Dufferin at Clandeboye and in High Latitudes

Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, was born on midsummer’s day 1826, in Florence, where his parents, Price and Helen Blackwood, had moved to take refuge from Price’s family. They so disapproved of their son’s choice of bride that they had refused, point blank, to attend his wedding.

The Blackwoods were sensitive to status. They controlled two estates in County Down, including the family seat at Ballyleidy, but they were, at heart, country squires who had used the instrument of marriage, particularly with the Hamiltons of Killyleagh – the Viscounts of Clandeboye – to raise themselves in the world. In 1800, they capitalised on British concern for stability during the Napoleonic Wars to obtain (in exchange for support for the Act of Union) the Barony of Dufferin and Clandeboye. Yet, in the family, only Sir Henry, who attended Nelson at Trafalgar, had any great claim to fame and, since then, the family’s wealth and station had progressively dissipated.

In part, the Blackwoods’ disappointment over their son’s marriage reflected their dependence on him for their fortune. Frederick’s first brother had been killed at Waterloo. His second died shortly afterwards in Naples, where he had been sent to evade the clutches of an impecunious fancy, Miss Stannus.[1]

Another concern, however, was that Helen was the granddaughter of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright, womaniser and profligate, whose meteoric rise in parliament had guttered into drunken failure and near bankruptcy, in 1816. In 1830, the Prices’ opinion of the Sheridans appeared to be vindicated by the ‘shocking’ marriage of Helen’s sister, Georgia, to Lord Seymour, heir to the Duke of Somerset. The marriage of another sister, Caroline, to the brother of Lord Grantley, proved a disaster and, after 1836, the news of her affair with the prime minister, Lord Melbourne, became the stuff of public scandal. In 1835, brother Brinsley administered another shock to society by eloping to Gretna Green with the daughter of Sir Colquhoun Grant, thereby securing a fortune.[2]

Like his uncle, Sir Henry, Price pursued a career in the Navy. In September 1834, he led an attack to force the passage of the Bocca Tigris, near Canton, but his attempt to capitalise on this to build a political career ended in his humiliation and possible suicide only a few years later, in 1841. Left alone, Helen was more determined than ever to shape Frederick’s destiny and, through him, to restore the pride of the Sheridans. She had high ambitions for her son, and they centred in England.[3]

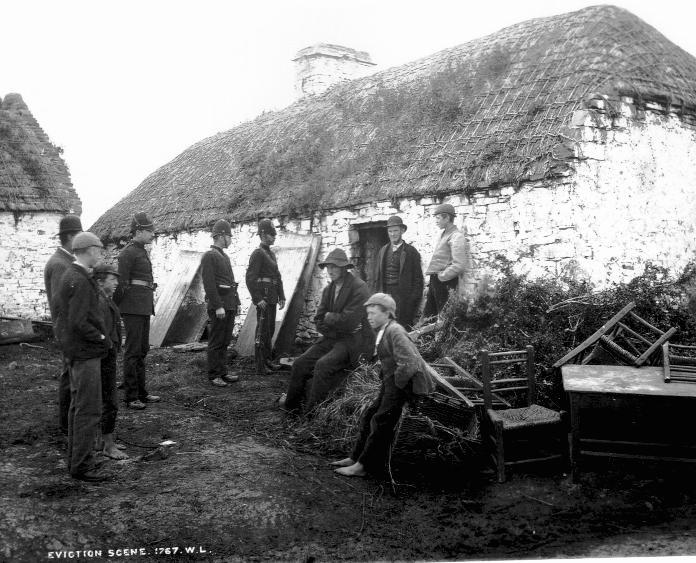

His first port of call was Eton, where Frederick became the friend both of Robert Cecil (later Lord Salisbury) and of John Wodehouse (Lord Kimberley). At Christ Church, Oxford, however, he avoided the society of the best-connected, whose privileges, he decided, were often undeserved. He became most preoccupied by the state into which, from 1845, Ireland had fallen, as a result of the potato famine. In 1847, he visited County Cork with his friend, George Boyle, to experience it at first hand. Afterwards, they published a Narrative of a Journey from Oxford to Skibbereen, to bring the famine’s horrors to public attention. The also made a determined effort to collect funds for its victims.

[He wrote] We have just returned from a visit to Ireland, whither we had gone in order to ascertain with our own eyes the truth of the reports daily publishing of the misery existing there. We have found every thing but too true; the accounts are not exaggerated – they cannot be exaggerated – nothing more frightful can be conceived. The scenes we have witnessed during our short stay at Skibbereen, equal any thing that has been recorded by history, or could be conceived by the imagination. Famine, typhus fever, dysentery, and a disease hitherto unknown, are sweeping away the whole population …

… they were compelled to suffer multitudes to lie on the damp mud floor of their own cottages, the only alleviation being, that the frequency of deaths made continual room for new inmates. Some had even died in this uncared-for condition, and their dead bodies had lain putrifying in the midst of the sick remnant of their families, none strong enough to remove them, until the rats and decay made it difficult to recognise that they had been human beings.[4]

That summer, Dufferin left Oxford without taking his degree. He returned to Ballyleidy, where he supported his tenants with rent reductions and a series of works to the house and grounds designed to provide them with employment. That year his debts rose to £29,000. Although the estate produced a theoretical yearly income of £18,000, his tenants were £30,000 in arrears, and annuities owed to the other members of his family reduced Dufferin’s annual revenue to a much less impressive £4,600. Already, his finances had become stretched.[5]

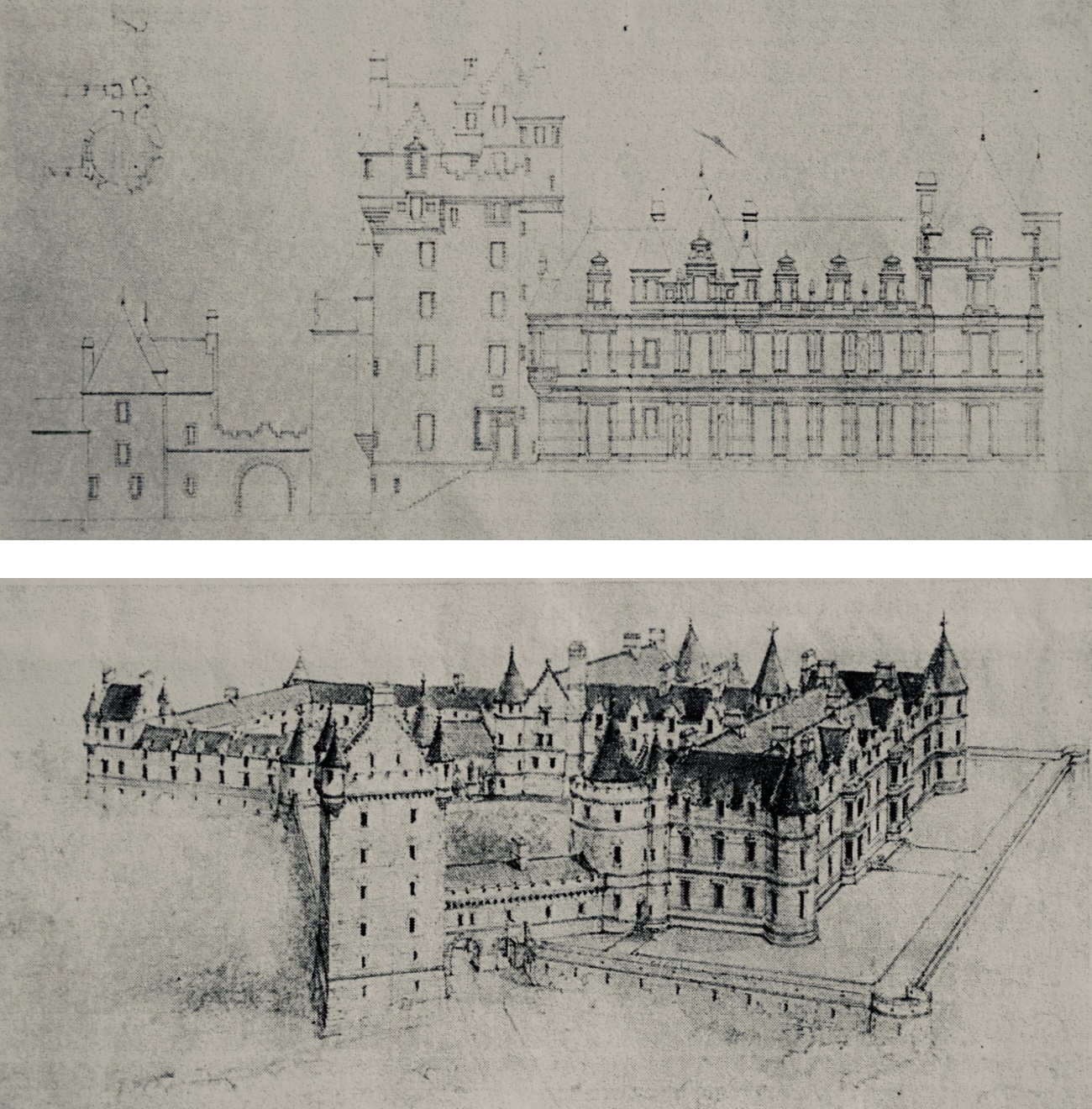

In 1849, Dufferin’s ambitious mother used her connections with the Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, to secure him a position at Queen Victoria’s court. His moving in new, elevated circles was to stimulate Dufferin to dreams of transforming Ballyleidy—now renamed Clandeboye—from a late Georgian ‘debased Hibernic’ country house into a ‘Jacobethan’ mansion, in the style of the Duke of Sutherland’s Dunrobin and the Duke of Argyll’s Inveraray. Plans were prepared by the architect William Burn, but the cost was vastly greater than Dufferin could afford and all that eventuated was ‘Helen’s Tower’, a gothic folly in the spirit of Sir Walter Scott, built in tribute to his mother. It took until 1861 to complete. At its heart, in a panelled chamber, is the inscription of a poem dedicated to her, which Dufferin commissioned from Tennyson.

A similar chivalric spirit led Dufferin to propose the tribute of a golden rose to settle a dispute with his Hamilton cousins over their claim to the Gate House at Killyleagh Castle, and to commission Benjamin Ferrey to decorate a room at his home at Grosvenor Place ‘in the style of Edward IV.’ Ferrey also had a hand in the design of the railway station built in the Clandeboye grounds at Greypoint, later renamed ‘Helen’s Bay’. From this, Dufferin built a stairway to an avenue below, which passed through a bridge designed like a medieval city gate and ran for three miles past open parkland and a new lake to the house. By the time all this was finished, Dufferin had spent £70,000 he could ill afford. Yet this was not the end to his extravagance. He was to indulge in another pastime – adventure at sea.[6]

In 1854, Dufferin borrowed £3,000 to buy an ocean-going schooner, the Foam, which he took to the Baltic. This was the time of the Crimean War and, upon his arrival at the Åland islands, the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Charles Napier, offered the intrepid voyager the opportunity ‘to see a shot pass over him.’ Dufferin and his cousin, Stanley Graham, a midshipman serving with Sir Charles, saw rather more than they, or Sir Charles, anticipated, for, no sooner had they boarded HMS Penelope, than she ran aground under the guns of the Bomarsund Fort. Dufferin writes,

… At first, I could not help ducking each time a cannon ball hurtled overhead. At last, bang went a round shot through both our paddle boxes. Having heard that it was a prudent measure to put one’s head into the first hole made by a cannon shot in a vessel’s side, though disdaining to practice the experiment, I determined to watch whether it would have been successful. A minute or two afterwards there came another shot within two or three feet of the first, and immediately after a third, which knocked the previous two holes into one, a circumstance which satisfied me the theory did not hold water.

For two hours, the Penelope drew heavy fire. Dufferin derived ‘a certain satisfaction’ from his lack of nervousness when, in his immediate vicinity, a splinter buried itself in the brain of one man, and another ‘had the top of his skull taken off as clean as if it had been done with a knife.’ Next, a cannon ball struck the deck within a couple of feet of Dufferin’s toes. Still, it was with reluctance that he eventually agreed to get out of harm’s way. Dufferin writes,

My instinct was to demur at [the captain’s] suggestion, for I naturally desired to see the affair through; but, as I did not feel justified in adding to the commander’s anxieties at so critical a moment, I obeyed his orders, on condition that he would afterwards write us a note to say that it was at his especial request that we were deserting his ship.

Dufferin retired to the supposed safety of HMS Hecla, which, although also within the range of the fort’s guns, had the advantage of being afloat. Of course, she was exposed to similar danger. Dufferin recalls,

I had just gone forward for a better view, when smash comes a round shot, striking the deck close by the starboard great gun, and covering me with a hail of splinters. The men were very angry at being exposed to fire in this way, and cursed Sir Charles for not covering them with one of his big block ships.

Not content with this, the next day, Dufferin’s party visited the trenches of the French army besieging Fort Tzee. After stopping ‘to breathe and chaff the soldiers – shot, shell, and grape whizzing every now and then over our heads, and everybody laughing beneath,’ they observed a white flag and strolled up to one of the gates. Sharply, they were ordered back by a Russian officer who rushed out, excitedly crying out that the place had not surrendered. Dufferin writes,

The predicament was serious, for our only chance was to take the shortest cut back to our own battery, which might be expected to open fire in our faces at any moment, while the Russians would be quite entitled to pot us from behind.

True enough, no sooner had he returned to cover than Dufferin learned that grapeshot had been peppering the place where he had stopped to take a final view. He wrote that ‘the tops of the little fir trees all about looked as if they had been cut off with a reaping hook.’

Eventually, the fort and its 1,600 men were carried. Dufferin set sail the next day, and, after a month’s cruise, he landed at Dunrobin in Scotland with ‘two beautiful field pieces’ which he had won off the French admiral, and a young walrus he had bought on the homeward route.[7]

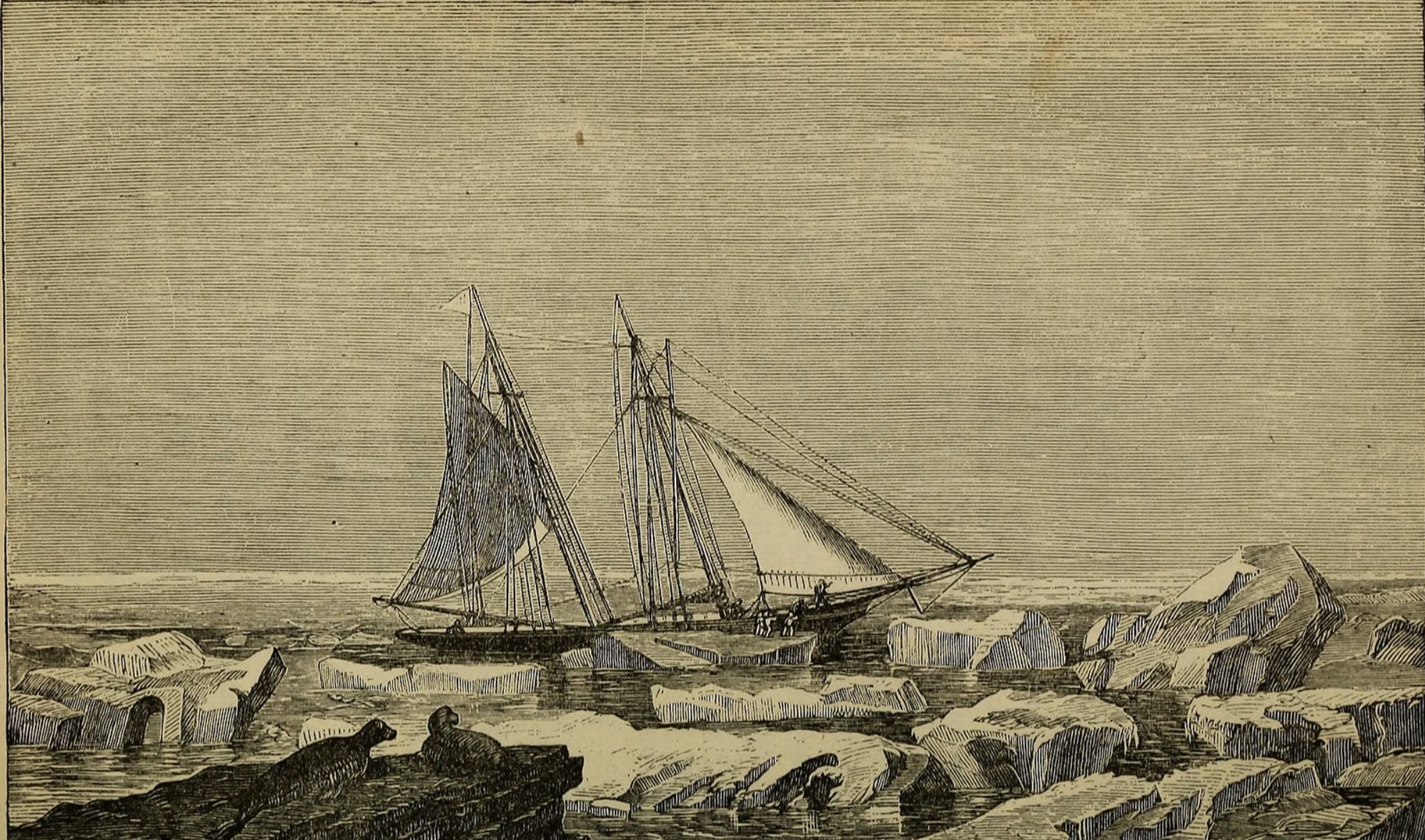

In 1856, Dufferin took the Foam on an expedition to Iceland, Jan Mayen Island and Spitzbergen – which was almost as far north as any ship had, at that time, sailed. The account he published of his journey, Letters from High Latitudes, made him quite a celebrity. He presented a copy bound in driftwood to his Queen and, later, when he passed through Berlin on a mission to Russia, it was only because of the reputation for intrepidity that it had afforded him that Bismarck agreed to a meeting.

One of the book’s most entertaining moments consists in Dufferin’s account of ‘Scandinavian skoal-drinking’ at Government House, Reykjavik, in which he demonstrated an impressive resilience to alcohol:

After having exchanged a dozen rounds of sherry and champagne with my neighbours, I pretended not to observe that my glass had been refilled … Then came over me a horrid wicked feeling. What if I should endeavour to floor the Governor! … It is true I had lived for five-and-twenty years without touching wine; but was not I my great-grandfather’s great-grandson, and an Irish peer to boot? … So, with a devil glittering in my left eye, I winked defiance right and left, and away we went at it again for another five-and-forty minutes … It is true I did not feel comfortable; but it was in the neighbourhood of my waistcoat, not my head, I suffered … guess then my horror, when the Doctor, shouting his favourite dogma, by way of battle cry, “Si trigintis guttis, morbum curare velis, erras,” gave the signal for an unexpected onslaught, and the twenty guests poured down on me in succession …

Although up to this time I had kept a certain portion of my wits about me, the subsequent hours of the entertainment became thenceforth enveloped in a dreamy mystery. I can perfectly recall the look of the sheaf of glasses that stood before me, six in number; I could draw the pattern of each; I remember feeling a lazy wonder they should always be full, though I did nothing but empty them … The voices of my host, of the Rector, of the Chief Justice, became thin and low, as though they reached me through a whispering tube; and when I rose to speak, it was to an audience in another sphere, and in a language of another state of being: yet, however unintelligible to myself, I must have been in some sort understood, for at the end of each sentence, cheers, faint as the roar of waters on a far-off strand, floated towards me …

The Rector, in English, proposed my health – under the circumstances a cruel mockery – but to which, ill as I was, I responded very gallantly by drinking to the beaux yeux of the Countess … Then came a couple of speeches in Icelandic, after which the Bishop, in a magnificent Latin oration of some twenty minutes, a second time proposes my health; to which, utterly at my wits’ end, I had the audacity to reply in the same language …

“Viri illustres”, I began, “insolitus ut sum at publicum loquendam ego propero respondere ad complimentum quod recte reverendus prelaticus mihi fecit, in proponendo meam salutem; et supplico vos credere quod multum gratificatus et flattificatus sum honore tam distinco …”

The night ended with the party hunting rabbits on a nearby island:

They were quite white, without ears, and with scarlet noses. I made several desperate attempts to catch these singular animals, but …. [they] made unto themselves wings and literally flew away! …. With some difficulty we managed to catch one or two …. They bit and scratched like tiger cats, and screamed like parrots; indeed …. I am obliged to confess that they assumed the appearance of birds, which may perhaps account for their powers of flight.

Puffins!

The book is not without its more poetic moments, however, as this account of the final approach to Jan Mayen confirms,

Hour after hour passed by and brought no change. Fitz and Sigurdr, who had begun quite to disbelieve in the existence of the island, went to bed, while I remained pacing up and down the deck anxiously questioning each quarter of the grey canopy that enveloped us. At last, about four in the morning, I fancied some change was going to take place; the heavy wreaths of vapour seemed to be imperceptibly separating, and in a few minutes more the solid roof of grey suddenly split asunder, and I beheld through the gap, thousands of feet overhead, as if suspended in the crystal sky, a cone of illuminated snow.

To celebrate the journey, Dufferin placed two narwhal tusks at the foot of the stairway at Clandeboye. They are still there today – as are a model of the Foam, its cannon and the pelt of a polar bear in the hall. They represent the beginning of the transformation of the house’s interior into a kind of museum commemorating Dufferin’s extraordinary career.[8]

Flushed with his success, in 1858, Dufferin invested another £3,000 in a new 220-ton yacht, the Erminia, in which he took his mother, a crew, three dogs, a jackdaw, two parrots, a goat and a sheep on a cruise of the Mediterranean. In Alexandria, he had an audience with Said Pasha, the ruler of Egypt, whom he describes as ‘a good natured, irascible, bustling, childish man’ given to ‘the most infamous of practices,’ who survived in power only by ‘allow[ing] everyone to cheat him.’ Thence, Dufferin travelled to Deir-el-Bahri where he financed some archaeological excavations, uncovering a cartouche of Tirhakah, a granite altar of Mentuhotep I, a statue of the god Amun and a toe from a statue Ramses II. (The complete bust was immovable.) These too have found their place at Clandeboye – the altar now supporting the massive head of a rhino. (The Amun was sold in 1937; its place at the top of the stairs was taken by a Burmese Buddha, taken from Mandalay, in 1886.) [9]

Following these and other experiences in the Levant, Dufferin was appointed emissary to Syria, in 1860. There, he established his diplomatic credentials by helping to avert a civil war. His rewards were the KCB, the offer of the governorship of Bombay and the prospect of being Viceroy ‘by forty’. But Dufferin stayed at home, and, in October 1862, he married his cousin, Hariot Hamilton. A painting at Clandeboye shows them as newly-weds processing along an upper landing. The scene has hardly changed since, even to the extent of the narwhal tusks showing above the top of the stairs.[10]

Dufferin’s expenditure continued. By 1864, it had been such that he was obliged to take on a £21,000 mortgage to keep afloat. These were followed by further mortgages totalling £43,000. Yet, he persisted with commissioning grand schemes for remodelling Clandeboye – first in gothic (Benjamin Ferrey) and then as a French chateau (William Lynn). Given the state of his finances, however, these were just flights of fancy.

In 1869, Dufferin finally settled for a more modest, but unusual, plan. Reversing the layout of the ground floor, he set an unobtrusive front door into the blank wall of what is still ostensibly the back of the house. Today, when this is opened to the visitor, he is greeted by a hall-cum-museum, its walls hung with weaponry. Beyond, a small staircase rises, as in an ancient Egyptian tomb, leading the eye to where the statue of Amun would have once stood. It is a most impressive display.[11]

Although it represented a significant scaling-back in Dufferin’s ambitions, it failed to avert the inevitable. Between 1874 and 1880, Frederick was forced to sell 11,000 acres of land (two-thirds of the estate he had inherited) to local industrialists. Before then, spending on his properties, the drawing of annuities by his relatives, and reductions in rents, had caused his debts to balloon to £300,000.[12]

Dufferin in Quebec and Simla

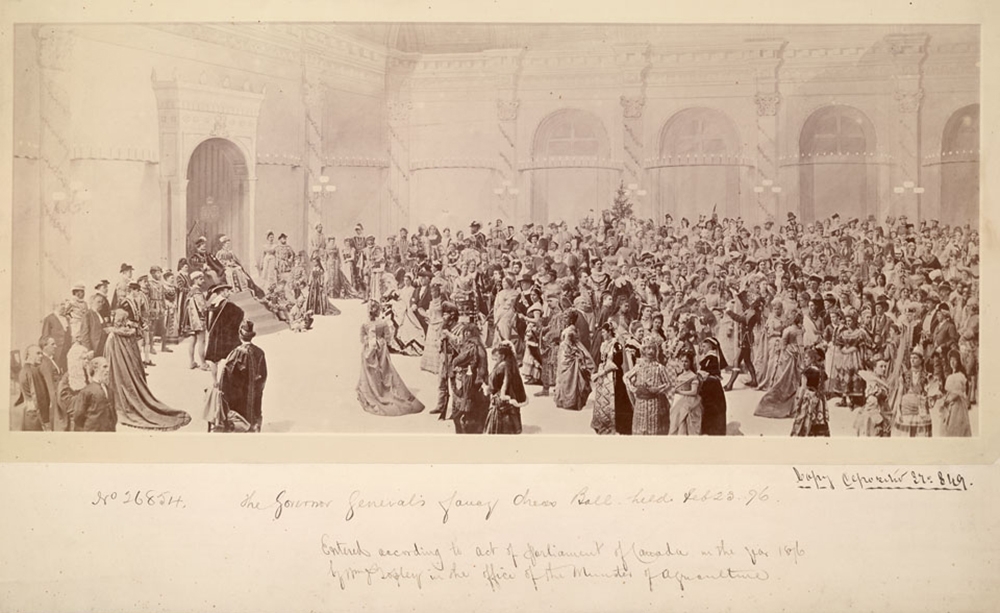

In 1872, however, Dufferin was served a temporary lifeline when he was appointed Canada’s third Governor General. With the post came a salary of £10,000, and an opportunity to indulge himself at the public expense. Dufferin was highly popular. Little wonder: the records at Clandeboye indicate that, between 1873 and 1878, he entertained no fewer than 35,838 people at dinners and balls. To Rideau Hall, his official residence in Ottawa, he added the ballroom, in 1873, the tent room, in 1876, and – with a personal donation of $1,600 (later refunded) – a skating rink, which was opened to the public. For the inauguration of the tent room, a fancy-dress ball was held for 1,500 guests.

Upon his arrival, Dufferin had found Rideau Hall ‘hideous’. Ottawa was judged little better, although the parliament building, then emerging from the mud, he considered to be in better taste than its Westminster model. Quebec made an altogether better impression. Dufferin converted the officers’ mess on the citadel overlooking the St. Lawrence into a summer residence. It became a venue for multiple summer receptions.

There were some disappointments. When Dufferin heard of plans to destroy Quebec’s ancient walls, he opposed them, proposing instead that the city be recreated as a ‘Canadian Carcasonne’. William Lynn was engaged. Dufferin petitioned the Queen for cash, but, in the end, he had to settle for restoring the gateways and constructing ‘Dufferin Terrace’ along the ramparts. He aimed to protect French Quebec against ‘the brutality of the John Bull element and the vulgarity of the emigrant classes,’ and, by the time of his departure, he considered that he had ‘in great measure saved the English population from Yankification.’ Old Quebec was recognized as a World Heritage Site, in 1985.[13]

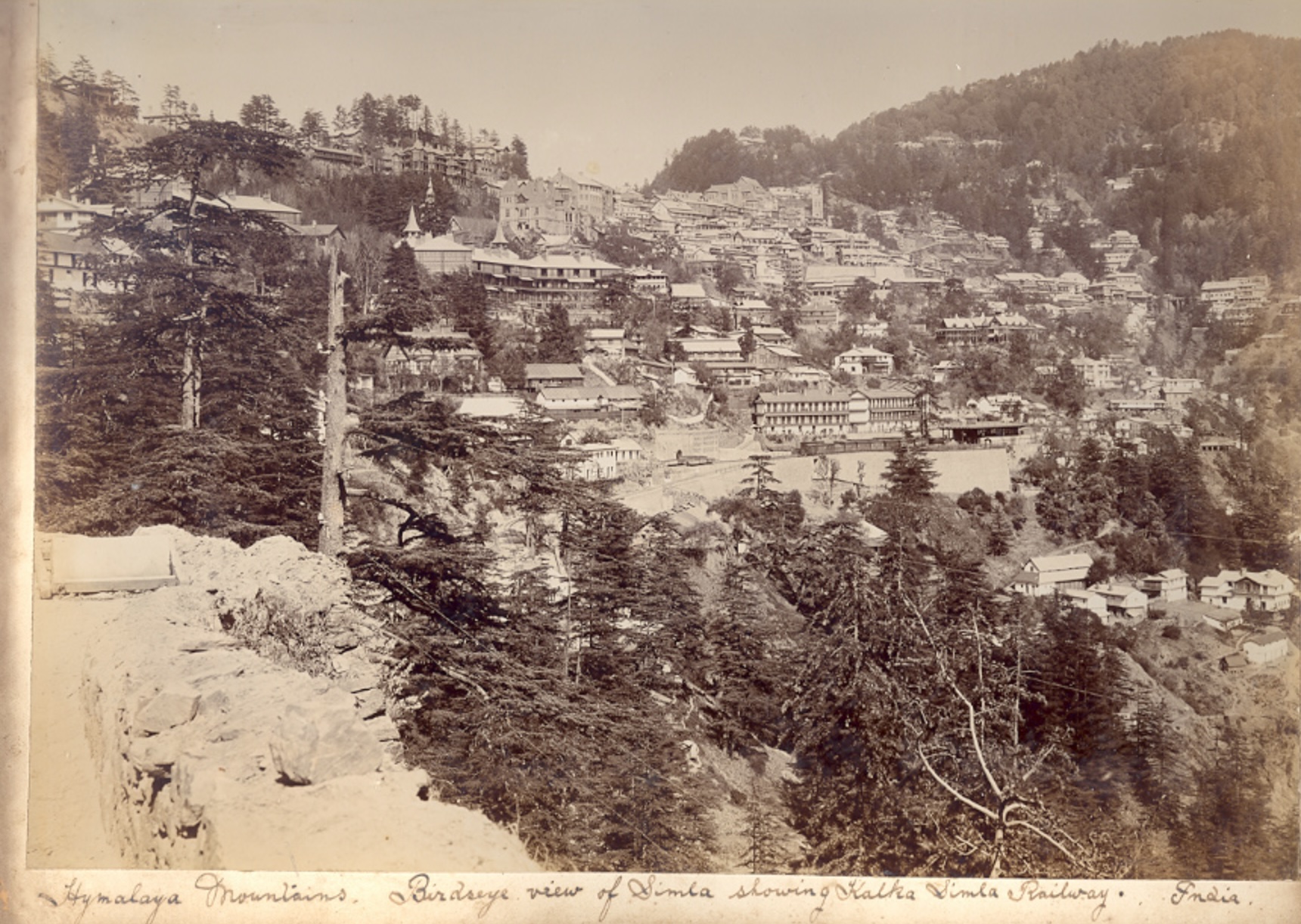

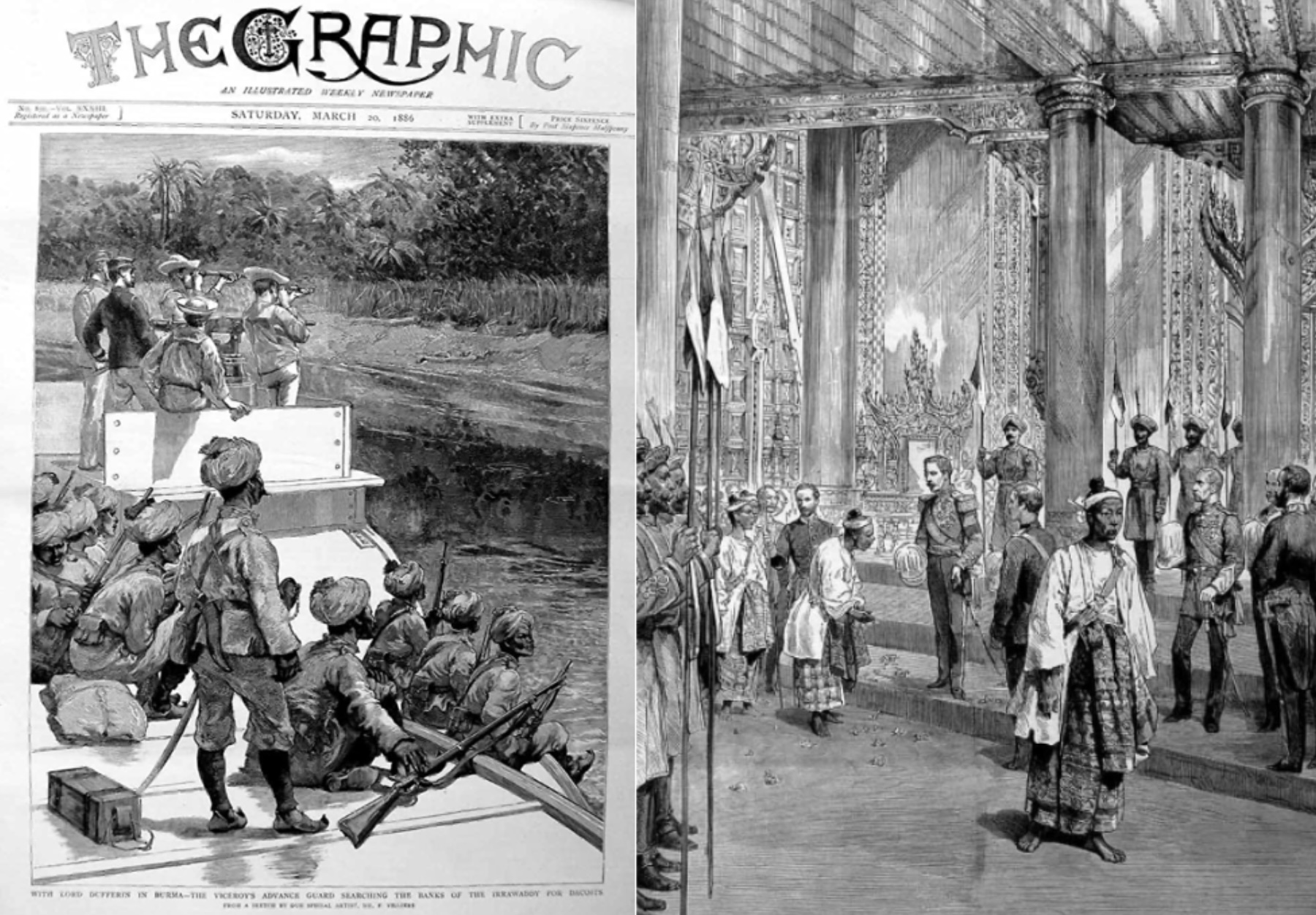

After two years in St. Petersburg (1879-81) and three in Constantinople (1881-84), Dufferin became Viceroy of India, in 1884. In addition to a tiger skin, which joined the polar bear on the hall floor, India supplied Clandeboye with much of the weaponry decorating its walls. The library houses a magnificent collection of photographs of the Raj at work, and of the annexation of Upper Burma. (Dufferin shipped home the day bed on which King Thibaw and Queen Supayalat were photographed shortly before their deposition.) Most especially, however, India provided Dufferin with the object of his dreams: a great house, built not in County Down but at Simla, in the foothills of the Himalaya.

The annual migration of the government of India, over 1,200 miles and to an altitude of 7,000 feet, to escape the heat of Calcutta, had started some 20 years before. Not everyone thought it an excellent idea. Kipling, for one, questioned the wisdom of retreating to a place that was one hundred miles from the nearest railway, ‘on the wrong side of an irresponsible river’ and ‘separated by a month’s sea voyage’ from the rest of the country.

The idea had been that of John Lawrence, viceroy from 1864 to 1869. Simla suited his preoccupation with the Punjab and the North-West Frontier: he claimed he achieved more in one day there than he did in five on the eviscerating plains below. (He also liked the way the rain on one side of the ridge followed the Sutlej and Indus to the Arabian Sea and, on the other, the Ganges to the Bay of Bengal.). Others were more principled. Never mind that the Bengal climate had killed off three consecutive governors-general, argued Sir Henry Durand, ‘It was a condition on which India had been won and could only be kept, that men on high place must risk health and life in the execution of duty.’ (Durand met his end when the elephant on which he was processing charged an arch too low for his howdah.)[14]

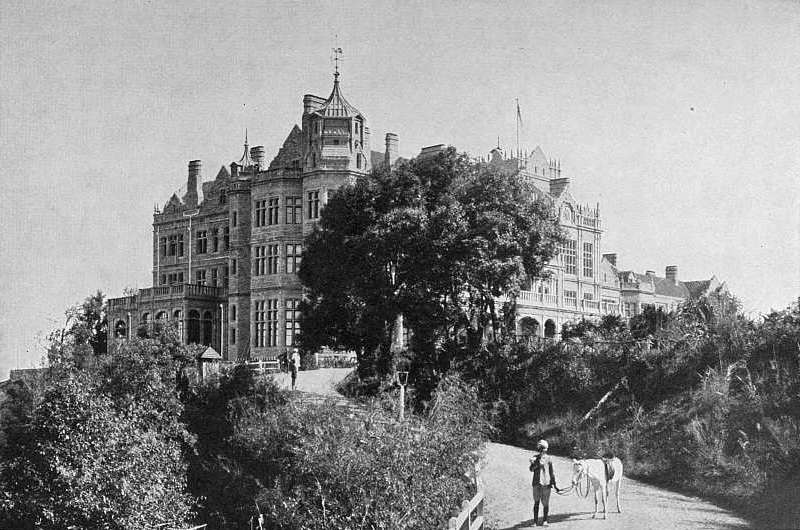

Dufferin was good enough to concede it was ‘too absurd’ that the capital of India should be ‘hanging by its eyelids to the side of a hill,’ yet he was no more capable than his predecessors of resisting the idea. Moreover, it gave him a chance to build the grand seat he wished for Clandeboye. Thus far, the viceroys had had to make do with the ‘Peterhoff’, which Lady Dufferin called a ‘cottage’. She objected that it served to entertain only twenty-three people comfortably.

At the back of the house [she complained] you have about a yard to spare before you tumble down a precipice, and in front there is just room for one tennis court before you go over another. The ADCs are all slipping off the hill in various little bungalows, and go through the most perilous adventures to come to dinner.[15]

In 1876, Lord Lytton called the Peterhoff ‘a sort of pigstye.’ (He had declared Victoria Empress of India, so holding durbars of the Indian princes in a marquee on the lawn did not suit his style.). For a while, Dufferin toyed with the idea of enlarging it but, in the end, he decided it was better to begin afresh. He engaged the local Superintendent of Works, Mr. H Irwin, and Captain HH Cole of the Royal Engineers to draft a proposal but involved himself intimately in the details of their designs. For two seasons, to the irritation of many, he visited the building site almost every morning and evening to offer his advice.

Not all subsequent viceroys, or their wives, were impressed by the result. To Lord Lansdowne, Dufferin’s successor, who welcomed the English homeliness of it, the ‘whole arrangement of the rooms and anatomy of the building tell a tale of amateur architecture.’ Lady Curzon, an American, was quite disparaging. ‘A Minneapolis millionaire would revel in it,’ she smirked. Edwina Mountbatten shared her opinion, but with less humour. She called it ‘hideous, bogus English Baronial, and Hollywood’s idea of a Viceregal Lodge.’ Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India between 1917 and 1922, thought it like ‘a Scottish hydro – the same sort of appearance, the same sort of architecture, the same sort of equipment of tennis lawns and sticky courts.’

Certainly, it incorporated many novel features – an indoor tennis court, white tiled kitchens in the basement, and electric lights. Lady Dufferin found it ‘quite a pleasure to go around one’s room touching a button here and there.’ Mockingly, she wondered what the dhobies would make of the laundry. ‘Now,’; she wrote, ‘they will be condemned to warm water and soap, to mangles and ironing and drying rooms’ rather than to ‘flog and batter our wretched garments against the hard stones until they think them clean.’ Not too seriously, she wondered whether they would feint with the heat.

The design of the Viceregal Lodge features several of Dufferin’s earlier ideas for Clandeboye: Elizabethan, with Jacobean turrets, balconies, heraldic crests and motifs. Column arches support verandahs on the first and second floors. These are roofed with glass cubes laid into iron frames, designed to diffuse the rays of the tropical sun. The roofline is broken up with gables, a domed turret with a weathercock and, in a statement of power, a small tower from which a flag was flown when the viceroy was in residence. The highlight of the interior is a huge hall in teak, walnut and deodar, with a three-storey gallery and staircase. The dining room sat nearly seventy. In her 1939 account, Audrey Harris described the candlelight as glowing into infinity. She wondered whether the silver urns on display contained the ashes of former viceroys.

In keeping with its progenitor, this was a project that came with a huge budget. It cost £100,000. Dufferin claimed that it was ‘beautiful, comfortable [and] not too big.’ Yet it could accommodate eight hundred guests for balls and parties. Sir Richard Cross, the Secretary of State at the India Office, who had to foot the bill, was presumably less than convinced by the modesty of Dufferin’s conception.[16]

After stints in Rome and Paris, Dufferin retired from the diplomatic service, in 1896. The Viceregal Lodge had sated his building ambitions, but an annual pension of £1,700 hardly matched the lifestyle to which he had become accustomed. The solution lay in directorships in the City. And, for companies seeking the endorsement of a respected celebrity, there were few better catches than the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava.[17]

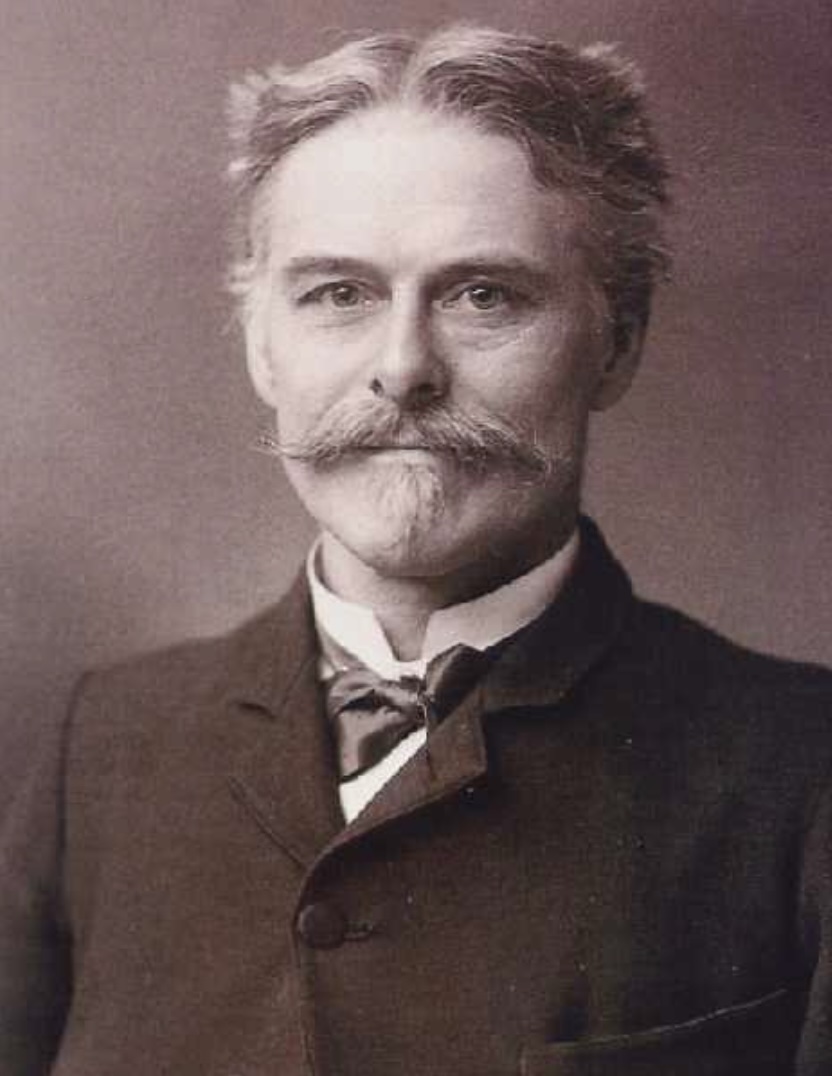

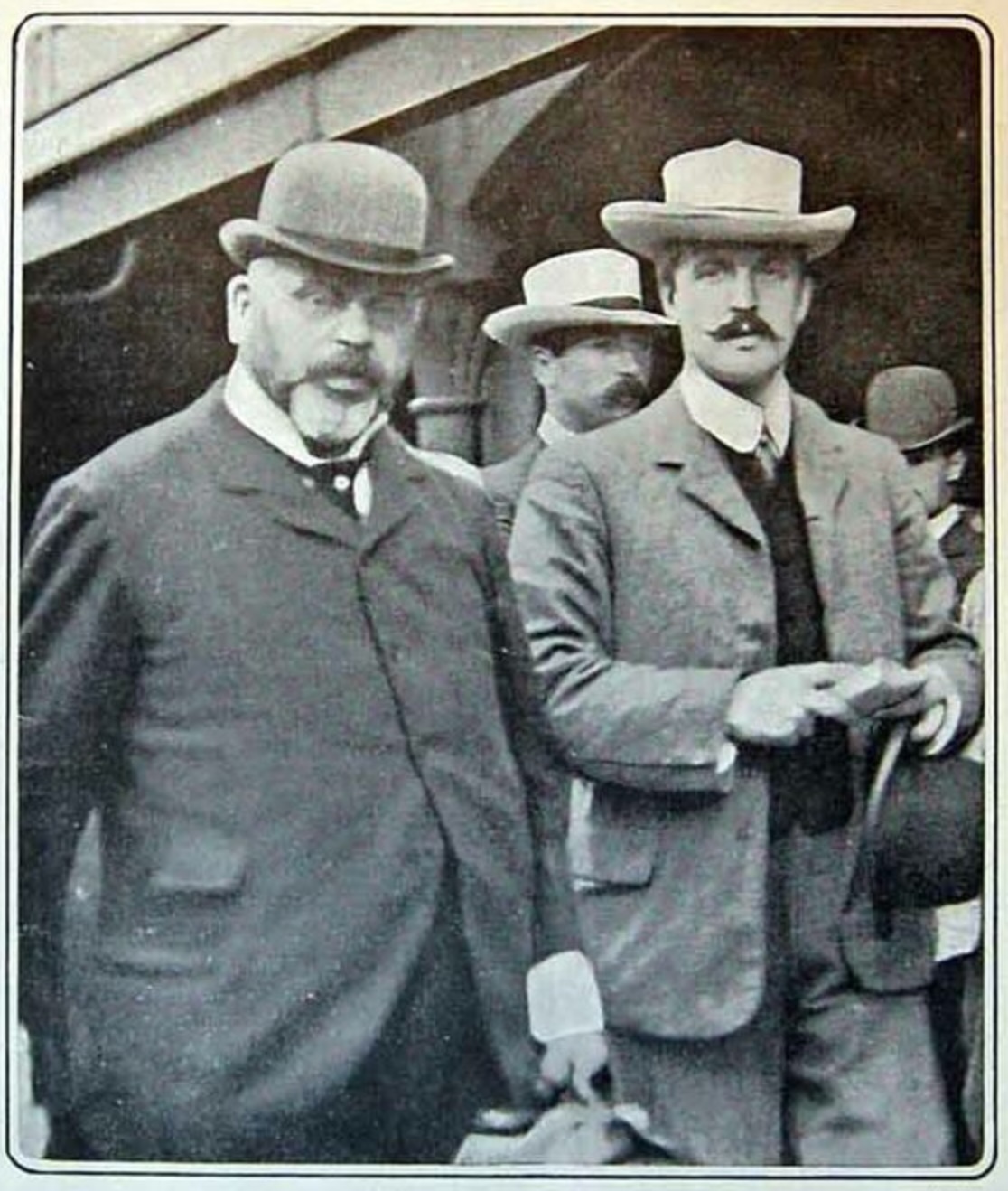

So it was that, in 1897, Dufferin was offered the chairmanship of the London and Globe Finance Corporation. To sweeten the offer, alongside his £3,000 annual salary, he was granted a signing-on fee (amount undisclosed) and dispensation from the need to attend board meetings.

Whitaker Wright, London & Globe and Witley Park

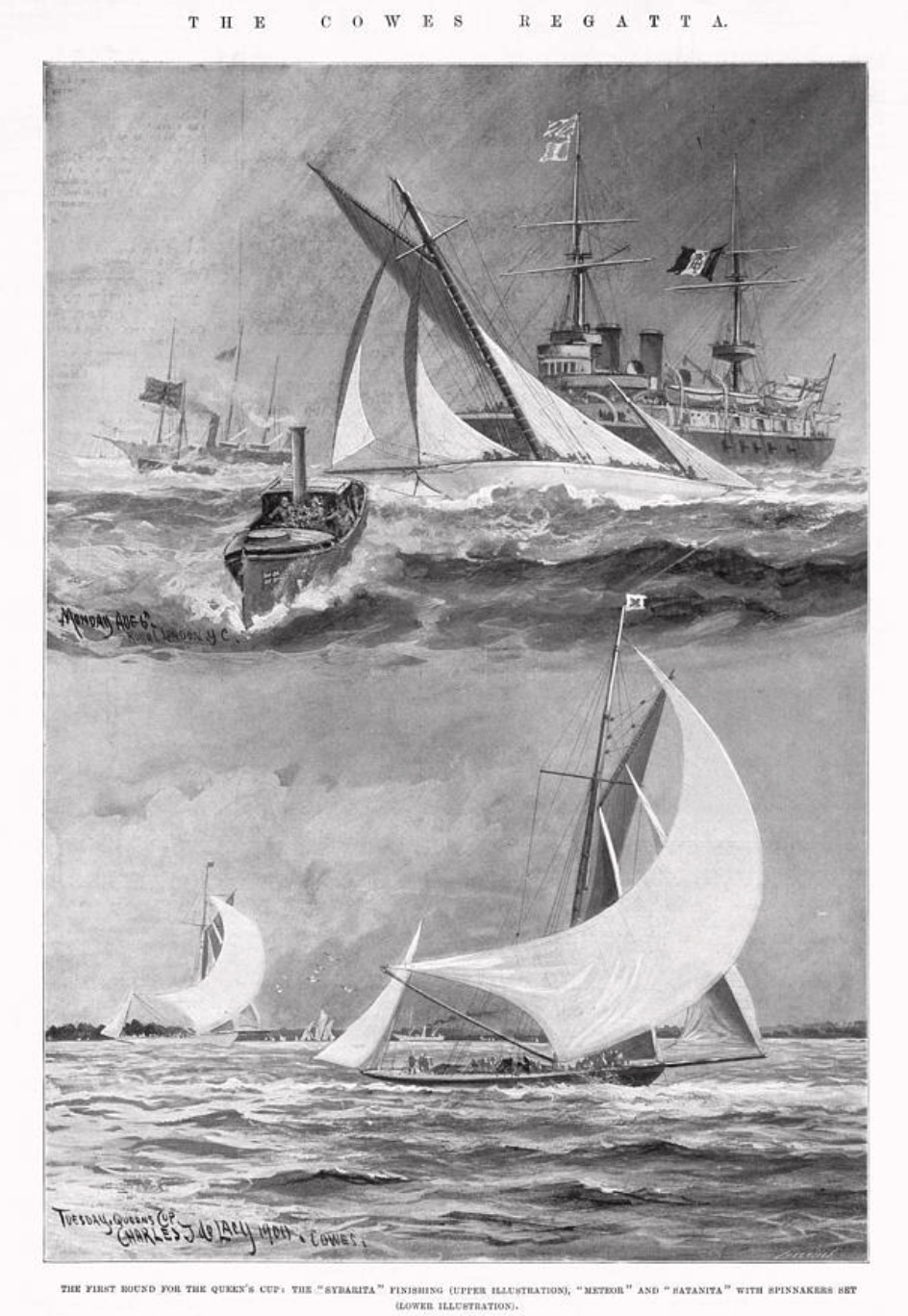

The London and Globe was the creation of James Whitaker Wright, one of the City’s greatest plutocrats. He lacked pedigree, but Dufferin was seduced by his reputation as a Croesus, by parties at his magnificent estate in Surrey, and by sailing trips aboard the Sybarita, the yacht which had raced the Kaiser’s Meteor, at Cowes. He let down his guard. Not only did he accept the offer, but he also invested substantial sums in this and Whitaker Wright’s other companies. The decision proved disastrous. It is time to tell something of the Whitaker Wright story and of its spectacular unravelling.[18]

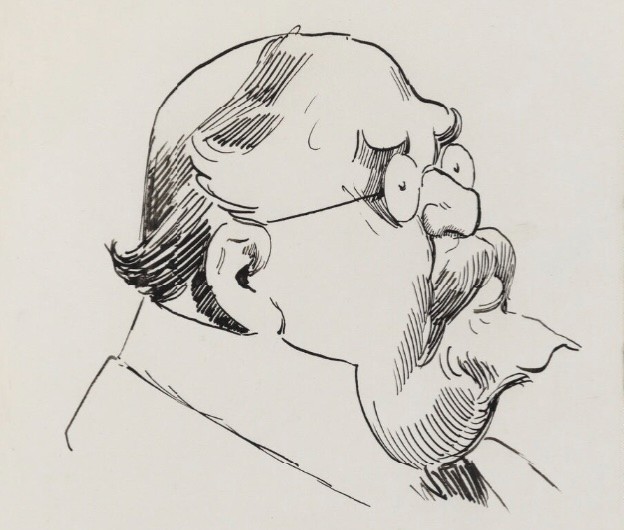

Not a great deal is known of his early life. Some of the evidence is contradictory. His gravestone says he came into the world in Prestbury, Cheshire, his birth certificate that he was born in Stafford, in 1846, to James Wright, a Methodist minister, and Matilda Wright, née Whitaker, the daughter of a Macclesfield tailor. He was christened James after his father, but this was later dropped: ‘Whitaker Wright’ offered an altogether more impressive ring.

By the time of the 1871 census, Matilda had become a widow. She appears as a grocer, in Birmingham, but there is no mention of her son. The printing business he had established with his brother, JJ, in 1868, had gone bankrupt and so they had emigrated to Toronto, where James set up as a commercial traveller.

By 1873, James had moved to Pennsylvania, where he embarked on his natural calling: promoting deals in fledgling companies to unsuspecting investors. Not all were everything they were cracked up to be, but James professed a training in inorganic chemistry (provenance unclear), and he used this veneer of expertise to embark on a career as an assayer.[19]

Assaying provided an entry for speculating in undeveloped mines and, although he started with just a few dollars, Whitaker Wright says he soon found he ‘was dealing in amounts that made a profit worthwhile.’ Sir Richard Muir – who, as Whitaker Wright’s defence counsel, got to know him well – claims that, by 1877, he was already a millionaire. It was, he says, an eventful life:

Once, while prospecting in Idaho, near the Snake River, where the Indians were on the war path, an Indian and his wife pitched their tents near his hut and he paid them a call. He gave the woman a plug of tobacco, an act which probably saved his life, for shortly afterwards a war party of Indians came to his shanty to kill him, but the squaw who had received the tobacco induced them to leave. They proceeded down the river, and massacred three of Whitaker Wright’s men.

It’s a ‘charming’ story and, true or not, it’s the sort of thing that helped to build up the Whitaker Wright mystique – the prospector who rolled up his sleeves and took significant risks to build his fortune.

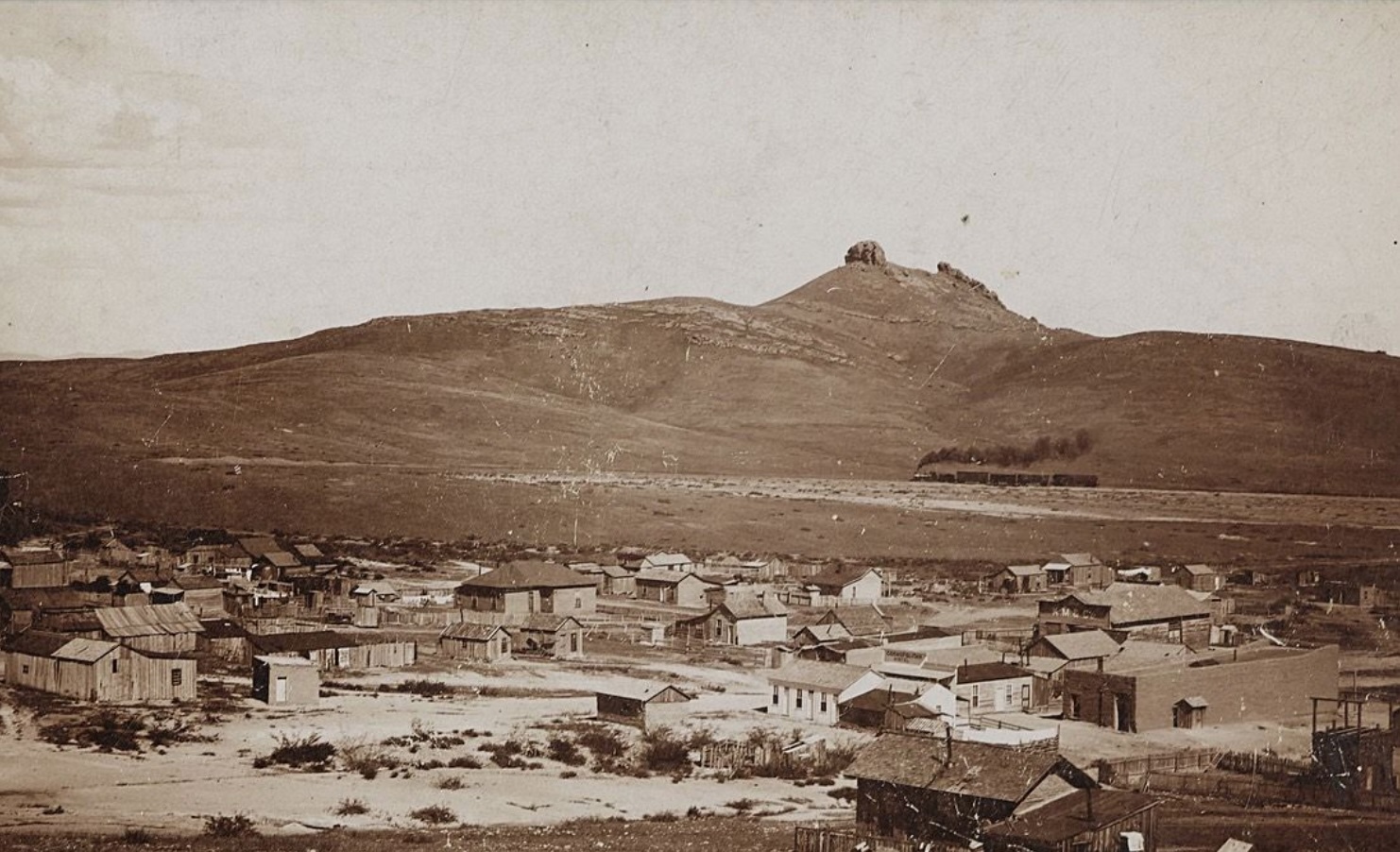

By the turn of the next decade, WW (as he came to refer to himself) had moved to Leadville, Colorado, then in the middle of a silver boom. Oscar Wilde, who visited in 1882, referred to it as the roughest city in the world, as well as the richest. Its men, every one of them miners, all carried a revolver:

… so I lectured them on the Ethics of Art. I read them passages from the autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini and they seemed much delighted. I was reproved by my hearers for not having brought him with me. I explained that he had been dead for some little time which elicited the enquiry ‘Who shot him?’ They afterwards took me to a dancing saloon where I saw the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across. Over the piano was printed a notice: ‘Please do not shoot the pianist. He is doing his best.’ The mortality among pianists in that place is marvellous …[20]

At Leadville, WW bought the Denver City mine, merged it with some other properties, and floated the Denver City Consolidated Silver Mining Company. The owner of a next-door property was George D Roberts, an arch promoter and manipulator of mining shares. In 1872, he had been involved in what became known as the ‘Great Diamond Hoax,’ a scheme hatched by two Kentucky grifters who acquired some uncut diamonds, mixed them with garnets, rubies and sapphires and, through Roberts, spread the word of a significant new field which they had discovered in Indian territory. Roberts involved William Ralston, founder of the Bank of California, and, through him, the jeweller Charles Tiffany. When the scheme unravelled, the San Francisco Chronicle had called it ‘the most gigantic and barefaced swindle of the age.’

Despite these events, when they met, Roberts still stood as the successful sponsor of over a dozen mining companies, in Colorado, Nevada, California and Mexico. Combined, they were worth some $120 million. WW seized his opportunity and asked Roberts to teach him a few tricks.

The foremost of these, later to become so neatly suited to the involvement of Lord Dufferin, was to entice a respected luminary to become the officer of and/or the investor in, a fledgling company. In 1880, WW persuaded Edward Drinker Cope, a wealthy, eminent palaeontologist, who brought the respectability of the US Geological Survey and the editorship of the American Naturalist, to became Denver City Consolidated’s treasurer. In March of that year, the company floated on the exchanges for $5 million. It never made a profit.[21]

Needless to say, by the time the true quality of Denver City Consolidated had been revealed, WW had moved on, first to Utah, then to Philadelphia, where he promoted the Colorado Coal and Iron Company and, in conjunction with Roberts, the Sierra Grande Silver Mining Company, with assets in New Mexico’s Lake Valley.

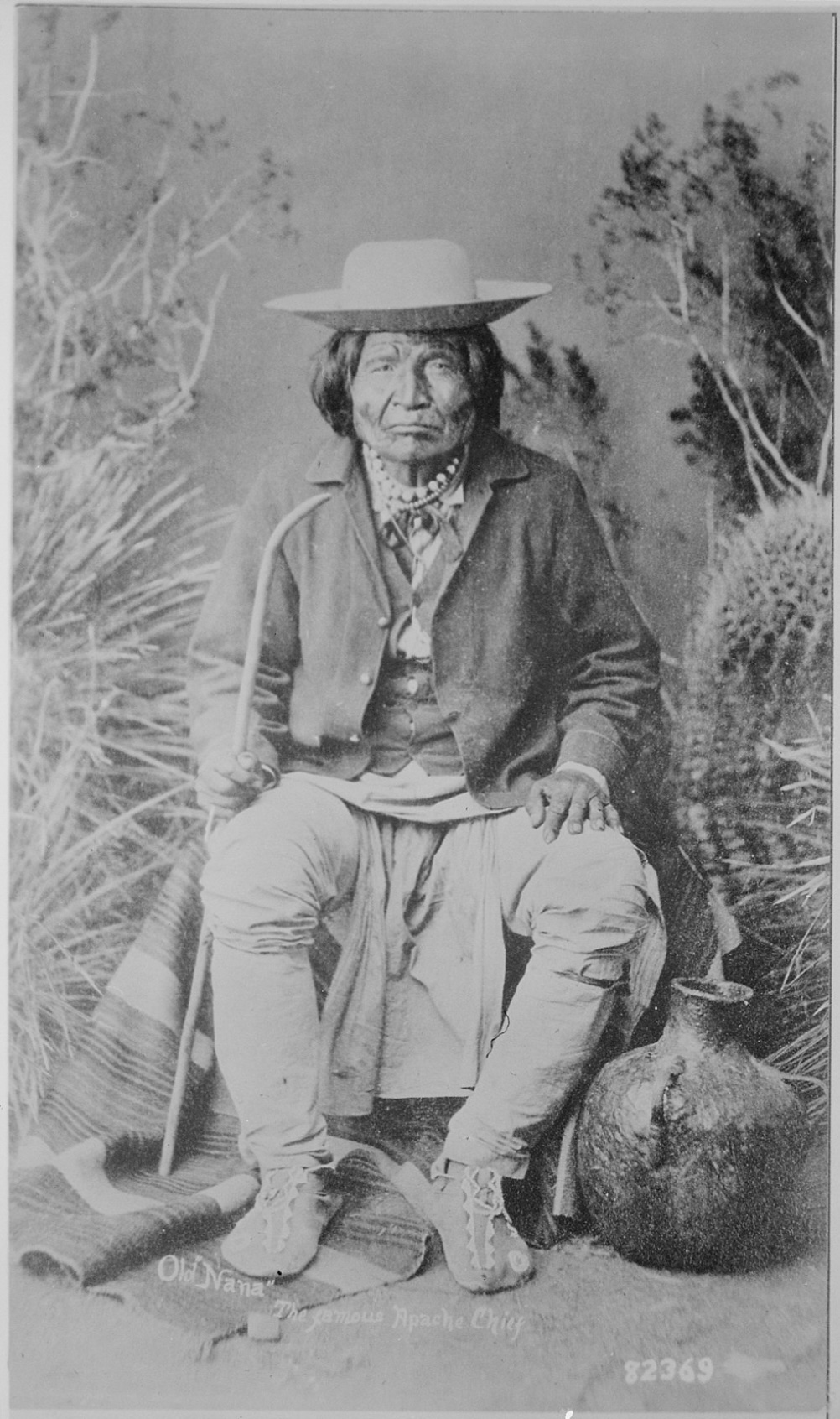

The last had something of the Snake Valley about it, for the Apaches were giving trouble and, in a raid in 1881, they killed George Daly, the mine’s manager.

Daly had first encountered WW at Leadville, where he operated as a ‘shotgun miner’, someone to whom mine owners could turn to intimidate their workers, or the owners of neighbouring mines. He left under a cloud, in February 1881, after an outbreak of violence at the nearby Robinson mine, in which he was heavily implicated. A printer by trade, he had no mining qualifications. Even so, in the Denver City Consolidated Prospectus he claimed the title of ‘Mining Engineer’ when he offered an appraisal of its assets, venturing the opinion that they would prove ‘as valuable and productive as any mines in this State.’

When the Apache chief, Nana, launched his attack on Lake Valley, the following August, the headstrong Daly over-ruled the cavalry commander at Fort Cummings and set off in pursuit. He led his posse of twenty miners into an ambush and was killed during a six-hour battle, along with four soldiers and another miner. The Homer Mining Index, a Californian mining weekly, clearly believed that, by getting rid of George Daly, Chief Nana had done the world a significant favour. He was, it declared, ‘one of the most despicable of characters.’ Just a year before, one of its correspondents had characterised him as ‘a toady by nature, a scrub by instinct and a bully on general principles:’

His success shows what a man can obtain by sycophancy, cheek and a willingness to do any sort of dirty work for his masters. If he had been anything but the creeping, malicious bug-sucker that he was, the respectable citizens of Bodie would never have let him be run out of town … He knows no more about a mine than a pig does about a blow-pipe – and if he had not accidentally fallen in with men who needed his debased services, he would naturally become a pimp or barkeeper in a cellar dive.

Lake Valley had been discovered accidentally, in 1878, by a cowboy prospector, George Lufkin, who happened across an unusual piece of rock and had the wit to have it assayed. It ran several thousand ounces of silver to the ton. Unfortunately, Lufkin’s capital, or his patience, ran out before the mine’s richest ore body was discovered. (He sold his interest for just $10.50.) The ‘Bridal Chamber’ was discovered by John Leavitt, who sold it to Sierra Grande for a few thousand dollars. Over the course its life, seven sets of workings were operated by Sierra Grande. Combined, they produced 5 million ounces of silver, and of this the Bridal Chamber contributed half.

WW recalled that he had been ready to give up on the Valley at the time of Daly’s death:

I was on my way back to the mines at that time and was given an account by my friend, General ‘Phil’ Sheridan. Meanwhile the work at the mines had been continued under the direction of a foreman and, just as the body of my superintendent was being brought into his bungalow in the camp, a body of ore was penetrated which ran $10,000 to the ton, and enabled us to pay dividends of $100,000 a month for a long time. [22]

Immediately, WW and Roberts employed Cope to spread the word. When he first visited Lake Valley, in early August 1881, he wrote to his wife of his concern that the Apaches were making it ‘hot’. He left two weeks before Nana’s attack, however, evincing misplaced confidence that Daly was ‘an old Indian fighter’ who knew how to manage them. More to the point, he was persuaded that the valley was ‘a great mining region, perhaps the best in the entire West.’ No doubt, it helped that Cope used his authority to argue that the fossils in Lake Valley’s limestone showed it was of similar age to the great silver mining areas of northern Mexico. He soon appeared in the Sierra Grande prospectus as a director.

Next, Benjamin Silliman, a professor of chemistry at Yale, was recruited to the cause. Like Cope, he had a blemished reputation: in 1873, an attempt had been made to expel him from the National Academy of Science, after his reports on the Emma mine, in Utah, had proved hopelessly optimistic. Perhaps for this reason, he was careful to qualify his judgements. Even so, on 9 June, a despatch was sent to the New York Tribune, reporting that ‘Professor Silliman, the eminent mineralogist of Yale College, has today estimated the ore in one mine and piled on the dump at 5,000 tons of an average assay value of 100 ounces, and the sacked ore in the storehouse at 250 tons, averaging 1,000 ounces.’ By 15 July, the Mining World paper in Las Vegas, New Mexico, was expressing confidence that there was ‘in the Lake Valley mines a marvel of wealth which neither California nor Nevada ever approached.’[23]

Silliman’s full report on the mines of southern New Mexico was published in Engineering and Mining Journal, on 14 and 21 October 1882. In respect of Lake Valley, he remained careful in his choice of words. On the one hand, he wrote, the mines belonged to ‘the same category with the Leadville … and other deposits in the older limestone formations.’ This meant they were not ‘fissure-veins’, of the type universally deemed to offer the greatest value and permanence. On the other hand, fissure ‘bonanzas’ were the ‘rare exception’:

At Lake Valley, the ores are of exceptionally high tenure in silver, and, compared with Leadville … are low in lead. In the simplicity of their mineralogy and metallurgy, the Lake Valley ores … are exceptional. It remains to be seen whether, on deeper exploration, these conditions remain unchanged.

Despite the final qualification, WW and Roberts had been given all that they needed to pump their story. And, in fact, in one certain respect, the Bridal Chamber was an extraordinary deposit. As the New York Tribune had been informed in the 9 June despatch, it was ‘so rich and porous that, at many points, a candle-flame will melt it into silver globules.’ WW’s own Mining Journal referred to a report in the San Francisco Daily Exchange that Colonel Osbiston was sufficiently impressed that he ‘offered to give $500,000 for working the claims for thirty days.’ Beyond that, the Sierra Grande prospectus claimed there were 144 million in silver ore ‘in sight’. The term was carefully chosen. It suggested proven reserves but, in a legal sense, it was the expression of an opinion rather than a statement of fact.

Not everyone was taken in by these claims. To start with, the San Francisco Daily Exchange printed a riposte to the Mining Journal’s report about Colonel Osbiston. It turned out that he had made no such offer. On the contrary, he had noticed that many of the holes drilled into the chamber’s seam had been kept shallow, ‘for fear … of running through the vein and exposing its weakness.’ On 20 July 1882, the paper warned,

Seriously speaking, anecdotes about bridal chambers, silver lakes, globules, high assay reads, $144,000,000 in sight, cellars stocked with sacks of ore etc., while pleasant to read, will not, in this matter of fact age, draw ducats into mining stocks.

For its part, on 15 July, the Engineering and Mining Journal, commented,

While Professor Silliman’s standing as a scientist and investigator is above all question, his record as an expert in the examination of mines is such as to make it necessary to receive his estimates with extreme caution … With a report by Professor Silliman, and with George D Roberts really, though not officially, at the helm, we must warn investors not to touch the stock.[24]

The problem with Lake Valley was that, although it contained scattered pockets of very rich ore, they did not combine into a continuous body that could sustain long-term development. For five months, the Sierra Grande Mining Company paid handsome dividends. By April 1883, however, visits to the mine were stopped, as its output had slowed. In March, the company announced it would be paying dividends quarterly rather than monthly. Inevitably, however, WW and Roberts had disinvested long before the ore ran out.

As it turned out, Roberts did rather better than WW, because he sold out to him, as the output of the mine started to decline. Cope fared the worst of all. His losses were so severe that he was forced to sell his home and most of his celebrated collection of fossils, to the American Museum of Natural History. In 1883, he led the campaign to have the ‘swindler’ Whitaker Wright removed from the company’s board. By the end, he had lost most of the $500,000 he had inherited from his father.[25]

For his part, WW returned to Philadelphia more than whole. There, he launched the Colorado-based Security, Land, Mining and Improvement Company, and joined the board of the Penn Conduit Company, which was modernising Philadelphia’s sewerage system. He promoted further mining ventures in Nevada’s Grass Valley and became a member of both the American Institute of Mining Engineers and the Consolidated Stock Exchange of New York. With Anna Weightman, his wife since May 1878, he settled down to nurture a young family of three in a grand colonial-style property near Philadelphia’s Haverford College.

Then he ran out of luck. The 1912 supplement to the Dictionary of National Biography informs us that ‘he had resolved to retire from business’ but that ‘his American career ended disastrously, owing to the failure of the Gunnison Iron and Coal Company, in which he was largely involved, and the great depreciation in other securities.’

This was in 1889, a bad year for markets. But there was more to it than that. Various claims that he had misappropriated funds necessitated a prompt return to England. Despite them, WW escaped with a good portion of his wealth and his reputation intact. Before long, he had successfully listed some Mexican and Australian silver and gold mining operations on the London Stock Exchange. He began to assemble the components of the estate which was to become his own version of Clandeboye.[26]

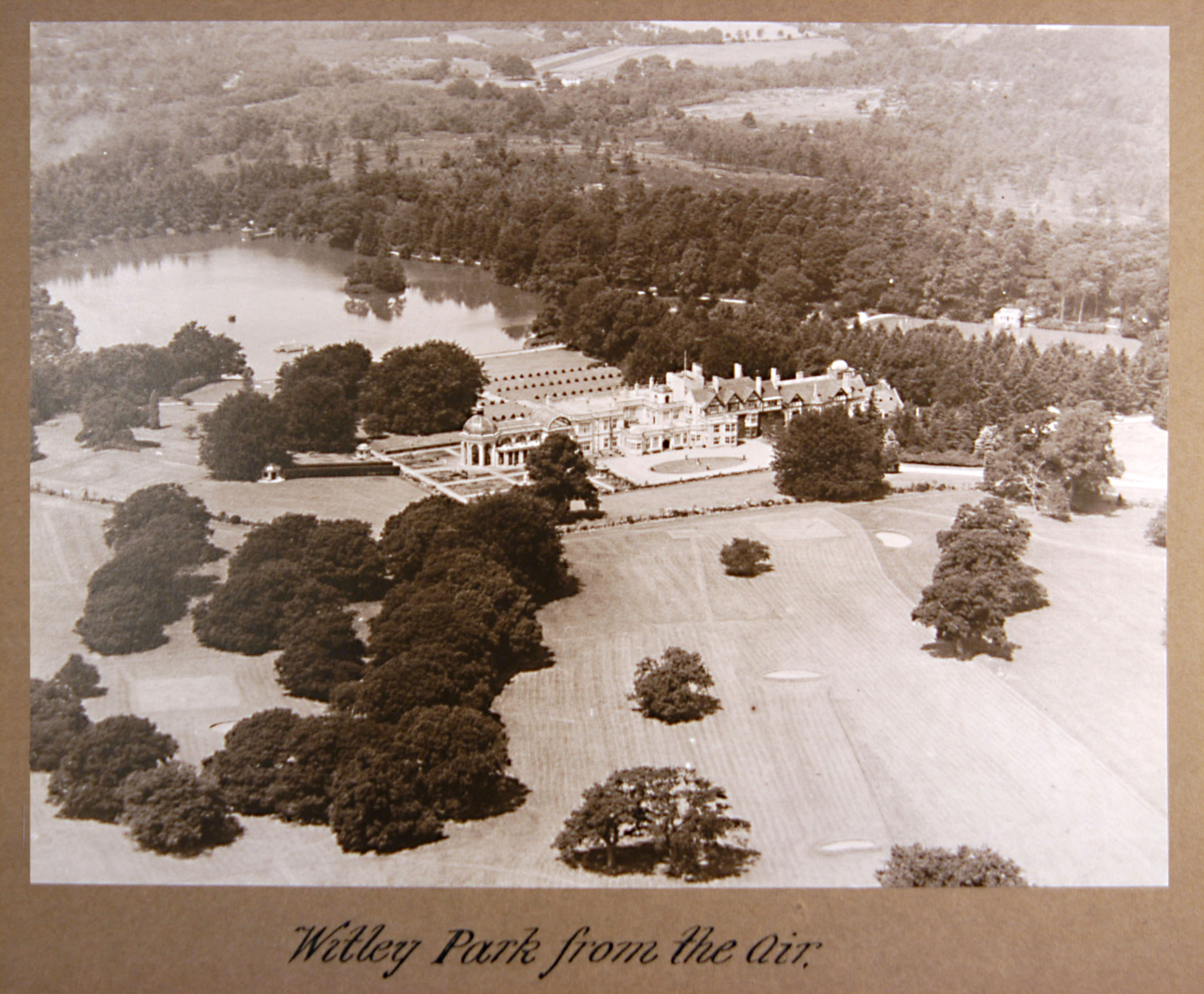

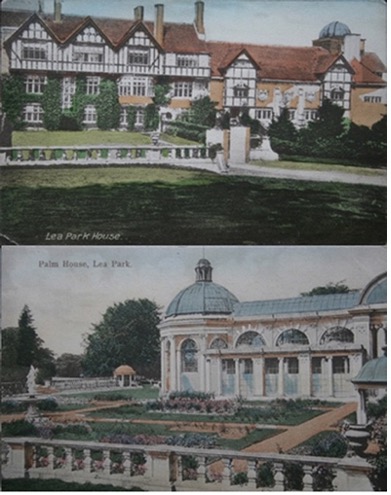

In 1890, he acquired a farm near Lea Park in Surrey, from the Earl of Derby. In 1894, he bought Lea Park House from WH Stone, a former MP for Portsmouth and, by 1897, he had added the manor of Witley and the estate of Lea Park and was embarking on a series of extravagant embellishments. . To the original manor house Whitaker Wright added two new wings, one containing an observatory, the other a palm house. It is said that, at one point, there were six hundred men working on the house alone and that craftsmen brought from Italy took two and a half years to carry out the carvings in a single room.

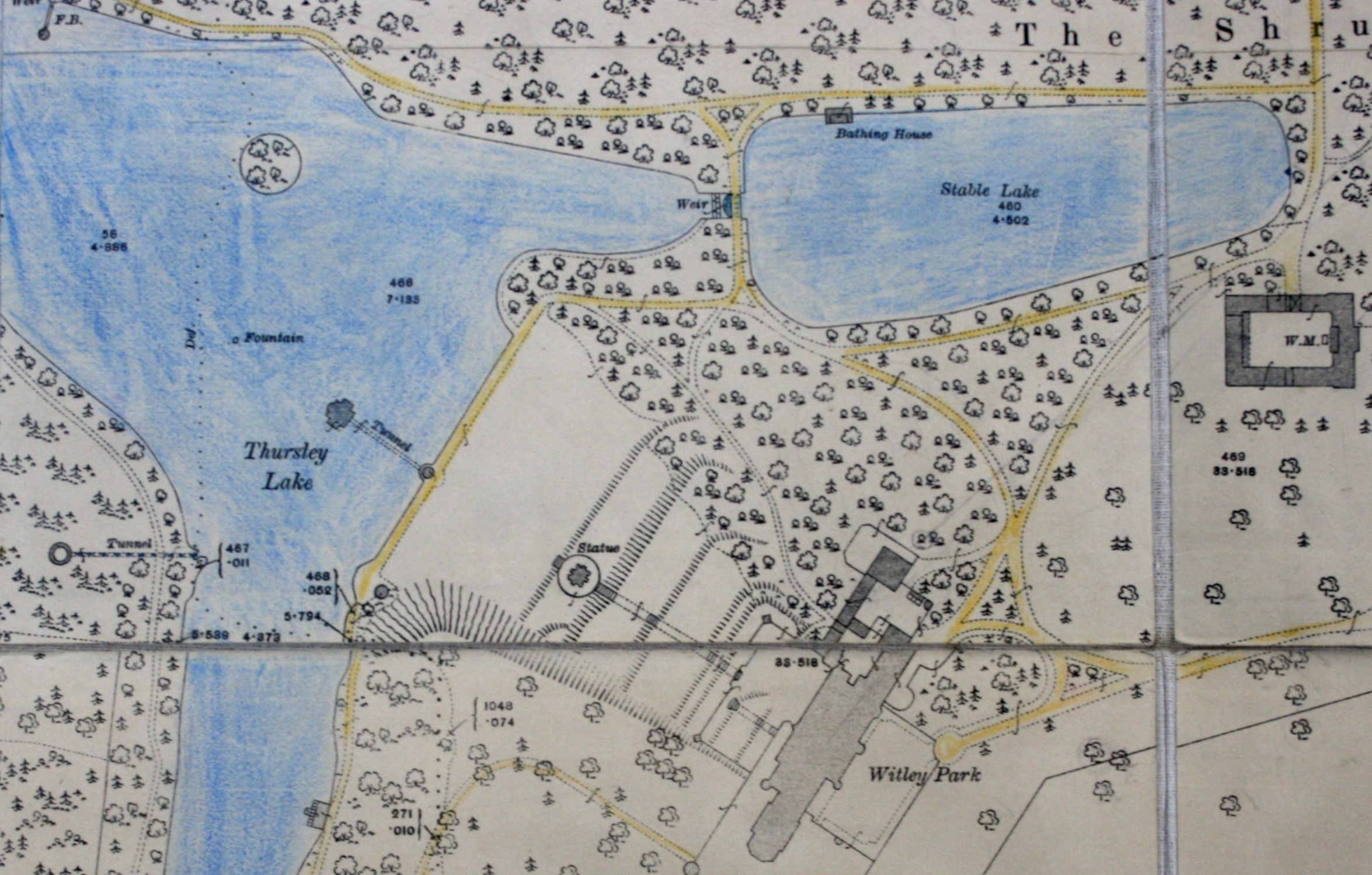

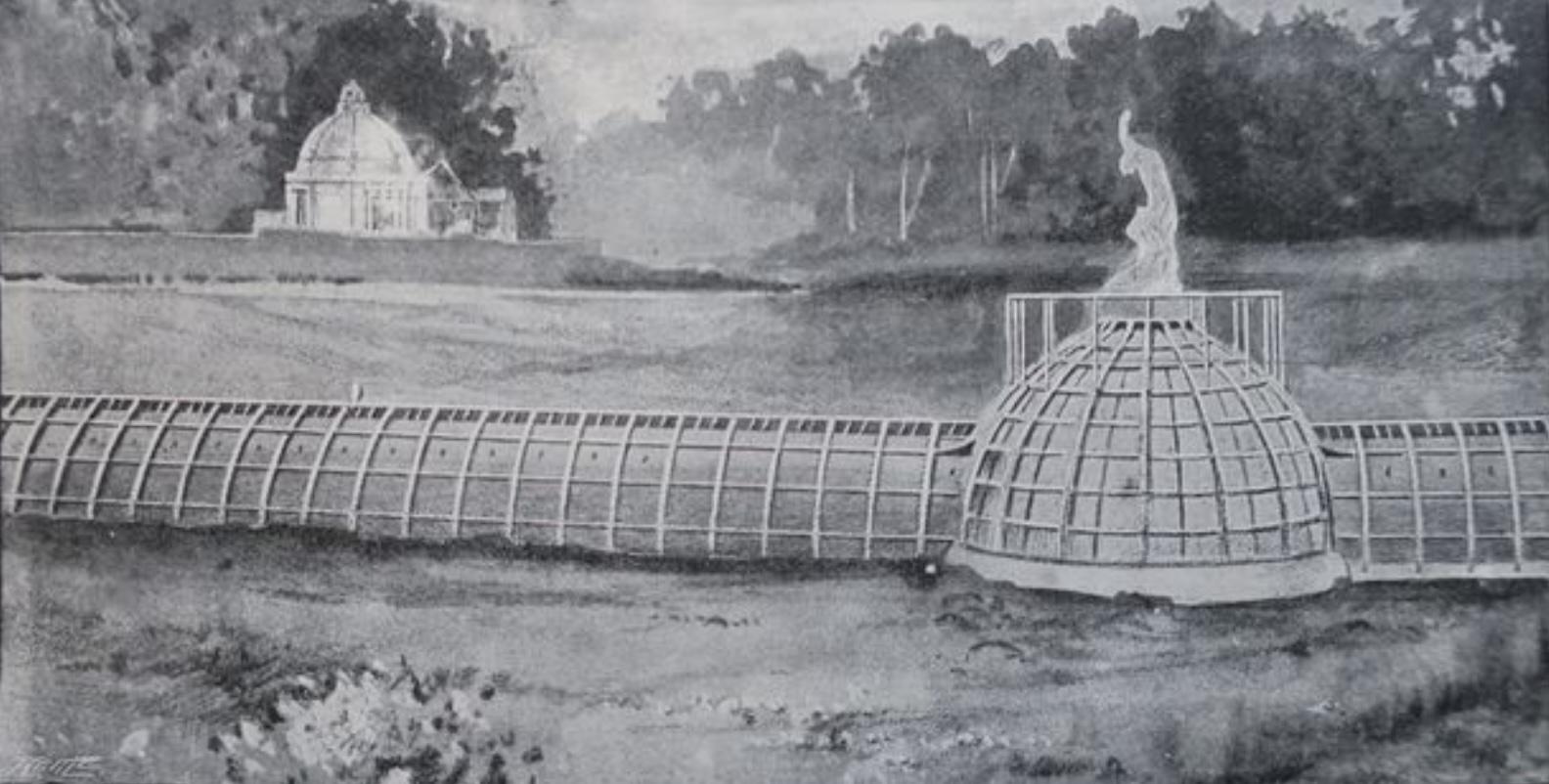

In the grounds, which were enclosed by an eight-foot-high wall about four miles long, advantage was made of the Brook stream to create three artificial lakes – a process that necessitated the re-siting of some low hills which blocked the view from the house, and the labour of a further three thousand men. The lakes covered an area of over twenty-five acres and were on three levels, with the largest (and lowest) being between the other two. This meant that the flow of water from the Upper Lake was piped through a four-foot diameter steel pipe that extended for about a thousand yards along the Thursley Lake shore, before debouching into the Stable Lake through the mouth of a huge ornamental dolphin. The water that flowed from the Thursley Lake was then pumped back to the Upper Lake using a specially installed turbine.

Whitaker Wright had spotted the dolphin in Italy. He shipped it to the south coast only to be told that there were no railway wagons large enough to transport it. Undaunted, he used his own traction engines to haul the monster to his estate. The story goes that it was so vast that it would not fit beneath one of the railway bridges crossing the way, and that the road had to be dug out to get it through.

Some other statues in Carrara marble, now known as ‘The Naked Ladies’ of York House, in Twickenham, and thought variously to portray a group at the birth of Venus, or some naiads or Oceanids, were also acquired, probably to decorate the cascade between the Stable Lake and Thursley Lake. They were never installed, as they were said by the York House contractor still to be in their packing cases when he came to collect them, in 1906. Since several of them weighed over five tons, deploying them would have been no easy task.

A boathouse and a bathing pavilion, designed (as early commissions) by Edwin Lutyens, were added to the estate, but the piece de resistance, for which Witley Park became best known, was the ‘submerged room’ under the Thursley Lake. It was approached through a tunnel and had an anteroom ‘with glass skylights like giant portholes,’ which gave access to a platform above, offering a view of the house. Between the platform and the lake shore, as if emerging from its waters, a statue of Venus added to the beauty of the scene. In fact, it was attached to the top of the dome and served as a vent for the circulation of air below.

The room is not actually that big, but its scale was magnified by reputation to that of a ballroom, where dancers could pause for breath and look up at the carp that had been observing their pirouettes. The fish were said to have been specially imported from Azay le Rideau and the glass panels in the dome were reportedly three inches thick.[27]

How could all this be afforded? The answer was that Whitaker Wright was riding the explosion in mining stocks on the London stock exchange. (In the early 1890s, there were as many as eight hundred listings.) Investors were excited but confused. They needed an ‘old hand’ to guide them, and Whitaker Wright was happy to supply the role.

His first forays were the Abaris Mining Corporation (1891), the West Australian Exploring and Finance Corporation (1894) and the London and Globe Finance Corporation (1895). In March 1897, these were merged into the ‘New Globe’, which spawned companies of its own: the British and American Corporation, of 1897, and the Standard Exploration Company, of early 1898.[28]

Shortly after the British American flotation, Dufferin spoke, at a meeting of shareholders, powerfully in the company’s favour, citing at the end of his speech, the opinion of the former Lieutenant-Governor of the North West Territories of Canada (a board member) that it ‘holds the key to the majority of the golden treasure houses of British Columbia.’ His speech was greeted with loud applause, but it did not convince The Economist. The paper reminded its readers that the company had ‘widely advertised its prospectus just about a month ago, though the £1,500,000 of capital asked for was only to be accepted from shareholders in the London and Globe Finance Corporation.’ The capital was to be applied for the purpose of acquiring new properties, but the newspaper puzzled why this could not have been achieved ‘more economically and effectively’ by an issue of capital by London and Globe itself:

Two explanations have been hazarded; one that the underwriting and financing of the new Corporation was intended to provide a profit out of the pockets of London and Globe shareholders, to inflate the profit and loss of that company, and to increase the sum available for distribution; the other that two sets of fees for largely identical boards are better than one set. Neither explanation, however, is conclusive, and we can only regard the inception of the British America Corporation as a conundrum which it is better to give up.

The Economist also noted that two of the properties to be acquired were the Le Roi mine at Red Mountain (said to be paying dividends of £10,000 per month) and the Alaska Commercial Company. It added,

Most other directors, even in this case-hardened age, [it added] would be just a little disconcerted in having to inform a body of shareholders that, of the principal purposes for which their capital had been invited, one had been definitely abandoned, and another was still in the stage of negotiation.

This was not the limit of the Economist’s criticisms. It continued to state that,

In the few public appearances which Lord Dufferin has made in his new capacity of financier he has shown a disposition to deal lightly with hard facts and figures, mainly leaving them to his colleagues; but, like the skilled diplomatist that he is, he has displayed conspicuous ability in making rough places plain, and in glossing over apparently difficult points in such a way as to impress the average shareholder with the conviction that things are really much better than they look, and that ‘everything is for the best in the best of all possible’ enterprises. [29]

For as long as the market was rising, WW could do no wrong, and Dufferin was happy to follow on his coat tails. In September 1899, New Globe reported profits of £483,000 and a cash balance of £534,455. Dufferin, in a speech written by WW, declared it powerful evidence of its prosperity. In the following year, the profits were £463,272. The cash balance had fallen to £113,671, but the company boasted investments in sundry companies worth £2,332,632 – a figure which the Board declared to be a conservative estimate, which factored in an extra provision of £1 million for possible depreciation, in which holdings had been marked down to ‘as low a level as possible.’

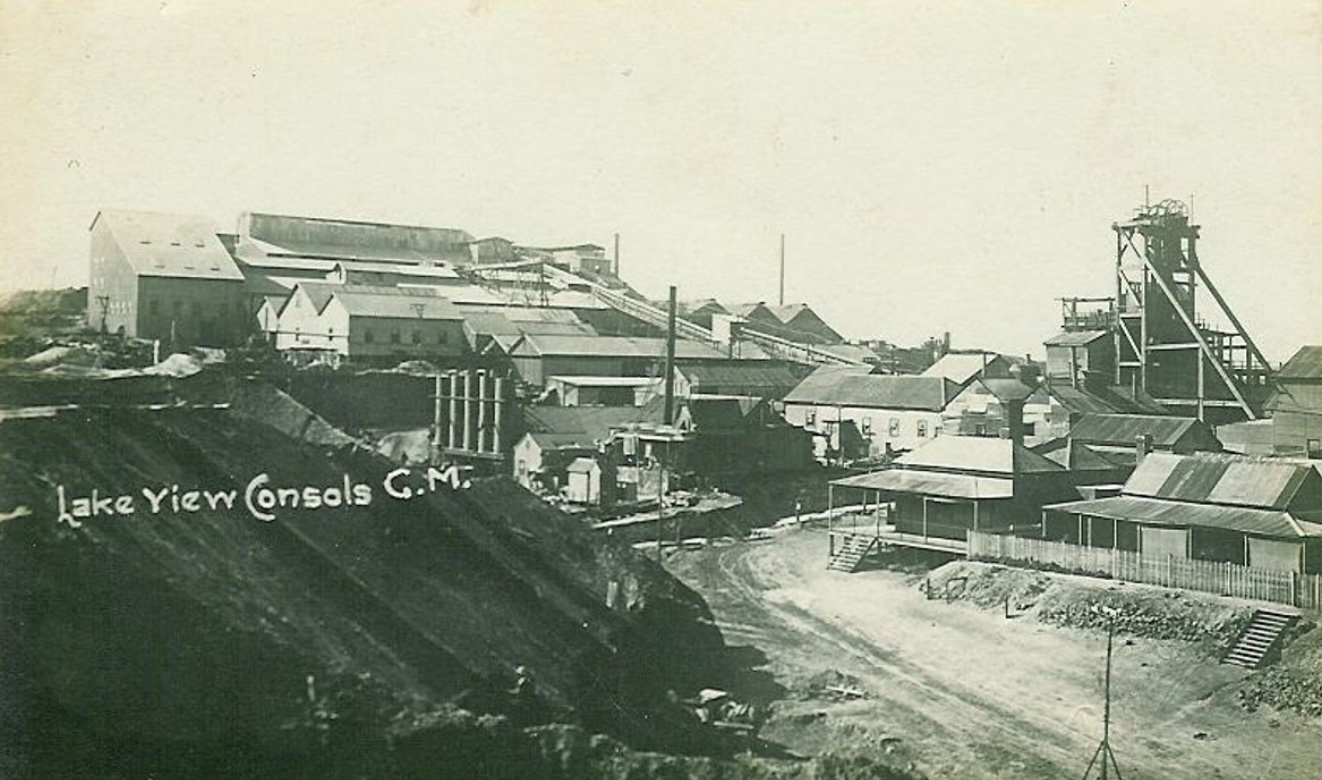

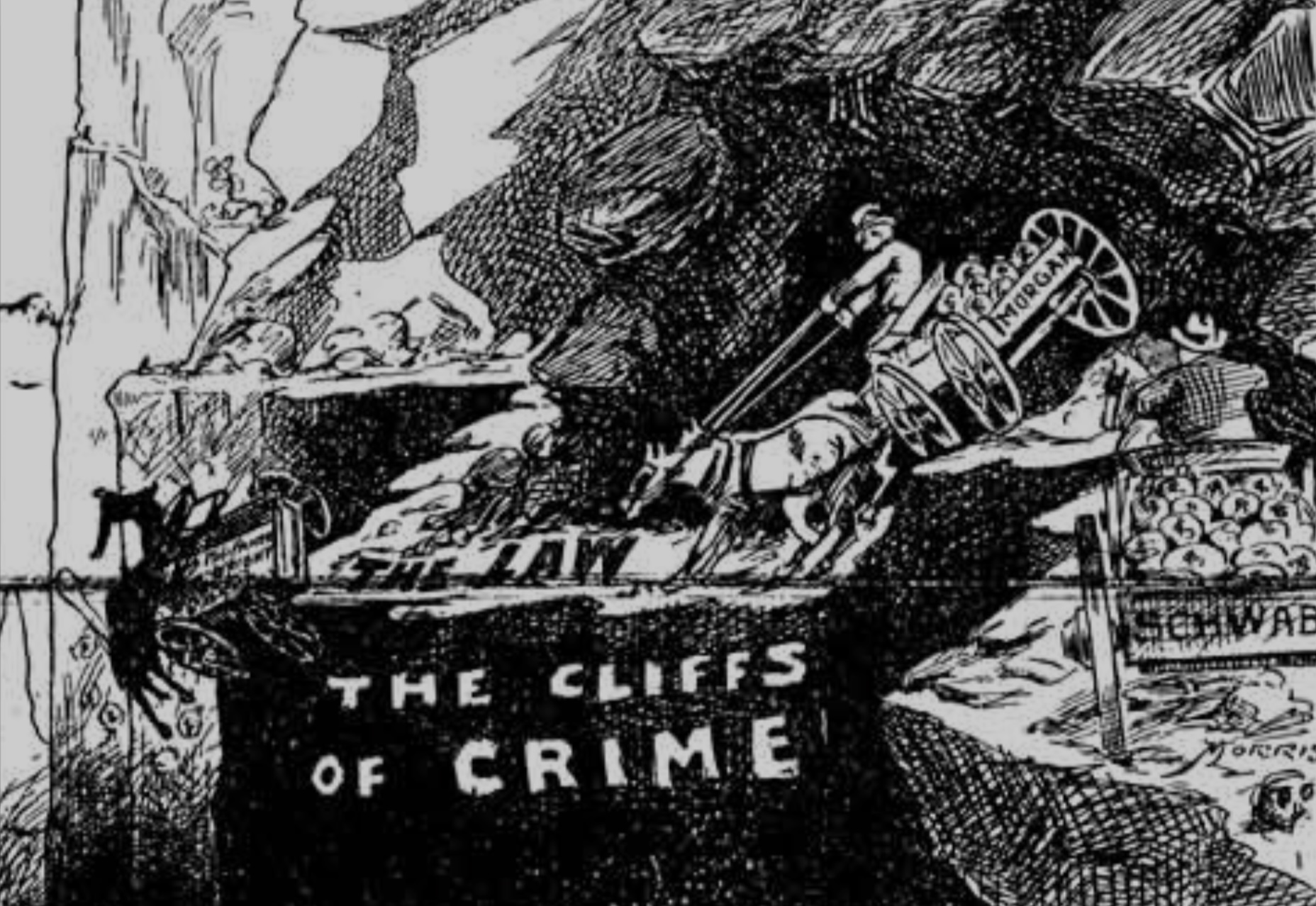

That was at the AGM on 17 December 1900. Just ten days later, the New Globe collapsed, taking with it no fewer than thirteen firms on the stock exchange. It was a sensation. As The Times rather laconically put it, ‘the last settlement of the century has certainly terminated in a deplorable manner.’ The immediate cause for the collapse was a battle over New Globe’s Australian subsidiary, Lake View Consols.

The Collapse of London & Globe

In 1896, when the Jameson Raid punctured the valuations attached to South African mines, attention had switched to properties in Western Australia. By the autumn, there were 260 securities traded in the ‘Westralian market’, offering names such as ‘Bird-in-Hand’, ‘Empress of Coolgardie’ and ‘Nil Desperandum’.

As The Economist complained, there was much that was murky in the way these companies were presented to the public. Not least, it declared, it was ‘impossible to trace the operation from the local-vendor stage to the utterly disproportionate basis upon which investors are asked to subscribe.’ Some promoters were even more unscrupulous than WW. Horatio Bottomley, champion of the publisher Hansard Union, which crashed, in 1889, amidst charges of swindling, promoted some twenty Westralians between 1893 and 1897. Only one lasted more than a few years, because he and the other vendors held back the lion’s share of subscriptions. By 1900, Bottomley’s reputation had been much deflated, although it was not until 1922 that he was convicted of fraud and sent to Wormwood Scrubs.[30]

Like Bottomley’s, most of WW’s assets in Kalgoorlie had little to recommend them. The edifice was kept going by two operations with merit, Ivanhoe and Lake View. In early 1899, a peaking in production and the onset of the Boer War caused Lake View’s shares to tumble. Acting on advice from the mine’s manager that a new seam had been discovered, WW used the opportunity to buy up stock. For a while, the share price rose, but then the seam became depleted, and the bears stepped in.

At the AGM, on 17 December 1900, Whitaker Wright spoke of ‘cycles in finance’ during which ‘you might as well attempt to dam a river with a bar of sand as to stop depreciation.’ A ‘clique’, he reported, were trying to mark down the shares, but they were not selling them, ‘and one of these days you will see a reaction which will carry them up to where they belong.’ Lord Dufferin paid tribute. ‘Never,’ he declared, ‘have I seen any man so devote himself, at the risk of his health, and at the risk of everything that a man can give to business of the kind, as Mr. Whitaker Wright.’

Whitaker Wright kept buying, as did New Globe and Standard Exploration, until 28 December. The following day, under the title ‘City Notes, Woeful Australians,’ the Pall Mall Gazette reported,

The scene in Throgmorton Street last night will become historic. The West Australian market, weak in the ‘House’ at the close, quickly developed symptoms of something much worse than the slump. Round Lake Views the keenest anxiety centred. From 10 the shares were offered down to 8, with no apparent reason to account for it. Then, with white faces, the brokers came flying back from their banks with the news that the cheques of four-five-six firms had been returned to the payees! All the returned cheques emanated from firms closely connected with the London Globe division. One of them, the news of whose trouble caused the greatest astonishment, was a firm of old-fashioned brokers, whose name has been to conjure with for solidity.[31]

By the evening of 31 December, the same newspaper was reporting that, ‘the collapse of the Globe Finance group, involving the failure on Saturday of no fewer than thirteen firms on the Stock Exchange, is one of the most serious disasters of recent times for that institution.’ The brokers had bought shares for WW in the mistaken belief that he was backed by a powerful syndicate that would settle on their behalf. In fact, although the syndicate had supplied Globe with almost half a million pounds to tie it over at mid-month, it had made no such commitment for the end of the year. (In June 1902, the Globe lost in its attempt to prove its case in court.)[32]

Part of the problem was that New Globe had tied up capital in the development of the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, later London’s Bakerloo Line. Had New Globe survived, it may have proved one of WW’s better investments, but Globe needed the cash, and he was unable to extract it in time.

It is possible, however, that WW was also the victim of a sting at Lake View, in which the manager of the mine was complicit. According to the biographer of WW’s defence counsel, WW reported at his trial that, in the autumn of 1899, the directors of the Globe had been advised that Lake View could sustain its monthly output of 30,000 ounces of gold ‘indefinitely’. On the strength of this, he decided to get control of all the shares he could, borrowing the necessary funds from his allied companies, as most of Globe’s cash was locked up in the Bakerloo line. ‘Then, suddenly, with practically no warning, output at Lake View dropped to 10,000 ounces a month and the shares which he had bought at £23 dropped to less than £10.’

So far as it goes, WW’s defence ignores the implication that he was acting on inside information, to the detriment of other shareholders. But the interest does not stop there. WW’s biographer, Henry Macrory, suggests that Lake View’s manager, Henry Clay Callahan, had been in league with an American mining magnate, Henry Bratnober, and had deliberately exaggerated the size of a new ore find (the ‘Duck Pond’) in order to drive the shares up and avail Bratnober a profit. According to this account, Bratnober may have made £1,000,000 from the ramp in the shares. He exited before the bubble burst, but WW was not alerted as to the true state of affairs. He did not.

Not all the explanations for WW’s bust are consistent with each other, however. Another source agrees that, in 1898, misleading statements were being made about the mine, but it makes no mention of Callahan or Bratnober. According to this account, in 1901 (following Globe’s collapse), the chief engineer, GWW McKinnon, was dismissed for having colluded with share speculators to drive the share price down. The mine’s manager, a Mr. Hartmann, was accused by McKinnon of falsifying ore reserves and poor cost control. He was also criticised by the board for ‘gutting’ the mine and investing nothing in exploration. (In 1902, Hartmann was replaced by the London firm, Berwick, Moreing & Co., whose experts advised, correctly, that rich ore lay at depth.)

A third account of Lake View’s bust was proposed by the Australian politician, Randolph Bedford, in 1944. Bedford begins with the claim that, by way of an incentive for action that would counter the bears, WW promised Callahan the profit on a holding of two thousand shares if he shipped quantities of the ‘Duck Pond’ ore to be smelted in Eastern Australia. When it showed signs of depleting, Callahan was summoned to London to explain what was happening. His shares at the time were worth £22,000. According to Bedford, he obtained his paper profit at the point of a revolver, which he used to detain WW until a cheque was cleared by the bank. Then the bear market resumed, as the mine’s fundamentals reasserted themselves.

Perhaps Bedford’s more substantial claim is that WW had the support of the Rothschilds and that it was their withdrawal which destroyed him. For a while, the bears believed that WW was acting in concert with them. Then WW called one of the more significant of them, a personal friend, aside and, in an attempt to persuade him to switch course, informed him of the Rothschilds’ backing. The friend refused to abandon his associates and, instead, informed the Rothschilds of the true state of the mine.

That smashed Whittaker Wright. The Million Pound syndicate followed him down in his fall, striking at him as a vulture might strike a crippled hawk. They sold Lake Views down to £11, and continued their bear during the agreement, and even sold the shares lodged with them by Wright for security. At £11 they bought in and tendered 40,000 shares to Whittaker Wright. He failed to pay, and the Million Pound syndicate became, against their will, the controllers of Lake View. They smashed Whittaker Wright, thinking him stronger than he really was, and hoping for good pickings from the corpse, but, smashing him, they smashed themselves. [33]

Perhaps the most obvious thing to be said is that, at its end, there was no shortage of manipulation in Lake View shares. Which does not quite excuse Lord Dufferin’s remark, at a meeting of shareholders, on 9 January 1901, that he knew little about what was going on and, indeed, little about finance at all.

To the last, he complained that he had been betrayed. In one letter to his financial adviser, he complained,

Things were going quite well with us until lately, and then in a single day Mr WW embarked on a giant gamble on the Stock Exchange without saying a word to any of us and has … in fact ruined us.

Unfortunately, although standards in 1900 were a little different to today, this will not quite do. A year earlier, Dufferin had received from Lord Loch a frantic note in which he revealed that, to deal with the bears, WW had raised upwards of two million. Loch had declared that WW ‘had pledged everything he had!’ So, for a year, Dufferin was aware of the risk to which the company was exposed. It seems he did very little about it. Even on 16 January 1901, he spoke of those who had ‘betrayed WW.’ (Lord Loch died in the preceding June.)[34]

At the January meeting, Whitaker Wright proposed a scheme of reconstruction, which failed to pass. However, he did persuade the shareholders to accept a voluntary liquidation. The advantage of this was that it avoided the need for external scrutiny of the directors’ actions. Not everyone was convinced of the justice of his approach. The Times, for one, was hostile. It wrote,

We do not believe that the real interest of creditors, shareholders or the public will be served by allowing Whitaker Wright to raise five shillings, or any other sum per share, and continue to carry on this moribund and mischievous concern.

Then, over the summer, the London and Globe, the British and American, Standard Exploration and the Le Roi went into compulsory liquidation. The losses were huge. Five years later, the receiver reported that, even after its assets had been liquidated, the London and Globe still owed £2.4 million. Eventually, in December 1901, the order was issued for a receiver’s examination.

When confronted, Whitaker Wright objected strongly to the suggestion that the assets of New Globe had been ‘artificially’ inflated in the 1900 balance sheet. He argued that it was his duty to present the company in the best possible light. If that involved transferring assets from one company to another, that was up to him. Further, his actions had not been responsible for the Globe’s difficulties. They were the consequence of malpractice at Lake View Consols, and he had initiated proceedings against the guilty parties.

Asked why a liability of £150,000 had escaped the books, he answered that the accountant had put the contract notes in a drawer and forgotten about them, something for which he could hardly be held responsible.

When it was revealed that shares in Loddon Valley had been sold to the brother-in-law of the owner of the Financial News on 26 November for £84,562, and repurchased on the following day for £93,537, he denied it was a bribe, adding that the press took little interest in financial matters unless they were directly involved. (As the receiver commented, their interest evidently did not need to be very profound.) [35]

The evidence suggesting fraud was compelling, but the Attorney General resisted calls to prosecute, arguing that the Companies Act (which was tightened in the following year) did not permit it. A petition was raised on the stock exchange and a £25,000 fund raised. In March 1903, Arnold Wright, an author who lost some of his own money in the collapse, claimed that the directors were hiding behind members of the royal family. He declared that ‘a royal duke’ had invested his money and that ‘certain hangers on at court’ were using the name of the king as cover for their nefarious deeds.

George Lambert, the Liberal MP, echoed this strain in Parliament. He suggested the reason why there had been no prosecution was that ‘certain exalted personages’ had been mixed up in the affair. ‘I do not believe a word of that,’ he claimed, but he made his point by drawing the attention to the Globe’s ‘aristocratic directorate, including two lords and a baronet:’

Mr. Whitaker Wright’s evidence was vague, unsatisfactory, and contradictory. If this had been a bank manager, or a bank clerk with a salary of £100 a year, the law would have been upon him at once. There ought to be no difference. The majesty of the law should not be stern in the case of the poor, and doubtful and hesitating in the case of the rich. There have been aristocratic gentlemen mixed up in this affair. I am very sorry for it, but if men with noble names allow themselves to be connected with companies, they must take the consequences of their action. If they use their names as bird lime for the unwary investor, they must bear the responsibility, as they draw their salaries … Fraud and falsification have been openly alleged. Either these directors are much-maligned men or they deserve punishment, and I ask the Attorney General to allow a jury of twelve British men to decide that question.

The Attorney General protested. He did not appreciate insinuations against Lord Dufferin and other members of the board. He conceded there had been transactions at London and Globe that ‘no one for a moment will defend,’ ‘that the persons concerned in them deserve very severe judgment to be passed on them’ and that the transactions ‘should be most thoroughly probed,’ but he declined to authorise a prosecution by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

In this, he was supported by the Solicitor General:

It is said [he argued] that Mr. Whitaker Wright published a false balance sheet. I believe that he did. I think that it is an admitted fact that this was done; but will anyone get up and say that a man can be prosecuted because he publishes a false balance sheet?

The answer was, by inference, in the negative, but many were unimpressed by the government’s defence that the law, as framed, was imperfect. A group of brokers appealed to the High Court Judge, Mr. Justice Buckley, who diverted the blame for the impasse from the Acts of Parliament onto the people who might have used them. He ruled that ‘the apathy of the public in setting the Law in motion has – I will not say encouraged – but has at least failed to repress grievous frauds which have been committed and have too often gone unpunished.’

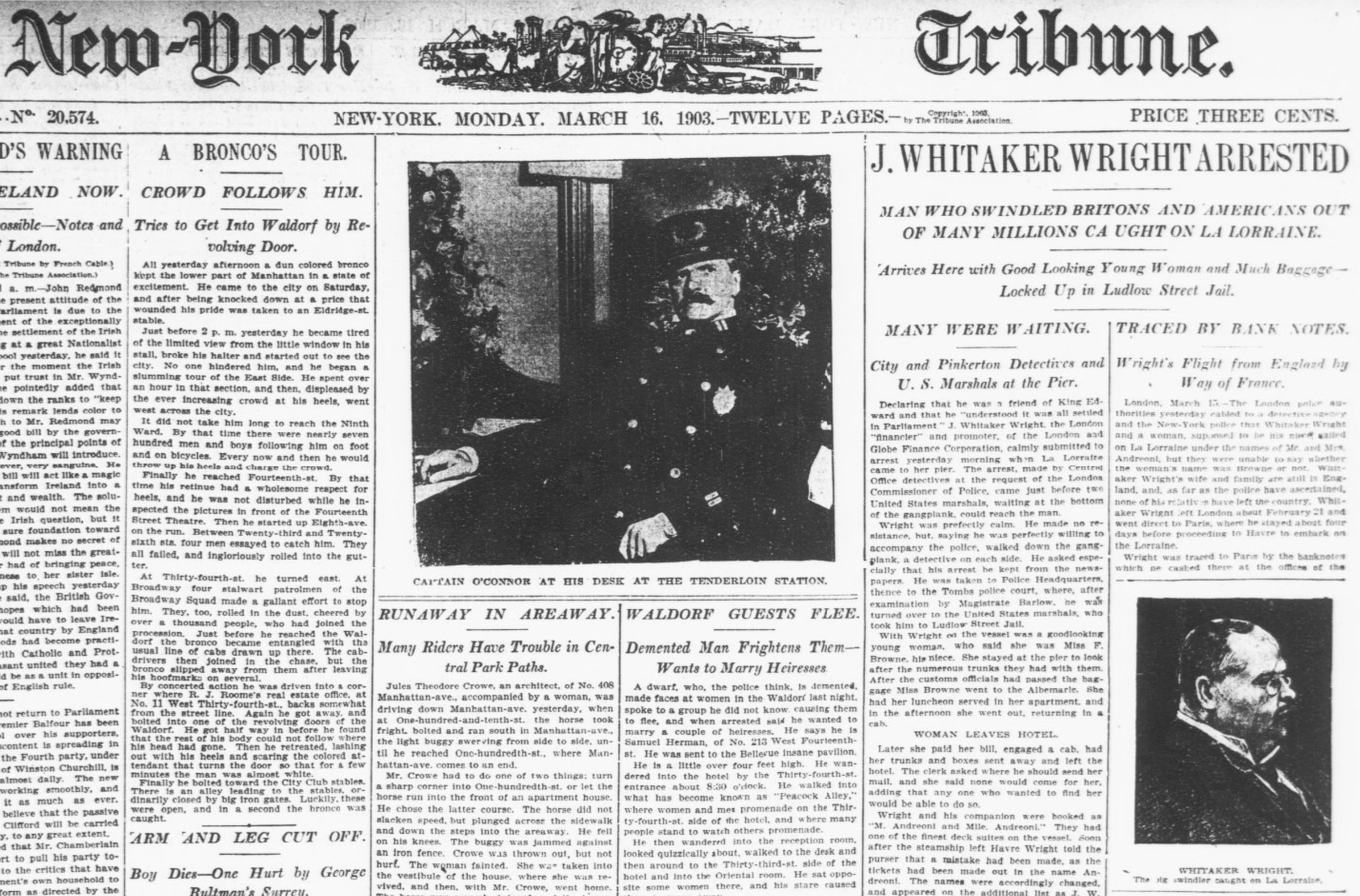

On 10 March 1903, it was decided to charge Whitaker Wright under the Larceny Act of 1861.[36]

By then, Dufferin was dead. ‘When the crash came,’ The New York Tribune reported, ‘Lord Dufferin was severely censured for his connections with the Wright companies, but in a frank speech to the stockholders of the London and Globe he declared his position and won the sympathy of the country. His wealth, at some time large, was believed to have been swallowed up in these companies. His death is believed to have been hastened by these financial troubles.’

The Times was rather less forgiving. ‘What shocked the country,’ it proclaimed, ‘was not the collapse of an ordinary gambling transaction, but the fact that the proceedings of those who entered upon it were sheltered by a great name.’ It had little sympathy for Dufferin’s financial naivety, or his losses:

A pilot who is unskilled and incapable of bringing the ship into port is not to be excused for accepting duties he cannot fulfil because he is ready to go down bravely with the others if he runs the vessel on a rock.

This was hardly kinder than the jibe that went the rounds, ‘Why was Whitaker Wright? Because he took a Dufferin.’[37]

WW ran away to Paris. Then, the American press had a field day when, suddenly, he and his ‘niece’ turned up in New York on board the SS La Lorraine, under the names of Mr. and Mrs. Andreoni. ‘GOT WHITAKER WRIGHT HERE,’ thundered the New York Sun, on 16 March 1903. ‘LONDON’S FUGITIVE PROMOTER NABBED ON LA LORRAINE.’ The New York Tribune reported that WW ‘had tried to conceal his movements by the redirection of his luggage,’ but that he ‘was traced to Paris by the banknotes which he cashed there at the offices of the French Steamship Line.’ London immediately sent an extradition request with a detailed description.

There was no mistaking him. ‘“That’s our man, all right,” said one detective to another, “but he doesn’t look much like ready money.”’ Thus The New York Sun, which reported WW was charged with ‘swindling shareholders of sums aggregating … anywhere between $75,000,000 and $150,000,000.’

WW responded calmly,

I will of course go along with you, but the affair in connection with which I am arrested was a legitimate business transaction and I supposed it had all been settled in Parliament. Let us get away with as little notice as possible and see to it that the newspapers don’t get hold of it.

He claimed that the timing of his departure had been a coincidence. Whilst in Paris, he had received a telegram from the British and America Corporation asking him to look at some mining properties. He hadn’t intended to visit the US until the autumn, when he planned to see the America’s Cup, but then he thought ‘an ocean voyage might act as a bracer.’ Once his troubles were passed, he had ‘a notion’ that he might still see the races. He added, ‘I don’t mind telling you that I think the Cup will be lifted. The latest Shamrock will be a wonder.’ As for travelling under the name of Andreoni, it was the name of the agent who had made the booking. He had had it corrected as soon as he saw the passenger list.

Mrs. Wright, who remained in the UK, told the Tribune that she believed her husband was on the way to Egypt ‘the doctors having declared that a rest was imperative. … His one desire has been to do something for the unfortunate shareholders and the worry told severely on his health.’ When told her husband had been arrested in New York, she said she supposed he had met friends in Paris who had persuaded him to go to New York, perhaps with a view to visiting some mines in British Columbia. She added that, although she was an American citizen, her husband was not. ‘He has always been thoroughly English, much to my disgust. If he had been an American, he would have been properly protected.’

On 18 March, outside the Ludlow Street Jail, WW said it was ‘a cruel shame’ to suggest that the lady who had accompanied him was not his niece. Miss Browne, who was ‘rather tall and slender and … dressed in a dark blue gown and a broad brimmed, low-crowned hat,’ claimed £600 of the £700 taken from WW’s travelling expenses. The British Consul argued they ‘might be the spoils of a crime alleged … involving £5,000,000,’ but the New York Commissioner was sympathetic, arguing that ‘£100 of the £600 she asked for she had really saved from her pocket money.’ Even so, he decided that the numbers on the other notes should be cabled to London for checking.

What seems likely is that, in Paris, WW had visited his mistress, Rosalie. As a result of her extravagant lifestyle, she had amassed gambling debts which she dared not disclose to her husband. WW took advantage of the opportunity to support her, in exchange for sexual favours.

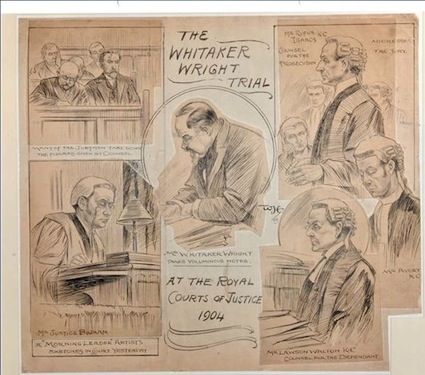

The trial began in January 1904.[38]

The nub of the case lay in the balance sheets of 1899 and 1900. First, the cash balance of £534,455, in 1899. The day before the cut-off date it had been £89,000. Where had the extra come from? Inter alia, £158,424 from the sale of Lake View Consols. to Standard, at £23/share instead of the £8/share market price, and with 3,000 shares that could not be traced in Globe’s accounts borrowed for the time being from Wright himself. This transaction was reversed immediately. £72,000 more came from a paper sale to Standard of shares in International Nickel (which Globe bought back for £80,000 just two months later). Standard had also paid to Globe £359,176, much of which it had borrowed at WW’s order. In spite of all of this, the annual report had said ‘more than the whole amount to the credit of the profit and loss is in cash, a much stronger position than existed last year.’

The 1900 balance sheet date had been put back from 30 September to 5 December. Had the correct date been used, the P&L would have shown a loss of £1.6 million instead of a £463,232 profit. In between times, the company’s accountant had been changed.

Under the prosecutor’s questioning, Whitaker Wright admitted there had been a ‘slip of the tongue’ when he had said the profit had been calculated after a deduction of £500,000 from the market value of shares in Lake View Consols. There had been another ‘slip of the tongue’ when he had said that the company’s policy was to value its £2,332,000 in investments at the lower of cost or market value. (The board’s earlier remark about a conservative provision of over £1 million, for possible depreciation, was dismissed as an ‘extempore utterance.’) In fact, not only had the position in Lake View not been marked down by even a penny, but a holding of 410,235 shares in Standard had been priced at 20/3d per share. instead of 9/9d.

In addition, an item of £113,671, 9s.10d. in cash (as the prosecuting barrister called the ‘10d’ an ‘artistic touch’) had been manufactured from short term loans from the bankers. As to the omission of £1,603,000 of liabilities to stockbrokers which had been transferred to Standard, there was no denial. Rather, it was claimed the intention had not been to deceive; it was to save the shareholders from the ‘bears’ who were out to wreck the company.

WW stood no chance. The jury took just an hour to reach its verdict. Sentenced to seven years penal servitude, he was escorted to a side room of the court, where he lit a cigar and, taking a glass of whisky, swallowed a cyanide tablet. A fully loaded revolver was found in his coat pocket.[39]

But yesterday the word of Caesar might

Have stood against the world; now he lies there

And none so poor to do him reverence.

In January 1904, the literary critic John Churton Collins reflected popular opinion when he inspected WWs body at the mortuary at the Horseferry Road. He wrote,

The general impression was a large broad face most strikingly coarse and plebeian … The mouth, which was partially open, as well as the lips, was large and most grossly sensual; the lips looked swollen and were a ruby crimson in remarkable contrast to the yellow face: the chin was mean, with a short, scrubby, grey grizzled tuft for a beard. The skull was shaved, no hair visible and white. The forehead most mean remarkably receding, except along the frontal bone, where it was strikingly developed, tense and corrugated, as if anxious thought had ploughed so deep that the repose of death could not smooth it out … In the frontal development, and in that alone, was there anything to redeem the features from mere animalism, from those of the average low type of petty tradesman or huckster.

And yet WW had his supporters. He had given generously to the poor of his neighbourhood in Surrey and had built community halls in both Witley and Milford. (His offer to replace Witley’s eleventh century church with something more modern was politely declined.). At his funeral, the village windows were shuttered as a mark of respect and the population appeared in large numbers to lay posies of wildflowers on his grave.

WW’s original epitaph, since removed, said simply, ‘He loved the poor.’ Today, it reads, ‘Until the day breaks and the shadows flee away.’ Perhaps the change was made when Anna was buried beside her husband, in 1931.[40]

Dufferin never recovered from his reverse. He felt it extra painfully because it came at a time when, with the rise in the value of his shares in Whitaker Wright companies, he was enjoying the fruits of real money for the first time. At the end of the 1890s, he bought two farms adjoining Clandeboye and a luxury yacht, which he called Brunhilde. On one occasion, he wrote to Ronald Munro-Ferguson, later Governor of Australia, who had married his daughter Helen, ‘we must build adjoining palaces in Park Lane as soon as our fortunes are made.’

Another ‘terrible blow’ was the death of his son, Archie, in the Boer War, in January 1900, even if comfort could be taken from the knowledge that ‘the poor boy died in the discharge of his duty to his Queen and country … instead of perishing by fever in one of our many unsuccessful engagements.’ In December, Dufferin heard that a second son, Freddie, had been badly wounded at Gelegfontein. He and his wife booked a passage to South Africa just two days before the bankruptcy of the Globe was declared. To his credit, Dufferin had it cancelled so that he could face the shareholders.

In Dufferin’s final years, Sir Edward Grey wrote to Helen Munro-Ferguson, to say, ‘The knowledge of the spirit in which Lord D. faced all the troubles of the last few years has stirred me very much … Adversity set [his qualities] in relief, and made one see how strong they were, and how fine-tempered the metal.’ Dufferin had been right to describe the failure of the Globe as ‘an indescribable calamity which will cast a cloud over the remainder of my life.’ Instead of retirement ease at Clandeboye, he was obliged to hock his family’s assets. He even considered selling the house. Richard Brindsley Sheridan’s inglorious end cannot have been far from his mind. He died on 12 February 1902.[41]

Happily, Clandeboye survived. Lea Park did not fare as well.

After Whitaker Wright’s suicide, his wife Anna lived on at the Parsonage, one of the farms on the estate. It was run by her son, Whitaker Wright II. Lea Park mansion was put up for sale in July 1904. It found no buyer, although forty-four of fifty lots of the estate were sold, in October 1905, for £50,120. The Manor of Witley was bought by a Mr. Prichard, in 1906, for £1,000. Much of the land on Hindhead Common, Witley Common and Thursley Common was sold to the National Trust, of which (ironically) Lord Dufferin had once been president.

Lea Park was eventually bought by Lord Pirrie, the chairman of Harland and Wolff, in 1909. In 1912, Whitaker Wright’s son married, and Pirrie bought the Parsonage farm. He converted much of the estate into a deer park, fenced with iron fences and gates, many of which remain in situ a hundred years later.[42]

In the 1920s, the estate was renamed ‘Witley Park’ by Sir John Leigh, a cotton magnate. In May 1952, it was sold to Mr. Ronald Huggett. A syndicated report of his purchase was printed in The Truth, a Melbourne tabloid, in June of that year. Under the sub-title ‘The Meat Pie King Moves into Aladdin’s Palace,’ it claimed:

Portly, bewhiskered Ronald J, Huggett, 39-years-old huntsman, amateur racing driver and king of Britain’s canned meat industry, caused more than a momentary stir recently when he handed over a fortune in exchange for an Aladdin’s palace in the heart of the Surrey countryside. Shortly after the purchase he clambered from a £3,000 carnation-coloured sports car and told a newspaper reporter,

“The purchase has left me a poor man, but I believe that to get something out of life you must put something into it … I want to transform this playground of bygone days into a food producing unit – create a modern business to meet present-day requirements, successful enough to carry its own expenses.” …

And the house itself?

“First, I shall get rid of the monstrosities … even if it means pulling down a third of the whole structure.”

Down will come the circular glass roof of the 92ft x 42ft winter garden, where Whitaker Wright once contemplated his home-grown palm trees.

“It may be suitable for Kew Gardens,” said Mr. Huggett, “but not for a private house.”

He is considering several offers from seaside corporations anxious to find a venue for their Sunday night concerts.

On the east wing, a half-timbered Elizabethan-style structure will be torn down and modernised. Out will go the massive quadrigas in white Roman marble, and Moorish arches built for posterity by an army of 2,900 workmen, many of them from Italy.

Will he preserve the glass-walled underwater billiards room that Whitaker Wright built on the bed of the lake? It was there that Wright, who finally sought peace with a phial of poison after a penal sentence in 1904, used to pause between shots to observe his unrivalled stock of fish …

“To demolish the passage and the room would be a major operation,” said Mr. Huggett, “so they must stay”.

Behind, too, stays an L-shaped bridal suite, each arm 74 feet long, a 54ft. square oak-floored dining room, smaller dining rooms with panels fashioned from the finest Havannah cedar, a 15-car garage, and a long bank of cookers to feed 400 guests at one sitting.

“We shall need only 10 to 12 bedrooms,” said Mr. Huggett, thinking of the housekeeping problem for his 24-years-old wife Mary. So at least 25 bedrooms, once tended by some of the 77 servants employed at Witley Park, will vanish …