The Early Career of Lord Camelford

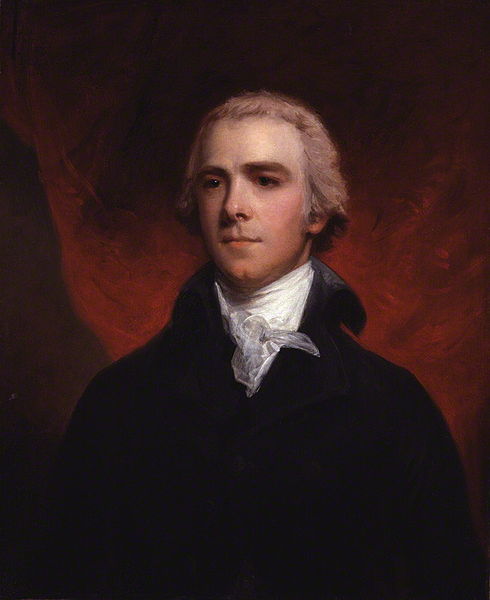

The second Lord Camelford was born Thomas Pitt on 19 February 1775. His family had first come to prominence through the career of Thomas “Diamond” Pitt, governor of Fort St. George at Madras (1698-1709). The cornerstone of its wealth was the profit Pitt made on a 410-carat rough diamond which he acquired in 1701 for £20,400 and smuggled to England in his eldest son’s shoe. As rumours circulated that Pitt had obtained the diamond fraudulently, Alexander Pope wrote,

Asleep and naked as an Indian lay,

An honest factor stole a gem away;

He pledged it to the knight, the knight had wit,

So kept the diamond, and the rogue was bit.

Some scruple rose, but he eased his thought,

“I’ll now give sixpence where I gave a groat;

Where once I went to church, I’ll now go twice –

And am so clear, too, of all other vice”.

From the diamond, several stones were cut, including a 141-carat brilliant, known as “Le Regent”, which was sold to Philippe II, Duke of Orleans. It became one of the crown jewels of France. Other stones were sold to Peter the Great of Russia. For “Le Regent” alone, “Diamond” Pitt netted the princely sum of £135,000. [1]

With the proceeds, Pitt bought the beautiful estate of Boconnoc near Lostwithiel, in Cornwall, and settled down to the life of a well-heeled country squire. The family prospered. His grandson, William, rose – as Pitt “The Elder” – to become prime minister during the Seven Years’ War. As such, William raised his nephew (and thus Diamond Pitt’s great grandson) to the title of first Lord Camelford and Baron Boconnoc in 1784. [2]

Our Thomas’s mother was Anne Wilkinson, daughter of a rich London merchant, Pinckey Wilkinson, whose sister eloped with an impecunious Guards captain, John Smith, in 1760. In 1764, she gave birth to a son, later Admiral Sir Sidney Smith, the hero of Acre. Sidney’s glittering career began when Thomas was still young. He obtained his first command after serving with Rodney at the Battle of the Saintes in 1781, and he was to have a strong influence on his cousin’s character and career.

Thomas’s early childhood was not a happy one. His father suffered from depression, “anxiety of mind” and epileptic fits, although these ceased in middle age. His parents were otherwise formal and forbidding, when they were around, and he was left at Boconnoc under the care of a rather unsatisfactory clergyman-tutor.

Thus as with ripening years his mind matured

His lofty spirit burn’d without control,

And self directed no restraints endured

While passion oft time shook his fervid soul. [3]

At the age of eleven, Thomas was sent to a school in Neuchatel to “continue” his education. Shortly after his arrival he wrote,

There is only one Englishman in the house of about 17 or 18 years old who cannot be my companion as you may conceive. But I like him very well he is not in the least Proud as I should have expected. As to Mr Meuron I have a little more to do with him than I should wish at Present; Because as the Masters cannot comme till the Beginning of the Month he gives me all My lessons. I think he is a very good natured man but he has the Most detestable manner you ever saw he never seems contented with anything; & you know there is nothing I hate more. [4]

It was a difficult start, but Henri de Meuron proved to be a sympathetic teacher and Thomas was soon to revise his opinion of him. In time, he was to look back on his days at Neuchatel with fondness; they certainly contrasted favourably with the sterner discipline of Charterhouse, where he was sent in 1789, aged fourteen. There, he stood it only nine days before running away.

In September of the same year he persuaded his father to allow him to enrol in the Navy. His first berth was aboard His Majesty’s sloop Guardian, whose captain, Edward Riou, was charged with the task of taking a cargo of provisions, twenty-five convicts and a number of superintendents to Port Jackson, New South Wales. It was to prove a hazardous voyage.

All went well until after the Guardian passed Cape Town. On Christmas Eve 1789, twelve days into the second leg of the voyage, a large iceberg was sighted. The sea was calm and Riou sent his boats over to it to collect broken pieces of ice for water, which was being depleted by the plants and animals aboard. The operation was successful, but then a fog descended. Lookouts were posted to the bows and rigging, and the ship edged forward. Then, at eight o’clock, when the worst of the danger seemed to have passed, there was a wrenching crash. The Guardian had struck. Her rudder was smashed, and a hole had been torn in her side.

The ship pulled free, but the water in the hold gained on the pumps. By midnight, it was six feet deep, and outside it was blowing a strong gale. Guns, anchors, cattle and a variety of other impedimenta were cast overboard. At dawn on Christmas morning, a fothering sail was passed over the side to stem the ingress of the sea and some gains were made, but then the sail split and the level of water began to rise once more.

By five o’clock, the water in the hold was four feet deep. At six on the morning of 26 December, seven, and gaining at the rate of a foot every half hour. The weather was “uncommonly piercing”, the ship was rolling violently, and water was pouring in around the rudder case. The Guardian started to settle at the stern. The boats were prepared, but there were insufficient places for the convicts and crew. 259 people were put on board and they rowed away, most never to be seen again. Sixty-two, including twenty-one convicts and Thomas Pitt, were left behind.

The Guardian was now awash, with sixteen feet of water below decks. At this desperate juncture, a knocking noise was brought to Riou’s attention. A number of barrels had broken free and were floating in the hold, trapped beneath the gundeck. Realizing they were providing extra buoyancy, Riou ordered the gundeck hatches sealed and caulked, and had another sail passed under the hull.

For two months, Riou and his skeleton crew now sailed the shattered remains of the Guardian four hundred leagues to the Cape. Eventually, on 21 February 1790, they were sighted by whalers and escorted to safety at Saldhana Bay. It was a most fortunate escape. [5]

One might have thought the experience would have been enough to persuade Thomas to pursue an alternative career. No such thing. Instead, it proved an inspiration for further exploits and, before long – aided by some string-pulling by William Grenville (another of the extended Pitt clan, then Home Secretary) – he was enrolled in the complement of HMS Discovery, captain George Vancouver, and headed for the west coast of North America.

By mid-1791, he was back off the Cape (the Discovery sailed from West to East) and in sufficiently good odour with his captain that he was promoted to master’s mate, the first step on the ladder to lieutenant. However, Vancouver proved to be a hard taskmaster, “verry passionate” and little able to “put a favourable construction on any part of the follies of youth.” There is evidence that most, if not all, in the midshipmen’s mess grew to dislike him. The heir to Boconnoc may have been singled out for harsher treatment. He was flogged three times on the voyage, and there is no doubt that, for him, the situation became intolerable. The bad blood between Vancouver and his midshipman grew increasingly intense until, on 7 February 1794, Thomas was discharged and placed on board the supply ship Daedalus for Port Jackson. [6]

There he learned that his father had died in the previous year and that he was now the second Lord Camelford. Grenville had become Foreign Secretary and the new peer’s brother-in-law (he married Thomas’s sister Anne in 1792.) He had heard of Thomas’s quarrels with Vancouver and was anxious to bring him home. However, Camelford, conscious of the damage that Vancouver’s reports might do for his reputation, decided the best way to put the record straight would be through meretricious service under another commander. One way or the other (it is not clear quite how), he made his way to Malacca, where he engineered a posting on the frigate HMS Resistance, under captain Edward Pakenham. [7]

By the start of 1795, he was an acting lieutenant and Pakenham was describing him to the Admiralty as “a most promising Officer, every way qualified for Promotion.” It was a successful cruise lasting nearly a year, but it was served on a station that offered little scope for further advancement. In November, advised by Pakenham that he might do better to look elsewhere, Camelford bore the Resistance farewell, and travelled up the coast from Malacca to Penang, where he bought his “country ship”, the Union, for the journey home via Bombay, the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. As we know, he only got as far as the approaches to Trincomalee, where the Union disintegrated.

It is time to return to the Scots professor we left earlier preparing to eat his supper in a Ceylonese paddy field.

Hugh Cleghorn, the Comte de Meuron and the Conquest of Dutch Ceylon

The source of the Cleghorn family’s fortunes was “The Fellowship and Society of Ale and Beer Brewers of the Burgh of Edinburgh”, actually the first commercial company to be incorporated in Scotland (in 1598). But while Hugh’s grandmother, Jean, and her second son, John, were still involved in the running of the business at the time of his birth, on 21st March 1752, it was “academical blood”, as Hugh himself put it, that ran in the family’s veins.

Hugh’s great grandfather had been Principal of Edinburgh University. There, both his grandfather and his uncle William served as Professors of Moral Philosophy. His uncle on his mother’s side was a Professor of Greek and he had a cousin who was Professor of Mathematics at Aberdeen.

Uncle William – whom Hugh seems to have greatly admired – was familiar with a number of the members of the Scottish Enlightenment; the architect Robert Adam, the philosopher and historian Adam Ferguson, the poet William Wilkie among them. He gained the chair of Moral Philosophy, in 1745, in competition with David Hume.

It was Hugh’s good fortune, therefore, to spend his formative years in an environment of tremendous intellectual vibrancy. Little surprise, then, that he too sought a teaching career, which began in earnest on 1 April 1773, when he was enrolled at Professor of Civil History at the University of St. Andrews.

The problem was that, compared with Edinburgh, St. Andrews was very quiet. Later, Cleghorn was reminded of it on a visit to Ferrara: “There was scarce a person walking the streets … and the grass was growing under our feet … it resembles St. Andrews though on a much larger scale.” Cleghorn was diligent enough, no doubt about it but, after a time, the seclusion of his university was unable to provide him with the stimulus he needed.

Indeed, during the last years of his St. Andrews professorship (1788-1792), Cleghorn was noticeable only by his absence. In May 1788, he obtained permission to escort Alexander, tenth Earl of Home, on a travelling tour of Europe. Leaving his wife behind to look after their seven children, he travelled to Paris – this at the time of the recall of Necker and the debates over the Estates General. Switzerland followed and then, after an extension had been granted to his sabbatical, Rome, Sicily and Naples.

By the time the tour was over, in October 1790, there was no going back to the dull world of academia. As the editor of the Cleghorn Papers puts it: “Was he expected to set examination papers on the revolt of the plebs and the First and Second Punic Wars seemingly utterly oblivious to the fact that the plebs were in revolt in virtually every country on the Continent?” He was watching civil history in the making, and his mind was increasingly exercised by the ways in which he might personally further his country’s interests. [8]

Thus, instead of returning to St. Andrews – as he was being bidden to do by an increasingly fractious University Senate – Cleghorn spent much of the next two years in London casting about for a way in which he might join government service.

In November 1790, he presented a paper to the foreign secretary, the Duke of Leeds, on the advantages that would accrue to Britain, if she supplanted France as the ally of Switzerland. To do so, he argued, would open fresh sources of capital to finance the war, and would create the option of striking a blow at France on that part of the frontier they could least easily defend. Moreover, he wrote,

… seventeen Marching Regiments of Swiss and several Regiments of Swiss Guards are at present in the service of Foreign powers [and] all would prefer, on Account of the Superiority of the pay, the British Foreign Service, to that of any other power.

With the report went the suggestion that a knowledgeable agent might be sent to Switzerland by the government to see what might be achieved. “I have no claims from personal pretensions to employment,” Cleghorn added, “yet should I be honoured with any commission … I am confident that, sent to that country, I could be of use to my own.” Alas, in 1791, Leeds was replaced by Camelford’s cousin Lord Grenville, and – as was the way with minsters such as he – the role went to one of Grenville’s friends.

However, the idea struck a chord with Henry Dundas, Treasurer to the Admiralty, who had also just replaced Grenville as Home Secretary. Encouraged by him, in November 1791, Cleghorn wrote again to St. Andrews soliciting “a continuance of the indulgence which [you] have hitherto had the goodness to grant me.” A refinement of his earlier idea was gestating in his mind.

In the autumn of that year, Charles-Daniel, Comte de Meuron arrived in England. Cleghorn recalled that, when in Neuchâtel on his Grand Tour, he had struck a friendship with this man, a relative of the Henri who, at the time, had been busy tutoring the young Thomas Pitt. The Count was the “Colonel Propriétaire” of a Swiss infantry regiment in the pay of the Dutch East India Company.

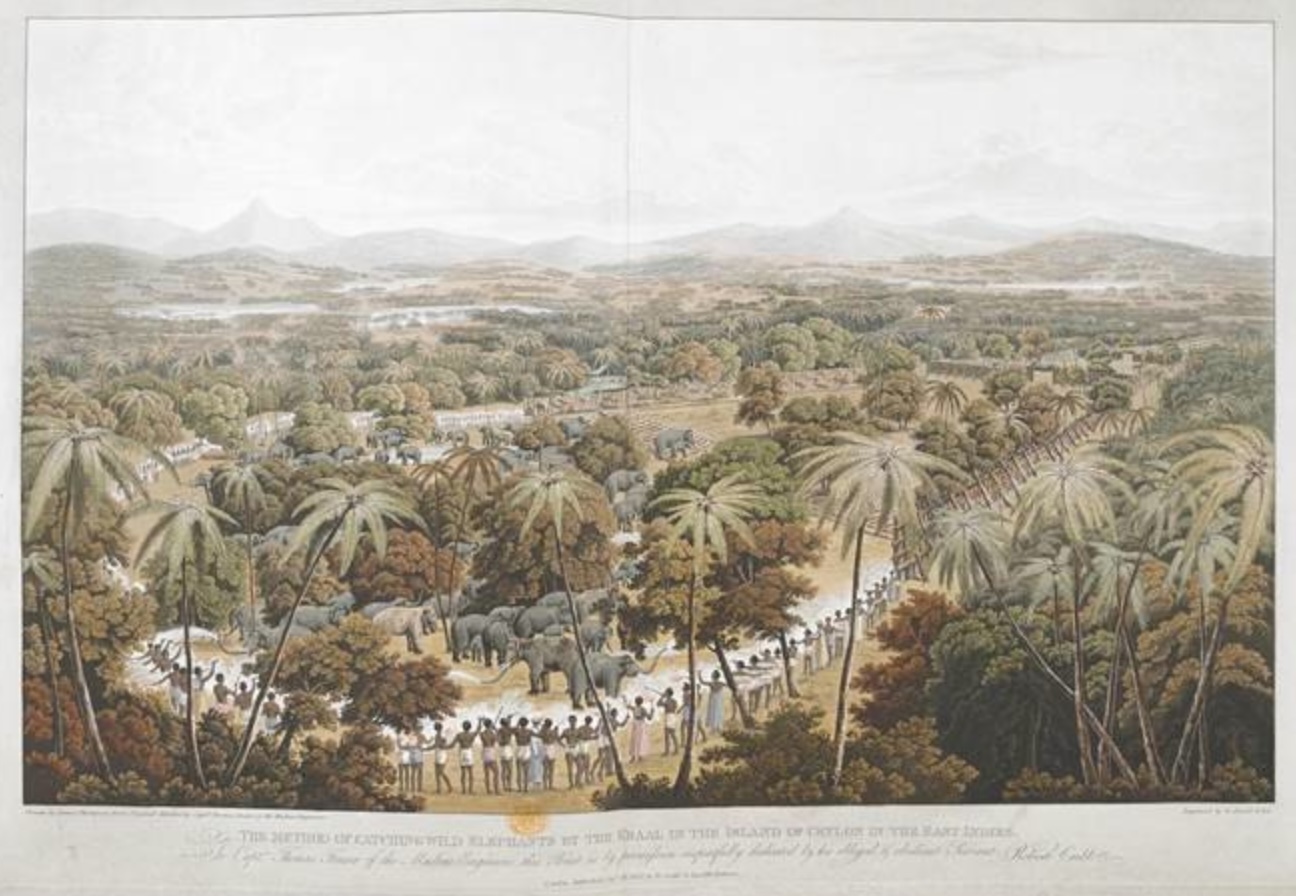

From 1783, the Regiment de Meuron had been serving the Dutch at the Cape, but the Dutch were poor payers and, in 1785, in an attempt to collect what was owed, an exasperated Count had returned to Europe leaving behind his brother, Pierre Frédéric, as “Colonel Commandant.” In 1788, the regiment was sent from the Cape to Ceylon and other Dutch bases in Asia. What, suggested Cleghorn to Dundas, if it could be induced to quit the Dutch and put itself at the disposal of England?

Evidently, in 1791, the Count was having similar thoughts of his own. At the time of his visit to London, he wrote to his friend the Countess Duhamel,

I must look for a way out of this oppression by one means or another. I can see a few possible ways of achieving my objectives, even though progress is still at a very early stage. You can well imagine how careful I have to be. [9]

At this juncture, the Revolutionary Wars had not started, and Britain was disinclined to make waves, but Cleghorn’s ideas nevertheless served to raise him in Dundas’ estimation. In 1792, the Home Secretary wrote to St. Andrews to obtain another extension to Cleghorn’s leave of absence and sent him on what seems to have been an intelligence mission to Europe. (There are few clues as to his precise activities.) Then, at the end of January 1793, Cleghorn was formally added to the government’s payroll and submitted his resignation to the St. Andrews senate. [10]

For a period, he worked in what he called “the Precis office” of the Home office. Then, in January 1795, the French invaded Holland and established the Batavian Republic. The Stadtholder, William V, fled to London and there, on 7th February, he issued a directive (the so-called “Kew Letter”) to the effect that all Dutch colonies and forces should be transferred to the British to prevent them “from being invaded by the French.” An assurance was given to him that Holland’s possessions would be returned to her upon her liberation from France, but there nevertheless remained a risk that disaffected parties overseas would instead join the French side and thereby threaten Britain’s eastern interests. [11]

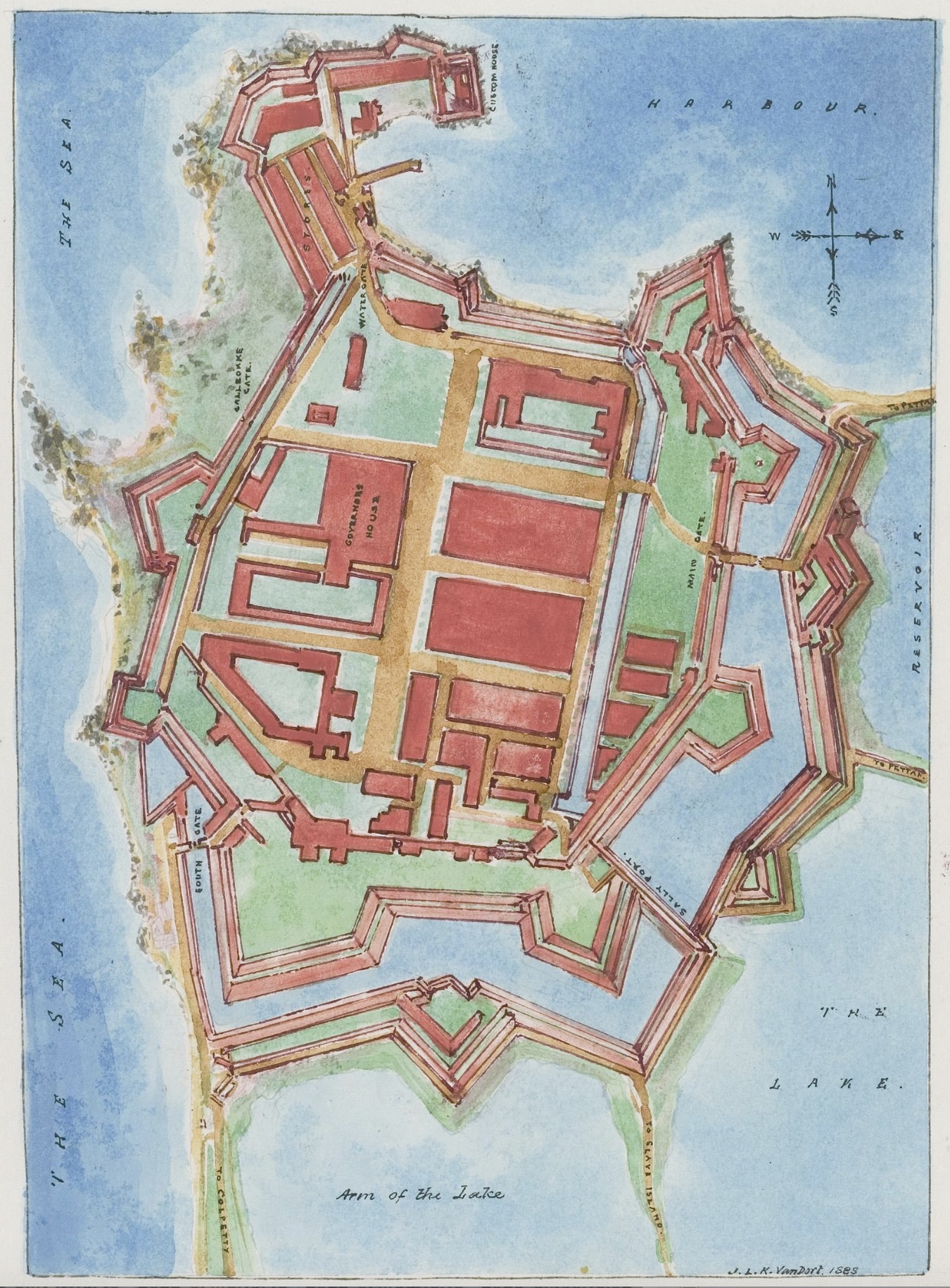

Ever since the Seven Years’ War Britain had been conscious of the vulnerability of the Coromandel coast to French attack. It possessed no natural harbours and was exposed to the north-east monsoon. Ceylon provided the only refuge nearby that was protected throughout the year. Accordingly, on 7 July, Lord Hobart, responding to a notice from London authorising him, “if it should appear consistent with the safety of our Possessions” to use force to enforce the Stadtholder’s edict, decided to send an expedition to Trincomalee under Colonel James Stuart “for the purpose of securing that important place against any attempt on the part of the French.” On the same day, Major Patrick Agnew was sent to the Dutch Governor of Ceylon, John Gerard van Angelbeek, with a copy of the Stadtholder’s Letter and a demand that he should permit Britain to occupy Holland’s possessions in Ceylon until such time as a peace guaranteeing Dutch independence was concluded. In the event of even “the smallest delay”, the colony would be taken by force. [12]

In September 1795, some three weeks after the fall of Trincomalee, Robert Andrews was sent on a mission to the King of Kandy to obtain an alliance and assistance with the supply of provisions. A preliminary treaty was signed between them on 12 October and, on the strength of that, the king proceeded to co-operate with Britain’s troops. [13]

It was in this context that, on 25 February 1795, Dundas, now War Secretary, wrote to Cleghorn as follows:

I have submitted to HM’s consideration the papers which I received from you respecting the Regiment de Meuron now employed in the Island of Ceylon, and I have in consequence been directed to authorize you to proceed to Switzerland, where you are to open a negociation with Comte de Meuron for engaging the services of that regiment on the terms you have proposed …

If the Count should accede to the conditions you are directed to offer him, you will sign a capitulation to that effect and transmit it to me, and in order to obviate any difficulties which may arise in India in applying the services of the Regiment to the advantage of this country, under the circumstances which will naturally take place, I would have you endeavour to exert your influence with the Count to proceed to Ceylon himself and take command of the regiment for a short time …

Cleghorn was encouraged to accompany the Count and, if he refused to go, to travel himself and carry out the plan under the Count’s instructions.

In a second letter, Dundas added the following rider:

The importance of obtaining the services of the Regiment de Meuron in the present moment is such as to render it advisable that considerable sacrifice should be made rather than any disappointment should arise. And, if upon a communication with the Count de Meuron any serious difficulty should be felt in engaging his services, you are authorized to offer him a handsome Douceur to induce his acquiescence, but at the same time you will understand that no such concession is to be made until you shall find that your endeavours by every other means shall have failed.

The extent of this Douceur must depend upon the Count’s expectations … but, at any rate, you are restrained from exceeding the sum of £2,000 and in any engagement you may make for the payment thereof its discharge must be suspended until I shall be apprized how far the undertaking shall succeed, which of consequence cannot take place until his arrival in Ceylon.

Dundas also enclosed a letter of credit “on the Correspondents of the house of Sir Robert Herries & Co., authorizing you to draw upon them for the sum of £1,500 on that account” and a letter to the Government of Madras instructing them to offer him their every assistance. [14]

On 1 March 1795, having arranged for an allowance of £150 a year to be paid to the wife he was again leaving behind, Cleghorn sailed for Cuxhaven at the start of a five-year adventure.

In Hamburg, the British Resident helped him engage a Polish servant, Michael Mirowsky, who accompanied him all the way to India. Having crossed the Elbe “partly by water, partly by a sledge drawn on the ice and mostly on foot”, Cleghorn travelled to Neuchatel via Hannover. It was hard going. All Germany was in motion, with “nothing but soldiers to be seen in the cities and on the roads.” One day Cleghorn wrote,

I have been this day, twelve hours in a carriage and am now stopped for want of horses, tho’ I have in fact sown the roads with gold. I have crossed the great Prussian army consisting of 60,000 men going to Westphalia. Their artillery required fifteen days to march twenty-five miles; hundreds of their horses are lying dead on the road and I everywhere met their mangled carcases half devoured by wolves and ravens … [15]

He arrived at de Meuron’s summer residence, La Petite Rochette, on 25 March. Cleghorn used his best arguments to persuade le Comte to commit his troops, but it took a full five days to agree terms. Le Comte insisted he be granted the rank of Major General, that his brother be made Brigadier General, and that a Captain Bolle be permitted to travel with the party as the Major General’s aide-de-camp, at Britain’s expense. Cleghorn acceded to these demands, although he had not been authorized to do so, and signed.

There had been no need for a douceur, but de Meuron insisted on a loan of £4,000 to settle his debts before departure and then announced he preferred to travel to Egypt from Venice and not Leghorn, as had previously been agreed. (The arrangements for a frigate which had, by then, been specially laid on for the journey had to be cancelled.) It was with some relief, therefore, that Cleghorn learned, on his arrival in Venice on 5 May, that his extra concessions had been approved. [16]

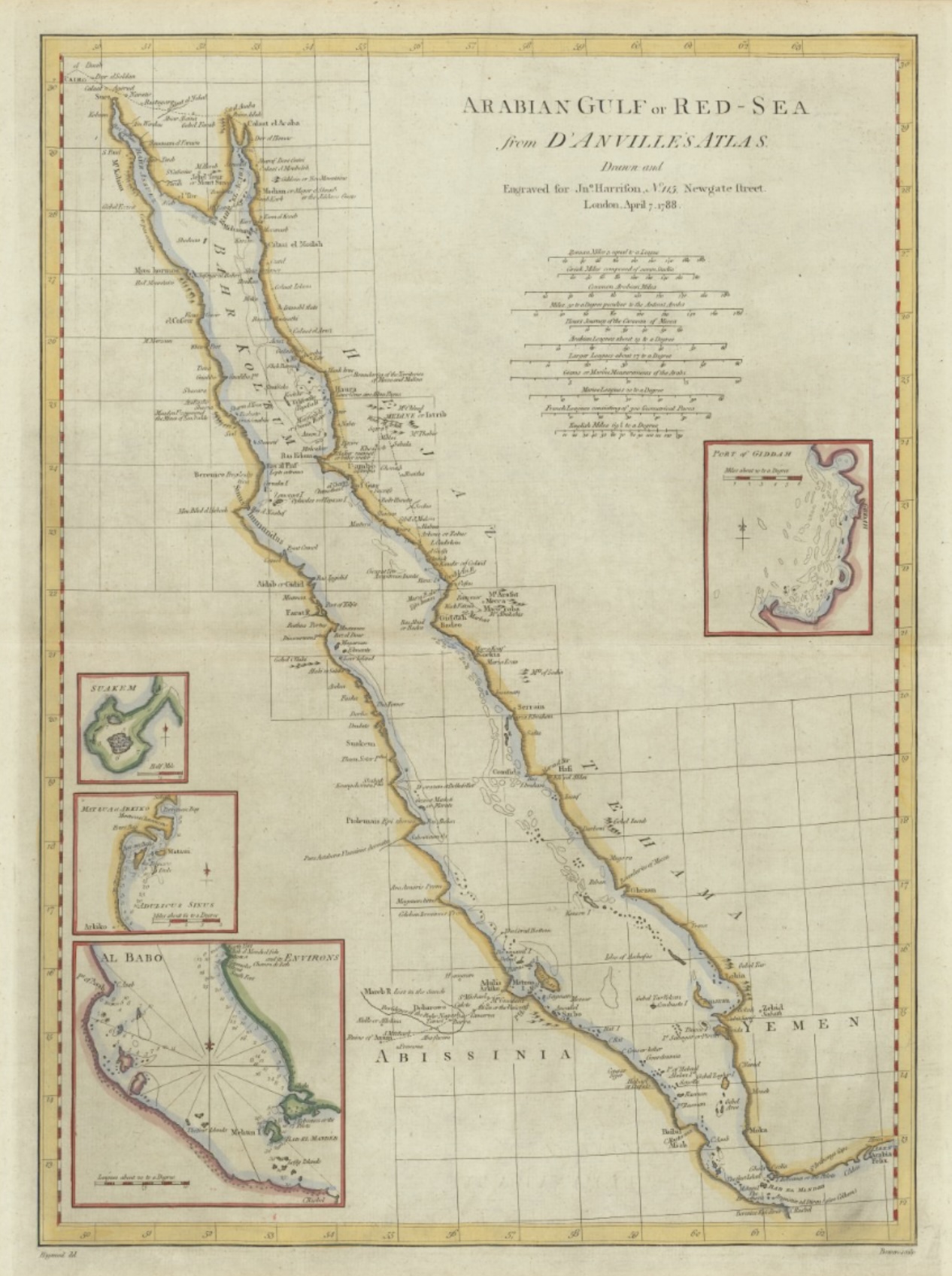

In Venice, de Meuron turned up with an extra “secretary”, Monsieur Choppin, whom he tried, but failed, to add to the British payroll, and on 18 May, they left for Cairo. The sea journey was uneventful, and in Cairo, they were conveniently put up at the residence of Mr. Baldwin, the British consul based in Alexandria. With the assistance of Mr. Rosetti, the Imperial Consul, they secured the services of an Arab escort for the journey to Suez, as well as of a Moorish vessel to take them down the Red Sea, no English ships being available.

According to Cleghorn, the Arab was “the most determined villain in these parts and connected with all the robbers in the Desert.” He added, “As they never attack those with whom they have a connection, we were assured he was the best protector we could find.”

The seventy-mile journey to Suez was accomplished at night in thirty-two hours. On arrival there, however, they discovered the vessel of the “mighty important” Turk who was to convey them to Jeddah “is not seventy tons, has no deck, and carries upwards of a hundred pilgrims.” They noticed its timbers were “slight and almost rotten” and “very imperfectly caulked.” There was no compass. They hired two cabins “if they deserve that name” at a cost of £300, even though they had to provide everything for themselves. Worse, the ship was not a quarter laden, and it was necessary to furnish a bribe if a delay of a fortnight was to be avoided.

As the time for departure approached, the scene threatened to mirror that on the Patna at the start of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim;

We are much distressed already to discover many musquittoes on board this new launched vessel. Our pilgrims are still on shore, where they have been lying like hogs in a stye, and the company which they will introduce already terrifies and distresses us. We have barricaded the gallery above our chambers, and as the passengers cannot approach us by accident, we are determined they shall not approach us by design.

When, on the evening of their departure, Cleghorn went up on deck to escape the smell of the bilges immediately under his cabin, he found “upwards of 220 people in a space not 50 feet long or 18 at its greatest breadth.” They were packed so tight that the mainsail could hardly be moved for the crowd that obstructed it, and Cleghorn felt himself “obliged to retire to my hole below.”

The journey proved to be as slow and as painful as these portents presaged. With the first stiff breeze, the sea began to break into their cabin and the “rotten” mainsail split; on 12 July, the Count was seized by an attack of the gravel; on 18 May, they had a near collision with a coral bank. “A few yards more and we should have been in pieces”, Cleghorn writes, before describing how they used the ship’s boat to bring their vessel about in an operation in which shrouds were carried away and the mast nearly broken.

On 22 July, at last, they reached Jambo (Yanbu), the port of Medina, where they suffered more delays because of the “extremely suspicious conduct of the vizier”, a “drunkard”, who demanded “the customary acknowledgements”, which the party was unable to supply. Cleghorn was sufficiently concerned that he dared not go ashore. Instead, he sent an open boat ahead to the senior captain of some English ships reported to be in Jeddah, asking him, if they did not arrive within eight days, to send out a party to collect his papers so that they might be conveyed to Lord Hobart in Madras.

By now, conditions on board were becoming insufferable:

We have now been seventeen days on board, and it will be about eight more before we get to Judda, and during that whole time our only exercise has been a change of posture from sitting to standing. To walk has been as impossible as to fly … Above we suffer from the numbers, noise and filth of the pilgrims, below the air is so confined that we can hardly breathe, and the stench of the bilge water has become intolerable … The nights are worse to us than the day, and we have got a blind female passenger from Jambo, who for at least five hours after sunset continues repeating and chanting without intermission passages from the Koran. She has taken her station immediately above our gallery and opposite to my mattrass.

On 1 August, as at last they approached Jeddah, they again suffered the peril of a near shipwreck. Cleghorn tells us the “[the ship’s] construction would have broken her in pieces on her first encounter against the rocks”, before adding that neither the Count nor Captain Bolle, nor M. Choppin, could swim:

There was no time to be lost. I made a packet of my most valuable papers, which I enclosed in a towel tightly tied up, and committed them to the care of [my servant] Hassan, who is an excellent swimmer, with orders to deliver it to Lord Hobart at Madras in case any accident befell me … I distributed my money to my friends and the servants, each of us having some rouleaus of Sequins buckled around our middle in a leathern cincture … We had prepared our firearms and had our cutlasses ready to keep off the passengers from our gallery and cabin.

Inevitably, there was only one lifeboat and, as all aboard were bound to attempt to get into it, Cleghorn and de Meuron “resolved not to make the trial.”

Fortunately, against the odds, the anchor held and, eventually, the vessel limped into port, only for the party to face further obstruction and delay from the officials and the merchants on whom they relied to continue their journey. (The English ships had departed nine days before.) During the wrangling, Cleghorn offered “every article from Europe which I possessed, broad cloth, my dressing box, fusil and pistols” but was told only cash would do. He ended paying two hundred crowns to the Vizier, seventy dollars to the customs men and, in addition, was obliged to surrender his watch.

The remainder of the journey down the Red Sea to Mocha was punctuated by further delays but was a less of an ordeal. The appearance of the name of “Sturrock and Stewart, Dundee” on the mainsail of their new ship provided some comfort, and there was space enough to take a walk on deck, when the temperature permitted it.

On 21 August, they celebrated their departure from Mocha by shaving off the beards they had “nourished” since Venice in order that their facial appearance should match their attire. Their passage across the Indian Ocean was uneventful. True, nothing could “equal the general carelessness and neglect of duty” which prevailed; the pilot had the unfortunate habit of falling asleep on duty, and repeated calls on Cleghorn’s limited medical expertise made him not a little nervous. Responding to a complaint of the captain’s, he prescribed three pills, commenting “my reputation as a physician will be exactly in proportion to the violence of the action of the medicine.”

The Message in the Cheese and the Surrender of Colombo

On 6 September, with sufficient water remaining for just four days’ sailing, Cleghorn’s vessel put in at Tellicherry, about three hundred miles south of Goa. There, Cleghorn learned from Mr. Handley, the chief representative of the Presidency of Bombay, that hostilities against the Dutch had commenced. Cochin, he said, was being invested by Colonel Petrie and an expedition against Ceylon was being launched under Colonel Stuart. The de Meuron Regiment was supporting the Dutch in both locations. Cleghorn responded accordingly:

This intelligence obliged me to explain to Mr Handley the object of my mission, to desire him to forward, by the speediest conveyance, Captain Bolle to Cochin, charged with orders from the Comte de Meuron to the Swiss troops of his regiment in garrison there to quit the service of the present usurped government of Holland and to put themselves and the troops under their command under the officer commanding the British forces before that place, and with letters from me to Lieut-Col. Petrie … telling him that, if Bolle succeeds in Cochin he should be despatched immediately to Ceylon.

He also wrote further letters to Lord Hobart in Madras, with despatches to be forwarded by him to arrange a meeting with de Meuron’s brother, the “Colonel Commandant” there.

On 12 September, the party landed through the surf at Anjenjo, near Varkala on the southern tip of India, in order to cross to Madras overland rather than run the risk of capture at sea. It transpired the Swiss regiment had not been at Cochin after all and, since Capt. Bolle’s presence there might have betrayed their secret, there was a need for speed. [17]

On 26 September, when they reached the east coast at Nagapatnam, there was a message for Cleghorn to meet Major Agnew at Cuddalore. Upon receipt of Cleghorn’s news, he had been sent to Colombo by Lord Hobart with a message for the Dutch Governor of Ceylon, Van Angelbeek, informing him of the de Meuron regiment’s transfer. However, Cleghorn had also been told that Colonel Stuart, with the 52nd Regt. of Foot, had decided to launch the Ceylon expedition early, before the monsoon, and before he could be reinforced by the defection of the Swiss. To avert “effusion of blood”, Cleghorn therefore decided to ignore Hobart’s instruction, as he explained in a letter to Dundas of 15 October:

At all events I thought it of utmost importance that Colonel Stuart should be informed by me of the real situation of the regiment de Meuron, and that the Colonel Commmandant of that regiment … should know of the transfer before the siege was commenced, or before further reinforcement of the garrison might enable Governor Van Angelback to counteract him by superior force. I accordingly went to Ceylon in an open boat, explained every particular to Colonel Stuart, and furnished him with a political arm against Columbo, which if circumstances render it necessary, he will no doubt know how to use.

… In the meantime, Comte de Meuron proceeded by land to Cuddalore, where Lord Hobart had given him a meeting with major Agnew … Major Agnew was furnished by the Comte with letters to his brother who is second in command at Colombo and with every information which can facilitate the object of his mission. And both from the abilities of the agent, and the known temper of the regiment, the Comte entertains no doubt the negociation will be finished with success, while my voyage to Point Pedro has given Colonel Stuart information which he could not have received for some weeks afterwards, my letters from Palamcotta having only reached him seven days ago.

… It is fortunate that my mission may still produce most of the advantages expected from it. Only two Companies of the regiment de Meuron were in garrison at Trincomalie, and the officers bitterly regret they were not informed of the Capitulation which their Colonel had made. Five companies are at Columbo and constitute the great part of the European force of that garrison, one is at Batavia, and the rest are at Point de Galle. If the Capitulation with these shall be carried into effect, a great additional force may be added to our army in the Carnatic, Ceylon will soon acknowledge the authority of His Majesty, and the whole of the Dutch possessions in India may fall into our hands unshackled by the trammels of a guarantee. [18]

The open boat Cleghorn refers to for his journey was a “chilenga” loaded with Madeira, linen and cheese for the forces in Ceylon. He himself returned immediately to Madras, but from Point Pedro he persuaded the boat’s owner to sail to Colombo:

… to carry an open note to Colonel de Meuron from me. In this note I only said that I had seen his friends well in Switzerland some months before. But the owner of the ship (sic) agreed to give him a Dutch cheese, into which I had put a letter informing him of the arrival of his brother in India, of the general articles of the Capitulation, and that the transfer of the regiment would be instantly demanded on the part both of the British government and his brother, the Colonel and Proprietor of it. [19]

It seems the message in the cheese got through, for Cleghorn tells us that, when Agnew delivered his letters on 8 October, the Governor.

… in vain endeavoured to prevent his communication with the Commanding Officer of the Regiment de Meuron, who knew this new situation, and waited only for an authentick copy of the Capitulation to act in consequence of it.

In July, the initial response of the Dutch at Colombo to the “Kew Letter” had been a refusal to accept Britain’s proffered protection; they suspected the surrender of their possessions would prove permanent. They acknowledged the Stadtholderate as their legitimate government, and the British as their allies, but they felt that, in respect of their territories, they were “in duty and by oath bound to keep them for our Superiors, and not resign the least part of them.” The British were to be permitted to station eight hundred troops at Trincomalee, Negombo, Kalutara and Matara but, the Dutch regretted that their shortage of money and supplies was such that they would not be able to contribute anything towards their upkeep. At a meeting of 15 August, however, the Council received newspaper reports that the establishment of the Batavian Republic had majority popular support. This caused them to renounce the Stadtholderate and to annul their earlier agreement. [20]

When van Angelbeek was informed of the defection of the regiment in India, he was taken quite by surprise. The members of his Council persuaded him to resist, suggesting they could draw on the assistance of the French fleet, or perhaps their ally Tipu Sultan. Van Angelbeek responded by threatening to make the de Meuron personnel in Colombo prisoners during the forthcoming siege. Then he was “told by the Colonel that they were now in the service of Britain, and that if he attempted to disarm them they would bring the matter to instant issue in the fort.” Evidently, this also came as a bolt from the blue. And, as the regiment comprised his best troops and would anyway not be readily disarmed, Van Angelbeek surrendered them, insisting only that the Swiss should take no part in future fighting in Ceylon. This was on 13 October. [21]

At the time, the total strength of the de Meuron regiment under the Dutch in the East was 950. It was hoped that, in addition to the contingent in Colombo, its troops in Batavia, Trincomalee and Point de Galle could also be persuaded to defect.

In the event, Cleghorn had to report that the company stationed in Batavia had been “annihilated by the climate”, that all the officers were dead, and of the privates, only thirteen remained under the command of a corporal. Of the companies at Trincomalee, about one hundred enlisted into British service “before they knew their new situation”, meaning “though they may be lost to the regiment [they] add to the force of the British army.” Cleghorn thought Agnew should have gone in person to Point de Galle from Colombo to explain the situation to the contingent there, which he failed to do. Nonetheless, forty privates in the garrison deserted the Dutch on the rumour and made it successfully to India.

With respect to the main body of the regiment, Cleghorn reported to Dundas,

Of the detachment from Columbo not a single man deserted, and except eight left incurable in the hospital all are accounted for … Such is the return which Compte de Meuron has given me; but I can say with confidence from all accounts that the regiment is in high health, well disciplined, and fit for any service …And I have not the least doubt that the Compte will soon compleat the whole regiment and always keep it at its full complement of 1200 men. [22]

Technically, Cleghorn’s mission had now been accomplished and his instructions indicated he should return to England. But Lord Hobart asked him to remain and he was little inclined to leave before the Dutch surrendered.

There were good reasons to suppose their resistance would be slight. In Colonel de Meuron’s view, despite its strong appearance, the Dutch garrison was divided into factions, and although it had been reinforced by two hundred troops from the Wirtemberg regiment, it was unequal to putting up a proper defence. Van Angelbeek himself, of course, had compromised his position with the Batavian Republic by allowing the de Meuron regiment to decamp. He also had a large property on the island that he wished to keep, and siding with the British was his best chance of ensuring this happened. As to the officers, Cleghorn wrote,

Friberg the Commandant is infirm and neither does nor wishes to do any duty. The command of the troops was offered to Hugel of the regiment of Wirtemberg, who refused it under pretence that as a Dragoon he had only been accustomed to the petite guerre. Foonander the chief engineer is a drunkard. Hupner the Commandant of the Artillery is attached to the English. He meant to retire from the service and will be easily gained if his private property is secured … [23]

With regard to the wisdom of taking over the country, Cleghorn had few doubts:

The Dutch possessions in Ceylon … must soon be added to his Majesty’s Empire in the East … It is essentially requisite for the safety and protection of our possessions in the Carnatic. Should that island ever fall into the hands of an enterprising European enemy we have no security for any part of our Indian possessions. It will probably yield a considerable revenue instead of being a source of expence.

The causes which prevented Ceylon from being so productive as might have been expected to the Dutch will be removed should that country belong to us. It was at a distance from their other possessions, and therefore required within itself a strong force for its defence. It may in the event of its belonging to Britain, in great measure trust to the Carnatic establishment for its protection.

… The Harbour of Trincomali affords, at all seasons, security to our shipping, and protects and commands the Bay of Bengal, while the facility of constructing extensive dry docks in its neighbourhood will enable the largest ships to be repaired there and will render entirely unnecessary the expensive establishment of Andoman. The extending of our possessions in any other quarter of India, by extending our alliances, frequently multiplies the causes of war, but the possession of Ceylon involves us in the politicks of no country power. The king of Candia inclosed in his island and removed from all nations around is the only sovereign we have occasion to manage. The only enemy to be dreaded is European, and these enemies most probably must be his. [24]

In order to prepare a fuller account of the country, “its revenue, its Forts and harbours, its natural history as connected with its agriculture and its commerce, and of the population and character of its inhabitants”, Cleghorn now prepared to make a tour of the country, accompanied by an old friend, Colin Mackenzie, a captain in the Madras Engineers, who had been given responsibility for the logistics of the siege.

First, they met Colonel de Meuron at Trichinopoly (Trichy, now Tiruchirappalli), where Mackenzie was given a full description of the Colombo fort, the number of the garrison and the best plan of approach. On 7 January 1796, they crossed over to Ceylon and tramped ten miles to the fort at Mannar, all the while dodging the “crokodiles, with which many little tanks abound.” After a brief stay at the fort, recently captured but judged “too strong for revenue and too weak for defence”, they separated and Cleghorn travelled by boat northwards towards Jaffna, where he was hosted by the garrison under the command of Major Barbet.

Here he noted the strength of the fort, which had lately fallen into British hands without a shot, but which he judged to be much stronger than that at Trincomalee, “which has more than once caused us so much trouble.” The country for miles around had been cleared of wood, all privately held land was “admirably cultivated” and the mares on the islands were “of a size, strength and bone sufficient to breed for the cavalry.” However, the Dutch government was reported to be “extremely oppressive”, the local population suffering from poll taxes, taxes on exemption from public labour, charges for titles “contrived to gratify the vanity of the natives and also to provide a means for the governor to line his pocket”, monopolies on items such as arrack and toddy, and “domestic slavery established to its fullest extent.”

Cleghorn’s prescription for British rule was quite clear:

All grievous oppressions ought to be annulled, all obvious inconveniences ought, if possible, to be remedied, but no violent or sudden change of the system of finance should be introduced till the possession of the island is secured. The government may then speculate with safety if it speculates with justice and give up present revenue for the prospect of a future and better secured increase of its finances. [25]

On the way from Jaffna to Trincomalee, Cleghorn was next received by Lieutenant Fair, a Scotsman from Fife commanding the post at Mallative. The house he lodged in belonged to Mr. Negal, a Dutchman, who had cleared the jungle, planted rice and brought in cattle to create a successful homestead. The lesson was clear:

As there are vast extents of waste lands capable of great produce, the ancient Dutch settlers should be encouraged to occupy them … as they are all disposed to be farmers and gardeners and it is difficult to find English who will submit in India to this slow and patient method of acquiring independence. [26]

When he reached Trincomalee, however, Cleghorn met with disappointment. He had been hoping to visit Kandy in order to obtain a better understanding of its likely reception of the British. As we have seen, however, Kandyan relations were really the responsibility of Robert Andrews, who had already headed a mission there. Moreover, Andrews was now warning that the reluctance of the Indian Government in Calcutta to back the principle of a fully protective alliance (on which Madras had sought its clarification) had made the Kandyans resentful. This, he said, was because,

… the reasonable expectations which we ourselves have raised we have disappointed and their conclusion must be that we have acted with an illiberal cunning and duplicity.

To soften his disappointment, Hobart told Cleghorn that Andrews had not been particularly well treated. “He was confined within a space of 200 yards, no person allowed to communicate with him, nor was he even allowed to see the town”. He said Cleghorn should give up the effort.

Instead, Cleghorn was invited by Colonel Stuart to accompany the army in its advance on Colombo.

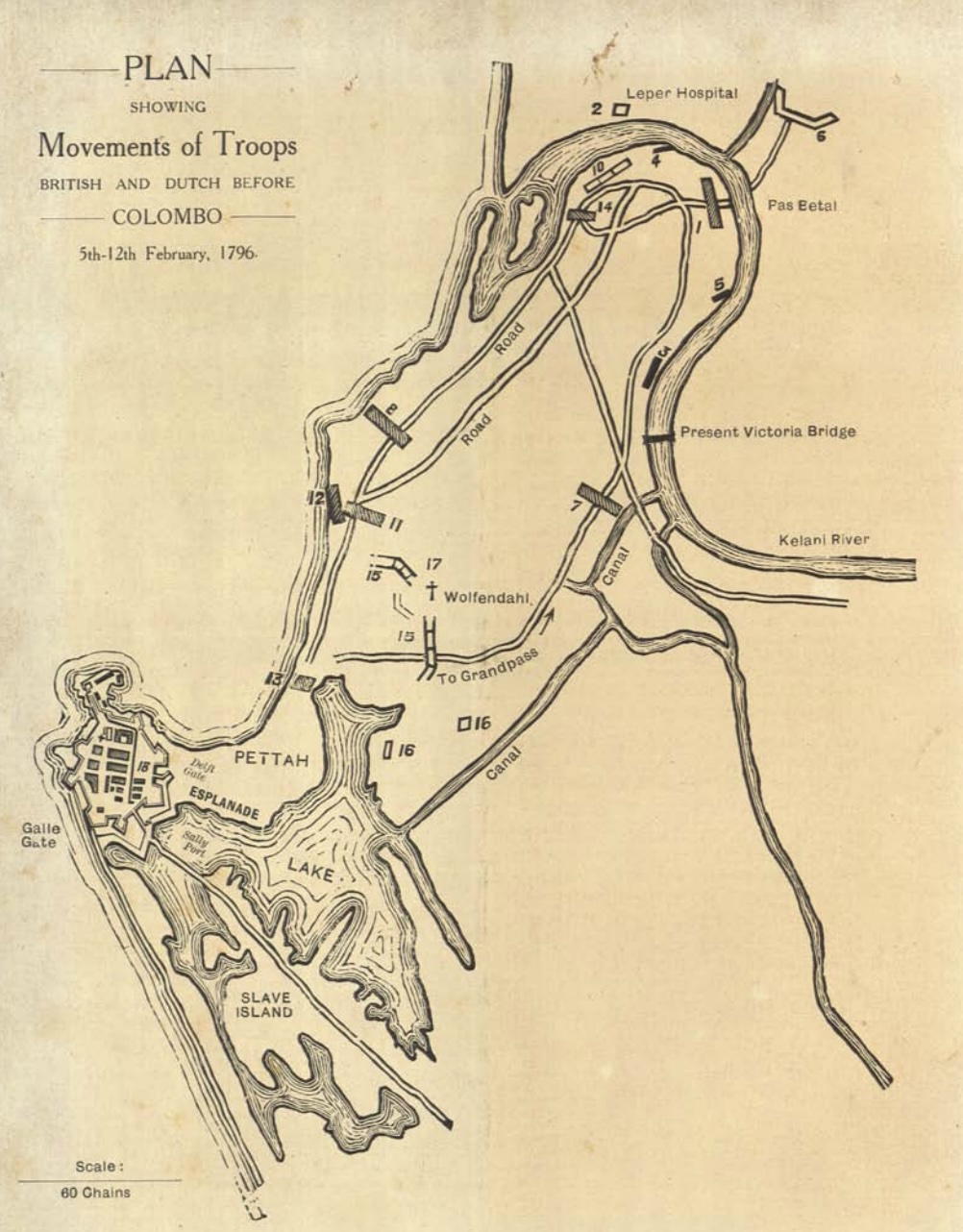

Supported by Captain Alan Gardner in HMS Heroine and the sloops Rattlesnake, Echo, and Swift, the British force landed unopposed at Negombo on 5 February 1796. There they were joined by the troops from Bombay under Colonel Petrie and a detachment from Mannar.

They faced no resistance at all until they came up against a Dutch battery at the River Motual, a short distance from their objective. There they “remained for two days in a very unhealthy situation, without tents and under heavy rains between two extensive marshes”, but only one man was slightly wounded before they learned, on 11 February, that the Dutch had decamped during the night.

A few days later, Cleghorn encountered a lone European passing on a path close to the road, at a point where it had been blocked by some felled trees. He turned out to be friendly to the British, having previously corresponded secretly with Major Agnew, and he warned that some three hundred Malays were preparing an ambush a mile ahead. The British bivouacked and, at six the following morning, an attack commenced. Cleghorn wrote,

Several shots were fired, and these daring men, armed with their creases or adder tongued daggers, advanced to the bound hedge within two yards of the front of our line, through the interstices of which they fired their fusils and pistols. A black servant of Major Barbet of the 73rd who was close by me was killed, whose body they carried off and cut off the head. This affair did not last five minutes, and I apprehend that the whole number of Malays who thus came upon us did not exceed half a dozen, and these had been wrought up to a frenzy by using Bang, an herb resembling hemp which they smoak, chew, or drink and which intoxicates them to madness.

In fact, this was but the prelude to a large assault, which the British took about a quarter of an hour to disperse, at the cost of around twenty killed and wounded.

The enemy had every advantage in point of situation, being posted upon a rising ground and concealed in almost impenetrable jungle, while the advanced corps were drawn up in a narrow road having a line of houses in their rear and a thick bound hedge in front. Both parties had artillery, but the fire of the enemy, though well kept up, did little execution. At last Major Barbet with the flank companies of the 73rd broke down the bound hedge and attacking the Malays with the bayonette compleatly routed and dispersed them.

Casualties among the Malay force were between 170 and three hundred, including Monsieur Raymond, formerly of the Luxembourg regiment, who died two days later. [27]

The British moved on and, at ten at night on 12 February, halted within four hundred yards of the batteries of Colombo. The next day was spent landing artillery and stores and bringing them from Negombo. There was no firing. On 14 February, Agnew was sent to the Dutch governor under a flag of truce. He offered the “liberal” terms that Cleghorn says he “had the good fortune to persuade” Colonel Stuart to accept, including a grant of security over private property, and a guarantee over £50,000 of Dutch money in circulation. Van Angelbeek asked for twenty-four hours to consider his position. [28]

By now, the Dutch troops at Galle had been withdrawn to Colombo to make up for lost numbers, and new native and European levies had been recruited but, inevitably, without the de Meurons, the quality of the garrison was much diminished. At Tuticorin, Pierre-Frédéric de Meuron was in a position to provide details on the disposition of the Dutch defences. At Negombo, there were now nine British warships offshore, the Kandyans were on hand with five thousand men armed with matchlocks, and a large Sinhala force was said to be advancing.

The Dutch Council considered the British surrender demand.

Your Honours must be aware [it said] that all hope of succour from Europe, from your own country as well as from the power that has usurped the liberal and lawful government of the same, is vain; and when His Majesty’s conquests on this side of the Cape of Good Hope, as well as the surrender of that fortress, are taken into consideration, moreover the strength of the British fleet in the Indian Ocean, you will also realise that all hope of help from any of the remaining Dutch possessions in Asia is equally vain.

Given the continuing lack of a diversion from Tipoo, and the absence of the much-anticipated French fleet, Van Angelbeek and the Council members were obliged to concede this was so. Recognising that the native chiefs had failed to provide the eight hundred volunteers they had promised, that large numbers of their Indian troops had deserted, that more than half their Moorish artillery had defaulted, and that there was “no more copper money in the Company’s chest”, they unanimously resolved “to propose an equitable capitulation”. [29]

On 15 February 1796, “the town and Fort of Columbo entered into a capitulation, which included also all the remaining Dutch possessions in Ceylon.”

The number of fighting men in the garrison totalled 2,770, compared with 5,550 fighting men among the besiegers. With some justifiable pride, Cleghorn signed off his last letter to Dundas from Ceylon as follows:

The Artillery in the Fort amounted to 360 guns and mortars, of which 121 are brass. And, besides the publick property found in the stores, two ships in the road have been given up whose cargoes, it is said, amount to near one million sterling.

The government debt of Ceylon in actual circulation did not exceed £50,000. This sum was borrowed in the Island and circulated as the current money of the market. It is now funded and bears an interest of 3 per cent. The holders of this species of property now look for its realization to the permanency of the English power; and England holds the Island of Ceylon for the payment of a quit rent of £1,500 per annum. [30]

Immediately, Cleghorn prepared to return to England to present his report to the government. He sailed on the Swift on 22 February, accompanied by Captain Drummond of the 19th Dragoons, Lieutenant Davis of the Navy and, following an invitation extended to him at the time of their meeting near Jaffna, Lord Camelford. His Lordship was, he said, “zealous to try what possible hardships may be encountered between India and Europe.”

We are told that Cleghorn’s companions “who had not made the voyage before and knew nothing of the dangers of an Arab port”, were in favour of disembarking at Jeddah and proceeding to Cairo by land. However, for reasons that are left unexplained, the opportunity for leaving the ship “did not occur” and so all retraced the route of Cleghorn’s outward journey to Alexandria via Suez and Cairo. There they split, Cleghorn taking a vessel for Malta and Leghorn, Camelford and Davis for Zante and Venice.

Lord Camelford Goes Undercover

In truth, Lord Camelford was keen to return as soon as possible to England in order to resume his naval career and to make his contribution to the war. Unfortunately, an outbreak of plague in Alexandria at the time of his stay meant he was detained by the Venetians under quarantine for a full forty days. As he kicked his heels, frustration at the check put on his promotion by Vancouver boiled up inside him and he now determined that the first step on his rehabilitation in the service must be “satisfaction.” Two letters were despatched to England. The first, to his mother, urged her to “make haste to get me the Rank of Post Captain that I may not throw away any more time.” The second, to his former commander, demanded a rendezvous (with seconds) in Hamburg on 5 August, with the warning that, if Vancouver refused the challenge, Camelford would ensure “the few surviving remnants of [his] shattered character” would be destroyed.

In addition, in order that Vancouver should have no excuse for evading the meeting, Camelford sent him a draft for £200 to pay for his expenses of travel.

In reply, Vancouver was unapologetic. He refused the challenge, but said he was willing to submit Camelford’s complaints to any flag officer he chose for independent adjudication. On 1 September 1796, Camelford – now back in England – reissued the challenge, face to face, on Vancouver’s doorstep. Vancouver turned to others, including Lord Grenville, for support. Grenville agreed that “a commanding officer ought not allow himself to be called upon personally for his conduct in command” and he wrote to Camelford telling him that Vancouver was within his rights to invoke the protection of the law. Camelford promised to behave but could not contain himself for long.

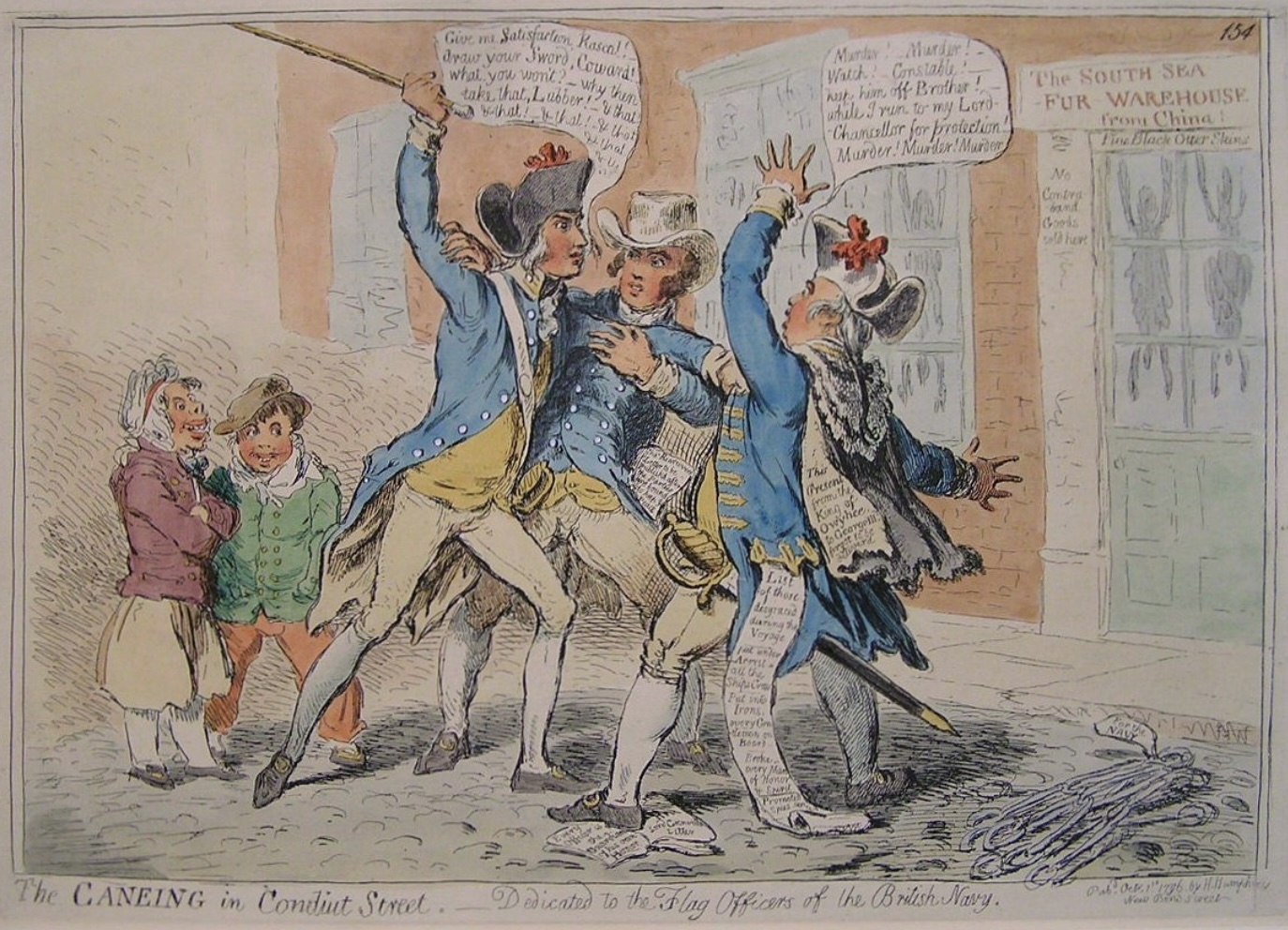

On 21 September 1796, as Vancouver and his brother were walking up Conduit Street to the Lord Chancellor’s office to apply for a suit for protection against assault, they were spied by Camelford from the other side of the road. Immediately, he dashed across and started thrashing the distinguished explorer with his stick. Charles Vancouver responded by seizing Camelford by the throat and beating him about the head. Eventually, they were forced apart, and Camelford left, threatening to repeat the chastisement whenever they should happen to meet.

On the next day, Camelford was summoned to the Lord Chancellor’s office, where he was made to promise to behave, on pain of a forfeit of £10,000 (to which Grenville contributed) if there was further violence. Although that might have been the end of the matter, inevitably it wasn’t. Vancouver and Camelford each launched a campaign defending their conduct in the papers, and the action became the subject of a celebrated caricature by James Gillray. That Vancouver was the principal butt of Gillray’s humour will no doubt have given Camelford comfort, but the fact was that the spat made him few friends in the Navy’s hierarchy. [31]

The day after “The Caneing”, Camelford was assigned to the seventy-four gun HMS London, as a midshipman. As Lieutenant Manby, late master of the Discovery’s consort, Chatham, wrote on meeting him shortly afterwards,

Before we parted, Lord Camelford opened his mind to me. With real sorrow, I left him much depressed by his situation, the displeasure of his Friends, talk of the Public and loss of Promotion Are now preying on his Spirits with every appearance of heartfelt misery.

Fortunately, Camelford got on well with his new commander, Admiral Sir John Colpoys. In January 1797, he was promoted Acting Lieutenant, and in April, this rank was confirmed. Then, in September, when on service in the Leewards, he was appointed Master and Commander of the sloop Favorite, when her captain was taken ill.

Alas, this was not to prove the happy event it might have been.

Camelford had been promoted over the head of the Favorite’s first lieutenant, Charles Peterson, who greatly resented the fact. In January 1798, as lieutenants with their own commands, they encountered each other in Antigua. There was a quarrel over who was the senior and should issue orders to the other as commander of the station. Tempers flared and Camelford demanded Peterson’s arrest. Peterson refused to oblige, armed some of his men to resist, and was shot and killed by Camelford on the dockside. It was a typically intemperate move and, although Camelford was acquitted at the subsequent court martial, in the court of public opinion his reputation sank to a new low. He was put in command of the bomb-vessel, Terror, and sent away to England. [32]

There, he was appointed to command HMS Charon. Almost immediately, whilst the Charon was still being fitted out, Camelford and a few of his Swiss friends (including Charles Philippe de Bosset, a lieutenant in de Meuron’s Regiment) were invited by Camelford’s cousin, Sidney Smith, to discuss a plan to man some Turkish gunboats and harass French shipping at the mouth of the Nile. In the event, nothing came of the plan, but the meeting with Bosset seems to have inspired Chelmsford into thinking it would be possible for him to adopt Cleghorn’s example and use subterfuge to strike a blow against France.

His first scheme was to send Bosset on a spying mission to Spanish Latin America to identify those places in Chile and Peru which were most susceptible to rebellion and which might be supported by a squadron based, under Camelford, in the islands of Juan Fernandez. Later, when it appeared likely that Camelford would be sent in the Charon to the Mediterranean, there was a refinement of this plan, according to which Bosset would travel through Switzerland and France to the naval base at Toulon and spy it out, before being collected at Leghorn.

Then, in January 1799, Camelford was arrested by the collector of customs on the beach in Dover for trying to persuade some fishermen to take him across the Channel and deposit him on a secluded beach in France. He was dressed in the shabbiest of clothes and in his coat were found a pair of pistols, some ball, powder and flints, and a dagger. Also, a letter from Désiré de Maistral, a French naval captain being sent home as part of an exchange of prisoners, whom Camelford had met that evening on the coach from London. The letter was addressed to “La Municipalite de Calais à Calais” and recommended the bearer as an ardent Republican who should be introduced to Citizen Barras, one of the Three Directors of the Republic.

At first, Camelford claimed that his name was Johnson and that he had found the letter in the lavatory. Then he admitted that he was really Lord Camelford, a peer of the realm in disguise. Since neither story appeared likely, he was bundled off to the Home Secretary, the Duke of Portland, who recognised him. To discuss the case, a special session of the Privy Council was convened. Embarrassingly, several of its members (Pitt, the Prime Minister, Grenville, the Foreign Secretary, Lord Chatham, the President of the Council) were Camelford’s relations. They chose to absent themselves.

The problem was that, at the time, it was a capital offence to travel to France, and only shortly beforehand another man, named Langley, had been hanged under the same charge. Camelford’s suggestion that he had intended to go as a tourist didn’t exactly square with the evidence and, anyway, it was irrelevant, as the charge disallowed any motive. In the end, after various witnesses, including Bosset, had spoken for him, Camelford was given a royal pardon, with the rider that he “should not be intrusted with the command of any ship or vessel in His Majesty’s service.”

There was little doubt that, as the London Chronicle put it, Camelford had “been prompted by a too ardent desire to perform some feat of desperation, by which, he thought, the cause of Europe might be essentially served.” Wearily, the Chronicle added “little doubt is entertained of his Lordship’s intellects being in a deranged state”, a view with which The Times and many others were inclined to agree. [33]

For a while, Camelford kept away from espionage but then, in 1802, during the period of the Peace of Amiens, he made one last effort. Napoleon himself was at that time in Paris and even willing to receive accredited English visitors at morning levees as the Palace of the Tuileries. Thus, it is especially intriguing to find Camelford also there, travelling under a false passport as Jean Baptiste Rushworth, and in possession of an early type of magazine pistol, capable of firing nine shots without re-loading.

He had first entered France on 26 October 1801, but it was not until 10 April 1802 that the men of Fouché’s secret police caught up with him. Fortunately, they did not find the pistol, but they had no doubt of his motive. As the official police report says,

Lord Camelford, first cousin of Mr Pitt, brother-in-law of Lord Grenville and near relative of Sydney Smith, gives much money to the émigré Chouans living in England, particularly to Limoelan, whom he sees often. His close relationship with these scoundrels gave him the idea that he himself should assassinate the First Consul. [34]

Camelford was taken under escort to Boulogne and returned to England, where The Times reported his arrival on 20 April:

A Morning Paper of yesterday informs us, that Lord Camelford is returned to England; and it adds, that his Lordship experienced the most polite treatment from the Chief Consul! It had been very differently reported in this Country, as it was said that Fouché’s Gentlemen had been very anxious to find his Lordship’s address. [35]

We can but guess what Cleghorn would have made of Camelford’s escapades.

In his last years, Camelford was best known as a patron of bare-knuckle-prize-fighters, one of whom, a giant of a man called Joe Bourke, he was determined to set in a contest against Jem Belcher, a butcher from Bristol. His first attempt at staging an illicit fight between them at Enfield Wash, in November 1801, attracted a crowd of thousands but was frustrated by the magistrates, who found Belcher hidden in Camelford’s lodgings and arrested him. (Camelford had secreted him away in order to ensure his attendance.) When the great fight finally took place, near Tyburn in August 1802, the crowd in Oxford Street and Hyde Park was so large the authorities were powerless to intervene. Belcher won in the fourteenth round, was declared Champion of England and joined Camelford’s stable. (He finally lost his title to Tom Cribb after eighteen rounds in December 1805; this was after he had lost the sight of one eye playing at rackets.)

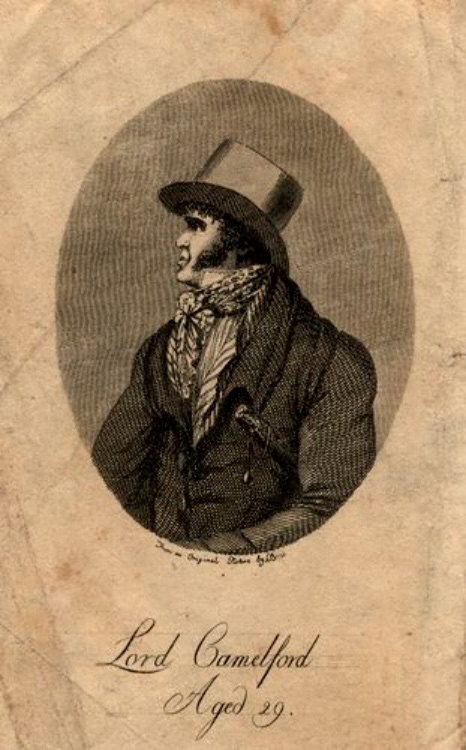

On 10 March 1804, Camelford was killed, at the age of 29, in a duel with his friend Captain Thomas Best, on the mistaken understanding that Best had made a disparaging remark about him to Fanny Simmonds, a lady whose company Camelford was then enjoying, who had also previously been Best’s mistress.

So fantastic were the circumstances of the duel that it has been suggested they may have been the result of a plot, set up by the French security services, to protect the person of the emperor from another assassination attempt. Best was known to be one of the best shots in the kingdom. [36]

The Last Phase of Cleghorn’s Career

For a period after 1798, Cleghorn became the first Colonial Secretary of Ceylon before he returned to St. Andrews and he retired to his estate of Stravithie.

Despite the wishes of Pitt and Dundas, who always wanted it administered by the Crown, British Ceylon was first governed from Madras, by the Company whose forces had conquered it. The first Governor was Robert Andrews, but he made the mistake of sweeping away the Dutch systems by which the people had been previously governed, and he introduced the taxes and imposts of Madras in order to recoup the costs of the campaign. The result was widespread disaffection, which burst into rebellion in 1797. For a period, Brigadier-General Pierre-Frédéric de Meuron was appointed chief local authority until, in 1798, Frederick North, younger son of the Prime Minster during the American Revolutionary War, was sent to take his place, with Cleghorn in support.

After an encouraging start, in which Cleghorn did much to restore the Dutch system of administration, relations between the two men suffered from North’s prickly nature, and ill-defined reporting lines between them. North started to suspect Cleghorn of siding with Madras against him. A dispute over claims of corruption in the management of a pearl fishery gave the Governor the excuse he needed to suspend his Secretary. No criminal charges were brought but, in January 1800, Cleghorn returned home and out of the pages of history. [37]

In a letter written many years later, in 1831, to the founder of Madras College, Cleghorn looked back with approval at his unconventional career:

Learned retirement of secluded leisure for study is nonsense. The world is the school of letters as well as of business. The political agitations of Greece produced her poets and philosophers as well as her statesmen; while the monkish establishments of our fathers, with their seclusion and endowments, produced only the jargon of technical language, and fettered themselves and their disciples with the impertinence of academical forms … My ardent desire to visit foreign countries has been gratified to the utmost. I have been employed by government in many important missions abroad. I was a near observer, from my situation in Switzerland, of all the great events passing in France; and to a certain extent, I became acquainted with all the great men of my time.

His tombstone in the graveyard of Dunino bears the following epitaph:

In memory of Hugh Cleghorn LL.D. of Stravithie

Professor of Civil and Natural History in the University

Of St Andrews

Who died in February 1836 and is buried here

He was the agent by whose instrumentality the Island

Of Ceylon

Was annexed to the British Empire