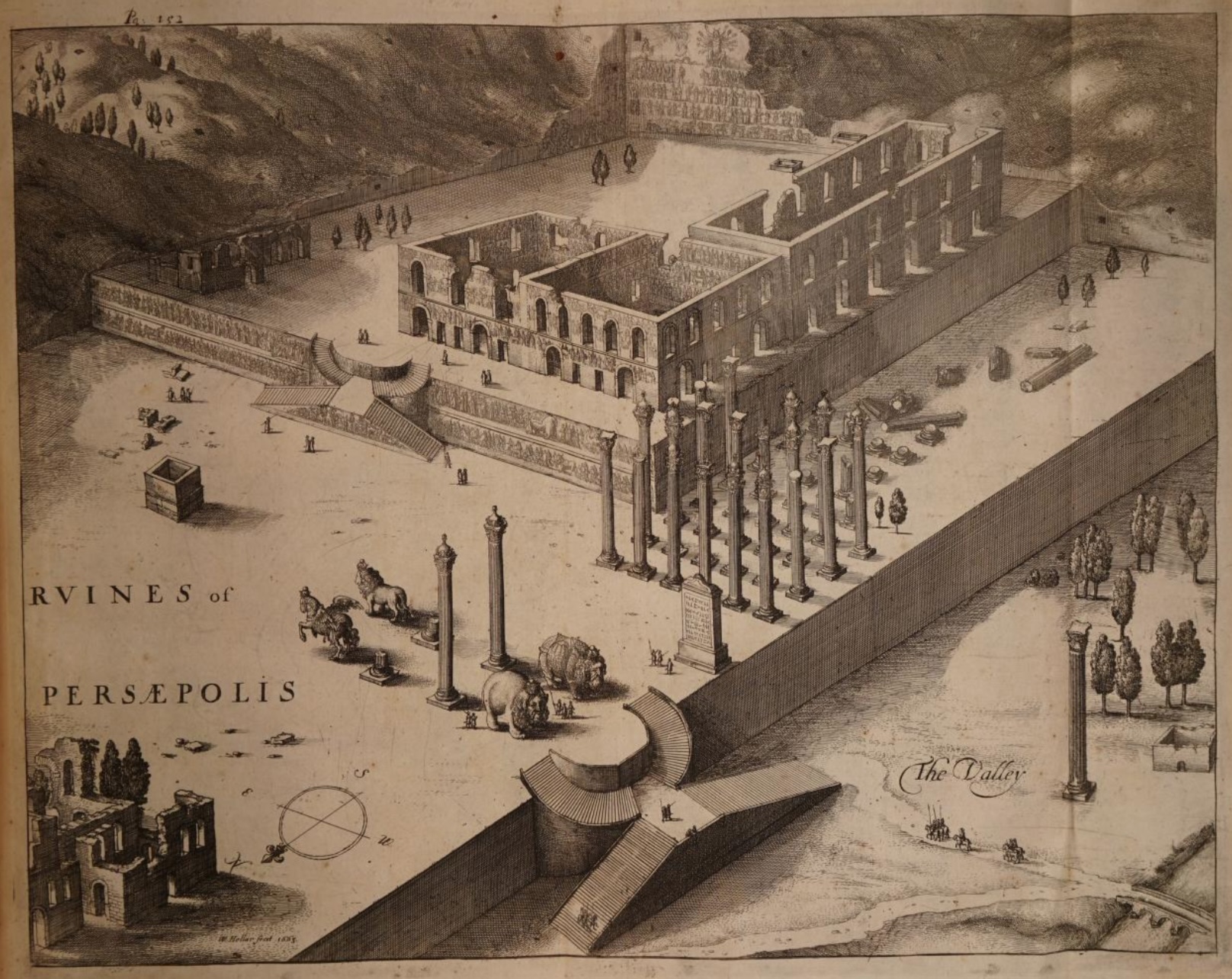

Plan of the ruins of Persepolis, from Thomas Herbert’s account of his travels in Persia.

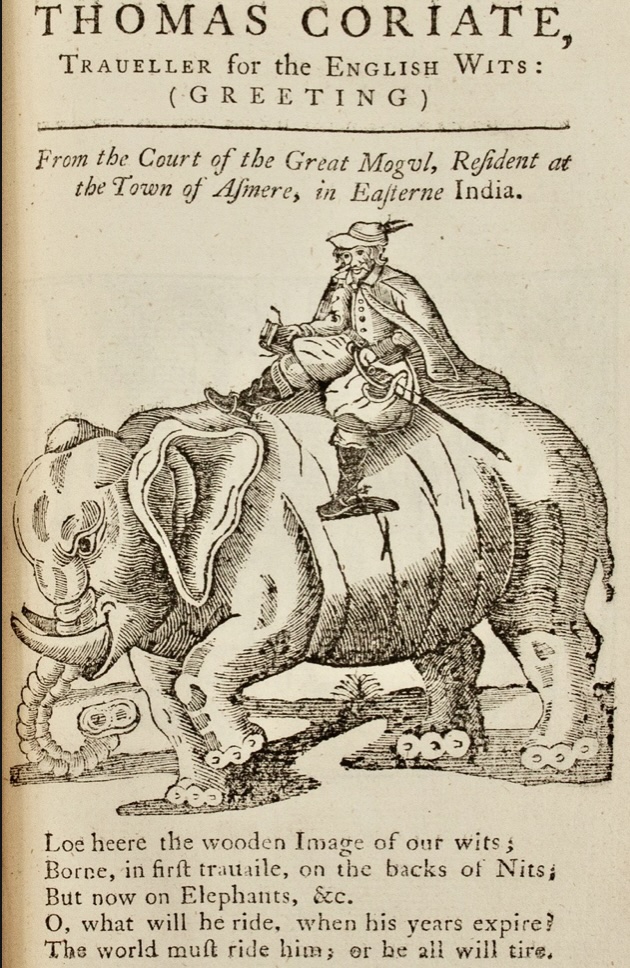

In his letter to Laurence Whitaker, Coryate wrote with pride of his having ridden upon an elephant, and of his ‘determining one day (by Gods leave) to have my picture expressed in my nexte booke’, showing him in the act. Although he did not live to see the book published, his ambition was realised, in 1616, when the publishers of this pamphlet of Coryate’s letters, remembered his wish.

Iron Ashokan pillar at the Qutub Minar in Delhi.

Of the pillars, William Finch wrote: ‘about 2c. without Dely, is the remainder of an auncient mole (mahal?) or hunting house, built by Sultan Berusa a great Indian monarch, with much curiositie of stoneworke. With and above the rest is to be seen a stone Pillar, which passing through three stories, is higher then all twenty foure foot, having at the top a globe, and a halfe moone over it. This stone, they say, stands as much under the earth, and is placed in the water, being all one entire stone; some say Naserdengady a Potan King would have taken it up, and was prohibited by multitude of scorpions, and that it hath inscriptions. In divers parts of India the like are to be seene, and of late was found buried in the ground about Fettipore a stone piller of an hundred cubits length, which the King commanded to bring to Agra, but was broken in the way, to his great griefe. It is remarkeable, that the quarries of India, specially neere Fettipore (whence they are carried farre) are of such nature, that they may be cleft like logges, and sawne like plancks to seele chambers, and cover houses of a great length and breadth. From this monument is said to bee a way under ground to Dely castle.’

Jahangir and Prince Khurram on his birthday, from a painting in the British Museum.

Working off Thomas Roe’s account of the ceremony in September 1616, William Foster calculated that Jahangir’s weight was 6,514 tolahs, equivalent to 12 stone 5lb. At today’s price of gold ($1,230/oz t), by donating his weight to the poor, the emperor would have given them $3.1 million (though, pace Coryate, Roe says they received silver.)

Of the ceremony, Terry wrote: ‘When I saw him in the balance, I thought on Belshazzar, who was found to light (wanting), Dan. 5,27. By his weight, of which his physicians yearly keep an exact amount, they presume to guess of the present estate of his body: of which they speak flatteringly, however they think it to be.’

Sir Thomas Roe (c.1581-1644).

Courtier to Elizabeth I, Henry, Prince of Wales, and his sister Elizabeth, explorer of the Amazon and Guiana (1610-11), Ambassador at the Mughal court (1615-18), and to Constantinople (1621-28), Roe also served on a mission to the Baltic (1629) in which he arranged the peace between Sweden and Poland which enabled Gustavus Adolphus to intervene in the Thirty Years War on the side of the Protestant German princes.

His last years were spent as a Member of Parliament trying, but failing, to help reconcile the opposing sides on the approach of the Civil War.

Roe was active in the affairs of the East India, Levant and Eastland Companies. In India, he saw the virtue of participating in the trade between Gujarat and Persia, but he was strongly of the view that it should be managed as a Company effort, and not left to amateurish merchants to organise.

After a journey of fifteen months, Thomas Coryate reached Ajmer, in July 1615. He wrote that he was received by William Edwards and the Company’s representatives ‘with verie loving respect.’ In September, he gave a ‘long, eloquent oration’ on the occasion of Sir Thomas Roe’s arrival. They had previously been acquainted through their connection at the court of Prince Henry, the son of James I, and, for a year, Roe permitted Coryate to live with him, in the Company’s compound.

Ajmer became part of the Mughal empire, in 1556, when it was captured by the emperor, Akbar. It remained an important city, for the Mughals used it as a military base in their campaigns against the Rajputs. It also enjoyed favour, for the dargah of Moinuddin Chisti, a thirteenth century Sufi saint and philosopher.

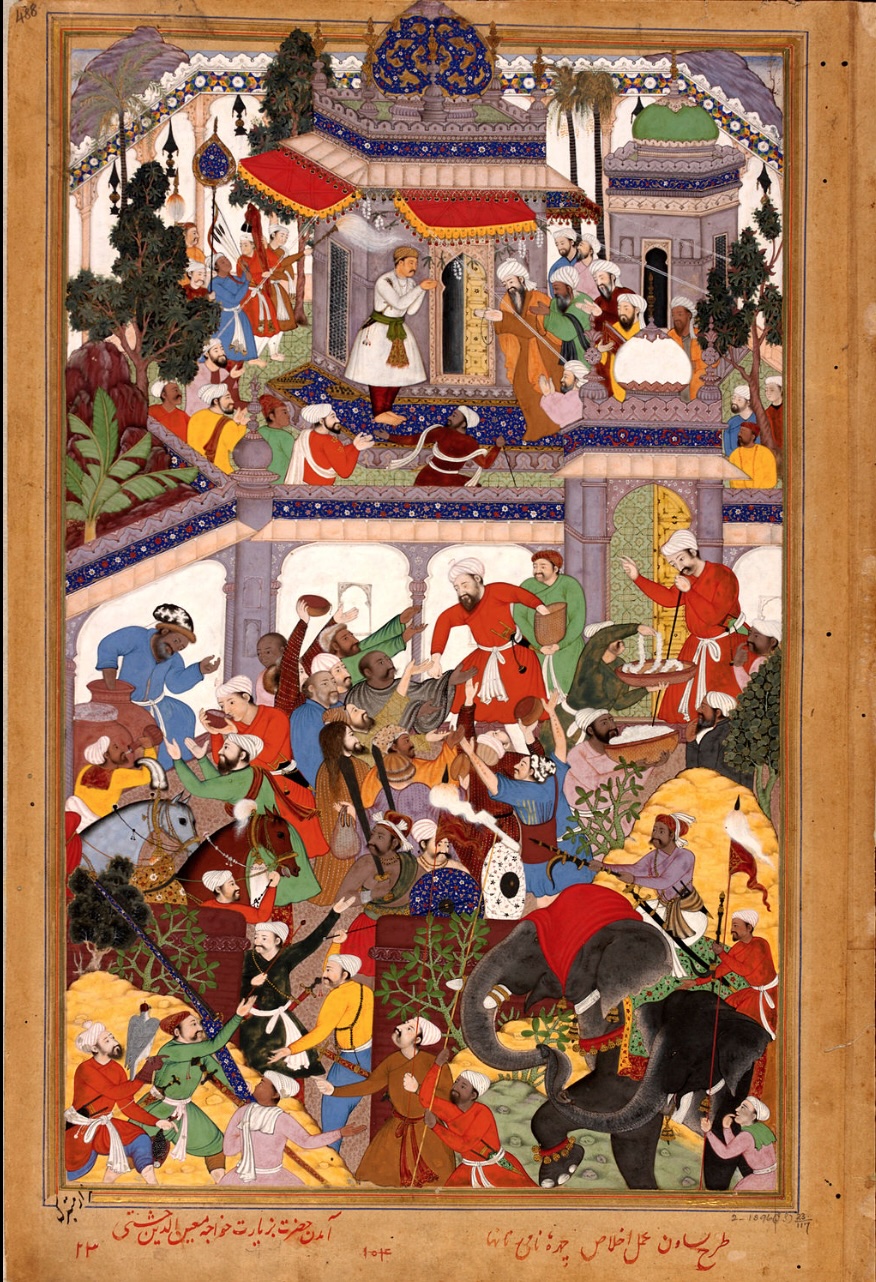

This sixteenth century painting, by Basawan, portrays Akbar visiting the saint’s shrine.

Jahangir in Darbar, by Abu’l Hasan (c.1620).

During his stay in India, Thomas Corayte used one of the three daily occasions at which Jahangir presented himself before his people to appear in the guise of a fakir, and address the emperor in Persian. He asked for a pass permitting him to travel to Samarkand, which was refused on safety grounds. However, Jahangir threw down to Coryate one hundred silver rupees, to go towards the expense of his journey home. When the news of this reached the ear of Sir Thomas Roe, he was greatly displeased, arguing that, by begging for money, Coryate had brought discredit on his nation.

An engraving of the water palace (Jahaz Mahal) at Mandu, from 1858.

Corayte joined Sir Thomas Roe here, towards the end of his stay in India. Roe had himself followed the imperial court: so huge was Jahangir’s entourage that it created a water shortage in the city. (Roe set up camp in a ruined mosque, beside which he was fortunate to discover a spring.)

Corayte found Sir Thomas in ill health, and his own formidable constitution became enfeebled also. Roe encouraged him to remain until he recovered, but Coryate decided to cross to the English factory at Surat, as a preliminary to returning home. He died there, in December 1617, after a journey of some three hundred miles, from the effects of dysentery.

In the letter to the Earl of Pembroke in which he wrote of the welcome distraction brought to his life at Ajmer by the company of Coryate, Thomas Roe mentioned ‘his exercise here or recreation is making or repeating orations, Principally of my Lady Hertford.’

This is the only suggestion we have that Coryate developed a passion for a lady. Since Lord Hertford, Frances’ second husband (her first, a wealthy wine merchant, died when she was in her twenties) was at one time Lord Lieutenant of Somerset and Wiltshire, it is certainly possible that they would have met in England. As Coryate’s biographer remarks, however, it is unlikely she would have regarded him with anything other than distant amusement. ‘She was,’ he writes, ‘very conscious of her noble ancestory – though Hertford used to temper her arrogance by tapping her cheek and saying “Frank! Frank! How long is it since you married the vintner?”’

After his suicide, Thomas Herbert reported that the body of the Persian ambassador, Nuqd Ali Beg, was conveyed ‘to Surat, where he was entombed ‘not a stone’s cast from Tom Corayte’s grave, known but by two small stones that speak his name, there resting till the resurrection.’ Later, in 1673, John Fryer reported that he was shown the ambassador’s tomb just outside the city’s Broach gate, ‘not far from whence, on a small hill on the left hand of the road, lies Tom Coriat, our English Fakir (as they name him), together with an Armenian Christian.’

Since then, the site of Coryate’s burial has been popularly associated with this domed memorial, near the Swally Hole. Although, for many years, the landmark was identified on Admiralty charts as ‘Tom Coryat’s Tomb’, there is no proof that at any stage it replaced the simpler memorial referred to by Herbert.

Roe Presents his Credentials to Jahangir. A rather fanciful mural by Sir William Rothenstein, in St Stephen’s Hall, the Palace of Westminster.

This is one of eight murals unveiled in 1927 by Stanley Baldwin, which were intended to epitomise the nation’s history from Alfred the Great to the Union with Scotland.

Beneath it, the inscription reads, ‘Sir Thomas Roe, Envoy from King James the First of England to the Moghul Emperor, succeeds by his courtesy and firmness at the court of Ajmir, in laying the foundation of British influence in India, 1614.’

Edward Terry’s stay in India happened by chance: he accepted an opportunity to serve as chaplain on Benjamin Joseph’s return voyage, in 1616, arrived after Roe’s chaplain had died and, at his request, agreed to replace him.

He joined Roe, in February 1617, stayed with him until Roe’s departure, in September 1618, and departed himself, in February 1619.

After his return to England, Terry appeared before the Court of Committees of the East India Company, asking to be released from paying freight on some calicoes he had brought home. He had, in fact, breached the regulations, but he was forgiven as Roe had commended his ‘sober, honest and civill life.’

He first presented his Voyage to East India to King Charles I, in 1622, and lived to witness the Restoration, which he celebrated in A Character of King Charles II. He died shortly afterwards, in October 1666, at the age of seventy.

The first British attempt to chart the Mughal empire was made by the Arctic explorer William Baffin, master’s mate on the Anne Royal, the ship on which Sir Thomas Roe returned to England, in 16i9.

Notable features include Jahangir’s dynastic seal in the top right-hand corner, the vast mountain range on India’s northern border, the cow’s head rock at Hardwar where the Ganges reaches India’s plains, and the avenue of trees between Lahore and Agra, which was remarked upon by Thomas Coryate.

William Baffin was killed at the siege of Ormuz, in 1622.

The suggestion that the mild-mannered English refrained out of respect for the prior claims of the Portuguese does not convince. In his patent to the men of Bristol, of December 1502, Henry VII made it clear that he recognised occupation only, and his patronage of John Cabot demonstrated he had little regard for the Pope’s gift of Tordesillas. This was an opinion with which the later Tudors concurred, as Elizabeth’s support for her Barbary and Guinea traders demonstrates. The reasons must be sought elsewhere.[1]

A lack of knowledge encouraged attempts to find a shorter, northern passage to the Orient, which fitted an expectation that demand for woollens would be stronger in colder climes. In 1527, Robert Thorne argued that the journey via the Pole was 2,489 leagues, compared with 6,000 leagues for the Spanish route via the Straits, and 4,300 leagues for the Portuguese one via the Cape. There was also a problem of shipping, for English coastal vessels – unlike the Portuguese – were too small to be economic, and it required the confidence born of experience to make them larger.[2]

For a while, when travelling eastwards, the English concentrated on the land route, via Moscow. Their effort followed Richard Chancellor’s success in obtaining freedom of trade from Ivan the Terrible, in 1553, and the formation of the Muscovy Company, two years later. Chancellor perished whilst returning from a second expedition, in November 1556, but, after he had escorted the Russian ambassador home, in 1557, Anthony Jenkinson obtained the tsar’s permission to continue down the Volga to the Caspian Sea and beyond. In December 1558, he got as far as Bokhara before deciding the effort was useless. (He departed in March 1559, just a few days before an army from Samarkand arrived.) [3]

Thereafter, Jenkinson directed the company’s attention to the province of Shirvan, near Baku, which he visited, in 1561-1562. Between 1564 and 1568, four expeditions were mounted, the last involving a vessel of seventy tons, which was commissioned to convey the company’s goods from Yaroslav, down the Volga, to Astrakhan. It ended in disaster when she was surrendered to pirates on the Caspian, in 1573. By 1579, Shirvan had been overrun by the Turks. The leader of a fifth expedition, Arthur Edwards, died at Astrakhan in 1580, and his associates, after being trapped in the Caspian ice, did well to escape death by starvation. Thereafter, English attention shifted southwards, to trade with the eastern Mediterranean.[4]

The exception was the expedition undertaken, for the Turkey Company, by John Newbery and Ralph Fitch, between 1583 and 1591. Newbery died somewhere between Agra and Aleppo, in 1584 or 1585, but Fitch made it all the way to Bengal, Burma and Malacca before returning to London. His report on long-range overland trade was far from encouraging. The Portuguese were hostile, the appetite in India for English woollens was limited, and its cotton and indigo could be bought competitively in Syria and Egypt. The Levant Company, formed in 1592 from the merger of the Turkey and Venice Companies, therefore abandoned it, although to protect its interest, it took care to obtain a trading monopoly on the route through the Turkish dominions ‘into and from the East India.’[5]

By a process of elimination, the English were being driven towards the sea route, yet a crucial problem remained: a shortage of capital. The exploits of James Lancaster (1591) and Benjamin Wood (1596) convincingly demonstrated that the risks of the journey via the Cape were too great to be borne by just a few. This problem was overcome with the structure of the East India Company’s first stock, which enabled the risks to be shared with others. Thereafter, the Portuguese did what they could to deprive the newcomers of the bases they needed but, after the victories of Thomas Best and Nicholas Downton, and the embassy of Sir Thomas Roe, England’s sea route to India became established.

Interest in the landward route quietly withered. Yet, in succeeding years, there were some who, from various motives, followed the path trodden by Newbery and Fitch. Most extraordinary of them, perhaps, is Thomas Coryate. He might claim to be England’s first professional travel writer. His story will serve as the anchor to what follows.

Thomas Corayte in Europe and the Levant

Coryate was born at Odcombe, near Yeovil, in Somerset, in around 1577. After a spell at Gloucester Hall (Worcester College), Oxford, he was introduced to the court of King James, probably through the family of his godfather Thomas Phelips, the builders of Montacute House. Like Phelips’ son Robert, Coryate was engaged in the household of the young Prince Henry, where, if the comment of Thomas Fuller is to be trusted, he served as an unofficial court jester:

Sweetmeats and Coryate made up the last course at all court entertainments. Indeed, he was the courtiers’ anvil to try their wits upon; and sometimes this anvil returned the hammers as hard knocks as it received, his bluntness repaying their abusiveness.

Fuller wrote that Coryate carried folly in his very face, the shape of his head being ‘like a sugar-loaf inverted, with the little end before, as being composed of fancy and memory, without any common sense.’ Coryate was assuredly no fool, but these words need not have caused offence, for he craved the limelight and, to secure it, he almost cultivated a reputation for oddity. Not for nothing did he called himself ‘Odcombian’. ‘Come forth thou bonnie bouncing booke then, daughter / Of Tom of Odcombe that odde Joviall Author’ wrote Ben Johnson in the character sketch that prefaces Coryate’s opus, the Crudities.[6]

King James was frustrated that Prince Henry did not study more seriously, that he spent much of his time charging about on horseback with pistols ‘after the manner of the wars’, and discussing, with ‘great captains’, the furniture of battle, ambuscades, scalings and fortifications. He was delighted by a twenty-five-foot model warship, built for him by the shipwright, Phineas Pett, which he named Disdain. Worst of all, Henry befriended James’s bête noire, Sir Walter Raleigh, then a prisoner in the Tower. ‘None but my father would keep such a bird in a cage,’ Henry was reputed to have said. Perhaps it was interaction with characters like Sir Walter that fired Coryate with a taste for the exotic. Yet, he was of scholarly bent, uninterested in utilising a naval career to see the world. Equally, the purse of a rector’s son was of a certain size only. He resolved, therefore, to proceed alone, at his own pace, to those places where his interests most inclined him to go.[7]

In the spring of 1608, Coryate fixed on Venice, by way of France and Italy. The first paragraph of his account brings to the fore his ebullient character, and his self-mockery:

I Was imbarked at Dover, about tenne of the clocke in the morning, the fourteenth of may, being Saturday and Whitsun-eve, Anno 1608, and arrived in Calais (which Caesar calleth Ictius portus …) about five of the clocke in the afternoon, after I had varnished the exterior parts of the ship with the excrementall ebullitions of my tumultuous stomach, as desiring to satiate the gormandizing paunches of the hungry Haddocks … with that wherewith I had superfluously stuffed my selfe at land, having made my rumbling belly their capacious aumbric.[8]

Coryate estimates that he journeyed 1,975 miles. The coaches in France were more comfortable than England’s carts, yet he eschewed them. Instead, he walked, rode, or travelled by river. His account, Coryat’s Crudities, is very much what it says on the label: a collection of raw impressions, a mixture of anecdote, observation, ribaldry, and social commentary. He was impressed by how much stone had gone into the building of Paris, by the cathedral at Amiens (but not by Notre Dame), by the industriousness of the Milanese, and by most things in Venice, except the ‘seducing and tempting Gondoleers of the Rialto bridge’ and the ‘chapineys’ (chopines) worn by the ladies to keep their clothes out of the mud.

This was, of course, a time of unusual religious sensitivity, and Coryate’s convictions reflected the age. Visiting the Venetian ghetto, he took it into his head to convert a Rabbi, persisting until ‘he seemed to be somewhat exasperated against me,’ and a crowd of forty or fifty others became involved. By good fortune, the English ambassador happened to pass, and he sent his secretary to the rescue before any blood was spilt.

Coryate was the protestant son of a protestant country parson, so this was not a unique event. In Lyons, he had an acrimonious argument with a Turkish Muslim who was accompanying the French ambassador from Constantinople. In Calais, he showed himself not a whit sympathetic to the Catholics’ ‘mutilated sacrament’. He insisted that it defrauded the lay people of the wine to which they were entitled, according to ‘the holy institution of Christ and his Apostles, and the ancient practice of the Primitive Church.’ Even so, whilst, at Notre Dame, he deprecated ‘a very long and tedious devotion,’ he had the honesty to praise the singing and the person of the bishop, ‘a proper and comly man as any I saw in all the city.’

Thomas cultivates a scholarly demeanour, and, in the Crudities, he is not shy to put his classical knowledge on display. He details the grandeur of the amphitheatre at Verona, he deplores the use of the figures of the ungodly Julius Caesar and Trajan on the façade of Bergamo’s cathedral, and he delights us with an encounter with a wood-cleaver on the road to Metz, who was able to speak Latin:

He was both learned and unlearned. Learned because being but a wood-cleaver … he was able to speake Latine. A matter as rare in one of that sordid facultie as to see a white Crowe or a black Swanne. Againe he was unlearned, because the Latin which he did speak was such incongruall and disjointed stuffe …

All of this, and more, is reported in detail, and with humour, in Coryate’s prototype travelogue, a copy of which – likened to a newly laid egg – he presented to Prince Henry, in March 1611:

I wish [he wrote] by the auspicious obumbration of your Princely wings, this senseless Shell may prove a lively Birde … and so breede more Birds of the same feather that may in future time bee presented as novelties unto your heroycall protection.

Soon, Coryate was ready for a second journey. In October 1612, he left for Constantinople, travelling via the Venetian Isle of Zante (famous for its currants), then Chios and the Troad. There he declaimed, at length, to his fellows on the tomb and palace of Priam, which he thought they were contemplating. Inspired by the occasion, and to the concern of the Turks nearby, who feared a beheading, one of the party, Robert Rugge, drew his sword, ceremoniously knighted his companion, and begged an extempore oration:

Coryate no more, but now a Knight of Troy,

Odcombe no more, but henceforth England’s joy.

Brave Brute of our best English wits commended;

True Trojane from Aeneas race descended.

Rise top of wit, the honour of our Nation,

And to old Ilium make a new Oration.

Needless to say, Coryate obliged. [9]

In Constantinople, Coryate stayed at the residence of the English ambassador, Sir Paul Pindar. To do so was standard practice but, by now, Thomas was something of a celebrity: he remained for some ten months, writing up his notes, which were sent home and later distilled by Purchas. In a letter he wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton, in April 1613, Sir Paul indicated that, this done, Coryate’s plan was to travel to Jerusalem and Cairo before returning to the Veneto. Evidently, the idea of journeying to India occurred only later.[10]

He travelled via Mytilene (‘the people flocked about us, many of them women, the ugliest sluts that I ever saw, saving the Armenian trulls of Constantinople’), then to Aleppo and Damascus. Unfortunately, at that point, Purchas broke off his narrative, remarking, ‘wee have travelled with so many Travellers to Damascus and thence to Jerusalem … that I dare not to obtrude Master Coryats prolixitie on the patientest Reader.’

Edward Terry, author of A Voyage to East-India, whom Coryate met in India and on whom for now we have partly to depend, tells us that, in Jerusalem, Coryate had a cross tattooed on his wrist ‘to continue with him so long as his flesh should be covered with skin’ and that, from there, in the company of another Englishman, Henry Allard, he travelled back to Aleppo via the Dead Sea, the River Jordan, and Mount Lebanon. There they parted, Allard bound for England, Coryate for India.[11]

Quite what animated Coryate with the idea of his ‘Great Walk’ is not immediately clear. Perhaps he had learned of Anthony Jenkinson and Ralph Fitch, whose journeys had been reported by Hakluyt. Perhaps Paul Pindar mentioned to him the journey, from India to Aleppo, of Robert Coverte and Richard Martin, survivors of the wreck of the ship Ascension, which hit the rocks on the Surat Coast, in August 1609. As Aleppo’s consul, Pindar had provided them with food and lodging when, ‘destitute of both mony and cloaths,’ they reached it, after a journey of fourteen months, via Kandahar, Isfahan, and Baghdad. The best candidate, perhaps, is someone mentioned by John Cartwright in The Preacher’s Travels. This was published in 1611, shortly before Coryate’s departure from Odcombe. Later, John Mildenhall’s extraordinary adventures caught the attention of Samuel Purchas. If Coryate was put in mind to add to his reputation as a legstretcher, possibly the exploits of Mildenhall provided the inspiration.[12]

The Exploits of John Mildenhall

Of the early career of John Mildenhall little is known, other than that he was a trader in the Levant: references in his correspondence and in the East India Company’s Court Minutes connect him to Richard Staper, one of the founders of the Turkey Company. We know he was in Constantinople in 1598, as ‘John Midnall (cuckold)’ is mentioned by John Sanderson as one of those who, alongside Paul Pindar, John Garraway (‘marchaunt’), Edward Barlie (‘enviouse makbate’), David Bourne (‘trecherouse foole’), William Pate (‘politique palterer’), Charles Merrell (‘Puritan whoremonger’), William Harris (‘simple felowe’) and Sampson Neweport (‘Papist mellowe’), helped to appraise and sell the effects of the ambassador, Edward Barton, who had died of dysentery in February.[13]

Cuckold? In a letter, dated 12 March 1600, John Sanderson referred to William Birkhead, who ‘hath ben somewhat wild in times past, but now he wilbe tamer.’ He was, he says, ‘nether so bad or madd as som would make him,’ but the ambassador had his feet bastinadoed because he called Mildenhall a cuckold with insufficient reason. Since Mildenhall himself tells us he began his journey to India from London, he must have travelled home beforehand. Perhaps he did so to establish the truth in Birkhead’s charge; if so, it may have been to escape domestic unhappiness that he returned to the East.[14]

Mildenhall departed London in February 1599, on the Hector, of which Richard Parsons was master. This was the vessel which carried the organ commissioned by Queen Elizabeth from Thomas Dallam, as a gift for Sultan Mehmet III. Mildenhall travelled in a private capacity, however, as his choice of language at the beginning of his account (‘I … tooke upon me a Voyage from London towards the East-Indies’) indicates. He quit the Hector at Zante, and travelled independently to Constantinople, where he says that he ‘staied about my Merchandize’ until May 1600.[15]

Mildenhall considered travelling to Cairo but, in the end, he departed for India from Aleppo. Rumours of the formation of the East India Company had reached Constantinople in 1599 and it is possible that he sought to obtain a grant of privileges for it, knowing his reward for doing so should more than compensate the effort. As we shall see, Mildenhall was nothing if not an opportunist.[16]

It was in Aleppo that he met John Cartwright. They departed from there, on 7 July 1600, in a caravan of six hundred, comprising a mixture of Armenians, Persians, Turks, and others. Taking a somewhat circuitous route, they crossed the Euphrates at Bir, passed the battlefield of Carrhae, near Urfa (Edessa), skirted the shore of Lake Van (‘in compasse nine dayes journey about, which I myselfe have rowed round about’) and made for Julfa, on the border between modern Iran and Azerbaijan. According to Cartwright, they then made a detour to Jenkinson’s Shirvan. He refers to a turret made of stone and flints in which the conquering Persians placed the heads of the country’s nobility, ‘for the greater terror of the people,’ and also the remains of a wall built by Alexander the Great between Derbent and Tiflis. Of these Mildenhall makes no mention but, if he had been investigating the Russian trade with Persia – and Cartwright alludes to the English factory at Shemakha – he may have seen fit not to broadcast that he had been infringing on the prerogative of the Muscovy Company.

From Shirvan, the pair journeyed to Tiflis and Qazvin, where they remained for a month. They then travelled to Qom and Kashan, where they separated – Cartwright continuing to Isfahan, and Mildenhall to Yezd, Kerman, Sistan, Kandahar and Lahore, a distance of about two thousand miles.[17]

In a letter from Qasvin, dated 3 October 1606, Mildenhall told Richard Staper that he reached Lahore in 1603. He does not give the month. Robert Coverte was told by the Jesuit, Jerome Xavier, that he had stayed in Agra for three years. This may be an overestimate, however, as Emperor Akbar died in October 1605, which Mildenhall does not mention, as he might be expected to have done, if he had been present. Whatever, it is clear that his stay was an extended one. A letter sent by Xavier from Agra, in September 1604, refers to the arrival of ‘an English heretic’, undoubtedly Mildenhall, who, he says, ‘tried by means of heavy bribes’, for two years, to obtain a firman giving the English access to the Mughal’s ports. That Mildenhall claimed to have come to ‘treat of such businesse as I had to doe with him from my Prince’ we should put down to grandstanding. There is no more evidence to support this assertion than there is to suggest that, as a trader in the Levant, he had been acting in anything other than a private capacity. Even so, his initial reception was positive. The sticking point which emerged was that, alongside the trading rights that had been granted to the Portuguese, he wished for something extra. In short, that

… because there have beene long Warres betweene her Majestie and the King of Portugall, that if any of their ships or Portes were taken by our Nation, that he (Akbar) would not take it in evill part, but suffer us to enjoy them to the use of our Queenes Majestie.

Akbar was bound to be circumspect about granting as much. For his part, Mildenhall says the intervention of the Portuguese stayed the emperor’s hand: that four Jesuit priests (‘whereas before wee were friends, now we grew to be exceeding great Enemies’) complained to Akbar that the English ‘were all Theeves and that I was a Spye’; that, once given leave, they would seize some of his ports ‘and so put his Majestie to much trouble.’ He charged the Jesuits with dishing out bribes to Akbar’s senior counsellors ‘that they should not in any wise consent to these demands of mine.’ In response, Xavier accused Mildenhall, ‘like a snake in the grass’, of siding with some of his disaffected countrymen, who issued slanders about the Jesuits and prejudiced the emperor against the Portuguese.[18]

The arguments rumbled on and Mildenhall’s situation became desperate. The Jesuits lured away an Armenian whom, for four years, he had had employed as an assistant, leaving him ‘in these remote Countries without Friends, Money, and an Interpreter.’ Mildenhall, however, was nothing if not determined. For six months, he says, he studied Persian with the help of a local schoolmaster. Once equipped, he presented to His Majesty ‘the great abuses of these Jesuites in this his Court,’ and defeated them with the saucy argument that, if his requests were granted, the English would send ambassadors, who would serve as pledges for their countrymen’s good behaviour. He added, that, since ambassadors were changed every three years, they would provide a font of ‘great and princely presents’, of which the Jesuits ‘by their craftie practices’ were seeking only to deprive him:

Upon these and other such like speeches of mine, The King turned to his Nobles and said, That all that I had said was reason; and so they all answered. After this I demanded of the Jesuites before the King; In these twelve yeeres space that you have served the King, how many Ambassadours, and how many presents have you procured to the benefit of his Majestie: With that the Kings eldest sonne stood out, and said unto them, naming them, That it was most true, that in eleven or twelve years, not one came, either upon Ambassage, or upon any other profit unto his Majestie. Hereupon the King was very merrie, and laughed at the Jesuites, not having one word to answer.[19]

Mildenhall, we are told, obtained sealed documents confirming the privileges he craved ‘without any more delay or question.’ Armed with these, and a present of ‘Garments … of the Christian fashion very rich and good,’ he started for home. Initially, he aimed for Baghdad but, in the letter from Qazvin, he wrote to say that some Italian merchants had learned of his success and were plotting him harm. As a result, he decided to return via Moscow, departing within four months. The pace he set was leisurely: as late as 21 June 1608, two and a half years later, he had still not reached England. On that day, his letters to Richard Staper were read to the Company’s Directors. They detailed the privileges he had obtained, which he offered for a payment of £1,500. The Directors chose to wait before committing themselves.[20]

When he made his petition in person, in May 1609, Mildenhall had been away for more than a decade. He had lingered too long. More than two years before, the Company had sent William Hawkins with letters for the emperor from King James. They preferred to wait on the results of his voyage. In disgust, Mildenhall appealed to the king, arguing that, given his expenditure of time and treasure, he should be permitted to capitalise on Akbar’s grant in a personal capacity. After some debate, this idea was rejected. In October, perhaps by way of compensation, the Company suggested a post as a factor, but terms could not be agreed and, in the end, the offer was rescinded, Mildenhall being judged ‘not fit to be engaged’.[21]

The next mention of Mildenhall is in a letter from Sir Thomas Glover, Pindar’s predecessor as ambassador in Constantinople, who says that he tried, in 1610, to open a trade route to Persia via the Black Sea. The effort failed when some ‘secret enemies’ accused him of spying. The charge was groundless, but he was hauled back to the Turkish capital, and it was only through Glover’s intervention that he was cleared and, after ‘extreame bickeringe of words and blatteringes,’ his confiscated goods were returned to him.[22]

Undeterred, Mildenhall attempted a final thrust. In April 1611, he departed Aleppo for Persia with stock belonging to Richard Staper and some other merchants. With the passage of time, a suspicion arose that he planned to embezzle the goods and divert them to India. Richard Steele and Richard Newman were sent in pursuit. They caught up with Mildenhall at Tombaz, near the border, and conveyed him to Isfahan. There he was obliged to disgorge the goods and nine thousand dollars in cash, which Newman took with him back to Aleppo. Mildenhall continued to India, accompanied by Richard Steele.[23]

In Steele, Mildenhall had stumbled upon someone who was just as much the opportunist. How they got on is an interesting topic for speculation, but speculation it must remain. In Lahore, Mildenhall fell sick. Steele continued to Ajmer alone, Mildenhall following in his wake. He arrived in April 1614 but, two months later, he died. Sadly, ‘the long paper book he used daily to write in’ was immediately burnt.[24]

Samuel Purchas doesn’t give Mildenhall much of a commendation. Repeating an assertion relayed by Nicholas Withington, he declared him to have been an ‘English Papist’ who,

… had learned (it is reported) the Art of poysoning; by which he made away three other English men in Persia, to make himself Master of the whole stock; but I know not by what meanes himselfe tasted of the same cup, and was exceedingly swelled, but continued his life many moneths with Antidotes.[25]

That Mildenhall was a Catholic we may take to be true: he was buried in the Catholic cemetery in Agra, where his tombstone still stands. That he was a poisoner, there is good reason to doubt.

By the terms of his will, Mildenhall left his estate to two children whom he had left behind in Persia. The Frenchman, ‘Augustin’, in whose house Mildenhall was staying at his death, undertook to serve as his executor, and to marry his daughter and bring up his son. However, he became involved in a lengthy battle with Thomas Kerridge, who was sent to Agra to claim the assets which the Company said were still owing to Mildenhall’s employers. Nicholas Downton states that the Surat factors were encouraged in their endeavour by the chancer, Steele. In truth, their case was weakened by the fact that Augustin had witnessed the settlement involving Richard Newman at Isfahan. Naturally enough, he was supported by the Jesuits and, since Kerridge was able to produce no written authority to support his claim, he had to resort to bribes to get his way. For a while, the emperor, deciding neither side ‘had sufficient right thereto’, sequestered the assets to himself. In the end, Kerridge obtained most of what he sought, but it was a was an unfortunate squabble with which to end a life.[26]

Despite that, Mildenhall’s achievements should not be underestimated. He was the first Englishman to reach India overland from Aleppo (Steele was the second), and he completed the trek twice, with a return journey to boot. As it happens, despite his pretence that he represented his queen at Akbar’s court, he seems to have made a convincing case. Jahangir was witness to the assertion, and it is possible that, in 1608, he welcomed William Hawkins because he believed him to be the ambassador whom Mildenhall promised would follow.

An Introduction to the Sherleys

Whether or not it was, in fact, he who provided Coryate with the idea of walking from Aleppo to India, this is what, in September 1611, he decided to do. Departing with a caravan, he followed a route similar to Mildenhall’s, over the Euphrates to Urfah (which he confused with Ur), to the crossing of the Tigris at Diyarbakir (‘Diarbekr’).

Here, he was robbed of most of his money by a Turkish horse guard, ‘but not all, by reason of certaine clandestine corners where it was placed.’ It was a blow, especially as, a little later, he ‘was cousened of no less than ten shillings sterling by certaine lewd Christians of the Armenian nation.’ Coryate claims that he frequently lived on as little as a penny a day, so ten shillings might have paid for several months’ rations: in the ten months he took to travel to the Mughal’s court, he spent on himself just £2,10s. In more senses than one, he was history’s first backpacker.

After the crossing of the Tigris which, in the dry season, he says ‘reached no higher then the calfe of my legge,’ Coryate’s route took him through Armenia, to Tabriz, Qazvin and Isfahan. These presented a study in contrasts, the former much ruined by the wars between Persia and Turkey, the last ‘the metropolitan citty of Persia’, where the shah kept his court in peace and the caravans collected for the onward journey to India. At Isfahan, he stopped for two months hoping for, but not obtaining, sight of Shah Abbas. Coryate was troubled to learn that he was away in Georgia (‘Gurgistan’) ‘ransacking the poor Christians ther with great hostility, with fire and sword.’[27]

The journey to ‘the goodly city of Lahore’ took four months. Coryate travelled in a caravan comprising six thousand people, two thousand camels and 1,500 horses. Of the road, he leaves little record, although he does mention one rather surprising encounter:

About the middle of the way, betwixt Spahan and Lahore, just about the frontiers of Persia and India, I met Sir Robert Sherley and his lady, travailing from the court of the Mogul (where they had beene verie graciously received, and enriched with presents of great value) to the King of Persia’s court; so gallantly furnished with all the necessaries for their travailes that it was a great comfort unto me to see them in such a florishing estate.

The gifts which the Sherleys took with them included two elephants and eight antelopes, but Coryate was especially delighted when they produced from their luggage a copy of his Crudities ‘neatly kept’. This they promised to introduce to the shah, to aid Coryate’s chance of obtaining an audience during his return journey. Thomas concludes,

Both he and his lady used me with singular respect, especially his lady, who bestowed forty shillings upon me in Persian mony; and they seemed to exult for joy to see mee, having promised me to bring mee in good grace with the Persian King, and that they will induce him to bestow some princely benefit upon me. This I hope will be partly occasioned by my booke, for he is such a jocond prince that he will not be meanlie delighted with divers of my facetious hieroglyphicks, if they are truelie and genuinely expounded unto him. [28]

Just as Sir Robert Sherley knew of Coryate, so it is possible that Coryate already knew of Sir Robert, as he had been introduced to the English public in Anthony Nixon’s Three English Brothers, of 1607. He was the youngest of the three sons of Sir Thomas Sherley of Wiston, who served as High Sherriff of Sussex and MP for Steyning. It is time to give an account of their extraordinary adventures.

Sir Thomas was properly representative of the squires of the age in that he was extravagant with his money, and frequently indigent. In the late 1580s, an opportunity for sequestering badly needed funds arose with the Earl of Leicester’s expedition to the Low Countries. As Treasurer at War, Sherley claimed that he received emoluments of £700, or less, a year. Yet, in April 1589, Leicester’s successor, Lord Willoughby, calculated that, by drawing pay for more men than were serving, or underpaying them, or buying in their debts at a trifle, and the like, he was earning £20,000, nearly a fifth of the total annual cost of the army. His undoing came in that year, when he contracted with a London merchant, William Beecher, for the supply of materials to military expeditions in Portugal and France. Unfortunately, he did so on a fixed cost basis and, although he allowed for a comfortable margin, he did not allow enough. In 1596, Beecher went bankrupt claiming that Sir Thomas had withheld from him £43,000 of the Queen’s money. There ensued a series of arguments over his cryptic bookkeeping, which ended in Sir Thomas being sent to the Fleet Prison. Released in 1598, he lived a precarious existence until his death, in December 1612.[29]

Sir Thomas’s eldest son, Thomas the Younger, had an unsuccessful career as a privateer before he was captured and imprisoned by the Turks, in 1603. He was again imprisoned, twice, in England: once for seeking to ‘batter’ the operations of the Levant Company (two years in a Constantinople jail had convinced him that it should having nothing to do with the Ottomans), once as an insolvent debtor. Shortly before his father’s death, he took poison, but failed to take his life. Afterwards, he inherited his father’s liabilities, but obtained immunity from prison by serving as an MP. In 1622, he sold Wiston and retired to the Isle of Wight, where, according to Sir John Oglander, he married a whore, spent all, and came to a miserable end, in 1633.[30]

Sir Anthony Sherley’s Mission to Persia

Thus, in brief, the credentials of the elder Sherleys. Robert’s fortunes mostly entwined with those of his second brother, Anthony.

In 1596, he obtained the support of his father and the Earl of Essex, for a voyage to capture São Thomé, off Equatorial Guinea. The project was a financial disaster: Burghley reported that Anthony returned ‘alive but poor’. It cost Thomas the Elder nearly £20,000. Anthony retained the support of the Earl, whose first cousin, Francis Vernon, he had married, but he was honour-bound to effect something to restore the family’s finances.[31]

An opportunity arose, in 1598, when a plan to fan a contest between Ferrara and the Pope into a conflagration involving France and Spain flopped, and Anthony found himself in Venice with £8,000 of the Earl’s money. He developed the idea of journeying to the Red Sea ‘to influence the King of Persia to break with Spain.’ Later, in 1613, Anthony claimed that the scheme had been proposed by the Earl himself, with the twin objectives of supporting the protestant religion, and trade. That, however, was some time after the event (and Essex’s execution). It may have been his own initiative. In 1598, Anthony knew that John Davis had been sent by the Earl to assess Portugal’s establishments in the Indies, under Cornelis de Houtman. In applying for a travel pass through Turkey, he stated that his purpose was to meet with the Dutch fleet in the Red Sea. The encouragement of the Venetians, who were keen to break the growing grip of the Portuguese over trade with Persia, from Ormuz, catalysed the scheme.[32]

Later, during a stopover at Aleppo, Anthony explained his plan to the factors of the Levant Company. They had a similar interest to the Venetians in the overland trade, so they accorded their support also, including ‘large meanes and letters of favour and credit to the company of Merchants.’[33]

In his Relation, however, Anthony admits to keeping some of his motivations close to his chest. There were, he concedes, ‘some more private designes’ behind the scheme, ‘which my fortune … counselleth mee not to speake of.’ Not everyone was convinced that his motives were honest. In December 1598, John Chamberlain informed Dudley Carleton,

Sir Ant. Shirley has wrung £400. from our merchants at Constantinople, and has scraped together £500. more at Aleppo, with which he has charged Lord Essex by his bills, and is gone away to seek his fortune.[34]

Certainly, during his audience with Shah Abbas in Isfahan, Anthony’s idea went through a not-so-subtle change. He learned that the shah had recently defeated his enemies, the Uzbeks, and that he was ready to recover his Western provinces. What better way of achieving this was there, than by forming a Perso-Christian alliance against the Turk? The plan of linking with the Dutch in an attack on Ormuz – the concept proposed by the Venetians, seconded by the Levant factors, and for which the Turks had granted his pass – was dropped and another adopted which would do more than any other to disrupt the overland trade on which Turkey, Venice and the Levant Company depended.[35]

It is true that Sherley told the shah it would help his cause if he granted the Europeans freedom to trade in his kingdom, but this is mentioned at the end of his account, almost as an afterthought:

… a greater meanes your Majestie may worke by: in giving … securitie of Trade, goods and person to Christians, by which you shall bind their Princes, expresse the charitie of your Law, serve your selfe in divers thinges of them which have beene hidden unto you, both for your utilitie, strength and pleasure.[36]

Later, in a letter sent from Moscow, he referred to a plot whereby Don Manuel, the son of the Prior of Crato (pretender to the throne of Portugal), would be sent to India to join with the Mughal Emperor and a hoped-for eight thousand disaffected Portuguese, and seize Portugal’s possessions:

The king of Tabur (Lahore) is the mightiest king of the Indies, with hym I have so well fytted my credytt, that I have receaved two messages from hym, in one he hathe desyred of me, some man which knowes the warres to dyscyplyne his men … and uppon his commng unto hym he will make warr uppon those fforts of the Portingalls, which are uppon some ptes of his Domynions. In ye other wee have spoken of a thing of much mightier importance, yf any of Don Anthonyos sonnes will come into his Contry he shalbe assysted with mony and men, for the recovering of the rest of the Indyas. [37]

However, even if we allow these as sub-clauses to the agreement, Sir Anthony was skating on thin ice as far as the original sponsors of his mission were concerned.

At Isfahan, he was made a Mirza (prince) and, in May 1599, he was sent on an embassy to Europe, to win support for his plan. He travelled first to Russia, via the Caspian, as Turkey had become off-limits. With him he took a substantial party, including Husein Ali Beg, a venerable Persian ‘in disgrace … for some ill part that he had plaied,’ and a Dominican friar, Nicolão de Melo, whose involvement he mistakenly supported. Anthony’s younger brother, Robert, stayed behind as a ‘pawne’, or an assurance, for Sir Anthony’s conduct.[38]

De Melo wormed his way into the party by claiming he was King Philip’s Procurator General of the Indies. This was nonsense and, almost immediately, Anthony realised ‘he had waded somewhat too farre with this execrable frier.’ Not only did he have a predilection for courtesans but, as soon as two Christian boys were purchased to serve as his pages, Anthony found ‘he was in hand with them concerning his zodomiticall villainy.’ Eventually, in Astrakhan, he put de Melo under arrest. Their journey to Moscow was anything but harmonious: according to Parry, were it not for the Russian guard, ‘one of us had killed another.’[39]

In 1600, Russia was ruled by Boris Godunov. He was suspicious and distrustful, which ensured the embassy was received with hostility. The shah’s credentials referred to Sherley simply as a ‘passenger through the country’, which did not help. A smarting de Melo persuaded the tsar that Sherley was ‘but a man of meane parentage’ interested only ‘in purposes tending to his owne good.’ For a period, Anthony was imprisoned. At an audience following his release, in which de Melo made further accusations, his blood boiled over and, in front of the Russian commissioners, he ‘gave the fatte Frier such a sound box on the face’ that he fell ‘as if hee had beene strooke with a thunder-bolt.’ The show of spirit made quite an impression, and, in the end, Anthony’s revenge was complete. He denounced de Melo for ministering to Roman Catholics, and the friar was banished to a monastery on the White Sea. Nonetheless, the embassy to Russia was fruitless. It arrived in January 1600, was refused passage until after Easter, and obtained nothing.[40]

Even without de Melo, the rancour within the embassy persisted. At Archangel, Uruch Beg, Husein’s secretary (known as Don Juan after he converted to Catholicism), claimed that Anthony misappropriated the presents sent by Shah Abbas for Europe’s kings. It was said that, ‘for safety’, he put them on board a stout English ship in the harbour, rather than on the frail Flemish vessel which the Persians had intended for them. After that, they disappeared. Sherley claimed that the presents were ‘very unfitt to countenance out his Embassage’ and that he returned them to Persia. Uruch Beg insisted that they were sold by Anthony’s merchant friends in Russia. Their arguments reverberated for the rest of their European tour.[41]

Russia marked the low point in the embassy’s progress, yet its reception elsewhere was not as Anthony will have wished. In Rome, the Pope was predictably delighted, but everywhere there were squabbles over who in the entourage had precedence, something that the shah’s letters made far from clear. The French ambassador remarked that, since Sherley and Husein were in such disagreement, they were hardly likely to unite the Christian princes against the Turk.[42]

Other diplomats were left guessing about Anthony’s true purpose. In Prague, the Spanish ambassador suspected that he sought a shorter route for the spice trade, which by-passed Turkey and the Levant completely. Venice’s representative believed that he aimed at purchasing the captaincy of the mouth of the Red Sea from Spain, ‘to divert the India trade altogether from Egypt, and to send it through Muscovy.’ In Constantinople, the French ambassador believed Sherley had been sent by Elizabeth to persuade the shah to blockade Ormuz ‘and to declare that she would send her fleet to harass the Spanish in those quarters.’ When Sherley’s messenger, Angelo Corrai, told the Venetian Council of the Perso-Christian alliance against Turkey, they were sufficiently shocked that they told him ‘not to make himself known to anyone.’[43]

In England, the court was as unimpressed by Sir Antony’s mission as the Venetian Council. On 17 October 1600, Cecil wrote in a letter to the ambassador in Constantinople:

… you must know, that he went out of this Countrey, without any manner of allowance from her Majesty, nether was she ever, since his departure, consenting to any purpose or proiect of his … Her Majesty considering first of the state of those Contries, and the way for traffic, which is propounded, to passe through Moscovy, dyd not onely think the matter in it self altogether inconvenient, but dyd also forsee, how dangerous it might have ben to her Merchants trade with the Grand Signor yf any such fond practice, should have been sett on fote.

In addition, he reported that, when, from Emden, Anthony had requested permission to return home,

Her Majesty hath increased her former displeasure towards him so farr, in respect of this presumption, as by no meanes she will suffer him to come into the Kingdome.[44]

Where was Anthony to go? Accused by Husein of pilfering the shah’s gifts, he was unsure he would be welcomed in Persia. He offered his services to the French ambassador in Rome, but Cardinal d’Ossat was cautious. He knew that the Spanish had ‘made him fine offers to win him over to their side.’ Correctly, he surmised, ‘it may be that he, being far from his own country and in need of money, will accept a post from the Spaniards, who pay more for wrong-doing than for any other thing.’ Sure enough, the Spanish ambassador wrote to his King as follows:

The Englishman was very much bound to the Count of Essex, and since the latter’s imprisonment and death, he is completely without hope of ever again being admitted to the presence of the Queen … [so that] he is determined to serve Your Majesty should you so desire.

A few weeks later, Anthony was reported as having informed the Spanish about the best points on the English coast for the launching of an invasion. He told them of his plans for the Red Sea and of England’s intention of taking Jamaica and Santo Domingo. And so, having served the Earl of Essex, the Venetians, and the shah, Anthony entered the service of Spain. In that capacity, perhaps unaware that the Venetians already knew of Shah Abbas’s plan, he returned to Venice.[45]

In practice, whilst the Spanish were happy for Anthony to promote amity with King James of Scotland, they hadn’t forgotten his piratical career and they didn’t entirely trust him. Nor, of course, did the Venetians. They were none too pleased by his cosying up to Spain, a competitor power which controlled both Milan and Naples, and had the support of the Papacy. When, under the press of money, early in 1603, Anthony threatened a Persian merchant with violence, to obtain his silk, they used the opportunity to put him in prison. He was released after two months, on pain of leaving Venice for good. The expulsion was rescinded out of deference to James, when he became King of England, but it was reimposed when Venice discovered that Anthony was relaying intelligence about Turkey, obtained from the British ambassador in Constantinople, to Prague.

Thereafter, Sherley supplied Rudolph with intelligence, from Ferrara. In 1605, he was called to Prague itself and thence Rudolph sent him on a mission to Morocco. Sherley later served as a Spanish admiral in the Mediterranean, but unsuccessfully. He retired to Spain, from where, in utter dereliction of his promises to his former promoters, he wrote to Shah Abbas, ‘seeking by all means to divert the course of silk which hath been accustomed to pass by Aleppo, only to be transported by Ormus.’[46]

It is time to turn to his younger brother Robert who, it will be recalled, had been left in Persia as hostage for Anthony’s behaviour.

Sir Robert Sherley, Diplomat

That was in May 1599. In September 1600, he received a visit from John Mildenhall and John Cartwright. At first, Cartwright wrote, Robert was,

… kindly entreated by the king, and received large allowance; but after two years were fully expired, and no news of that great and important embassy; and the king perceiving that … the whole war was like to lie upon his own neck, without any help from the Christians, he began to frown on the English …[47]

By 22 May 1605, Robert was becoming desperate, as he made plain in a letter to Anthony:

I am soe besids my self with the travailes and wants I am in, and the little hope I have of your retorne or of anie man from yow, that I am almost distracted from the thought of anie helpe for my delivery out of this Contrey, I doe not altogether blame yow becawse I knowe yow have likwyse suffered discomodytie in those parts yow live in, thoughe they cannot be compared unto myne, consythering I live amongste turkes, infidells, and enymies to the Christian name … I cannot denie, but [the shah] giveth me still the same meanes he was wont: but God knows yt is in such a Scurvie fashion that I cannot possible meynteine myself with yt, and it is every yeare da mal in peggio.

Interestingly, as if to demonstrate that he, at least, had his eye on India, in this letter Robert stressed how vulnerable the Portuguese were feeling:

We have newes of ten flemishe shipps which laie before Goa, & put the Portugales in a mightie feare, insomuch that the Archbishopp impawned and sold all he had to make an Armatto against them, which being readie to goe forthe, the flemings went theare waies & they rest in such a feare, consythering there weaknes in all pts: that they sent a fryer by the waie of Turkey which was once with this Kinge upon an Ambassadge from the [Archbishop] of Goa, and goes now to signifie unto the king of Spaine, that except he send an Armie into the Indies to beate out the flemings, and to strengthen there garrysons, they must of force leave yt.

By September 1606, his patience with his brother was getting distinctly thin, and little wonder:

Your often promisinge to send presents, artiffisers, and Signor Angele (Sir Anthony’s interpreter), and I knowe not howe many els, hathe made me be estimed a common lyar; brother for Gods sake, eather performe, or not promis any thinge, becaus in this fassion you make me discredditt myself, by reporting things which you care not to effecte [48]

By now, however, the Emperor Rudolph had delegated power to his brother Matthias, who had concluded a peace with Turkey, and a deputation sent by the Pope was petitioning the shah to place the Armenians in Persia under the Church’s jurisdiction. To breathe life into his Christian alliance, Shah Abbas saw a need to send an ambassador to Europe. At the instigation of the papal mission, which acted out of gratitude for the assistance it had received from Robert, he agreed to send him. He departed in February 1608, ‘well accompanied and furnished’, and taking with him his young wife, Teresa. They travelled by way of Moscow, Krakow, and Prague, where Robert was elevated Count Palatine. In September 1609, they arrived in Rome, Robert dressed as a Persian, his turban surmounted by a crucifix of gold to show his Christian faith.

From there, he travelled to Madrid. But King Philip kept him waiting. He had, he said, often been ‘cozened’ with embassies from far-off countries like Persia. Robert was greatly dissatisfied. Finally, after a year, he turned to the English ambassador, Francis Cottington, promising that he could offer ‘his natural Sovereign’ the use of two ports, customs-free trade, and a supply of silk at prices that would yield a profit of seven hundred per cent. Cottington asked why the offer had not been accepted by Spain, and was told,

Because I do require that this King do make Invasion of the Turk, and that the Imposition of 23 per 100, be taken off at Lisbon, so that Portugese Commodities be sold at easier rate; but in England I will only propound the settling of a trade, and because you shall understand why the Persian shall be contented with that trade only, it is because by it will be diverted that great course of traffick to Constantinople and Aleppo, to the great loss of his enemy the Turk.[49]

In his dispatch, Cottington recommended the scheme, adding ‘in my poor opinion to those vices which in Sir Anthony do so abound, in this man may be found the contraries.’ And so – despite the best efforts of his brother Anthony, who attempted to block his departure – Robert sailed to England. He first visited Wiston, where his father – still living, but broken in health and fortune – informed him that his eldest brother was prisoner in the King’s Bench for debt. About him Robert could do little, but he intervened with Lord Salisbury on his father’s behalf, and Cecil arranged for proceedings against him to be stayed. (Robert’s father died in December 1612.)[50]

Although his expectations for it were exaggerated, Robert’s efforts to direct Persian trade towards England appear to have been sincere, and the response he received from King James was positive. In March 1612, Sherley informed Lord Salisbury,

… his maiesty is determyned to make a combynattion betwext this state and the Persian … to the eande that if the Spanniard at any tyme shoulde intimat any thinge this way, [his] maiesty myght be assured in the East Indies of a Potent frende, Plases for Landin on, and assistans in what soever may bestt advantage sutche affars; his maiesty hath lykwys consented that I may now make my retorne from hence with a Shipe, and a Pinnis, If I can procure my frends [to] be at a part of the Chardge, havinge promised graci[ously] to geve me assistance lykwys in that particular …

He pointed out that his expedition would supply valuable intelligence on whether the Persian ports ‘may be advantigable to annoi the Spanniard if neede shall require,’ but various forces conspired to frustrate him. In the vanguard were the Levant merchants, who were anxious for their overland trade, and the East India Company, who were familiar with James’s habit of granting licences that infringed on their monopoly. They were joined by the ambassador of Spain, and by George Abbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had no time for friends of the Pope. ‘The King of Spain has an advantage in England, because he can avail himself of discontented Catholics,’ he wrote. They should not be encouraged. In any event, he understood that the Persian and Turk had agreed on points of trade, so he declared that ‘Sir Robert Sherley’s negociation is over, and he may go back when he pleases.’ Robert returned to Persia empty-handed.[51]