Early Days in Latin America

Sutton was born in 1884, in Lincolnshire. ‘My grandfather,’ he wrote, ‘was what is known in England as a Squarson – a Squire Parson.’

He owned some ten thousand acres. He preached, baptised, buried, managed his estate, and rode to hounds. He used to perform wedding ceremonies wearing his surplice over his hunting coat and top boots, while his impatient hounds gave tongue and fought outside the church.

As a child, ‘angelic in appearance and diabolic in disposition,’ as his biographer put it, Frank enjoyed heating pennies in the fire grate of his nursery and dropping them out of the window for the ladies of the Salvation Army to pick up in their fingers.

His first experiment in engineering involved building a drawbridge to a summer house on an island in a lake, and ‘defending it’ with a home-made cannon loaded with powder from gun cartridges and bullets made from the linings of tea chests. With this he blasted several wasp nests and a few windows, before the barrel burst in the hands of a cousin.[2]

After Eton, Frank studied engineering at University College, London. But the prospect of an office job held no appeal. Frank wrote,

The real business of life lay beyond the familiar horizon, down strange seas and across nameless, mysterious mountains. It was not enough to live safely and respectably within the limits of stultifying tradition. I must strike out for myself. I reminded myself that in all likelihood I was destined to pass through this world only once, and I must waste no time finding out what it was made of, who lived in it, why it turned on its axis, and the colour of its complexion.

Frank began ‘learning the way of the sons of Martha’ at work on the construction of a railway through the swamps and forests of Paraguay. It was, he said, a hard way and not always fair, although he reasoned it was ‘well to live it early, and to learn it well.’ Despite the discomfort, he later claimed these were the happiest days of his life. For transport, he adapted a motorcycle to run on flanges rather than tyres, and with a third wheel to ride on the tracks – it travelled at thirty miles per hour with a payload of three passengers, chains and theodolites. He hunted for snipe and duck, alligator and jaguar, and the walls of his house were decorated with the skins of rattlesnakes.[3]

There followed a time in Argentina working on bridges and a brewery’s waste-water plant. Returning to England in 1909, Frank then developed a type of ferro-concrete fencepost and was contracted by Lord Cowdray to use them to secure the perimeter around an oil refinery in Mexico. Since, in early 1910, he had married his wife, Carina, a period in a salaried post at Pearson & Sons was thought appropriate.

In Mexico, the substantial Cowdray empire was built around its relationship with President Porfirio Diaz. In September 1910, Diaz was elected for a seventh term. Yet, the foundations of his power proved shaky. During the campaign, Diaz had imprisoned his main opponent. He escaped and launched a rebellion. The regime tottered and Frank’s enthusiasm for his work evaporated.

He took Carina and his young daughter, Pepita or ‘Peetsy’, away from the heat and noise of the refinery to live on a sugar estate near-by, but the rebellion caught up with them and a river launch had to be sent to their rescue. As it came into view, Frank mistakenly shot and killed the boatman, in the belief that he was ‘tampering with the engine.’ The Suttons escaped, but Frank resolved simply to work out his contract.

After twelve months, his wife and child returned to England, and Frank travelled north to New Orleans and up the Mississippi. It was the coldest winter in thirty years, and, having paid for his family’s passage, he had with him nothing but the clothes on his back. Starting as a mere shoveller, he finished in Detroit as a construction foreman and saved just enough to book his passage home.

Before long, however, he was again in Argentina, where he formed an engineering partnership with Hector Rugeroni, whose wife he had come to know, in London, through a shared interest in rowing. For a period, the venture was successful. Then, at the beginning of 1913, the economy started to unravel. Bond yields rose to fifteen per cent and, with multiple new ventures in train, the finances of Rugeroni & Sutton became overextended. In his memoir Frank claimed, ‘I was going well when war was declared,’ but he was earning just £28 a month and he had sunk into such a state of depression that Carina feared for his reason.[4]

He persisted for a little longer before, in November 1914, he dropped everything and returned home, to enlist. Having failed again financially, inwardly he confessed that he was looking forward to having no responsibility and to doing as he was told. Outwardly, he wrote, it was ‘the right, the inevitable thing to do. It seemed the most satisfactory thing to do, not particularly serious and certainly not to last for long.’

Gallipoli and the Ministry of Munitions

Recruited into the Royal Engineers, for a while Frank was bounced around the Mediterranean. No one seemed to know what to do with him:

I did have a bag of golf clubs and a bed roll, as it seemed likely the I would be assigned to construction works in the rear. Armed with these, and full of hope, I was sent on to Cairo, where there were, I believe, over one hundred Generals collected. One of them returned me to Alexandria, to get rid of me, I dare say. The streets of Cairo were cluttered with morose, foot-loose Lieutenants, even as I. Finally, I was packed on board a ship destined for Gallipoli. But first I wrapped up my bag of golf clubs in burlap, and marked them ‘theodolite legs’, which seemed more in keeping with my profession. They gave me a detachment of thirty men, and there I was! An R.E., going to Gallipoli! This was better than Malta and a great deal better than Cairo.

As he landed on the beach, a piece of shrapnel hit the golf bag and revealed its contents. ‘The fellows under the cliff cheered the ruddy toff who went to war with his golf clubs,’ Frank admitted, but he took them ashore nonetheless. [5]

In May, he was sent forward to a point being held by the South Wales Borderers and the Gurkhas. With him, he took a mixed company of ANZAC and British miners, whom he intended to use ‘to give the Turks a shake-up.’

The Turk had no love for bombs and mines. He hates to be blown to bits, for a scattered Turk doesn’t get to a Turkish heaven. He must arrive at the gates of Paradise neatly assembled and in good anatomical order to be persona grata. I planned some mines for his undoing …

One night out scouting by myself I was caught by the daylight and unable to get back to our lines. I found myself in an isolated shell-hole about twenty yards from the Turks’ forward position and held by five Gurkhas with a machine gun …

A wounded Tommy crawled over the edge, after a counter-attack from our lines. He was badly hit in the leg and quite helpless. We propped him up on the fire-step, with his leg elevated, and he lay there watching the fun. He was a good gallery, save perhaps for one thing: he was over-enthusiastic. I have good reason to remember his very partisan behaviour. He wanted our side to win, wanted it in the worst way. Turks don’t always take prisoners, and this particular Tommy couldn’t run.

The Turks soon tired of firing at us … Then they started pitching hand-grenades about the size of cricket balls and set with an eight- or ten-second fuse. It took them three or four seconds to get over to us, and I was able to catch them and send them back so that the grenades exploded in the Turkish trenches. This much I had learned at Eton: I was always a safe field.

I was bound in course of time to miss-field, and I did. One of the grenades came over high and fell sputtering and fizzing in the sand at my feet. I stooped to pick it up, saw that it was too late – eight seconds is only a split fraction of infinity – and pushed it as far into the sand as I could. I knew that the men would be clear and I intended, myself, to jump back and be ready for the next one. There was a dull explosion. I felt my arm jerk as if it had been struck a blow. I was thrown back across the shell-hole, half blinded, my eyes and mouth full of sand.

The Gurkhas had scrambled away, but Frank’s arm was blown off at the wrist and so he and the Tommy were virtually defenceless, as a ‘regular whale’ of a Turk jumped into the hole and lunged at them with his bayonet. He aimed his first thrust at Frank’s stomach but was parried and ended driving it into Frank’s leg. They fell grappling to the floor, the Turk at Frank’s neck, the Tommy hurling a rock at the Turk’s head but missing and hitting Frank instead.

I groped about on the ground with my left hand, thinking to retrieve the rock, and touched instead the sharp curved knife of a Gurkha, abandoned there, and now a very useful and unexpected weapon. I had already bitten off my Turk’s ear, without disturbing him at all, and now with my last strength I stuck the knife into his throat. He roared. I could smell his hot breath, reeking, suffocating. His blood spilled over me. I had him. Slowly – I will never forget how slowly – he relaxed. His fingers fell away from my windpipe, one by one. He jerked his head up and down to escape the insinuating blade, striking it deeper and deeper. Then very quietly, with a certain dignity and leisure, he rolled off me, and lay on his back in the sand.[6]

Frank was awarded an M.C., but he took no further part in the fighting. His ‘affinity for bombs’ recommended him to the Ministry of Munitions, where he was quickly persuaded that ‘the traditional impedimenta of the Barking Generals and empurpled Majors [were] Germany’s greatest asset.’ Churchill and Lloyd George, he wrote, had done well to sidestep their malign influence: one of their signal contributions to the war effort had been to issue strict orders to the Zeppelins ‘to steer clear of Whitehall.’ London, of course, remained a target for their attacks and, in his autobiography, Frank recorded with some glee how one of them met its end over the southern suburbs:

High up in the sky we saw a little red light like the tail light of a motor car: an aeroplane pilot’s signal to cease fire and to give him his chance. The great Zeppelin, no longer silvery, showed like a shadow upon the smoky darkness of the sky. Two minutes. Then, as if a giant up there had struck a match to light his cigar, the first incendiary bullet hit the dirigible in front. A ribbon of fire ran the whole length of the envelope, swifter than the eye could follow. Then, all at once, she burst into flames and people eight or ten miles away could see to read newspapers in the glare.

The great burning ship tilted first one way, then the other, and a wild roar of cheering swept over the city from the East End to the West End. Everyone rushed into the streets. It was pandemonium. She fell in a field in the suburbs of London. I crashed the hospital gates, eluded the sky-gazing guard, jumped into a taxi, and drove ten or twelve miles to the scene of the wreck. The red-hot framework, twisted, charred, spread over an acre of ground.

At the ministry, one of Frank’s roles was to assess ideas for new weapons that had been suggested by members of the public. These included ‘musical’ bombs with long wireless fuses. For four or five days after they had landed, they would do nothing, giving the enemy such a false sense of security that they would be adapted for use as ‘arm-chairs, porch ornaments, footstools and paper-weights’ before they exploded. Someone else suggested a gun with a curved barrel designed to shoot around corners. Frank looked for opportunities to get away.[7]

By 1917, it was apparent the Americans would enter the war, and so Frank persuaded Armstrong Whitworth to assign him to Philadelphia to sell trench-mortars. These incorporated several of Frank’s own refinements, including a new kind of cone fuse. Frank was well-received and by the time he left America he had received a lump sum of £15,000 in lieu of royalties on his fuse, the rights of which he assigned to the US Government (a decision he came later to regret). [8]

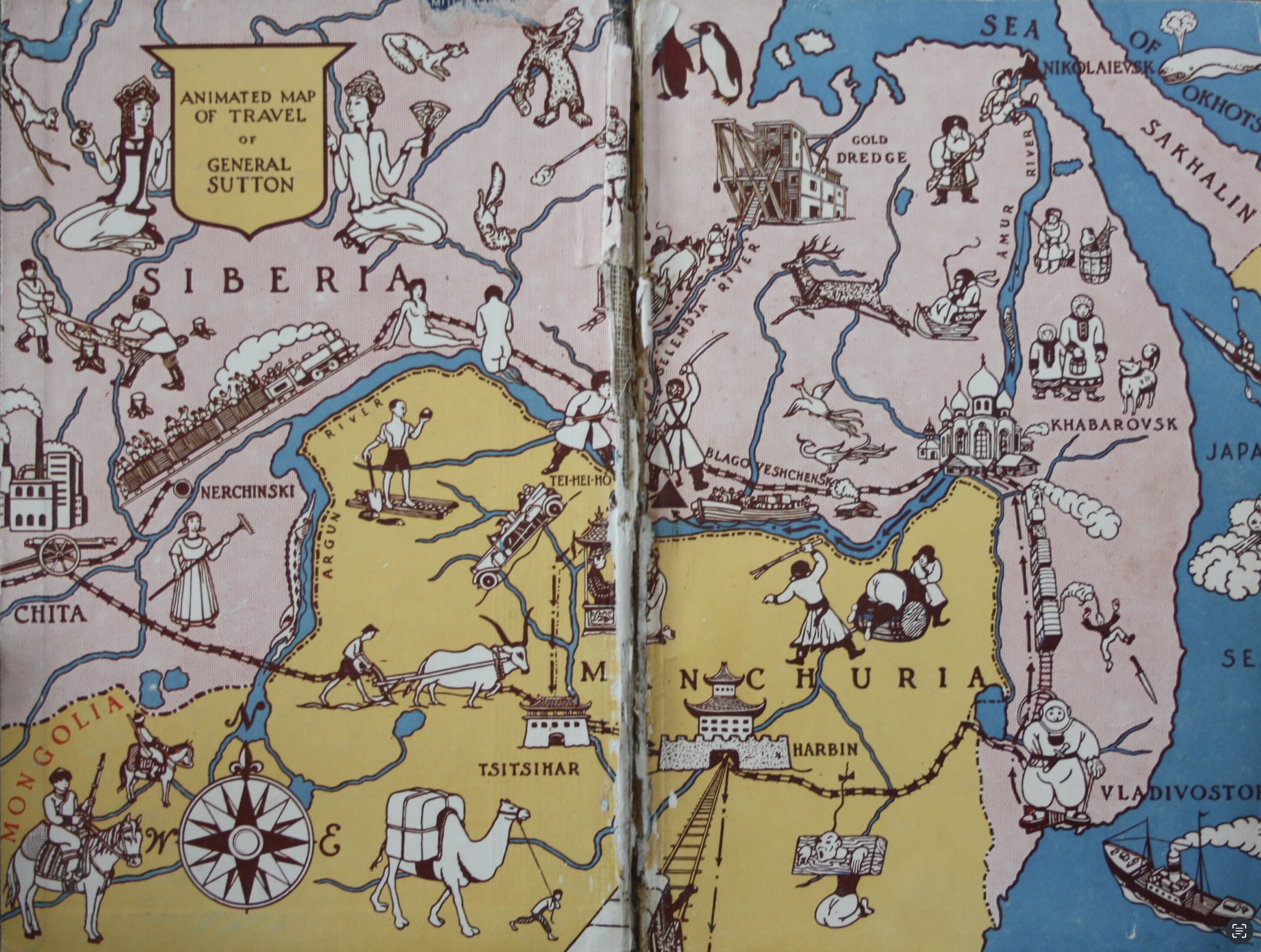

Siberia (1919 – 1921)

Determined, on demobilisation, not ‘to charge at life with an umbrella,’ Frank was unsure what to do next. Then, remembering that, in Philadelphia, he had heard of a placer-miner who had found gold two thousand miles inside Siberia, he decided there was scope for a large profit, if modern dredges could be applied to the task. He sent an experienced dredge-man to investigate. His report, when it arrived, read:

Placer creeks better than expected. Great opportunity for dredging. Political situation improved. Country apparently secure under Whites.

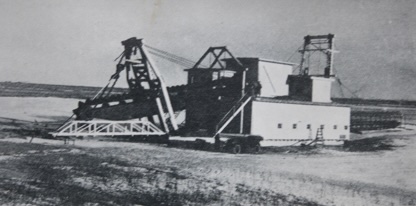

In January 1919, Frank sailed for San Francisco and a rendezvous with his scout. In a grubby hotel room, they met over a table onto which the miner poured from a greasy ‘poke’ a handful of nuggets and gold dust. Frank was hooked. In the following six months he assembled the equipment necessary to extract the gold from two thousand tons of gravel a day. This was shipped to Vladivostok, where it was to be united with a barge made from Siberian timber.

Persuaded by his friend there was a second fortune to be made supplying Siberia with the goods that were everywhere in short supply, he added to his cargo a thousand tons of manufactures – ten thousand pairs of shoes, fifteen thousand barrels of assorted nails, fifty tons of horseshoes.

Little did Frank appreciate, when he departed, that the Bolsheviks were passing through the Urals. When he reached Vladivostok, they had already taken Tobolsk. It was far enough away, perhaps, to claim conditions ‘outwardly, were fairly good,’ but Frank conceded that the White regime on which he pinned his hopes had turned a shade of pink. ‘Like the deceptive radish,’ he wrote, ‘Siberia was both red and white and when bitten into had a peppery taste.’ However, he was not to be diverted, not even by the better-established mines that were closer in Korea. In a letter to his mother he wrote,

We are living on top of a volcano and at any moment we may have a rising of the Reds and more murdering. Kolchak’s government has not got the confidence of the people and many of his troops have deserted to the enemy. It does not look promising, but anyhow I’ve got so far and now I’m going on despite of all the whiskered Russkies in the country.[9]

The immediate challenge was to get the equipment and goods to shore and seven hundred miles up the railway to Khabarovsk. There, the dredge would be loaded onto its barge and steamed for eight hundred miles up the Amur River to Blagoveshchensk (Blago) and thence, up the Selemdzha (‘Selemdja’) River, a tributary of the Zeya, to the gold fields. All of which had to be achieved before the freeze set in. Of Frank’s prospector there was no sign, and he would have been hard pressed had he not overheard a foreman instructing a gang of roustabouts at the dockside, in Spanish. Aleck was a Russian who had spent twelve years driving a locomotive in South America. He and Frank had become acquainted in Argentina.[10]

The first need was to obtain a train. The governor, recently attached to the Russian Embassy in London, would have liked to help but he objected that the town’s rolling stock was needed to help troops repel Bolshevik attacks on the railway. This was dispiriting intelligence. However, a means was found to fix the problem when the governor mentioned the impossibility of building a home on the pittance that was his new income. Ten barrels of nails were sent to him as a gift, and forty goods cars became available. An additional accommodation car at the rear – ‘a filthy, odoriferous box’ – was scoured with disinfectant and fitted with a cooking stove and a barricade of sandbags for protection against snipers.

There followed a fraught interval when, during unloading, the dredge’s bucket fell into forty feet of water and Frank had to don a diving suit to recover it. ‘The fellows up above,’ he says, ‘were over-zealous and, since with one hand I could not easily manage the stop valve, they over-inflated me and very nearly blew me asunder.’

Loading the trade goods also required careful supervision. Frank found that the town was full of thieves, many of whom had become his employees. On one occasion, he slipped behind a box car and found two carts backed up on the other side, with a gang of men receiving barrels of nails as fast as they were loaded. On another, sixty pairs of shoes were discovered under the floorboards of the inspector’s office.

The party left Vladivostok at the end of July. The bridges and culverts along the line were guarded by detachments of Japanese troops, with patrols of Cossacks and White Russians in support. There were days when the train covered as much as fifteen miles. On others, it managed just ten and, on some, it actually went backwards. Frank wrote,

It was useless to argue with the locomotive-drivers. They had panics of their own. Bolsheviks were reported ahead. Or marauding bands of armed horsemen were said to lie in wait at the next bridge, or perhaps the incessant sniping had weakened their nervous resistance.

He was advised to bank the stove at night as, after dark, the sparks it threw off attracted attention, causing the accommodation car to be peppered with bullets.

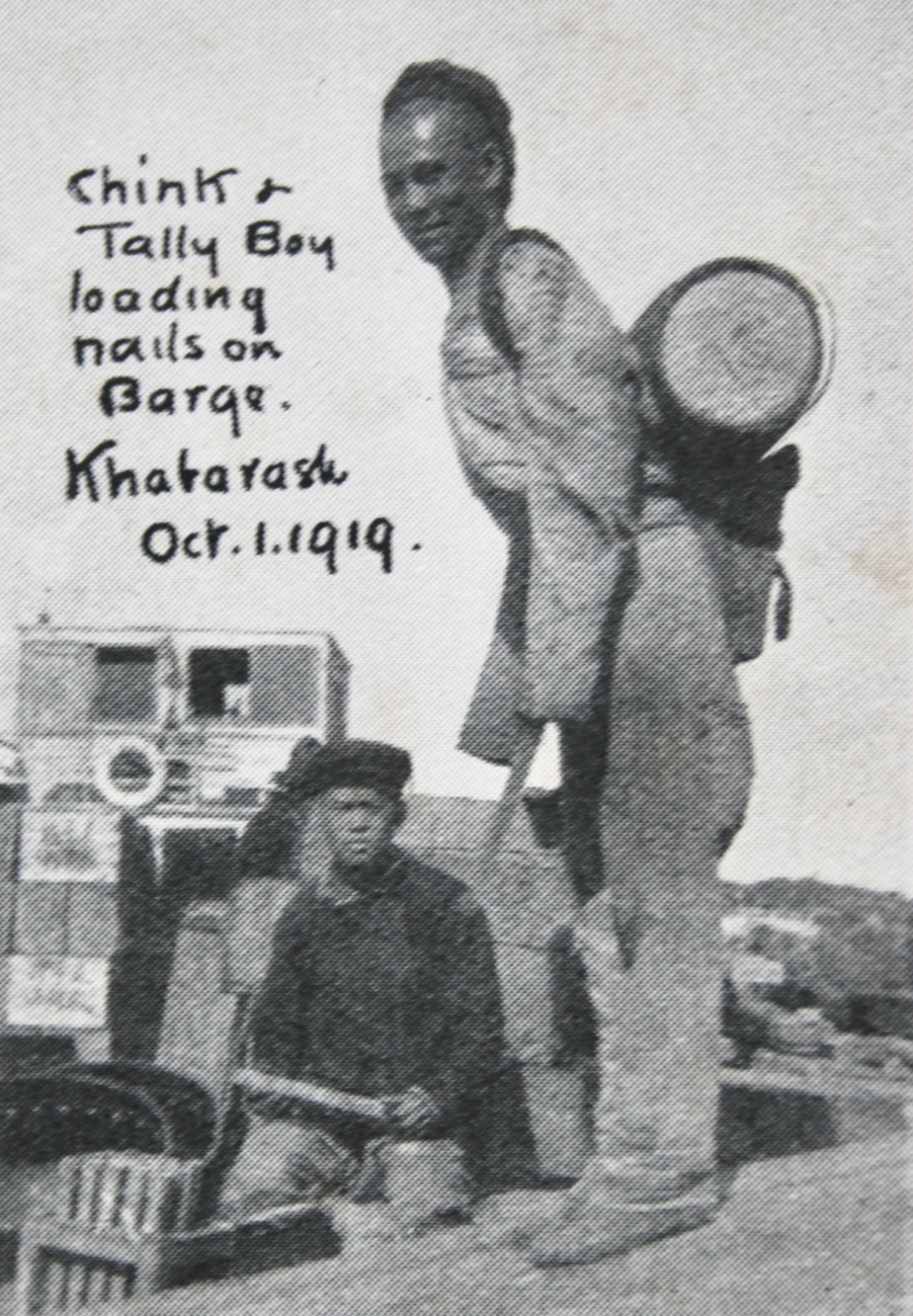

After an eventful journey, lasting seventeen days, in which Bum Hi, the Chinese cook, was pitched out of the car for attacking Aleck with a carving knife, and an old Swedish captain, who enjoyed baiting the Cossacks, received a sword blade through the shoulder for his pains, they reached Khabarovsk. Here the burden of bribery was even greater than it had been at Vladivostok. Nor were exchange values easy to determine. The palms seemingly of everyone were dusted off and crossed with roubles, yen, dollars, nails and shoes:

Canny whiskers, with an eye out for profit, always demanded gold or silver; to them I gave dollars, or else shavings from a gold-bar that I carried with me. Like a plug of ripe tobacco, this bar was bitten off little by little; it vanished into the greedy maw of officialdom.[11]

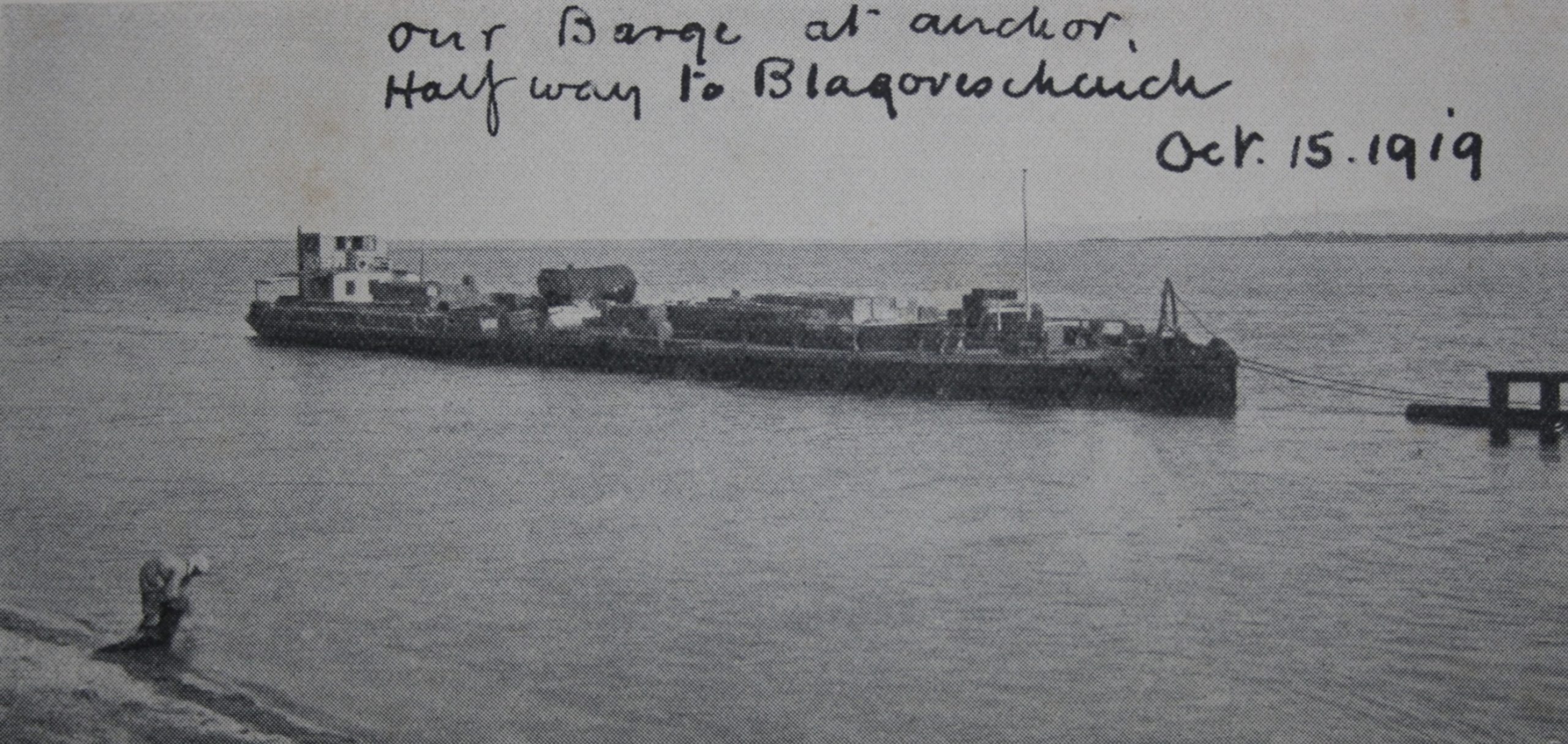

Eventually, Frank obtained a tug and some lighters, and, on 7 October, he set off up the Amur.

Frank lived on one of the barges with Aleck and two Chinese carpenters, who spoke a little English. The barge-master and his three-hundred-pound wife occupied the deck house and, since the atmosphere within was ‘as thick as old cheese’ and ‘altogether too gamy,’ Frank slept on deck. Danger was at its greatest when the convoy had to stop in order to replenish with the timber it used for fuel. One night, after about five days’ voyage, Frank was awoken by a volley of rifle fire and the sound of bullets clattering on the deck around his sleeping bag. In no time, a group of ten Chinese bandits (‘Hun-Huntzes’) were onto him ‘like a winkle in its shell.’ At the same time, a larger group of about a hundred swarmed out from behind a woodpile onto the tug ahead.

They hauled me to my feet, and a pockmarked gentleman, evidently their leader, put a revolver to my head … This was a nervous business; the revolver was old and decrepit and he had to hold the hammer back with his thumb. There was in his narrow glittering eyes the flicker of a doubt, a most damnable and terrifying uncertainty. I watched not his eyes but his thumb … It trembled on the hammer as he wrestled with the notion to kill me. Was I useful alive? Or was I safer dead? Or could he wound me, get what information he wanted, and finish me off at his leisure? His pockmarked face puckered at the stress of his indecision.

Frank was manhandled into the deckhouse, where the bandits turned their attention onto the barge master and his wife.

The bandits leaped at them with greedy snarls and searched them. They did a thorough job. One of them … thrust his fingers between the old Russian’s lips, pried his teeth apart, and searched his mouth. The poor old chap’s face became gorged with the blood of his helpless rage. They tore at his wife’s bodice, ripped off her skirt. All the while she screamed at them. They might as well have been deaf …

The others continued their search until they had about a hundred roubles: twenty-five cents in good money! This did not seem to satisfy them. They grumbled and complained, poking the two Russians with their knives, demanding more.

‘Give them everything you’ve got,’ I said. ‘They’re getting ugly. They’ll kill you.’ … Violently the fat woman shook her head. ‘Niet! Niet! Niet!’ she shrieked.

At that the strongest of the band seized her, turned her over a barrel, lifted her voluminous petticoats, and spanked her with a bamboo. She kicked and cursed and foamed. It was a Rabelaisian scene. There was something horrible about it. Ridiculous and horrible at the same time. They hit her a dozen stinging cracks while her husband wept and pleaded. Great tears rolled into his beard.

All that this effort revealed was a further three hundred roubles hidden in a pouch under a mattress, and so the bandits descended into the hold, where they discovered Frank’s trunk. His money and rifles had been secreted away in the cargo, but inside the trunk was the English attire he had been pleased to acquire for himself in San Francisco. Frank recalled that, as he raged,

I saw my precious wardrobe snatched at and divided among them: evening clothes, heavy underwear, ties, vests, overcoats, shirts, mufflers, hats, caps, shoes, and socks. In these things, save only the collars and shoes, they attired themselves, grinning and chattering the while, more like monkeys than ever. I saw my good coats adorning the sharp-bladed backs of cadaverous Chinks who didn’t know the meaning of soap and water. I saw my pants worn backwards by filthy simians who would have murdered me for a copper. My hats sat upon shaggy heads alive with vermin …

At this juncture, the bandits discovered a five-pound box of chocolate liqueurs. Not having experienced their like before, they were unprepared for their taste, and feared they were poisoned:

‘For God’s sake, Aleck,’ I cried, ‘eat one of the chocolates! Prove they’re not poisoned. Give me one, too. Quick! Pronto!’ He swallowed, grinned. ‘See? No poison! Good! Fine!’ We rubbed our stomachs in ecstasy, and ate and ate and ate …

They reached cautiously for the bonbons, tasted, swallowed, giggled. Indeed, a fine time was had by all, at my expense, and, now that they had satisfied themselves that I did not mean to harm them, they became all at once very friendly. The party was over. They swarmed out of the hold, over the side, and ashore …

In return for my possessions, the Hun-Huntzes had awarded me life, leaving me only a pair of tattered pyjamas and a miscellaneous lot of shoes and collars. I am afraid I was ungracious enough to be surly.

Frank made for himself a suit of tarpaulins lined with cotton waste and tied together with string. It was, he said, ‘the most terrible suit ever fashioned for a white man.’ To compensate, he resolved that, when he reached Blago, he would buy himself a hat.[12]

Aleck, however, had had enough, and he decided to depart. ‘The girls in this part of the world,’ he declared, ‘are too fat and silly and I prefer them in Vladivostok, where they wear high heels y son muchas mas simpáticas!’ Frank tried to persuade him otherwise. There might well be pretty girls at Blago, he argued, just as there had been at Khabarovsk, where many had been seen sporting necklaces made from five-dollar gold pieces, won from American soldiers. He was unsuccessful. Aleck went ashore at Raddo, where he was almost immediately put to work by the Whites. When, a few days later, the Reds arrived in the town, they caught him repairing a wire at the top of a telegraph pole. ‘Always a diplomatist’, explains Sutton, he descended it ‘an avowed Red’, and so ‘he had to content himself with the robust feminine charms of the peasant women of the neighbourhood.’

Their paths were to cross again after a little more than a year.

Four to five days beyond Raddo, as the barge drew up to the outskirts of another village, a brisk fight was seen to be going on ashore.

Two years before, Siberia had gone red. But reaction had set in. The Whites were in power now, all the active Reds having disappeared into the hills, where they lived like wild animals and made periodic raids over the countryside, terrifying everyone, looting, killing. The Whites were guilty of cruelty and bloodshed, too. One of their frequent, ruthless conflicts was in progress. Two or three hundred Cossacks were fighting against an equal number of Reds on the outskirts of the town…

The boobish population, indifferent to life and death, looked on with dull eyes, while the village burned, and wounded men writhed and howled in the streets. I am always for the weaker side … but in this instance I could not in all honesty determine which was the lost cause. They were, both Reds and Whites, resolutely, painfully comic. As for the innocent by-standers, they had all of the heroic resistance of cows. They stood, ruminating, while the battle raged around them. There was, in their stolidity, their inanimation, all of the tragedy of Tsarist Russia, the futile groping and misapprehension of the future.

On this occasion, from behind a dredge-bucket, Frank fired a few shots of his own, ‘without political preference.’ He was to have recourse to his gun again when, on the final approach to Blago, a boat manned by a dozen men, two in the bow with rifles, crept disconcertingly out of the fog. By shooting them, Frank sought to obtain retribution on the bandits at whose hands he suffered earlier, but he could not see them clearly, and they turned out to be Russian Bolsheviks. As a consequence, he spent two weeks in prison. It was, he confessed, ‘only by the grace of God that I escaped a dirty end in front of a firing squad.’[13]

He had arrived, in November 1919, in a shower of frozen sleet, and with ice running thick on the river. All was not well:

Gangs of unemployed workmen loafed and quarrelled along the waterfront, or hung about the streets, staring sullenly at the more prosperous citizens. They were big, tough, ugly-looking fellows, these loafers, many of them ex-convicts, or descendants of Tsarist political exiles; consequently, they had no sympathy for Kolchak or the White Army … There was an undercurrent of distrust, betrayal, terror. Fear stalked the streets, spoke in the eyes of the people; there was a distressing, omnipresent air of watchfulness and suspicion.[14]

In the circumstances, Frank decided that having just one hand put him at an unnecessary disadvantage. He equipped himself with a menacing, six-pound hook, which a blacksmith made from a half-inch iron bar and attached to the stump of his right arm. It was, he decided, a valuable, innocent-looking weapon.

Once you hook a man toward you [he wrote], you can finish him off with a quick left to the jaw—like gaffing a salmon! … There would be no slipping out of clinches while I wore this thing; once I hooked my man, he was mine for punishment.’[15]

The town itself offered a few large brick buildings, but most – even the onion-domed churches – were of wood. This was positive from the perspective of nail demand but, by the time the cargo had been unloaded, the Amur was frozen from bank to bank and the fog of the first day had turned to snow. In the circumstances, Frank was fortunate to secure, in place of Aleck, the assistance of a Greek who spoke excellent English. Andrew’s family had once earned a good living as bakers to the Russian army, but the collapse of the rouble had ruined them, and he was now reduced to selling bootleg alcohol in Heihe (‘Tei-hei-ho’), on the Chinese side of the Amur. Some of it he shipped to Blago, where he mixed it with water and sold it as vodka. The two were to develop a long association.

Immediately, they rented a house with a boy, a cook, a Chandler car, plenty of vodka and, for offices, two rooms in the best hotel in town. Living was cheap – it was practically impossible to spend a dollar a day – but the dredge was a problem. If it were not moved on soon, winter would be spent hibernating in Blago and, if they waited until the thaw, the subsequent short summer would be lost before the barge and its machinery might be assembled.

As soon as the snow had hardened sufficiently, therefore, they set out on their five-hundred-mile journey up the Zeya and Selemdzha rivers, conveying the components of the dredge on horse-drawn sledges. Before long, they encountered ice jams six to eight feet high, some of which they blasted with dynamite. The journey took a full forty days and nights but, fortunately, at their destination, there was ample wood to make the workforce comfortable. A summer’s dredging seemed certain. Frank and Andrew returned to Blago to deal with the trade goods. [16]

Yet, on approaching the city, they were greeted by a pall of smoke and the sound of shots. Their hotel was alight.

Some eight thousand Reds, who had been living in the hills, had swooped down on the city. They swarmed through the streets, big, whiskered fellows, their rifles slung across their backs. All the toughs and renegades swarmed out to join them. The Whites, terrified, fled across the Amur to the Chinese side. Some of them made it. Those that did not were being hunted like rats. The place was a madhouse.

Frank and Andrew saved some of their possessions from the hotel, but their house was requisitioned by the Bolshevik commander-in-chief. Incensed that he was to lose six months’ advance rent (all of five dollars), Frank protested to the new governor.

He revealed himself to be a ‘kindly, mild-mannered’ fellow, a retired schoolmaster exiled to Siberia for some petty offence. Persuaded by Andrew that Frank was a trader with influence and the Midas touch, he took them on a tour of the city to find alternative accommodation.

As they stepped into a familiar-looking car, Frank claimed it as his own. Covered with confusion, the governor apologised. ‘Such things are most embarrassing. But war and revolution are never polite!’, he declared. Frank offered it as a gift and was rewarded, for a house, with the Russo-Asiatic Bank, brick built and the strongest in Blago. The scenes of disorder within made even the governor blench, but the manager’s abandoned apartment upstairs had running water, comfortable beds, even a bathtub.[17]

As soon as Frank and Andrew were settled, baskets mysteriously began to arrive at the back door. The remaining Whites were sending them their wine for safekeeping, and the shelves in the basement were soon crowded with bottles and casks.

Since their occupation of the city, the Reds had imposed an alcohol ban, but the Russo-Asiatic Bank they permitted to operate as ‘an oasis in the desert.’ The commissar and his henchmen were frequent visitors, and on most evenings in the banking hall, squads of Reds were to be seen dancing to the sound of the hand grenades rattling on their belts. On one occasion there was a singular interruption to the festivities:

A bright-cheeked lad, a little drunk, perhaps, or a little mad, unhooked one of the grenades at his waist … ‘I’ve carried this damn thing around with me for a year,’ the Russian lad said. ‘I don’t believe it’s any good!’

Slipping the safety ring off the handle before any of us could stop him, he pitched the grenade across the room against the wall. It bounced behind a sofa.

I slid for the door just as the thing went off. His question was answered. Every window in the bank was shattered. Two of my guests were grievously wounded, and there was a hole through the floor into the cellar.

After that I had a sign printed for display in the entrance hall: ‘Visitors will kindly leave hats, coats, and hand-grenades in the hall.’[18]

Frank did what he could to help those Whites whose houses had been commandeered by the Bolsheviks, many of whom were forced onto the streets. He bribed the commissars to secure them relief, although the drain on his cash was substantial. Then he learned that there were $40,000,000 worth of gold bars and $20,000,000 worth of platinum – the last of the Tsarist reserves – in the vaults of the government bank across the road. Might they be used to catalyse a market in shoes and nails?

Unfortunately, the shoes – all ten thousand pairs – proved to be completely unsuited to the Russians’ broad, high-arched feet. None would fit. Andrew thought of a solution: advertise them in the Amurski-Pravda newspaper, on page two, alongside the notices of obituaries and executions. ‘Everyone reads them,’ he argued, ‘They’re good and spicy. Russians tell the truth about their dead.’

The ruse worked. Having broadcast the arrival in Blago of the Latest Correct Fashion from America. Smartest Cut. Positively Authentic Fashion Hint from New York and Paris, they visited the commissar:

We had planned to sell the shoes at a small profit for seven dollars a pair; therefore … we were surprised to hear him say: ‘Tear up your price list, my friends. We don’t pay seven dollars for shoes. We pay fifteen. Let us leave it at that. I will call a meeting at which you will state your price and display samples. All I ask is a little commission of three dollars a pair, to be shared between myself and a few influential friends. You understand? Don’t be upset if we are a bit rude to you at the meeting. We have to pretend loyalty to our own people. But there will be no difficulty.’

So it proved. The fifteen dollars a pair (less a five per cent discount for cash) were obtained in the form of a cheque drawn on the Chinese bank in Heihe which, amazingly, was honoured. Returning across the Amur with a suitcase full of Bank of China bills, Frank doled out a $30,000 reward to the commissars at that evening’s party.[19]

Almost at once, the nails also sold at a profit. Then the horseshoes. There remained only the dredge. As soon as the ice melted, Frank returned to the creek on the Selemdzha. For six weeks, he extracted two and a half pounds of gold a day, and it ran eighty-five per cent pure.

The workers were not unobservant. Comprehending that Frank had some $20,000 of metal locked in his cabin, they began to question his rights, eventually declaring that his share should be just one twentieth of the total. Since they were armed with rifles, reasoning with them was difficult. So, the next morning, at 3am, Frank did a bunk, taking the chief engineer and the Chinese cook with him.

Then, having deposited the gold at Heihe, he returned to Blago where, using the tactics which had served for the shoes and nails, he sold the dredge itself to the government for $100,000, less a commission of twenty-five per cent.

He was able to leave Russia more than whole. Yet, the reserves in the government bank were not yet exhausted. They were melting like snow in summer, but Frank was determined that the Bolsheviks should be persuaded to share what remained.[20]

Unfortunately, before he could get started, he was asked to organise Blago’s Navy. The commissars knew of his gunnery expertise, and – by one means or another – a six-inch naval gun had found its way into the city. Selecting the stoutest looking paddle steamer, Frank strengthened its hull using angle irons and baulks of timber wedged into the chain lockers. He replaced the gun’s broken pedestal with a Siemens Converter obtained from a nearby foundry and fitted it to the forward deck. He then repaired the breech block, attached some sights and fashioned a hundred shells from cast iron lined with tin, extracting the TNT from some abandoned field gun shells. They wouldn’t have passed a Woolwich inspection, but he judged them good for purpose.

On the big day, the Navy High Command, immaculate in their white cotton uniforms, boarded the Leon Trotsky, resplendent with freshly painted hull, shining brass and a fluttering red ensign. To the accompaniment of massed bands, she nosed into the stream only for the ensign to foul the stern wheel. The flag staff snapped off, and it and the Hammer and Sickle floated gently downstream.

Unfazed, the admirals took their flagship upriver and searched for a target. They lighted on a first farmhouse, but were informed by the engineer that it belonged to his uncle. They spotted another which, after much argument, they judged to be five versts inland. Fortunately, this proved to be an overestimate. The shell passed comfortably overhead and exploded, convincingly, on a hill behind. Through field glasses the occupants of the house were seen running in all directions. This made the voyage highly satisfactory. It became more so when, on the return journey, the Trotsky shelled a passing junk and severed its mast like a broken match.[21]

The Navy of the Far Eastern Republic steamed back to base and Frank was lauded as a hero. He seized the moment to launch a new business drive.

Engaging the Amurski-Pravda, he initiated a campaign for Blago’s economic renewal. Under the slogan ‘Use the Hammers! Make industry a fact not a symbol!’, he declared the key prerequisite was the materiel that only he could provide from overseas. In no time,

The Commissars began to place orders with us, each department vying with the other to put in the largest order and to get the largest squeeze. Cheques for immense sums fluttered down on our desks like leaves, the Commissars adding a few noughts at random. They were so accustomed to dealing with hundreds of millions of roubles that a cheque for a few hundred thousand dollars looked niggardly …

Orders for a million and a half dollars poured in. They wanted iron bars, copper, zinc, tin, coke, pig iron, glass, and even more nails – two thousand tons of raw material. We received seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars, cash down, the rest to be paid on delivery of the goods.

Frank banked the money in China, collected his family in Shanghai and sailed for Japan. When he returned to Blago, just before the return of the ice, the commissars were flabbergasted. They had fully expected him to take their money and run.[22]

He was an anomaly: an honest man. Which is why, when he urged the commissars to order ten dredges to kickstart the gold industry, they almost bit off his left hand. They offered a million in cash and another million on delivery.

We spent four days in the vaults of the government bank weighing gold bars. Already as we put aside that incredible million, we considered it our own. The future looked rosy. We allowed our imaginations to run riot, building castles, launching yachts, endowing universities … But a turn of luck changed our sure thing into a grave doubt.

Andrew came to me the next day in great excitement.

‘They’ve called a meeting at the Opera House to-night, Captain! Maybe we won’t get our million after all.’

Alas, so it proved. The meeting had been convened by Bolsheviks sent from Moscow to secure Blago’s gold. Their impassioned rhetoric worked wonders. Tears rolled down the cheeks of those who crowded the theatre. The next day, the remaining reserves were loaded on board a special train made from the last of the wagons-lits and a few armoured cars:

A commission composed of ten citizens of Blago boarded the train amid the frenzied cheers and farewells of the people. Everyone wept. Who cared for tomorrow? This was a great, magnanimous gesture, a gift to Mother Russia, an offering to Moscow, food for patriots, food for Communism, food for Freedom!

Ten days later, the ragged, hungry, disgruntled Commissars returned in a lousy box car. They had been thrown out by the Moscow Reds on their arrival, told to beat it. They were fools and not wanted!

The gold vanished into the maw of Red Russia.

In a final flourish, the commissars gave Frank and Andrew a cheque for $29,000 for past services. It bounced. Frank and Andrew gave up the idea of dealing with the Soviets. They crossed the Amur River, never to return.[23]

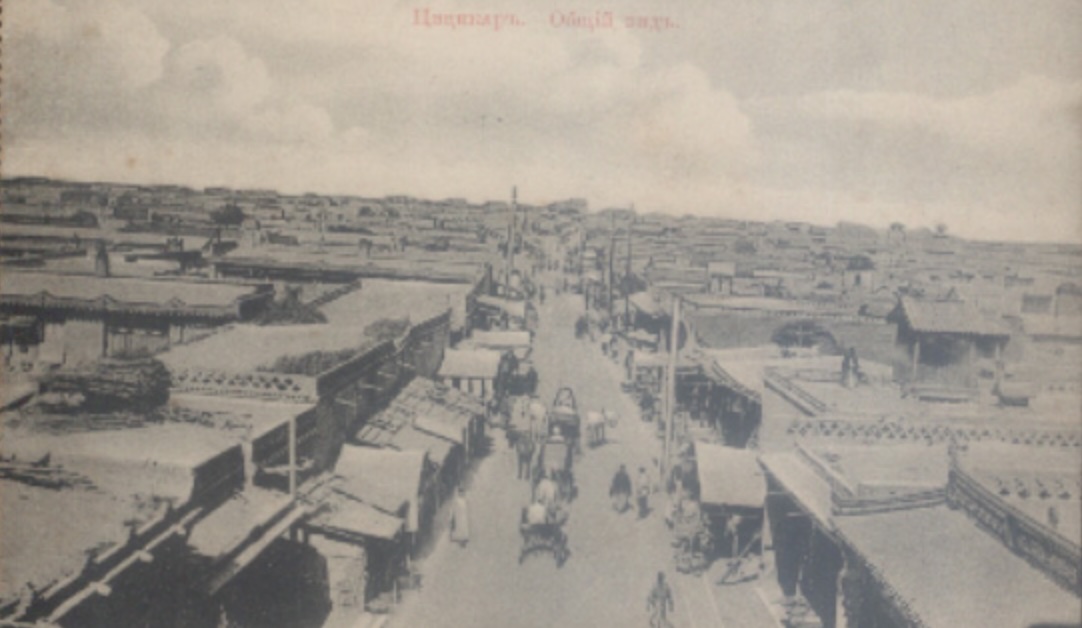

To Sichuan (1921 – 1922)

Their first objective was the city of Qiqihar (‘Tsitsihar’), a journey of some three hundred miles. Taking their Chandler, they followed cart tracks packed into the snow, travelling at around thirty miles an hour, in the company of a Chinese comprador, ‘a sort of interpreter – head office – generally handy man,’ and a Russian driver who swore he could reach their destination blindfold. They carried with them $200,000 in gold, as Frank refused to pay the ten per cent transfer fee which the Chinese banks had demanded.

For protection against bandits, they took two rifles, three revolvers and an automatic. For an extra insurance, they also stopped at a Chinese temple and paid three silver dollars to an old priest, who said he would intercede for them. He did so, and a hundred yards down the road, the car blew a tyre. When the comprador raced back to the temple to demand a refund, he found its door locked and the priest unobtainable.

They crossed the Lesser Khingan mountains (Xiao Hinggan Ling) and, sliding and skidding, descended to the Manchurian plain. The cold was intense. There were few travellers. Whenever any approached, Frank and Andrew stopped to prepare their defences, in case they were outlaws. When they reached the first town of consequence, ‘Mergen’ (possibly Nenjiang City), they were received with pealing bells and men running in all directions, shouting and gesticulating. This was not a welcome. The next town was being looted by bandits. To affect a rescue, Frank offered to escort the town’s militia in his car:

The comprador shook his head. ‘No, master,’ he said. ‘No! No! Stay here! No can do!’

He went on to explain, in a torrent of pidgin English, that, while Mergen might arm, her citizens must not go to their neighbours’ rescue. Such an attack against the Hun-Huntzes would be considered unprovoked, and retaliation would be swift and merciless, immediate, dreadful, complete … In China, the comprador said, it is a case of each town for itself, each village for itself, each man for himself!

… In the morning we saw the bandits crossing the plain, moving away from the scene of their crime with loaded pack animals and carts … By a curious mental twist [the Chinese] were unable to see the wisdom of cohesive autonomy, a China united, solidified. They were victims of an apparently deliberate stupidity, a weakness, a fallacious belief that has defeated them for hundreds of years, and in all probability will defeat them for hundreds of years to come.

From Mergen, the journey to Qiqihar was one hundred and fifty miles. There was just one road, and the chauffeur was adamant it could not be missed. But he was wrong, as became manifest when, after a bitter night, the sun appeared to be rising in the west. They were headed north, and they were two hundred and fifty miles off course. There remained just a few gallons of petrol. As Frank guarded the gold, Andrew and the comprador went in search of help. They returned with a cart, and a shepherd, who had never before seen a white man, or an automobile, and had never heard of Qiqihar, or Blago, even of Harbin.

Frank claims he hired the cart for luggage and travelled on foot. It was, he said, preferable to riding in a waggon with octagonal wheels. Qiqihar was reached after eight days, and immediately the chauffeur was sent back with petrol to collect the Chandler. Frank and Andrew visited the city governor.

We found him very civil. He questioned us at length concerning our activities in Blago, and, when I told him of the Hun-Huntzes’ attack on my barges, the theft of my clothes and the beating I had received, he presented me with a cheque for a thousand dollars to cover the damages!

It was not, I discovered, an act of courtesy. He was not at all sorry for me, nor had his heart been rung by the story of my tarpaulin suit and my terrible hat. He was afraid I might go to Peking to make a complaint; and, since a year and a half ago, I had been robbed in his province, he was taking no chances of reprimand.

Happily, the railway station was just fifteen miles away. Andrew returned to Blago and Frank proceeded to his family in Shanghai. [24]

There, the change in scene inspired his weaker spirits. He was surrounded by successful entrepreneurs and had $300,000 in his bank account. Yet, within three months, he confessed, ‘the jaundiced, yellow-eyed capitalists of Shanghai had all of my money, and I was rich only in experience.’ Extravagant living, a collapse in the value of the tael and, not for the last time, some ill-judged investments, did for him. Carina, Pepita and a second daughter, Pamela, returned to England. Depression threatened. Then a thought occurred:

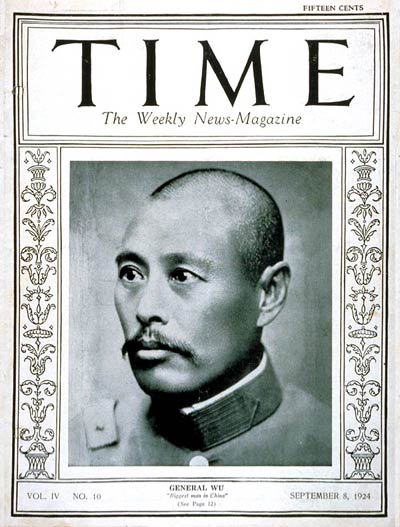

All China was fighting. It seemed to be a most profitable business. I knew how to make and use guns. Why not profit by my knowledge? … I set out to look for a War Lord whom I might serve and from whom I might be able to extract sixty thousand dollars in six months![25]

Reasoning that the roads were bad, the most effective form of transport a coolie’s back, and that the Chinese were not easily disturbed by rifle fire, Frank decided to adapt the Stokes mortar he had used at Gallipoli. He made it easy to manufacture, and designed fish-tailed shells with wings and simplified fuses, and a range of at least a mile. Satisfied that they ‘made a lot of smoke and noise on explosion,’ he headed for Wuhan (‘Hankow’), the headquarters of Wu Pei-fu, ‘a War Lord after my own fancy – a man of great personal courage, integrity, and ambition, a popular hero, respected, feared and obeyed by his troops.’[26]

At the time, Wu controlled much of central China. Experience of the Bolsheviks persuaded Frank that he needed ‘a sharp fellow’ to guide his approach. He found a smooth-tongued intermediary, the son of an Englishman and a Chinese amah, ‘who combined the bad qualities of both races.’ An interview was arranged.

We met in his Yamen in the outskirts of Hankow; and, there, in his courtyard, in the presence of his staff and a motley group of soldiers, I displayed my gun and explained why it was particularly suited to his needs. It was all I could do to prevent him from firing the mortar there and then.

‘Shoot ‘em over the town,’ he said, ‘and let’s see how they go!’

I was able to prevent this unnecessary massacre of non-combatants only after the most diplomatic arguments and polite subterfuges. I believe Wu Pei-fu thought I had a weak stomach. He could not understand my reluctance to destroy a few houses, a few citizens of Hankow. He regarded me with an enigmatic expression, a deliberate appraisal of what he probably considered my squeamishness. Then he dismissed me, turning on his heel with a characteristic, quick salute.

Despite this inauspicious beginning, Frank persisted. For a month, negotiations languished until he learned that his intermediary had quoted double his price, in spite of being promised a generous commission. He concluded,

A simple business transaction is beyond the power of the average Chinaman. There must be bargaining, bickering, retreat and advance, threat and cajoling, before a price can be arrived at and a contract arranged for. A direct, unequivocal statement of fact is offensive to the Chinese. They recoil before the sort of frankness we consider essential in business.

My interpreter could not understand my impatience. He was out to make money at my expense, and the process – to be enjoyable – must be lengthy. Otherwise, why go to the trouble of deceiving me?

The intermediary next proposed that they involve Wu’s ‘blood brother’, an ex-governor of Henan Province (‘Honan’), as a second agent. Frank agreed. The following afternoon a limousine stopped at his house and from it emerged ‘a most magnificent Chinaman’. For an hour they talked. Then the ex-governor laid his cards on the table. He required a commission of $25,000. Realising that, at this rate, he would be doing the work while others collected the profit, Frank decided to forego his services.[27]

(There was an entertaining sequel to this encounter. A year later, Frank was in Wuhan and called at the intermediary’s house. The door was opened by his ‘Number One boy’, a slim fellow in servant’s clothes. Frank immediately recognised him as the ex-governor. ‘With many self-conscious titters.’ he confessed he had received five dollars for his earlier performance.)

The lack of progress was pressuring Frank’s optimism when, one day, a stranger called at his door. Proffering his card, he announced he was from Sichuan, sent by its governor, Yang Sen. ‘News travels fast in China,’ he said. ‘We in Szechwan know you have an excellent gun.’ Yang Sen’s headquarters were at Chongqing (‘Chungking’), five hundred miles up the Yangtze. The customs service was on Frank’s tail and getting there would be hazardous. Frank asked for $3,000 up front and received it. He made his preparations.

A friendly Scots skipper was found, who disguised the gun as a section of propeller shaft. Fifty shells were passed off as engine spares, and Frank and his interpreter headed towards the Yangtze gorges. Three hundred miles upstream of Wanxian (‘Wanhsien’), they reached their destination.

Disembarking to a fanfare of trumpets, a roll of drums and an exchange of salutes, Frank was carried up the steep riverside steps in a palanquin by four brilliantly uniformed bearers. Lighting a cigar, he says he blew smoke wreaths about his head and dreamt of Tiberius Maximus on a triumphal parade. Over dinner, he was lauded as a hero, the greatest gun-maker in the world, the saviour of Sichuan. Yang-sen appointed him Director of Munitions:

Before I could gather myself to express my appreciation, he went on to say that I might choose three of the prettiest dancers in Chungking to take with me to my newest residence.

Whereupon a whole bevy of sing-song girls entered the room behind lacquered screens, and turning their face to the wall, made the horrible noises which pass for love songs in China.

This was true hospitality! Since I spoke no Chinese, I signified my delight by fishing around in [my] soup, rescuing [a] mournful slug and awarding it to the prettiest girl.[28]

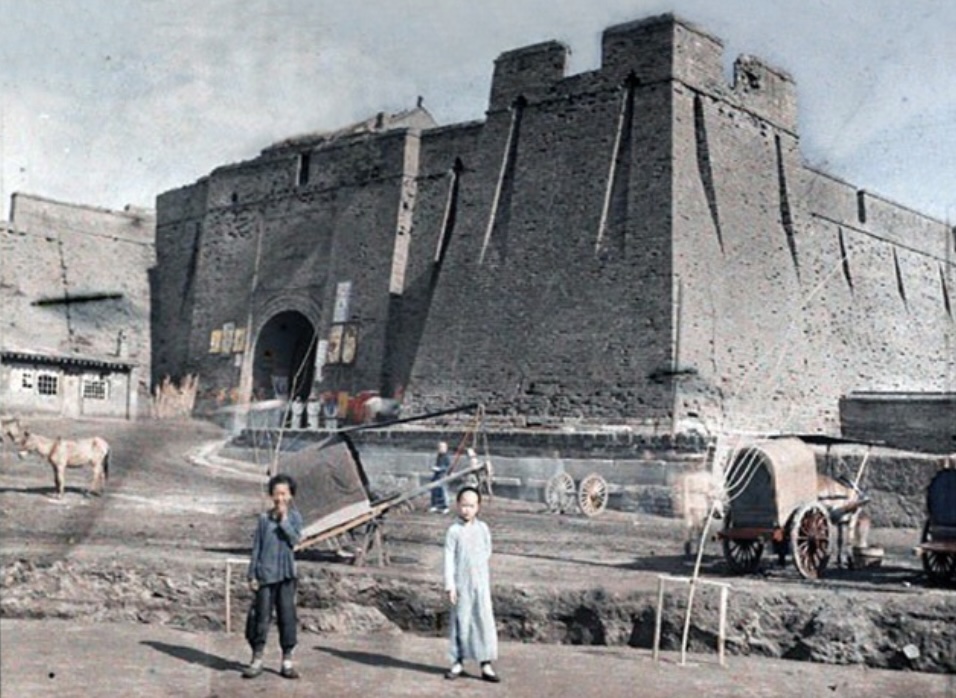

The following morning, Frank was taken twelve miles upstream to the Mint. Surrounded by a rampart a hundred feet above the river, it was built like a fortified town. At its centre was an arsenal and, beside it, a large lake in the centre of which an old pagoda was ‘reflected in quaint loveliness.’ This became Frank’s residence. His first act was to construct a second bridge from it across the lake, in case a rapid exit became necessary.

The arsenal was equipped with some old lathes and a small foundry. Its director informed Frank there were seven hundred and fifty employees, which appeared an over-estimate. In fact, there were just two hundred and fifty. The imaginary payroll of the remainder was for the pocket of the director and his associates. Frank informed Yang Sen, but he was told not to worry.

It is the custom in China [he explained] – pay no attention to such little discrepancies, Captain Sutton. Wang is an old friend of mine. An excellent man. An honest and upright man. Think no more of it![29]

Within ten days, sufficient shells had been manufactured to permit an initial test of Frank’s weapon. It was a success, and he was paid a starting fee of $50,000. In addition, he received a monthly salary of $20,000. He was ‘struggling with ignorant, treacherous workmen, [so] that a Chinese General might defeat an army I knew nothing about, for a cause in which I had no interest,’ but appearances were set fair. [30]

The situation, however, was not as stable as Frank would have wished. Yang Sen commanded just one of three armies in Sichuan. It was the largest, but General Sun Chuan-fang, at Wanxian with another, had proclaimed himself ‘Commander-in-Chief of the Upper Yangtze’, and in the hills at Chengdu, General Ma Jui (‘Ma-Yu-Ching’) was ready to descend at any time.

This, in due course, is what happened. Yang Sen took his army downriver to discipline Sun, leaving Frank, with two hundred troops, in charge of the Mint. He prepared its defences, marking the valleys around with white posts to indicate the ranges and establishing emplacements on tombs in the hills beyond.

Soon rumours emerged of movements in the north and, fearing the worst, Frank took an interpreter ahead to assess the situation.

[The] interpreter tried desperately to please me. His English was weird and wonderful; his tongue tripped over consonants and twisted itself helplessly around vowels. But he was a plucky little coward, engaged in a ceaseless battle with his own timidities, conquering by sheer force of will.

On the third day, they descried from the summit of a pass an army of forty thousand, ‘an endless stream of men, horses, carts, equipment,’ advancing towards Chongqing. Yang Sen’s garrison decided that, under the circumstances, discretion was the better part of valour. In Frank’s words, ‘They beat it to the hills, where they underwent the customary lightning-quick transformation into peaceful farmers.’ Only two hundred remained.

Immediately, General Ma sent fifteen thousand men to invest the Mint. They employed three batteries of Krupp field guns, firing shrapnel from a position rather beyond the range of Frank’s mortars. The fighting went on for eight days.

The terrified interpreter followed Frank everywhere, his progress ‘a series of spasmodic jerks … his falsetto stammer echoing my commands like the piping of a spirit self, a disembodied alter ego issuing orders from the ether.’ Yet, amazingly, even as the Mint suffered persistent shelling and sniper fire, work on the farms beyond its walls went on:

Fighting or no fighting, shells or no shells, the Szechuan farmer waded out into the paddy fields … He knew that, when our little struggle was over and forgotten, his rice fields would still be there … that planting and garnering went on for ever.

On the eighth day, Frank was summoned, under safe conduct, to General Ma’s camp.

[He] awaited me in a large room lighted by oil lamps that swung down from the beamed ceiling. He was seated alone at a table, his face in shadow … He rose and bowed to me across the table. I didn’t like the look of the five men standing to one side with fixed bayonets. I said to my interpreter:

‘Tell old whiskers here that it is not customary in my country to have an armed guard present during a peace parley.’

The terrified fellow held up both hands imploringly.

‘Don’t make him angry, please! We are in great danger! Please, sir, don’t make the General angry!’

… The General smiled and gave the order … One of the men, in complying, let his rifle fall with a crash to the floor. I turned my head quickly and heard the interpreter gasp a sharp, warning intake of breath. I jerked my head around and found myself looking into the business end of a Mauser pistol.

… I reached for my own pistol, ducked my head to one side, as a bullet whizzed past my ear. I pulled my Colt .45 and, as [Ma] fired a second time, holding my gun horizontally, I got him! There was no time for vertical sighting. I plugged him neatly between the second and third buttons of his tunic, and he fell forward, his head hitting the table with a crash, his pistol spinning out of his hand.

In the ensuing melée, the guards were overly occupied in unfixing their bayonets, and Frank was able to get away. (The interpreter, sadly, was not so lucky. He received a bullet in the head, and fell at Frank’s feet, ‘curled up in his agony like a dying dog.’). Determined retaliatory action was sure to follow, and Yang Sen was too far away to provide relief. Frank evacuated. The arsenal’s mortars, ammunition and other equipment were pitched into the Yangtze and its director was persuaded, at the point of a pistol, to surrender six of the ten boxes of silver that represented the balance of Frank’s pay.

With these, Frank escaped to Wanxian on board the Jardine steamer Fuh Wo. On her voyage she came under constant fire, which Frank, the crew and other passengers returned from the bridge, the only armoured part of her superstructure. When they reached their destination, the steamer’s funnels had been so perforated they looked ‘like great pepper boxes’. [31]

To Yang Sen Frank made his apologies, importuning him to consider him still his faithful friend. Yang thanked him for his service and asked him to return to Wuhan, to enlist the support of his friend Wu Pei-fu. But Wu remained uninterested, and Frank returned to Shanghai. There, on the advice of Bertram Giles, later consul general at Nanking, he attempted to sell his services to Sun Yat-sen, but Sun declined his offer, claiming that he preferred counting votes in ballot boxes to corpses on battlefields. When Frank warned that, in his stead, he would turn to the ‘Old Marshal’, Chang Tso-lin (Zhang Zuolin), Sun’s principal opponent in the north, Sun agreed that, in Frank’s place, he would do the same:

The Marshal and myself are at opposite poles. I am a man of peace and he is a man of war. But in our different ways we both work for the unity and freedom of our country. At present our quarrel is with Britain but you are not a dangerous foe. The real peril will come from the north, from Russia and Japan. Their time is not yet, but it will come soon and then the first to face them will be Manchuria. Go to the ‘Old Tiger’ and, when you see him, you may give him my good wishes. He will understand.[32]

North China (1922-1926)

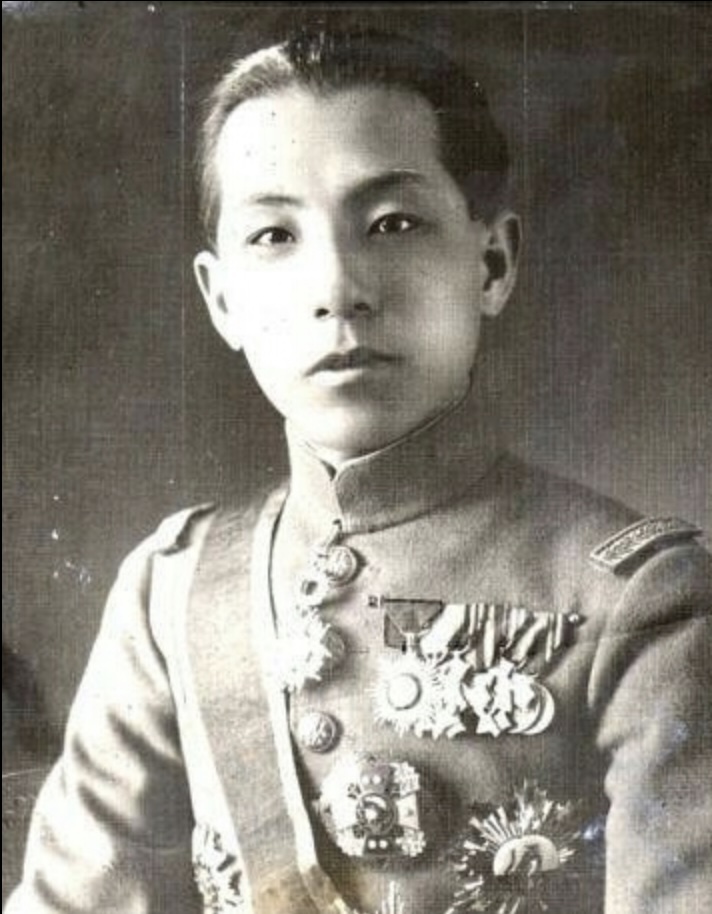

Frank travelled to Shenyang (‘Mukden’), taking a mortar and some ammunition, which he had earlier secreted away in Shanghai. Instead of receiving his hoped-for welcome, however, he was told to go away. Immediately, he stormed into the Foreign Affairs building where, in one of the corridors, he collided with a diminutive figure in uniform. Picking himself from the floor, the Chinaman realised who Frank must be: the man who, as he put it, ‘had come to assassinate his father.’

An interpreter was fetched and, in the ensuing conversation, Chang Hsueh-liang (Zhang Xueliang) summarised the reports he had received: that Frank had come from Siberia and might be a Bolshevik agent; that he had won a battle at Chongqing by use of poison gas and black magic; that he had arranged the meeting with General Ma and had then shot him in the back, under a flag of truce.

These reports notwithstanding, he was enthused by their encounter. He suggested that an ex-tempore demonstration of Sutton’s wares might win his father over. The occasion chosen was one of those parade ground reviews of which the ‘Old Marshal’, something of a martinet, was very fond. As it drew to its climax, Frank drove into sight in a Model T Ford equipped with a mortar. There was a commotion. An ADC was sent to establish what he was doing. Frank claimed his weapon would make Chang ruler over China and, as the Old Marshal wondered how to respond, his son persuaded him there was nothing to be lost by giving it a try.

A space was cleared, and Frank fired four shells. They exploded most satisfactorily, but a fifth misfired. As Frank was dealing with it, a horseman galloped up and demanded why he had stopped. Frank responded that there was no more ammunition, whereupon he was told the Marshal wanted a demonstration of several hundred rounds. He was given three weeks to get everything together.

That demonstration was a triumph and soon Frank was discussing terms. Then he was told that one of his subordinates from the Mint was offering a cheaper solution. Frank proposed a duel in which they would be placed a thousand yards apart and would shoot mortars at each other to the death. He passed a sleepless night fitting fins to his shells to improve their accuracy, but was relieved to learn the next morning that his challenger had fled to Harbin.

There then followed a hiatus of several weeks in which both Changs became mysteriously inaccessible. Finally, Andrew the Greek reappeared out of left field and revealed to Frank that he was being double-crossed. Chinese engineers had been copying his design and had mastered all but his patented fuse. The plan, clearly, was to cut Frank out of the deal altogether.

In response, Frank announced he would embark some dangerous development work. He closed his workshop to all visitors. A week later, he emerged with a blackened face and three-inch gash across his cheek. He announced he needed time off to recover from his injury. But the interest of the Chinese was aroused, particularly when they found the key to the workshop on the seat of Frank’s car …

Two days later, Frank was summoned before the Changs, father and son. Chang Hsueh-liang announced that, in a most unfortunate accident, their most trusted technical adviser had been killed. Since the post of Master General of Ordinance had become vacant, it was being offered to the Englishman. Frank received an up-front payment of £15,000.[33]

The task which he faced was daunting. The Changs had spent nearly £100,000,000 on their arsenal, but the more they invested, the less it produced. In scale it dwarfed the Mint, with tens of thousands of employees, much muddle, inefficiency and corruption. Frank estimated it was costing three times as much as it should, and was producing at just a fifth of its potential.

It was not difficult to see why. During his initial conducted tour, Frank was mystified by the sound of activity coming from within, and the absence of output. When passing an apparently deserted machine shop, he briefly eluded his escort. Inside he found a spectacled clerk banging the end of an oil drum with a spanner. Taking him by the scruff of the neck, Frank confronted Chang Hsueh-liang with what he had discovered. The Young Marshal was quite unfazed. He was, he said, quite aware of how badly the arsenal was run, but his father had promised to staff it with Chinese only and he could not afford to lose face. Besides, the clerk was only doing what he was told. He advised Frank that, since his success depended on winning the support of the employees, rather than on beheading them, he should do his best to appear impressed. Then he would be appointed.[34]

From these unpropitious beginnings, Frank gradually turned the operation around, by concentrating production on small arms and only later upgrading to three- and then eight-inch mortars and simple artillery. Other, more complicated equipment was smuggled into Manchuria with the assistance of General Chang Tsung-chang (Zhang Zongchang), an associate of the Old Marshal with a power base in Shandong.[35]

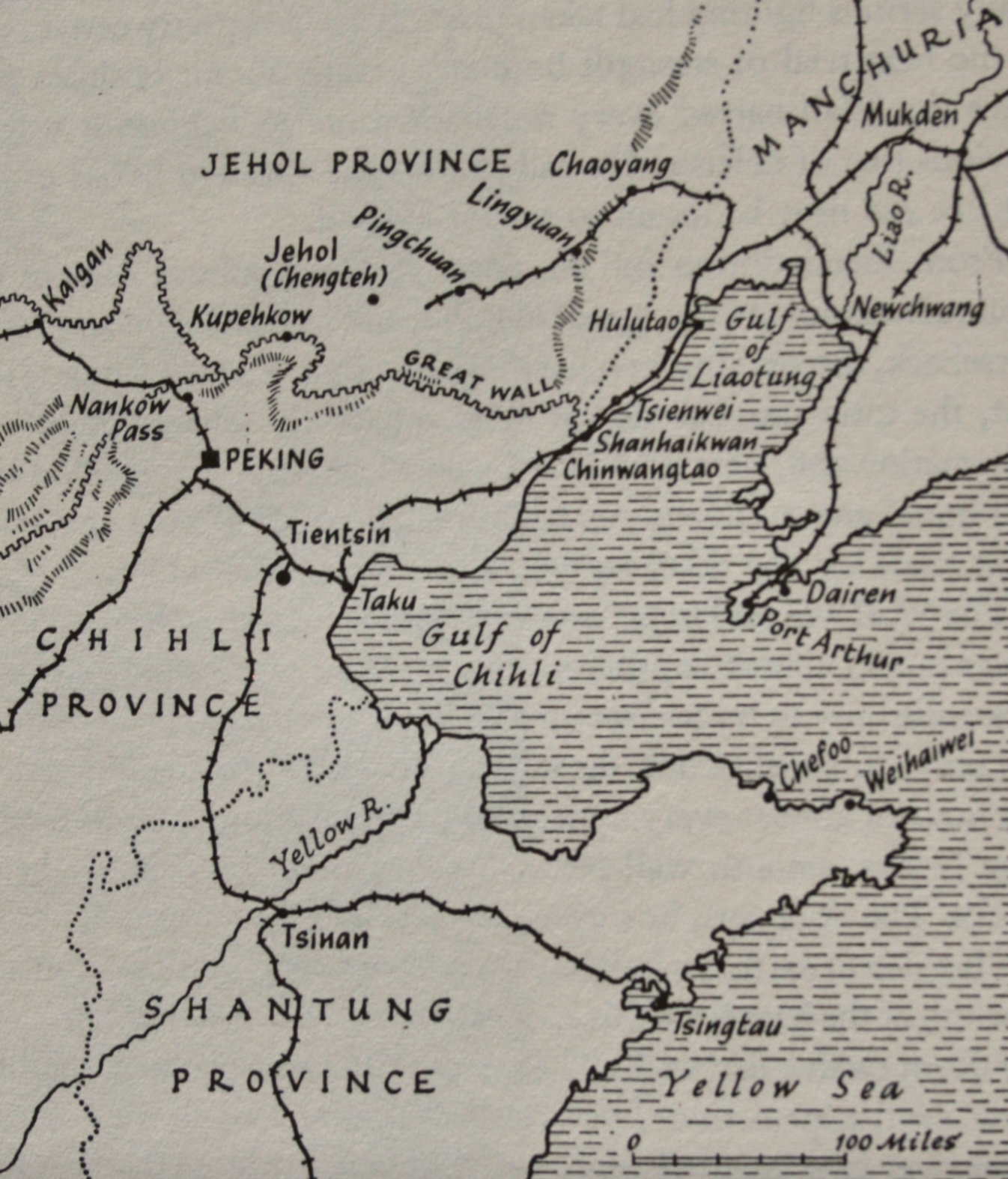

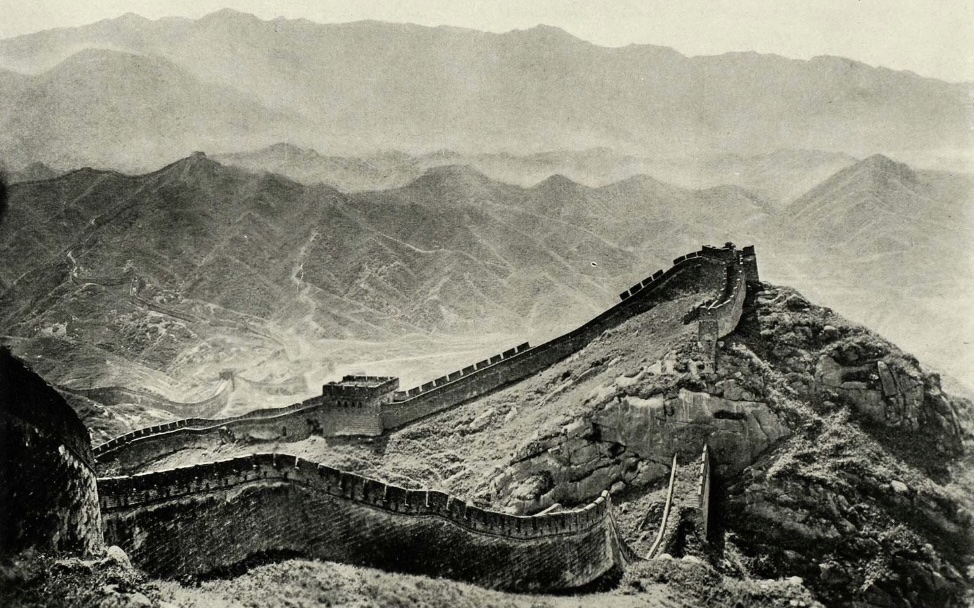

There was some difficulty when some Germans attempted to muscle in on the operation and Frank was overly forthright in criticising their proposals. Chang Tso-lin was so upset by his effrontery that Frank chose to disappear for a month, to practice his golf. He used the occasion to investigate where the Great Wall might be most exposed to assault and decided that, instead of the traditional points at Nankow or Shanhaiguan, where it was joined by the railway, it would be better to concentrate an attack on Kupehkow. There, the wall crossed the Pei Ho River in a series of zig zags almost designed to expose its defenders to enfilading fire.

He rushed to Shenyang to put the Old Marshal straight. Such was his enthusiasm that he forgot to dispose of his pistol before entering the great man’s presence. Immediately he found two heavy-calibre Mausers levelled at his back. Nevertheless, the encounter broke the ice. Chang was not yet ready to go onto the offensive, but Frank was told to submit a detailed plan.[36]

As it turned out, 1923 was quiet, as the three armies in the south were too occupied by internecine strife to strike north. The Kuomintang under Sun Yat-sen were busy negotiating a coalition with the Soviet Comintern, while the Great Kanto earthquake was absorbing the attention of the Japanese. This suited Chang as, although his supplies of equipment were growing, his men were poorly trained.

This was apparent even in the summer of 1924, when Frank witnessed a drill in Shandong, in which the guns were in such poor condition that most either misfired or fired not at all. Discipline was harsh. On one occasion, when Frank drew Chang Tsung-chang’s attention to a rusted breech block, he watched him skewer the responsible officer to the gun’s wheel with his sword. The officer was spared death only because Frank fired the artillery piece next door to distract Chang’s attention. Even so, the general declared that, at the next trial, in three days, the officers responsible for their guns would be immediately executed if any failed to fire.

Frank was too nervous of the outcome to attend the tests himself, but he joined the general at dinner afterwards. At it, he was shown much favour, and he began to hope that developments had been better than feared. In fact, just one gun had failed, as became clear at the end of the meal when an officer was decapitated at Frank’s feet. He was sick on the spot.[37]

Hostilities between the warlords finally erupted, in October 1924, as a result of a squabble between the Old Marshal and Wu Pei-fu over who should receive the rake-off from an opium smuggling operation near Shanghai. When the president in Peking, Tsao Kun (Cao Kun), sided with one claimant, Chang told him not to interfere. Wu rushed to Tsao’s protection, concentrating his troops and navy at Shanhaiguan.

As Chang slowly advanced from Shenyang, with a force of some 150,000, Frank begged to be permitted to attack Kupehkow. Chang refused him, ordering him instead to bring south the supply of arms for which he was responsible. Thus, Frank and Andrew found themselves directing a fully laden ammunition train alongside the Gulf of Liaodong. Andrew was on the footplate, Frank in the guard’s van.

At Huludao, and again at Tsienwei, the train came under fire from Wu’s cruisers offshore. At Huludao, the driver was dissuaded from dismounting only when his stoker, who drew a knife on Andrew, received a hand grenade in his breeches and was kicked onto the tracks. At Tsienwei, there was a desperate moment when the driver accidentally knocked the vacuum brake, and the train halted on a bridge spanning a river. As shells landed about them, the crew managed to restart it, and they got away. Smiling, Andrew later remarked that, in fact, the bridge had been the best place to stop. Its elevation robbed the crew of all means of escape.

Frank was now given permission to prepare his attack on Kupehkow. He travelled to Jehol to collect his troops, only to find his second-in-command engaged in an opium debauch which rendered him incapable of command. Others, seeing the balance of demand and supply temporarily upset by the presence in the city of six thousand soldiers, had lost interest in the war and, instead, were engaged in the lucrative brothel business.

Before long, however, Frank had licked them into shape. His mortars sent Kupehkow’s defenders scattering into the towers atop the wall or onto the ground behind where, as a result of the wall’s design, they remained horribly exposed. Opposition quickly ceased and Frank’s men carried the day by the simple expedient of opening the gate. The road to Peking was open.

Sadly, visions of a triumphant entry immediately evaporated. Frank was told to report to Tianjin (‘Tientsin’). Feng Yu-hsiang (Feng Yuxiang), an ally of Wu’s, but a notorious turncoat, had seen the writing on the wall, and had occupied Peking on behalf of Chang.[38]

Feng called himself the ‘Christian Emperor’, but he was no saint, and Chang protected himself by encamping some forty thousand troops in the vicinity of the capital. Frank was to keep them supplied with arms. This he did, in part, by taking a share with a Norwegian in a cargo ship and using it to ferry contraband TNT from Europe. By way of reward, Frank was raised to the rank of Major General and given a one-off payment of £20,000.[39]

He was next asked to obtain intelligence of Feng’s connections with the Russians. This he did by lavishing huge sums (including £30,000 he netted in a sweepstake on the Shanghai Champions horse race) on grand parties, at which secrets had the habit of escaping the lips of his guests. Frank learned of plot to stage an incident on the Amur River in order to force the Old Marshal to quit the city. Chang was to be assassinated as his train crossed one of the bridges on the journey north.

Chang forestalled the plot by halting in Tianjin. He kept Feng in check and waited on events. For a while, Frank moved to Harbin, extending his intelligence network beyond Manchuria into Kalgan, Feng’s home territory, where British American Tobacco had a presence. Then, back in Peking, he played the part of a spendthrift, to attract more potential informers to his circle. He even went so far as to buy control of the Baroussky Circus, which, as an investment, was a failure. The role came naturally, but it fooled no one.

One night, having escaped a contrived car accident, Frank returned to his hotel and found a message pinned to his pillow:

SUTTON – Everything you do, we know. You be careful. You draw maps, print circulars. HA! You send out, HA! HA! you die. We everyday follow you – Peking Club, every place. Car No. 48 56 of Mukden. No fear your pistol. Only air. You be good to us. Meet soon.

On another evening, a parcel delivered to the hotel gave off a muted bang and a puff of smoke as Frank opened it. Experts said that, had the detonator worked properly, it would have taken much of the foyer with him. The hotel’s proprietors were pleased when Frank retreated to Tianjin.

In its British concession he should have been safe, but the threats kept coming. Frank armed his car with a specially adapted Mauser attached to a mounting by the windscreen. The manner of his driving – always unnerving – became positively hair-raising and, as his behaviour became more erratic, his friends became less accommodating. Few were sorry when he returned to Shenyang.

Even there, he was unsafe. The Soviets had flooded Manchuria with agents, as Frank discovered when two broke into his office and, at the point of a gun, demanded that he hand over his secrets. In this instance, Frank bluffed them by declaring that everything had already been delivered to the Marshal. The agents took to their heels, but henceforth Frank went everywhere with two loaded pistols.

In this period, Frank grew closer to the Old Marshal and his son. Indeed, he and Chang Hsueh-liang became firm friends. Frequently, they played poker, and often Frank won. The Old Marshal, unfortunately, was not a man of honour. He offered out IOUs, but they were illusory. On the first occasion on which Frank tried to encash one at the Treasury, he was greeted with amazement and sent packing. Frank complained to Chang Hsueh-liang, who promised to have a word. Opportunistically, Frank then bought the Marshal’s obligations to all the other members of the club at fifty per cent of their value. They were honoured in full, but there is every reason to believe this was a unique event.[40]

1925 proved to be a difficult year. At its start, Sun Yat-sen travelled to Peking. Fearing communist success, he hoped to broker a peace between the northern warlords and utilise them as a bulwark against Russia. He failed, however, and in March, he died a broken man. Feng Yu-hsiang and the Soviets agreed a pact of mutual assistance.

Feng also allied himself with Sun Chuan-fang who, having triumphed over Yang Sen in Sichuan, had risen in the ranks of the so-called Zhili clique of warlords to become governor in Zhejiang (‘Chekiang’). In October, Sun struck against Chang Tso-lin and drove him out of the northern part of his province. He then prepared an offensive up the Grand Canal to turn Chang Tso-lin’s flank. Chang retreated from Jiangsu province and fell back on Tianjin. Frank begged for an active command but was told that appointing a foreigner at such a time would sow discontent. He returned to Shenyang.

News from the front remained poor. Chang Tsung-chang attempted to support the Marshal from Shandong but he was immobilised by a mutiny fostered by Russian fifth columnists. Then, Kuo Sung-lin, the general protecting the passage at Shanhaiguan, defected to Feng, who launched a drive against the Marshal in Manchuria.

The effort failed. The Young Marshal launched a strike against Kuo and routed him on the Liao River. Feng, whose reputation was already suffering from defections in his army and deaths among his wounded, for lack of medical care, retired to Moscow to ‘study communism’. For now, Chang Tso-lin was secure.[41]

All was not well with his son, however. At the Liao River, he had contracted severe influenza. He attempted to alleviate its symptoms with opium. This developed into an addiction which threatened to destroy the kudos which his victory had bestowed. Frank came to his help, using his friendship to re-energise his younger charge and, at the same time, to quash rumours about his condition. It was to prove his last major service. Amidst the changes taking place in China, Frank’s position was becoming increasingly anomalous. The growth of nationalism meant resistance to his influence was bound to grow even among the Changs’ supporters.[42]

The English in the concessions also frowned upon Frank’s activities, although some enjoyed the amusing side of his personality. There was, for instance, a dinner for the Old Comrades Association of Tianjin, at which General Sutton arrived wearing his uniform and medals and was asked, since it was a British dinner, at least to place his M.C. before the others.[43]

Others of greater influence in the community were less relaxed. To those, such as Colonel L’Estrange Malone MP, who regarded Chiang Kai-shek with favour, the idea that the arsenal of his main challenger was being managed by a former British officer was something absolutely to be condemned. One evening Sir Harry Fox, the Commercial Counsellor in Peking, was heard to comment, in Frank’s hearing, that he did not care to drink in the company of gun runners. (Frank yanked him out of his chair and told him to wait outside until he had finished.)

The truth was that the days of the warlords were ending. By the end of 1926, Chiang Kai-shek controlled all of China south of the Yangtze. In the north, the Old Marshal was master. If ever they came to blows, they would achieve little except provide Russia or Japan with an opportunity to clear up the pieces.

Frank packed his bags. He was, after all, a very wealthy man. It was time for him to return to the company of his family.

Final Years (1927-1944)

In early 1927, he sailed to Vancouver, where he embarked on an investing spree of epic proportions in real estate and railways. As the cracks began to form (Frank’s timing, as ever, was poor), he heard of the assassination of Chang Tso-lin, whose armoured train was blown up by the Japanese. After the Wall Street crash, he was ruined.[44]

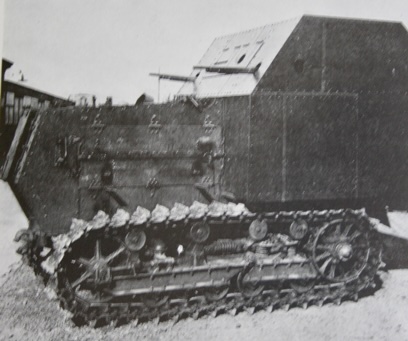

For a period, Frank sank into another severe depression but, slowly, he scrambled his way back to solvency. For a time, he earned a salary as a ring master in a wrestling hall (for this, he claimed the Baroussky Circus had been good experience). When eventually, through some fire sales, he cleared his debts, he returned to China for a last fling of the dice. His focus was the ‘Sutton Skunk’, an armoured vehicle adapted from a five-ton 1917-vintage Caterpillar tractor, which Frank equipped with twin Stokes mortars and a pair of machine guns.

He arrived in Shanghai in August 1932. By then, Manchuria had been lost to the Japanese and Chang Hsueh-liang had moved closer to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government. Whether Frank ever shipped any of his ‘Skunks’ is unclear; how well they would have served, even less so. To the Germans advising China’s military they inspired little confidence.

Having met with rejection, Frank travelled to Peking where he was warmly received by the Young Marshal. But times had changed. Chang was courted by sophisticated advisers with whom Frank was hard-pressed to compete and, anyway, he had ceded most of the decision-making to Tang Yu-lin. Described by the journalist Peter Fleming as ‘a man of exquisite iniquity’, Tang was more interested in the sale of Manchu treasures and morphine, which he manufactured in the precincts of his Jehol palace, than in fighting the Japanese.[45]

Hopes for the Skunk sank without trace. Then Frank was invited to report on the campaign for the Hearst organisation. He filed a few stories coloured with misplaced optimism. Privately, he was ‘thoroughly ashamed’ of the troops under Tang’s command. In February 1933, the Japanese cut through them like a hot knife through butter. The Young Marshal ordered the arrest of his subordinate, but he loaded 240 trucks with his collection of Manchu treasures, and decamped to Mongolia, before he could be seized. Frank’s career as a war correspondent was short-lived.[46]

In December 1936, the Young Marshal kidnapped the Nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek, in an explosive event which became known as the ‘Xi’an Incident’. Officially, he sought to force Chiang into a change of policy, prioritising resistance to the Japanese over the purging of Shaanxi’s communist ‘traitors’. No doubt, he also sought to protect his position in the command structure. There followed two weeks of negotiations, in which Zhou Enlai played a prominent role and Stalin pressed for Chiang’s release from behind the scenes. He was, he argued, the only Chinese commander then capable of containing the Japanese. Chang he was persuaded to relent. Chiang Kai-shek was released, and, in an outward show of loyalty, the Young Marshal flew with him to Nanjing. Almost immediately, he was court-martialled and placed under house arrest, first in China, later – until Chiang’s death, in 1975 – in Taiwan. He died, in Hawaii, at the age of 101, in October 2001.[47]

For Frank, the years 1934 to 1937 were spent aimlessly in Harbin and Korea, where his efforts at enterprise were defeated by the restrictive Japanese. When at last, in Seoul, they attempted to recruit him as a propagandist for their ‘Benevolent Rule’, he expressed his refusal in terms that earned him four nights in prison and expulsion to Hong Kong.

There, he found himself in more congenial company. As WWII approached, he set up a factory in Kowloon to manufacture webbing equipment. With the help of some of the workforce from his old Shenyang arsenal, who were smuggled into the Territory with the connivance of the Hong Kong Police, it was expanded to supply machine tools and shell fuses, and, by the time the Japanese invaded, Frank was again quite successful.