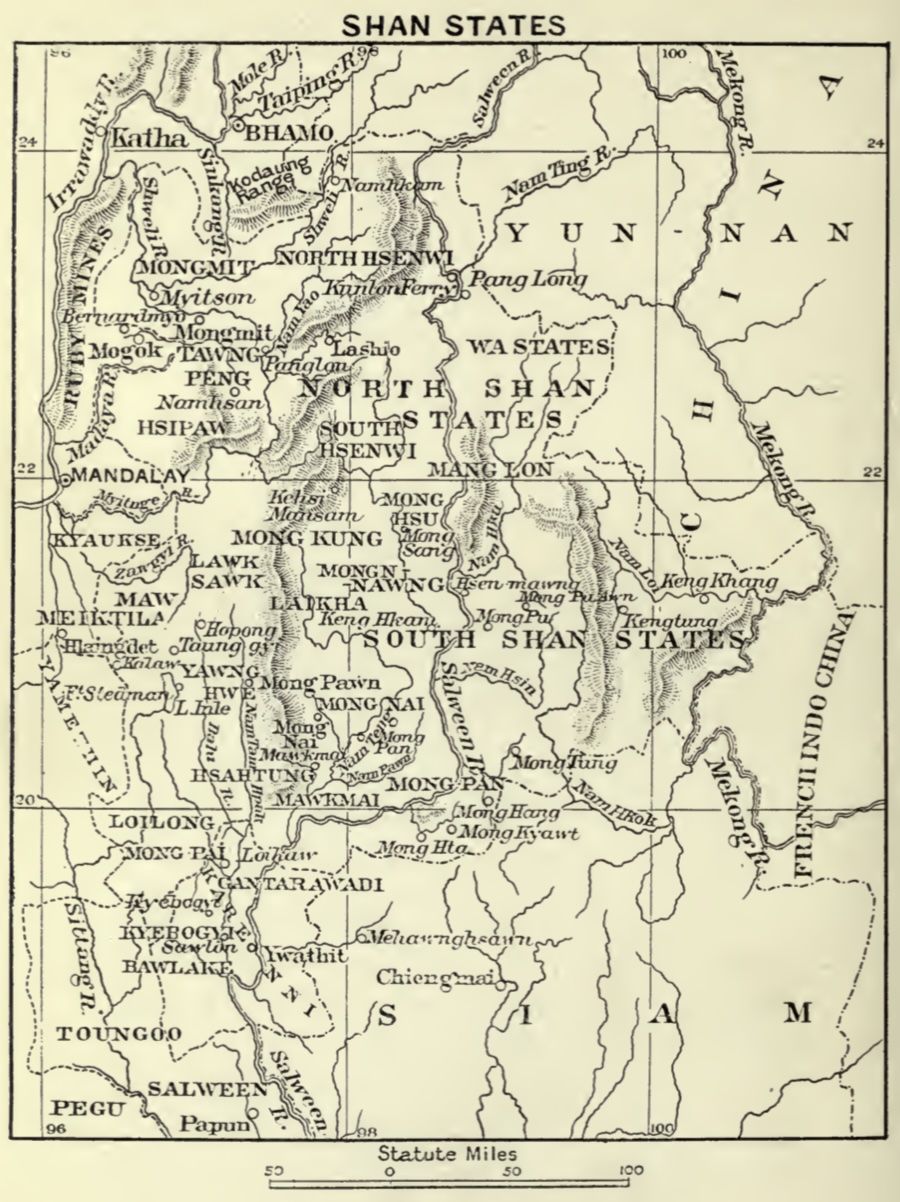

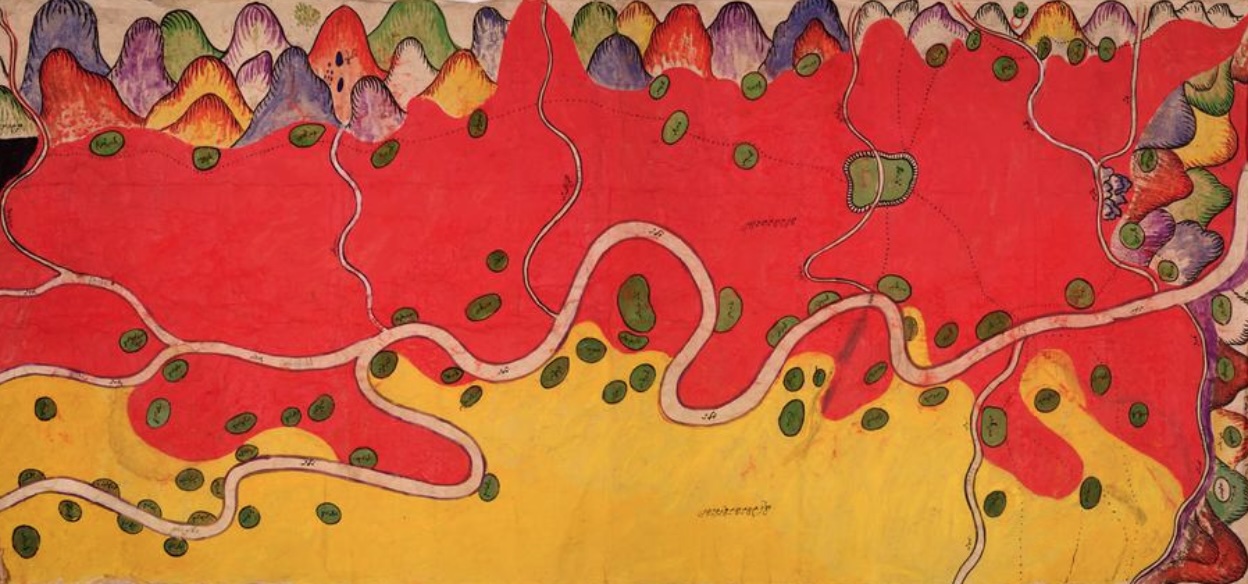

In total, the British Shan States occupied an area of just under sixty thousand square miles, or a little more than that of England and Wales combined. They took the form of a plateau, but one seamed with mountain ranges as high as five to six thousand feet and furrowed with multiple deep flowing rivers. Of these, the greatest was the mighty Salween, which divided the states into two halves, from north to south, and whose depth (as Scott describes it) was sufficient to float the Mauretania or a super-Dreadnought, even in the dry season.

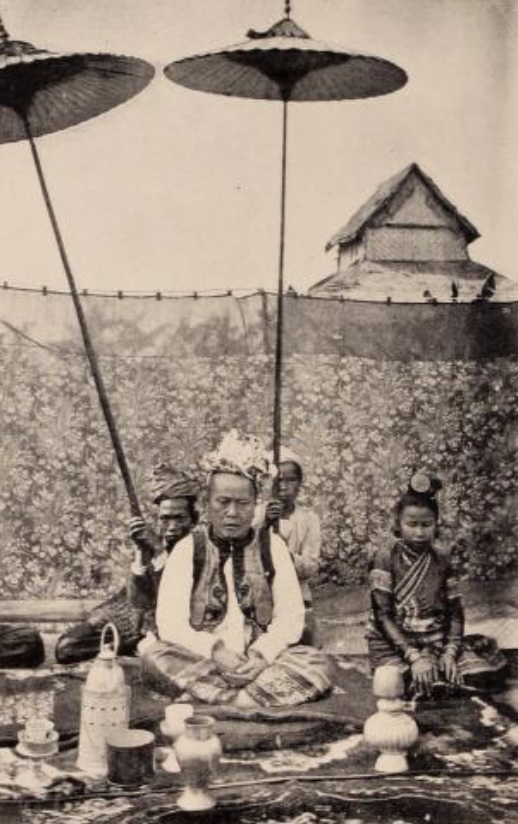

The character of the land greatly influenced the temperament of its peoples, for the barriers by which it was cleaved led to the creation of a number of small principalities, each with a proud sense of its independence. In the British era, there were forty-three of these, excluding those populated by the Wa and the Karens, which were administered differently, or (in the case of the Wa) hardly at all. The Shan chiefs went by the appellations of “sawbwa” (a Burmese corruption of “saohpa”, meaning “sheltering lord”), “myoza” (“town-eater”) and “ngwegunhmu” (“silver tribute chieftain”); which one they bore, had less to do with their importance than with how the Burmese chose to call them “because of their age, or because they had pretty sisters, or daughters in the Palace at Mandalay”.

Scott completes his survey of Shan history prior to the arrival of the British as follows:

The Burmese kings are credited with the policy of splitting up the Shan states, and so ruling them with ease, but such elementary sagacity was not required. The Tai chieftains were as distinctive as the hill was, but they were very far from being one as the sea against an outside enemy. Under Burmese rule they joined the governing power with enthusiasm in subjecting and plundering one another.

The consequence of all the infighting was that, by the time of the British annexation of Upper Burma, in 1886, much of the Shans’ country had been reduced to a wilderness controlled by bands of marauders. In January 1887, a British column marched up and, in Scott’s words, took possession of it “by the mere process of walking through it”. Quickly, the British realised that the patchwork of kingdoms bordering the Salween needed to be properly understood, if trade beyond the frontier with Chinese Yunnan was to prosper. Sir George was the man who – more than any other – put them on the map and, for a period, he helped to end the internal wars of what became the British Shan States. [2]

Early Career as Teacher and Journalist (1880 – 1886)

James George Scott was born on Christmas Day 1851. His father, the Rev. George Scott, a Minister in Fife, died when he was nine, and at the age of twelve, his mother took their son to live in Germany, where he remained until the outbreak of the war between Austria and Prussia in 1866. His elder brother, Forsyth, made a career for himself at Cambridge but, although he went up to Lincoln College, Oxford, George was obliged to sacrifice his place after an uncle lost the family silver speculating in an ill-stared coal mine. Scott wrote,

Red House was shared between my mother and an uncle and aunt. He it was who made a mess of things, so that in the end it was sold. I never knew the rights of it. Uncle Robert had great ideas of coal-getting. A surface shaft had been driven in. The property was bought by a firm of lawyers. It was 600 acres. Much built over now. My mother also had some houses in Earlston, they were sold one by one. Also some property in Edinburgh.

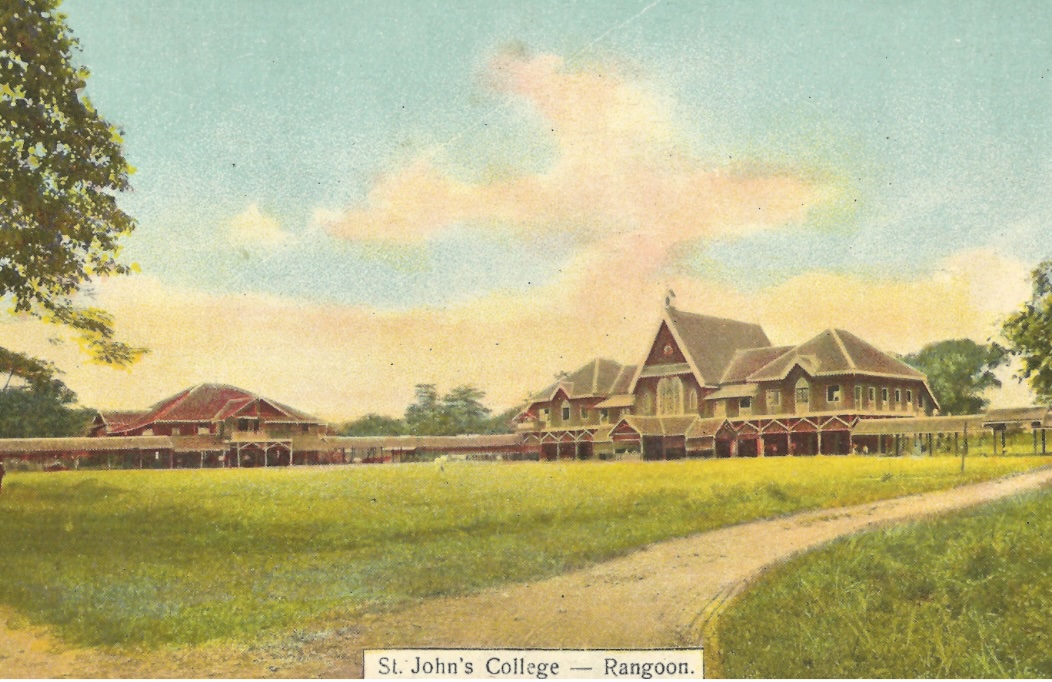

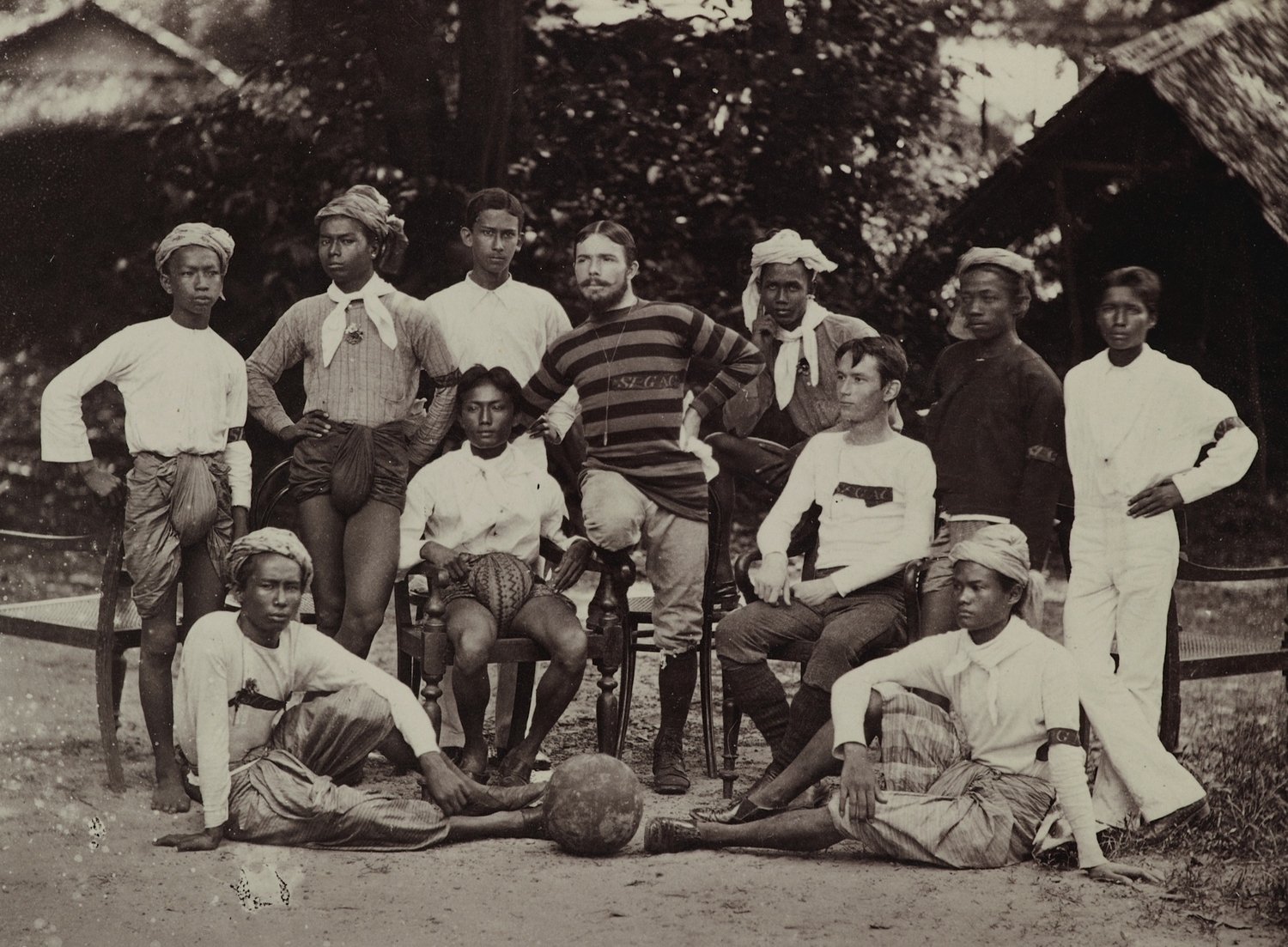

In 1875, Scott was engaged as a special correspondent of the Evening Standard in Malaya. There he covered a brief campaign to punish the assassination of the British Resident at Perak and to win back for Raja Abdullah the throne he had lost to a usurper. To supplement his income, Scott became a teacher at St. John’s College, Rangoon and, in 1880, he became its headmaster. Whilst there, he organised a rowing regatta on the Royal Lakes. Although this was a great success (events such as this had been discouraged, out of a concern that they would foment gambling), Scott is perhaps better known as the man who introduced football to Burma. The first match, between St. John’s and a Moulmein eleven, had a fraught beginning, as the Singapore Free Press reported:

In the punt-about just before the match the ball collapsed, and Scott and the present writer got into a gharry and tore all about the town to raise a bladder, even if it should extend to the purchase and the immediate slaughter of an animal. How Scott did bang the back of that gharry-wallah with that “bust” football to urge him to greater speed, would require an epic poet to recount. A bladder was got from some fisherman or other at last and the historical game was played.

Soon there were regular matches between the British (“The Trousers”) and the Burmese (“The Putsoes”). They became a recurring feature in Scott’s expeditions into, and his administration of, the Shan States:

In the autumn of 1878 three matches were played: “Burmans v. Europeans,” and well-fought contests they were. In the first, the Burmans got well drubbed. In the second the Europeans were left without the services of Jerry Morrison, their goalkeeper, who was ill. Someone kindly consented to take his place. The change was disastrous. The Burmans, who had the kick-off, secured two goals in less than ten minutes, before it was discovered that the substitute, being unacquainted with the rules of the Association game, thought that the ball should go over instead of under the bar …

The Europeans took care to arrange for the third match – the conqueror – to be played when Jerry hadn’t a tummy-ache and they won by two goals to nil after a very hard-fought game.

One spectator kindly remarked it was like goats playing elephants. [3]

At around this time, Scott made a visit to Mandalay to report on the disturbances then besetting Burma’s capital. King Thibaw – described by him as “the most inhuman in a long line of savage despots” – had become monarch in 1878, after an accession massacre engineered by the mother of Queen Supayalat, whom the British troops called “Soup Plate” and he thought a “harridan”, who kept the king “in most humble subjection”. Despite his mother-in-law’s precautions, a succession of omens, including the escape of a pet tiger, which mauled its keeper and set the court scattering, led the soothsayers to recommend the sacrifice of six hundred men, women and children to propitiate the spirits. The panic that followed the first arrests is what Scott was sent to describe. [4]

In one of his anecdotes, Scott told how, during a pleasing study of some girls at the silk-bazaar, he was interrupted by some lottery touts who threatened, at knifepoint, to denounce him as a spy unless he bought their tickets. Scott’s solution to his “rather ticklish situation” was to invite them to a nearby toddy shop and to drink them under the table on Chinese samshu rice spirit and Eagle brandy, “the latter as fiery as a blast furnace”.

The royal lotteries [he reported] lost some money that day; but I did not hang around the bazaar in Burmese dress any more after that experience.

More significantly for his future career, Scott used the occasion of this visit to make his first exploratory foray into the Shan and Kachin (Singpaw) hills. Unlike other travellers of the time, he seemed to find the Kachins sympathetic, even if he was to say that “they were, and where they are not looked after, still are, great cattle thieves, and are as tenacious of blood feuds as the Sicilians or Corsicans”. He describes one encounter as follows:

In the morning, as I was saddling my pony to ride back to Bhamo, there was a sudden discharge of fire-arms, and immediately afterwards a Kachyen, mounted on a mule and recklessly flourishing a long sword, came tearing down to the river. He was rolling in his saddle in a way that suggested a night of debauchery, and I was somewhat disconcerted when he reined right up in front of me and proceeded to load his matchlock. I got near my holsters; but he only fired into the air and then jumped off his mule and came straight up to me. Drawing himself up, he said: “You are a man; I am a man. We are not Burmese. You receive the great Empress’s pay and keep the peace and drink brandy. I serve nobody. I am a chief. I kill the Burmese and the Chinese and take their cattle and I drink rice beer. I am a Sing-paw. Give me some brandy and we will be friends”.

… He was the best swordsman in the hills, he said, and it was necessary to show the spirits of the hills, when a stranger entered Singpaw territory, that he was a friend; and that could only be done by plenty of firing and exhibition of cold steel. Whereupon I fired off my Winchester repeater with one hand and my revolver with the other; and he was charmed and said he would slaughter a buffalo, and we should drink its warm blood together. [5]

Following this encounter, Scott’s judgement was that “A people who drink beer, love rupees, and fire salutes in honour of casual European travellers are neither dead to enterprise, nor dangerously opposed to friendly intercourse. We shall not find them such troublesome neighbours after all”.

By 1882, Scott had accumulated sufficient experience of the country to publish, under the assumed name of “Shway Yoe, subject of the Great Queen”, a book of vignettes of Burmese life called The Burman: His Life and Notions. To further illustrate his style of writing in respect of the tribes with whom we are here dealing, here are a couple of extracts on the Shans and Karens from Impressions of Burma:

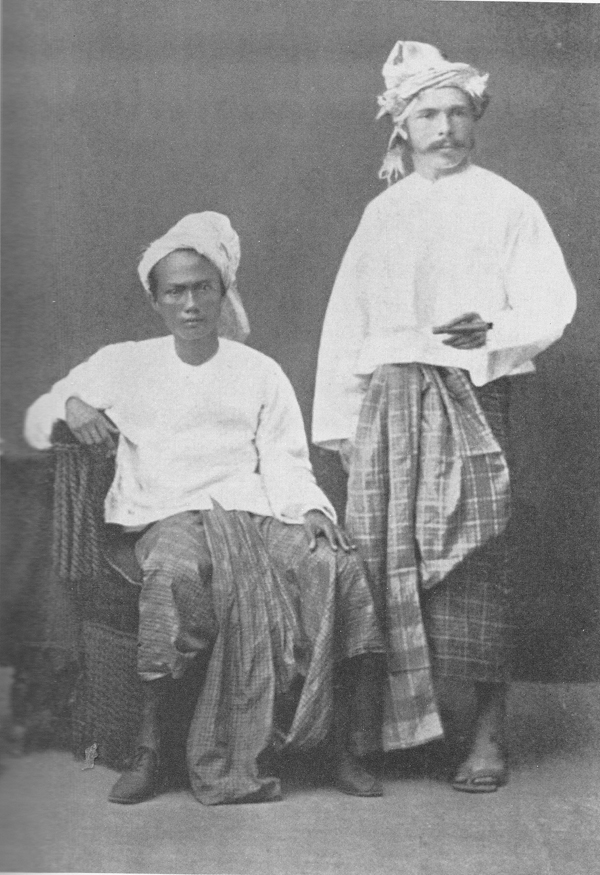

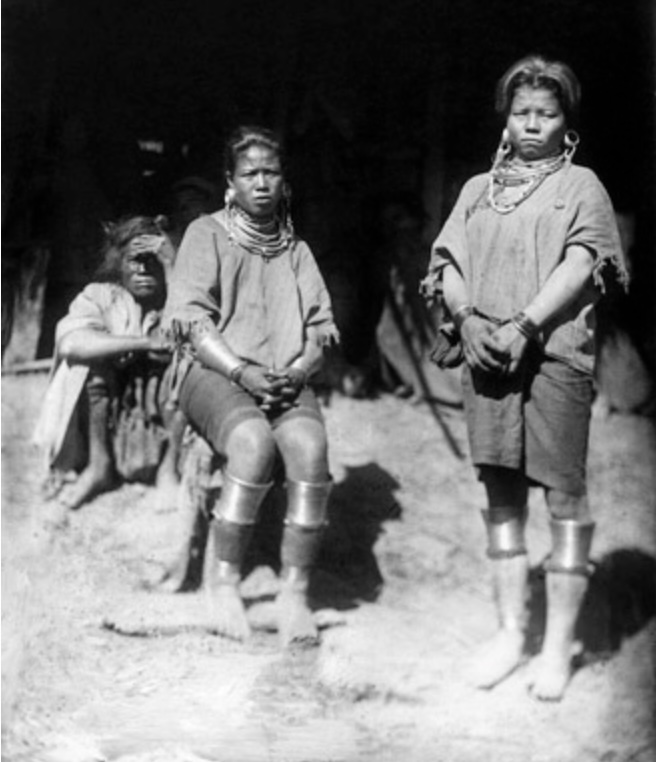

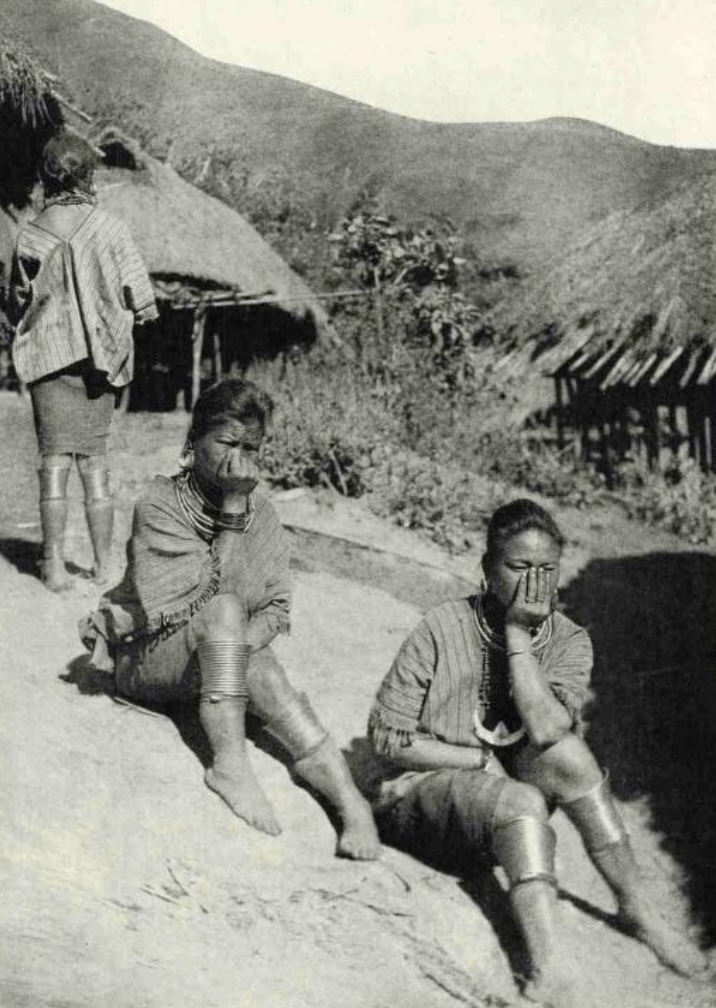

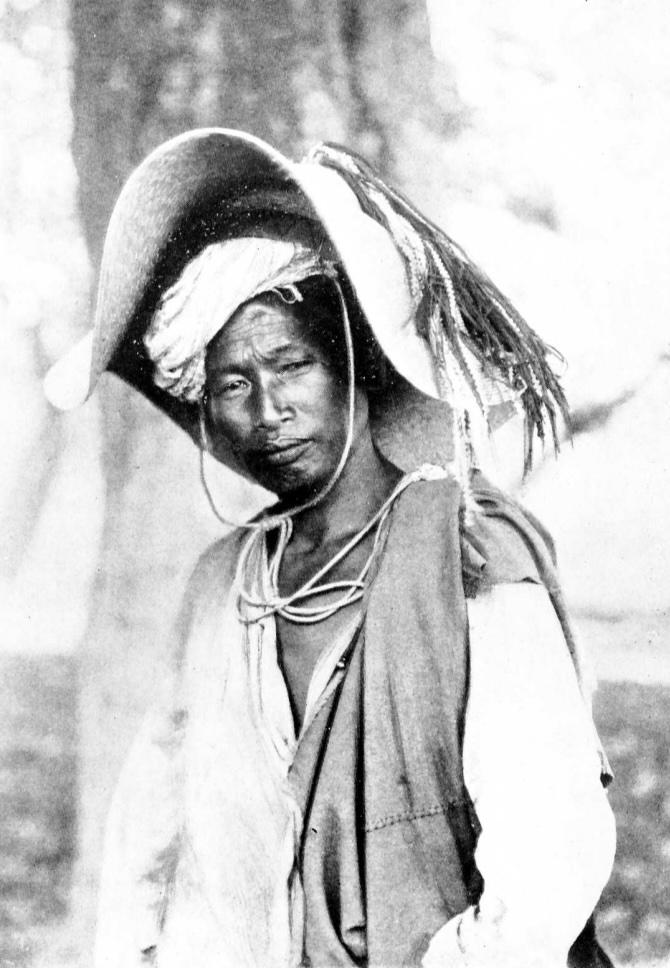

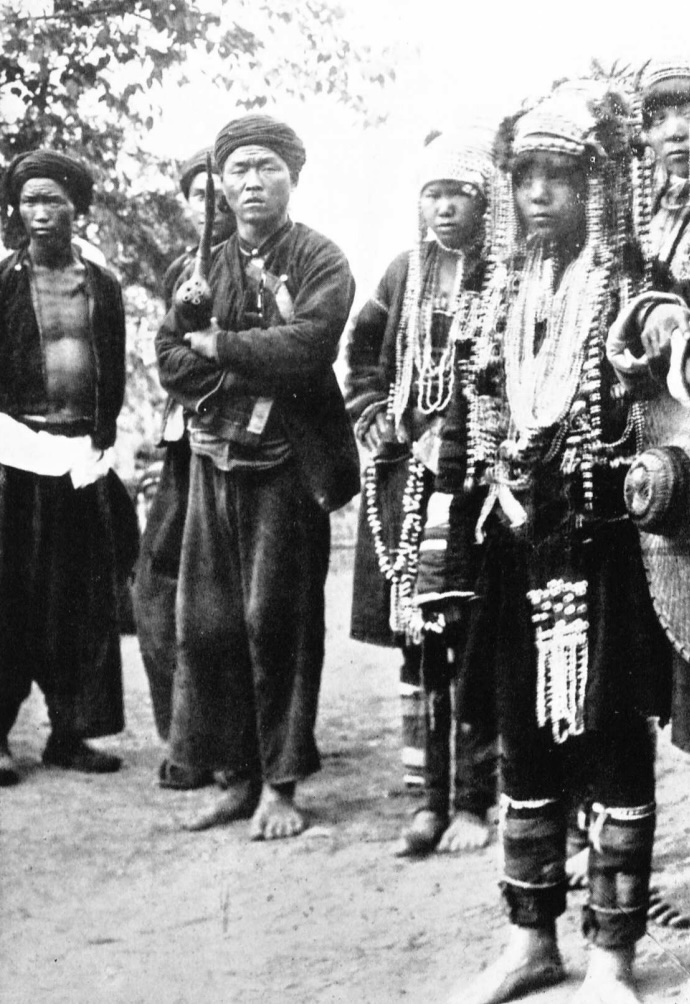

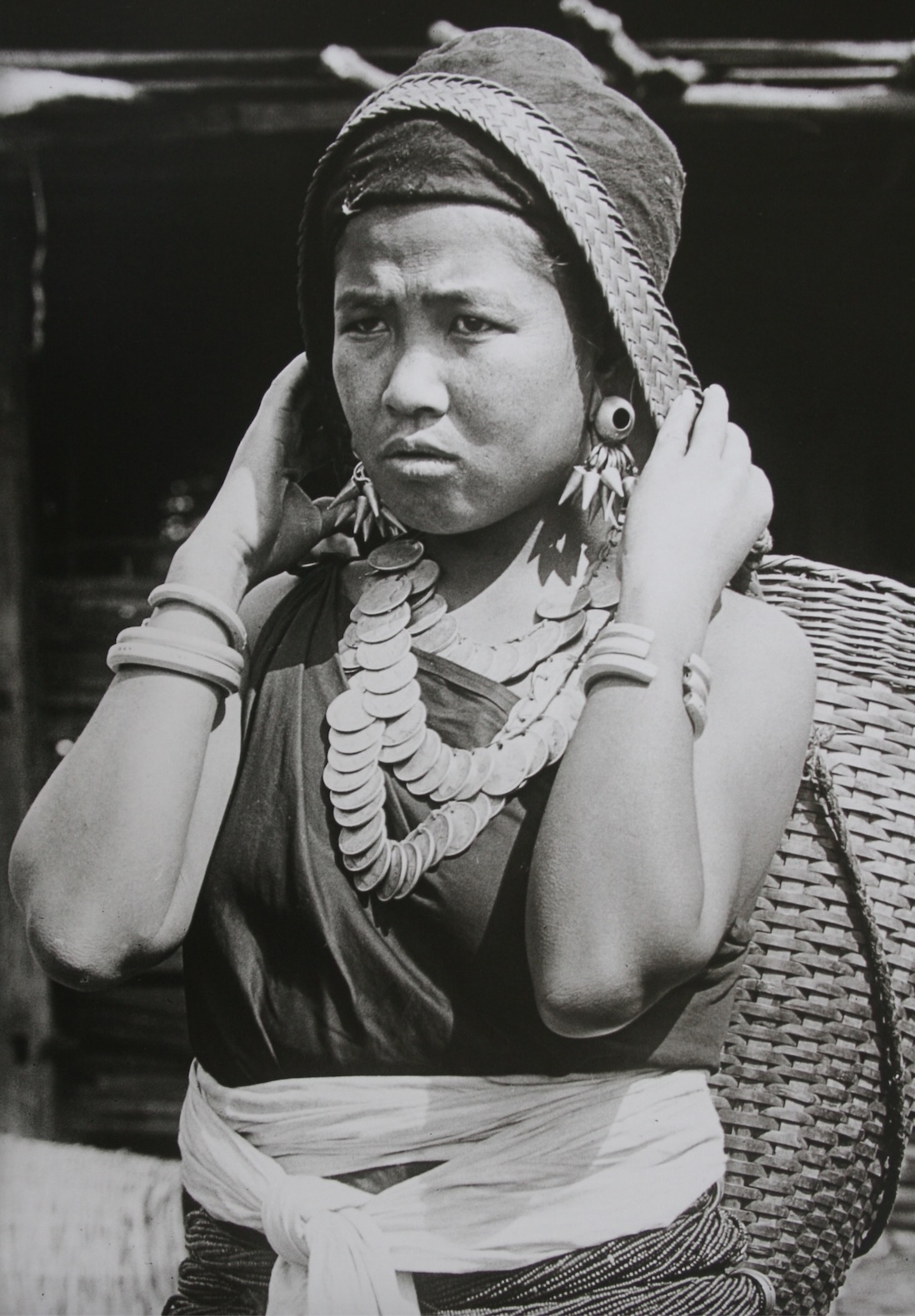

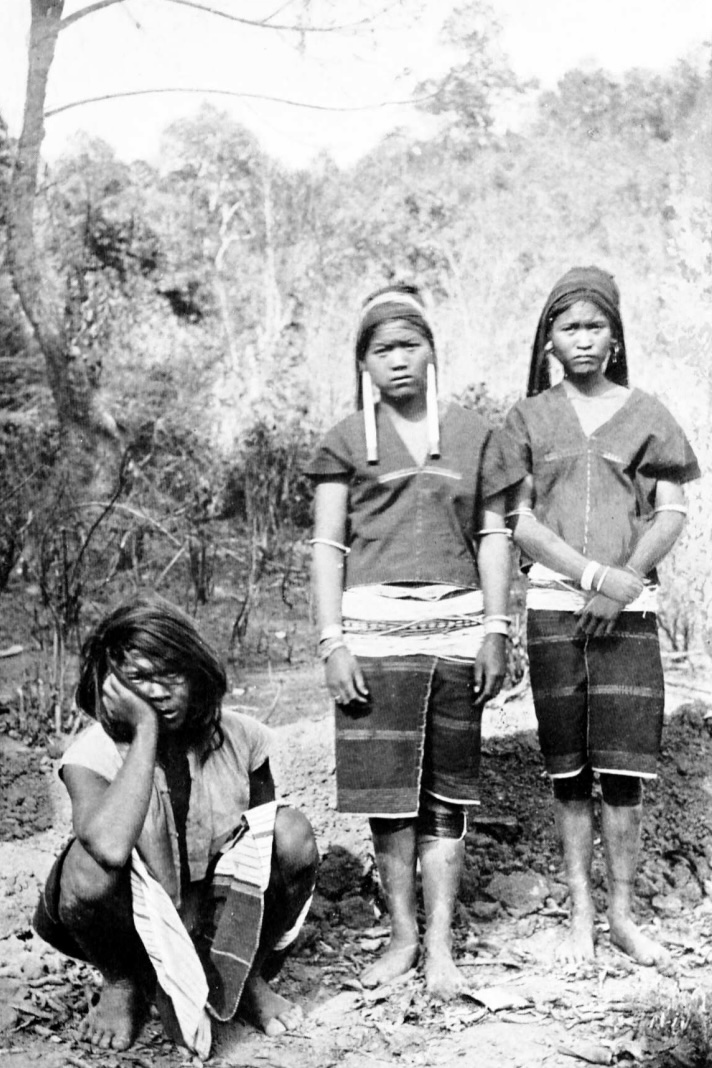

The Shans do not vary greatly in appearance from the Burmese, or from the Siamese. They are less bullet-headed than the former, and distinctly taller and more muscular than the latter, and are, as a general rule, fairer than both. They also differ from both in wearing trousers instead of the petticoat paso of the Burmese, or the dhoti panung of the Siamese. A great characteristic is the broad-rimmed, limp, grass-woven hat. This is confined to the British Shans. Their cousins in China and Siam do not wear it. This is all the more curious because the hats come from China and are not made in the Shan states. They vary almost as much in price and texture as the Panama hat, of which they may be considered a theatrical exaggeration …

… It is for their system of endogamy that the Karens are most conspicuous. In some of their clans their rules are most distressingly strict. Marriages are confined to cousins, or in some cases only certain specified villages may intermarry, and in the extreme case of the Banyangs, neither man nor woman may marry outside of the village fence. It is asserted that, in former days, when nobody wanted to marry, officials came to the village to enforce marriage by judicial order. No British officer has been called upon to perform this invidious duty, so it is possible the village may die out or adopt free love … The women of several clans are quite the most attractive in the States. They are also, in many cases, most strapping wenches, and more powerfully built than their own men. It is possible, therefore, that they may overthrow the old order. If they washed themselves more frequently, it seems likely that they would often be sorely tempted by outside suitors. [6]

Hoping that his book would provide him with the funds to do so, Scott returned to London in 1882 to study law. Unfortunately, it proved less lucrative than he hoped and, by early 1884, he was back in Asia, this time reporting on French activity in Tonkin for the Evening Standard. At the siege of Langson, he met an officer named Nicolle and, in his diary, noted the following conversation, which foreshadowed the explorations he would undertake in the years to come:

Nicolle questioning me about Burma a propos of the capture of Mandalay. Told him a lot of rubbish about some possible route by Hsenwi or Mongnai. May be for all I know. Got greatly excited about it, especially when he found out I knew Burmese. Proposed that he should write to French Government suggesting an expedition from Laokai or Hung Hoa through Luangphrabang to Mandalay “only I should have to call myself French”. Shouldn’t mind doing that if there was a chance of the thing coming off, but Nicolle is a visionary. [7]

The Northern Shan States (1886-1888)

One of the arguments in favour of the British annexation of Upper Burma had been concern over French penetration westwards from Indochina. This was a worry with which Scott found it easy to sympathise. In the book which he published about his experiences in Tonkin, he argued that Britain should make it clear it had no desire to possess itself either of Siam or the Shan states, but that it had every intention of keeping the French out. “Even with the Channel, the silver streak, between us”, he declared, “we find them troublesome enough neighbours at home, and if we had them on our Burmese frontier, they would simply be unendurable”. By 1886, internecine strife between the feuding rulers was wreaking havoc in the states bordering on Laos, and this caused the British to intervene.

Instability came naturally to the Shan states, because of the character of its people. Yet the situation was made worse by the policy of the Burmese kings, who had little to gain from peace and quiet. Their policy was to keep the sons and brothers of the Shan sawbwas with them at Ava, to accustom them to Burmese ways and to make them less sympathetic to their subjects. By becoming more dependent on Ava, they would become more loyal to it. The Burmese also did what they could to foster feuds between rival claimants to the throne. The idea here was that, if it came to force of arms, the victor would be too exhausted to resist Burmese demands. If not, other conspiracies were fostered against him. Unhappily, Scott explains, “such troubles were easily fomented among a hot-tempered, conceited people such as most hill-men are”. It was unlikely that the states had ever enjoyed peace for long. [8]

Given his experience of both Burma and Tonkin, Scott was an obvious candidate to serve in Burma’s east, when the time came. He returned to Mandalay in April 1886, no longer as journalist, but as an officer in the Burma Commission. The first dispute to be resolved was between rival rulers in Hsenwi, a state which then covered some twelve thousand square miles. Even by Shan standards, it was an unusually complex situation.

At the time of the British conquest of Mandalay, the titular sawbwa was Naw Hpa. However, he had been driven out a few decades before by an upstart, Sang Hai, who had risen to prominence when he led an army that repelled a Siamese invasion of Kengtung. For failing to maintain his authority, Naw Hpa was summoned to Mandalay and jailed. There, in the course of time, he was joined by several cadet members of his family, who were sent by the Burmese king to expel Sang Hai and were defeated.

Eventually, in 1877, when confronted by a force from a combination of states, Sang Hai made a tactical retreat east of the Salween, and nominated his son-in-law, San Ton Hung, to take his place. Sensing an opportunity, the Burmese king released Naw Hpa from prison and sent him to reclaim his title. Again, he was defeated but, this time, rather than return to jail himself, he sent his son, Naw Maing, to Mandalay, whilst he personally took refuge amongst the Kachins. San Ton Hung became established in the northern and eastern parts of Hsenwi, while the Burmese official sent to confront him limited himself to “epistolary warfare” from Lashio, and the southern part disintegrated into four petty statelets centered at Mong Yai. Such was the situation when the British arrived in 1886. Scott takes up the thread as follows:

The proper chief of Hsenwi was a young man who went by the name of Nawmaing … King Thibaw kept him as an open prisoner in Mandalay, and when he himself was deported, Nawmaing went up to Hsenwi but found it very much like a bone with a lot of pariah dogs squabbling over it. In addition to pretenders there was a steady pouring-in of Kachins. It is not very easy to see what might have happened had it not been for Hkun San Ton Hung. He was not a Hsenwi man, and was said to have Wa blood in him. He held some petty position as a village head-man. There had been a row over a woman, and he cut down his rival – a petty official – and fled. He made his way to Hsenwi and gathered a lot of Kachins round him and crushed rival aspirants. When Nawmaing appeared there seemed likely to be trouble, but Nawmaing was a colourless sort of youth, whilst the other preferred hills and the ill-regulated Kachins to the more staid people of the lower country; so – in the end – the state was cut in two.

In the letter in which he introduces his negotiations to his superiors, Scott goes some way to explaining his methods of diplomacy:

The mere fact of getting all the chiefs together is most beneficial, and after having once met I dare say they will be less likely to fight. But it is great fun watching them. At first they all camped separately, scattered about over the wide paddy stubbles round about here, now they are beginning to get closer together, and some of them are actually quite chummy. When we have a football match, or when the band plays, they all gather round and even the most stand offish of them are bound to meet. Kun Sang Ton Hung has already got wheeled into line a bit. He has, all his life, been accustomed to being the chief man wherever he was, and consequently the fact of having to wait for an interview, and being patronised when he does get it, is quite a new sensation and has opened new worlds to him.

The Chiefs will want civilising before they are fit for ladies’ society, all except a few. Mone is quite a gentleman.[9]

Unfortunately, although these troubles had quickly been resolved, they shortly spilled over into a dispute involving the neighbouring state of Hsipaw. In 1882, its sawbwa, Hkun Saing, had fled his state for British Rangoon. But he feared assassination at the hands of King Thibaw’s agents and, in 1883, he shot and killed two of his servants, whom he accused of plotting to kill him. He was then much astonished when he was tried and sentenced to death. This was commuted first to imprisonment and then, when he was seen to be suffering his punishment of grinding paddy without complaint, to exile outside British territory.

In 1886, he used the opportunity of Thibaw’s deposition to march to Mandalay and accept British suzerainty. Although he was “absolutely unscrupulous”, in this he had an acute sense of timing. For, as he was the first Shan chief to submit, he was received with a cavalry escort and an eleven-gun salute. They earned him much prestige. But when Hkun Saing returned to Hsipaw, he discovered that it had been attacked by Nawmaing and Naw Hpa, and almost destroyed. (Only his haw, or palace, had survived, and that for fear of upsetting its spirits.)

In the circumstances, it made sense for Hkun Saing and San Ton Hung to combine and form a block to balance the power of Nawmaing and Naw Hpa. In this role, Scott says, they became a force for stability, although at first there was “jealousy and girding” between them:

Sang Ton Hung was a very fine man, though looked upon as a parvenu by others. He was conspicuous among a not very tall race for his height, and as to his muscular build there could be no mistake. Hsipaw referred to him as the dacoit or bandit; Hsenwi retorted by calling him the jailbird. But after a few meetings at Durbars they became great friends. The cognomens were kept on, not in the way of offensiveness, but rather on the lines of Dr Samuel Johnson’s definition, “a term of endearment common among sailors.”

Hkun Saing, who claimed to be “of a family dating back to fairy princes and vampire ogresses”, was a skilful negotiator. Knowing that Hsipaw had strategic value on the trade route to China, he was able to extract rewards for his co-operation by suggesting that the Chinese were courting his friendship. The British therefore connived at his claims on the smaller states of Mong Tung, Mong Long and Hsum Hsai to the extent even of supplying him with arms. However, when he proposed the further annexation of Mong Nawng and Mong Hsu, he was told he would be placing himself “in the position of a rebellious subject”, and this message was taken on board. [10]

The Southern Shan States (1887-88)

Once the disputes in Hsenwi and Hsipaw had been settled, Britain’s attention next turned to the southern Shan states. Scott was appointed to assist Arthur Hildebrand, as political officer at Hlaingdet and Wundwin, right at the western end of the route that he had discussed with Nicolle a few months before. Within weeks he was exploring the eastern hill passes – laborious work, as they had fallen into disrepair during the troubles, or were being purposely blocked by Burmese villagers for protection against Shan cattle raiders, and by Shans who wished to keep the British out.

Scott described the immediate background to the expedition of 1887 in the following terms:

There was a hill chief who was surrounded by enemies. He knew no more of the British Government than any of those who were attacking him, but he was in a very tight place, so he announced his submission to the British Government, and asked to be saved from destruction. He was anything but a respectable old gentleman, but at any rate he was up in the hills and it was necessary to do something there. He knew everybody, and it was convenient to have a starting-off point to tackle the rest of the few score chiefs that were on our eastern front. [11]

The not-so-respectable chief was Sao On, Sawbwa of Yawnghwe (now Nyaungshwe, the tourist centre at the top of the Inle Lake). His opponents included the Sawbwa of Mongnai (Mone), the Sawbwa of Lawksawk and the Myosa of Mongnawng.

Before his deposition by the British, King Thibaw had organised an expedition against Mongnai, and had driven the sawbwa and his friends to seek refuge beyond the Salween River. There they conspired together to overthrow King Thibaw or, if that could not be managed, to obtain independence for the Shan states. It was, says Scott, the vague sort of plot that rather suited the Shan character. Since they could not agree on who from among them could be trusted to lead the effort, the conspirators selected as the figurehead for their movement a junior prince from the Burmese royal house. In Scott’s opinion, he was “rather a lackadaisical person for a Burman”:

He was undoubtedly a son of King Mindon, but not by any recognized wife. She was said to have been a dancer – so far as there were such posturing damsels in the palace – possibly one of the Thami kanya (presentation maidens) sent by the Shan chiefs, or possibly a casual maid of honour. At any rate, she was not conspicuous. This had made it all the easier for the young Limbin to escape the massacre of princes that took place at Thibaw’s accession, and to take refuge in the British legation. From there, disguised in a tameun (a woman’s silken skirt), he was smuggled on board one of the Irrawaddy flotilla steamers and got safely down to Rangoon. [12]

Against the Limbin confederacy there, naturally enough, formed another grouping of those sawbwas who had earlier leagued with Thibaw in his attack on Mongnai and who feared their dominions would be parcelled out to the Limbin’s supporters, as prizes. For a period, they chose as their leader the Myinzaing Price, whom the British had earlier expelled from the Burmese plain, but his death from a fever in 1886 did nothing to ease the situation as, by then, the Myinzaigns were too compromised to expect mercy. For a couple of years, the states were plagued by border raids in which cattle were seized and villages burned. Increasingly, those caught in the middle fled the misery and escaped across the Salween to Kengtung, or to Laos.

Matters came to a head in 1887, when the Lawksawk sawbwa was deposed “by a vague person out of space”. Naturally enough, he turned to the Limbins for support. With their assistance, he got himself nominated to replace his half-brother, the sawbwa of Yawnghwe, on the grounds that he was anti-Limbin. He then corralled together a number of armed parties, and promptly tried to seize it.

By this time, the British had worked out that Yawnghwe was the only really prosperous state in the hills and that its sawbwa was likely to be central to stabilising the situation. They therefore decided they should intervene. This was despite the questionable credentials of their appellant, Sao On, who had himself only just deposed the previous sawbwa, his brother.

Scott reached Yawnghwe with a column of Gurkhas, in February 1887, and was greeted by Sao On, who was seated on a smartly caparisoned elephant. He was flanked by his guard, who were armed with “comic opera weapons, tridents and pikes and spears festooned with horse hair dyed red”. Scott was permitted to ride on another elephant into the town, an experiment which almost went awry when the Gurkhas sounded their bagpipes.

That night, they made an encircling attack on the Lawksawk position, a few miles away on a ridge at Kugyo. In his published account, Scott makes little of the engagement:

Night attacks are always confused and inevitably very slow. When the British party arrived at daybreak intending to rush the Lawksawk camp (it was not much more) nothing was to be seen of the Lawksawk forces – the ridge was empty. The whole band, with the outposts, had streamed off for home, and it was hopeless to catch them up. Our troops marched to Lawksawk and found that the town itself was empty, and the chief had disappeared. All that the mounted infantry could learn was that they had “gone east”.

However, his diary reveals that the assault left twenty-four Shan dead and three soldiers of the Hampshire Regiment wounded. [13]

It had been intended to establish an administrative headquarters at Yawnghwe, but that was now thought to be an unhealthful spot, so a site was chosen on the slope above Inle Lake. Here a fort was built and named after the officer commanding the military force, Colonel Stedman. For, inevitably, the action brought about new involvements.

First, a party of notables from Legya arrived at Mandalay proclaiming themselves servants of the “Great Queen” and offering to help defeat the supporters of Limbin. They complained that the Mongpawn sawbwa was a most dangerous person, and that Lawksawk had allied himself with him. Scott continues,

They had not been gone on their homeward way for many hours when a letter from Mongpawn himself was brought in. He said he was being attacked by brigand bands. He was not afraid of them, but they plundered the poor people, and from a proclamation he had received he gathered the British Government wanted peace. He himself was not an adherent of the Limbin prince, but his great friend the Mongnai Sawbwa was … and he could arrange … and so on at great length.

Letters were sent to Limbin, Mongnai and Mongpawn inviting them to a conference at Hopong. But there were delays. Mongpawn sought to gain time, and Mongnai was attending the marriage of his nephew to a daughter of the Karen-ni chief. He then had to organise the burial of his sister-in-law. Even the Yawnghwe sawbwa was hesitant; Scott’s suspected he was out to make as much money as he could from having the British stationed on his territory.

At last, the British resolved to strike at Lawksawk. The sawbwa fled the column’s approach, and his town was occupied on 11 April. But when, on 17 April, the force reached Hopong, it found it deserted and in ruins. Limbin had not come, and Mongpawn was occupied in defending himself against his enemies. The force moved on to his relief.

When Scott arrived at Mongpawn, he found a line of skirmishers firing “diligently and ineffectively” at its stockade. The troops moved down, and Scott was greeted by the sawbwa:

He was a sturdily built man with a big voice and a confident manner. He said he had heard that the Bo-gyi (great commander) had cannon. He had seen cannon in Mandalay a year or two before, and if he had any himself he would soon have cleared out this rabble, and he could do it now if it were not that there were so many bands he did not know which to attack.

… The racket of firing had ceased as the British approached. The clusters of men on the hills not only stopped firing but some of the bolder bobbed up behind bushes and trees to see what was going on, and the townspeople ventured outside the stockade, but nothing else happened. The Political Officer (Scott) suggested that the Sawbwa should call in some of the attackers to discuss matters or should send someone up. The difficulty was that no one cared to go up, and clearly no one was going to come down.

This weary talking took much time, and never having much use for talking, Scott climbed a small ridge to see how things were going … He took out a box of matches, and methodically lit his pipe and set off to climb up the stockade … To carry on the theatrical business, he stopped as if for a rest and then strolled up to the palisade. This brought quite a lot into the open. When he drew near, he was astonished to see that one of them was a man who had been doing chuprassie (messenger) work in a Mandalay office … It really was comic opera business.

The other chiefs lit cheroots also and explained that they had no real quarrel with Mongpawn. It was simply a case of him having plenty of food, and they none. If they were permitted to depart without being harassed, they would be quite happy to do so. That settled the question.

A small deputation, mostly old men, was got together to go back with Scott to discuss matters. Several were quite well known to Mongpawn, and when they appeared there was some jocose chaff on his part. Mongpawn, it appeared, had got a Martini rifle from somewhere or other, and had become quite a good shot, of which he was very proud. He happened to ask the Legya men if a reckless person who had shown himself outside a corner of the bamboo stockade, at whom he had deliberately aimed, had been wounded. “Wounded,” cried several in chorus. “Dead, stone dead! Shot though the throat!”

The Sawbwa, who had a way of pulling up his wide Shan trousers and rubbing his thighs when he was pleased, did so now, chortling with glee as he polished vigorously.

“I think there were others,” he said modestly, “but I could not be sure.”

Upon this several men from the stockade agreed; they had marvelled to see such deadly shooting. There were four, five, eight, dead or dying, and they gave names and villages in proof of what they said.

When it was brought to Mongpawn’s notice that his enemies were desperately hungry, he gave orders that supplies should be sent to all their people. Scott confirmed that the state of the country was “pitiful”. Between two and three thousand of the people of Legya had died of famine in the previous year, and the majority of the rest had migrated. In the capital just twenty of its original seven hundred houses remained.

While we were on the march here a man in broad daylight tried to carry off one of the Shan pack bullocks, which was out grazing. The bullock men, however, caught him, and after giving him a tremendous beating, brought him up to our quarter-guard. It then turned out he belonged to a village near us which was formerly a very big one, but now consisted of only two houses, with himself as the only inhabitant. We asked the Sawbwa what ought to be done with him, and he promptly said that, according to Shan law, he ought to be shot, and professed himself ready to do it. However, we thought that if the people at home heard that we had put “the whole population” of a village to death there would be a tremendous rumpus, so instead of killing him, we had his head, which was bleeding all over, tied up by the surgeon, and turned him loose with a recommendation not to steal bullocks any more, however hungry he might be.

The winning over of the Mongpawn sawbwa proved decisive in unravelling the confederacy in which he had been the most prominent member. Scott was now able to turn his attention to the Limbin Prince himself, who was sending signals of submission through the agency of his wife (the so-called “Queen of the Middle Palace”) in Rangoon. Scott had actually tutored the prince at St. John’s College and rated him “a lymphatic person and little inclined for war and camping”. He set off on a seventy-mile journey along uncharted paths and through incessant rain to Mongnai. It immediately became apparent that the prince did not like the hills, and that there were only a few of the chiefs he did not consider boors. He preferred the comforts of his rest-house in Rangoon. The negotiations were successfully concluded after Scott conceded to the prince the royal privilege of riding to Fort Stedman on an elephant.

He received great consideration; the band played him in; the sentry posted to keep an eye on him presented arms whenever he went out, which was not often, and he formally “lowered his flag” as he put it. It actually was lowered, and the head clerk who stowed it away safely, pinned on a memorandum: “Alleged royal standard, but really rebel article surrendered by pretend prince, Limbin, as emblem and guarantee of good behaviour, May 1888.”

In May 1887, Prince Limbin went off to Calcutta, where he lived on his pension, as he called it, for nearly forty-five years. [14]

The disturbances at Mongnai took a little longer to resolve. There, Twet-nga-Lu, a defrocked monk, had had himself installed as sawbwa in the disturbed final days of King Thibaw’s reign. “Nga Lu” was the name put against defendants in police charge sheets, and therefore it implied “a negligible, if not a suspicious character”. But Twet-nga-Lu was not someone to be trifled with. Like many monks, he dabbled in mystic arts, and he had a sinister reputation as a necromancer. He was also familiar as a dealer in charms, talismans and incantations, and as a tattooist is of “most pretentious abilities”.

Hence he drew to him the scum of the States; novices in guilt, who wished to be made proof against wound of bullet, stroke of sword, or thrust of spear; and captains in crime who recognized in the uncowled monk and dethroned prince a desperate man who would point the way in many a raid where spoil was to be gotten, and who could moreover add another potent charm or two to the amulets already embedded beneath their skin, another red cabalistic scrawl to the rimes which decorated their chests, backs, and arms.

After Thibaw’s fall, this “son of a Salween boatman” was driven out of Mongnai by its rightful ruler, Kun Kye. He came to Fort Stedman to make his case but convinced no-one. The British were persuaded both that Kun Kye’s claim was true and that he had the overwhelming support of his people. Twe-nga-Lu was sent packing, and he went over the border into Siam to collect together a force.

Then, in May 1888, as Scott was escorting a company of men in the vicinity, he encountered a group of refugees who claimed Twet-nga-Lu’s “dacoits” were putting Mongnai to the torch. Taking with him just six men, Scott made a dash for it. He reached Mongnai in the dawn mist (there was no fire) and, stealing through the open gates of the palace enclosure, he took the “chief” by surprise:

Everybody seemed to be asleep. There was nothing in the shape of guards or sentries, but a sleepy townsman, as they came into the gate, pointed out the detached building where the “chief” might be found … Scott knew Twet-nga-lu by sight, and happily recognised him on his bed in the veranda above. He raced up the stairway and found him just aroused and reaching out for his magazine rifle, which was beside him.

The whole thing had been brought off so quietly and quickly that he was entirely off his guard. He knew Scott, too, having seen him a week or two before at Fort Stedman, and recognising that he was fairly caught, he said: “Don’t let the Gawya shoot; I’ll come with you.”

“The Gawya,” otherwise a British soldier, grabbed him by the arm and cried: “All right, old cockywax, you come along o’me,” and pulled him down into the open courtyard round which the palace buildings stood. He was there secured.

Six of his leaders, “all notable banditti”, were sentenced to death and shot. Twet-nga-Lu himself was taken to Fort Stedman as a prisoner, where it was decided he should be tried by his fellow chiefs. Scott says it was fortunate for him that he didn’t reach Mongnai again. He tried to escape on the way back and was shot by a Baluchi guard:

But that was not quite the end of him, for the body, having been buried, was dug up again by his compatriots, and from under the skin were extracted the numerous talismans and charms inserted to make him invulnerable. These found a ready sale. Then his head was boiled down to make a decoction of physic to give courage. Phials of it were actually sent to the Chief Commissioner in Rangoon … but were declined. No doubt the other Sawbwas were glad enough to buy samples, and so Twet-nga-Lu was very completely disposed of. [15]

Scott wrote that these events proved to the Shans three things: that the British would support the rulers they had confirmed in their state, that they would not manipulate rebellion as the Burmese kings had done, and “that the most potent charms, cantraps, cabala, or telesms were of no avail against the whiz of a British bullet”. Of the three lessons, he suggested the last was the most powerful agency for peace. In the following five months, Hildebrand took a force around all the fiefdoms remaining to the west of the Salween, and confirmed their sawbwas as tributary chiefs. Not a shot was fired. Scott did not accompany Hildebrand, although he was responsible for much of his planning. On the other hand, he was present at the submission of Mawkme.

Its sawbwa had been known as the “Five Cubit Potentate” because he was said once to have leaped that height. This, it was said, was certainly “a very unusual feat for a Shan and still more for a chief, whose idea of dignity is to take as little personal exertion as possible”. When Scott arrived at his village, however, the potentate was most inanimate. In fact, he had died that morning. Scott received his son as successor. He then paid his respects to the deceased sawbwa, as he lay in state surrounded by the women of the palace. He writes,

There was a musical box at the head of the bier which played, “Red as a Rose is She” and “There’s nae luck aboot the Hoose,” and another at the foot which repeated, “Don’t make a noise or you’ll wake the Baby” and “It’s a Pity to waste it,” with inexhaustible energy. They both played at the same time to the great pride of the mourners, and there were a number of palace maidens there with fans to keep the flies away. [16]

The Trans-Salween Shan States, Kengtung (1889-90)

Since the border of British Burma now abutted China to the north and Siam to the south, there were now new issues to consider. In his account, the Chief Commissioner of Burma, Sir Charles Crosthwaite, says that, at first, there was no appetite for claiming the territory beyond the Salween, which served as a natural and easily defended boundary. The country was mountainous, unhealthy and unprofitable, and the costs of even a small administering force were likely to be significant. Nor, he says, was it desired to bring British Burma into direct contact with French Indochina, or to offend Siam (which he called “that somewhat unreasonable power”).

On further reflection, however, it was felt that Britain’s new subjects, whether in Burma proper or the Shan States, would not appreciate her stopping short of the frontier claimed by the Burman kings. The British might profess, as their motives, prudence and forbearance, but they were likely to be accused instead of fear and weakness. Nor were the Trans-Salween states judged capable of defending themselves. And whilst they might invite in China or Siam, China was thought too disinterested and Siam too feeble to protect them against the incursions of brigands like Twet-nga-Lu, or (worst of all) France. It was possible, therefore, that inaction might bring about precisely the frontier with France’s dominions that Britain was keen to avoid. [17]

In March 1889, a force from Chiang Mai crossed into the Trans-Salween districts of Mawkmai and claimed them for Siam. The British responded by forming a commission led by the explorer Ney Elias, to fix the border. Scott served under him. An appointment was made to meet a delegation from Bangkok at the river crossing at Ta Sangle. The Siamese, however, failed to appear. Crosthwaite speculated on their reasons as follows:

Whether this was a deliberate act of discourtesy, or only a failure caused by the general debility of the Siamese administration, may be questioned. Most probably it was an instance of the common policy of Orientals and others with a weak case, who prefer to plead before a distant and necessarily more ignorant tribunal, rather than to submit their statements and evidence to a well-informed officer on the spot. [18]

Scott now prepared to accompany Elias on a survey of the Karen-ni country, but they were too much alike to get on well. When, in February 1890, he was given the opportunity to settle independently the status of Kengtung, on the approach to Laos, Scott went only too willingly.

Kengtung, which covered an area as large as Belgium, had thrown off Burmese control in 1882 and had since enjoyed eight years of independence in relative peace and tranquillity. Scott himself considered that its villages offered a study in contrasts with the misery and depravation that had arisen as a result of ten years of anarchy in the Cis-Salween states. The state itself, however, was thought to offer limited economic value. According to the Pall Mall Gazette, it was populated by as many tigers as people, and they were of a most primitive kind, dependent for food on what they could kill with their bows and spears. Certainly, Kengtung itself explained that it had no great desire to receive Scott’s mission:

By the favour of the Chief Commissioner and the Superintendent our State is at peace … Chinese military officers [are] coming down … Kengtung is a remote and insignificant state situated on the border land, and if a large force advances on it from both sides it will be unable to withstand and must allow itself to be destroyed … We are obliged to ask the Superintendent to postpone his visit to Kengtung. [19]

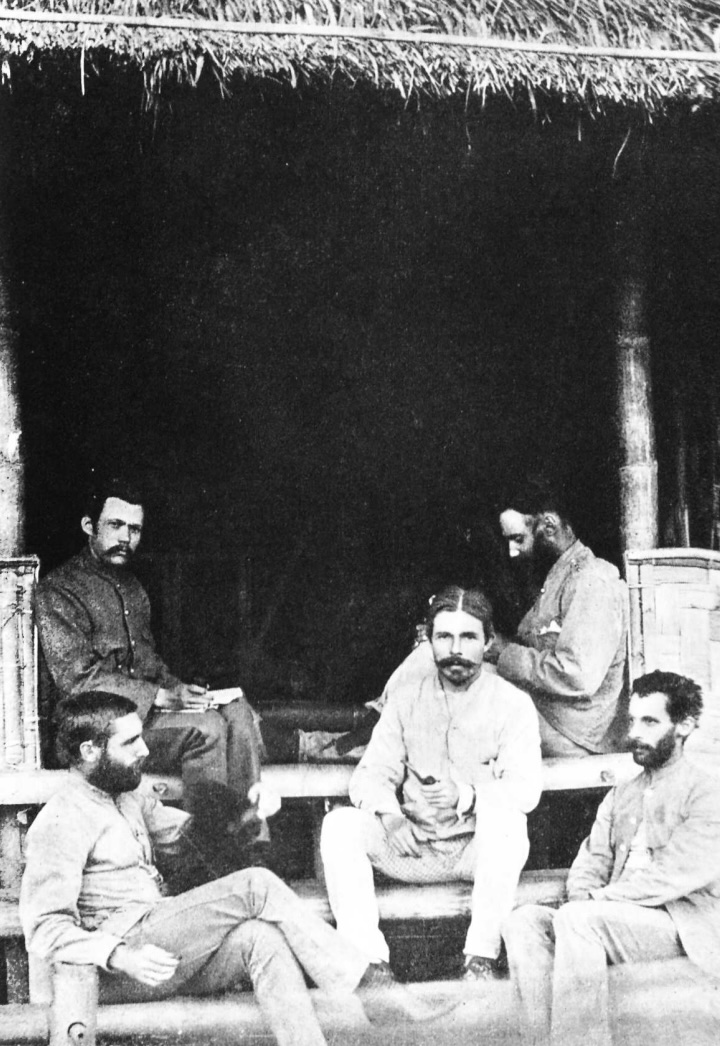

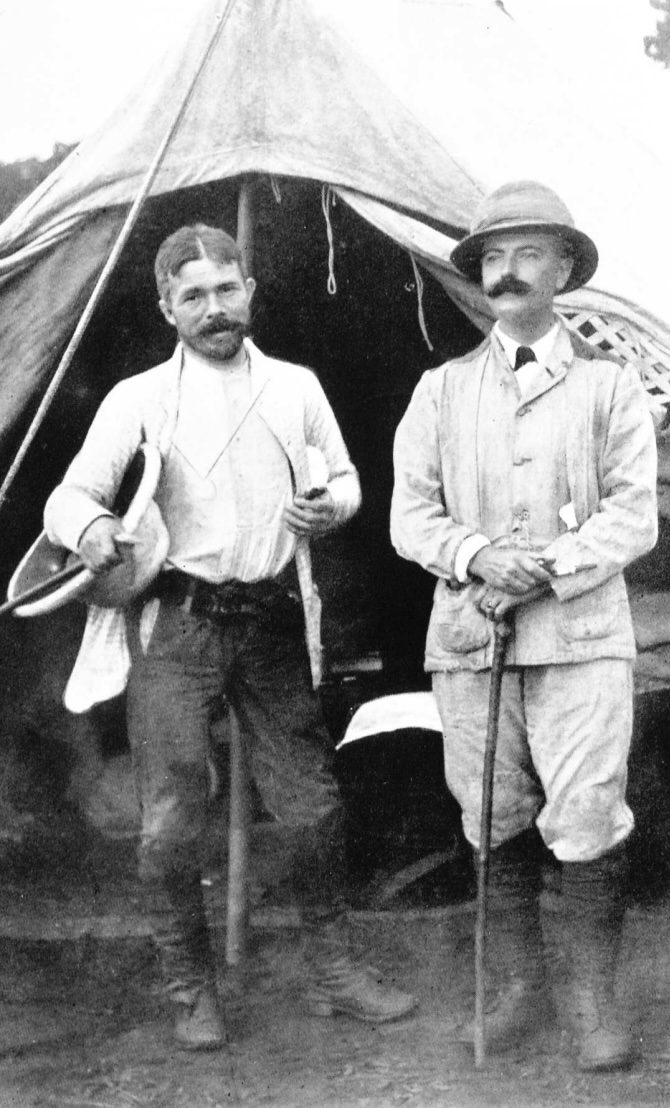

Despite their pleas, the British decided their interests demanded that a mission be sent. Scott assembled a party of fifty men, including two Britons, a medical officer and Captain FJ Pink, DSO, who was put in charge of an escort of untrained troops; “rough spear-men to give a touch of romance to the cortege”, as Crosthwaite described them. Out of a desire to be discreet, Scott suggested to Pink they take as few Gurkhas and Pathans as possible; the Gurkhas, he warned, were always looking for a fight, and the Pathans were peculiarly sensitive to supposed offences against their dignity. The result, Crosthwaite conceded, was “not a very imposing embassage, certainly, to represent the majesty of England, and to require the allegiance of a chief who ruled over twenty thousand square miles of country”.

Although there had been four or five Europeans who had visited Kengtung in the previous century, Scott’s group was the first to do so from the west and the journey was a difficult one – made more so by a desire to evade any Kengtung delegates sent to intercept them. Its destination was 250 miles beyond the frontier, there were no roads, and three significant mountain chains had to be crossed:

Part of the way ran along the side of a precipice. The ledge to be traversed was so narrow that the mules, striking their loads against angles, were many times in danger of being driven over the outer edge into the precipice below. When this did happen the beast, of course, had to be left where it fell, pack and all; it was irrecoverable. [20]

For part of the journey, Scott was accompanied by the Myoza of Keng Hkam, a state that had suffered terribly at the hands of Twet-nga-Lu. According to Crosthwaite,

His avowed object was to improve his mind by travel, and to learn English modes of procedure. It afterwards, however, appeared that he was attracted more by the fame of the charms of a lady of the Kengtung Royal Family than by a craving for knowledge. “He was successful in his wooing,” wrote Mr Scott, “and it may be hoped that his bride will put an end to the habit which he is developing for making inconsequential set speeches. Otherwise he is in danger of becoming an intolerable young prig.” [21]

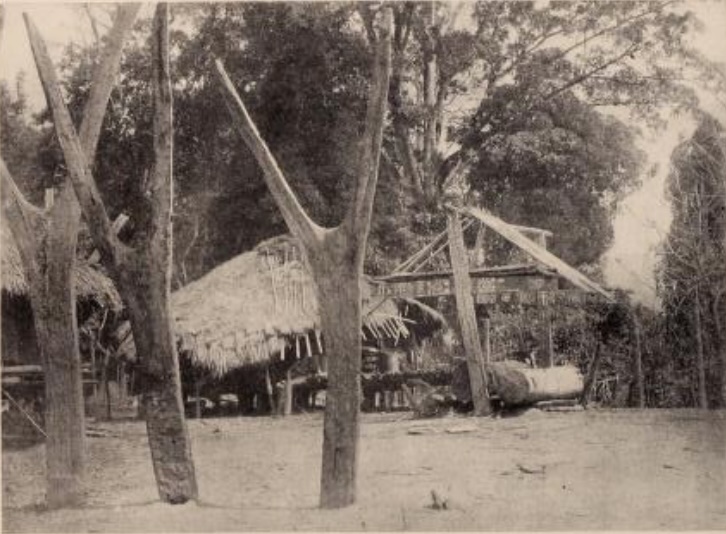

In March 1890, the party arrived in Kengtung and settled in the compound that had been the Burmese post. The city was situated on a plain estimated by Scott (contrary to the opinion of the Pall Mall Gazette) to be home to a population of twenty thousand. However, the eighteenth-century walls were “picturesque rather than formidable” and they were overlooked by hills that were so placed as to enable those equipped with field guns to drop their shells wherever they pleased within the town’s precincts.

In Rangoon, the reputation of the Kengtung Sawbwa was not a positive one:

His father had been a distinctly murderous old ruffian, who sat in the gallery or vestibule of his palace, and picked off such of his subjects as were reckless or ignorant enough to come within range. His magazine rifle had been presented to him by the “Foreign Power” that the Rangoon Secretariat did not like, and it was not clear from whence he got his cartridges. The son, the then Sawbwa, was said to be very much of a lout with a great opinion of himself, naturally fostered by his ministers, and with aspirations to become as successful a shot as his father, but otherwise undeveloped. [22]

On his arrival, Scott confirmed an unfavourable impression in his diary:

The ordinary Shan type of face is not handsome and it requires a pleasant expression to make it even passably engaging, rather than brilliant-hued satin coats, gold-bespangled trousers, with a dado pattern around the bottom, gorgeous slippers with the toes turned up mediaeval style, and diamond rings and ear-cylinders. The Sawbwa has the usual heavy jaw, the extremely prominent cheek-bones, lips more than usually protruding, nose more than usually sketchy, eyes set nearly flat with the forehead, with an expression that is instantly repellent … On this face the struggle between conceit, which had never before met anyone not an inferior, a desire to presume, yet a fear of consequences, and a natural dullness of brain, which rendered ideas scarce, produced an unpleasing effect. He hardly said a word except yes and no. [23]

It was unfortunate that, on the third day, some muleteers from the British party, who had gone off in search of cheroots, got involved in a fight with some of the sawbwa’s men. Shots were fired, one of the muleteers was killed, one was badly gashed with a dah, and another went missing.

Scott dispatched a letter of protest, demanding the culprits be punished. He then learned that the man the drivers summoned up the courage to denounce was the sawbwa himself. Indeed, “they had seen him firing shot after shot into [the muleteer] as he lay on the ground”.

British prestige and the safety of the party necessitated a firm stance, and for the case to be settled according to established procedure. Scott therefore arranged a meeting with the sawbwa’s chief minister, an old gentleman “with a soapy manner”. The minister explained that the sepoys had come into the palace yard carrying arms, which was strictly forbidden. Some of the sawbwa’s retainers, whom he conceded were rather undisciplined, had perceived a plot and had acted “rather hastily”.

Scott countered with the argument that their only arms had been the dah which, he said, everyone, even children, carried. In accordance with local custom, he therefore demanded financial compensation as well as the return of his missing muleteer:

“Just as well to settle it now,” said Scott. “Three hundred rupees, isn’t it, for a man of position? Lao Pan (who had been killed) was temporarily in the service of the British Government, which is a distinction. As to the wounded man the civil surgeon will estimate the damage. But both figures will have to be doubled to prevent more mischief. The Bo-gyok here”, he pointed to Pink, “says that there have been too many people loitering round at night, and they don’t reply when they are challenged. Twice three hundred – well, we’ll say five hundred for Lao Pan, and perhaps half that for the wounded man.”

“It is unheard of,” wheezed the minister. “Five hundred rupees for a mule driver?”

“Well, if we catch the murderer you may be sure we will hang him, whoever he is.”

There was an uneasy movement in response to this among the minister’s following, who squatted on their hunkers behind him. This showed clearly that the Sawbwa was the culprit.

“Tell the Sawbwa that the Bo-gyok and I will come to the palace tomorrow, and everything can be settled then.”

For the occasion, the sawbwa, who had heard of the British army’s predilection for drill, suggested a display be performed in the palace grounds. Scott recognised the risks, but decided he was in no position to refuse. Ostentatiously showing he carried no arms of any kind, he sat beside the Kengtung ruler, but he made sure he was accompanied by one of his Affridi orderlies. The orderly, he says, certainly was not unarmed and, afterwards, he declared that his presence had saved his life:

The volley-firing interested the chief, but he suggested the use of ball cartridges, and offered to point out individuals in the crowd of townspeople below whom he would least miss if they were picked off. He was especially interested in the issuing of orders by bugle call, and wanted to buy the bugle and bugler there and then. He sulked when he was told it was impossible, but that if he came to Rangoon he could buy all the instruments he wanted, and much noisier ones. He tried the bugle himself, producing hoarse blares, to the disgust of the Sikh bugler, who spent the rest of the day cleaning and polishing the mouthpiece.

The Sawbwa got more and more bored and pettish, especially when Scott refused to go out into the open country, where, he said, they would find stray cultivators in the fields, who would make excellent marks at various distances. The Chief offered to go himself and show what he could do, but he added that his stock of cartridges was getting low, and he did not know where he was to get more. [24]

Despite these disappointments, the display of firepower was sufficiently convincing to enable Scott to persuade the sawbwa of the sense of submitting to British authority. The sawbwa treated the idea with “imperturbable nonchalance”, he wrote,

He had nothing to say against it, and saw no particular advantages in it. I had to argue in every way I knew until, at last out of sheer boredom, he agreed that a covenant should be drawn up. [25]

According to the terms of the settlement, the sawbwa promised to pay the same tribute to Britain that he had paid before to Burma, to accept the chief commissioner’s advice on internal and external affairs, and specifically not to communicate with foreign rulers – by which Britain meant China, Siam and, especially, France.

The swabwa died within a few years. He was succeeded by his younger brother, one of whose first actions was to order a bicycle:

It had to be carried for a great part of the way on men’s shoulders. When he got it, [Scott wrote] he had it gilt all over so as to be seemly for royal riding, and then did trick cycling in the palace where the wide spaces were very suitable. His son has been educated in England, and is a most promising youth, so progress marches swiftly. [26]

It is at this juncture that Dora Connolly, the first and most remarkable of Scott’s three wives, appears on the scene. In a certain peculiar way, however, she does not. It is an indubitable fact that they were married in September 1890 on Scott’s return from Kengtung, and it is clear – if only from his reaction to her death – that he was very much devoted to her. Yet, strangely, she gets barely a mention in his travel journal, even though she followed in his footsteps (at considerable personal hardship) for much of the coming six years.

To start with, however, she remained at home at Fort Stedman, whilst he headed across the Mekong, to Mong Hsing, capital of the state of Kengcheng. Its ruler offered to submit to Britain, but Scott was not authorised to accept:

In the beginning of 1891, when I met him first, [the Myosa] was eager to accept, or rather to claim, British protection, and offered to hand over to me the gold and silver flowers formerly paid as tribute to the Kings of Burma. This he thought would be a protection to him against Siam, which during the previous eighteen months had been threatening him with punishment or expulsion if he did not submit.

… I had no authority in 1891 to accept the tributary offering, and I was aware that the Government of India was altogether disinclined to extend its responsibilities beyond the Mekong. I therefore told the Myosa to keep his gold and silver flowers until he received the direct orders of Government.

When, therefore, in the season of 1892-3, the myosa was informed by Scott that the British government was renouncing its rights over Kengcheng in favour of Siam (and this at a durbar at which the Siamese were not even present), he was greatly surprised. He was not to know that Britain had come to an agreement with Siam, from which it received, in exchange, parts of east Karen-ni that were rich in teak.

For its part, however, Britain had not appreciated that Siam was about to be pressured into ceding Mong Singh, and all the territory east of the Mekong, to France. When it learned what had happened, another expedition was sent to demarcate the frontier afresh. Told that he now needed to tender a nominal tribute to Britain, the myosa was completely non-plussed. Sensibly, he questioned why the Siamese were not signalling their agreement, and he pointed out that, whereas Siam was on his doorstep, British power was “far”. If he did what he was asked, and the Siamese took exception, “ruin to himself and to the State stared him in the face”.

In January 1895, Scott and the French explorer, Auguste Pavie, met at Mong Hsing to hammer out an agreement on a buffer state. But they were unsuccessful, and the argument between the two governments rumbled on, over the myosa’s head, until January 1896, when the Mekong was fixed as the boundary. Scott was unimpressed. Lord Salisbury was, he wrote, “without exception, the worst Foreign Secretary we ever had for matters east of Suez”.

In 1891, Scott travelled from Kencheng to Kenghung (now the Chinese region of Xishuangbanna) in the hope Britain might be persuaded to claim its allegiance. Again, he was disappointed. Another objective of the journey was to report on the activities of the French and, in particular, of Pavie, who was stationed at Luang Prabang. “Of that gentleman and his movements”, he wrote, “we could hear nothing … the rumour that the energetic Frenchman was to visit Kenghung this season was premature”. This was one of Scott’s least prescient reports. Pavie reached Kenghung just six weeks after Scott left. [27]

Superintending the Northern States – the Wa (1891-1901)

On his return to Fort Stedman, in August 1891, Scott was next directed to Lashio, where he was to serve as superintendent of the Northern Shan States. This time, Dora went with him. Their subsequent tours together were impressively ambitious. In 1891-2, they traversed the now infamous district of Kokang, before exploring the Kachin-China border zone. The following year, they crossed the Salween to assist the sawbwa of Manglun, who had asked for help in putting down a rebellion. Scott noted in his diary,

8th January 1893, Takut. We called on the Sawbwa before breakfast. Palace small and almost unfurnished but solidly built of oak and pine. Old mother produced: said to be ninety, very lively and domineering for that age. 12 dried squirrels, dried fish, bamboo roots and mustard leaves presented as tribute along with 59 Rs and a small stallion. Photographed the old man, his wife and mother. [28]

Scott later encountered Manglun’s regional overlord, the sawbwa Ton Sang, at Loi Lon. Disturbingly, on the occasion when the Scotts first arrived, they found the entrance to this village blocked up with coffins. The principal house had evidently only just been vacated, as there was a fire still lit within it, but most of the villagers had fled. Scott allowed the few that remained to take some photos with his camera, and this helped to settle things. On the following day, the village headman returned with Tong Sang and a large population. Scott arranged for a sort of durbar and sports event:

All the headmen of the state excepting the Shans of Na Fan came in to the meeting and the whole hillside swarmed with armed men. The discussion was very long and noisy, and was conducted almost entirely in Wa … There was at the end a great chanting of ritual by the elders, a passing backwards and forwards of fowl’s legs and pigs’ hams, and finally the slaughtering of a gigantic buffalo which the meeting ate.

The sports in the afternoon were equally successful. In each event the sepoys tried first and then the Wa. There were two greasy poles with three rupees on the top of each, and both Wa and Sepoys were untiring in their attempts. At tea-time Ton Sang ate bread and jam for probably the first time in his life. In the end I threw two-anna bits among the crowd, and ended up by throwing also the rupees which had not been won from the posts. There was a seething mass; there must have been quite 1,000 people present. [29]

After that, Mr. and Mrs. Scott embarked on an eye-opening, seven-week tour of the Wa territory, penetrating much further than any other European had done up to that point.

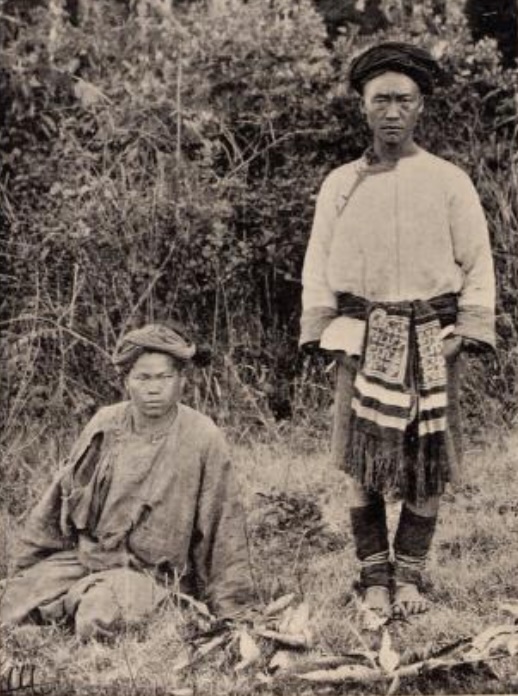

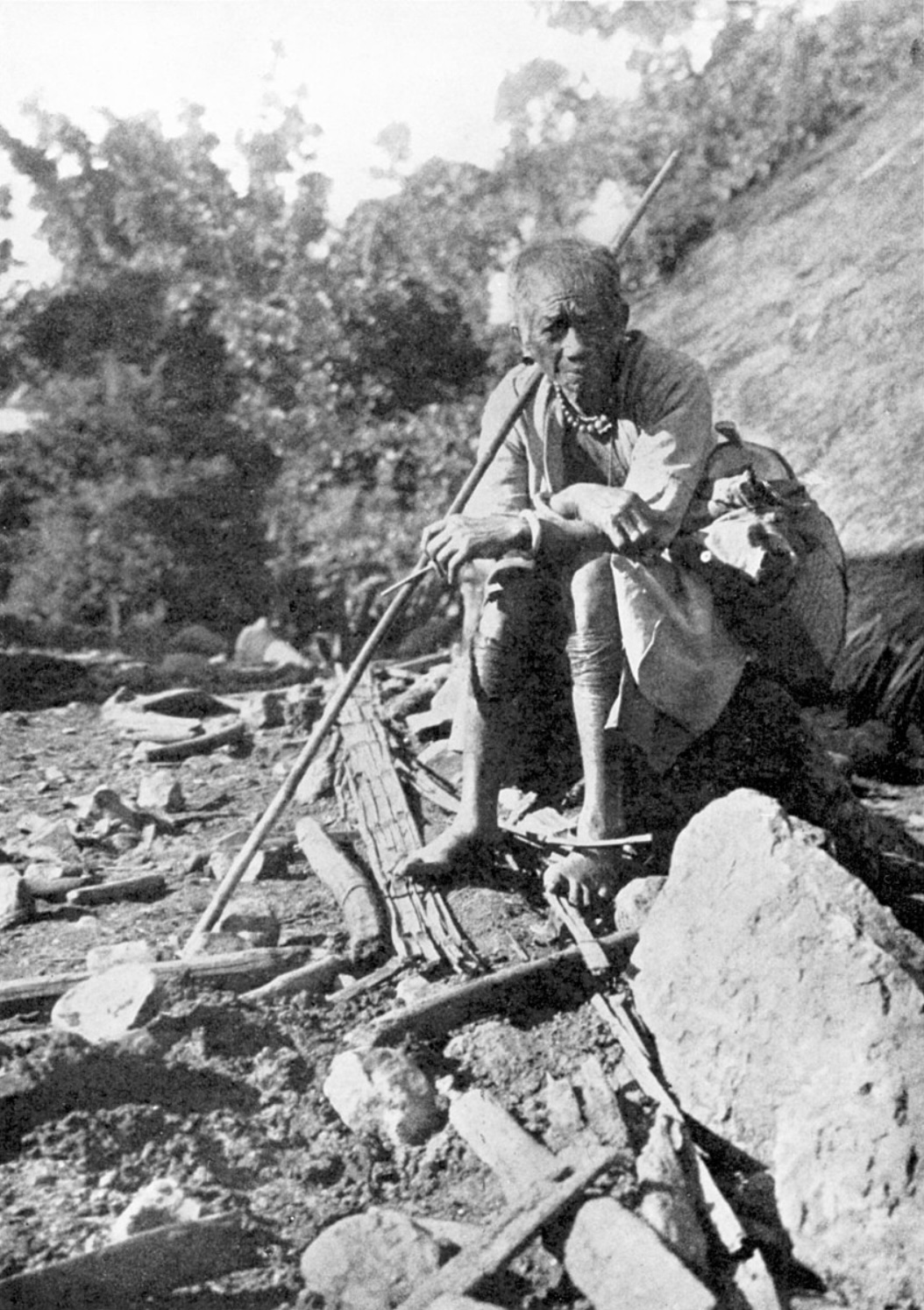

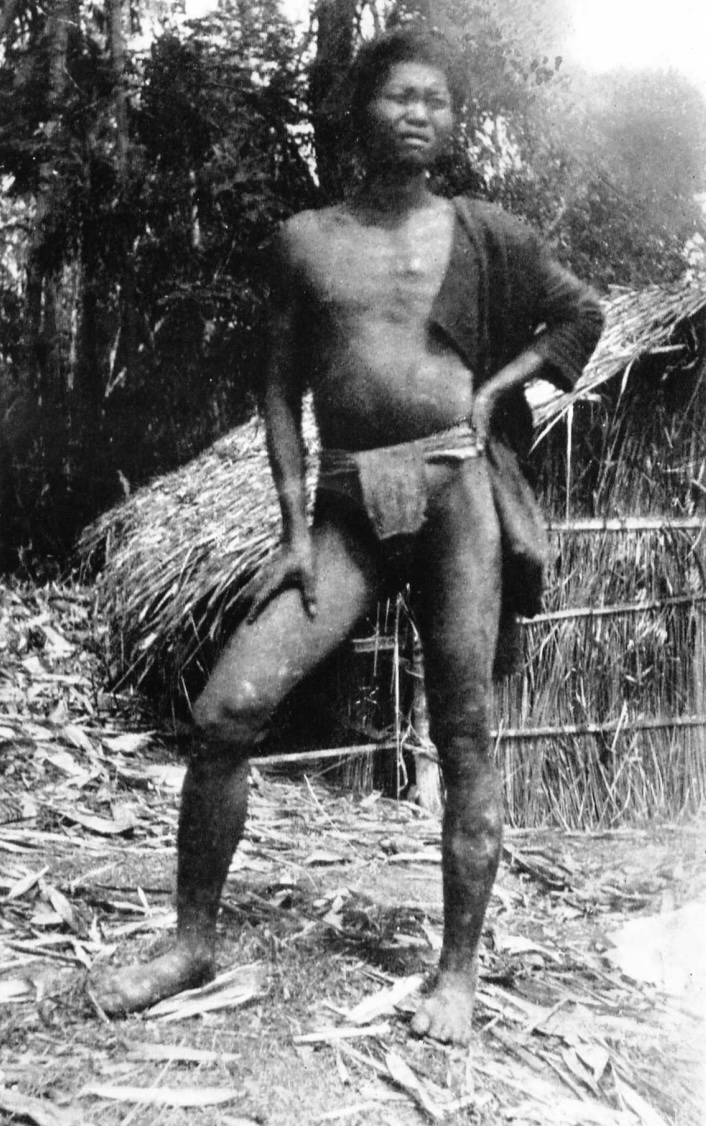

In his essay in Impressions of Burma, Scott introduced the Wa as “a quite fascinating problem”. Prior to his expedition, they were believed to be cannibals. This he had disproved but, even in the early years of the twentieth century, they were known to be active head-hunters. (In 1908, we are told, they decapitated eighty-seven Chinese, besides others.) Otherwise, they grew enormous amounts of poppy, from which they used the opium to barter with enterprising Chinamen “for salt, a few guns, and iron to make head-chopping knives”.

In particular, Scott was fascinated by the creation myth of these fearsome people:

The primeval Wa, the first of the race, were called Ya Htawm and Ya Htai. As tadpoles they spent their earlier years in the lake at Nawnghkeo, an uninviting-looking oval lake at the top of a mountain seven thousand feet high, not far from Mong Hka …

When the Wa became frogs they moved to a place called Nam Tao where, in the progress of time, they grew to be ogres, and two of them set up house together in a cave called Pakkate … From this cave they made sallies in all directions to get food, and at first were content with the flesh of wild pigs, deer, goats and cattle. As long as this was their diet, they had no young. But all ogres (Hpi Hpai) in the end come to eat human beings; it is their most distinguishing characteristic, after having red eyes and casting no shadows …

One day Ya Htawm and Ya Htai went farther afield than usual and came to a country where men were living. They caught one and ate him, and carried off his head to the Pakkate cave; after this they had quite a family of ogrelets, and singularly enough all of these were in ordinary human form. This pleased the parents so much that they set the original human skull on a post and worshipped it. [30]

He then draws a distinction between different categories of Wa skull-collector. According to the Chinese, who knew them best, at the apex of the pyramid was the “real” Wild Wa, who took any head that came his way, albeit with a preference for those of strangers and wanderers. Next there came those Wa, who took no heads without some justification, and who focused their attention on thieves and reivers. After these, there came those who only bought heads. They were looked upon as being “on the way to good livelihood”, but they were unconcerned by matters of provenance. If the seller did not come by his skull honestly, that was his concern, as he took the risk. Last of all, there came those Wa who were satisfied with the skulls of wild animals such as bear, panther, or sambar.

Unfortunately, material prosperity bore an inverse relation to civilisation. The Agung-pyat-Lawa, as the Burmese called the head-harriers in the first category, had the most substantial villages, the greatest numbers of live-stock, the most ornaments, and the least clothes. They also had the highest opinion of themselves. The Tame Wa, by contrast, lived in hovels and, if they were in possession of a small field, it often came without a cow. Instead of ornaments they wore clothes, but this made them more filthy, for while dirt is apt, eventually, to flake off a person’s skin, with rain or heat it works its way into clothes and ultimately becomes “very offensive”. [31]

Scott is quick to point out that the Wa never used the heads of their fellow villagers – the basic elements of political economy prevented that. Further, it required a matter of very urgent necessity, such as a severe drought or pestilence, for the taking of heads from a nearby village to be sanctioned. Indeed, to behead someone even from the same range of hills was looked upon as “unneighbourly and slothful”. For the best results were expected to follow if the spirit of the dead man came from far away, and he was unfamiliar with the territory into which he was removed. In this case, he was less likely to leave his bodily remains and wander away. And this was a key point, for the idea was that such spirits, which were always truculent, resented others trespassing on their territory, and so protected the village in which they found themselves by keeping them at bay.

Rather surprisingly, Scott’s researches led him to conclude that the neighbours of the Was’ victims did not usually harbour resentment against their “sportsmen”. To us, their attitude might most obviously be explained by fear. But, to Scott, this was not the main cause. Rather it was because the practice was a matter of religious observance, and because the Wa never ventured beyond their territory when collecting their heads. If someone else was careless enough to be caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, then that, in a certain sense, was his look-out. [32]

As to the manner in which their heads were displayed:

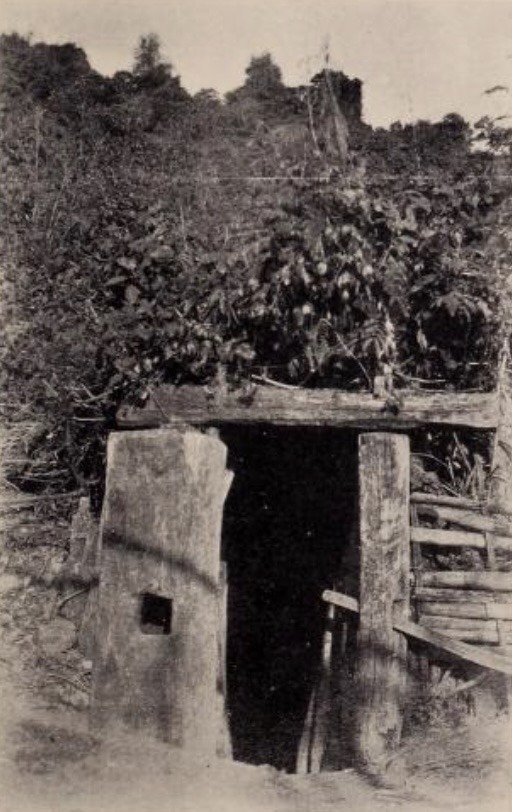

The general character was always the same. There is a row of stout posts about three and a half to four feet high and from five to six feet apart. In each of these, roughly about a foot from the top, a triangular niche is cut with a flat ledge at the bottom, on which the skull is placed. The line of skulls is always on one side only and the style of setting them up seems to be rather a matter of local idea than the following of a fixed rule. The commonest form is to mount the skull on the ledge facing the road, so that the whole of it can be seen, but perhaps because the post is not always stout enough, the skull is inserted from behind, so that only a grinning line of teeth is seen through a slit, with more or less jaw and frontal bones. This may be done with the idea of giving better protection from the weather. Undoubtedly the fashion makes the whole thing, to our eyes, more uncanny.

There was an official head-cutting season, which ran through March and April, because a minimum of one new head per year was needed, if the failure of the crop was to be avoided. But the head gatherers went about their task in a dilettante way, taking their opportunity whenever it was offered to them. Clearly, the more heads they returned with, the better the protection might be, but the possibility of a head “surplus” also introduced the concept of a market:

The skulls of the unwarlike Lem Shans are the cheapest. They can sometimes be had for a couple of rupees. The next nearest, both in the hills and in the price, are the La’hu, but they are not the sort of people to be taken without a fight, and it might be that there would be few available, were it not for their sporting habits, which take them away to jungly places in small parties or even singly …

He explained that no effort at marketing was made to tempt more civilised purchasers. Rather, the professionals served them out of “contemptuous pity”, and without necessarily demanding coin. It would be a brave man, Scott suggested, who had the nerve to bargain with the Wa-Lon. On the other hand, the professionals had a very clear idea of which classes of heads were the most valuable:

… a Chinaman’s will fetch 30 rupees, a Burman’s – they are very scarce now – 50, while a novelty in the shape of an entire stranger’s, such as an Englishman’s, would imply a free fight in all the hills for its possession. [33]

Most villages counted their heads by tens or twenties, but Sung Ramang’s village had on display many more. It was therefore with some trepidation that Mr. and Mrs. Scott approached it:

The cautious approach was, however, quite unnecessary. When the village was entered, all the men were found drunk in the police-court sense; that is to say, they were not able to lie on the ground without holding on.

Scott took the opportunity to pitch camp on a piece of open ground. Given the condition of the villagers, he did not consider it necessary even to station pickets. Then, shortly after sunset, the village was filled with the sound of shrieking. Everyone was put instantly on the alert, fearing some sort of attack, but they were quickly reassured by their missionary-guide, who explained, “These are the shouts of them that triumph, rather like the hallelujahs of a revival meeting”:

The head which the Wa had taken, and were celebrating in their own way, was hung in a basket in a leafy tree, and the noise was caused by the women toasting it. Soon after all sound ceased. Toast drinking goes soon to the head.

Elsewhere, Scott explains that a new head was never put up on its post “fresh”. It was only the cleaned skull that placed at the entrance to the village; either it was wrapped up in grass and leaves and hung in a basket in a dark corner to ripen and bleach or, occasionally, it was hoisted in its rattan cage to the top of a tall bamboo placed in the village centre, in “a savour of ostentation”. As to the subsequent ceremonial, he says only the Wa had ever seen it. He speculates that it involved much slaughtering of buffaloes, much chanting of spells and, above all, much drinking of spirits. “The service throughout seems to be corybantic rather than devotional”, he writes, “[which] no doubt accounts for the meagreness of the information on the subject”. [34]

Unlike the chieftains of the Shan, Sung Ramang himself proved very elusive. This made diplomacy difficult. As he arrived at the village entrance, Scott says a man who said he was chief appeared and asked his party to stay away. Yet he was not the chief. Nor were five others who, at one time or another, were presented as such:

We walked all over the village; we sat for some time in the Chief’s house, and almost certainly spoke with him without a knowledge of which in the crowd he was. Sung Ramang is said to have derived his good fortune from the possession of a nine-tailed dog. When even an allusion to this notable animal failed to arouse the pride and disclose the person of its owner, I gave up the attempt in despair. [35]

At Mong Hka, Scott became acquainted with an ecclesiastic known as Ta fu yè, who sent a band with gongs, shawms, tom-toms, cymbals and a drum to welcome him. Nominally a tributary of Sung Ramang, to whom he sent offerings of bullocks, pigs, opium and liquor annually, he had also recently been visited by the Chinese, who had taken away his seal and made him pay tribute by force majeure. This ta fu yè was not only chief of the village but was also, if not actually himself the object of worship, at any rate the chief ministrant during its festivities, and he lived in a house, the precincts of which reminded Scott of the courts leading to a Confucian temple. One of these courts had, at its centre, a rudely squared block of stone which served as an altar. The presence around the village of a number of similar small shrines, which went by the name “fu-fang”, or “Buddhist shrine” in Chinese, and the apparent concentration of temporal and religious power in the hands of the ta fu yè, were strongly suggestive to Scott of the lamas of the monasteries of Tibet. And yet this lama, if that was, in any way, an appropriate description of him, lived in a state of terror:

He extended his suspicions even to my private Chinese teacher, and invited me to a secluded interview in an apartment, half lumber-room, half oratory, in the centre of his house, where, far from the light of day, he confided to me his hatred of the Chinese, his terror of the Was, and his desire to become a British subject. I told him I had no authority to make settlements until the boundary between the possessions of Britain and China had been determined. He said that unless there was an early settlement his position would become intolerable, and he and his people would have to migrate. [36]

In this first tour of the Wa, it is remarkable how much Scott achieved with so little fighting. In part, this reflected his good humour and his fine diplomatic skills. However, it was also a measure of his respect for the people.

Despite their head-hunting foible, he realised that the Wa were not bad neighbours, at least in the sense that, unlike the Kachins and the Kwi, they were not thieves, and they did not raid and burn villages. The cutting off of heads inevitably “tempered esteem”, and the amount that they drank and the little that they washed no doubt caused some disapproval, but they had other attributes that commanded admiration. They were extraordinarily hard-working cultivators (the fields in which they grew their rice were frequently thousands of feet below the hilltops on which they lived), and they were skilled at transporting water over long distances using bamboo. Living near water was considered unhealthy, because of the risk of fever, and considerable zigzagging was required, when an aqueduct was bringing water from high up, if the water was not to enter a village with excessive force. The Wa were also adept at crossing wide rivers with bridges cleverly constructed using bamboo and rattan.

It seemingly took only some of the gloss of Scott’s opinion that the water was used chiefly for making liquor, and that the principal function of the bridges was “to avoid the involuntary washing of anything above mid-thigh”.

Returning to the habit for which the Wa are best known, however, Scott also saw fit to draw favourable comparisons with others who were similarly inclined:

The cutting off of heads is a sort of sacrificial act, not an exhibition of ferocity or wanton, depraved habit. It is really done for the general good: to protect their homesteads and to stop the pressure which has driven them back so far from lands they used to hold. … Their skull avenues, no less than their outrageous hill-ranges, are a warning to land-snatchers that they are not going to stand it any longer. It is not at all a personal matter. No Wa makes a collection of skulls as some people do of postage stamps, match-box labels or pressed ferns. The Wa does it for the common good. He is not like the Papuan, who cuts off heads for exercise, and eats parts of his victims if there are not too many of them. Nor is he like the Dyaks of the interior of Borneo, among whom no man can get a girl to marry him unless he has killed his man, and, to prove the point, for the Dyak maidens seem to be tyrannical and not squeamish, can produce the head as one might present a posy of violets or a spray of orchids. [37]

For all that, it is certainly the case that Scott’s two subsequent visits to the Wa territory were much less peaceful than his first. (Sadly, they were made without Dora, who died of malaria in 1896. Scott was devastated, and it is perhaps no coincidence that he appears less attractive from this point.) [38]

In early 1897, he intervened in Manglun, where Naw Hkam U, the nephew of the sawbwa at nearby Lon Long, was building a coalition with other Wa chiefs and the Chinese, as a defence against British encroachment. Having in vain tried to trace the sawbwa, who fled at his approach, Scott discovered some incriminating letters in his house:

From the Sawbwa of Mong Lem to Naw Hkam U dated 12 October 1896:

The Chinese authorities have sent orders to Mong Lem and Loi Lon directing us to find out about the coming of the British into our country and the Wa states. You are to find out if they are coming or not, and if they have come, you must let our Chinese masters know without delay how far they have advanced, how they treat you, and what is their object in coming, and whether they come peaceably.

From Ngek Lek and Sun Long to Naw Hkam U dated 12th October 1896:

We must resist the British no matter by what route they come. If they come through Ma-tet we will resist them. If they come through Loi Lon resist them and make a good stand; we will send reinforcements … Fight for our common cause. If you do not fight, you would be leaving us and joining the British and Mang Lon. If we do not fight, then we should be guilty of forsaking you and joining the British and Mang Lon. [39]

Up until this point, Scott had been confident the sawbwa could be persuaded to remain loyal, but now he was convinced a coalition of the Wa was being formed against British authority:

I therefore decided to burn the place … It was too formidable as a position to risk having to take a second time. I had not time to go on indefinitely with purely persuasive or diplomatic measures. All hope of getting in Naw Hkam U seemed to have gone. The citadel was full of rice and pigs and fowls. Our followers had been able to get nothing since our arrival and the sepoys’ rations were running short. I therefore gave over the place to plunder for three hours and then burnt it … Up to this moment we had done nothing that could be called an act of war; we had done nothing that could reasonably have been called threatening. No doubt the burning was the cause of subsequent hostilities, but I cannot see that under the circumstances any other course was open to me. [40]

Although Scott claimed the fighting that followed was as distasteful to him as to anyone, he later admitted that he had been tempted to it by hopes of securing a “gold tract” (subsequently called a “deplorable illusion”). He was also forced to concede that his campaign met with failure. At first, Scott seemed to think that firing these villages was a relatively small matter, as they took just a few days to rebuild, but he soon appreciated that his idea of putting the uncle, Naw Hseng, in the place of Naw Hkam U was a fruitless exercise. Naw Hseng was willing to act as a stooge to the British, but he had little else to recommend him. Scott later called him a weak, cowardly fool, who had no qualifications for British support but one, “which was all important”. [41]

The other chiefs coalesced around Nam Hkam U. They resisted and other villages were burned. An adventure in Ma Tet resulted in a repulse and, before long, Naw Kham U had himself reinstated anyway.

For his efforts, Scott received criticism from the Lieutenant Governor of Burma, who judged they were contrary to his instructions and produced results that he particularly wished to avoid. Fortunately for Scott, he was overruled by the government at Simla, although British officers were told in future to keep away, with effects – in terms of British prestige – that Scott was soon to deprecate:

February 13th, 1897. The whole situation is distinctly unpleasant. It is somewhat aggravatingly clear that the Muhso politely hint that we are afraid of the Chinamen. Many, at any rate of the Wa, are convinced that we are afraid of them … They utilize events cleverly, saying that we come only once a year, if so often, and that then, if we do not occupy ourselves in burning villages, we rush through the country asking what the Chinese have been doing. The inference is apparently readily drawn by the ingenious savages of these parts. [42]

There was no personal disgrace, however, and Scott remained in sufficiently good odour to serve on the Burma-China Boundary Commission in 1898-9 and 1899-00. The last season involved a final mission to Wa country, during which two wayward British officers lost their heads:

After a fortnight’s work two Chinese soldiers proved that they were rude and licentious, and General Liu, the Chinese Commissioner, who ordinarily was amicable enough, but could be autocratic, decided that disorderliness of this sort could not be overlooked. Therefore, he promptly had the two culprits beheaded and their heads were set upon the posts of the Mong Hka gate … as a protection for the Shans of the market town against the turbulent and overbearing Wa of a high ridge that overlooks it.

Two officers from the British camp, which was only about a couple of miles away, rather unwisely took an after-tiffin stroll out there to see the village and the heads. Unfortunately, it was bazaar day, and the place was crowded with wild men from the Wa hill-sides excited at the sight of gory heads and with the liquor they had looted from the stalls. They came across the Englishmen, who were quite unarmed, and in fact they had only one swagger-stick between them. … The Wa followed them in a wild yelling crowd, growing more excited as the officers, Surgeon-Major Kiddle and a young political assistant named Sutherland, quickened their pace. They were surrounded, and their heads hacked off half a mile or so from the gate …

According to Scott, the punishment meted out to the Wa was not one they were ever likely to forget. General Liu and he joined forces and sent three avenging parties scrambling up a mountain spur as high as 2,500 feet. The Wa fought valiantly, and a Gurkha was shot in the throat at point-blank range through the village fence but, after that, its inhabitants took to their heels. Everything in the village, including its spirit house, war-drum, liquor store and granary, were put to the torch.