“Herring Boats”, or something more formidable?

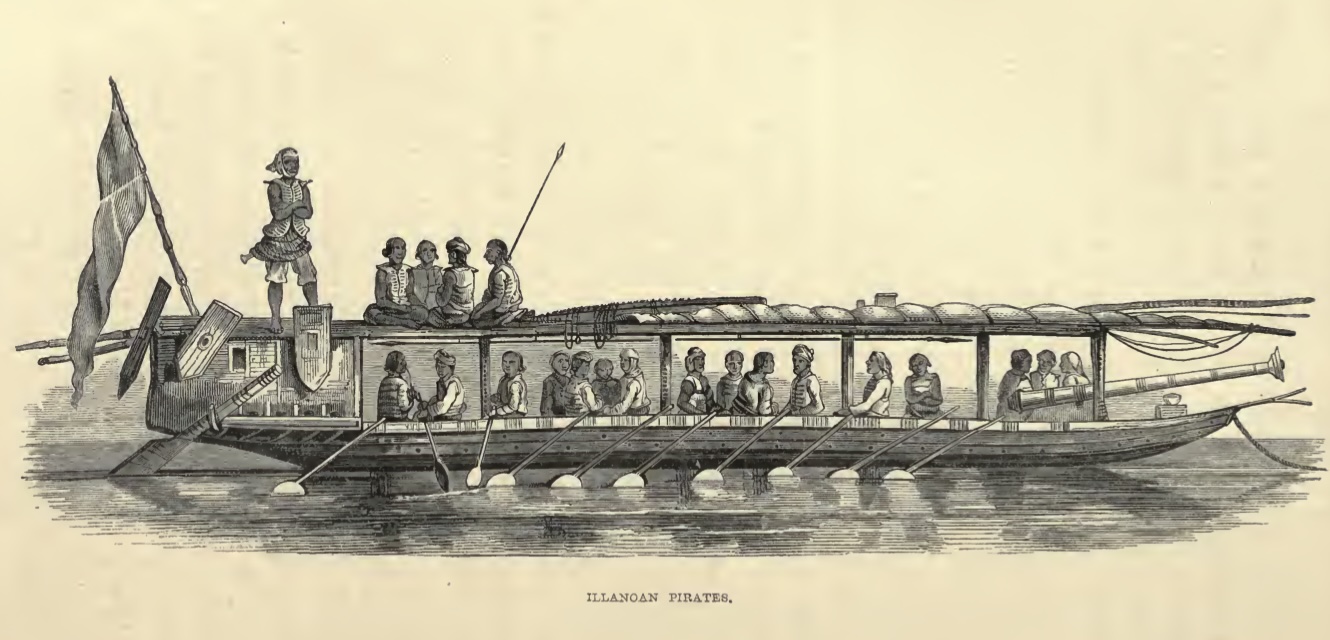

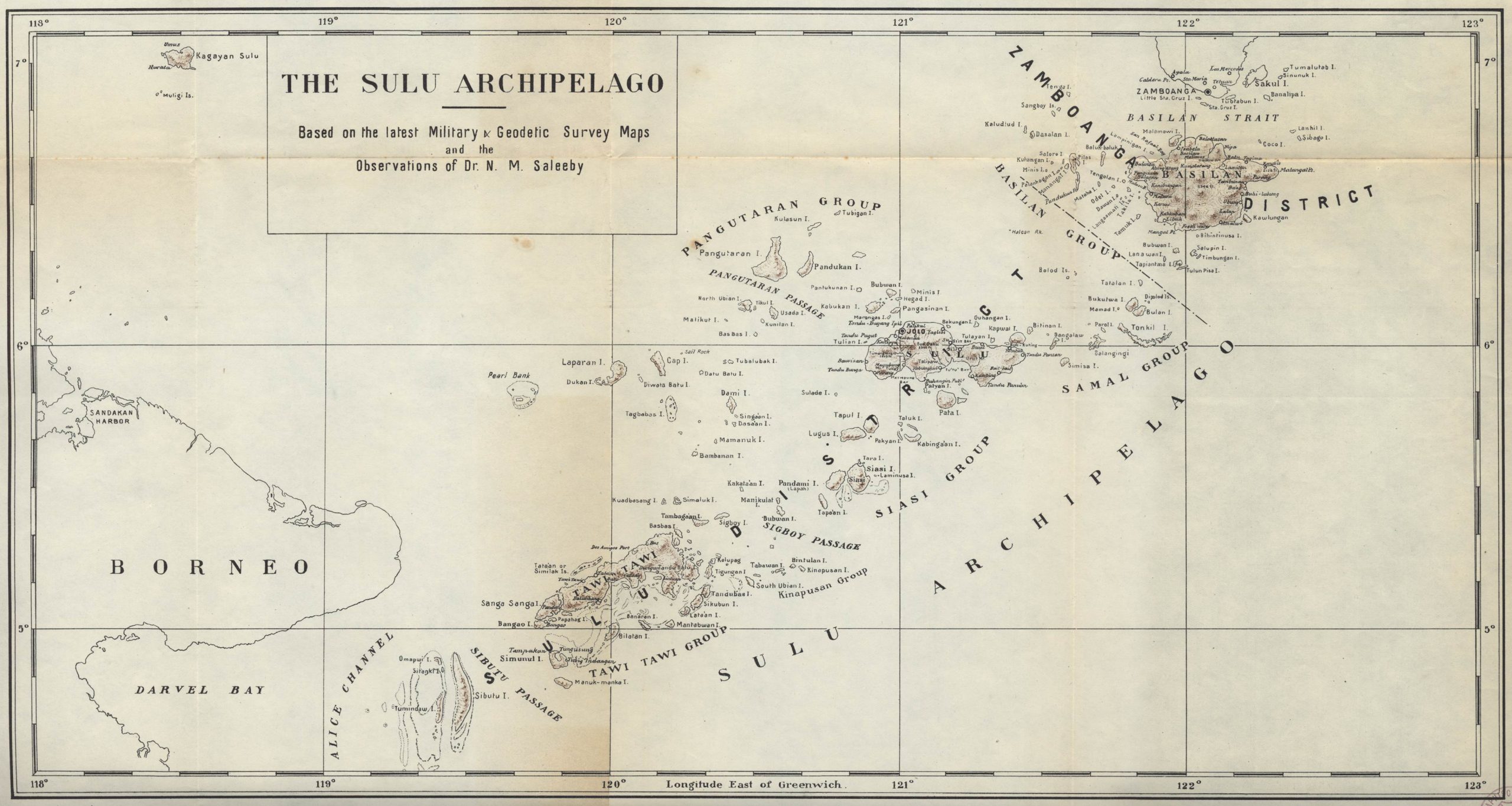

In and around the Sulu Archipelago, there were two principal pirate groups; the Illanuns, whom the Spaniards called los Moros or los Illanos de la Laguna after their stronghold off Mindanao, and the Balanini, whose settlements were on the islands of the archipelago itself.

Possibly the earliest description of an Illanun prahu is by Thomas Forrest, who saw one return from a raid to Mindanao, in July 1775:

On 31st, came in a large prow belonging to Datoo Malsalla … from a cruise on the coast of Celebes. She had engaged a Dutch sloop, and was about to board her, when the Dutch set fire to their vessel and took to their boat. Notwithstanding the fire, the attackers boarded her, and saved two brass swivel guns, which I saw, and even some wearing apparel. The vessel being hauled up, I had the curiosity to measure her. She was from stem to taffel 91 foot 6 inches, in breadth 26 foot, and in depth 8 foot 3 inches. Her stern and bow overhung very much what may be called her keel. She steered with two commoodies or rudders; had ninety men, and could row with forty oars, or upwards, of a side on two banks. The manner was this: the twenty upper beams, that went from gunnel to gunnel, projected at least five foot on each side. On those projecting beams were laid pieces of split cane, which formed a gallery on each side the vessel for her whole length; and her two ranks of rowers sat on each side, equally near the surface of the water, the two men abreast having full room for their oars, which are far from lying horizontally, but incline much downwards. This vessel brought to Mindanao about seventy slaves. [2]

Writing of the Illanuns in the 1840s, Sir Edward Belcher, captain of HMS Samarang, was in no doubt of the threat they posed. He explained their vessels,

… are very sharp, of great beam, and exceed ninety feet in length; they are furnished with double tiers of oars, and the largest generally carry about one hundred rowers, who are slaves, and not expected to fight unless hard pressed. The “fighting men”, (or chiefs) as they are termed, amounting to thirty or forty, occupy the upper platform, and use the guns as well as small Leilas or swivels. The whole of the main interior occupying about two-thirds of the beam, and three-fifths of the length of the vessel, is fitted as a cabin; it extends from one-fifth from forward, to one-fifth from aft, and at the bow, is solidly built out to the whole beam of the vessel, with hard wood baulks of timber, calculated to withstand a six-pounder shot: a very small embrasure admits the muzzle of the long gun, which varies from the six, to a twenty-four pounder, generally of brass; independent of numerous swivels, of various caliber, mounted in solid uprights, secured about the sides and upperworks of the vessel.

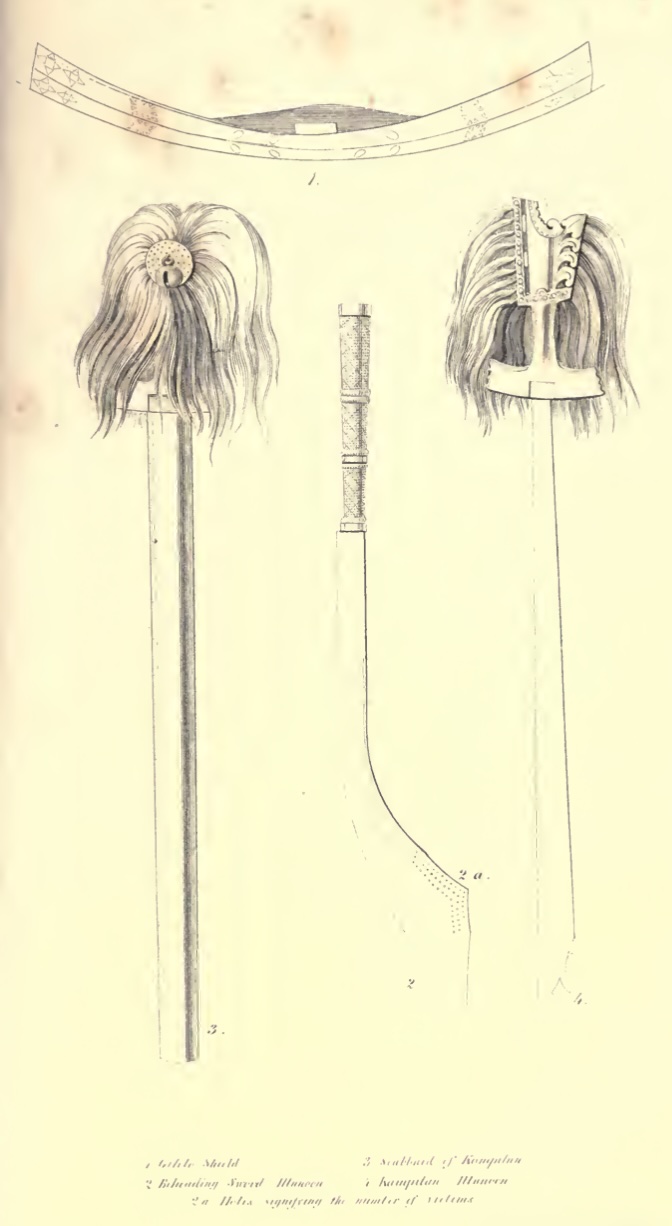

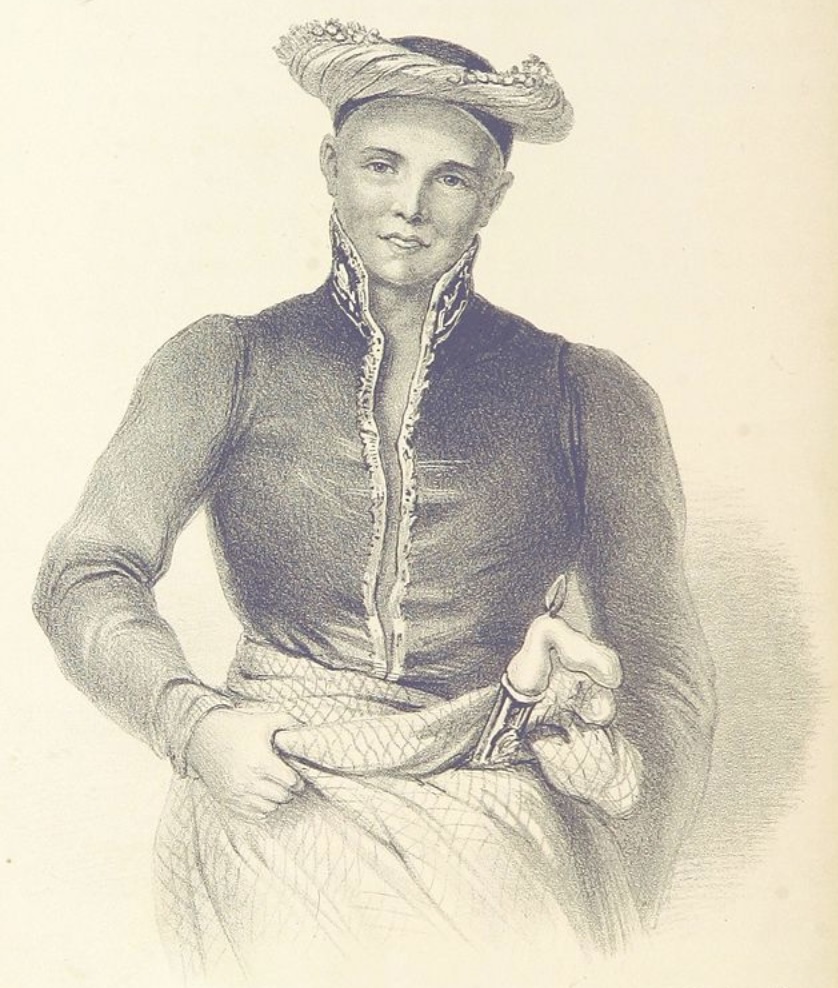

Above the cabin is the fighting deck, upon which their heroes are placed, and upon any chance of action, they dress themselves in scarlet, and are equipped very much in the style of the armour furnished for the stage property of our theatres, varying from steel plate to ring chain, or mail shirt. Their personal arms are generally the kris or the spear, but they also have a huge sword, well known as the “Lanoon sword”, which has a handle sufficiently large to be wielded with two hands … [3]

Nor was the pirates’ organisation any less formidable. On the fringes of the bay that served as their home base, they built into the mangroves ramps made of timber, which they used to haul their vessels into the lagoon and out of harm’s way, on the approach of the enemy. So adept were they at effecting their escape that, even if the prahus were being hotly pursued, and everything was in plain view, invariably they still got away. For, no matter how quickly the chasing launches reached the point of entry, the Illanuns’ prahus had already disappeared and, in their stead, the pursuers found themselves confronted by heavy guns firing volleys of round and grape.

It is a well-known fact, also, that the whole line of the bay is rigidly watched by vigias, or small look-out houses, built in lofty trees, and immediately on the alarm being given, ropes are instantly led to the point of entry, and the home population in readyness to aid in hauling them through the mangroves, as well as to defend them from further attack …

… The slaves who have escaped from these pirates assert, that within the Lagoon they have extensive building establishments, and the means of repelling any attack that may be made upon them. The old prahus are used instead of houses, and in them they have their wives, families, or treasure, in readiness for removal to any part of the lagoon, upon any sudden emergency. [4]

Belcher, who visited Hong Kong in 1841, detected similarities between the Illanuns and the Tanka boat people whom he encountered there, for the pirates lived in “an isolated and distinct community, subject alone to the rule of their Admirals”. At their direction, he says, they collected for special expeditions and then proceeded to sea “in divisions”. On occasion, these could comprise as many as four hundred sail:

The limit of their cruizes are not confined to the neighbourhood of the Sooloo or Mindoro Archipelago, they have been traced entirely around the islands of New Guinea, on the east; throughout the straits, and continuous to Java and its southern side; along the coast of Sumatra, and as far up the Bay of Bengal as Rangoon; throughout the Malay Peninsula and islands adjacent, and along the entire range of the Philippines.

Belcher regarded the Balanini as a subset of the Illanuns. The island after which they were named (today’s Balanguingui) is in the eastern side of the Sulu Archipelago, and it afforded them as much protection as the lagoon protected the pirates of Mindanao:

It is not approachable within distance of attack, by reason of the reefs which environ it, and there is not anchorage near the edge of the reef. It is a Lagoon Island, and the entrance is so narrow that it is staked precisely similar to the ways alluded to at Illanon, only admitting one vessel at a time, and that by preserving her keel exactly in the centre; consequently the Spanish faluas cannot enter, and if they did, they would be met by batteries within, mounting above one hundred guns, all laid with great precision to this very point of entrance.

Beyond this home base, however, the Balanini’s centre of operations extended, in the west, from Basilan Island, south of Zamboanga, to Banguey Island (next to Balambangan) and Tempasuk in Sabah and, in the east, from Maludu Bay right around the coast of Borneo as far as Banjarmasin. They also frequently followed the Illanuns to the Malay peninsula and Singapore.

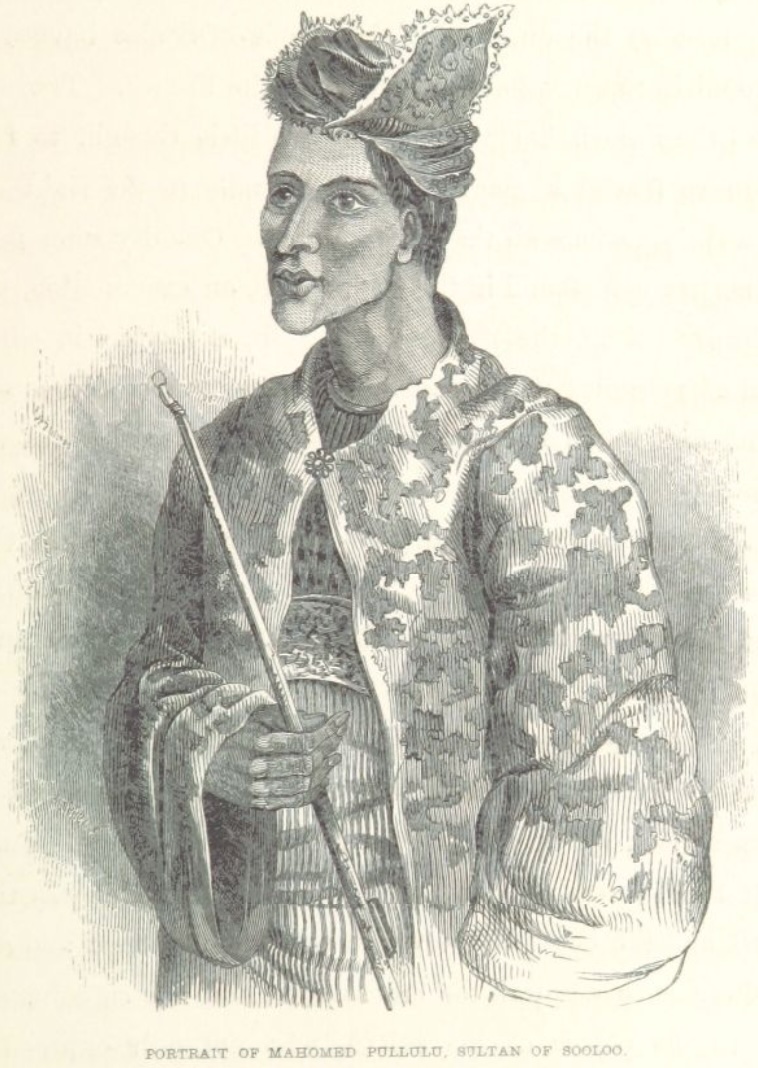

In 1815, a Briton, J. Hunt, lived for six months in the Sulu Islands, after which he prepared a detailed report for Stamford Raffles. In it, he contrasted the sultan of his day with the rulers of the other Malay states, arguing that, whereas they were despots, “he is a mere cypher, neither feared or respected; his orders disputed by the meanest individual, unable to decide on the most trivial points”. The sultan and his chiefs, Hunt declared, seldom rose before ten or twelve o’clock, and frequently later, to give the fumes of opium time to “evaporate from their aching heads”. They went about in perpetual fear of assassination. In sum, he asserted that, “though perpetually boasting of their courage and prowess, they are known to be, the most dastardly race in the universe”; and they were in thrall to the pirates. [5]

Hunt catalogued twelve establishments on the islands (including one at Tantoli, on Celebes). These, he said, were infested some with 8,400 pirates, who had at their disposal a fleet of at least 150 prahus. He was convinced that they were intimately connected with the Sulu government, “sharing their spoils, disposing of their booty, refitting and obtaining their supplies from the Sulo Datus”:

The share of the Booty reverting to the Sultan and Ruma Bechara is twenty-five per cent of all captures. They must respect the Sulo flag and pass and commit no depredations on vessels actually at an anchor at Soog roadsted. The Datus advance guns and powder, for which they are to be paid a stipulated number of slaves.

Sulo is not only the great Commercial mart of all the surrounding ports on Magindanao and the Celebes, but the capital of a great portion of Borneo and all the contiguous islands. It is the nucleus of all the piratical hordes in these seas, the heart’s blood that nourishes the whole and sets in motion its most distant members.

… The depredations committed by these pirates during the six months we remained at Sulo, (as far as come to our knowledge) were as follows; viz. One Spanish brig from Manilla, laden with sundries; twenty smaller craft, captured among the Philippines; One thousand slaves kidnapped from the Spanish islands and sold at Sulo; One large Paddiwakan from Macasser with sundries; The Dutch Commander ransomed by Capt. Peters of the Pinang brig Thainstone, for twelve hundred Spanish Dollars. Five or six smaller craft under English colors captured among the Moluccas. The boats crew of a brig under English colors (name unknown supposed to belong to M Lackerstien of Bengal), consisting of one European and six lascars were seized twelve miles of[f] Sulo town as they were filling water and the whole of them murdered …

According to Captain Rodney Mundy, the Balanini’s prahus were slightly smaller and a little less heavily armed than the Illanuns’, but they had refined a method of attack by which they concealed companies of ten to fifteen men in smaller sampans which they towed behind them. When the time came, these parties separated themselves off, sidled up to unsuspecting vessels, and hooked their crews overboard for a life of slavery using long poles tipped with barbed iron.

And so, it was not hard to conceive of the havoc that the Balanini caused to the pursuit of trade. Mundy summarised the situation as follows:

These pirates have a saying, “That it is difficult to catch fish, but easy to catch a Bornean;” and, on the contrary, the Borneans from being harassed by the pirates, call the easterly wind during the SW monsoon, “The pirate’s wind”. [6]

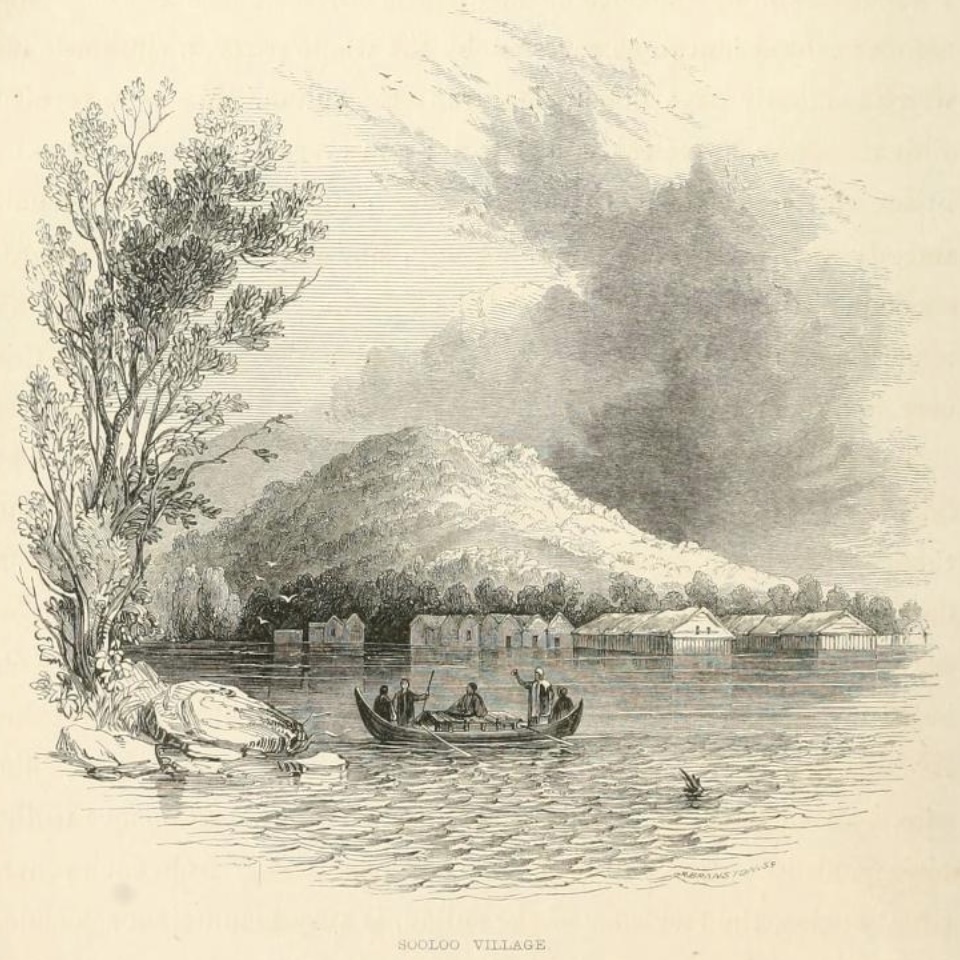

To return to the Examiner: The writer of the article which caused Spenser St. John such offence was responding to another which had appeared in the Edinburgh Review the previous July. It had remarked that, in one rather surprising respect, the Archipelago’s pirates were far removed from “the homeless highwaymen of Hounslow Heath”. Typically, they lived in sweet villages of graceful houses, located in picturesque valleys, and surrounded by gardens as “trim and well-ordered as any in China”. The paper also observed that, instead of a people united in their religion, or perhaps even defined by it, the inhabitants of these villages were an eclectic mix of the devout and the heathen, the civilised and the savage. It was not uncommon to enter one house exhibiting,

… proofs of the civilisation of Western Asia characterised by the fierce fanaticism of the Arabian Peninsula, while next door, perhaps, you perceive long strings of human heads depending in festoons, or gathered up in nets ready to be exhibited in the orgies of some Pagan festival.

Was it therefore not surprising that, once a year, at the right season, there emerged from among these disparate occupiers of a tropical paradise, “a ruthless band of buccaneers”?

Indeed it was, responded the Examiner:

For infidelity, here is a sketch which equals Pinto’s account of the treasures of Mastaban (Martaban). It is wonderful that it did not occur to the writer that he was huddling together the attributes of two different states of society which could not coexist. A taste for neat and graceful houses and trim well-ordered gardens after the Chinese fashion would quickly abolish piracy, while rampant piracy would prevent the taste from springing up. In all the populous and more civilised parts of the Archipelago, piracy has long ago been swept away by honest industry. The Koran in one house, and a festoon of pickled heads at the next door, is just as incompatible an association as buccaneering and Chinese gardens. The alleged Mahomedan fanaticism, every one knows, would not submit to the abomination of the neighbourhood of the pickled heads for an hour.

One gets a sense here of an argument that is becoming detached from reality. For what it is worth, Spenser St. John’s retort was that the Examiner “might with equal justice have asserted that Louis XIV would not love war and fine buildings, or that the Duke of Wellington, the warrior of the age, was incapable of enjoying the luxuries of Apsly House, or appreciating the beauties of his park at Strathfieldsay”. St. John’s real quarrel, however, was with the Examiner’s contention that “the pirates have never captured a vessel however small, with a European crew … or even with a considerable part of the crew European”, and that for them to capture even a regular Chinese junk would be an “achievement above the might of the combined fleet”. This, he said, was complete nonsense:

In the Possessions Neerlandaises by Mon. Temminck, it is stated (vol ii p.233) that the pirate prahus of Billiton (Belitung) in 1821 amounted to 200. In 1822 (p.233) the Royal frigate Melampus, and five vessels of the Colonial Marine with 1,000 auxiliary native troops, in an expedition captured 50 pirate prahus. In 1823 on the same authority, it is stated that a certain Raja Djilolo – venant même exercer ses violences jusque sous le feu du fort Victoria à Amboine – this Raja was attacked and eighty of his prahus captured. In the Moniteur des Indes vol ii p.20, it is stated that on 28th June 1839, on the Eastern Coast of Sumatra, the Dutch troops were attacked by 200 pirate prahus …

… The assertion of Sir Samford Raffles that even Dutch cruizers had been captured previous to 1811 is fully confirmed by Temminck, and the capture at a subsequent period of four Dutch cruizers is recorded by that gentleman. Yet, the public is led to believe that piracy in the Eastern Seas is a mere nuisance and not formidable. [7]

To cite an incident closer to the time of this writing, St. John also directs his readers to an article in the Singapore Free Press of 1847, which referred to forty to sixty prahus issuing from Balinini, ravaging a great portion of the Archipelago, sweeping the Straits of Banca, burning a village not far from Singapore, carrying off a portion of the inhabitants into captivity and exchanging shots with a Dutch fortress on the Borneo coast. Eleven of these prahus, he adds, were attacked by the Company’s steamship Nemesis, and the largest of them was an estimated eighty feet in length, manned by a crew of eighty, and mounted an iron nine- or ten-pounder, and six to eight smaller guns.

Should it be a surprise, he asks, that someone as knowledgeable as Sir Stamford Raffles had concluded that, in number, the pirates “cannot in any way be estimated at less than 10,000 fighting men?” [8]

Capt. Belcher Engages the Pirates at Jilolo, June 1844

Such then was the state of affairs when, on 3 June 1844, Captain Edward Belcher pounded with crowbars the coral of an island off Jilolo, in order to set his instruments and establish his position. (Jilolo, now Halmahera, is the largest of the islands of the Moluccas). When the morning observations had been taken, he heard a shout from the bushes and descried a group of forty natives, each dressed in scarlet and carrying a bundle of spears. They advanced “in a hostile manner, capering and yelling” and, if this and the spears did not give them away, the colour of their clothes, so different from the dull attire of the peaceful traders of those parts, certainly did.

Belcher ordered the instruments loaded upon his gig, and a warning volley fired over the heads of the advancing warriors. As the fusillade put them to flight, a large prahu came into view. It attempted to cut off Belcher’s protecting barge, but then caught sight of the six-pounder in her bow and sheered off. At this point, rather surprisingly, a man stood up and, waving a Dutch flag, shouted out to Belcher, in English, that he “belonged to Tidore”, and was seeking to get away from the island himself. For a short while, Belcher was taken in. He gave the man leave to proceed, only to observe him change course as soon as his prahu was out of range. A warning shot and a Congreve rocket followed in his tail, but a disappointed Belcher confessed that “this only accelerated his motions, and he effected his purpose”.

At this juncture, the phlegmatic Belcher, who did not wish to lose his observations, waited for his afternoon sights. Once these had been taken, he packed up his instruments and made for the rear of the island “with a view to retaliate this piece of treachery”. Two more prahus were seen leaving the shore. As the gig gave chase, a party burned the village from which they had come “in the usual style”, and six more prahus, “evidently designed for piratical pursuits”, were destroyed. Those that were earlier seen escaping were overhauled, and their crews received a dose of round shot and grape as they scrambled away over the reef. Their prahus were towed out to sea and burned. Belcher and his men then reconnected with the gig and, since it appeared unsafe to remain in the neighbourhood, they moved to a secluded bay some twenty miles distant.

That evening, after the awnings on their vessels had been spread, and all but the watch had retired to rest, the sound of gongs was heard across the water. There was barely time to clear for action before five very large prahus came into view. Each was about ninety feet in length, with high stem and stern posts, prettily decorated with long curled ribands of bleached palmetto. They were on the hunt for prey and, when they spotted the British craft in the gloom, they reckoned them a comfortable prize. Belcher writes,

As we, in our barge and gig, had five of these huge vessels to contend with, decision was important, and from their extreme length we had the decided advantage, of rapidly turning, and of preventing their getting us directly a-head; had they accomplished this, they would have been able at one effort of their oars to run over and overwhelm us. It also enabled us to avoid their bow-gun, which they had some difficulty in turning out of the direct line a-head.

The British in the barge opened fire with their six-pounder and, with this, they picked off three of the prahus with round shot and canister. The remainder made off, pursued by the gig. Their crews reached a nearby bay and were severely handled by musketry as they fled into the jungle.

Yet all was not over for, the following dawn, Belcher spotted that the gig had been cut off by another division of five even larger prahus which, unseen, had taken up a position in line abreast and “were evidently bent on more decided resistance”.

Determined to rescue the gig from the grip of the enemy, Belcher immediately advanced in the barge, firing shot, canister and rockets. Soon, two of the prahus were seen to be listing heavily, as their crews scrambled overboard. Belcher continues,

The prahu that had occupied the van continued firing, and I was just aiming a rocket at the Chief, who was waving his kris aloft in defiance, when a well-directed shot from his brass gun struck my rocket-frame from beneath, and glancing upon my thigh, knocked me overboard, wounding me severely. Fortunately, I had sufficient presence of mind to hold on by the gunwale of the boat and thus supported myself until assisted into her …

Five others were now advancing, and one came within musket shot, but on examining the state of our ammunition it was reported that all the percussion caps were expended, and that but one round shot for the six-pounder remained. The rocket-frame was also knocked overboard with me.

As the enemy appeared to thicken from different quarters, and as all the advantage on our side would cease with the discharge of the six-pounder, I was obliged to give up the idea of taking out our prizes …

One large prahu appeared inclined to try her luck with us, but I was not displeased to observe her change her course and join those we had left, as I considered the fresh force which would follow up this matter upon my reaching the ship, would like to have their share of the amusement.

When the Samarang had been regained, the engagement entered its final phase. A party in the barge and two of the ship’s cutters was sent to find the gig, which had not yet been recovered. They all then returned to the scene of the previous day’s exploits, where they saw twelve to fourteen prahus moored within a creek behind a village, protected by the low tide, which had laid bare a reef:

The boats immediately opened fire upon the prahus, which they endeavoured to destroy, at least sixty round shot, beside Congreve Rockets having entered them. This was not effected without opposition; their fire was instantly responded to from a masked entrenched battery, in which was one heavy gun, apparently iron, and several smaller of brass, the latter no doubt withdrawn from their prahus for defence. Finding nothing further could be done, they pulled round the Peninsula, where they suspected a communication to be open in the rear of the village; here they found two small prahus, evidently despatch boats, which they towed to sea and burned.

The party then returned to the Samarang, which made sail for the Strait of Patientia between the islands of Bacan and Halmahera. There, they fell in with a schooner under Dutch colours. Her master came aboard and was quizzed about the pirates of the neighbourhood. From the description he was given, he agreed with Belcher that those he had encountered must have been Illanuns, as “no vessel so large, or so equipped for war, belonged to any of the petty authorities of the neighbouring states.” Probably, it was thought, they were the remainder of an Illanun fleet which had recently been bested by a Dutch squadron off the east of Java, and were returning to their base. [9]

This was not, however, the opinion of all for, when he reached Singapore, another group of Dutch officers accused Belcher of having attacked ships and crews actually employed by them to suppress piracy. A formal protest was lodged with the British authorities.

Belcher did not, in the enquiry, mention the spears of the first party of natives: was it not likely, therefore, that they had innocently come to enquire who the British were, and were not hostile, as Belcher supposed? What exactly did the first prahu do to deserve having a Congreve rocket fired at it? In fact, did it not hoist a Dutch flag? And what was the justification for setting fire to the Jilolo village? Frank Marryat, no great admirer of Belcher, volunteered the suggestion that “the authorities at Singapore appeared to think we were to blame”, before he detailed the Dutch arguments. “That their observations were true”, he wrote, “it must be admitted, and the complaint of the Dutch, with the hoisting of the Dutch flag, gave weight to them.”

In the event, however, the Admiralty Court judged the statutory award of bounties should be paid, as “very meritorious service had been performed”, there having been “not less than 1,350 persons on board the several prahus at the beginning of the attack, 350 of whom were killed.” (Marryat thought this a significant over-estimate). In the admirals’ opinion, it was unfortunate, but the Dutch had made the mistake of employing pirates to deal with pirates.

Spenser St. John says he later met at Sulu a man who took part in the action, who told him,

The Sultan of Jilolo sent a fleet of boats to take prisoner a tributary rajah of New Guinea, whom they got on board and killed. In returning, they saw the Samarang’s boats, which the chief man took for native prahus, though our informant insisted they were Dutch boats, upon which the order was given to fire, and they were astonished by the severe thrashing they got from our blue jackets, under the command of Sir Edward Belcher.

St. John’s opinion, therefore, is that the pirates were from Jilolo, not Illanuns, even if their red attire suggested otherwise. Whatever the merits of the case, the crew of the Samarang were awarded “head money” of about £10,000 and their captain a pension of £250 a year. [10]

At the Court of the Sultan of Brunei, October 1844

This incident sparked the beginning of a concerted effort by the British to deal with the sea pirate menace. As a result of the involvement of James Brooke, it ultimately led to regime change in Brunei and to the establishment of a British outpost on Labuan – a process we will now explore.

Brooke at this time was engaged with Captain Henry Keppel in his famous campaign against the river pirates of Borneo (a troublesome breed certainly, if not quite the equal, in terms of the peril they posed, of the Illanuns and Balanini). Belcher and Keppel met in Singapore shortly after the Jilolo incident and when, in July 1844, Keppel prepared to depart for Sarawak in HMS Dido, with the steamer Phlegethon, he invited Belcher to join him. Belcher was still injured, however, so he missed the expedition’s famous assault on the Patusan fort; he wrote that he later “had the satisfaction of examining the still smoking ruins of the stockades, which they had so gallantly stormed and carried.” [11]

Thence, Keppel was ordered back to England and, in his place, Belcher accompanied Brooke to Brunei. With them, packed into the Sultan’s barge, “in a space not sufficient for half their number”, went the family of the Rajah Muda Hassim, the uncle of Brunei’s sultan. Belcher wrote,

Any description of the fuss and ceremony of their embarkation would be tedious. As one important feature, it was imperative no inferior eye should behold these fair creatures, and to obviate any such profanation, the awnings were spread, the after part of the vessel screened off with heavy canvas, and the people kept in the fore part of the vessel. Late at night, the Royal barge came alongside by torch-light, and each precious individual, carefully concealed by a mantle, was smuggled singly into the vessel and carried below.

… [On arrival at Brunei] I found matters in a state far from pleasant. A boat had been despatched from the Phlegethon … to acquaint the Sultan of the arrival of his uncle the Rajah Muda Hassim and to request the immediate assistance of the state barges to take out the ladies, one of whom had actually died of exhaustion in the confined air below; all had suffered severely and the Rajah himself was covered with a fine rash, similar to miliary, as well as those children which they now ventured to expose to the air. Although at the moment of their greatest exhaustion, it had been urged upon the Rajah to shield the women from notice by screens on deck, still he would not consent to their removal to purer air … [12]

Hassim, James Brooke’s sponsor in Sarawak, was opposed in Brunei by his cousin, Pangeran Usop, the illegitimate son of Sultan Mohammed Tuzudin, over whom Hassim had been given precedence in the succession. (It should be recalled that Brunei was then the titular controller of all of what is now Sarawak and Sabah.) Marryat explains that factionalism aroused by the jealous Usop had earlier induced Hassim to retire to Sarawak with his half-brother Bedrudin, and to resign the throne in favour of his nephew Omar Ali Suffedin, “a man of about sixty years of age … said to be very imbecile, and under the control of his ministers.” [13]

Now, Marryat says, Hassim decided he should return to Brunei to refute the charge, levelled against him by Usop, of being in league with the British. As stated, the accusation was not unreasonable, but Hassim had his view of where Brunei’s best interests lay and, at his back, Brooke was objecting that Brunei was doing nothing to suppress the pirates; even that it was actively recycling their plunder.

To his countrymen, Brooke was declaring that, as soon as the menace had been extirpated, Borneo would be restored to a state of comparative civilisation. Yet, Belcher’s explanation of his motives is surely as close to the truth. For Brooke was not disinterested in shoring up the base of his support among the Dyaks, the native peoples of Sarawak:

Mr Brooke seemed to be strongly impressed with the expediency of removing the Rajah Muda Hassim, with his thirteen brothers, to Borneo Proper (Brunei). They were considered as at present a dead clog on the advancement of the Dyak interests; and although the Rajah Muda, and one or two of his brothers, might feel disposed to further the views of Mr Brooke respecting them, still there existed that latent feeling, on the part of the Malay, to consider the Dyak subservient to his purposes, and to oppress him by petty and troublesome inflictions. So long as this existed, [and] Malay Pangerans, relatives of the Sultan of Brunai, remained at Kuching, the Dyak tribes would continue to doubt the power of Mr Brooke to control them. [14]

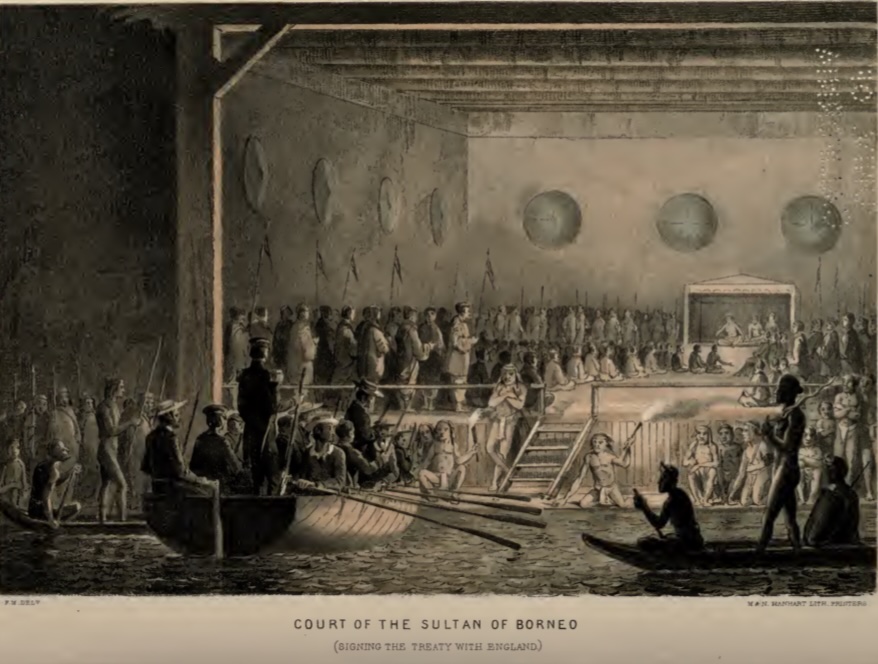

When, in October 1844, it became known in Brunei that Hassim was returning in the company of a British delegation led by Brooke, there was consternation. Belcher says that the government was warned to expect a force of sixteen or seventeen vessels, and that Usop prepared the battery at Pulo Cherimon, in the Brunei River, for the defence of the capital. When an advance party, consisting of Bedrudin and Brooke’s interpreter, Thomas Williamson, approached it in one of the Phlegethon’s boats, they were told, in terms that were considered “offensive” and “insulting to the British flag”, to keep off. Belcher, who was following behind, wrote, “Fortunately, [the insult] did not occur to our boat, or instant punishment would necessarily have ensued; nor was the extent of the insult ever communicated to me”. [15]

This sets the tone for the famous meeting at which, almost in the shadow of the guns of the steamer’s boats and of Belcher’s barge, the Sultan signed the treaty by which he bound himself to respect the British flag, to make over the island of Labuan, to destroy the fort on Pulo Cherimon, to discountenance piracy, and to install Hassim and Bedrudin into offices becoming their rank. According to Marryat,

Seraib Yuseef, who was inimical to the English, expressed his disapprobation of their demands in very strong terms: as for the sultan, he had very little to say. As it appeared there was no chance of our demands being complied with without coercion, the conference was broken up by our principals pointing to the steamer, which lay within pistol-shot of the palace, and reminding the sultan and the ministers that a few broadsides would destroy the town … Our situation was rather critical, only eight Europeans among hundreds of armed natives taking their sultan in this manner by the beard, when, at a signal from him, we might have all been despatched in a moment. More than one chief had his hand upon his kris as we stalked through a passage left for us out of the audience chamber; but whatever may have been their wishes, they did not venture without authority.

On reaching the platform outside, a very strange sight presented itself. With the exception of a lane left for our passage to the boat, the whole space was covered with naked savages. These were the Maruts, a tribe of Dyaks who live in the mountains. The word marut signifies brave. These naked men, who are very partial to the sultan, had come down from the mountains to render assistance in case of hostility on our part. They were splendidly framed men, but very plain in person, with long matted hair hanging over their shoulders. They were armed with long knives and shields, which they brandished in a very warlike manner, occasionally giving a loud yell. They certainly appeared very anxious to begin work; and I fully expected we should have had to draw and defend ourselves. I was not sorry, therefore, when I found myself once more in the stern sheets of the barge, with our brass six-pounder loaded with grape pointed towards them.

Their purpose obtained, the British returned to the Samarang, sailed for Labuan and anchored in the harbour, which Belcher renamed Port Victoria in honour of his Queen. Yet, two years were to pass, and much blood was to be spilt, before the Union Jack was hoisted on Labuan Island and, by then, Hassim had been murdered. [16]

The Downfall of Brunei’s Pangeran Usop

The first step in the process was the destruction of Pangeran Usop who, in the course of his quarrel with Hassim, had allied himself with Serip Usman, the holder of an extensive fiefdom at Maludu Bay, at the northernmost end of Borneo.

In the Sulu treaties of the 1760s, Alexander Dalrymple described Maludu as one of “the Sooloo dominions on Borneo”, and John Herbert’s associate Thomas Forrest tells us that it was included in the territory granted by the Sulus to the East India Company. At the time, the sultans of Brunei might have protested their right to make the grant but, by now, the weakening of the Sulus in their wars with the Spanish, and civil strife in Brunei meant Maludu had become largely independent of both.

Moreover, Usman had married a daughter of the Sulu sultan and had entered into alliances with the Balanini and with the Illanuns at Tempasuk. Supported by their protection, the stability which Usman brought to his powerbase attracted a significant community of Cochin Chinese traders, as George Windsor Earl observed during his visit in the early 1830s:

The north-east end of Borneo has not, I believe, been visited by a British vessel since the abandonment of Balambangan, but, according to the accounts of the Bugis traders who sometimes touch there, a very interesting change has lately taken place. They assert, that large bodies of Cochin Chinese are now established on the shores of Malludo Bay and the adjacent parts; and as the Cochin Chinese are known to be settled in considerable numbers on the neighbouring island of Palawan, there appears to be no reason for doubting the correctness of the information. This part of the coast is so situated with respect to the monsoons, that voyages to and from Cochin China may be made with the greatest facility at all times of the year; and in addition to this favourable circumstance, the number of navigable rivers and well-sheltered harbours, the fertility of the soil, and the absence of all likelihood of opposition on the part of the Dyaks, would render the spot better adapted for Cochin Chinese colonization than any other in the Indian Archipelago. [17]

Indeed, before he had established himself in Sarawak, James Brooke’s attention had been drawn to Maludu by Earl, as well as by the reports of Stamford Raffles and Alexander Dalrymple. As early as 1838, before he departed London in his yacht, Royalist, he published a prospectus on a Proposed Exploring Expedition to the Asiatic Archipelago. In it, he declared Maludu to be the spot he had chosen “for his first essay … [as] the mere fact of its being a British possession gives it a prior claim to attention”. Its position relative to China was advantageous. More fancifully, he thought that “in all probability a direct intercourse may be held with the Dyaks of the interior”, and that its location at the western end of the archipelago (sic) neatly balanced that of the recently established Australian settlement at Port Essington. In sum, he wrote that, “The servants of the company attached to their settlement of Balambangan were decided in opinion, that this bay was far preferable in every respect, to the station chosen and subsequently abandoned”. [18]

That Maludu was free from the influence of either the Spanish, or the Dutch, increased its interest. That it was beyond the reach of Hassim was unfortunate. However, its connection with the Illanuns and Balanini gave Brooke the opportunity he required to involve the British Navy in its suppression, and thereby to shore up his support at Brunei.

When he arrived there, in March 1845, he was handed a letter in which Hassim “begged” him,

… to take measures to protect Borneo from the pirates of Marudu, under Sheriff Housman, who is, as we all know, in league with some of the Pangerans of Borneo, ill-disposed to our government, in consequence of our agreement with the English, and the measures we have taken to suppress piracy.

Two months later, Brooke wrote to his friend John Templer, complaining of the British government’s failure to follow through on their promises:

I am sorry to tell you, that affairs in Brunei are by no means progressing so well as I could have wished, and that it is to be attributed to our total inability for want of power, and orders to act. It is now two years since ____ received from them their first agreement, and since then, they have been fed upon promises, whilst we have come and returned with one story, “wait, wait”. Under these circumstances, it is not then to be wondered at, that the bad faction, headed by Pangeran Usop, are making head, and our good friends dropping for want of support, and suspecting our will or our ability to assist them. Muda Hassim and Budrudeen are threatened from without by Sheriff Osman, the pirate chief, because they have declared for the suppression of piracy. Within Pangeran Usop conspires against their power – the sultan is doubtful – and the mass of the people on both sides lukewarm and confused. The position in which they are now placed is entirely our doing, and if the sacrifice be complete, or the town convulsed by civil war, it can only be attributed to our slowness and inaction.

Finally, during a visit to Singapore in the same month, Brooke made his case to Sir Thomas Cochrane, Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies and China Station, and received a promise of his support. [19]

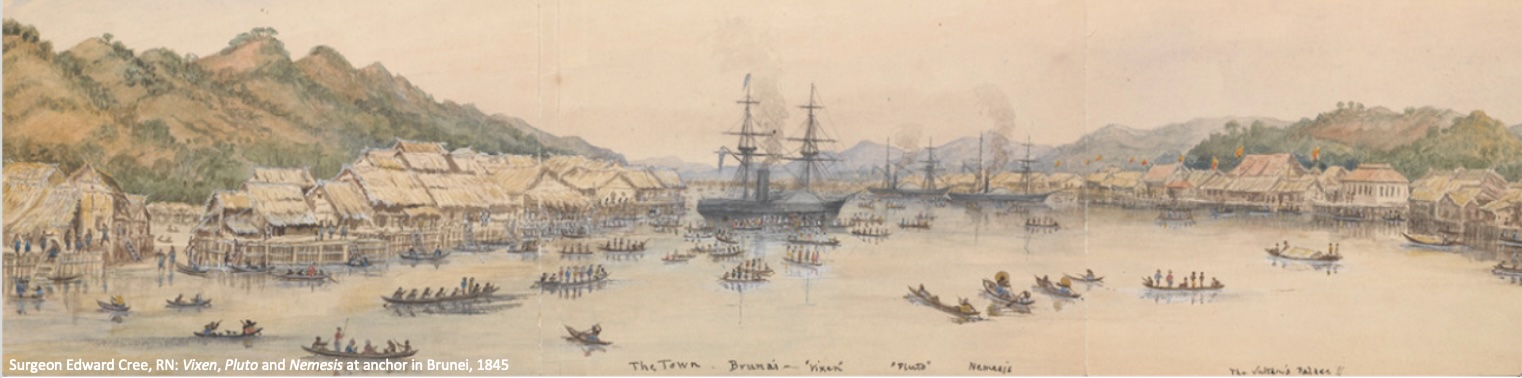

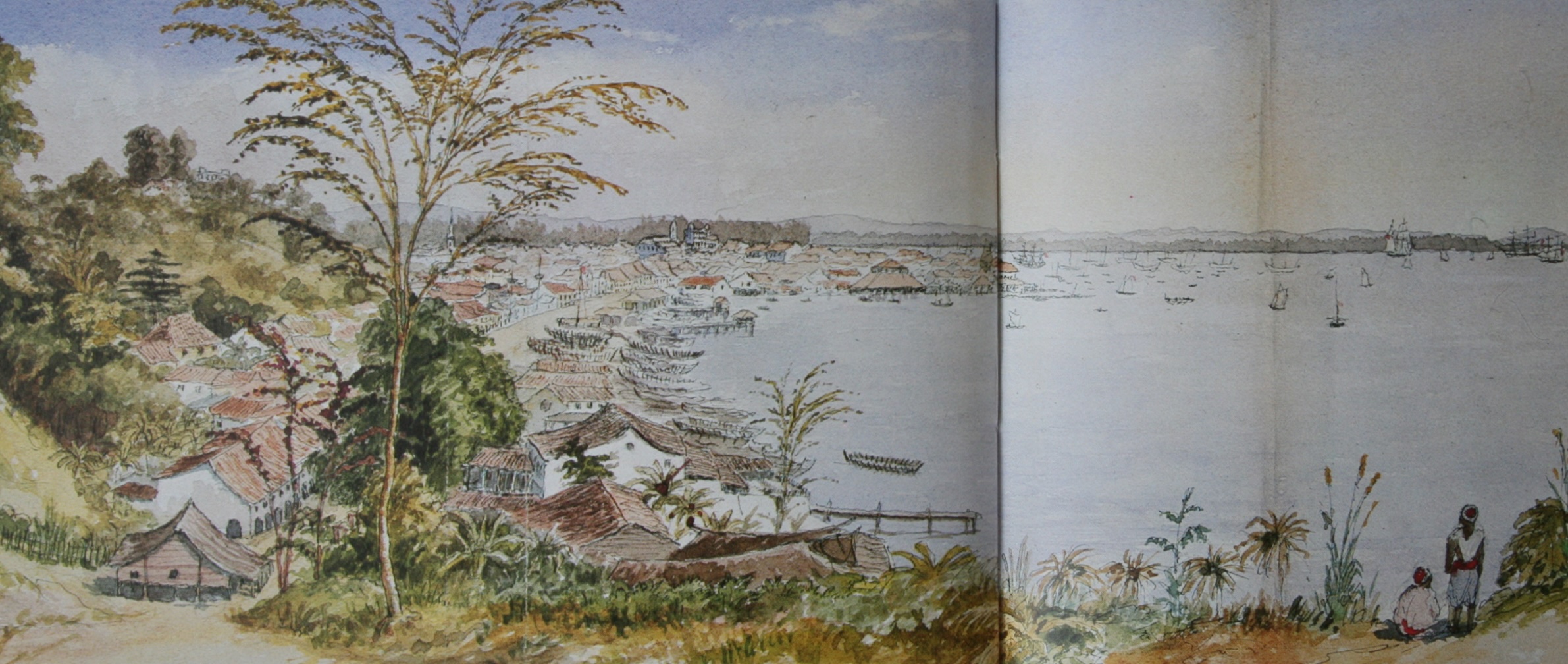

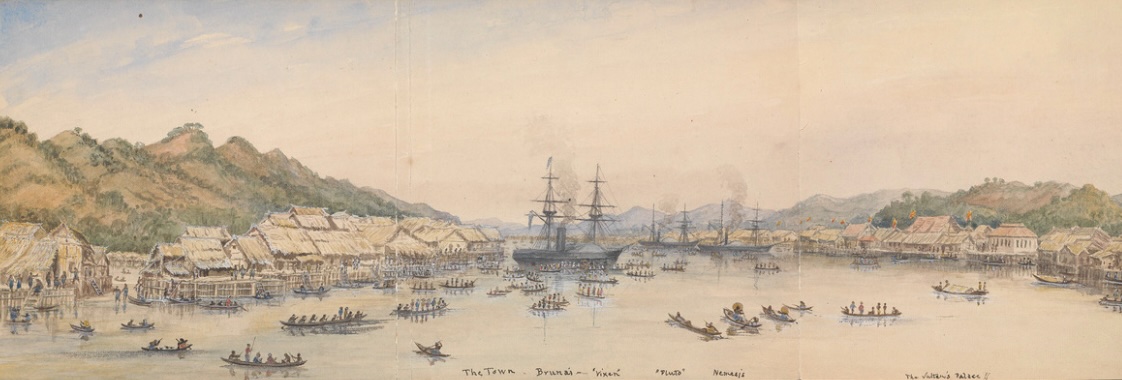

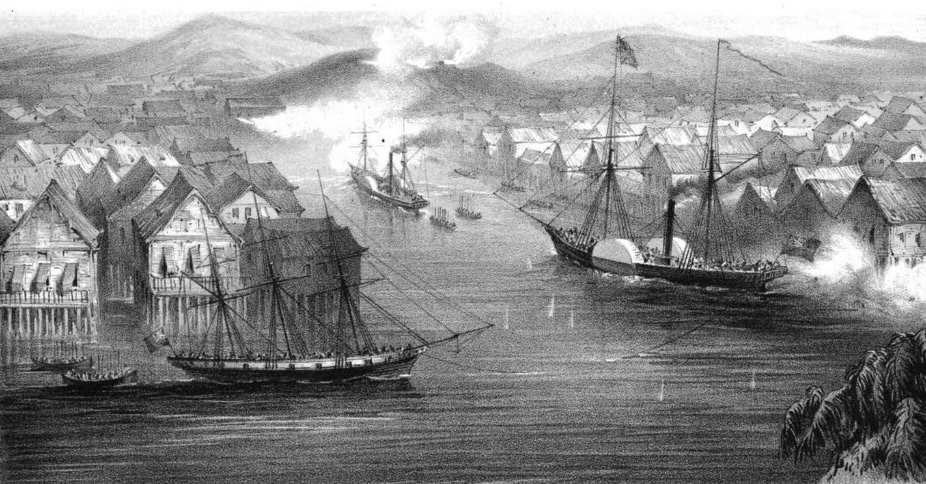

On 8 August 1845, a squadron of eight vessels, including the steamers Vixen, Pluto and Nemesis, anchored at the entrance of the Brunei River. Aboard the Vixen, the Surgeon Edward Cree described the scene:

A sudden bend of the river brought us in sight of the town, an extraordinary looking place built on piles, extending a couple of miles along sandbanks on each side of the river, generally nearly dry at low water. The houses are mean, built of wood, thatched with palm leaves. The population, about 10,000, almost live in their narrow, light canoes. We anchored about 6 o’clock in the centre of town, in 6 fathoms of water, the Pluto and Nemesis half a mile further up the river. [20]

Captain Rodney Mundy, commanding HMS Iris, confided more solemn thoughts to his diary:

It is not easy with such a force to be moderate and, with Sir Thomas Cochrane’s other duties and engagements, it is probably impossible for him to devote any time to this coast: yet moderation and time are the keystone of our policy; and if Malludu be destroyed, and a brig left to support our friends, and to drive Usop away should he attempt to return, we could afford to be moderate, and not to spill blood. I feel myself very reluctant to accede to any propositions which aim at Usop’s death, and I will try to save him in the coming events, unless I be thoroughly satisfied that his living endangers the life of Budrudeen. [21]

During the day, the Vixen was surrounded by canoes bearing ducks and durians, which were exchanged for empty bottles. At the same time, some well-dressed Malays came aboard, who Cree judged were “probably spies.” Later, the canoes departed and, ashore, there was a great commotion, as the inhabitants moved away their furniture and their children. The sentries were doubled, and all went on the alert.

At about eleven o’clock, a request was received from Brooke, who was with the Sultan, to send a party of Marines, as he had been warned that Usop was planning an attack. All then went quiet until two o’clock, when Cree was awoken by a fearful shriek:

I heard someone cry out, “They are boarding us over the starboard bow” … My half-awake thoughts were that a desperate attack had been made on us by the Malays: I seized my sword, but it having been such a peaceable weapon, it refused to leave the scabbard, being rusted in. The other officers were also rushing on deck where there was the wildest confusion, men tumbling over one another in the dark, the drummer beating to quarters, men rushing about with their drawn cutlasses, searching for the enemy, who were nowhere to be seen. We then found out it was a false alarm. On enquiry, it was discovered that one of the midshipmen happened to be sleeping on the deck, next to a young officer of Marines. The night being hot, they were not much encumbered with clothes. The middie was restless, and in his sleep put his cold arm across the young Marine’s throat, who dreamt that a Malay was cutting his throat, and screamed out lustily; hence the commotion and panic. [22]

On 9 August, Cochrane, accompanied by Hassim, Bedrudin and Usop, went to the Sultan and told him he had come “to offer him every assistance to suppress his piratical enemies without, and to punish any turbulent men who in Brunei troubled his government.” Mundy wrote,

The sultan was much obliged, looked pallid, and trembled. Then came the crash of the band, the rattling of the marines’ arms; the rise, the embrace, the descent, and the return to Pluto. What touched my heart at the close of the audience was pangeran Usop seizing my hand from behind. Poor devil, I pity him; but measures must advance, and he has deserved his fate, whatever it may be. [23]

His fate soon became apparent. Cochrane demanded reparation for the seizure of two British subjects from the Sultana, a merchant vessel which had foundered after being struck by lightning off the coast of Palawan. The Sultan’s reply was evasive and timid. He said that Usop had been responsible and that he had not been able to restrain him; Cochrane should do as he saw fit.

Usop had no intention of giving in without a fight. He barricaded himself inside his house where, as Hassim reported it to Brooke, he was seen loading his guns and preparing for a night attack. The following morning, he was ordered to appear before the Sultan, but chose to remain where he was. By two o’clock in the afternoon, Cochrane had run out of patience. Brooke wrote to his friend John Templer,

The steamers then were moved into position, the marines landed, ready for advance, and some twenty minutes grace afforded him. This over, the first shot was fired over his house from the Vixen, which was instantly returned by two or three shot at us. Up went the signal, commence action, – the iron shower was hurled upon the devoted house, and before the third shot I believe no living soul was in the house, all having, with becoming prudence, Pangeron Usop at their head, sought safety in flight. [24]

When the firing ceased, Edward Cree was sent ashore in his role as surgeon. He found about a dozen bodies of unfortunate Malays and just one sailor, who had fainted from the heat. In addition, he discovered that one of the Vixen’s 10-inch shells had pitched close to Usop’s magazine and, fortunately, had not exploded:

The Rajah had removed most of his valuables and his women, but a quantity of goods were found, an English calico, a sextant, chronometer and telescope. A pair of cut glass decanters and a quantity of English crockery was found, but given over to the natives, as looting was strictly forbidden … We took away twenty-two guns of small calibre, mostly Spanish or native manufacture, two of which the Admiral kept; the remainder were given to the Sultan. A new suit of English boat-sails, charts &c., were probably the proceeds of plunder of some unfortunate merchant vessel wrecked on the coast. A Captain and Mrs. Page had been wrecked some time ago, and made prisoners by this very chief, and afterwards ransomed for 12,000 dollars. We found a couple of natives of Bengal who had been made prisoners and slaves. We sent them aboard the Pluto among their own countrymen, to their great delight. We also found a Japanese, who had been seventeen years in slavery among them, but he refused to leave.

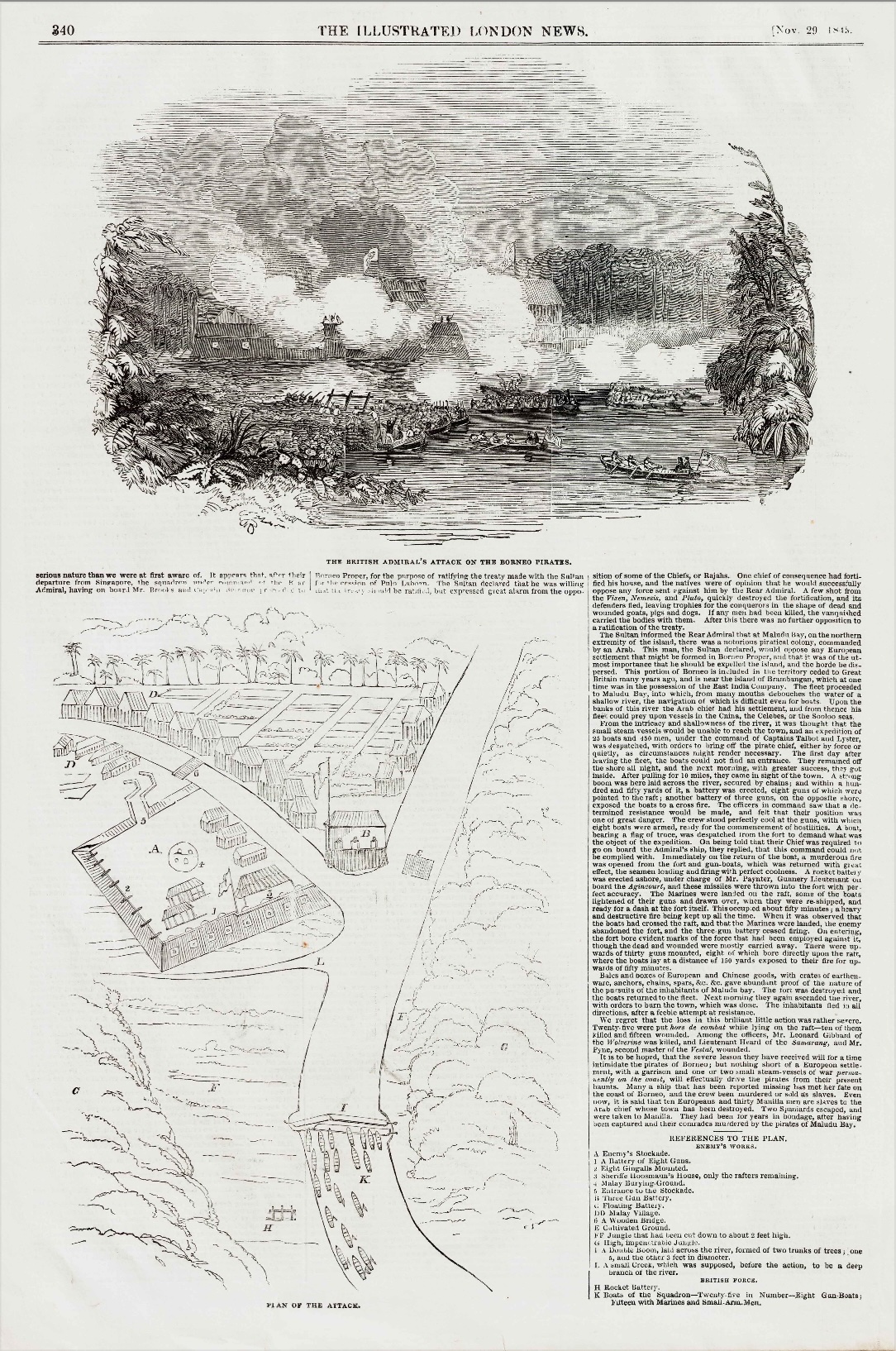

The Illustrated London News for 29 November 1845 reported that Vixen’s first warning shot, “fired with a view to the intimidation of the pirates” actually passed through the roof of Usop’s house rather than over it. His shots, it added, passed over the Vixen, “falling harmlessly into the buildings on the opposite side of the river, which had been long previously evacuated by the panic-stricken inhabitants.” Cree agrees with the ILN, adding that Usman’s returning fire “was most ridiculous, as a broadside from our 84s and 32s sent his stockades and other defences flying in splinters”.

On the following day, Cree returned to take another look at the fragments of Usop’s house. Nothing of value remained; the natives were even carrying off the banana trees and betel palms from his garden. The stench from the dead was already “very offensive”. There were many wounded being cared for by the natives whom, Cree says, “he was obliged to leave.” He comforted himself with the thought that they led healthier lives than the British and, as a result, recovered more quickly from their injuries. He then adds,

The poor Sultan was in a great state of alarm during the firing; his harem revolted, and some of the ladies escaped by swimming across the river. An officer and a guard of Marines had been sent to protect the Sultan, but the ladies were disposed to monopolise all the Joeys’ protection on themselves, the red coats were so attractive. [25]

Thinking Usop had been dealt with, Sir Thomas now sailed for Maludu. In this, he was a little precipitate. Two days later, Usop returned to Brunei with two hundred men and launched an attack on the city from a fortified hill behind his demolished house. He was driven off by Bedrudin and sought the protection of the chief of nearby Kimanis, who owed him allegiance:

The Orang Kaya protested his loyalty, but, a few days after, receiving an order from the Government to seize and put his guest to death, he made up his mind to execute it. He imparted the secret to three of his relations, whom he instructed to assist him. Pangeran Usop was a dangerous man with whom to meddle, as he was accompanied by a devoted brother, who kept watch over him as he slept or bathed, and who received the same kind offices when he desired to rest. For days the Orang Kaya watched an opportunity – tending on his liege lord, holding his clothes while he bathed, bringing his food, but never able to surprise him, as he or his brother were always watching with a drawn kris in his hand. The three relations sat continually on the mats near, in the most respectful attitude … On the tenth day Pangeran Usup, while standing on the wharf, watching his brother bathe, called for a light. The Orang Kaya brought a large piece of firewood with very little burning charcoal in it, and the noble in vain endeavoured to light his cigar. At last, in his impatience, he put down his kris, and took the wood in his own hand. A fatal mistake! The treacherous friend immediately threw his arms around the Pangeran, and three watchers, springing up, soon secured the unarmed brother. Usup was immediately taken to the back of the house, and executed and buried on the hill.

The mode of execution for state offences was simple and dignified. A thick mosquito net was given to the prisoner, in which he wrapped himself. He seated himself on the ground and gave the signal. A cord was placed around his neck, and he was strangled. [26]

The Battle of Maludu Bay, August 1845

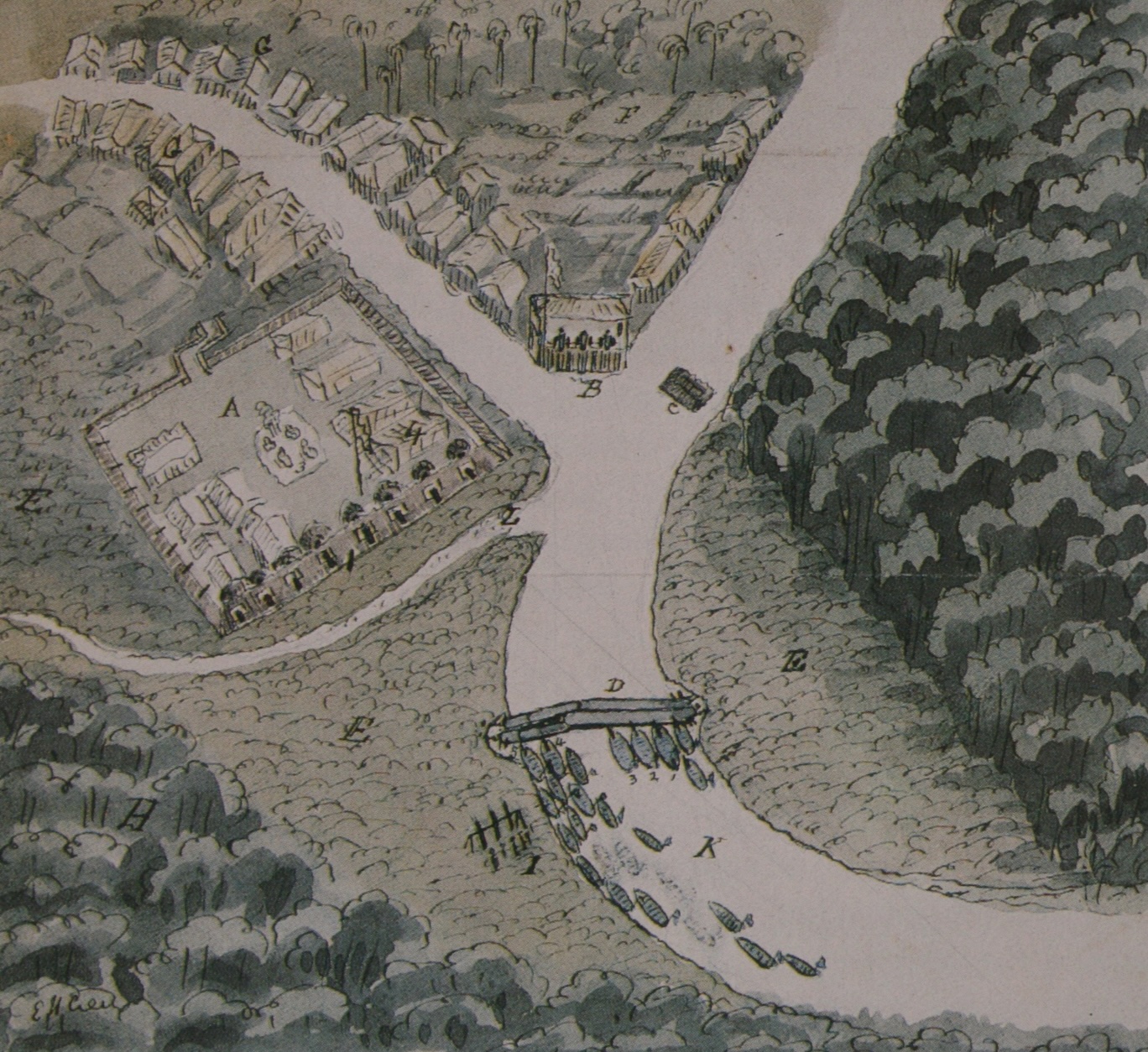

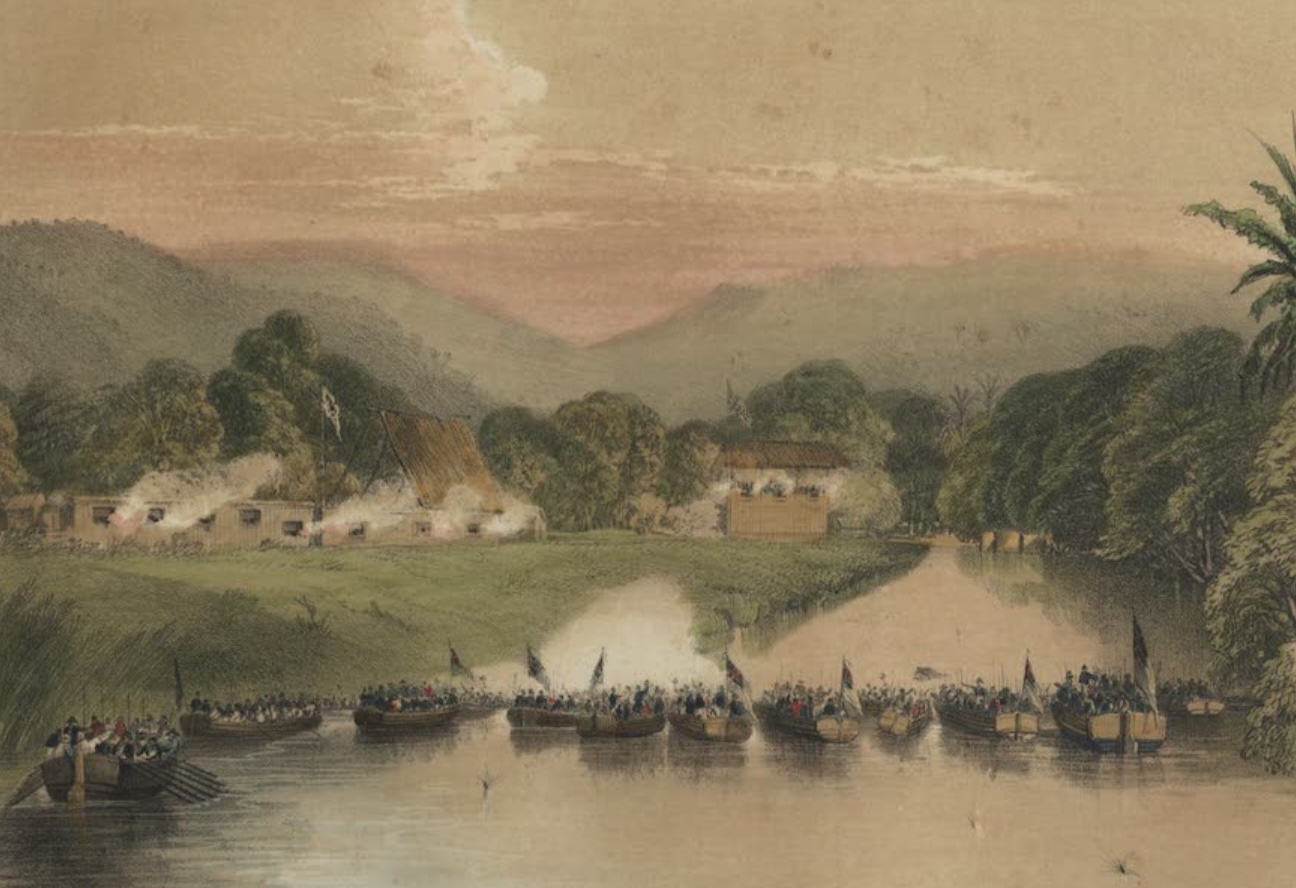

Sir Thomas Cochrane’s squadron entered Maludu Bay on 17 August. The following morning, Vixen, Nemesis, Pluto and boats proceeded up the bay and anchored as close to the entrance of the Maludu River as possible. Serip Usman’s stronghold was a few miles upstream, behind a sharp bend in its course and so hidden from view. On a spit of land formed between the principal stream and a tributary he had built a fort defended by a battery of three guns. There was another, larger, fort on the right bank with eight guns, and a floating battery on the left, opposite it.

In front of all, some 150 yards downstream, was a double boom of tree trunks bolted together with iron plates and bound around by an iron ship’s cable (“European”, the ILN pointedly remarked). This was secured with iron clamps to the trees on each riverbank. No boat of any size could pass through it, or over it, and on it were trained the guns of the forts.

On 19 August, Captain Talbot of the Vestal was sent with the boats of the squadron to reconnoitre. The boom certainly posed a challenge, but the middle fort could only be assaulted from the river, and it appeared that the larger fort, over which Usman’s banner – a red flag with a tiger’s head – was visible, was defended by another stream on its right. In fact, this proved to be just a shallow creek, over which, in the course of the battle, some parties from the rear were to cross quite successfully. Talbot, however, decided there was no alternative but to attempt to cut a way through the boom. In support of his assault, a rocket battery was erected downstream of the fort on the river’s right bank.

At this juncture, a flag of truce was brought to the boom by a chief in a canoe. Cree says the message was unsatisfactory, “as they only asked for delay”. Talbot demanded Usman’s unconditional surrender and then prudently declined an offer to return to the main fort, with two officers, to negotiate. The chief hauled down his white flag, and battle commenced:

The three-gun battery immediately opened fire on the boats which had been driven up to the boom by the strong flood-tide. Our fellows soon returned their fire with interest. The firing was hot and sharp, both from the great guns and musketry. In the meantime every effort was made to cut away the boom, but this proved most formidable work under a heavy fire from the forts.

…The first few discharges from the enemy’s guns told with deadly effect on our gunboats, knocking over many of our poor fellows. The enemy’s guns had been so accurately laid for the dreadful boom, against which the boats were forced by the tide, that their shot ploughed along through the press, but the quick firing from our boats soon made the enemy’s aim less certain, and as our shot told with more effect, their aim became less steady, and now and then, when a rocket took good effect, or a shot told well, a rallying cheer from our fellows showed that as the game became hotter the enemy’s courage cooled. After a party of our men had been working desperately for fifty minutes at the boom, an opening was made near the right bank of the river, and through it rushed the boats with a true British cheer, which completely terrified the enemy from their guns. They were now seen escaping through the embrasures and over the parapets in crowds, and only one or two guns continued to fire, and these were soon silenced. The small-arm men and Marines soon rushed to the front and finished the business. Only the dead and the flying were to be seen.

According to the report in the ILN, on the British side there were ten killed and eleven wounded (Cree says six killed and fifteen wounded, two of them mortally). In the circumstances, Cochrane judged it “rather astonishing” the casualties were not more numerous.

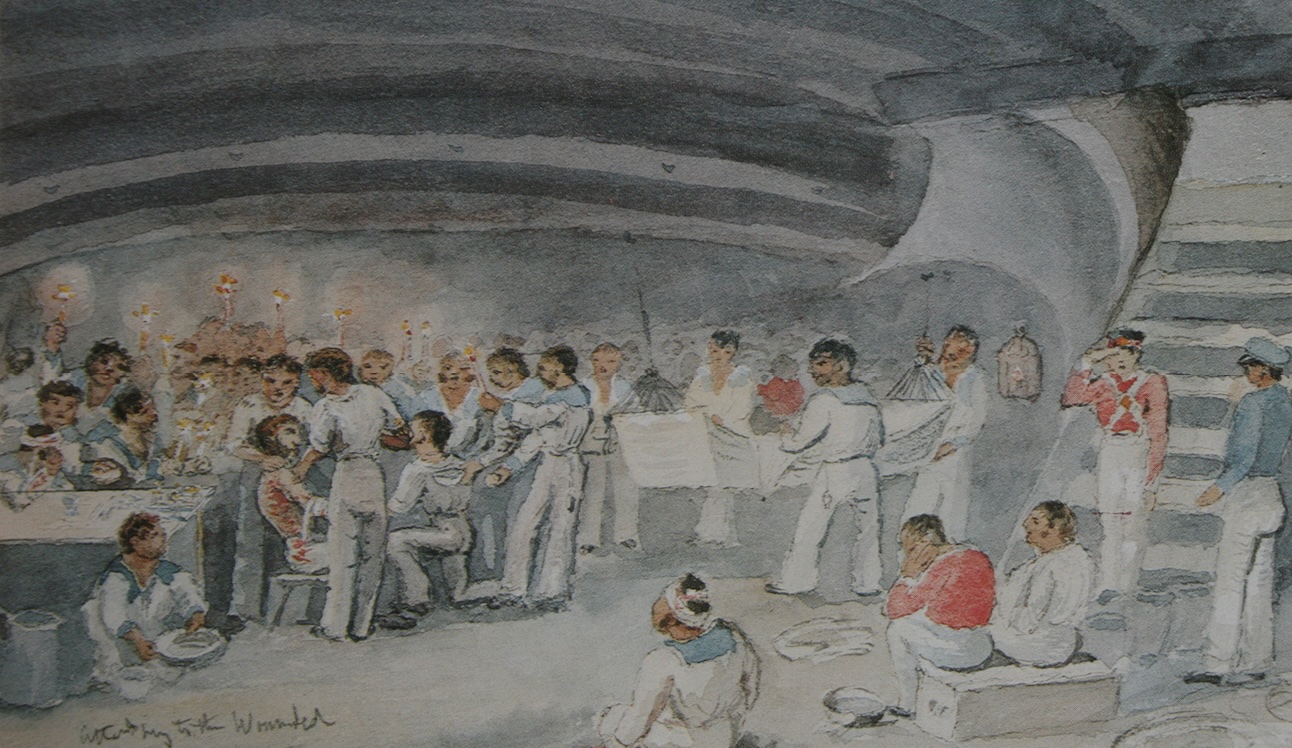

The wounded were taken aboard the Vixen, where surgeon Cree tended to them. He writes:

One poor fellow, Joshua Darlington, AB, had his right arm terribly shattered by a large ball, which had entered at the back of the deltoid muscle, smashing the head of the humerus and traversing the whole of the arm, lodging in front of the wrist. Nothing could be done to save the arm, so that I at once proceeded to remove the limb at the shoulder joint … Surgical operations on a crowded deck, by the light of half a dozen dip candles, with too many excited lookers on, are not done under the most favourable conditions, but one had no choice, and my patient made a good recovery. He received his wound when in the act of loading his musket.

According to the ILN, estimating the number of the enemy’s casualties was made difficult because the pirates’ slave-prisoners were ordered either to pitch the dead into the river as they fell, or to carry them away into the jungle. This was because it was considered a great disgrace for them to fall into the hands of the enemy. Nevertheless, the paper suggested the losses must have been “immense”, as its reporter came across two prisoners who said they had been kept busy committing corpses to the river for upwards of five hours. Osman himself was thought to have been dangerously wounded and to have died later in the jungle.

On 20 August, a detachment of ten boats, accompanied by Brooke, completed the work of destruction begun the day before. Keppel reports,

Numerous proofs of the piracies of this Seriff came to light. The boom was ingeniously fastened with the chain cable of a vessel of 300 or 400 tons; other chains were found in the town; a ship’s long-boat; two ship’s bells, one ornamented with grapes and vine leaves, and marked “Wilhelm Ludwig, Bremen;” and every other description of ship’s furniture. Some half-piratical boats, Illanun and Balagnini were burned; twenty-four or twenty-five brass guns captured; the iron guns, likewise stated to have been got out of a ship, were spiked or otherwise destroyed. Thus has Malluda ceased to exist; and Seriff Houseman’s power received a fall from which it will never recover.

To the ILN, the equipment found in the fort “gave abundant proof of the nature of the pursuits of the inhabitants of Maludu Bay”. Whilst expressing the hope that the severe lesson they had received would intimidate the pirates for a time, it argued that “nothing short of a European settlement, with a garrison and one or two steam vessels of war permanently on the coast, will effectually drive the pirates from their present haunts”. It continued,

Many a ship that has been reported missing has met her fate on the coast of Borneo, and the crew been murdered or sold as slaves. Even now it is said that ten Europeans and thirty Manilla men are slaves to the Arab chief whose town has been destroyed. Two Spaniards escaped and were taken to Manilla. They had been for years in bondage, after having been captured and their comrades murdered by the pirates of Maludu Bay.

In fact, in respect of the Wilhelm Ludwig, Belcher was told by the Spanish governor of the Philippines that she had been wrecked on the reefs east of Banguey, in 1844, and that Usman had done no more than go there to recover salvage left behind by the crew. [27]

The Capture of Brunei (1846) and the British Colony on Labuan

Immediately after these events, the British fleet anchored on the north-eastern side of Balambangan. There Cochrane left the Vixen and returned to his flagship, Cree writing “no one in the Vixen is sorry, as he is at times disagreeable about dress, and very pompous. He is himself a regular old buck, and looks as if he kept himself in a bandbox.”

Of Balambangan, Brooke wrote in his diary, on 22 August,

Examined the NE harbor; a dreary-looking place, sandy and mangrovy, and the harbour itself filled with coral patches; here the remains of our former settlement were found: it is a melancholy and ineligible spot. The SW harbour is very narrow and cramped, with no fitting site for a town, on account of the rugged and unequal nature of the ground; and if the town were crammed in between two eminences, it would be deprived of all free circulation of air. Water is, I hear, in sufficient quantity, and good. On the whole, I am wretchedly disappointed with this island; it has one, and only one recommendation, viz., that it is well situated in the Straits for trading and political purposes; in every other requisite it is inferior to Labuan. [28]

However, if Brooke thought the sack of Maludu would cement Hassim’s position at Brunei and ensure that Labuan was confirmed under British ownership, he was to be disappointed. For a daughter of Usop, who had married an adopted son of the Sultan, soon persuaded her father-in-law that he should rid himself of her husband’s pro-British uncles.

Hassim perished first. Attacked in his home by forty or fifty armed men, he retreated across the river, where he defended himself and his family for some time before bundling them into a boat, filling it with gunpowder and firing the train. He survived the explosion, but ended by blowing out his brains with his pistol.

His brother Bedrudin’s house came under attack at the same time. Bedrudin fought bravely, but his companions were cut down one by one and he was wounded in the wrist, shoulder and chest. Resigning himself to the inevitable, he withdrew to a room at the rear and blew it, and himself, his sister and another young lady to smithereens. In total, thirteen of the Sultan’s uncles, nephews and cousins perished that night. [29]

Brooke was distraught, and he demanded revenge, but Brunei was an independent country, and its sovereignty had to be respected. It was not until the summer of 1846 that a squadron comprising the ships Agincourt, Iris, Ringdove, Royalist and Hazard, and the steamers Spiteful and Phlegethon entered the Brunei River. When the batteries on Cherimon Island opened fire, they provided the justification needed for determined action. On 8 July, Plegethon carried the river forts and led the Spiteful and Royalist to the heart of the city. The Sultan, his army and the inhabitants had fled, and so, as Captain Mundy puts it, “as the moon rose over the desolate buildings, she showed the white tents of the marines encamped on the heights in strong relief against the dark jungle beyond.”

Mopping-up operations followed against the Sultan’s allies and against the Illanun pirates at Tempasuk, on the Pandassan River, and at Ambong. Ambong, a thriving town when Sir Edward Belcher visited it shortly before, had been looted and burned to the ground by the Ilanuns, but from the Phlegethon there was no escape. Eventually, it was agreed that the Sultan should remain in post, provided that he appointed ministers friendly to Europeans, supported lawful trade, discouraged piracy and observed the treaties to which he was party. On 18 December 1846, the treaty ceding Labuan to Britain was signed. [30]

Unfortunately, like Balambangan, Labuan proved largely to be an ill-judged fantasy.

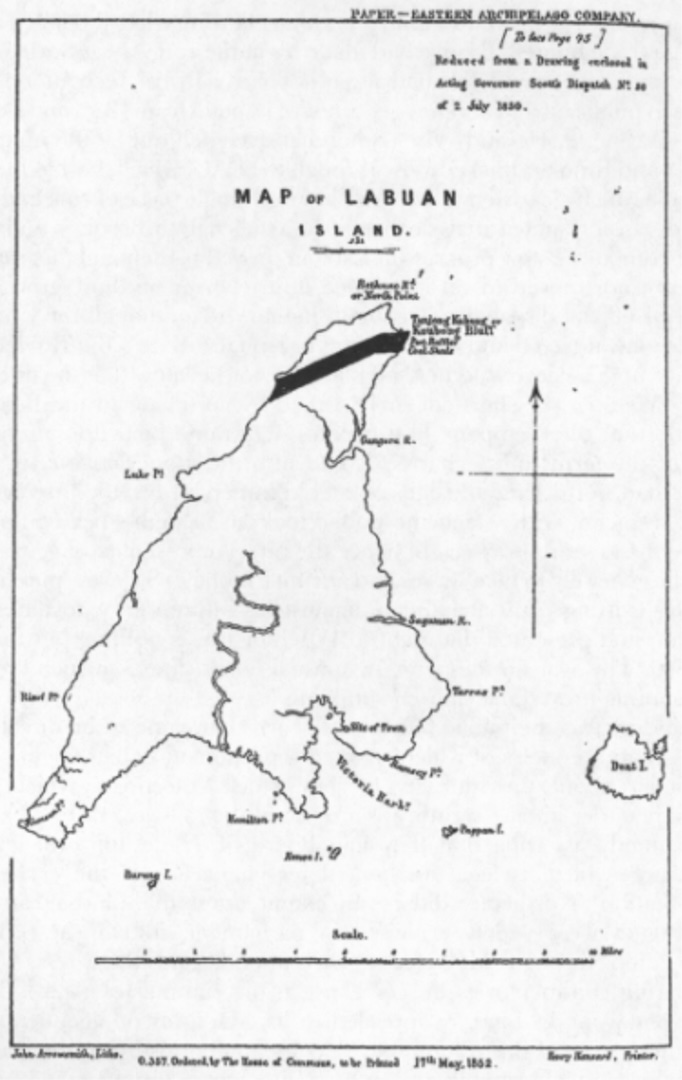

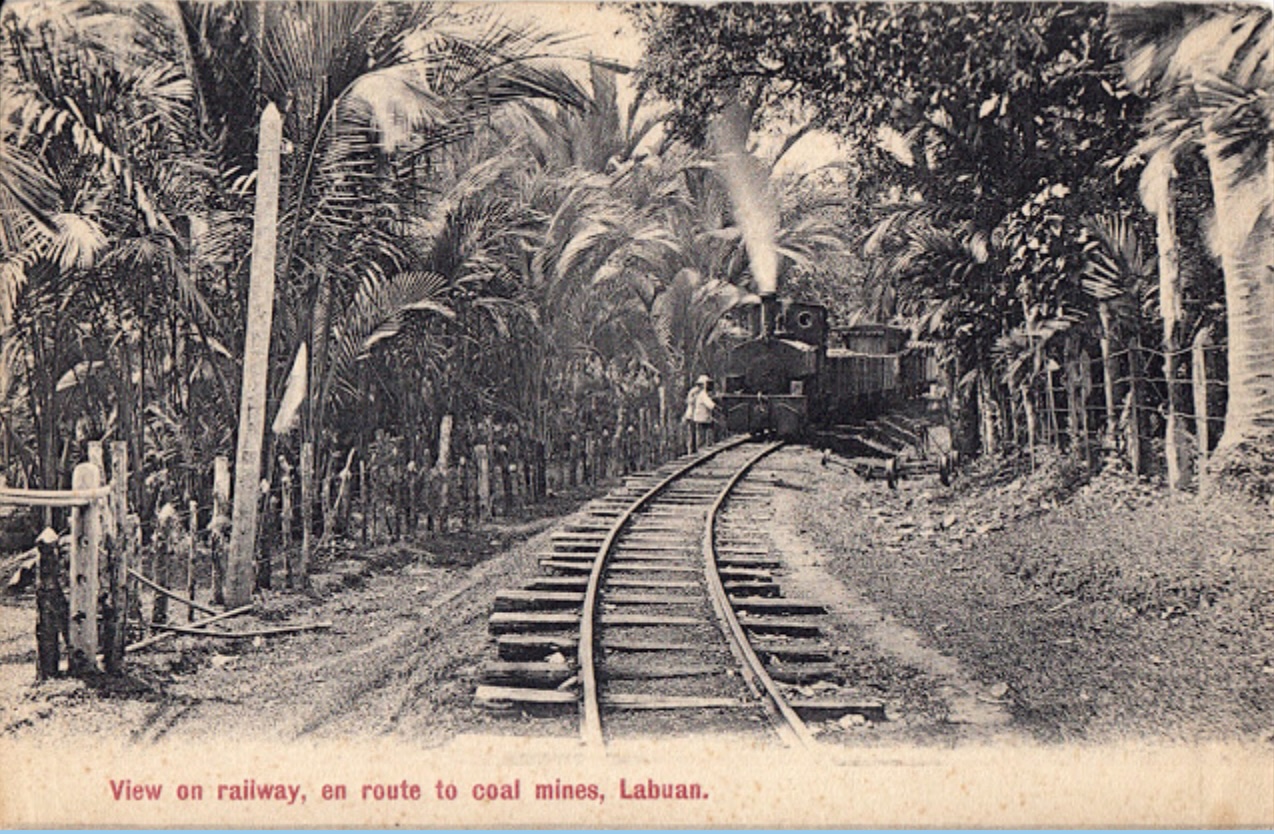

“As a windward post relative to China”, Brooke admitted, Balambangan was superior, as “it commands in time of war the inner passage to Manilla, and the eastern passages to China by the Straits of Makassar.” Against it, Labuan offered advantages in every other respect, “a better port; a better island; a better soil … close to friendly Brunei”. Its smaller size meant it would be cheaper to secure. But its greatest strength was its reserve of coal which, in the new age of steam, made it potentially an important station for the Navy. [31]

As John Crawfurd, who had earlier been British Resident at Singapore, put it,

Between the eastern extremity of the Straits of Malacca and Hong Kong, a distance of 1,700 miles, there is no British harbour, and no safe accessible port of refuge; Hong Kong is, indeed, the only spot within the wide limits of the Chinese Sea for such a purpose, although our legitimate commercial intercourse with it extends over a length of 2,000 miles. Everywhere else, Manilla and the newly opened ports of China excepted, our crippled vessels or our merchantmen pursued by the enemy’s cruisers, are met by the exclusion or extortion of semibarbarous nations, or [are] in danger of falling into the power of robbers or savages.

Labuan fortified, and supposing the Borneon coal to be as productive and valuable in quality as it is represented, would give Great Britain in a naval war the entire command of the China Sea. This would be the result of our possessing or commanding the only available supply of coal, that of Bengal and Australia excepted, to be found in the wide limits which extend east of the continents of Europe and America. [32]

It was with this in mind that Belcher had been sent to Labuan in 1844. He found coal at one or two of its north-eastern extremities and they promised more. The seams were between eight and ten inches thick and they inclined towards the main body of the island, suggesting there were further resources to the southward. Specimens of coal from just across the strait in Brunei had previously been forwarded to the Lords Commissioner of the Admiralty and had been found to be “of a quality quite equal to our best Newcastle.” Yet Belcher wrote,

I am still of opinion that coal could at all times be landed direct from England at less than the cost of raising it, either here or at Brunei, independent of the almost insurmountable difficulty of obtaining labourers: and I am perfectly satisfied that it would prove advantageous to load vessels, intended for any settlement formed here, with coal as ballast, to which may be added the very small tonnage of dry goods, which might be required; and having delivered here, take in timber for Hong-Kong, which could readily be procured either at Labuan or the adjacent land, and would prove a valuable article at that colony. [33]

It was a report made after the most perfunctory of visits; Belcher was running late, and he evidently felt he had more important things to do. Nonetheless, it is a shame Brooke did not heed his advice.

In August 1846, the Sultan of Brunei granted Brooke a right to work coal on Borneo’s mainland, in exchange for $2,000 in the first year and $1,000 annually thereafter. These rights were granted to Brooke personally, but he had no intention of mining the coal himself and so, after he had offered them to the British government, and they had declined them, he transferred them into a private company controlled by his London agent, Henry Wise.

In 1848, Wise moved to corner the coal on Labuan. In January, he personally secured a thirty-year lease on a five-hundred-acre block for a rental of £100, plus a royalty of 2s./6d. per ton, on output in excess of one thousand tons per annum. In July, he sold his rights on both the Labuan and Bornean coal to the Eastern Archipelago Company, of which he became Managing Director. Considering that he had paid next to nothing for these assets, the compensation he received was astonishingly generous: £6,000 within four months of the company’s incorporation, £3,000 a year for ten years, £10,000 worth of shares, £2/10s. in dividends, unless the dividend was less than £7/10s., and an annual salary of £800.

In order to extract the coal, the company targeted an initial capital of £200,000. In March 1848, it announced a share issue, but this was a peculiarly difficult period in which to raise funds. It marked the bursting of a “Railway Mania” and a time when, after a poor harvest, several trading houses failed as a result of speculating on higher corn prices. As a consequence, the project was starved of funds.

A second problem was the growing opposition of James Brooke. From an early date, he was concerned that the royalties to be given to the sultan were much too low; indeed, he wrote to Wise, arguing that the concessions were only ever meant to be permissive, not exclusive, and, when Wise rejected his interpretation of the agreement, he appealed to the Colonial Office. Then, he discovered that, during the commercial crisis, he had lost £10,000 on an investment in Melville & Wise, Henry’s company, for which he judged Wise was to blame. (The precise circumstances are unclear.) At the end of 1848, Brooke broke off all connection with Wise, and they became involved in a vituperative, high profile, dispute.

Wise is best known for his attacks, brought through the newspapers, on Brooke’s campaigns against the river pirates, which he claimed were unwarranted and involved atrocities. Brooke’s most effective criticism of Wise was the charge that, so far from raising £200,000 in capital, the Eastern Archipelago Company had in fact failed to raise even the minimum £51,000 required by its charter.

In the company’s defence, in 1853, the entrepreneur Hugh Hamilton Lindsay, Chairman of the Board, demanded “full, searching, and comprehensive investigations into the proceedings of Sir James Brooke” over the company:

The Company [he wrote] deliberately charge Sir James Brooke with conduct equally discreditable to his character as a public officer and an honest man, in having for a series of years, from motives of private spleen and malevolence, and from direct pecuniary interests of his own, antagonistic to the Company, made a most unscrupulous use of his high position in the service of her Majesty to obstruct and injure the Company by every means in his power, in direct violation of his duty …

In the first balance sheet of the Company, dated, July, 1849, capital stands at £51,455, of which £46,000 is represented as the Property vested in the Company by the Deed of Settlement prepared under the inspection of Mr. Bellenden Kerr, not “a debt of the Company to that amount” as asserted by Sir James Brooke; and £5,455 by payment of 1st call upon 1091 shares.

In fact, this was not the case. Although the company had secured its charter, the coal concession had, as we have seen, been secured by Wise in his own name, and the company had subsequently “purchased” his plant in Labuan against his future salary, royalties and shares – presenting its debt to him in the accounts, as “capital”.

These issues apart, getting the coal out of the ground and aboard ship proved a “beastly” process. As Belcher had forecast, there was an insufficient supply of labour. Borneo Malays were unreliable, and it proved impossible to attract sufficient Chinese. By the end of 1851, the company had shipped only eight thousand tons. Then the recriminations over its accounting sleight of hand came into the open in parliament, the press and the courts. In 1854, the company’s charter was cancelled. [34]

New companies were organised and re-organised, but still the profits failed to flow. To assist them, Brooke ruled that the price of coal should be raised temporarily, but he omitted to tell the Navy. They refused to pay and even made deductions for the cost of transport to their ships, although the contract did not require them.

There were four companies between 1847 and 1880: Eastern Archipelago Company (1847-1858), Labuan Coal Co. (1860-1866), China Steamship and Labuan Coal Co. (1866-1868) and Oriental Coal Co. (1868-1878). Each was guilty of exploiting surface coal deposits and neglecting the deeper veins. At one point convict labour was used with some success, but ultimately this failed because the men would not work underground. The first three companies lost some £100,00 each, the last £150,000. In 1878, the coal works were closed and, in 1885, the Navy abandoned them altogether.

There was some other activity on Labuan, which attracted commerce from the Borneo coast and Sulu, just as the some of the colony’s first promoters had hoped it might. It was supported by a small community of Chinese and Indian traders who handled products such as sago. In 1860, Labuan imports were worth £38,000 and exports £13,000; in 1875, they were £119,000 and £114,000. But with coal output fitful, most traders by-passed Labuan to concentrate on Singapore and, by 1872, there was only one regular commercial service between it and Labuan, operated by Captain John Ross. [35]

The Final Decline of the Balanini Pirates

But this is to look some way into the future. Closer to hand were the events which marked the eclipse of the Balanini. These began, at the end of May 1847, when the steamship Nemesis encountered a force of eleven of prahus on the Brunei River. Brooke was on board, and at his direction, Nemesis gave chase, eventually running the prahus down to the island of Pilungan, where they anchored in line, their bows facing the sea.

Before battle began, the ship’s purser, who volunteered for the role, was sent to parley, but his effort was short-lived, as the Balanini responded to the approach of his boat by opening fire “along the whole extent of their line” on the Nemesis. One sailor was killed, and the purser was retrieved. Then, over a period of seven hours, the Nemesis fired, at a range of two hundred yards, 160 round shot and nearly five hundred charges of grape and canister, while a force of cutters and a body of marines was sent to grapple, hand to hand, with the Balanini on one side of their position. Of the prahus, four were destroyed and one was captured although, owing to the swell, most of the steamer’s shot reportedly “passed into the jungle beyond”. None of the estimated 350 pirates were taken alive, but between fifty and sixty of them were killed, together with a number of their captives, who were chained around the neck and deliberately exposed on deck to the fire of the British. [36]

Six prahus escaped to Labuan where, by chance, they missed the brigs Columbine and Royalist, which were then lying at anchor in Victoria Harbour. They made for the Sulu Sea, but only three lasted the distance, the remainder having been so badly disabled that they foundered off the Borneo coast.

Many of those pirates who made it ashore found their way through the jungle to Brunei. Upon their arrival, the Sultan put arms into the hands of their earlier prisoners and told them he desired them to take vengeance. This they declined to do, and so the Sultan instructed his citizens to carry out the executions in their stead. The pirates were cut down on the spot. [37]

Those Balanini who eventually returned to their home base regrouped and then concentrated their raids in and around the Philippines. In 1848, this brought a final, convincing response from the Spanish government at Manila.

Spenser St. John says that, immediately before this event, the Balanini could muster more than 150 boats of thirty to fifty men – in total, a force of about six thousand. In preparation, therefore, the Philippines Governor-General, Narciso Clavería, equipped his force with three steam vessels ordered from Britain. It helped the Spanish that, at the time of the assault on their base, half the Balanini were away on a slave cruise; nevertheless, the remainder fought ferociously and drove the attackers from their walls three times before the entrance to their fort was forced with artillery. The Spanish were then treated to the sight of the Balanini butchering their own women and children rather than have them fall into the hands of the enemy. The massacre only stopped when the Spanish promised the Balanini clemency; they were then marched off to the ships and a prison on one of the northern islands.

Those who escaped attempted to re-establish themselves in Sulu, but the Sultan there realized that he could no longer defy the Spanish. The Balanini were dispersed by a second Spanish expedition and thereafter turned their attention increasingly to islands, such as Ternate and Tidore, which they had left unscathed for years. Slaving raids occurred in the Philippines also, but the firepower of the Spanish now far exceeded that of the pirates, and the introduction of more steamers forced the Balanini to reduce the size of their flotillas drastically. The British and the Dutch together used similar tactics to protect the coasts of Borneo and, after the bombardment of Tunku by HMS Kestrel in 1878, there was a marked decline in the Balanini raids. [38]

The Bishop of Labuan and Sarawak’s Encounter with the Illanuns

There were frequent incidents involving piracy after this, of course. Captain Jon Dill Ross was one who could attest to that, and so too was Francis McDougall, the first Bishop of Sarawak and Labuan. [39]

In May 1862, the Bishop accompanied the Rajah Mudah, John “Brooke” Brooke, on a cruise to Bintalu on the armed steamer Rainbow. Brooke’s wife, Julia, had just died of fever and it was hoped that the cruise might do something to revive his spirits.

A few days out, it was learned that a fleet of Illanun pirates was blockading Muka. The Rainbow, which was equipped with two nine-pounders, raced to the scene. What followed was described by the Bishop’s wife in a letter to her brother,

… the steamer returned on Sunday morning decked with Illanun flags, which she had taken from a fleet of six pirate vessels. They met them three at a time returning home to their islands, crammed full of captives and booty. They ran over them one by one, sustaining and giving a heavy fire all the time. Frank fought, as you may imagine, till he had his hands full of wounded to dress. There were forty pirate fighting-men in each boat, and from sixty to seventy slaves or captives which they had picked up in a seven months’ cruise. It was a glorious victory, and through God’s mercy none of the eight Englishmen on board were wounded, although many Malays were, and the hospital is full. The pirates are a dreadful people; the tortures that they inflicted on their captives are sickening to write, and the women were all vilely treated. Frank has sent a full account to the “Times”, where I hope you will see it. What a blessing it was that he went; it saved many lives! [40]

According to Ludwig Helms, the principal agent at Sarawak of the Borneo Company, who was also present, the number of Illanuns killed was 190, with thirty-one taken prisoner. Of their captives, 250 were liberated, but many were killed, for the pirates, when they saw they were being worsted, fell upon them and “even young girls were cut to pieces by those to whose brutality they had been subjected.” Among them were people from every part of Borneo, Celebes, Java, Bavian, Singapore, Terrenganu, and elsewhere. In one boat there were one Spanish and six Dutch flags. In appearance, many of the captives “looked mere skeletons; they got sea-water to drink, and unwashed sago for food, while their limbs were systematically beaten to disable them from mutiny or flight.”

The bishop’s letter was written at the request of Brooke and published in The Times on 16 July. It caused the bishop, indeed his archbishop, considerable discomfort. As his biographer explains,

… in his eagerness to enlist the sympathies of his fellow-countrymen, and to persuade the Government to put a stop to a system far worse than the African slave-trade, he forgot to take fully into account the feelings of the religious public at home. In his excess of honesty, he made no concealment of his own action, and committed the extreme imprudence of speaking of the shooting of his rifle, and gave the name of the manufacturer, although he did not actually mention the hand that wielded it.

The Bishop was certainly at the centre of events. He later wrote,

My dress attracted the particular attention of the enemy and the balls fell smartly about my station on the poop. Once I was returning to my post after helping a wounded man on the quarter-deck, and as I was near the top of the ladder, I saw a fellow in the prahu nearest to us take a deliberate aim at me with his rifle; the ball whizzed past my ear and went into poor Hassein’s heart, who was standing behind and above me.

The passage that caused the greatest offence was the following:

I must mention that my double-barrelled Terry’s breech-loader, made by _____, proved itself a most deadly weapon from its true shooting and certainty and rapidity of fire. It never missed fire once in eighty rounds, and was then so little fouled that I believe it would have fired eighty more rounds with like effect without wanting to be cleaned. When we ran down the last pirate all our ammunition for the 9-pounders had been expended, and our own caps and cartridges for the small arms had nearly come to an end, so that if we had had more prahus to deal with, we should have been in a sorry plight and had to trust to our steam and hot water hose to do the work … We are, indeed, almost thankful to our Heavenly Father who thus ordered things for us, and made us His instruments to punish these bloodthirsty foes of the human race.

In the vanguard of McDougall’s critics was the Bishop of Durham who, in October, wrote to the Gospel Propagation Society on what he termed “the extraordinary proceedings of the Bishop of Labuan with regard to his shooting the poor heathen instead of converting them”. He expressed the hope “that some resolution might be adopted, which might free the Society from any share in the blood so thoughtlessly shed.”

In advocating censure, he reminded the Society that,

… a little more than two hundred years ago, when an Archbishop of Canterbury accidentally killed a gamekeeper, he needed to be cleared from the canonical penalty of being suspended from exercising his episcopal functions by a formal commission, although, as Fuller says, “he manifested much remorse and self-affliction for this rather sad and sinful act.”

The Bishop’s biographer was surely correct to suggest this was “a case surely not in point in one single particular, except that in it also was the coincidence of a gun and a bishop.”

The Bishop of Labuan’s friends rallied to his defence, saying that he participated in the fight only until the sinking of the first of the pirate vessels gave a moral assurance of victory. He then betook himself to the care of the wounded. When he embarked on board the Rainbow, they said, it was without the remotest expectation of what followed; that once on board, he could not have left her; that if he had simply taken shelter below, he would have deprived the rest of the assistance that, as an experienced surgeon, he alone was competent to give; “that the conflict was between eight Europeans with fifteen natives, and three prahus, each carrying three long brass swivel cannon, called lelahs, and each containing between forty and fifty fighting men, well-armed with rifles and muskets, and sixty or seventy captives.”

The Bishop himself added,

I grieve indeed heartily at the necessity imposed upon me then, but I am sure that the good Lord, whose providence brought me into such a position, will not lay to my charge any blood that I may have shed. Sure I am, too, that those saved by me far out-numbered those I hurt – by curing the wounded, and by preventing others from firing at helpless men in the water, as well as by directing my attention, when I did use my rifle, solely to keeping down the fire of their brass gun, which is what we had to fear, for, had they shaken us by their fire, and succeeded in their plan of boarding, not a soul of us would have lived to tell the tale.