The Capture of Robert Knox

Knox was born in London in 1641, the son of Robert, a sea captain from Suffolk, and his wife, Abigail Bonnell:

In the time of my Childhood [he wrote] I was Cheiefely brought up under the education of my Mother, my Father generally being at Sea … She was a woman of extraordinary Piety; God was in all her thoughts as appeered by her frequent discourses, & Godly exhortations to us her Children to teach us the knowledge of God, & to love, feare & serve him in our youths …

The piety of Knox’s family colours many of the ruminations in his book, yet the sea, not the Church, was his calling:

When I was aboute 14 years of Age my father had built him a new ship … & my inclination was strongly bent for the Seas, but my father much avarce to make me a Seaman, it hapned some Sea Capts coming to see him, amounge other discourse, I standing by, asked my father if I was not to goe with him to Sea. Noe, saith my father, I intend my Sonn shall be a tradsman, they put the question to me, I answered, to goe to Sea was my whole desire, at which they soone turned my father, saying this new ship, when you have done goeing to sea, will be as good as a plentifull estate to your Sonn & it is pitty to crosse his good inclination, since commondly younge men doe best in that Calling they have most mind to be in.

Knox senior was persuaded. In December 1655, he took his son on a voyage to Fort St. George and Bengal. They returned, in July 1657, to find the East India Company’s fortunes ‘suncke & next to nothing.’ As speedily as possible, Captain Knox fitted his ship, the Anne, for a second voyage. He was just forestalled: Cromwell reconstituted the Company ‘& forbid all others.’ And so, it was in the Company’s service that, in January 1658, Knox sailed on that ‘fatall voiage in which I lost my father & my selfe, & the prime of my time for buisnesse & preferment for 23 years tell Anno 1680.’[2]

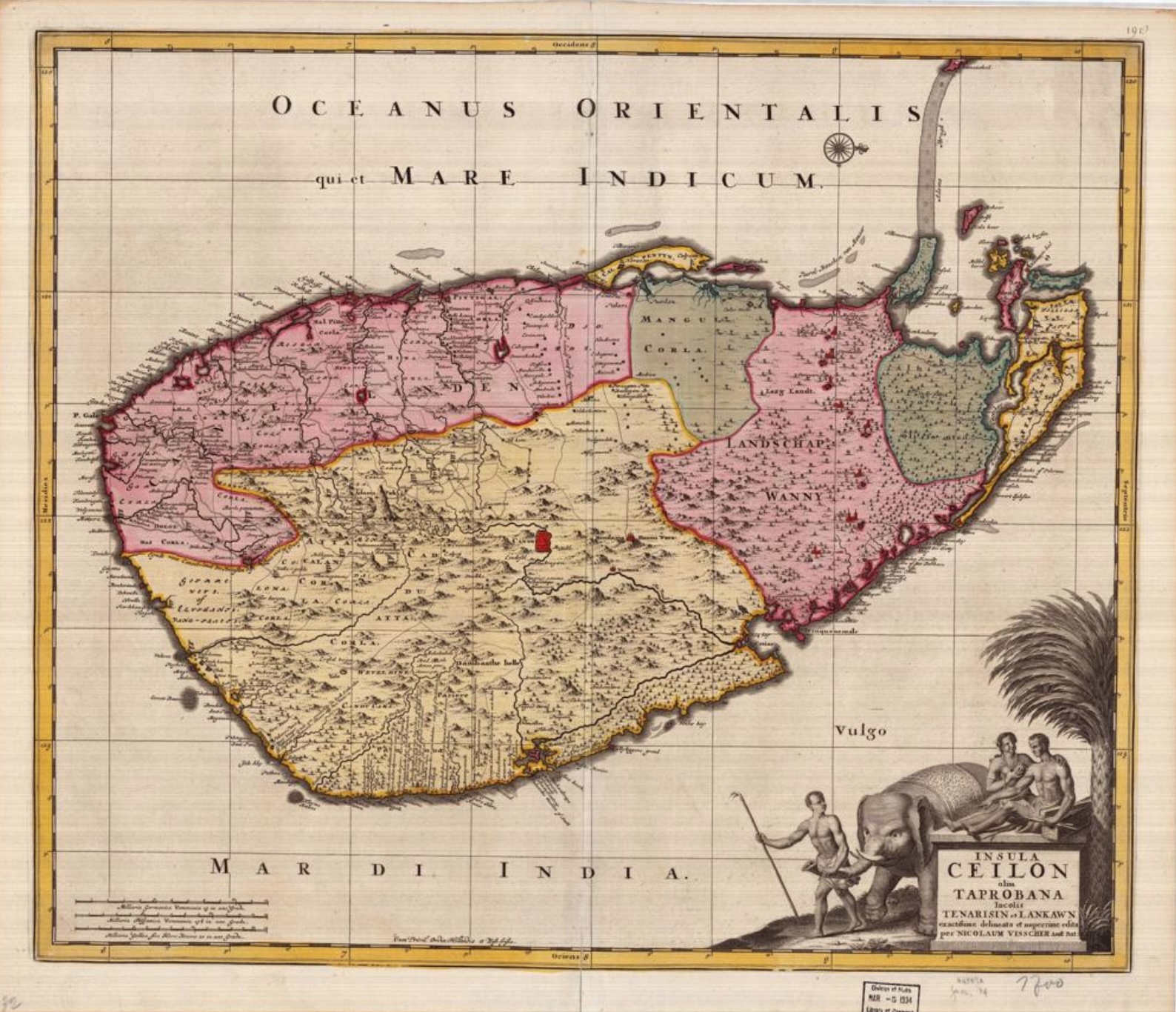

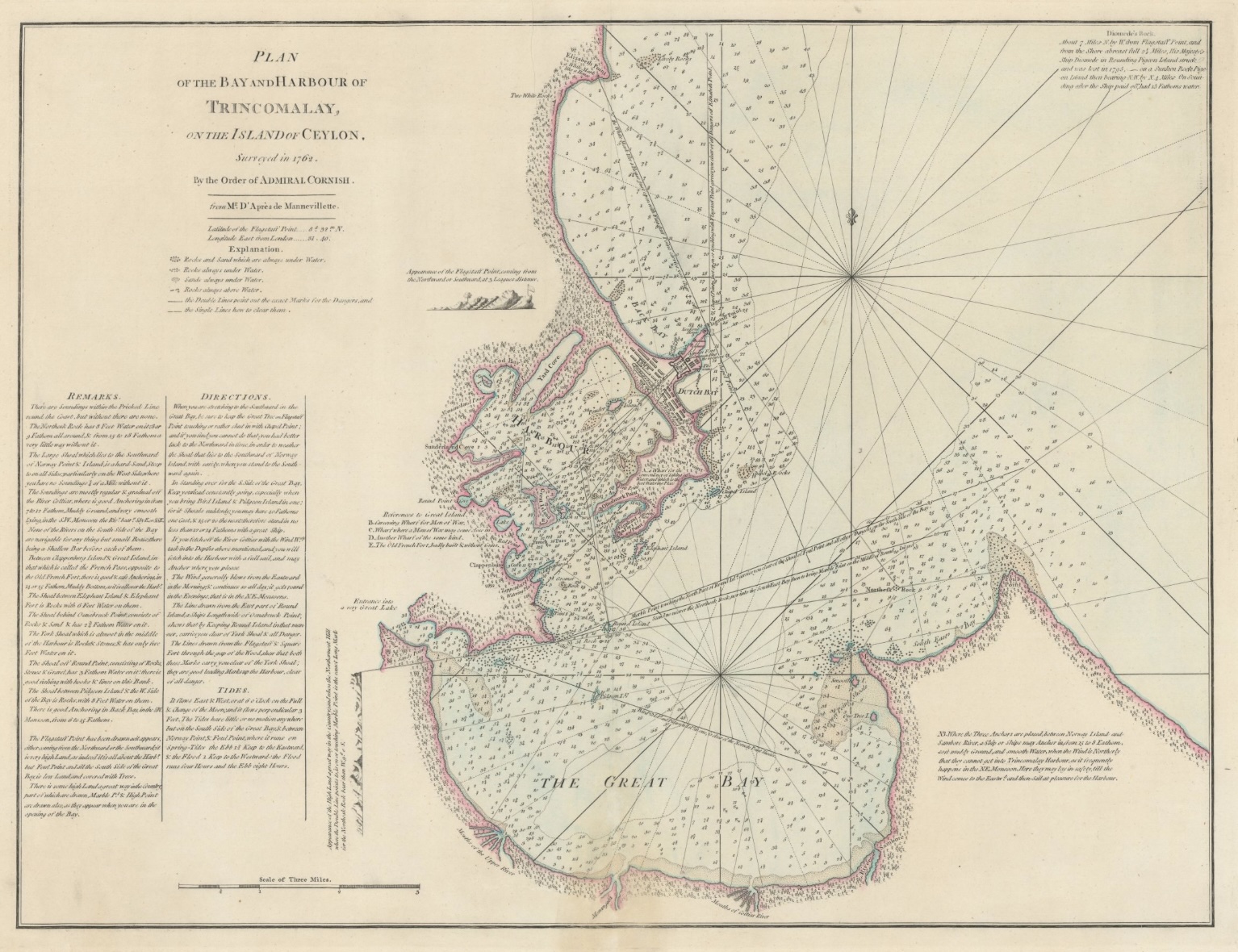

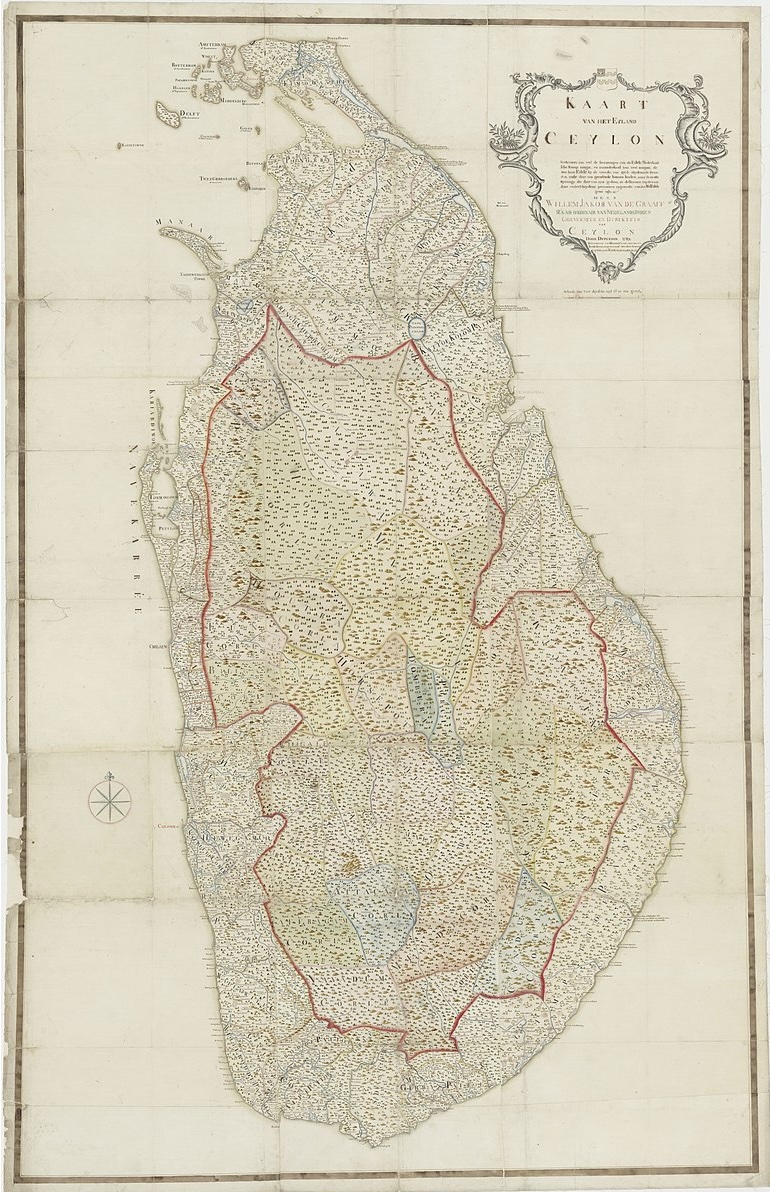

In November 1659, the Anne was dismasted in a cyclone, at Masulipatam. For her repair, she retired to Kottiyar, on Ceylon’s Trincomalee Bay. Much of Ceylon’s littoral was then controlled by the Dutch. The Kandyan king, Raja Sinha II, who ruled the hinterland, had allied with them against the Portuguese. He conceded a monopoly in spices and agreed to fund the costs of the campaign. But, by discounting the value of the trade, and inflating the campaign’s costs, the Dutch claimed they were under-compensated. Territory was seized as ‘collateral’ for what they said they were owed.[3]

Yet, the Dutch were chiefly interested in cinnamon. Trincomalee was not a producing area. It remained in Kandyan hands. It became the port through which Raja Sinha, and the English, sought to break the Dutch monopoly.

The process began in 1648, when Charles Wylde reported on Danish trade in cinnamon, betelnut and grain between Trincomalee and Metchlepatam. He wrote that in Trincomalee’s harbour ‘may ride a 1000 saile of shipps and never be discovered.’ He added that, ‘for trimeing of ships and for good tymber man never saw better in these parts, Madraspatam being but a dung hill to it.’

In January 1659, a private trader, John Hoddesdon, informed Surat that Indian merchants at Tuticorin, south of Madras, were offering the English an opportunity for establishing a factory nearby:

… they were confident from Zealone they could procure store of cinnamon to be brought in small vessells that comes from thence to their ports, the King of Zealone being much discontented with the Dutch for their false dealing after they had assisted them to take Columbo.

In response, the Company opened a trading post at Kayalpattinam (‘Caile Velha’). And, in November, following the storm, Captain Knox was instructed to load the Anne with calicoes ‘and go to Cotiar Bay, there to trade, while she lay to set her mast.’[4]

Initially, Kottiyar’s unfamiliar surroundings made the crew nervous, but their fears were allayed by the people, who ‘very kindly entertained us for our money,’ and by the local governor’s welcome. Then, on 4 April 1660, a dissava, or district governor, arrived with a small force to discover the strangers’ intentions. Captain Knox was asked ashore, but he demurred and sent his son and a merchant, John Loveland, instead. They were taken a full twelve miles inland, where the dissava’s manner appeared increasingly suspicious. Knox wrote a note warning his father ‘not to adventure himself.’ Unfortunately, it was not delivered, and, on 10 April,

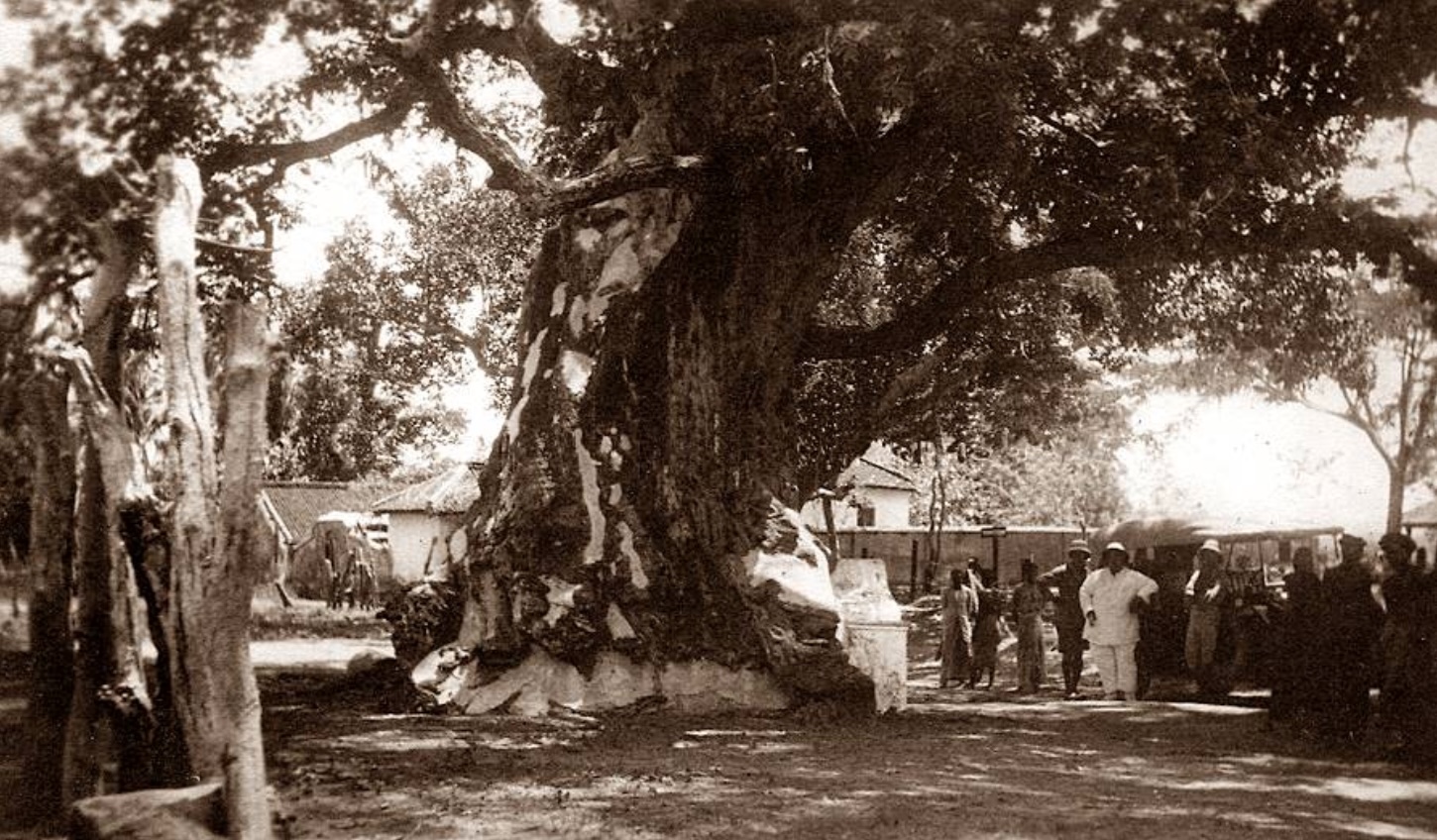

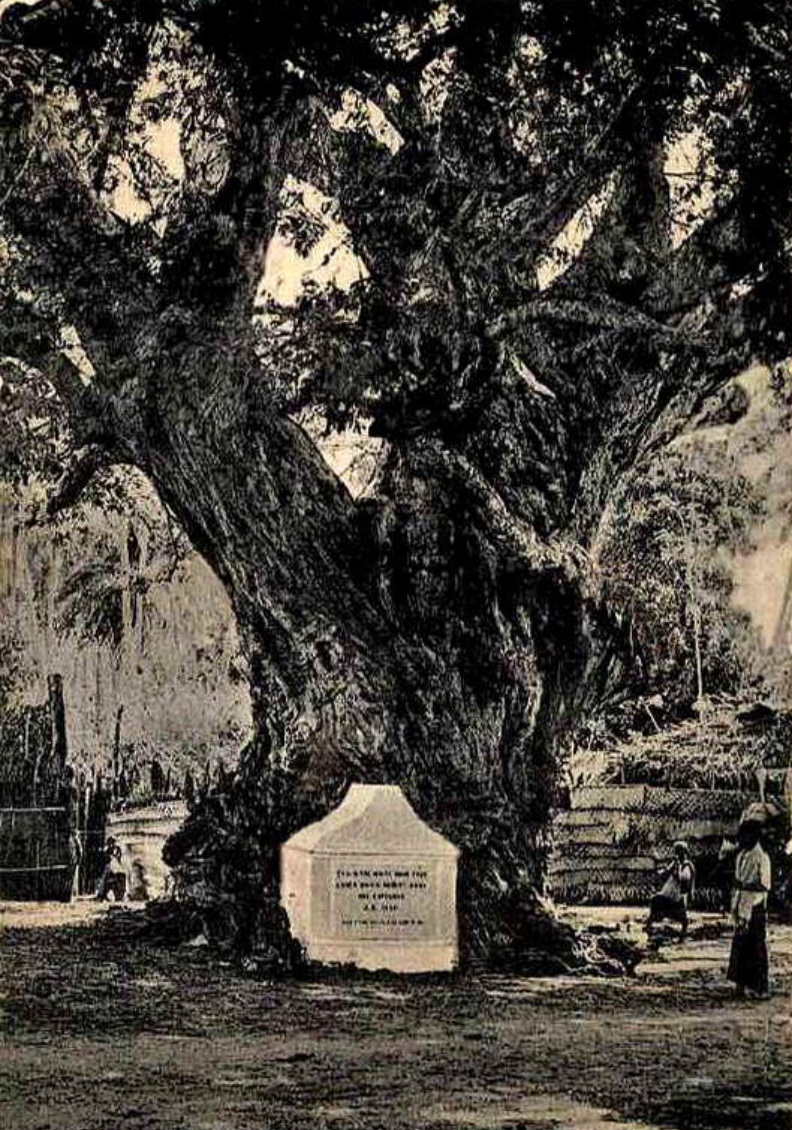

… the Captain mistrusting nothing, came up with his Boat into a small River, and being come ashore, sat down under a Tamarind Tree, waiting for the Dissauva and us. In which time the Native Soldiers privately surrounded him and his Men, having no Arms with them; and so he was seized on and seven men with him, yet without any violence or plundering them of any thing; and they brought them up unto us, carrying the Captain in a Hammock upon their Shoulders.

The following day, the long boat’s crew were seized as they came ashore to obtain timber. That night, the two sets of Englishmen slept apart in Kottiyar, ‘the House wherein they kept the Captain and us … all hanged with white Callico, which is the greatest Honour they can shew to any.’ Although they were well treated, no contact was permitted between the groups. [5]

The stand-off continued for a few days before Robert was permitted take a message from his father to the Anne’s chief mate, John Burford. He was told to depart if the captives were not released within twenty days. Robert then returned, making considerable play in his account of how he remained true to his father’s injunction to do so:

My fathers Charge to me was very urgent for my returne, fearing lest, he sayed, if I should not it might occation the losse of his life, which I would not put to the hazard tho with the lose of my owne liberty; and indeed it would al my life time have bin a burden one my Consscience that I thank God I never repented obeying my father’s Command, tho after my father repented before I came one shore that he had given me so strict a Charge to returne.[6]

Knox in the Kandy Kingdom

In January 1661, Madras reported the capture to London.

To begin with, they declared that no fitter place than Trincomalee could have been chosen to mend the Anne’s defects. As these were being repaired with timber and knees cut in the adjacent woods, Captain Knox and his men had been treated with ‘noe small Courtesy.’ Daily, they were presented with ‘cowes, bufflowes, deere, hoggs, antelopps, fowle, and all sorts of fruite, in recompence of which the countrey people were soe free, that they would receive nothing.’

Yet this was ‘but a meere baite and delusion to entrapp Capt. Knox & his men’:

… for by his indiscretion, sufferring soe many of his men to be on shoare at one tyme, the Chingulaes (the natives of the countrey) under pretence to goe up to the King of Candy to fetch a letter and present for us, surprized Capt. Knox, Mr. John Loveland and 15 more of the ships company; and it is a wonder a greater number were not taken, for sometymes so many of his men were permitted ashoare at once that there were not above three or four aboard to keepe the ship …

Despite the criticism, Fort St. George expressed surprise at the actions of the Kandyans. It had been ‘a usuall thing for ships to goe in there & refresh and trim, both of ours and the Danes.’ During his earlier visit, Charles Wylde – in the company of the Anne’s John Burford – had stayed many days, and his men had travelled more than thirty miles into the country.

To conclude, Madras declared that they were remitting letters of credit to furnish necessities and ransom the captives, ‘if it may be done with money.’ They expressed ‘great hopes that all will very suddenly be redeemed.’[7]

The Dutch, betweentimes, were reporting that the Anne’s crew had come ashore, cleared the jungle and, though suffering from a fever that proved mortal to nine, had prepared the palisade for a fort. They say that they sent a force to protect the bay against invasion, but Knox makes no mention of such activity. Instead, he infers that, as they awaited the order for their release, the crewmen experienced a peculiarly restrained kind of captivity:

Tho our hearts were very heavy, seeing our selves betrayed into so sad a Condition, to be forced to dwell among those who knew not God nor his Laws; yet so great was the mercy of our gracious God, that he gave us favour in the sight of this People. Insomuch that we lived far better than we could have expected, being Prisoners, or rather Captives in the hands of the Heathen; from whom we could have looked for nothing but very severe usage.[8]

After the Anne’s departure, the dissava was summoned to Kandy for consultations. He took his troops with him, leaving the captives where they were. About them, wrote Knox, ‘there was no order at all.’ For sixteen days, they waited. Then they were told they were being taken into the heart of the kingdom. Captives they remained, although, as they threaded their way through the woods, they were treated almost as guests:

As they brought us up they were very tender of us, as not to tyre us with Travelling, bidding us go no faster than we would our selves. This kindness did somewhat comfort us. The way was plain and easie to Travail through great Woods, so that we walked as in an Arbour, but desolate of Inhabitants.

At night, the Englishmen fed among the natives ‘like Soldiers upon free Quarter’:

Yet I think we gave them good content for all the Charge we put them to. Which was to have the satisfaction of seeing us eat, sitting on Mats upon the Ground in their yards to the Publick view of all Beholders. Who greatly admired us, having never seen, nor scarce heard of, Englishmen before. It was also great entertainment to them to observe our manner of eating with Spoons, which some of us had, and that we could not take the Rice up in our hands, and put it to our mouths without spilling, as they do, nor gaped and powred the Water into our Mouths out of Pots according to their Countreys custom.

It was only later that Knox appreciated that the beholders’ admiration was actually disdain, the Kandyans fearing their cups would be defiled by the English ‘beefe eaters’.

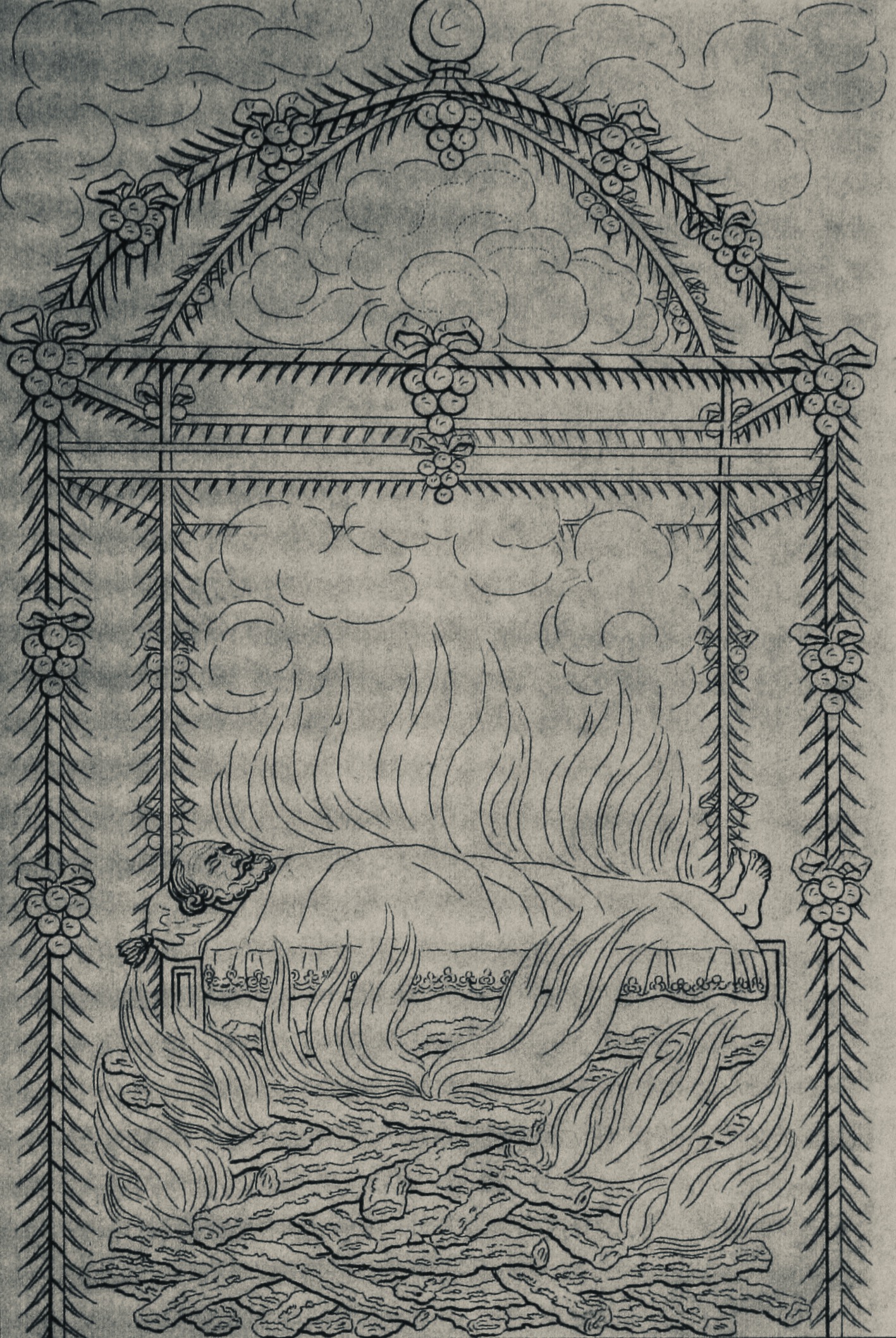

At Hotcourly, the Englishmen were split into groups, to ease the burden on the people. In September, for the same purpose, Knox and his father were set apart and sent to Koswatta (‘Bonder Coos-wat’) to await a summons from the king. Still their accommodation and victuals came gratis, but Koswatta was a sickly place. Captain Knox yielded to depression and disease. He died, on 9 February 1661, after ten months’ captivity, his body ‘consumed to an Anatomy having nothing left but Skin to cover his Bones.’

It deeply grieved him, [Knox wrote] to see me in Captivity in the prime of my years, and so much the more because I had chosen to suffer Captivity with him than disobey his Command. Which now he was heartily sorry for, that he had so commanded me, but bad me not to repent of obeying the command of my Father; seeing for this very thing, he said, God would bless me and bid me be assured of it, which he doubted out of, viz. That God Almighty would deliver me …

Suffering as he then was, from malaria, it was only with difficulty that Knox was able to bury his father’s remains. He was assisted by his servant but, upon being asked, the most the villagers offered was ‘a great Rope they used to tye their Cattle withal, therewith to drag him by the Neck into the Woods.’ (Later, Knox learned that lower-caste villagers were buried without ceremony and that handling the dead was considered unclean. Probably, the corpse of a ‘beefe-eater’ was especially problematic.) There was some comfort that the woods overlooked a cornfield where father and son had walked and discussed their favourite religious tracts. Still, for a time, Knox sank into a depression, believing that even God had abandoned him.[9]

Then there came two signals of hope. First, was the occasion when an old man offered to sell him a book he had obtained when the Portuguese abandoned Colombo. Strangely, it was a copy of the King James Bible. Knox exchanged it for a cap knitted by his servant. It fell open at the sixteenth chapter of The Acts,

… where the Jailor asked S. Paul, ‘What must I do to be saved?’ And he answered saying, ‘Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved and thine house.’

Second, was the reappearance, after a year, of the Anne’s John Gregory. By then, Knox’s clothes had fallen to rags and his money was mostly spent, so he was intrigued to learn that his countrymen were making greater use of being maintained at the king’s command. They were provided with their food uncooked, and in such quantity that they were able ‘to pinch somewhat out of their Bellies, to save to buy Cloths for their Backs.’ Indeed, they had become sufficiently confident that, occasionally, they used violence if they were not supplied as they required.

When Knox asked his minders if his food might not be similarly supplied, he was told it would be beneath his dignity. The king had notice of him ‘by name’, and he might be summoned to the palace at any moment. After some argument, Knox persuaded them that his dignity would be better served if his food were cooked by his servant. He added that his house was too small to accommodate a kitchen. The villagers built him a larger one. Knox finished its walls with lime, little knowing that lime was reserved for royal apartments, and temples. But for this ignorance he was forgiven, although ‘had [it] been a Native that had so done, it is most probable it would have cost him his Head, or at least a great Fine.’

Being settled in my new House, [Knox wrote] I began to keep Hogs and Hens; which by God’s Blessing thrived very well with me, and were a great help unto me. I also had a great benefit by living in this Garden. For all the Coker-nuts that fell down they gave me, which afforded me Oyl to burn in the Lamp, and also to fry my meat in … Now I learned to knit Caps, which Skill I quickly attained unto, and by God’s Blessing upon the same, I obtained great help and relief thereby. In this manner we all lived, seeing but very little sign that we might build upon, to look for Liberty.[10]

There were two principal obstacles to escape. First, white travellers were assumed to be runaways. Watches had been stationed on the roads, who suffered none to pass with whom they were unacquainted. Secondly, and more peculiarly,

The rodes throught the great woods that devide one County from the other are onely unalterable; those woods (onely) they are not permitted to Cutt downe, because they serve for defence in Case of an invasion … But all the rest of the woods being frequently Cut maketh them not onely grow thicke and so unpassable, but also Changeth the way or rode, so that he who was well acquainted with the wayes one yeare the next will be utterly to seeke by meanes of the Alterations as affore said.[11]

Then, in December 1664, Knox and the other captives were summoned to the royal palace at Nilambe. In England, unbeknownst to them, Oliver Cromwell had died, and the monarchy had been restored. The new king required that ‘speedie care’ be taken of the captives, that they might be freed from their bondage. London had instructed Fort St. George to take the necessary steps. At the same time, expressing their appetite for cinnamon ‘of any sort’, they had ordered that a person be sent to Kandy to treat for a factory. If the Dutch proved difficult, they said, King Charles would provide the necessary backing. In the latter part of the year, their message (though not yet an envoy) had reached Raja Sinha.[12]

Fort St. George and the Captives in Ceylon

When he arrived at the palace, alongside the men of the Anne (unseen since their first separation) Knox encountered thirteen other captives of the Persia Merchant. She had been wrecked in the Maldives, in August 1658, eighteen months before his own capture.

After reaching the shore, the Merchant’s fifty survivors had purchased the ‘tottering egshell’ of a native boat. They sailed for Colombo but were caught in a storm and plundered of everything but their clothes at Kalpitiya. (John Merginson hid his money from the natives, but lost it to his crewmates, who lost it to the king.). Immediately, William Vassal, Thomas March and Merginson were seized. Ten others were arrested as they wandered through the woods towards Colombo. (The remainder were wrecked again at Adam’s Bridge, between Ceylon and India. With Dutch help, they escaped to the mainland.)

In Ceylon, the Merchant’s men received preferential treatment in that they were accommodated in Kandy itself. They were afforded ‘a new Mat given them to sleep on’ and their food was brought twice daily from the palace. Their hopes were raised, so that, when a Jesuit priest warned it was not the Kandyan custom to release white men, he was vilified as ‘a Popish Dog and Jesuitical Rogue.’ The Englishmen imagined the priest’s words expressed his wish, before they discovered the truth. Then, they launched a protest:

That the King might be informed how they were abused, each man took the Limb of an Hen in his hand, and marched rank and file in order thro the Streets with it in their hands to the Court, as a sign to the great Men, whereby they might see, how illy they were served … But this proved Sport to the Noblemen who well knew the fare of the Countrey, laughing at their ignorance, to complain where they had so little cause. And indeed afterwards they themselves laughed at this action of theirs, and were half ashamed of it, when they came to a better understanding of the Nature of the Countreys Diet.

Later, the captives applied to Father Vergonse for permission to steal some cows ‘that they might eat their bellies full of beef.’ This he granted, ‘forasmuch as the Chingulayes were their Enemies and had taken their Bodies, it was very lawful for them to satisfie their Bodies with their Goods.’[13]

Knox provides anecdotes about a few of the Merchant’s men. Thus, Hugh Smart, who obtained favour at court until he was caught speaking to the Dutch ambassador, Hendrik Draak. He was sent away ‘a Prisoner in the Mountains without Chains … Where indeed he lived better content than in the Kings Palace.’ (Smart married and had a son before being killed by a falling jackfruit.). Henry Man became head of the palace servants but was then cruelly punished for breaking a porcelain dish and fleeing, for sanctuary, to a temple. His greater crime was his expectation that the priests would secure him against the king’s displeasure. For this, Man’s arms were bound behind him until ‘the Ropes cut throw the Flesh into the Bones.’ After a day, they were untied, but he remained chained by the legs for six months, and his arms never recovered their strength. In time, he returned to kingly favour before, finally, he was torn asunder by elephants for failing to inform His Majesty of a letter he had been given by a Portuguese. It takes little imagination to see why, when Knox was offered a position by Man, he refused it: he would have welcomed deliverance from his solitary condition but he declared that ‘Gods providence overuled it and prevented me from runing into my owne destruction.’[14]

Fort St. George’s first plan for obtaining the captives’ release involved the tactics of blockade. In October 1662, they wrote to London explaining that,

… there can bee noe other course taken then to lye before [Kottiyar] with a couple of vessells, though but of 30 tuns and four gunns a peece; and then the King would understand that the port was blockt up … And in these contingencyes the peoples eyes are only uppon Your Worships, and to have a couple of small ketches or hoyes come out in quarters in a shipps hold, and men shipt out to mann them; and then noe doubt all would bee recovered.

Regarding the practicality of establishing a factory they were less confident. The seizure of the Anne suggested that ‘nothing can bee there undertaken without a fortification and souldyers kept continually in guerrison.’ They appreciated the quality of the harbour, but the Dutch were able to secure only small quantities of cinnamon, in spite of their presence. They feared the trade might not ‘countervaile the charge.’[15]

In January 1663, they committed some further thoughts to paper. They announced that they were applying to Luke Platt, from whom they had received news, to contact Knox and the others. Meantime,

We are intended to have sent a sloope with som fewe men and five or six gunns in her; for which purpose wee have fitted one, and shall endevor by all meanes posible to redeeme them out of so sad and deplorable a condition. But we have advice that, if we should send a vessell there before wee have treated with [the King] at a distance, hee will keepe these men also pris’ners.[16]

The problem was that, in the isolated kingdom of Kandy, severe penalties were inflicted on those who communicated with the outside world. Letters had to be smuggled in and out.

There is no further mention of Platt but, in April, the council informed Surat that they had found a Moor who had agreed to take some messages to the prisoners and the king. They paid him five pagodas a month and expected him to be away for six to eight months. In a covering note to Masulipatam, they explained,

Wee have understood by a particular letter from Mr. Henry Gary at Goa that Ricloffe (Rijckloff van Goens, governor at Colombo), being very prowd with his late successe in taking Cochin, hath publiquely declared that their intentions in taking that place was not only for procuring the pepper and cassia lignum but to make it a magazine and harbour for their shipping (having a designe for taking Zeiloan); for which purpose they have sent 18,000 women for breeders to populate the place. Of which wee shall take all oppertunities to give the King of Candy notice, hoping thereby to make the Dutch more odious in his sight and to ingratiate ourselves; and possibly this may be a meanes for the redemption of our captivated friends, as allso may prove an oppertunity for setling a factory there, according to the Honourable Companies desire.[17]

At the end of 1663, another communication from the captives found its way to Madras. William Vassall sent an account of their condition and ‘what meanes are to bee used for their releasment.’ The council decided to send a vessel to Kottiyar, where they encouraged the captives to gather in readiness, if possible. ‘Soe,’ London was informed, ‘[we] shall leave noe wayes unattempted to bringe them out of their afflicted condition.’[18]

The vessel departed in February, with instructions for the brother of one of the Company’s servants, Perumal Chetty, who had links to the island, to supply the captives with three hundred rials of eight. Thomas Diaz was sent with a letter and gifts – two brass guns, a Persian horse, two hawks, five dogs, some looking glasses and broadcloth – for the king. With these, it was hoped, the captives might obtain liberation and permission to trade. Assuming these were granted, they were offered the opportunity to set up a Company factory, for which the vessel and its cargo might remain at Kottiyar.

The council’s estimation of their servants’ dedication is heart-warming, but the ship never reached Ceylon. The Dutch had learned that Madras was shipping ‘4 brass guns and other rarities’ to Raja Singha through a Portuguese intermediary, and that they sought ‘to get here or there on the island of Seylon a permanent residency.’ As she approached her destination, they turned the ship away.[19]

In May 1664, Madras despatched another letter to the king via Tuticorin. Two more were sent to Vassall, in June and October. On 18 November, they received a response. Immediately, they translated into English the letters sent to the king,

… because [Mr. Vassall] expects to bee sent for before him shortly, and then hee may (haveing the sight of our letters to him) bee the better able to answere him in his demands and treate with him about the setling of a factory.

They explained that, ‘in the highest stile’, they had petitioned Raja Sinha for the captives’ release, promising him that, if it were granted, he would soon see how willing the Company were to support him, ‘if hee would grant us one of his ports there, to trade freely.’

… ‘tis only for want of his lycence that wee come with small boates, whereas, if we had that, wee would come with greate ships that the Dutch could not hinder, and trade there (with his leave) in spight of them.

Further presents would be sent shortly. Accordingly, Madras discouraged attempts at escape until ‘our piscash may worke with the King.’ Finally, Vassall was advised to suggest that, given the raja’s leave, he might,

… write to us to acquaynt the King of England how powerfull the Dutch are growne uppon Zeiloan, and how they encroach uppon the Emperour, and advize him [ie. King Charles II] to send some ships and force thither to the Emperour’s assistance. [20]

On 8 December, the council wrote to London. They recounted how the Dutch, ‘in a most un Christian like Action,’ had intercepted the vessel sent to Kottiyar, and complained that, by characterising the English captives as Dutch, they had caused the king to look upon them as spies. They added that, since Vassall had indicated that Raja Sinha would appreciate a lion, and none were available at Madras, it would be ‘a worke of high Christian Charity’ if one might be procured from Turkey.

As for settling a factory, they explained,

… there is no trusting of the Natives unless wee have a Fort to secure ourselves against their falcity; and besides [Vassall] thinks the Dutch will endeavour to hinder us to have to doe on that Island. Hee heareth, hee saith, the Emperour intends to write to England to know whether our Kings Majestie or your Worships will please to assist him against the Dutch, and with his assistance hee will give you possession of Gaule and Collumba. These things are worthy Your Worships consideration. The Emperour hath a perfect hatred for the Dutch, keeps all the Embassadors they send, not one returnes, and hath cutt of all his greatemen, feareing they should bee bribed to betray his Countrey to them.[21]

All of this correspondence bypassed Knox which, given Henry Man’s fate, he was probably grateful for. He mentions that Vassall received several letters which he kept secret, but that, advised by Father Vergonse, he managed to explain away his failure to Raja Sinha’s satisfaction. This action he calls ‘Mr. Vassals prudence upon the receipt of letters.’ Privately, however, he was more critical. Minutes for the Dutch Council at Colombo, from October 1669, refer to a message addressed to Sir Edward Winter, agent at Madras, by Knox and Loveland, ‘on the leaf of a sugar tree’:

In the year 1664, we received a packet marked 61, and particularly addressed to us, which is all that we have received, although Mr. Vassal has received some, but concealed the fact from us, and money too, which we have not once received, though our neediness is so great … If you can by any means send some assistance, as the bearer Perga [Loveland’s servant from Fort St. George] can direct you, to us poor afflicted captives, we shall not cease to implore for you long life, health, and prosperity, while we remain your Honor’s servants.

The Dutch provided Perga with money and clothes to distribute to the English, but he ran off with them. A letter sent to Madras by Knox and others, in January 1670, confirms as much. In it, they also accused Vassall of pocketing all the money sent for them. They begged the council that they should not be forgotten and that ‘some meanes may be used for our freedome out of this hellish condition.’ They added that, for the sending of aid, ‘the safest way is by Columbo,’ and that it should be directed to the ‘English pilot’ (Merginson) or the ‘English gunner’ (Thomas March) as,

… if it should come to be directed to Wm. Vassall or otherwise called the English Feitor (Factor) the rest of the English will never be ye better for it.[22]

Which returns us to the Nilambe audience. For at it, in a surprise move, Raja Sinha offered the English their liberty. Knox and Knight reported that Hendrik Draak had importuned him for their release. (Knight says specifically that Draak ‘obtained from the king a promise thereof.’ It did him little good. He died in captivity, in 1670.) But clearly, as Knox acknowledges, Madras’s letters had had an effect.[23]

The king promised that any who remained in his service ‘should have very great rewards, as Towns, Monies, Slaves and places of Honour conferred upon them.’ Each was asked to express their preference and all – quite unsurprisingly – chose to return home. By this, says Knox, ‘we purchased the Kings Displeasure.’ The prisoners were told to wait. Days passed, and then, on 21 December, as ‘a fearful Blazing-Star’ filled the night sky, a rebellion erupted, and the palace came under siege.

The rebels’ plan was to replace Raja Sinha with his young son. But the king escaped to the mountains, using his elephant to smash a way through the woods, and when the prince was spirited away by the king’s stepsister to join him, the revolt collapsed. Knox wrote,

We would gladly [have] bin nuters, but [the rebels] would not permitt it; to take armes for them we feared, perceiving noe good order or Command amounge them, the Prince not heading them and the old King a great Politician, his very name dreadfull to the People, and the Countries aboute him had devoted themselves to his service, while the Rebels began to melt with disorder. Thus death stood before us one boath sides, had not God delivered us by the Princes flight, which put the rebles into Confusion.

By refusing to champion the insurgents, and by supporting one of the loyal dissavas at the rebellion’s close, the English avoided retribution, but the negotiations for their release ended. For three months, they subsisted on money given to them by the rebels and on those items which they had secured for themselves in the scramble which followed the prince’s flight. Then they were ‘dispersed about the Towns here one and there another.’[24]

Although he had re-established himself, the rebellion shook Raja Sinha. In 1665, he turned to the Dutch for assistance, an opportunity which the expansionist governor, Rijckloff van Goens, seized upon. In April, companies from Colombo and Galle occupied the strategic strongholds of Ruvanvalla and Bibilegama. The area under Dutch control in the west and south-west doubled in size. Trincomalee was occupied and fortified in the same year and, by 1668, Batticaloa and Kottiyar. By 1670, Holland had control of all of Ceylon’s coast, ports and trade.[25]

With this, English efforts to obtain liberty for Knox and his compatriots fell into abeyance. The outbreak of the Second Anglo-Dutch War ensured that Dutch efforts also ceased. On 9 January 1666, Fort St. George wrote to London:

[Wee] had verily thought wee should have this yeare compassed theire Liberty, and that by meanes of an Englishman, James Sheppard by name, who comeing out of theire service poore and naked (the better to cover his mischeivous designe) wee clothed, putting him into a handsome Equipage; who haveing the Language of that Island and proffering Himselfe soe ready to undertake the procurement of theire Liberty, Wee thought him a fitt instrument to endeavour theire Enlargement, but hee had not bin long gone from us, when wee heard of his going to the Dutch Factory of Tutticorine, delivering our Packquett of Letters which Wee had given him for the King of Candy to the Dutch Chiefe, and then Embarques himselfe for Columba; and since wee have heard no further of him.

They confessed that Raja Sinha, who had learned of their presents, had been surprised that ‘wee should suffer the Dutch to hinder theire comeing to him.’ English esteem, they declared, had suffered considerably because of their ‘exorbitant abuses’.[26]

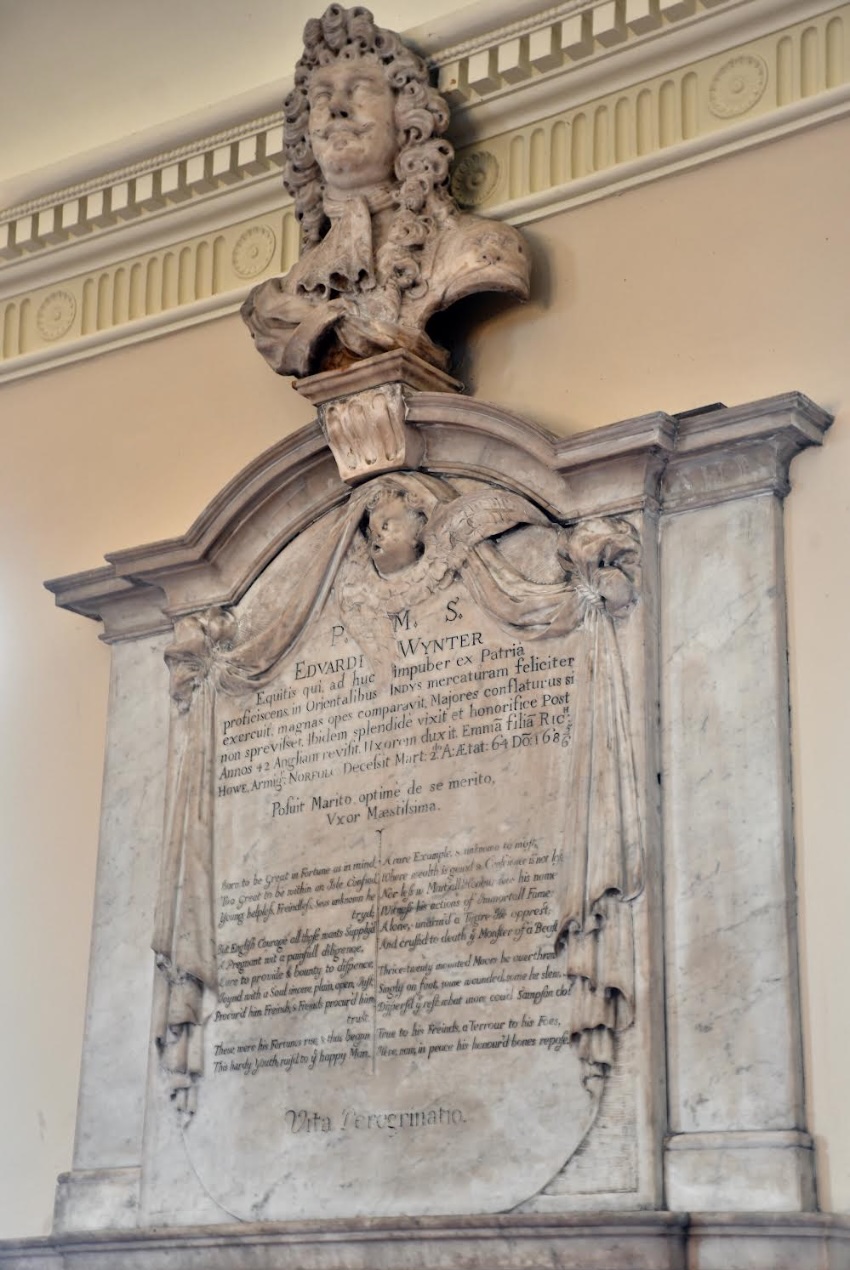

By now, however, Fort St. George was more than a little distracted by the arrest and imprisonment, by Edward Winter, of George Foxcroft, the man sent to replace him as agent. In September 1665, the arch-royalist Winter, who had himself been charged with nepotism, extortion, extravagant spending and sympathy with the Romish religion, seized upon reports of talk at table and charged the puritanically minded Foxcroft with disloyalty to the Crown. In the ensuing confrontation, Judge William Dawes was shot and killed. Foxcroft spent three years behind bars, while the Company attempted to sort out the quarrel.[27]

Finally, in 1668, after the conclusion of a peace with the Dutch, a squadron of ships was sent by London to force Winter’s surrender and reinstate Foxcroft. The Directors urged upon Madras renewed efforts to obtain the Ceylon captives’ release. To sugar the pill, they sent ‘six lustie mastives’, which they expected ‘will bee acceptable to the King.’

By the time Madras next wrote to Vassall, on 4 November 1668, Foxcroft was back in charge. He expressed sympathy with the captives’ condition, ‘haveing our selves … for these 3 yeares past tasted the inconvenience, though not of such a captivity under Infidell, yet of a farr more close and strict imprisonment.’ However, most of the mastiffs had died and no one could be found to take the remainder to Kandy. Foxcroft sought advice on how to proceed, adding that,

… if any occation be to exhaust (enhance) the valorand valew of English mastifes, this story (which is a true one) may be made use of. In anno 1664 a mastife dog sezed upon a gallant horse of a noblemans (the Earle of Bridgwater) and killed him. To prevent the like in future, this dog was appointed to be sent to the Tower to be torne by one of the lyons; which comeing open mouth to him, the dog sezed on the lyons toung and never gave over his hold till the lyon dyed; for which fact he is reserved as a monument ….

Vassall had warned that his messenger could not be trusted with money, so none was sent. Instead, a reward of forty pagodas per head was offered to any who helped the prisoners escape. Foxcroft wrote that, if a safe conduct could be obtained from the king, an effort would be made to send someone to Kandy. However, he doubted whether anyone would be persuaded to take the raja’s assurance on trust. Vassall was asked to understand the difficulty. For the time being, the best the council could do was offer up their prayers ‘until God open some other way to us, which we see not.’[28]

On 5 March 1669, Vassall wrote to complain that he had received no news since December 1664: he feared his correspondence was being intercepted. Confirming the risk facing envoys sent to negotiate the captives’ release, he explained that Hendrik Draak had been refused permission to leave for ‘about 5 yeares, and as farr off as ever.’ (In September 1670, Draak died. Van Goens believed he was poisoned. He mentioned to Foxcroft that his body was sent by the king with ‘seeming griefe’ to Colombo, accompanied by one of his guards, ‘whose fortune, by this delivery, is more than ordinary.’) Perumal Chetty and his brothers, Vassall suspected, had ‘Played the knaves grosely with me having kept all that ever your Worships sent me.’ The brothers were in prison, one ‘for having to doe with a great mans wife,’ the other for involvement in the rebellion. He suggested that to meddle with them would be to court danger to no good effect, but he asked that Perumal be sought out in Porto Novo, and the money he had stolen recovered.

Vassall then reminded Madras of his earlier suggestion of a gift of a lion. Notwithstanding his earlier comments on Draak, he recommended that, before one was delivered, an offer should be made to send an ambassador to treat on trade, if the prisoners were released and if an assurance were given of his safe return. Finally, he touched on the deaths of Henry Man, and of James Gony and Henry Bingham, ‘of a pining disease’, before explaining that John Loveland, Robert Knox and the rest had been scattered across the hinterland. For reasons of security, he claimed, they would be told of his despatch only later.[29]

Knox on Kandy

For himself, Knox writes,

… now we were far better to pass than heretofore, having the Language, and being acquainted with the Manners and Customs of the People, and had the same proportion of Victuals, and the like respect as formerly.

As time passed, the people had become less suspicious that the English were meditating escape. Several had built houses for themselves. Others had married native wives and had children by them. As these tied the captives more to the country, the close watch on their movements had been relaxed.

Henceforward, Knox had three homes. At the first, at Handapandeni – near Kegalle – he went about his business of knitting and trading caps, for two years. This went some way to supplying his immediate wants: his expenditure on clothing was minimal, his shirts having first been sacrificed to make replacement breeches, before these were abandoned in favour of a loincloth (judged easier to ‘gitt one’ with muddy feet). Indeed, there was little need for shirts: Knox says his beard grew to be a span long and his hair covered his ‘carkas’ to his waist.[30]

In 1666, the Dutch built a fort near Handapandeni, and the king ordered that Knox and four others move closer to Kandy, ‘fearing that which we were indeed intended to do, viz. to run away.’ They were relocated to the misty hills at Legundeniya (‘Laggendenny’). Knox says this was ‘one of the most dismal places that I have seen upon that Land,’ a location to which the king oftentimes sent ‘such Malefactors as he was minded suddenly to cut off.’ The day after his arrival, however, his fears were allayed when a comforting proclamation was made, telling the villagers that the Englishmen were highly esteemed and intended for promotion to the king’s service. They were to be entertained accordingly, and if this were beyond the villagers’ capacity, they were to

… sell their Cattel and Goods, and when that was done their Wives and Children, rather than we should want of our due allowance: which he ordered, should be as formerly we used to have: and if we had not Houses thatched, and sufficient for us to dwell in, he said, We should change and take theirs.

The imposition was intended as a punishment. The villagers’ role had been to carry the raja’s palanquin and supply his daily milk. Living close to Nilambe, they had been in the vanguard of the 1664 rebellion.[31]

At Legundeniya, Knox lived three years, ‘by which time,’ he wrote, ‘we were grown quite weary of the place, and the place and People also grown weary of us, who were but troublesome Guests to them.’ Whilst there, however, he bought a parcel of land at Eladetta, where, assisted by Roger Gold, Ralph Knight and Stephen Rutland, he built a house.[32]

They established a kind of bachelors’ commune, ‘to prevent all strife and dissention,’ and grew and traded corn. Before long, however, two of the group, ‘seeing but little hopes of Liberty’ and thinking it ‘too hard a task thus to lead a single life,’ succumbed to marriage. The others thought long and hard about the lawfulness of ‘whether the Chingulays Marriages were any better than living in Whoredome.’ They concluded,

We were but Flesh and Blood, and that it is said, ‘It is better to Marry than to burn,’ and that as far as we could see, we were cut off from all Marriages any where else, even for our Life time, and therefore we must marry with these or with none at all.[33]

Knox and Rutland remained single.

Marriage would have suggested greater commitment to the place, but the villagers were persuaded that Knox’s homestead represented a sufficient tie. The captives were allowed to move about more freely. In the dry season, when the ways were passable, they increased the range of their trading circuit, seeking out routes to the northward, as offering the best means for escape. Several years passed before it was obtained. In the meantime, Knox committed much to memory of the flora and fauna, and of the customs, usages and character of the Kandyan state.

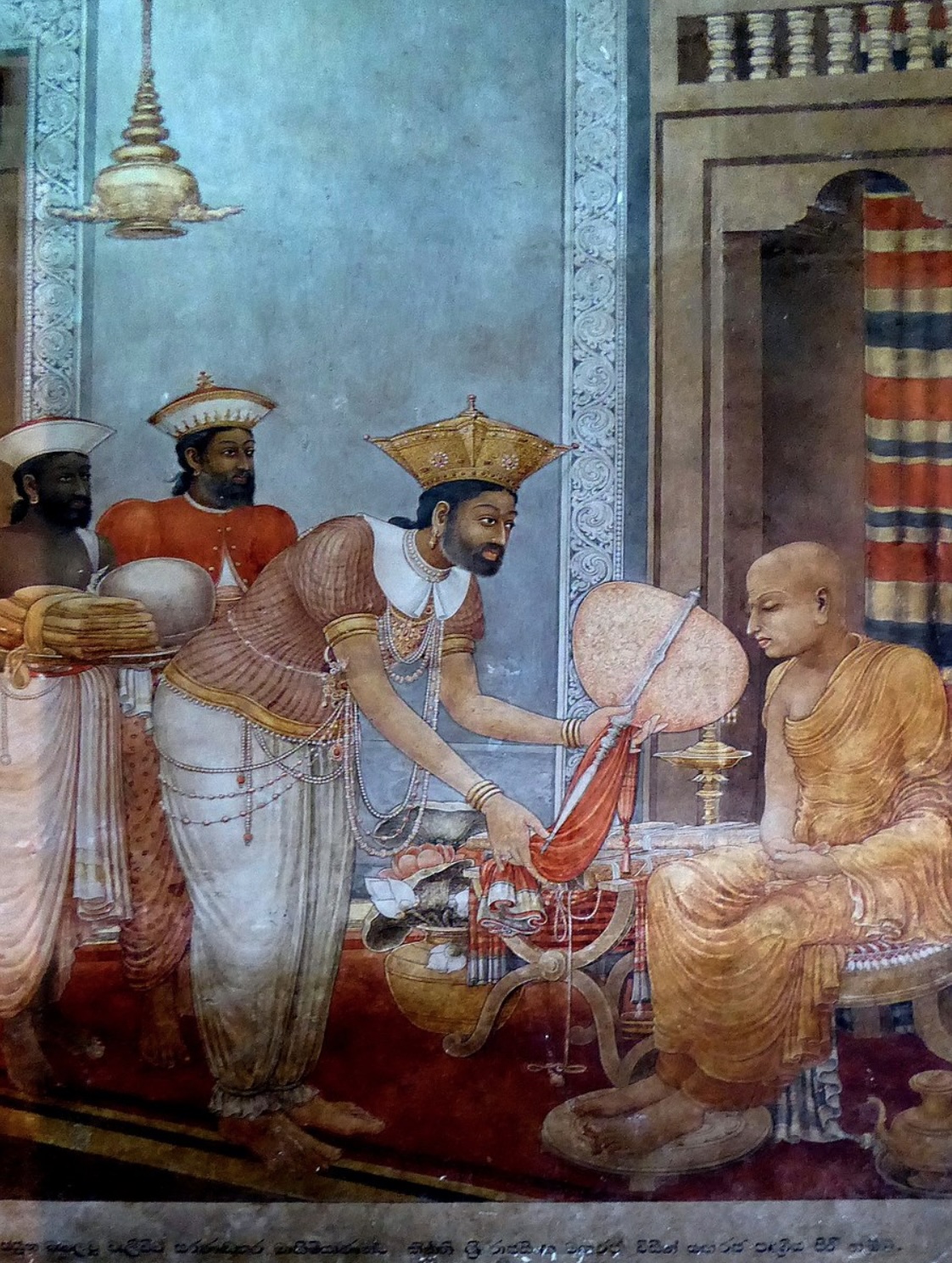

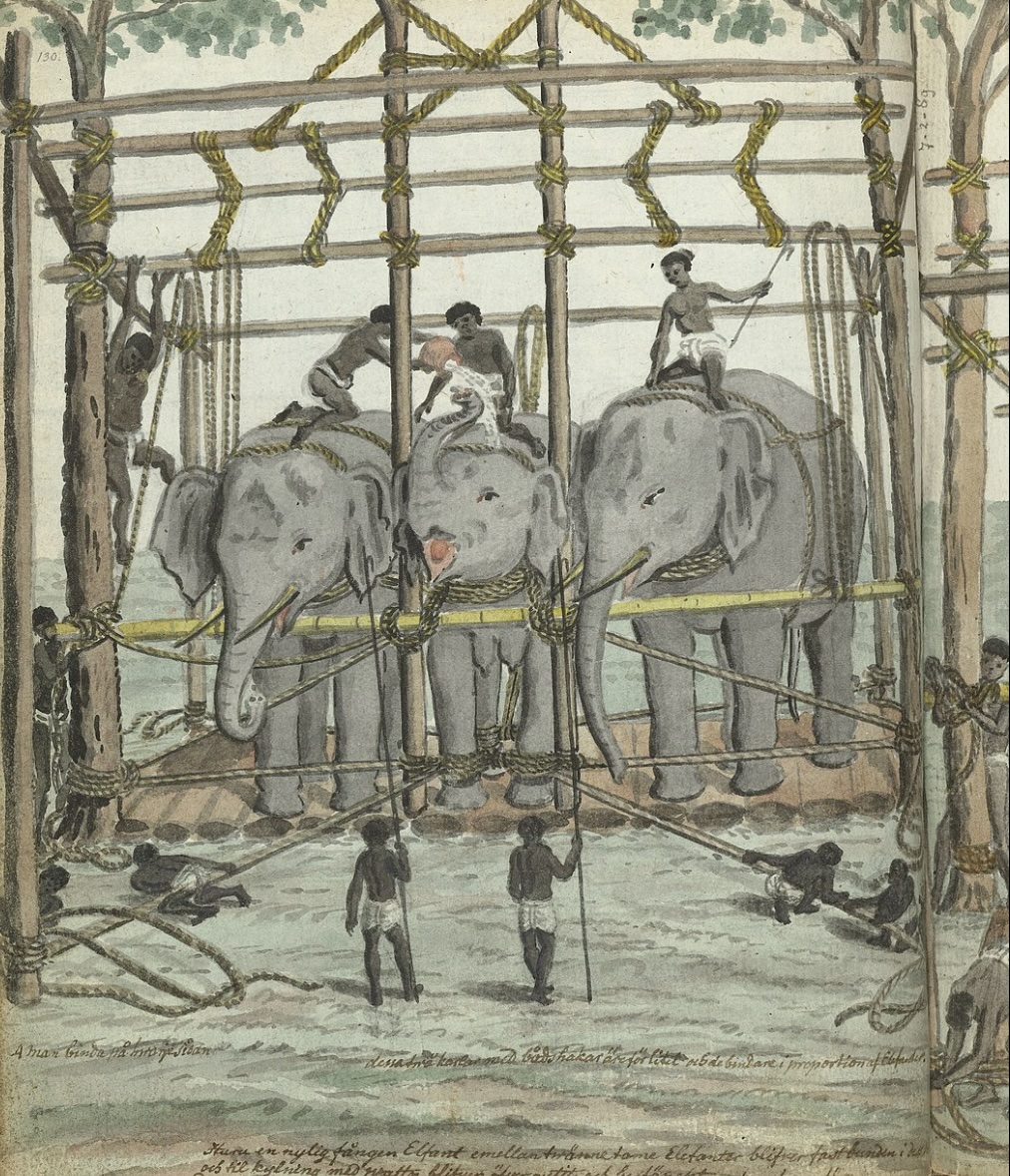

The raja receives a mixed appraisal. He was ‘a very comely man’, fond of swimming, his horses, his elephants and the other animals in his menagerie. He did not persecute Christians:

God’s name be magnified that hath not suffered him to disturb or molest the Christians in the least in their Religion, or ever attempt to force them to comply with the Countrey’s Idolatry.[34]

Yet, Knox wrote, ‘Under the Consideration of his Manners will fall his Temperance, his Ambition and Pride, his Policy and Dissimulation, his cruel and bloody Disposition.’ ‘Temperance’ came in two forms: his diet – ‘his chief fare is Herbs, and ripe pleasant Fruits’ – and his abstemiousness with women. This, he insisted, should apply to his nobles, even to the extent that ‘often he gives Command to expel all the women out of the City, not one to remain’:

But by little and little when they think his wrath is appeas’d, they do creep in again. But no women of any Quality dare presume, and if they would, they cannot, the Watches having charge given them not to let them pass. Some have been taken concealed under mans Apparel, and what became of them all may judg, for they never went home again.

The raja’s pride and ‘affectation of honour’ were ‘unmeasurable’,

Which appears in his Peoples manner of Address to him, which he either Commands or allows of … I have seen the Knees of some that are frequently before him as hard as the soles of thire feet by thire often kneeling, which they shew in testamonie of honour being favorits.

Fear of plots led to heavy security. The king’s commanders were forbidden to confer and, not infrequently, they were executed. In short, service at court was something most definitely to be avoided:

If out of Ambition and Honour, I should have embraced the Kings Service, besides the depriving my self of all hopes of Liberty, in the end I must be put to death, as happens to all that serve him; and to deny his service could be but Death. And it seemed to me to be the better Death of the two. For if I should be put to Death only because I refused his service, I should be pitied as one that dyed innocently; but if I should be executed in his Service, however innocent I was, I should be certainly reckon’d a Rebel and a Traytor, as they all are whom he commands to be cut off.

Knox mentions the case of thirty Europeans who were recruited, in 1675, to assist in an attack against the Dutch at Bibilegama. The fort was subdued without them, but they had been issued with uniforms, and these had to be utilised. The raja retained them as guards and reduced them ‘to great Poverty and Necessity. For since the Kings first gift they have never received any Pay or Allowance.’[35]

One servant of the raja who did better than most was the Englishman Richard Varnham. The commander of numerous soldiers, and all the cannon, he was given a fiefdom comprising several villages. There was an irony in this, however, as,

This man had nothing in him to qualifie him for so high a post in the Kings Court and exceedingly given to drunkennesse, that with the helpe of a Whore he wasted all his whole incomes, which with prudent management would have bin sufficient to have maintained all his English Country men one the land plentifully … His Comly person and presence so far prevailed with the King, that, when he hath bin drunke at his post in the Kings presence, the King hath ordered to lead him home, excuseing him saying he was sicke. Should any of his fellow Courteours have had such a dissease in the Kings presence, doubtlesse he should have paid his head for it.[36]

And yet one receives the impression that Raja Sinha’s tyranny affected the people at large comparatively little. Except when they were required to contribute labour to public works, they were governed with a relatively light touch. Even in the management of the king’s estates, feudalism operated with a curious twist:

… the People enjoy Portions of Land from the King, and instead of Rent, they have their several appointments … so all things are done without Cost, and every man paid for his pains … These Persons are free from payment of Taxes; only sometimes upon extraordinary occasions, they must give an Hen or Mat or such like, to the King’s use: for as much as they use the Wood and Water that is in his Countrey. But if any find the Duty to be heavy, or too much for them, they may leaving their House and Land, be free from the King’s Service, as there is a Multitude do.

‘Here are no Laws,’ Knox tells us, ‘but the will of the King … Nevertheless, they have certain antient usages and Customes that do prevail and are observed as Laws: and Pleading them in their Courts and before their Governors will go a great way.’[37]

In the brief account of Kandy left by Thomas Kirby and William Day, in 1683, the regime appears more explicitly ruthless. They claimed that foreign captives of all nations were ‘badly treated by the great dissavas and others who had supervision of them, who placed them in irons or otherwise cruelly treated them.’ The raja’s rule, they said, ‘continues with unabated rigour and cruelty towards his subjects, many of them being sent for execution on the merest suspicion, without due enquiry.’ If one of the birds in the royal menagerie lost its feathers, it was sufficient cause. Perhaps, however, there was a deterioration in Raja Sinha’s final years. Kirby and Day suggest the severity of his tyranny fluctuated with the pain of his final condition and the advice of his soothsayers, which made him ‘fickle and unstable’.

Certainly, Raja Sinha’s peculiar treatment of ambassadors and other luckless Europeans left the nations with whom he had dealings non-plussed. As at least one historian has observed, if the proverb ‘I gave pepper and got ginger’ were used, in the sense of obtaining a poor bargain, to refer to the policy of using the Dutch to rid Ceylon of the Portuguese, it would not be unjust. Raja Sinha was a wily king. He kept his kingdom intact, but he achieved his object at the cost of isolation and developmental stagnation.[38]

Of the Kandyans’ ordinary behaviour and customs Knox is a valuable source because, as an outsider, he is interested in details too commonplace for others to notice. Alongside his descriptions of their religious practices and toleration, of the Veddas (the ‘Wild Men’ of the woods), of the operation of the caste system and the marriage laws, Knox mentions the Kandyans’ manner of making lime by whirling burning snails’ shells wrapped in withies about their heads, that there was no talking when rice was being served for fear it would not swell, and that,

… [while] heretofore generally they bored holes in their ears, and hung weights in them to make them grow long, like the Malabars, but this King not boring his … that fashion is almost left off.

He even informs us of how they ‘geld their cattel’:

They let them be two or three years old before they go about their work; then casting them and tying their Legs together they bruise their Cods with two sticks tied together at one end, nipping them with the other, and beating them with Mallets all to pieces. Then they rub over their Cods with fresh Butter and Soot, and so turn them loose, but not suffer them to lye down all that day. By this way they are secured from breeding Maggots. And I never knew any die upon this.[39]

Escape

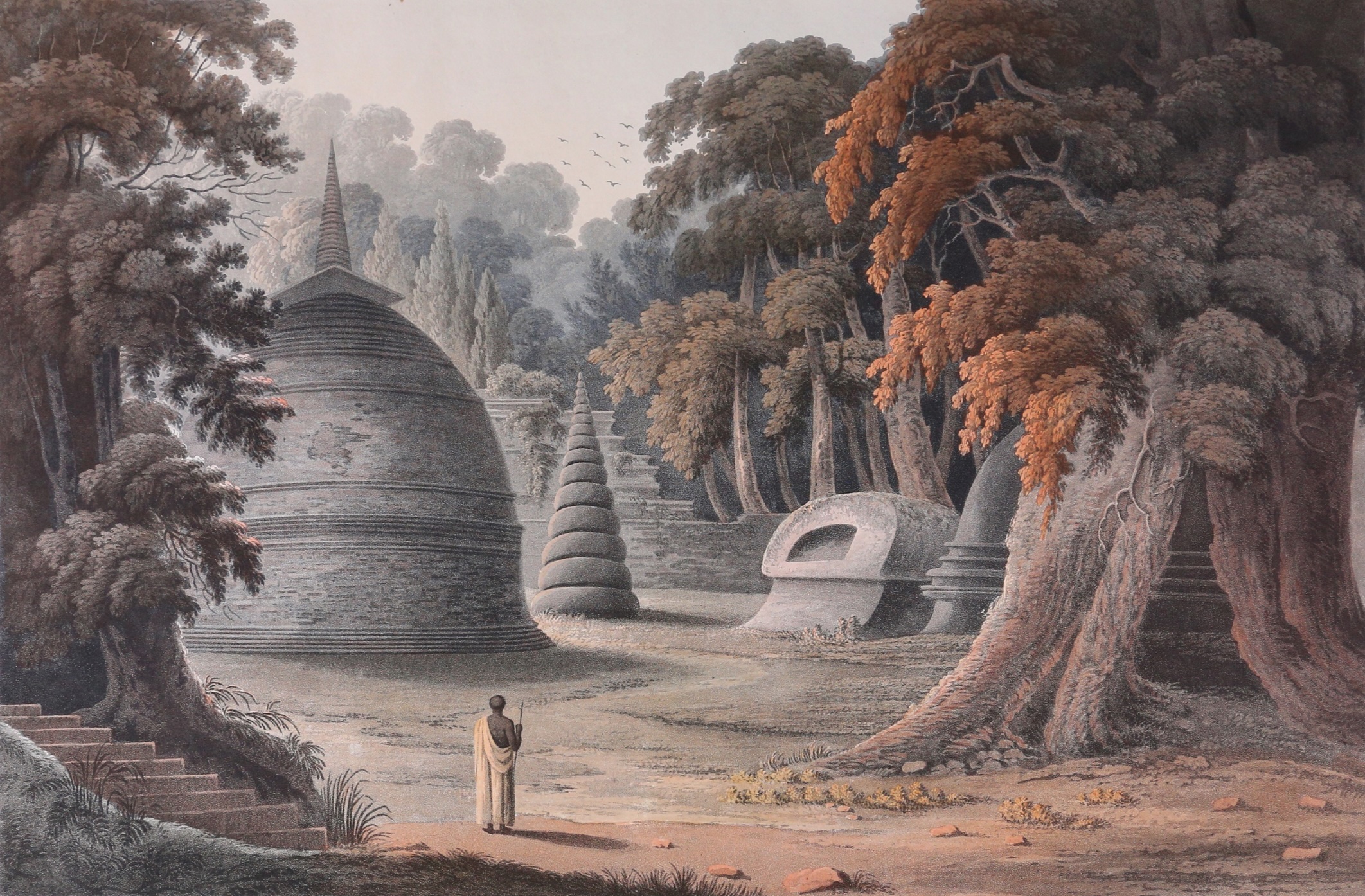

After several false starts, Knox and Rutland finally made their escape, in September 1679. Slowly, they made their way to the northern lowlands, hiding in the jungle, until they reached Kaluvila, where they bluffed their way past the examining official with the pretence of bartering their wares for dried venison, a specialty of the district. Narrowly escaping a party sent by the king to warn of the need to watch for ‘persons of quality’, Knox and Rutland reached Anuradhapura. Again they were examined, but they convinced the governor that, as they had just come from his counterpart at Kaluvila, it could hardly be for white men that the watch order had been issued.

They stayed three days, considering their next move. The Jaffna Road, they decided, was too full of risk, so they backtracked a little and followed a stream which flowed from Anuradhapura to the sea. Creeping at night along forest paths, they escaped the wakeful population in their villages, the elephants, and the wild Veddas, whose presence was betrayed, in encampments made of the boughs of trees, by the bones of cattle and the shells of fruit. Finally, beside a river, they encountered someone who told them they had reached Dutch territory. And so,

… by the great providence of God [I] was sett at Liberty one the eighteenth October 1679, by which it doth appear that I was prisoner one Ceilon nineteene years six months and fourteene dayes, which is fower months and seventeene dayes longer than I had lived in the world before I was taken prisoner thare.

From Manaar, Knox travelled with Laurens Pijl, the Dutch commander at Jaffna, to Colombo. He then embarked for Bantam and England, reaching London in September 1680.

Knox and Rutland were not the last to escape. Charles Beard and Ralph Knight, both of the Anne, reached Colombo, in February 1681, William Day and Thomas Kirby, of the Persia Merchant, in April 1683. The minutes of the Dutch Council at Colombo, for 12 June 1703, refer to the arrival there of Robert Mundy, who deserted the Rochester at Trincomalee, in 1688, and of William Hubbard (‘Herbert’) and his son Peter, born of a native mother. (Hubbard was the last of the Anne’s men to escape. He died at the Cape on his homeward voyage.)

Most of the captives remained where they were until death. For some, life as an Englishman in Kandy may not have compared ill with that of a seventeenth century mariner. It was not true for all. In a letter of 7 March 1691, William Vassall mentioned two other survivors of the Persia Merchant, three of the Anne, three of the Herbert, captured in about 1683, and two of the Rochester. They were, he said, ‘in a very missarable condition’ and begged for relief and ‘news of late Years … being in very great necessitye and sadness.’ In 1696, of the thirty-four captives he knew, six had escaped, twenty-one had died and only seven were living.[40]

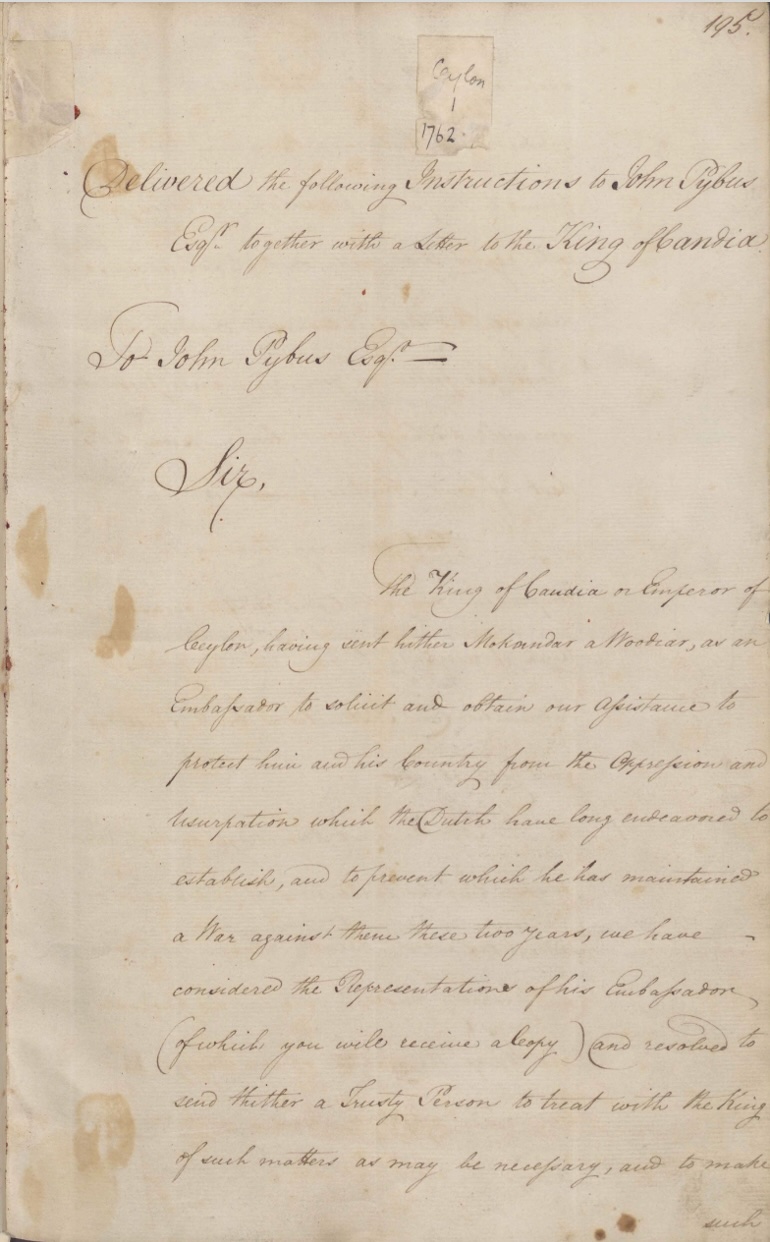

The Embassy of John Pybus (1762)

With Knox’s exit, we lose the winning window onto Kandy society that his Relation supplies. It is not until 1762 that we get the next detailed account in English.

Day and Kirby reported, in the account of their escape, that Raja Sinha had not appeared in public for nearly a year, and that he was greatly weakened with age. Tensions with the Dutch persisted, but van Goens’ forward policy had been costly and, in terms of cinnamon collection, ineffective, as Kandy controlled the supply of labour. In 1681, Batavia urged its administration to agree a peace recognising the lands seized since 1665. That this was not done reflected the raja’s unwillingness to negotiate when the territories were in Dutch hands and, from the Dutch perspective, the king’s increasing frailty. As his policy became less forceful, they saw fit to retain their territories as a bargaining chip to use in negotiations with his successor.[41]

Raja Sinha died, aged seventy-nine, in 1687, after a reign of fifty-two years. However, Kirby and Day’s fear that a succession struggle would plunge Kandy into civil strife was unfounded. The state remained quite stable, even with the accession, in 1739, of the Nayakkar dynasty, which had its origins in southern India. Raja Sinha’s successors were less assiduous than he in fomenting resistance and, since the Dutch were unlikely to obtain a decisive advantage, they agreed to co-exist. Then, in the 1740s, as the influence of the Indian faction at Court (against which the Dutch had been working) increased, the Dutch raised impositions on agricultural output. Opportunities for Kandyan meddling on the coastal plain multiplied and, in the early 1760s, tensions broke into open warfare.[42]

In 1762, Kirti Sri Raja Sinha applied to Madras for assistance. His approach was well-timed, as the Seven Years’ War had alerted Britain to the vulnerability of the Coromandel Coast to acts of French aggression. Ceylon had risen in strategic significance. Fear of upsetting the neutral Dutch meant Britain was not yet ready to take control of Trincomalee, but she was interested to explore alternatives. She was becoming a great power in India even as economic fragility meant that the Dutch were losing their grip on their Indies possessions and trade. It made sense for the British to assess the situation on the island.

The exploratory nature of John Pybus’s mission goes some way to explaining its failure. His instructions indicated that he was being sent in response to Kandy’s request, and ‘to make such observations on the Country, Power and nature of the government, as may tend to promote the future advantage of the Company with regard to Trade.’ Pybus was told to keep his commission ‘a profound secret.’ The Company wished to be sure of its ground before entering into any engagements with the king, or quarrels with the Dutch. He was therefore ‘by all means to avoid any Promises or Conclusive Proposals.’ Nonetheless, he was to ‘proceed in appearance as if we meant heartily to enter into the King’s views, and are to reduce into Articles what His Majesty expects from us.’ In particular, if the king offered to surrender any port, or permanently to grant any place useful in the trade of cinnamon, Pybus was to inform Admiral Cornish, the commander of the squadron taking him to Trincomalee, ‘and request that he will lend assistance to take Possession of and maintain the same.’[43]

Afterwards, Pybus wrote,

I had very little reason, I must confess, to be satisfied with this visit, which proved only a visit of fatigue; nor could I, from the distance I was situated at from Candia, the difficulty, uncertainty, and ceremony which attended getting access to His Majesty, added to the very tedious and tiresome manner in which I found it was customary to converse with him when admitted, entertain much hope of concluding any business in time to return to the Squadron.[44]

The core problem was that, whilst the king was willing to grant the Company a harbour, a settlement, and an exclusive share of the cinnamon trade, in return he expected armed assistance against the Dutch. Although Pybus included in his draft treaty language referring to the provision of troops and military stores (at Kandy’s expense), at the end of the day, this was something to which Britain was unwilling to accede. When Pybus’s draft was presented to Madras it was not ratified.[45]

Considering Knox’s descriptions of Kandy’s wooded ways, and of his escape to the lowlands, it should not surprise that Pybus’s journey in the reverse direction was arduous. He left Trincomalee, on 5 May. That evening, frustrated by the performance of the bearers of his palanquin, he wrote,

… having been obliged to walk the greatest part of this day’s stage, and finding the woods very troublesome, I do not much like the first appearance of my expedition, which, although I am told will not be above five or six days at farthest, I am afraid, by what I can judge from the outset of it, will be very tedious.

‘Tedious’ is a word that came easily to John Pybus.

On 15 May, he reached the guarded pass of Nalande, marked by an old iron three-pounder:

About 8, the General did me the honour of a visit; and upon my desiring him to sit down, he begged to be excused, having something to say to me in the name of the King; and I find no one is allowed to transact any affairs, or discourse upon any business in his name, sitting, without his particular leave … Some compliments passed between us on this occasion; which done, he was prevailed on to sit down, and after a short conversation, he got up again and said he had something more to mention, which he hoped I would not take amiss; and upon coming to an explanation, I found it was to acquaint me that as an arched bamboo to a pallankeen was not allowed to any but the King, he was under the necessity of desiring me to take off mine, and offering to furnish me with a straight one, which he had brought with him, for tomorrow’s journey.

Pybus had received his introduction to Kandy’s onerous system of protocols.

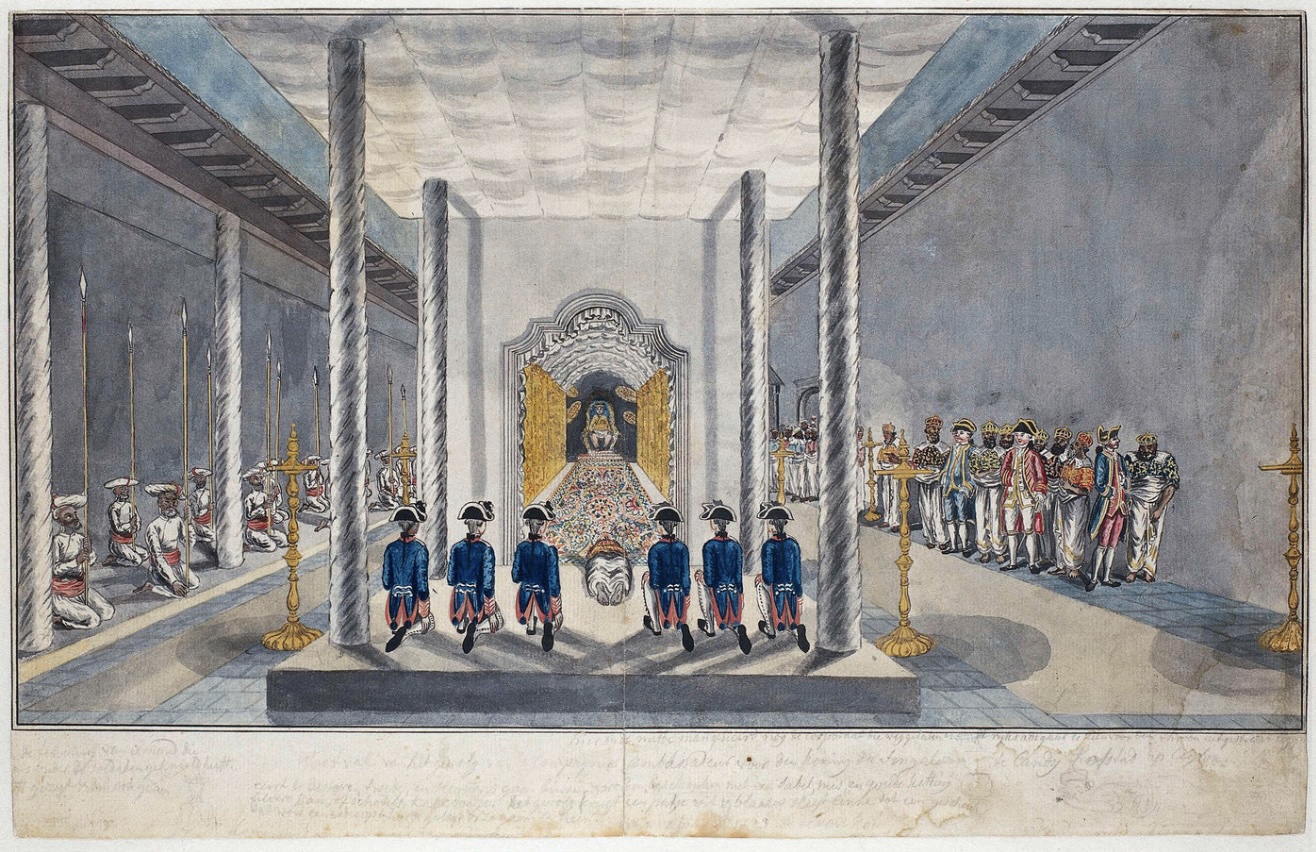

On 18 May, having ascended ‘a most stupendous hill’ partly by crawling, Pybus was told to wait in a specially constructed reception hall, to obtain the king’s permission to proceed. Over several days, he received various officials, who asked him familiar questions about his health and the comfort of his journey. On 23 May, he was informed he would be received by the king the following evening. The next day, the heavens opened. At six o’clock, a group of officers approached a nearby river. Pybus was asked to meet them in the rain, as protocol required. Afterwards, they accompanied him back to his accommodation.

I then desired they would acquaint me whether any, and what ceremony was to be observed in carrying [my] letter; which readily consenting to, they conducted me into the room where the letter was lodged, and producing a silver salver, which they had brought with them for the purpose, covered with two or three pieces of fine muslin, they desired I would deliver them the letter; which having done, they laid it upon the muslin, covering it again with as many folds more, and over all a square piece of silver tissue, with large silver tassels at each corner, and then delivered the dish into my hands, which, by their directions, I carried a few steps from the room, white cloth being spread on the ground as far as I was to walk with it, holding it a little above my head, where a person received it from me and placed it upon his head; two people holding a canopy over it made of China silks, such as are used by the Moors. While this was doing, two drums and some country musick, which had been brought for that purpose, began to beat, and eleven guns were fired from the other side of the river; and in this manner, they told me, it was to be carried all the way to Candia, where, after entering the King’s house, I was to receive it and present it to His Majesty.

At seven o’clock in the evening, they set out for the palace. In a deluge, the procession, accompanied by drums, lights and music, returned to the river. The ferry consisted of a canoe. Since the assembly was large and the current strong, the crossing was ‘tedious’. At a quarter past eight, the party reached the other side. Pybus assumed that, from there, a palanquin would convey him to the palace. He was mistaken. Kandyan officials were required to walk, and they asked him to do likewise. At ten o’clock, they stopped at a little shed, where the ambassador was permitted to change his shoes and stockings. Since he was ‘pretty well besmeared,’ he was glad to do so, but there was still some distance to cover, and by the time he reached his destination, shortly after half past eleven, he was ‘as dirty as ever.’

At this late juncture, Pybus was informed that he was expected to kneel when he presented his letter. Not having been warned of this earlier, he decided he had been treated ‘very disingenuously.’ He requested a special dispensation, on the grounds that he had come not ‘on the footing the Dutch embassadors do … [but] at the King’s particular request.’ To no avail. He ‘could do no otherwise than submit.’

A little closer to the palace doors, he was asked to remove his shoes which, since he was standing in mud, he refused to do until he was within reach of dry ground. This was accepted. Then he was ushered into the presence.

At length, the white curtain at the door was drawn up, behind which, a few yards advanced in the hall, was a red one; this being drawn, a little further was a white one; and so on, for six different curtains, which discovered the end of the hall, where was a door with another white curtain before it. A few minutes afterwards, this was drawn, and discovered to us the King seated on a throne, which was a large chair, handsomely carved and gilt, raised about three feet from the floor.

As Pybus was still standing with the silver dish on his head, he was hauled into a kneeling position by the skirts of his coat. The Kandyan officials prostrated themselves at full length six times. They took a few paces forward and repeated the ceremony three more times. Then Pybus presented his letter.

The hall was fifty feet long, thirty feet broad, and badly illuminated. The raja was wearing a golden robe over a close-fitting vest, with a richly embroidered belt. On his head, he wore an Armenian-style cap, in scarlet and gold, which was topped with a small crown set with precious stones. There were several rings on his fingers, a dagger with a golden hilt in his left hand and, to his right, a broad sword resting against his throne. On his feet the raja wore crimson sandals, with soles that seemed to be rimmed in ‘a plate of gold.’ Aside from a Persian carpet, the walls, ceiling and floor were covered in white cloth, and the throne was over-suspended with a canopy of white silk.

On each side of the hall sat three ‘Golden Arm Bearers’. They wore around their heads a cloth ‘like the dress of an Armenian woman.’ Each used this to cover their mouth, when they approached the raja, ‘that they might not defile him with their breath.’

At the foot of the throne of state knelt one of the King’s Prime Ministers or Secretaries of State, to whom he communicated what he had to say to me; who, after prostrating himself on the ground when the King had done speaking, he related to one of the Generals who sat at the same end of the hall with me; who, after having prostrated himself in the manner I have before observed, explained it to a Malabar Doctor, who told it in Malabar to my Debash, and he to me. And this ceremony was repeated on asking every question, which rendered it tiresome and troublesome.

By these means, the raja expressed his gratification that the English had sent an ambassador in response simply to the verbal request of one of his messengers. He signified his pleasure that they wished to be ‘his steady and sincere friends.’ Thereupon, Pybus withdrew.

Outside, he complained that he had been inadequately prepared for the ceremonies expected of him. Again, he protested that he should not have had to fulfil every form of obeisance required of the Dutch. However, since he was given a house for his stay, and permission to travel to it in a palanquin, he was assured he had been accorded special treatment.

The subsequent negotiations did not prosper. Pybus made his suggestions, but he could promise nothing, and the Kandyans were disappointed that he demanded specifics, whilst having to defer to Madras for anything other than professions of friendship. On 23 June, there was a second, farewell audience with the raja and, on the following day, Pybus departed.

On 2 July, the general who accompanied Pybus to Kottiyar was received by Admiral Cornish. After an exchange of gifts, Cornish expressed disappointment that his ships had not been given provisions: the natives had been willing to supply them, ‘had they received the King’s leave.’ Pybus says the general ‘seemed somewhat perplexed how to answer this complaint.’ He promised the shortfall would be made up in three to four days, but Cornish was under pressure to return to Madras. He gave the general a tour of the ship and departed with his squadron.

Cornish’s criticisms were as nothing compared with those of Kirti Sri Raja Sinha. The Dutch Council in Colombo reported him as exclaiming that, if Pybus’s proposals reflected Britain’s demands before they had an inch of territory, they would raise terrors once firmly planted. Certainly, the mission hardened Dutch attitudes. They launched an expedition into the hills in that year (which was repulsed) and again in 1765 (which was more successful). The terms of a treaty signed in 1766 favoured Holland. The Kandyans made the connection between Pybus’s embassy and Dutch hostility, and it did not dispose them positively towards Britain.[46]

The Embassy of Hugh Boyd (1782)

Having, in this way, successfully agitated relations, the British now withdrew for twenty years. The business of settling Bengal, and struggles with the Marathas and Mysore, assumed greater priority. In 1780, however, France and Spain reopened hostilities.[47]

The humiliation suffered in America caused the British to focus their attention on the East, the more so as the Dutch had joined the side of France. Plans were developed, in early 1781, for the capture, by Commodore Johnstone, of the Cape of Good Hope. These were forestalled by British indecision but, in November, Negapatam, the Dutch settlement south of Madras, was captured by Sir Hector Munro, and the naval force accompanying his expedition, under Sir Edward Hughes, was sent against Trincomalee. With him sailed Hugh Boyd, with instructions to offer the Kandyans the defensive and offensive alliance against the Dutch which the raja had proposed to Madras, in 1762.[48]

In the interest of speed, Boyd sent a letter to Kandy whilst Fort Ostenburgh was still being invested. Quickly, he discovered that his messenger had been stopped on his way. Orders were issued from the capital that,

… the letter should not be received on the pretext among others that were alleged of the improper Conduct of the English in having attacked Trincomalee and dispossessed the servants of the King (so they affected to call the Dutch) without his permission.

Boyd wrote that,

… it was evident that the politicks of Kandy were now averse to us. The old King [Kirti Sri Raja Sinha] had died a few weeks before any Letter went up, and the Dutch had negotiated at Court too successfully to the misrepresentation of our designs. From the rejection of my Letter it might be inferred that my Embassy was virtually forbidden and that they who had refused to read the writing would not consent to receive the writer.

When Fort Ostenburgh fell, however, Admiral Hughes resolved that, ‘notwithstanding the present forbidding symptoms,’ Boyd should undeceive the king as to where his interests lay. He departed on 5 February 1782, in a party of 173, including sixty-three sepoys commanded by Ensign Cherech. He took three palanquins and two doolies (uncovered litters), although he was disappointed by the use he obtained from them. Rain made the journey as difficult as Pybus had experienced it. The villages through which they passed were poor and frequently deserted, the villagers having decamped on the approach of the British. At one stop, on the banks of Tertolay Lake, Boyd wrote,

The delay of my two messengers, who did not return for an hour and a half surprized me; but I was still more so when they did return with two men the only persons visible in the place. This desertation seemingly at our approach, is not encouraging. Our two visitors, however, pretend to account for it by telling us the inhabitants are gone to their paddy-fields. In point of accommodation, our reception is equally inhospitable. They bring us only one fowl, plantains not ripe and a dozen rotten eggs.

The Kandyans promised that provisions and accommodation were being prepared, but they remained exceedingly scanty. Boyd grew concerned. Fortunately, he gave the messengers the benefit of the doubt, and forbade his force from entering the villages without permission, or from availing themselves of their food stocks, except as a last resort.[49]

At the village of Weshtigall, Boyd received a deputation of officials travelling in advance of a general from Kandy. Their deliberations took place at night. Progress was made although, following Pybus’s lead, Boyd called them ‘tedious’. Afterwards, he and Cherech adjourned ‘to more comfortable business,’

… the discussion of our fowl curry which we can hardly make hot enough to encounter the night cold and extreme dampness of the Dews. It penetrates the tripple covering of my Tent, and not being used to sleep in a cold bath and more than half invalid as I have already been for some time, I feel its effect very unpleasantly. But we have gained our main point – expedition, and shall get on tomorrow.

In fact, Boyd was asked to stay his departure, to give the Kandyans time to drape the house being prepared for him in white cloth. He was required to descend from his palanquin and walk the last bit of his journey, out of respect for the members of court there assembled. Such were Boyd’s first encounters with Kandyan protocol. Another followed when it transpired that the supply of food, though plentiful, consisted only of coconuts: rice was prepared only ‘by immediate orders from the general,’ who had gone elsewhere.

Protocol also dominated Boyd’s discussions. Kandy’s officials suggested that the most appropriate route to the capital was via Colombo (then, of course, controlled by the Dutch), that Boyd needed not so many sepoys in his escort (the king’s might serve), that he should meet the king’s representatives, not at his accommodation, but at a specially prepared ‘pandaul’. Boyd, conscious of the inclement weather, and remembering Pybus’s meetings at his house near Kandy, held firm for three days. Finally, a spokesman resolved the dispute ‘by a resource perfectly satisfactory to me, as to punctilio, though, in fact, the invention of the moment’:

He said … that the place prepared for me not being large enough, the Pandaul was made ready – which was to be considered also as my house. This solved all points.

In most respects, Boyd’s audience with King Rajadhi Rajasinha followed the pattern of 1762:

The removal of the curtain was the signal for our obeisances. Mine, by stipulation, was to be only kneeling, – still with the salver over my head, which became most intolerably fatiguing. My companions immediately began the performance of theirs, which were in the most perfect degree of eastern humiliation. They almost literally licked the dust; prostrating themselves with their faces close to the stone floor, and throwing out their legs and arms, as in the attitude of swimming; then rising to their knees by a sudden spring from the breast, like what is called the salmon-leap by tumblers, they repeated, in a very loud voice, a certain form of words, of the most extravagant meaning that can be conceived, ‘That the head of the king of kings might reach beyond the sun! that he might live a hundred thousand years!’ &c. He answered, very gravely, that we might advance … but not till the aforesaid concert had been repeated half a dozen times.

As with Pybus, the audience consisted, almost exclusively, of an exchange of pleasantries. Boyd’s plea that they move expeditiously to urgent matters at hand,

… lost something in the Cingalese channels it passed through. For his highness, without taking the least notice of it, proceeded to ask me, whether I wished to retire, or had anything farther to mention to him?

Subsequent negotiations were conducted with the generals. Boyd explained that Britain was proposing an alliance and military support against the Dutch, in exchange for provisions for the establishment at Trincomalee. The provisions were granted. The Kandyans then asked some questions about America:

I gave them all the particulars I thought necessary towards making the most favourable impression; and was glad that everything was taken down in writing, that the king might have the more certain opportunity of seeing and considering it distinctly.

Their curiosity being also satisfied as to the power of England, and the justice also of her war with France … they asked many questions about the French power and government. They knew, also, of our war with Spain; and naturally enough insinuated, that it appeared we were rather too fond of war, having so many hostilities on our hands at once.

After this exchange (which finished at four in the morning), Boyd heard nothing for four days. As he attempted to construe what the silence meant, his interpreter suggested that, although the policy of Kandy was ‘still rather unfavourable’ towards Holland, the new raja had been influenced by a powerful clique at court and by the intrigues of the Dutch. Probably, they impressed upon the king the recent successes of Hyder Ali and the French against British India.

A second audience was held, on 14 March. Through prodigious crowds, Boyd processed through mud and rain for a mile to the palace. After the usual ceremonies, the raja declared that the letter sent by the governor of Madras had given him the greatest satisfaction. He agreed entirely with the sentiments contained within it. Rather than go into details, however, he indicated that presents and a letter would be sent to the village of Allwalay, for Boyd to collect on his return. This was not an encouraging sign. Worse followed. Boyd was escorted out of the audience chamber to a gallery beside the palace. There, the chief minister began ‘a long harangue’:

He detailed the particulars of Mr. Pybus’s negociation with them above twenty years ago, and complained of its having had no consequence in their favour; that the government of Madras had at that time deputed that gentleman with offers of friendship, which had been answered by them in a friendly manner; – but that, on his return to Madras, the business, instead of being proceeded on effectually as they expected, seemed to have been entirely dropped, and from that time to this they had never heard a syllable on the subject.

Britain’s treatment had been especially galling as the Kandyans had been on the eve of a rupture with the Dutch. When the rupture broke, they had been left to their own devices:

… now, when a rupture had happened between the Dutch and [the British], the communication was renewed! … These circumstances could not but induce them to think, that our attention to their interest was governed only by adherence to our own.

To this conundrum, the Kandyans had a neat solution:

… to make the alliance sufficiently firm, and sufficiently respectable for [the raja] to accede to, it would be necessary to procure to it the sanction of the king of England, signified under his own hand.

Boyd objected that he was in a position of greater authority than Pybus had been. That, just as he had no need to defer to Madras, Madras had power to commit to the treaty without reference to King George. His arguments served no purpose. The Kandyans were adamant on the point. The negotiations, conducted throughout in the standing position, ended shortly before five o’clock.

Boyd returned to Trincomalee. The day after he left it for Madras, his boat was captured by La Fine, a ship of Admiral de Suffren’s squadron. La Fine was subsequently worsted in an engagement with HMS Isis, but Boyd, ‘being rather indisposed,’ missed his chance to escape with the other English prisoners. For some months, he was detained on the Isle de Bourbon (Réunion), before he was granted his parole. Trincomalee was recaptured by de Suffren, in August, and it remained in French hands until it was returned to the Dutch, in 1783.[50]

For all of that, the entry of the Dutch into the war had been an important milestone in the development of Britain’s eastern strategy. Her chief rival was France but, by joining their side, the Dutch created a threat to British interests. Britain’s purpose, in 1782, was to keep the French out, but her actions alienated the Dutch and frustrated subsequent efforts at co-operation. This impelled Britain to seize Holland’s possessions again during the French Revolutionary Wars. At their end, most were returned but, this time, the Cape and Ceylon were retained as essential to British concerns.[51]

Robert Knox after Ceylon

But, in an account which began with Robert Knox’s arrival at Kottiyar, in 1660, that is to look far into the future. To finish, we return to the surprising turn which Knox’s career took after his return to England, in 1680.

He arrived ‘destitute both of mony & friends,’ but attached himself to his brother, an artist, and his sister and her husband, Edward Lascalles. For a period, he lived in their home and, together, they worked for his entry into the Company:

At my appearing before them, they all bid me welcome to England, & told me they would not detaine me with discours of inquires to keep me from my Relations, but defered that to heereafter, & the next time I appeared before them they ordered twenty pounds to be paid to me & ten pounds to Stephen Rutland which we received accordingly; but Sir Jeremy Sambrooke called me a little one side & put two Gunieas into my hand, who then I knew not, but afterward I went to his owne house to thanke him againe for that Great faviour.

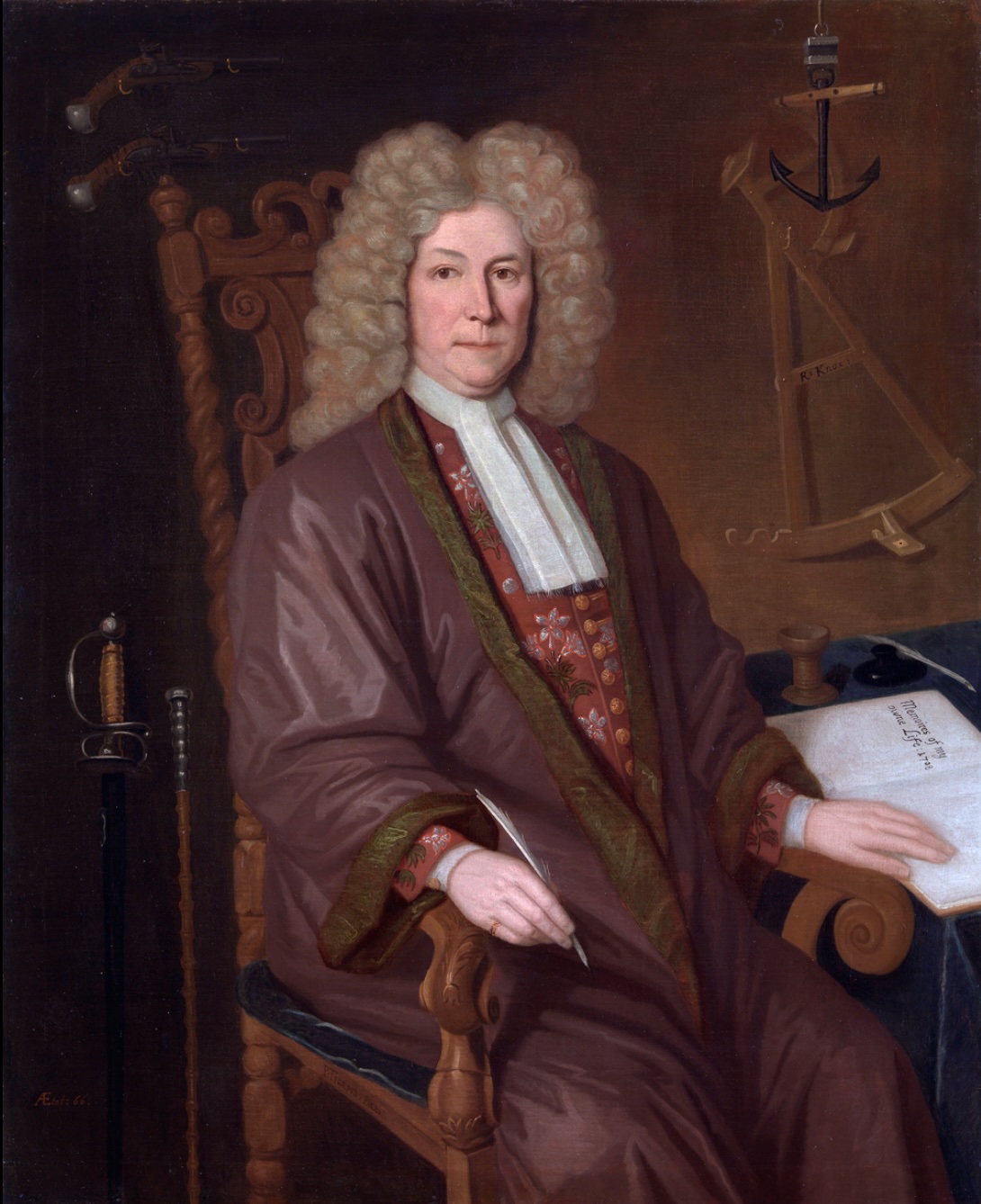

After an introduction from an acquaintance of his father’s, Knox next enrolled in a navigational school in Rochester. Through his cousin, John Strype, he obtained an introduction to Sir Josiah Child, the governor of the Company. Child provided him with the Tonqueen Merchant to command, and recommended that the Company sponsor the publication of his Relation.[52]

By Knox’s own admission, his papers ‘ware promiscuous & out of forme’, but they were brought into shape by Strype, with the assistance of Robert Hooke, the Curator of Experiments at the Royal Society. Hooke contributed a preface commending,

… this Generous Example of Captain Knox, who though he could bring away nothing almost upon his Back or in his Purse, did yet Transport the whole Kingdom of Cande Uda in his Head, and by Writing and Publishing this his Knowledge, has freely given it to his Countrey.

‘Read therefore the book,’ he wrote. You will find yourself taken captive, ‘but used more kindly by the Author, than he himself was by the Natives.’ Hooke and Knox became close friends. The scientist’s diary refers to multiple meetings and one, late in 1689, at which they discussed the effects of ‘bangue’ (cannabis):

[Tuesday, 5 November 1689] Captain Knox told me the intoxicating herb & seed like hemp by the moors calld Gange is in Portuguese Banga; in Chingales. Consa. tis accounted very wholesome. though for a time it takes away the memory & understanding.

In December 1689, Hooke gave a talk to the Society on bangue, noting that ‘the Person, from whom I received it, hath made very many Trials of it, on himself, with very good Effect.’ Indeed, Knox was a man after Hooke’s heart.[53]