Burma and China: Before the First Anglo-Burman War

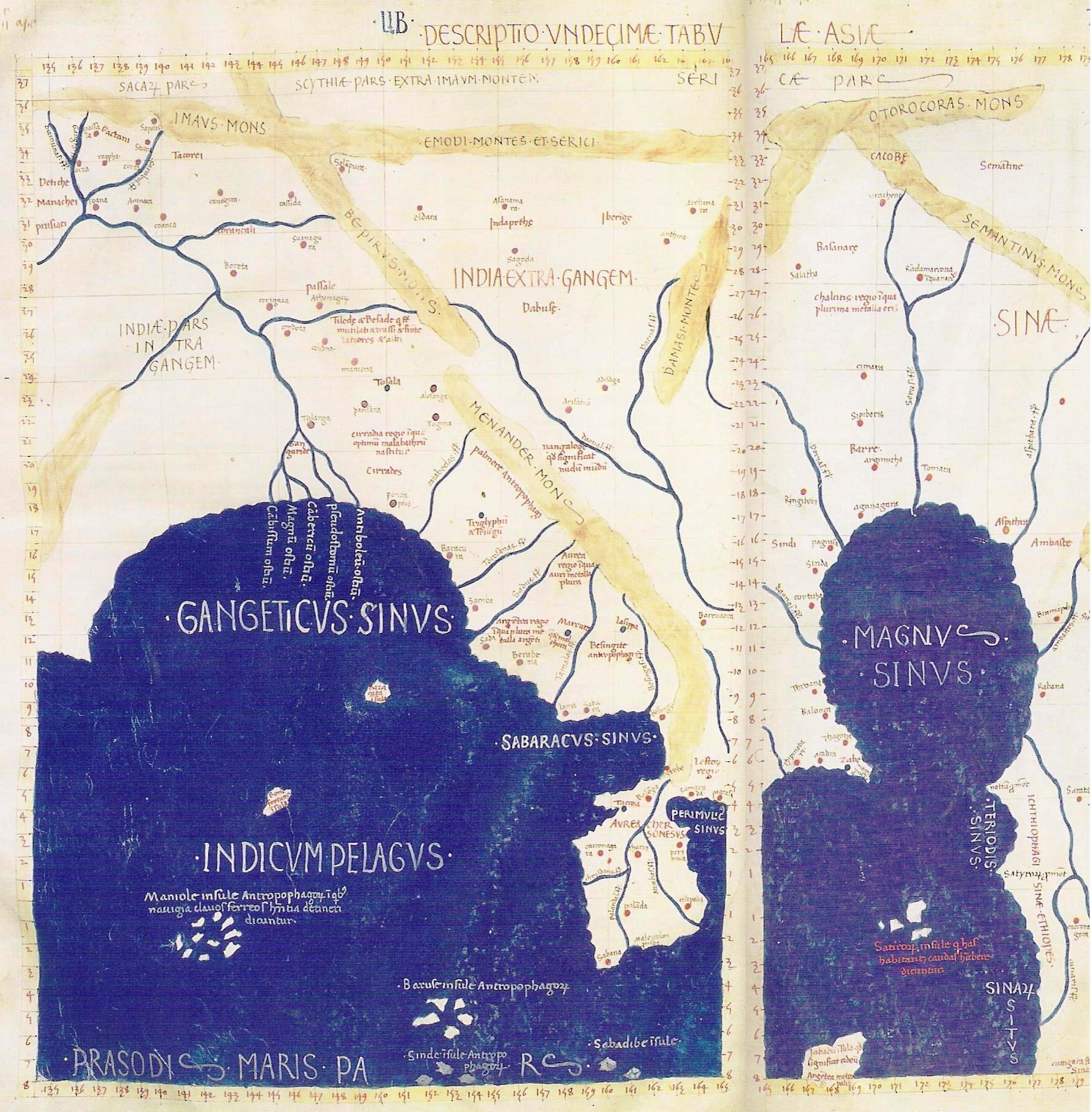

Kashgar, Yarkand and Khotan, the first sources of jade known to the Chinese, were conquered by the Emperor Qianlong between 1755 and 1759, and from them he is said to have extracted more than four tonnes of raw jade annually. Officials such as Ch’i-shih-i, who oversaw the process, sent word of the White and Green Jade Rivers, where native women waded, thirty abreast, feeling for jade with their toes, assisted in their search by the female yin that attracted the male yang that came from the stones. However, the quality of the jade there did not match that of the stone that the Han poet Ban Gu called fei-ts’ui. The source for this lay three thousand miles to the south-west, in a land called Mien-Tien, where a Yunnan trader had once picked up a piece of green stone to balance the load on his mule. When he discovered its value, he and others tried to retrace its source, but without success. Repeated efforts were made in subsequent years until, in the fourteenth century, all the members of a large expedition sent to discover the mines perished at the hands of the hostile Kachin tribes inhabiting the area, and as a result of the pestilential climate. [3]

Yet the Chinese did not forget the stone on which they had set their heart, and of which the Kachins had deprived them. Once they appreciated the value the emperor put on the rocks that they used to support their cooking pots, the Kachin chiefs must have allowed just enough to trickle across the border to keep his interest alive. Then, according to the Burmese account, a chance to pick a quarrel arose, in 1765, when a Chinese merchant was killed in a bar-room brawl in the frontier state of Kengtung. Whether this incident, of itself, was sufficient to precipitate the subsequent Chinese invasions is to be doubted. But the frontier had been troubled for a few years by the activities of the Gwe, a restive tribe who upset both the Burmans, by harbouring the heir of one of their deposed kings, and the Chinese, by launching a series of raids into Kenhung, which the Chinese regarded as an “inner dependency”. The emperor, determined not “to allow another man’s spittle to dry on my face”, now ordered an expedition “to make Mien-Tien as unhappy and uncertain as possible.” [4]

The foray proved to be a disaster. In the 1280s China had easily defeated the kingdom of Pagan, but now it faced the Alaungpaya dynasty, soon (in 1767) to be the conquerors of Ayudhya, the capital of Siam. In a sign that they under-estimated their opponents, the Chinese selected as their first commander, not a military professional, but Liu Zhao, the civilian governor of Yunnan. After his defeat at Puer, in 1766, he pretended that his reverse had been a victory and, when he could no longer sustain that lie, he slit his own throat rather than face recall to Peking. In 1766-1767, his successor, Yang Yingju, sustained a major defeat at Bhamo. He reported that disease was so rampant in his army that Burma was “not worth the trial”, but the emperor was unpersuaded. Unlike Liu, Yang Yingju accepted his punishment. He was summoned home, and there he was “graciously permitted to commit suicide”.

Thereafter, the Chinese became more serious. In 1767, Mingrui, a veteran of the campaign in Xinjiang, fought his way past Lashio and, with an army of fifty thousand, forced his way to Singu, within three days march of Ava. But he overextended himself. In early 1768, after he had been cut off in the rear, and his provisions had been exhausted and his bannermen were succumbing to malaria, he ordered a retreat. Few made it home and, at the frontier town of Wanding, Mingrui ended his life by hanging himself in a tree.

Finally, in December 1769, after another unsuccessful offensive by General Fuheng, which included a plan for a naval campaign on the Irrawaddy that, fatally, was launched at the height of the monsoon, the Qing literally burned their boats and retreated up the Shweli valley, never to return. [5]

Following the truce, Burmese embassies were sent to China in 1782, 1787, 1792 and 1793. The last coincided with the mission of Lord Macartney, who was sent by George III to negotiate improved access for Britain to China’s ports. This much is clear from the account of Sir George Staunton, who wrote that his audience ended when “embassadors from Pegu … were introduced to the Emperor, … repeated nine times the most devout prostrations, and were quickly dismissed.” [6]

The Macartney mission was a failure and so, as a face-saving measure, the British took the opportunity to contrast their treatment with that of the Burmese. Macartney and Staunton, they said, received from the emperor the gift of a “gem or precious stone, as it was called by the Chinese, and accounted by them of high value. It was upwards of a foot in length, and curiously carved into a form intended to resemble a sceptre … considered as emblematic of prosperity and peace.” By contrast, they asserted that the delegation from Pegu came “to acknowledge a sort of vassalage to China, by sending tribute, and paying homage, to the Emperor, in order to avoid a more direct interference.”

The condescension continues:

Those delegates were placed under the conduct of some inferior mandarins …. [who] gave way to the contempt which they felt for those foreigners … [They] felt little scruple in taking advantage of so favourable an opportunity to derive emolument from defrauding the persons under their care. Luckily in such circumstances those men had been habituated to the hardships of a military life; and their minds were not so refined as to feel humiliation very poignantly; and their chief mortification, perhaps, arose from the superior treatment of the English Embassy.

Yet it has recently been suggested that the Burmese delegations of the 1790s had a special significance. In 1788, it is said, King Bodawpaya came to an arrangement with the tribes controlling the jade mines, and formally promised quantities of their output to the Chinese emperor as tribute, in exchange for princely status, and peace. Whether this was quite the case is not, in fact, clear, although there was certainly significant trade in jade between Burma and China by early in the next century. Certainly, it would not have been characteristic for the Burmese to have considered themselves “tributary” to China in the way the British perceived them to be. By 1793, however, it is possible that they had made some concessions on status, and relations between the two states certainly improved, after diplomacy got under way. [7]

Staunton says the gifts between the Macartney’s delegation and the emperor “were probably, on both sides, less valuable in the estimation of the receivers than in that of the donors”, so perhaps the British would not have been greatly interested in these developments, even if they were as suggested. Whether or not they missed the message of the Burmese envoys on this occasion, however, the trade in jade was destined to remain a secret for just a few more years. Shortly afterwards there was a collision between British and Burmese empires which was guaranteed to bring it into the open.

From the 1780s, as the Siamese consolidated the country around their new capital of Bangkok, the Burmese switched the focus of their international expansion to the west, in the direction of Arakan, Manipur and Assam. Calcutta became alarmed and eventually, in March 1824, Lord Amherst declared war. The First Anglo-Burmese conflict was the most expensive in British Indian history. It cost the East India Company its last privileges (including its monopoly on the China trade) but, at its end in 1826, Britain was granted permission to set up a permanent residency at Ava. As they explored further north from there, the British soon began to get a sniff of some “much talked of serpentine mines.”

The Explorations of Captain SF Hannay (1835-1836)

“I have observed daily three or four boats going up and down the river”, wrote Lt. Mcleod to Major Henry Burney, the British Resident at Ava, in December 1833:

They are all bound for the Oroo River … The noble serpentine is found on the bed of this stream at Mogaung, within one mile of which there are some hills from which it is also dug … Chinese merchants appear to monopolise this article … They come to the place above-mentioned annually and pay large sums of money for it … His Late Majesty employed 3,000 men to procure some and they succeeded in transporting three large boulders of it to the capital, from which cups etc. were made. [8]

These remarks registered, and henceforth Major Burney resolved to exploit any opportunity that came his way to investigate the matter of the “serpentine” trade with China. His first chance came with the need to regularise the border between the Burmese frontier provinces and India’s Assam. In November 1834, Captain HL Jenkins, the Indian governor-general’s agent on the northeast frontier, reported there was a significant amount of trade in these districts, with “more than one well-used trade route through Hookong (Hukawng), and through the Sepahee Singpho (Kachin) country to Tali and other places in China”. He was willing to permit Burmese traders to visit Assam, and to let them enjoy British protection and exemption from imposts, provided these were reciprocated. However, he knew little about conditions in the Kachin areas on the Burmese side and was unsure how much authority the Court of Ava exercised over them.

The Government of India referred the matter to Henry Burney, for his views. His response was not encouraging:

A very extraordinary degree of ignorance regarding the whole of the Shan States prevails among the Burmese Ministers, not one of whom really knows anything of the country lying between Mogaung and Assam …

The Court of Ava are extremely jealous of foreigners having any communication with the Shan states over most of which Burmese supremacy is not very secure …

The Burmese Government exercise very little authority over the Simphos or Theinbuns and other wild tribes who occupy the country between Assam, Yunnan and Ava. Even the Chinese caravans which are numerous have sometimes been attacked by these mountaineers, and the Burmese say, that a Theinbun always prefers killing a man to cutting down a tree as the possession of a common waist cloth or tinder box only from a man they may kill is wealth to a Theinbun.

I see no chance also of the Government of Ava giving up the 10 per cent duty levied on imports into their country, as the amount of this duty is fixed by their oldest code of laws, and is considered as ancient as the Empire itself. [9]

Conveniently for the British, however, as Burney’s advice was being considered, the Daffa Gaum (Dupha Gam), a chief from Hukawng, crossed the frontier into Assam and, with his followers, attacked another Singpho chief, the Beesa Gaum, who was living in British territory. He destroyed the Beesa Gaum’s village and massacred everyone he could lay his hands on before occupying his lands and claiming them as his own.

Burney was instructed to remonstrate with the Ava government but, when he did so, he found that – to his no great surprise – they knew next to nothing either of the Daffa Gaum or of the frontier in question. Then he discovered that a new governor (Myo Wun) of Mogaung had recently been appointed and was about to leave Ava for his northern headquarters. Seizing the occasion, with some difficulty he persuaded the authorities to permit Captain Hannay, the officer commanding his residency escort, to accompany the Myo Wun on his journey. [10]

In November 1835, the party left in a fleet of thirty-four boats of various sizes “for a part of the country which had been uniformly closed against strangers with the most jealous vigilance”. According to the official report,

No foreigners except the Chinese are allowed to navigate the Irrawaddy above the Choki of Tsampaynago, situated about seventy miles from Ava, and no native of the country is permitted to proceed above that post, excepting under special licence from the Government. The trade to the north of Ava is entirely in the hands of the Chinese, and the individuals of that nation residing at Ava have always been vigilant in trying to prevent any interference with their monopoly.

The Burmese troops accompanying the mission proved a rough lot, “whose discipline … was very soon found to be on a par with their honesty”. Hannay writes,

Their muskets (if they deserve the name) are ranged here and there throughout the boat, and are never cleared either from rust or dust, and wet or dry they are left without any covering. Each man carries a canvas bag, which is a receptacle for all sorts of things, including a few bamboo cartridges. He wears a black Shan jacket and a head-dress or goung-boung of red cotton handkerchief, and thus equipped he is a complete Burman militia man. They appear on further acquaintance to be better humoured than I at first thought them, but they are sad plunderers, and I pity the owners of the fields of pumpkins or beans they come across. I have remarked that whatever a Burman boatman eats in addition to his rice, is generally stolen.

Despite this, the journey passed without mishap. Demonstrating “a gratifying proof of the friendly feeling generally of the Burmese authorities”, the people whom Hannay encountered proved extremely hospitable, erecting houses for his accommodation wherever he stopped, providing presents of fruit, rice and vegetables, and furnishing bands of singers and dancers to relieve the tedium of his evenings.

At Katha, about two hundred miles above Ava, where the Irrawaddy was confined between banks no more than 450 yards apart, the flow of the river was estimated at 52,272 cubic feet per second (sic). Yet, navigation proved relatively straightforward. Even at the third defile above Bhamo, where the river’s breadth was reduced to as little as eighty yards, with a depth of thirty feet, the river “coursed gently along with an almost imperceptible motion”. Yet, in the rains, when the waters rose by as much as fifty feet and the roar would be such as to make conversation impossible, Hannay well appreciated that the current must have been “terrific”.

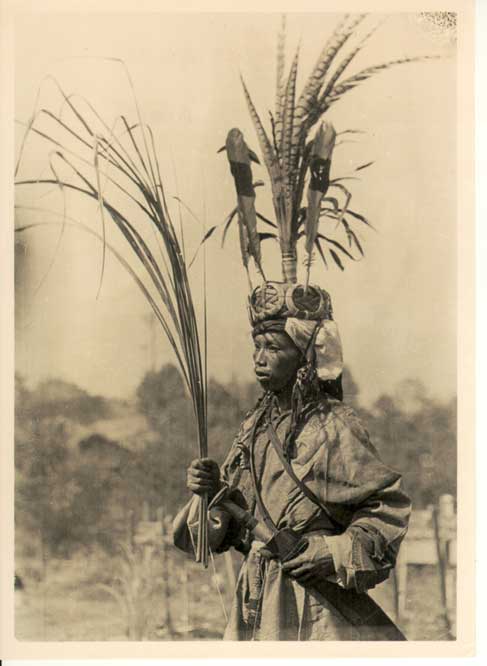

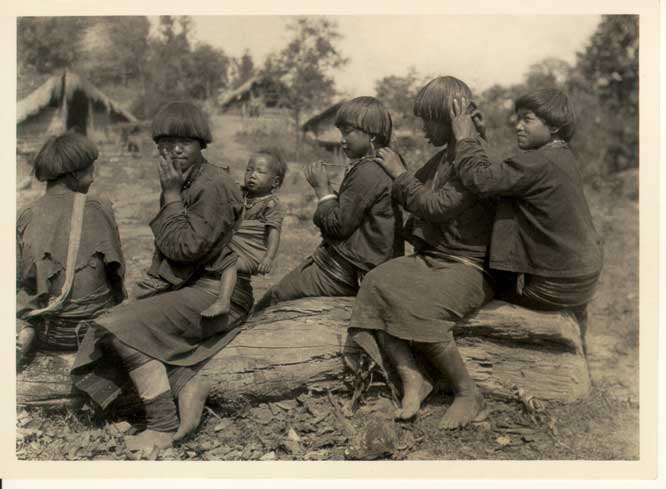

Above Bhamo, the going became a little tougher in another respect. At Hakan, the escort was reinforced by 150 Shan soldiers from the neighbourhood. According to Hannay, these “formed a striking contrast in dress and appearance to the miserable escort which had accompanied the party from Ava.” They were needed to guard against surprises by the Kachins, whom Hannay had first encountered at Koungton on 20 December, and whom he describes as “perfect savages in their appearance”:

Their cast of countenance forms a singular exception to the general rule, for it is not at all Tartar in its shape, but they have on the contrary long faces and straight noses, with a very disagreeable expression about the eyes, which was rendered still more so by their lanky black hair being brought over the forehead, so as to entirely cover it and then cut straight across on a line with the eyebrows. These people, though surrounded by Shans, Burmese, and Chinese, are so totally different from either, that it is difficult to imagine from where they have had their origin.

Ten miles above Tshenbo (Sinbo), the party left the Irrawaddy for the Mogaung River, switching from their larger vessels to boats of a type better suited to the small, tortuous stream and its succession of rapids, some of which were judged to be “exceedingly dangerous.”

The way in which the Phwons and Shans overcome these difficulties formed a striking contrast to the conduct of the Burmah and Kathay boatmen. The former, working together with life and spirit, still paid the strictest attention to the orders given by the head boatman; while the latter, who think … that nothing can be done without noise, obey no one, as they all talk at once and used the most abusive language to each other.

Finally, on 5 January, at the cost of one boat lost and one man drowned, the fleet reached the town of Mogaung:

Arrangements had been made for our reception, and on first landing we entered a temporary house, where some religious ceremony was performed, part of which was the Myo Wun supplicating the spirits of three brothers who are buried here, and who founded the Shan provinces of Khanti, Assam, and Mogaung, to preserve him from all evil. After which ceremony he dressed himself in his robe of state, and he and I proceeded hand in hand through a street of Burman soldiers, who were posted from the landing place to the Myo Wun’s house, a distance of nearly a mile. We were preceded by the Myo Wun’s people carrying spears, gilt chattas, &c, and at intervals during our walk a man in a very tolerable voice chanted our praises and the cause of our coming to Mogaung. Several women also joined the procession, carrying offerings of flowers and giving us their good wishes.

Almost immediately, the Myo Wun set about implementing “a system of unsparing taxation” to pay for his appointment:

A rapid succession of governors within a very few years, all influenced by the same principle, had already reduced the inhabitants of Mogaung to a state closely bordering on extreme poverty, and the distress occasioned by the exactions now practiced was bitterly complained of by the wretched victims of such heartless extortion. The Shan inhabitants of the town were employed by the Burmese officers to enforce this excessive payment of tribute from the Singfos and Kakhyens (Kachins) of the surrounding hills, which had led to much ill will on the part of the latter, by whom they are stigmatized “as the dogs of the Burmans.”

The town did not impress. Hannay wrote, “Were it not for the Chinese, whose quarter of the town looks business-like and comfortable, I should say that Mogaung is decidedly the poorest looking town I have seen since leaving Ava.” Including the profits derived from the sale of serpentine, the revenues of the neighbourhood were estimated by him to be no more than thirty thousand rupees per annum. He added that the authorities could only enforce the payment of tribute by the presence of an armed force – and then not always successfully, for in their last attempt on the Kachins, out of a force of one thousand men, nine hundred had been destroyed. Since then, he reports, for a decade the Kachins “had been held in salutary dread by the Burmah governors on the frontier.”

For a while immediately after his arrival, Hannay was occupied in answering questions put to him by a crowd of visitors. First, they examined his sextant “under the firm conviction that, by looking through it, he was enabled to perceive what was going on in distant countries.” Then he was obliged to dismantle his compass, in order to satisfy them that its needle was not indeed floating on water. If this was an inconvenience, however, his demonstrations served as a useful confidence building measure for, after a while, some of the townsfolk reciprocated by bringing out for his inspection some specimens of a green stone, called by the Burmese “kyouk-tsein” and by the Chinese “yueesh”:

The Chinese [Hannay writes] choose pieces which, although shewing a rough and dingy-coloured exterior, have considerable interior lustre, and very often contain spots and veins of a beautiful bright apple-green. These are carefully cut out, and made into ring stones, and other ornaments, which are worn as charms. The large masses are manufactured by them into bracelets, rings and drinking cups, the latter being much in use amongst them, from the idea that the stone possesses medicinal virtues. All the yueesh taken away by the Chinese is brought from a spot five marches to the north-west of Mogaung, but it is found in several other parts of the country, although of an inferior quality.

From Mogaung, Hannay hoped that, to fulfil his mission, he might be allowed to cross the Patkoi mountains into Assam and, to this end, he waited for some days in order to assemble a party of Kachin porters to help with his supplies. Then the Myo Wun refused him permission to go. Without the support of a full military contingent, he explained, his authority as a Burman would be “held in the most sovereign contempt”, and Hannay would not be able to rely on his escort’s protection.

Indeed, it was only after Hannay made a powerful protest that the Myo Wun was induced even to let him take a small party to investigate the nearby Hukawng valley, which was known for its amber. At length, they set out on 22 January, after performing the ceremony of sacrificing a buffalo to the Nhatgyee, or the “spirits of the three brother Tsanhuas of Mogaung”, the necessary preliminary to any expedition that set forth from the town. Hannay continues,

The men, to the number of 800, march in single file, and each man occupies a space of six feet, being obliged to carry a bangy containing his provisions, cooking pots, &c, besides his musket, which is tied to the bangy stick. This is the most common mode of marching, but some of them carry their provisions in baskets, which they strap across their foreheads and shoulders, leaving their hands free to carry their muskets; but as to using them it is out of the question, and I should say the whole part are quite at the mercy of any tribe who choose to make a sudden attack upon them.

The route passed along a series of defiles bounded by steep hills, which, to great effect, funnelled the waters of the numerous streams that made their way to Mogaung. Of human habitation, there was little indication, except for some cleared spots on the hills, a few fishing stakes in the streams themselves and, in one location, a deserted village “completely strewed with graves”. Hannay decided these betokened of some sort of endemic disease, in the face of which the remainder of the population had fled.

At Tsadozant, the party crossed the Mogaung stream for the last time, Hannay noting, as they did so, that its bed was “composed of rolled pieces of sienite and serpentine with scales of mica in it.” Four miles on, he crossed a transverse ridge, the Tsambou Toung, and so he entered the Hukawng valley. Of the amber he had hoped to see there was little trace, and Hannay was greatly disappointed. The only explanation, he thought, was that advance warning of his escort had caused the people to secret away what they had recovered for, although he inspected ten pits, he didn’t see a single piece of amber worth having. On the other hand, from the Shan village of Meingkhwon (Maing Khwan) he obtained his first view of the hill which served the sources of the Uru river, celebrated for its mines of serpentine:

A line drawn from Mogaung in a direction of N. 55 W. and another from Meingkhwon N. 25 W. will give the position of the serpentine mine district. The Chinese frequently proceed to the mines by water for two days journey up the Mogaung river, to a village called Kammein, at which place a small stream, called Engdan-khyoung, falls into the Mogaung river. From thence a road leads along the Engdan-khyoung to a lake several miles in circumference, called Engdan gyi (Indawgyi), and to the north of this lake, eight or nine miles distant, are the serpentine mines, the tract of country in which the serpentine is found extending 18 or 20 miles. [11]

Whilst he was in the vicinity, Hannay made numerous enquiries about the duties levied on the Chinese traders in jade. And quickly he decided that, for all of its reputation, very little monetary benefit was percolating from the business into the royal treasury. It was apparent that there was no regularity in the payment of taxes, and that a great deal depended “on the value of the presents paid to the head-man.” And, in respect of jade, that was about as far as he got. For the governor, having “raised by threats and the practice of every art of extortion as large a sum as it was possible to collect from the inhabitants of the valley and the surrounding hills”, had decided he was no longer welcome.

In this he was not mistaken, although he was not alone. Speaking to Hannay about the various authorities with whom he had to deal, one of the Kachin chiefs ranked them as follows:

The British are honourable and so are the Chinese. Among the Burmans you might possibly find one in a hundred who, if well paid, would do justice to those under him. The Shans of Mogaung are the dogs of the Burmans, and the Assamese are worse than either, being the most dangerous back-biting race in existence.

Hannay immediately despatched Sindhur Singh, one of his sepoys, to try to find a practicable trade route from Mogaung to Sadiya in north-eastern Assam, but he and the remainder of his party were put under orders immediately to return downstream to Ava. They reached it eighteen days later.

To his credit, sepoy Singh made it through and, in the process, he discovered a road which he thought might be made practicable for wheeled carriages. Burney was delighted. To his government he wrote:

I would recommend that some pretext should be found for sending an officer from Assam to me here via Maingkom (Maing Khwan) and Mogaung. After two or three such occasions not only a trade between Assam and this country would be placed on a more secure footing, but I think the court of Ava would remove the prohibition which it now interposes to our traders proceeding above Ava towards Bamau (Bhamo) and Mogaung and disturbing the monopoly which the Chinese have long enjoyed of the whole trade in that quarter.

Then the true reason for Hannay’s enforced departure emerged. In May 1836, Burney wrote to his superiors:

I beg further to report that having received intelligence that a letter had lately arrived here from the Chinese Provincial Governor of Yunan remonstrating with the court of Ava for having allowed an English officer to proceed to the northward and ascertain the route to China, I questioned the Burmese Ministers who admitted the fact of a letter having been received from China but denied its Contents were anything other than a Complimentary communication relative to a new title conferred by the Emperor of China on his mother. I am inclined however to credit the intelligence I have heard because I am aware that shortly after Captain Hannay left Ava, in December last a Deputation of Chinese Merchants residing here waited on the Prince Minthagyee (Minthagyi)to demonstrate against the mission. Their remonstrance proceeded from a natural apprehension that the monopoly which they have long held of the whole trade to the north of Ava and of the produce of the amber and serpentine mines, might be disturbed by an English officer exploring the country in that direction and communicating freely with its inhabitants.

In the following September, Burney obtained, through a secret agent, a copy of the letter that had been sent to Ava. Since it corroborated his earlier opinion, he provided a translation, with an explanatory parenthesis:

It is not proper to allow the English after they have made War, and Peace has been settled, to remain in the City. They are accustomed to act like “Pipal” Tree (wherever this plant takes root and particularly in old temples and buildings it spreads and takes such firm hold that it is scarcely possible to be removed or eradicated …) Let not Younger Brother therefore allow the English to remain in his country and if anything happens, Elder Brother will attack, take and give. [12]

The Expeditions of Dr William Griffith and George Bayfield (1836-1837)

Needless to say, the emperor’s sentiments agreed closely with those of the government at Ava. But Calcutta was not put to be off. Hannay and Sepoy Singh were summoned immediately to Fort William “in order that Government may avail itself to the utmost possible extent of the information which they are in possession of”. And, if Hannay thought his previous exploits would earn him a period of extended leave, he was soon disappointed. In early 1837, he was sent back across the frontier in the company of Dr William Griffith, a botanist who had been studying tea cultivation in Assam, and Major White, the political agent of Upper Assam.

Meanwhile, at Ava, Burney had been busy trying to persuade ministers to explore the potential for trade between northern Burma and Assam. In this he was unsuccessful, as they showed themselves to be quite uninterested in commerce, even exclaiming at one point that it was a matter for merchants only and bore “no relation whatever to the affairs of the country”.

After this rebuff, Burney tried a different tack and eventually, by one means or another, he managed to convince them that, if his deputy, George Bayfield, were permitted to rendezvous with the deputation from Calcutta, the feud between the Daffa and Beesa Gaums might be dealt with. In addition, he explained that, if Bayfield travelled with the Myo Wun and the Daffa Gaum on their next tour, they could determine with Major White precisely where the frontier between British and Burmese territory lay. Once that had been done, it was Burney’s hope that Hannay and Bayfield would be able to return together to Ava and so complete “a proper survey of the whole route”. [13]

Griffith and Hannay left Sadiya on 7 February 1837 and crossed the Ramyoom stream at the boundary with Burma on 3 March. The journey across the Patkoi hills will certainly have been fatiguing, as it involved several climbs of a thousand feet and more and Griffith, who was an expert in such matters, judged the jungle at the border “the wettest and rankest” he had ever seen. For all of this, however, Griffith’s account comes across as rather matter of fact, comprising, in large measure, notes about the vegetation (as one would expect), coupled with references to the quality of the fishing. Bayfield’s journey was rather longer and altogether more arduous.

He left Ava on 13 December 1836 accompanied by a party of thirty-two people, “including boatmen, servants and a liberated Assamese slave, who had found his way down to Ava in the train of a wandering fakeer”. It was arranged that he would meet the Myo Wun of Mogaung a few days later at Tsingu, where he was due to celebrate the investiture of his son into holy orders. This gave Bayfield time enough to visit the site of King Bodawpaya’s Mingun pagoda:

The ascent to it was by zigzag flights of steps, or rather ladders, of which formerly there was one at each face, but three have fallen down from old age; the fourth stands, but it is in no very inviting condition, and about half way up has such an ominous slant as to make one wish one’s self safe either up or down. Arrived at the summit, the beauty and comprehensiveness of the view fully repays one for the trouble, at least if not for the seeming danger of the expedition, and would be quite delightful if it were not for the uncertainty of the passage down again. [14]

On 17 December, Bayfield was received at Tsingu by the Myo Wun. Two days later they were joined by the Daffa Gaum, who arrived in a boat decorated with a covering of scarlet cloth and two golden umbrellas (“chattahs”). Bayfield was not deceived. There was, he says, “a sad want of the substantials about his general equipment.” The Myo Wun clearly despised him, and, whilst Bayfield tried to ensure he was accorded a measure of respect, he also made it clear there was to be no room for negotiation with Major White about the frontier, and that a repeat of his earlier conduct would be severely dealt with. Hereinafter, the Daffa Gaum portrays a rather sad picture. [15]

The journey from Tsingu to Bhamo was relatively uneventful although, on occasion, Bayfield was left wondering at the Myo Wun’s conversation, and some of the hospitality he was afforded he found a challenge. Thus, on the evening of 27 December, he writes,

I visited the Myo Wun, whose shed was within 50 yards of my own, the intervening space being occupied by a leaf canopy, under which a play was performing, for our amusement. After a little time, the Myo Wun, who piques himself upon his knowledge in geography, enquired if I had ever visited China, or seen the inhabitants of a large island three days’ sail across a narrow channel beyond China, who, he said, were a very powerful race of men, five cubits high, with ears eight inches long, and members of a still larger proportion. I was obliged to confess my ignorance.

At Kyouk-gyih, Bayfield unavailingly tried to excuse himself from an offer of dinner shared with the kindly Myo Wun of Monhyen:

Seeing that I could not now help myself, I had nothing more to do than express how delightful such an arrangement would be to me, although at the thought of Burmese cookery certain stomachic qualms gave internal indication of my having swerved slightly from the truth. It was therefore agreed that we should dine here, and I lost no time in sending for my own dinner. My host ordered dinner to be served immediately, and we sat down each to a couple of large trays, one containing a number of small cups with different Burmese delicacies, including pork, which had been arrested on its diurnal tour through the village, and suffered death on the occasion; the other, containing a large blue and white wash-hand bason full of rice. But my own dinner fortunately arrived just in time to save me from a most uninviting black looking piece of the aforesaid unclean animal, which the Mogaung Governor had kindly deprived himself of for my own sake, and torn in pieces with his finger which had been a dozen times half down a mouth and throat if possible less inviting than the savoury morsel, which “for Chesterfield’s sake” I was within an arc of being compelled to eat …

Thus spared the risk of an unpleasant stomach infection, Bayfield was almost immediately urged to assist with a medical complaint affecting one of the escort:

In the midst of the gaieties a man from the Myo-woon came to me in great haste to beg a candle, saying one of the troops was dying, and in a second or two afterwards I heard several voices repeating the Burmese words “Ana-weng, ana-weng.” I went over to see if I could render any assistance, and found the patient sitting up in great alarm amongst a host of anxious faces. On enquiry, I found he had a carbuncle on his back, which for several days had been very painful, but the acute inflammation having gone off he was relieved from pain, and seemed to me to have very little the matter with him. Everybody however said that the disease had “struck inwards”, and that the man would certainly die unless it was brought out again. I proposed treating it secundum artem, and assured them that it was not dangerous, but to no purpose. The man would not submit to the knife, and some bystanders, learned in the Burmese practice on such occasions, prescribed a dose of earth-oil! I tried in vain to save him from such a dose. A small cupfull of the oil, inspissated and thick as treacle, was immediately brought from some adjacent burning flambeaus, and he twice took out at least a table-spoonful, and swallowed it under the usual encouraging exclamations of “Yauk-kya” (that’s a man). I would have preferred the disease to the remedy. In the morning he was as well as ever, having suffered nothing by the dose, and being in statu quo as to the carbuncle. [16]

As the party poled their way upriver towards Bhamo, the evidence started to accumulate of the impact on the riverside communities of the raids of the Kachins, whom Bayfield describes as “a dirty, drunken, dissolute set.” Tsenkhan, which they reached on 8 January, was one of the busiest places seen since Ava but, despite its importance, it was fenced around for protection, just like the smaller villages, against descents by the tribesmen, who periodically made off with its cattle, women and children.

Three days later, beyond Bhamo, they reached the village of Mya-ze-di, which the Kachins had attacked the previous August. It had been entirely destroyed. Bayfield writes,

The Thoo-gyih was killed, and 11 villagers carried off into captivity; five have since escaped, and a negotiation for the release of the remainder at 50 tickals per man is at this moment going on. The local Government never interfere, and no attempt is ever made to suppress depredations, which, beside loss of property, are almost invariably attended by loss of liberty or life. After this attack, the Bamo Governor lent the neighbouring villages ten muskets each, to defend themselves against future attacks, but he has since taken them again to supply the present levy.

Other villages managed to protect themselves by payments of blackmail, but almost all existed in a state of perpetual alarm. At Koung-toun, from which four people had been carried off in a recent raid, one of the villagers gave Bayfield a clear idea of what he thought of his neighbours. They were, he said,

… so dirty, you may write the alphabet on their bodies: they use neither candles nor lights of any kind. Go to bed at dusk of evening like brutes, and follow their young women in droves like dogs. [17]

By the time he reached Mogaung, Bayfield had seen a few Kachin for himself and, echoing Hannay’s earlier description, he gives his own opinion:

In the vicinity of these people there is no security for the traveller or small village. I saw some of them at Tsimbo on the way up. They wear a blue cotton dress with red stripes, and their hair, which is generally very thick, is combed straight over their foreheads, and cut clear off on a level with their eyebrows, giving them a scowling, savage appearance. They are exceedingly dirty, and much addicted to drinking. Their language is peculiar; in their plunderings they respect neither age nor sex, of which many of their inhabitants both of Mogaung and elsewhere are melancholy proofs, and there is scarcely a village that has not some scarred victim.

Mogaung, the principal town in the area, and the centre from which the jade trade was meant to be supervised, was beset to the west by the Tsam-paran Kachins “who go nearly naked and cut their hair short, and are more dreaded than any other”, and to the east by the Eethee-Kachins “who are the terror of the whole western side of the Irrawaddy from a short distance above Kalha.” It was near here that, on 19 January, a party of thirteen of the Daffa Gaum’s people, who were bringing buffaloes to support the expedition, were attacked, with the loss of eight killed and all the supplies.

By now, the Myo Wun had become exceedingly nervous. He implored Bayfield to halt, to enable him to marshal fresh supplies and a fuller escort. But Bayfield knew the rains were approaching and that time was pressing if he was to make his rendezvous. On 26 January, having lost a week of time to no effect, he pushed on, leaving half his baggage, his tent, and a host of wondering officials behind him on the riverbank. If he cleared the trail, he thought, the Myo Wun’s supplies might catch up with him before his party became desperate.

Two days later, he reached Kamein (Kamaing). The following night, the Burmese escort joined him, but without supplies, and Bayfield was obliged to intercede for some Shan fisherman who curing their catch on the riverbank. They would have lost the fruit of their labours, had he not done so.

At the halting place for 1 February, Bayfield encountered a party of Kachins crossing the mountains to demand reparation from a neighbouring chief. This was for an outrage committed the previous year, when his people had been employed in clearing the way for the Myo Wun and Capt. Hannay’s party. In the subsequent affray, eight of the Kachins’ dhas had been stolen, but despite the passage of time, and a promise that the knives would be restored, the insult had not been forgiven. To spare their honour, the Kachins demanded in addition a slave, and this had been refused. Bayfield attempted to persuade them to submit their dispute to the Myo Wun’s arbitration, but he suffered from no illusions that they would do so; indeed, he was convinced the quarrel would “most likely be continued through many generations”.

The trail from Mogaung to Maing Khwan, the point from which the expedition of the previous year had returned, was 108 miles and followed a path through dense jungle and across multiple rivers. Some of these had to be crossed twenty or thirty times and, when they were, Bayfield and his party were frequently soaked to the waist. Later, in his diary entry for 4 March, Bayfield was to write of one part of his journey,

The river runs between hills varying in height from 200 to 1,000 feet, densely covered with forest to the water’s edge, and apparently uninhabited. There is no road, and the route, which is along the stony bed of the river, is rendered both difficult and painful by the stones and angular masses of rock, in many instances covered with wet moss, upon which a footing is with difficulty maintained. We have suffered much from the leech and dum-dum bites; of the former I had no less than 120 on my feet and legs, which in consequence were swollen and painful. The itching occasioned by the bite of the dum-dum is intolerable.

The result of all this hardship was that, by the time the Myo Wun and Daffa Gaum next caught up with Bayfield’s party (once again without provisions), he and a number of his men were falling sick. In his journal entry for 8 February, he writes:

We have not yet received a single basket of rice beyond the little procurable in the village … so that the people are literally half-starved … and subsist upon young leaves, gathered in the neighbouring spot of forest, and boiled with some rotten fish and salt, dignified with the name of gnapie … Three of the poor fellows have died, many have fevers … Indeed, it is really pitiable to hear the incessant coughing during the whole night, and to witness the state of misery and want now existing among them.

The progress continued, Bayfield and a portion of the party in the vanguard, the Myo Wun, the Daffa Gaum and the remaining escort hanging back until, eventually, after more than seventy days of travel, the junction with the contingent travelling from Assam was achieved on 5 March 1837. (Major White had, just a few hours previously, been obliged to leave because of a Singpho threat to supply points in his rear).

Two days later, the Myo Wun caught up again. Griffith recorded his first impressions of him as follows:

March 7th – To-day the Meewoon arrived accompanied by perhaps 200 people, chiefly armed with spears; he was preceded by two gilt chattas. He made no objections to my remaining, and really appeared very good-natured. The first thing he did, however, was to seize a shillalah and thwack most heartily some of his coolies who remained to see our conference. He did not stay ten minutes.

Before he departed, Major White had given Hannay the charts that he could show the governor, to fix the boundary. This was done on 9 March, at a stream in the Lwe-pet-kai mountains, which Bayfield calls the Nam-yang Nullah. Three days later, Hannay returned to India. Bayfield says that, expecting to find assistance at the frontier (which did not appear), he had brought insufficient provisions to continue. But, following the contretemps that his earlier appearance had caused at Ava, we can assume he had no desire to return there and, anyway, he will have been interested to explore Sepoy Singh’s track to Assam. Griffith, it was decided, should travel with Bayfield to Ava.

After a few more days, the rains started in earnest, and Bayfield became impatient to be gone. On 13 March, he reiterated to the Myo Wun his responsibilities under the boundary agreement and announced he was leaving.

If he thought that would be the end of the matter, however, he was mistaken. Three days later, the governor caught up with him and announced he had received fresh instructions from Ava, to the effect that the frontier was not in the Lwe-pet-kai after all, and that (to use Bayfield’s words) he was to advance “into the heart of Assam with an armed escort of 1,000 men”. No doubt that is an exaggeration, but it was only with considerable difficulty that Bayfield persuaded the governor of the certain consequences of his doing such a thing. Eventually, the Myo Wun backed down and settled for what had been agreed earlier, upon the condition that Bayfield would provide a positive report on his conduct to the Burmese government. Then, after an exchange of some “trifling” presents, they separated for a second, and final time. [18]

Of these events, Griffith makes no mention. His journal contains nothing but notes on the flora and fauna. He had been told that the hills had potential in the production of tea, but he found no evidence of it, and concluded that anything sourced from the area under that name had to be “a spurious preparation”. For his part, Bayfield organised discussions with several village sawbwas, in which he attempted to persuade them of the benefits of opening a commerce with Assam, after which he concluded, “of the practicability of opening the communication I entertain no doubt but of the immediate profitableness, considerable.” [19]

As a first step, he suggests, the Kachins would have to be roused “from the extreme of indolence to industry”, but he hoped that, with time, the introduction by merchants of the necessities and then the luxuries of the civilised life would have their effect. Meanwhile,

The only return that could now be made is a small quantity of gold dust, possessed by but a few people, and an equally small quantity as to value of ivory. I have seen no other cattle among them than buffaloes, and these are very dear, and would not, I should think, even if the Singphos would sell them, be a profitable speculation.

I omit amber and serpentine stone for the present, because, even if suited to the European market, I would not at first advise an interference with that trade, for fear of exciting the jealousy of the Chinese, Shans, and Lapaes (the most numerous of the singphos), who have the monopoly of it, and consequently possess much influence with the local offices and Men-tha-gyih Prince, who derives a considerable revenue from them, and would be sure to take alarm at so novel an event. The trade being secured about and near the frontier, should there be any body to trade with, would in a very few years spread throughout the country, and be beyond the power of Burmese control.

In short, Bayfield’s opinion was that the Kachins were too independent-minded and too unruly to be interesting counterparties:

The Singphos have no acknowledged Chief, each Tsanbwa (sawbwa) is the independent head of his own village, and attacks his neighbours if aggrieved or thinks he can do so with success. They have no written language or system of jurisprudence to appeal to; each has his own avenger. They are said never to forgive an injury, and feuds are consequently kept alive from one generation to another. Although within the Burmese dominions they pay no revenue and are subject to no sort of control, the Burmans in fact fear them, and never go among them except on special occasions and in well armed, large parties.

In addition, their experience of the British was unfavourable. Several of those with whom Bayfield discussed the causes of the wars between the tribes attributed them to opium and spirits, which they said had spread across the border from Assam. Bayfield, attempting to salvage British honour, suggested that, if this was so, it was likely that Assamese captives, transported to Burma before Britain’s occupation, were responsible. Whether he believed this or not, however, it was undeniable that every village through which he passed had its plantation of poppies, and that, aside from the rice, cotton and pumpkin, which were grown to satisfy the villages’ immediate requirements only, opium seemed to be “the only cultivation of the country”.

On 25 March, the travellers reached Maing Khwan, from where Hannay had made his earlier visit to the amber mines. Griffith describes it a large, well-stockaded and divided in two by a small stream. Nearby there were some decayed pagodas and a “Poonghie house” (monastery) around which were planted some mango trees and a large bauhinia, which he named for his travelling companion. The mines themselves were judged too much of a hit and miss affair to be commercially attractive, and they did not detain them long. Griffith writes,

The pits are square, about four feet in diameter, and of very variable depth. Steps, or rather holes, are cut in two of the faces of the square, by which the workmen ascend and descend. The instruments used are wooden-lipped with iron crowbars, by which the soil is displaced. This answers very imperfectly for a pickaxe …

We could not obtain any fine specimens; indeed at first the workmen denied having any at all, and told Mr. B. that they had been working for six years without success. They appear to have no index to favorable spots, but having once found a good pit they of course dig as many as possible as near and as close together as they can …

Bayfield adds the detail that the pits were abandoned during the rainy season between April and October as, in this period, they emitted an offensive gas, in which lights would not burn, and which was “destructive of life”. The workmen appeared to him to be “emaciated and sickly”, but he says that they denied that anything to do with their employment was the cause.

By 1 April, the travellers reached Kamein (Kamaing), “a mean and paltry town”, sited at the junction of the Indaw and Mogaung rivers. By now, the bearers were growing apprehensive about their journey. Indeed, two of them decamped that night, and Bayfield mentions that he and Griffith had already been forced to leave behind their tent, for want of carriage. In lieu of this, the welcoming headman of the village had a small shed built for their accommodation. And when they mentioned their intention of visiting the mines, he put up only “slight opposition”. A guide was obtained, and they departed at ten o’clock the following morning.

The journey took three days. According to their description, the valley in which the jade was produced was about twenty miles long, semi-circular in form and just a few hundred yards wide. A small streamlet ran along its length between what had once been low, rounded hillocks, but it was now much choked up the spoil of the excavations. Jade was to be found along the whole length of the valley, as well as along the banks of the Uru river, into which the streamlet flowed. Bayfield writes,

The pits are neither regular nor deep and, unlike the amber mines, there is nothing to guide the laborers in their search; many are consequently employed for months and get nothing. The stone is found from ten to thirty feet below the surface in rounded masses or boulders, water-worn and mixed up with similar masses of rocks …

The largest masses are not above four maunds, and in external appearance have nothing to distinguish them from many others with which they are found, and until broken it cannot be determined whether they will be valuable or not. In order to facilitate the fracture, the mass is thrown into a strong fire, and when thoroughly heated, a heavy stone is thrown violently upon it and it readily separates.

He added that the best sort of jade was becoming increasingly scarce and that, as a result, a good portion of the stone that was now being bought by the merchants would not previously have found a purchaser. That year, he was told, there had been six hundred visitors to the mines, the vast majority of them labourers, and very few of them significant purchasers. In 1836, the duties charged at the rate of thirty-three per cent had raised 220 viss of silver, equivalent to twenty-five thousand rupees. In the current year, it was expected to be rather less.

Griffith mentions that he and Bayfield were unable to obtain any good specimens of jade, and he says Bayfield told him that the previous year’s revenue was 320 viss of silver (Rs. 40,000), which was evidently a misunderstanding. Otherwise, he was clearly dissatisfied by what he saw, suggesting that, in the absence of any machinery, there was nothing that repaid the effort of making the journey, although he adds that the importance of the trade was made evident “from the fact that B. counted, since we left Camein, 1,100 people on their return, of whom 700 were Shan Chinese”.

The visit itself turned out to be not the only disappointment, for on their return to Kamein, the welcome of the village headman was quite transformed. Earlier, before they visited the mines, he had shown himself to be “particularly civil”, but now, when they were on the point of embarking for Ava, he was found to be unloading their baggage and even carrying away one of their canoes. When Bayfield intervened, the Chief, “foaming with rage” and “distributing abuse all around in the most liberal manner”, told him he should not have it “even for a viss of silver”:

His passion was unbounded and apparently uncontrollable, for as he spoke he drew himself up to me in so threatening and insolent a manner, that I was compelled to put forth my hand and push him away. This, however, was an act for which I was near paying dearly, for himself and one of his followers instantly drew their swords and flourished them about in so ominous a manner, cutting up the grass and earth within a cubit of my feet, that for a minute being totally unarmed, I considered myself in some jeopardy.

It transpired that the chief had been summoned to Mogaung the instant the news reached it that Bayfield and Griffith had gone to the serpentine mines. There he had been accused of accepting bribes of some broadcloth and a viss of silver in order to let them go. The consequence was that, although the chief’s anger eventually abated, he was not to be moved on the use of the boats, and the twenty-five miles to Mogaung had to be taken on foot. [20]

Worse, when they got there, on 9 April, Mogaung was in lock-down. The King in Ava had been deposed by his brother, the Tharrawaddy Prince, and, in the aftermath, court and countryside were descending into anarchy. Earlier, a residency boat sent by Henry Burney with despatches for Bayfield had been attacked by insurgents. An American missionary, Rev. Kincaid, had been aboard it and he had been robbed of all he possessed by the Prince’s troops. Now, Bayfield learned, he “was said to have been captured by some roving bands of the Serrawaddy Prince’s force and murdered at Tsa-ba-na-go”. [21]

For his part, the Myo Wun had been abandoned by the majority of his troops (parties of whom were passing to the east of the town “firing off their muskets in a most disorderly manner”) and by the Daffa Gaum “who refused further obedience … and declined accompanying him to Mogaung, as ordered to do.”

Deciding that to seek safety by crossing to Assam would be just as perilous as staying where they were, the Englishmen hunkered down until, on 19 April, they made a break for it, taking a boat and trusting their lives to the Irrawaddy. They eventually reached Ava on 15 May, after an absence of five months and two days, only to be told that the residency was being closed and the British were retreating to Rangoon. [22]

In the period since Bayfield’s departure, the ministers at Court had become increasingly suspicious of the purpose behind Hannay’s going to Calcutta and returning to Ava by the northern route. Indeed, a report became current that the British were collecting a force in Assam with a view to taking possession of the whole area to the north of Mogaung. Henry Burney was unable to convince the Burmese that this was not the case, even though he presented them with a Government of India declaration that “our objects are only to promote a safe intercourse beneficial to both states, and to ensure sufficient protection to the tribes under our authority”. This, however, was not the reason for the coup d’etat.

By the time of the Griffith and Bayfield mission, King Bagyidaw, who had ruled Burma during its war with and defeat by Britain, had become beset with depression. Tharrawaddy, the King’s only true brother, became one of four commissioners appointed to act on the King’s behalf during his incapacity. However, real power was in the hands of the Queen, Mai Nu, and her brother, the lord of Salin, the Minthagyi, or “Great Prince”. Both were of low origin and detested by the rest of the royal family, and Tharrawaddy became convinced that the Minthagyi aimed at usurping the throne. In February 1837, things came to a head when the Minthagyi seized some of Tharrawaddy’s supporters and put them in irons; Tharrawaddy collected troops and, following the tradition of his house when seeking a change of government, left Ava for Shwebo, the original home of the dynasty.

To Henry Burney, who, for several weeks, acted as mediator between the contending parties in an attempt to prevent the carnage which often accompanied Burmese transfers of power, the Court’s failure to resist Tharrawaddy was quite mysterious. Their strength was overwhelming, but they lacked a leader, and the troops sent to deal with his force never got within miles of it. As a consequence, Tharrawaddy became caught up with his “extraordinary success”. He liked Burney personally, but decided the residency was a humiliation he could do without.

At a final meeting with Tharrawaddy on 9 June, which Bayfield also attended, Burney and he had a talk about the dispute over the Assam-Burma border. Burney argued the ancient history of Assam supported the boundary fixed by the British. Tharrawaddy responded by saying histories were unreliable as they were human compilations:

[He said] “that the limits of every country are marked by certain natural appearances, and that the boundaries of Burma in every direction are well known by the trees on the frontier growing in a very peculiar manner, those within Burmah growing with an inclination towards Burmah, and those within their neighbours’ territory bending towards that territory”.

To this neither Burney nor Bayfield were able to produce a convincing reply. They therefore departed, even as Tharrawaddy was heard requesting Burney to procure him some gardeners and some fire engines from Calcutta. [23]

After the Third Anglo – Burman War

In the era of Victorian expansionism, rebuffs of this sort were not accepted for long by the British. Whether in Burma, or in China, business was clamouring for an opportunity to capture new markets, and in both, the consequences were similar: the Second and Third Anglo-Burmese Wars of (1852-1853) and (1885-1886) and, between them, the Second Opium War (1857-1860), which culminated in the looting and burning of the Qing’s Summer Palace in Peking.

The British, of course, did what they could to absolve themselves of the responsibility for this particular episode; it was, they said, the French who were more culpable. As Capt. Charles “Chinese” Gordon put it “these palaces were so large and we were so pressed for time, that we could not plunder them carefully … The French have smashed everything in the most wanton way, it was a scene of utter destruction, which passes description.”

Whatever one makes of such claims, the significance of the event for us is that, as a result of the looting, large quantities of Burmese jade made their way for the first time onto the international market. Heber Bishop, a sugar mogul with a particular appetite for the stuff – his thousand-piece collection was donated to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1902 – wrote in his huge limited edition book Investigations and Studies in Jade that “many objects had found their way into the shops of dealers in antiquities … but many were still held by members of the expedition. I found some pieces had been carried to Frankfort, Amsterdam, Dresden, Berlin and Vienna. At St. Petersburg, Moscow and Constantinople I also obtained some beautiful specimens that had come out of China.” [24]

The behaviour of the British at the fall of Mandalay, in 1885, was perhaps slightly less abject than it had been in Peking, but there was significant looting and several boxes of effects, including King Thibaw’s crown, a solid gold figure of Buddha, and boxes of jewels and jade found their way to Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. Other items, including a fine model of the royal palace and, conceivably, the state bed of King Thibaw and his queen, were used to decorate Clandeboye, the home of the Indian viceroy, Lord Dufferin. Rather more was seized upon by the officers and men of the expeditionary force; so much, indeed, that they found it impossible to transport it home, and much of it soon appeared for sale in Mandalay’s streets. Colonel Willoughby Wallace Hooper, a keen amateur photographer, noted in a caption to his photograph of The Interior of a Phoongye Kyoung that “the contents of the room in the picture here given consist principally, as is seen, of what may be designated loot.” [25]

There also arose the matter of a concession to some ruby mines in Mogok.

In 1883, these had been assigned by the Burmese to a Frenchman but, now Captain Aubrey Patton, whom Randolph Churchill described as “an adventurous speculating person, known to fame for his great proficiency in pigeon shooting”, claimed he had obtained it. Two sets of jewellers, one in London and one in Calcutta, also had an interest. The controversy generated considerable heat in the House of Commons, although the Burma Commissioner, Sir Charles Crosthwaite, thought it certainly didn’t deserve the attention it received. With rebellion spreading in the countryside, he regarded the idea of sending an expedition to occupy Mogok, as something akin to “a man polishing the handle on his door when his house is on fire.” It did go to show, however, that the people on the ground were alert to the mineral wealth around them, and although it was known that the Kachins “even owed the Burmese government very little authority in respect of the jade mines”, it was little surprise that, in December 1885, it was decided to send a force to Bhamo, which lay en route. [26]

At first, the British managed to establish themselves reasonably well, despite the monsoon, which brought with it dysentery and cholera. The local Shans, says Crosthwaite, “were peacefully inclined, though shy and timorous” and the Chinese traders, “although they disliked exceedingly our interference with the opium and liquor traffic, and even more our attempts in the interests of the troops to improve their methods of sanitation”, were not actively hostile. Outside Bhamo, however, the situation was rather hotter, as the Kachin “began to show their teeth and to do their best to make things unpleasant.”

In Mogaung, Maung Kala, a man of local influence who had been appointed magistrate in the British service, was assassinated. He was replaced by his son, Po Saw, “in consequence of his having summarily executed a pretender who had endeavoured to impose himself on the people.” It was peace of a sort, although it would have been extravagant for the commissioner to claim jurisdiction, as it was thought the tranquillity of the district would have quickly evaporated, had any attempt been made to collect the revenue. A stockade was built at Sinbo (Tsinbo) but, beyond that, nothing more was done until extra resources could be brought to bear. [27]

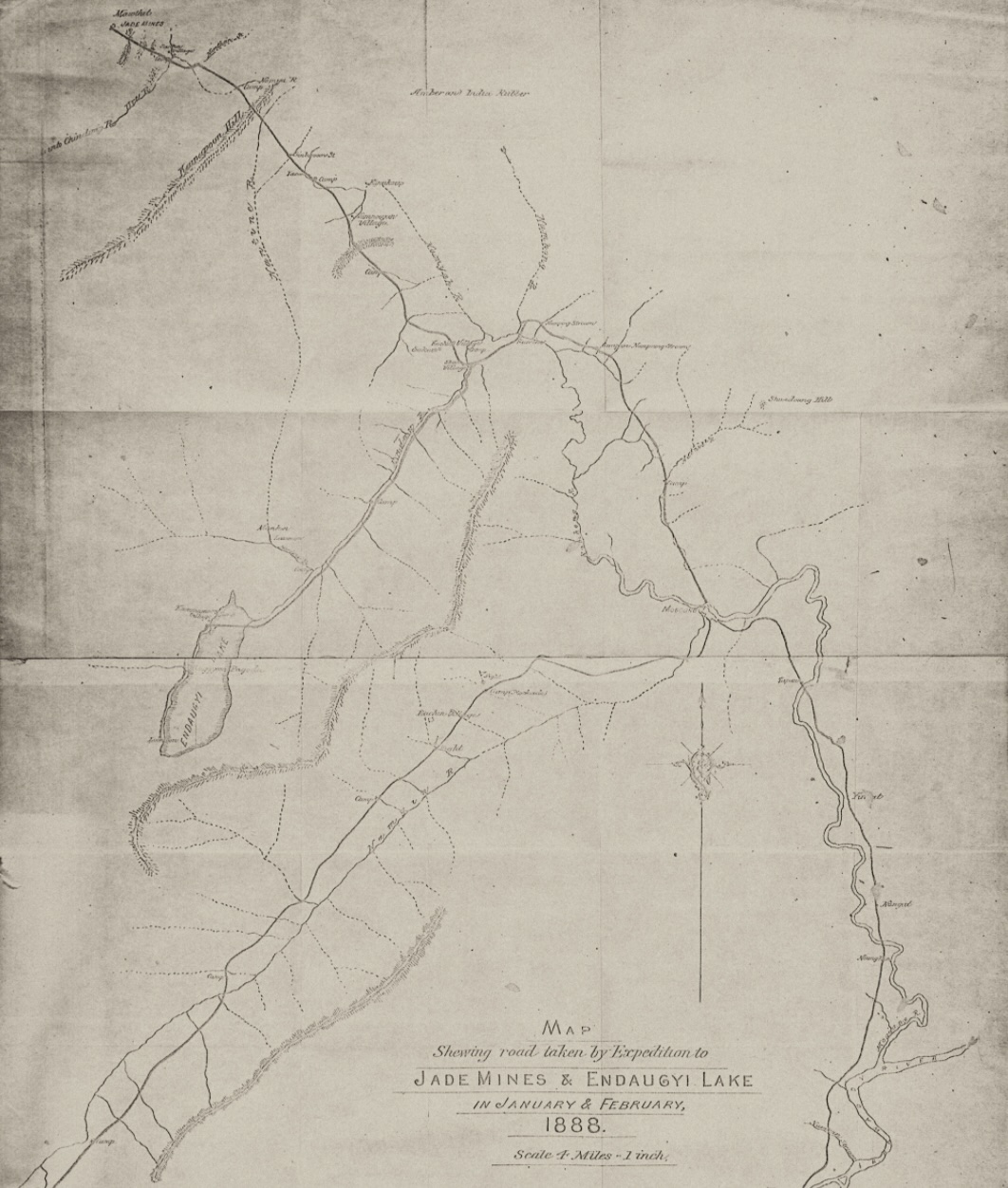

Eventually, in November 1887, Po Saw was instructed to clear the route to Mogaung and to bring the Kachin leaders connected with the jade mines to meet the British there. Major Charles Adamson was put in charge of a force of just under seven hundred hundred rifles and two mounted guns. On land, the baggage train consisted of 350 mules, and on the river, they were accompanied by three steam launches and thirty-three large country boats. Little, apparently, was being left to chance. On 27 December, the expedition left Bhamo.

Inevitably, beyond Tsinbo, the guides proved false and the trail was not properly prepared. As they entered an unknown area dominated by a Kachin chief from whom the inhabitants had to purchase protection, the British were met by Mr. Rimmer, a commander in the Irrawaddy Flotilla, who was coming the other way with Lon Pein, a Chinese from Canton, who had been the farmer of jade under the Burmese king and to whom the British had re-let the rights in early 1887. He had been badly wounded in the head. He and Rimmer had escaped from Mogaung where, on 10 January – to use Costhwaite’s words – “a body of ruffians besieged [their] house with more vigour even than the police led by the Home Secretary against the house in Sidney Street.” [28]

Mogaung, when they reached it, reeked of the arrack being distilled by the Chinese traders. “Whatever the Indian Temperence Society may think”, wrote Crosthwaite, “we cannot be accused of introducing alcohol or the vice of drunkenness into these regions.” And no wonder it was popular; the townspeople were living in dread of the Kachins, and spent as much time sleeping in the safety of an island in the middle of the river, or on their boats, as they did in their own homes. [29]

After a ten-day halt, during which it constructed a fort and stockade, the force next departed for Kamaing. When they reached it, on 30 January, some remaining monasteries and pagodas showed how it had once been flourishing, but now they were deserted and only a few houses of the poorest description remained, the place having suffered heavily in a Kachin rebellion against the Burmese, in 1883. Adamson received a friendly welcome from the village elder, but messages from the jade mine sawbwas advised him that the expedition would do best to remain in Mogaung. Since the suggestion had already been superseded by events, Adamson instead pressed ahead to a crossing on the Indaw River, where he established another defensible post. Then, with a smaller fighting column, he pushed onward, encountering along the way a variety of sawbwas, who were friendly enough within the confines of their own territory, but whose guides proved most reluctant to advance beyond them.

At last, on 6 February, some messengers arrived from the principal jade-mine sawbwa, Kansi Naung. They invited the British to a conclave on the Uru River, where there was fodder and water in plenty. The watershed between the Chindwin and the Irrawaddy had to be crossed. The rain fell and the mud reached the bellies of the mules but, when eventually they reached the rendezvous, the expedition found a “beautiful stream … as clear as crystal, and alive with fish, which kept rising to the surface in the evening, like trout in an English stream.”

Kansi Naung failed to show – it was said he had dysentery. Adamson, who had received news that Po Saw and several hostile chieftains were in the vicinity and were urging resistance, became anxious. A guide was asked to deliver a message, but he refused to go, saying he knew the Kachins were on his track to murder him (in which suspicion he was not wrong – as later events were to prove). Adamson writes,

Up to this time Shwe Gya had been most happy and cheery, full of anecdotes, and confident of success. Now, owing to the failure of Kansi Noung to come in, according to his promise, he was most despondent, thinking I would lose confidence in him and that, as he expressed it, his face would be blackened before me. I tried to cheer him up, but it was of no avail. As he had far better means than I had of knowing what was going on, I was very much disturbed, and I thought things looked very serious.

Adamson decided that, if he delayed, his position could only worsen, and that he should capitalise as soon as possible on the nervousness that the arrival of his column had inspired amongst those of the chiefs that had most to lose in the event of hostilities. He issued an ultimatum. If the chiefs did not appear by ten the following morning, the column would advance to the jade-mines by force. At nine, Kansi Naung and twelve other chiefs appeared on the opposite side of the Uru River, behind a man bearing a fine pair of elephant tusks. The British troops, drawn up for a hostile advance, instead formed a square of honour. The tusks were presented, and “all the Merip Sawbwas … joined in the submission.” Adamson wrote,

I have never in my life experienced such a feeling of relief as when I made out what was happening … As it was, and as it has been in all our dealings with natives in India and Burmah, “brag” carried the day. If it were not for “brag” I do not know how we could have conquered India. “Brag” on the part of the leaders, which is bred of confidence in the pluck of the soldiers, had in this case proved successful, and Kansi Noung had not dared to oppose us when he saw that we were determined to go on in spite of him. [30]

The following morning, the troops fell in and started for the jade-mines, which were reached after an uneventful march along a rough forest path, which nevertheless rose to fifteen hundred feet. There was not much to see: beyond the encroaching jungle and the dry bed of a stream, just “a collection of about fifty houses and what appeared to be a large quarry, while all over the place were blocks of white stone of all sizes, some of which were tinged or streaked with green.” All the same, Adamson was delighted:

With the exception of Lieutenant Bayfield, who about the year 1838 had managed to reach one of the mines, no European had ever been allowed to see them. We were absolutely looking at those mines which, to the Chinese, have from time immemorial been considered to be the most valuable possession in the world – we were looking at them, not in the position of persons who were permitted by favour to such a high privilege, but as those who were there by right, and who had come to take possession of their treasures for and in the name of the British people.

But it was not to prove as simple as that. Immediately, disquieting letters came from Mogaung. Perhaps emboldened by his success, Adamson was not unduly concerned, at least to start with. For a few days he took his squadron on a tour of the Indawgyi Lake, which he found had been transformed from a thriving and populous plain into a desert during the 1883 rebellion. For his pains, he also spent an uncomfortable night during a storm on the narrow spit of land that connects its famous pagoda to the western shore. Then, on the return march to Mogaung, his column was attacked repeatedly by the Kachins, who had fortified posts along the road. Although these were quickly dealt with, two or three of Adamson’s men were killed. Nor, when he got there, was the state of affairs in Mogaung reassuring. Crosthwaite now takes up the narrative:

The people were in much alarm. Women and children were sleeping in the boats. The road was unsafe, and communication with the Irrawaddy was interrupted. The last boats which had left the town with the mails and some prisoners under guard, had been fired on by the Kachin; and a boatman and one of the Gurkha police were hit. No Chinese boat had ventured up the river for three weeks. The resident Chinese were putting their temple in order of defence, and everyone expected there would be fighting.

They weren’t wrong. Adamson returned to Bhamo, but there was no shortage of evidence of Po Saw’s activity. He had joined with Bo Ti, whom Adamson had previously arrested but who had since managed to dig his way out of the prison in the town. “The two together were powerful for mischief”, says Crosthwaite, “and it would have saved much hard work and many lives if they had been shot in the beginning.”

The first news was of their pressuring the villagers of Taungbaw to assist them in attacking Mogaung. To the British, the Taungbaw headman proposed they prepare an ambush. The acting commander, Lieutenant Elliott, thought this “a treacherous dealing a British officer ought not to countenance” which, to Crosthwaite, was “a piece of high-minded chivalry somewhat misplaced under the circumstances”. Bo Ti was allowed to establish himself and it took a full assault by the Gurkhas to dislodge him. It set the pattern for a brutal campaign that extended into 1889. The British called up artillery and Gurkha reserves and, by the end, their column had engaged with the Kachins thirty-two times and taken forty-six stockades in an offensive that extended over 650 miles.

At the end of his account, Crosthwaite suggests that “by the occupation of Kamaing, the trade route to the jade mines was opened and made safe” and that “villages from the Kachin tribes came in by scores to make formal submission to the Assistant Commissioner at Mogaung”. However, he had to admit “Thama and two others continued to hold out” and, in 1904, the Comptroller of Assam, looking back on the Myitkyina “of a dozen years before” described it as “the ultima thule of Burma, a military outpost in the heart of the enemy’s country [which] had to look out for itself, feed itself, and fight upon occasion for its life, [and which] one winter was attacked and burnt down by the caterans of the hills over the heads of its garrison of a thousand men.” [31]

Even as late as December 1914, when reports spread that the British troops were being sent away to be massacred by the Germans on the Western Front, there were further uprisings in Mogaung and Kamaing led by the headman from Thama, and Walabum Gaum and the Duwa of ‘Ngan in the Hukawng valley. In due course, these outbreaks were quelled, and the chiefs sentenced, but the leader in Myitkyina, who was also arrested, was described in the official report as “an irreconcilable who led an attack on Myitkyina as far back as 1892.”

In respect of the Mogok ruby mines, Commissioner Crosthwaite had written that “as a source of revenue they were of no great moment, and if we had left the native miners alone we should have saved the heavy expense of maintaining a strong force up in the hills and making a long and costly road … through thick jungle, poisoned with malaria and … infested with dacoits.” In truth, the British did no better out of the jade trade.

In 1934, in his book The Mineral Resources of Burma, HL Chhibber provided some clues as to why this might be. “It is noteworthy”, he says, “that in sales and valuations prices are not mentioned openly, but are indicated by a conventional system of finger pressures under cover of a handkerchief.” Limited scope, then, for the British to assess and claim their cut. He then proceeds to quote Major FL Roberts, formerly Deputy Commissioner, Myitkyina:

From the time jade is won in the Jade Mines area until it leaves Mogaung in the rough for cutting there is much that is underhand, tortuous and complicated, and much unprofitable antagonism. In my opinion, the whole business requires cleansing, straightening and the light of day thrown on it.

Worthy sentiments, no doubt, but not a plan that met with any great effect.

It was only a few years later that the Kachins found themselves defending their homeland as vigorously against the Japanese as they had against Major Adamson. By then, they were friends to the British and their exploits with Wingate and Calvert’s “Dahforce” earned them the honoured sobriquet of “The Amiable Assassins”. As Bernard Fergusson put it, “We came into that country ragged, sick, weary and wholly unimpressive; yet we were received, sheltered, fed, led and hidden with all the devotion of Highlanders after Culloden.” Yet, when the fighting was over, the Kachins were abandoned (“a lamentable page in our history”) and, after independence, they were pushed to the new country’s margins, as a new set of interlopers seized control of the green treasure in their hills. [32]

After the 2015 elections, the new democratic government of Myanmar promised a federal constitution along the lines of the Panglong Agreement to which the Kachins were signatories in 1947. Progress was difficult, slow and inconclusive. Since then, the military coup of February 2020 has pushed all such considerations right off the agenda. The latest reports of the state of affairs in the country make for disturbing reading. Such is the wealth of the mines and the greed inherent in human nature, that one wonders whether the Kachins will get equitable treatment any time soon.