The Early Career of Edward Fenton

The temper of these voyages is defined by the character of their ship, as well as by her officers and crew. The Edward Bonaventure was commissioned in about 1574, shortly after John Hawkins began to influence the Navy Board’s thinking on ship design. Hawkins had a vision of fighting Spain outside European waters, where the treasure on which she depended was more vulnerable. As Sir Walter Raleigh was to argue, it was not the trade in sack, or Seville oranges, which afforded Philip his power to do harm. It was ‘Indian gold’ that endangered and disturbed the nations of Europe, and which loosened the bonds upon which its monarchies depended:

If the Spanish king can keepe us from forraine enterprizes, and from the impeachment of his trades, eyther by offer of invasion, or by besieging us in Britayne, Ireland, or else where, he hath then brought the worke of our perill in greate forwardness. Those princes which abound in treasure have greate advantages over the rest, if they once constraine them to a defensive warre, where they are driven once a yeare or oftner to cast lots for their own garments, and from such shal al trades, and entercourse, be taken away, to the general losse and impoverishment of the kingdom …

Henry VIII’s high-charged ships looked back to an age when England’s principal enemy had been France. Their usefulness was confined to the Channel and North Sea. Their heavy upperworks were unsuited to stormier seas, and so they precluded offensive campaigns on the oceans. And, as Sir Walter noted,

… when men are constrained to fight, it hath not the same hope as when they are prest and incouraged by the desire of spoyle and riches.[3]

Reflecting the new approach, Hawkins commissioned a class of ‘race-built’ galleons, of which the Edward Bonaventure is a fine example. As their name, derived from the French ‘razer’ (‘to shave’) implies, the galleons had sleeker lines than the earlier ships. Their water line length was at least three times their beam, and their forecastle and poop were set closer to stem and stern. They were built for speed and manoeuvrability. Modest in size, they were economical in crew, which created room for victuals, and cargo. Even so, they were well-armed, with heavy culverins, for strength and reliability, and chasers in stern and bow. In 1582, the Bonaventure was said, by Ambassador Mendoza, to be armed with ‘30 great cast-iron pieces’, a figure close to the thirty-one which she was reported to be carrying at the end of her career, in 1594. Service with the Navy in the Mediterranean, at Cadiz, and during the Armada campaign, were to demonstrate that she was better fitted for predatory warfare than for peaceful trade. So, arguably, was Edward Fenton.[4]

He was born in Nottinghamshire, the brother of Geoffrey, later Principal Secretary of State in Ireland. His first command was during the rebellion of Shane O’Neil, in 1566, but it is with Martin Frobisher’s second voyage in search of the North-West Passage that he properly comes into view. First sight of him is of his intervening in an argument between the commissioners of the voyage and their commander. When drafting the terms of Frobisher’s appointment, to cover for the eventuality of his death, they ‘woold have joyned unto him Captaine Fenton and some others of the gentillmen that went with him.’ Frobisher, Michael Lok says, ‘utterly refused the same, and swore no smale oathes, that he woold be alone, or otherwise he woold not goe.’

Therewithall he flonge owt of the doores, and swore by gods wounds that he woold hippe my masters the venturers for it, at which words Captayne Fenton plucked him secretly, and willed him to be modest.

Later, in Baffin Island, Fenton interceded on behalf of Christopher Hall, who was berated with ‘owtragious speaches’ and even threatened with hanging ‘because he spake to [Frobisher] with his Cappe one his heade.’[5]

Fenton voyaged there as captain of the Gabriel but his duties, once he arrived, consisted of looking after the soldiery and using them to impress the natives:

Captayne Fenton trayned the companye, and made the souldyoures maineteyne skyrmishe among themselves, as well for theyr exercise, as for the country people to beholde in what readynesse oure menne were alwayes to bee founde; for it was to bee thoughte they lay hydde in the hylles thereaboute, and observed all the manner of our proceedings.[6]

In the third Frobisher voyage, Fenton was Lieutenant General and captain of the Judith. On 2 July 1578, in the pack-ice in which the bark Denis was sunk and the rest of Frobisher’s fleet imperilled, the Judith became separated and underwent a peculiarly lonely ordeal:

The winde cam south southest with so much winde as the sailes could carie in the bolts. And being thus in daunger of it, we did turne in thize all the night, and in the morninge it did shutt upp altogether, and we were fayne to putt into it. And abowte 4 of the clock in the morninge we were in great daunger to loose Shipp and ourselves (if god of his greate mercie and providence had not wonnderfullie delivered us) after lying thus tossed and shut upp in the ize with muche winde and a greate fogg, after our hartie prayers made to god, he opened unto us (as to the children of Israell in the brode sea) a little cleare to the northwest wardes, whereinto we forced our ship with vyolence …[7]

It was not until 21 July that, having fought off the ice with pikes and oars for three weeks, the Judith forced her passage into Countess of Warwick Sound. It was a courageous effort.

One of Frobisher’s plans on this expedition was to establish an overwintering colony of a hundred men. They were to mine extra quantities of the ore upon which his hopes were set, before a fourth voyage returned the following spring. It would have been the first English colony in the Americas, pre-dating Roanoke by almost a decade, and Fenton would have had the charge of it. The sailor Thomas Ellis commended the ‘stoute stomachs & singular manhood’ of those, like Fenton, who were willing to remain, despite ‘the intemperature of so unhealthsome a Countrie’, the savageness of the people, and ‘the sight and shewe of suche and so many straunge Meteores’. But it was a hopeless idea. What the colony was expected to achieve once winter was advanced it is hard to imagine, and the surviving of it would have made Roanoke a picnic by comparison. Fortunately, the effort was abandoned before it began. A substantial portion of the colony’s prefabricated house was lost with the Denis and, although Fenton offered to stay behind with fewer men, it was thought impossible to adapt its remains before it became necessary to depart.

Fenton satisfied himself with building a small stone house on Countess Warwick Island, as an experiment to see how it stood the winter, and to guide future construction. In it, he placed ‘dyvers of oure countrie toyes’: bells, knives, model soldiers, looking glasses, whistles, and pipes; even an oven filled with baked bread, ‘thereby to allure & entice the people to some familiaritie against other years.’ It was probably the first stone structure built in North America by Europeans. Named ‘Fenton’s Watch Tower’, traces of it remain.[8]

Before the expedition ended, the headstrong commander and his opinionated land general came again to ‘hoat woords’, over the ill-discipline of Edward Robinson, and of Frobisher’s kinsman Alexander Creake. Frobisher took their part against Christopher Hall and Robert Davis, master of the Ayde, even though, through their carelessness, she was bilged by her anchor in a collision with the ice, and almost lost. Thereafter, we are told, there arose such contention between the mariners and the gentlemen that ‘they weare with their weapons to have joyned togethers, had not Captain Fenton wisely pacified that Stryffe by quiet puttinge uppe of the Injuryes.’ These differences were patched over but, when Frobisher was later replaced by Fenton as commander of the Bonaventure, it cannot have given him pleasure, especially as events were to prove Fenton weaker at command.[9]

It was not because Frobisher was thought incapable that he was replaced. Rather, there were doubts over whether he could be trusted to follow the purpose of the voyage. Even after 1580, Queen Elizabeth and Lord Burghley were questioning the wisdom of provoking King Philip. Others – Drake, Hawkins, their Plymouth associates – had few such inhibitions. Frobisher’s instincts were similar. These men’s eyes were set on the pickings offered by the treasure fleets, much less on establishing a base in the ‘Spiceries’. The difference in priorities gave rise to tensions that were to be felt throughout the succeeding voyage.

In fact, Fenton’s cruise was born of a ‘First Enterprise’ developed to support Dom Antonio, pretender to the Portuguese throne, but only acknowledged in the Azores. Recognising the islands’ geographical significance, Francis Walsingham and the Earl of Leicester conceived a plan whereby a fleet would establish a base on Terceira and, from there, seize Spanish treasure ships passing from the Caribbean. A letter of marque from the Portuguese ‘king’ would provide the necessary diplomatic cover.

In addition, the sponsors noted, the fleet might collaborate with the Portuguese further afield:

This company of shipes may spend the tyme abowt the Ilonds untyll thend of September waytyng the coming of the flete from the west Indies, yf those shold be myssde then maie the hole fleete range all the cost of the west Indyes and sacke all the townes and spoyle whersoever they fynd them by sea or land.

(The section in italics was heavily scored through by Burghley.)

The same ships with ther fornyture & vitalls are a fytt proporcyon to go to the Callycut (Calicut) & ther to establyshe the trad of spyce in her Majesties right as a party with the Kyng of Portyngall. That which dothe lode one of the great caraks wylbe suffycyent to lade all the flote so as yf the trad be substancyally settlyd & determyned betwixt her Majestie & the Kinge, our owne shipes may come home loden with spyce, & whaftt home any of the caraks that shal be thought meete to come with our shipes.

If the expedition took effect, the promoters argued, fifty ships might be employed in the following year to market English commodities and investigate the trade of the Moluccas and China. But the plan fell through. France, approached for finance and support against the likely reaction of Philip, refused to commit herself unless Elizabeth married the Duc d’Alencon, the suitor she dubbed her ‘frog’. This she would not do.[10]

At the beginning of September 1581, the Earl of Leicester promulgated a more modest scheme. It was based on a plan for an expedition to the Moluccas suggested, in January, by Drake. (Leicester subscribed £2,200, Sir Francis £666.13s.4d.) A private venture might be disowned by the Crown: it bore fewer constraints on behaviour should a laden carrack cross its path. Still, official doubts crept in. In troubled times, it was a risk for Drake to be absent for long. Also, if he went, could he be trusted to keep the expedition on course?

Frobisher was asked to take his place, with Edward Fenton and Luke Ward in subordinate positions. (Ward, like Fenton, had served with Frobisher at Baffin Island.) The crews included a dozen, among them John Drake (Sir Francis’ nephew), ‘Young’ William Hawkins (Sir John’s nephew) and the senior pilots (Simon Ferdinando and Thomas Hood), who had been on Drake’s circumnavigation. Reflecting the nervousness entailed by their inclusion, Leicester was advised that, if a character such as Hawkins were to serve, ‘some other trusty, not alltogether to be ruled by him, be joyned in shippe with him.’

For five months, and with some enthusiasm, Frobisher coordinated the preparations. Then, in February 1582, he was discharged, and Fenton was put in his place. No explanation is given, but Burghley had involved a committee of Muscovy Company men in the organisation of the venture. Probably, they applied the brakes on the freebooters. (This is what Mendoza believed: he claimed to be ‘inciting the quarrel.’) That Frobisher was suspected of siphoning off expedition funds may have been the precipitate reason for his ejection, but committees were not matched to his temperament, and he possessed too much of the Drake spirit for the comfort of Burghley.[11]

Fenton’s record in the Frobisher voyages had been an honourable one, but he was more soldier than sailor, and his appointment was not popular. In March 1582, Henry Oughtred, one of the main sponsors of the voyage, and a supporter of William Hawkins, wrote indignantly to the Earl of Leicester about his protégé being required to serve under Fenton:

Mr Hawkyns … [is the chief] hoope of the viyage, butt withall I [find you have] made him an underlyng to one who ys [without] knowledge, which att the sea will make great dis[content], his experience is verye small his mind hyghe, his [temper] of the manne colerick, thrall to the collyck and s[tubborn] … I [think] his service wil be verye small and yet his mynde [ho]te as not to be overruled, which woll make great dyscord in owr [company].

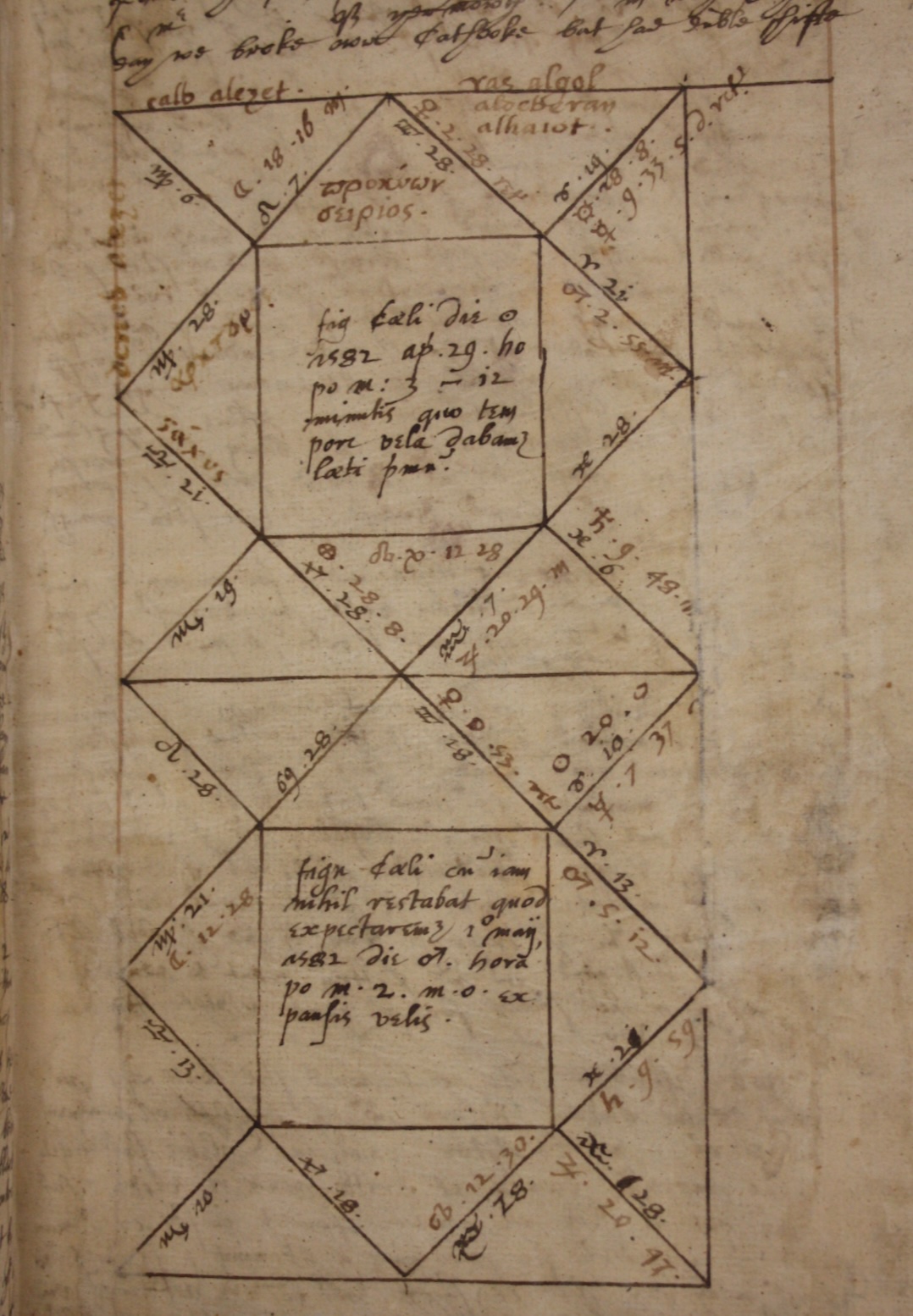

Fenton had married Thomasine Gonson, the younger sister of Sir John Hawkins’ wife. Conceivably their association contributed to the development in him of a ‘hyghe’ attitude towards William. Certainly, they resented each other’s company. Yet, there was more bad blood than this. At Plymouth, Fenton attempted to sail and leave the entire Drake contingent ashore. He claimed that ‘he had better men wythinborde than anny of those’, so it was humiliating for him when they caught up with the fleet, and he had to receive them back. Nor were the Drake party Fenton’s only critics. On 29 May 1582, as the Bonaventure stood off Torbay, Richard Madox, whose diary is one of the principal records of the voyage, wrote that Alderman Barnes (significantly, a Muscovy Company man) judged Fenton ‘a folish, flattering, fretting creeper.’ ‘So I fear he wil prov,’ Madox added.[12]

The Troublesome Voyage of Edward Fenton (1582-1583)

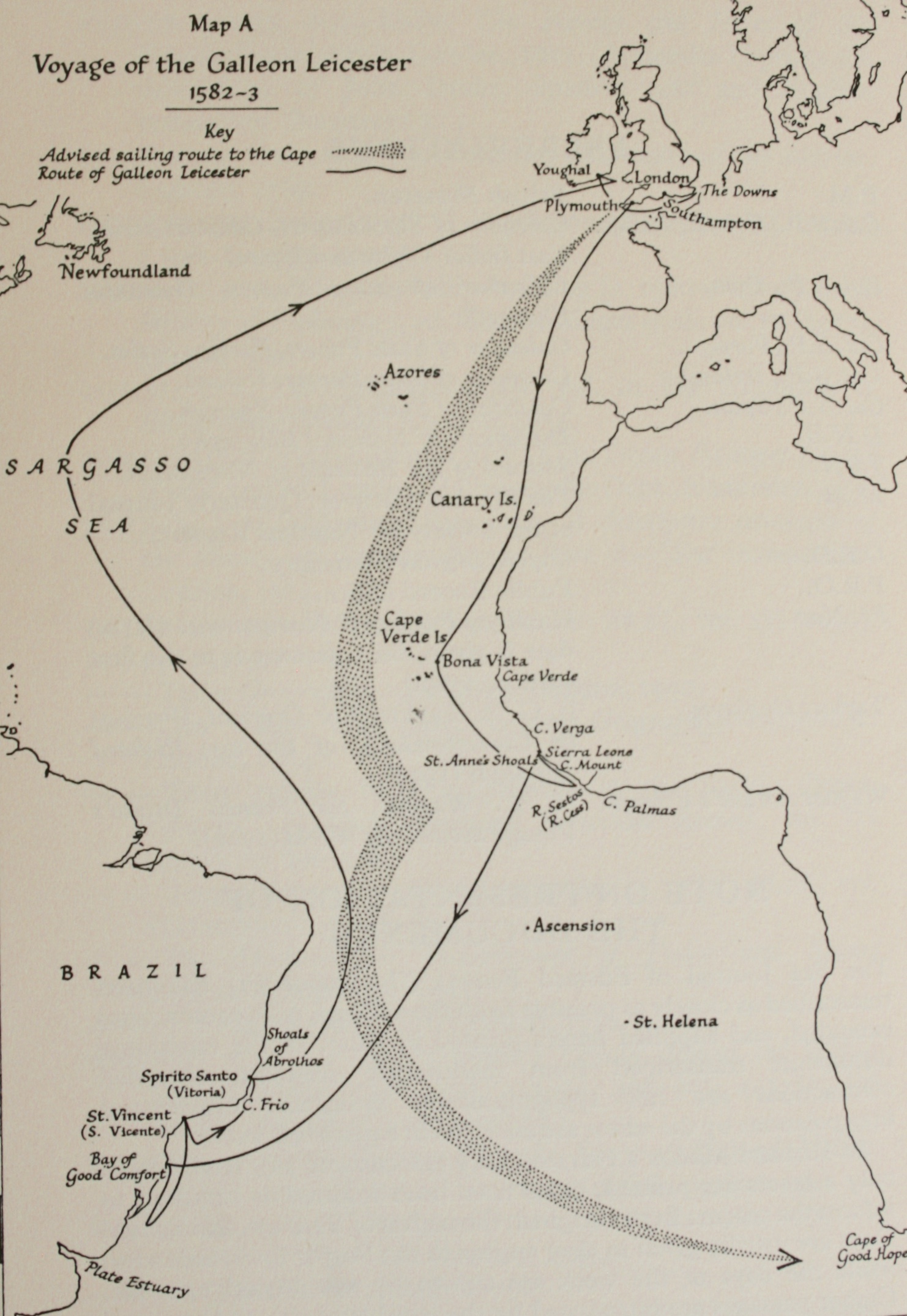

Fenton’s instructions were issued on 9 April 1582. The fleet was headed by the Galleon Leicester, under his command, with William Hawkins as lieutenant and Christopher Hall, the veteran of Baffin Island, as master. The Edward Bonaventure was captained by Luke Ward, the barque Francis (forty tons) by John Drake, and the pinnace Elizabeth (fifty tons) by Thomas Skevington.

Ambassador Mendoza reported to his king that the Leicester displaced five hundred tons and carried a complement of two hundred men and seventy cannon. The Bonaventure, he claimed, was of three hundred tons and crewed by one hundred. The Francis carried a crew of thirty-five. These were overestimates. In fact, the Leicester had 120 men (forty-two cannon) and the Francis’ crew was seventeen. According to Madox, the Bonaventure had a burthen of about fourteen score (280) tons, and a complement of eighty, of whom around twenty were ‘necesarie men’ and boys, rather than sailors. Some, he says, were to be used to man the Francis. Nonetheless, the principal ships were young and modern. The size of the force belies the peaceful purpose contained in Fenton’s instructions that its officers ‘deale altogether in this voiage like good and honest merchants.’[13]

At the outset, Fenton was given ‘absolute power and authoritie’ to ‘order, rule, governe, correct, and punyshe by imprisonment and violent meanes and by death’ the entire company at his command. His instructions required him to consult on important matters with a Council of Assistants, but events were to show he had as little inclination to listen to the opinion of others as had Drake and Frobisher. He was not their equal. His bluster covered for irresolution, and such consultations as were held tended to indecision and acrimony rather than to good planning and harmony.

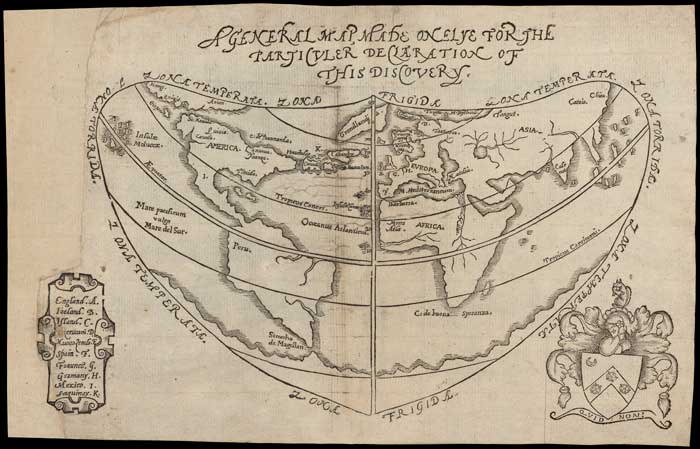

On the matter of the route, the instructions were unfortunately, perhaps deliberately, qualified. The intention was clear: Fenton was to take his course for the Moluccas via the Cape of Good Hope. Yet the wording, that the Straits of Magellan were to be avoided ‘except upon great occasion incident, that shall be thought otherwise good to you, by the advise and consent of your sayd Assistants’, provided room for interpretation to those who were determined to look for it.

The destination was also imprecisely defined. According to the Queen’s ‘broade seale’, the expedition was directed,

… into foreyn parties to the southeastwards as well for the discovery of Cathaia & China, as all other lands & yslandes alredy discovered, & hereafter to be discovered by Edward Fenton.

Fenton was enjoined not to ‘spoile or take anything from any of the Queens Majesties friends or allies, or any Christians’, but for those minded to steer for the Straits, the Spanish (and now the Portuguese) were neither friends, nor allies, nor the right kind of Christian. The idea of despoiling them was never far from their minds.[14]

As early as 24 May 1582, when the Bonaventure stood off Dartmouth, her master, Thomas Percy, told Madox, the Leicester’s minister, that ‘he supposed the viag wowld have turned to pilfering.’ When, a little over two weeks later, the crews spied a merchant ship off the Portuguese coast, she was duly seized. She turned out to be a Flemish hulk and was released, Madox using his sermon the next day to criticise the attempt. To his private diary he confided,

… they wer al withowt pytty set upon the spoyl. After noone Capten Ward and M Walker cam to us and told how greedy they wer and espetially M Banester, who for al his creping ypocrysy was more ravenowsly set upon ye pray than any the most beggarly felo in the ship, and those also which at the shore dyd cownterfet most holynes wer now furthest from reason affyrming that we cold not do God better service than to spoyl the Spaniard of both lyfe and goodes …[15]

It had been Frobisher’s intent to be at sea by the Christmas of 1581. Fenton did not leave the River Hamble until 1 May 1582. In adverse weather, he then spent twenty days crossing between Yarmouth and Cowes. There followed the quarrel at Plymouth, in which he attempted to leave behind the Drake party. It was not until 1 June that the fleet lost sight of the Lizard and, by then, the season was getting late for clearing the Cape.

At a council held off the Barbary Coast, on 24 June, it was agreed to take on water at Bona Vista, in the Cape Verde Islands. The pilots were then asked what the next destination should be. Their answer was the River Plate. John Walker, chaplain on the Bonaventure, saw that, whilst it was wise to steer well to the west of the ‘vallanows’ African coast, this was going too far. He objected that,

… being come thither wee shold be carried ether by necessyty or by pretences, agaynst our commission to passe throwe the straytes of Magellanus whereunto he saw many throe desyre of purchase as they cawl yt, much enclyned.

To the pilots, Ferdinando and Hood, ‘purchase’ meant ‘plunder’, not ‘trade’. However, Walker’s objections were answered with ‘wyndes and tydes and currents and reconyngs’. He yielded to those more expert than himself.[16]

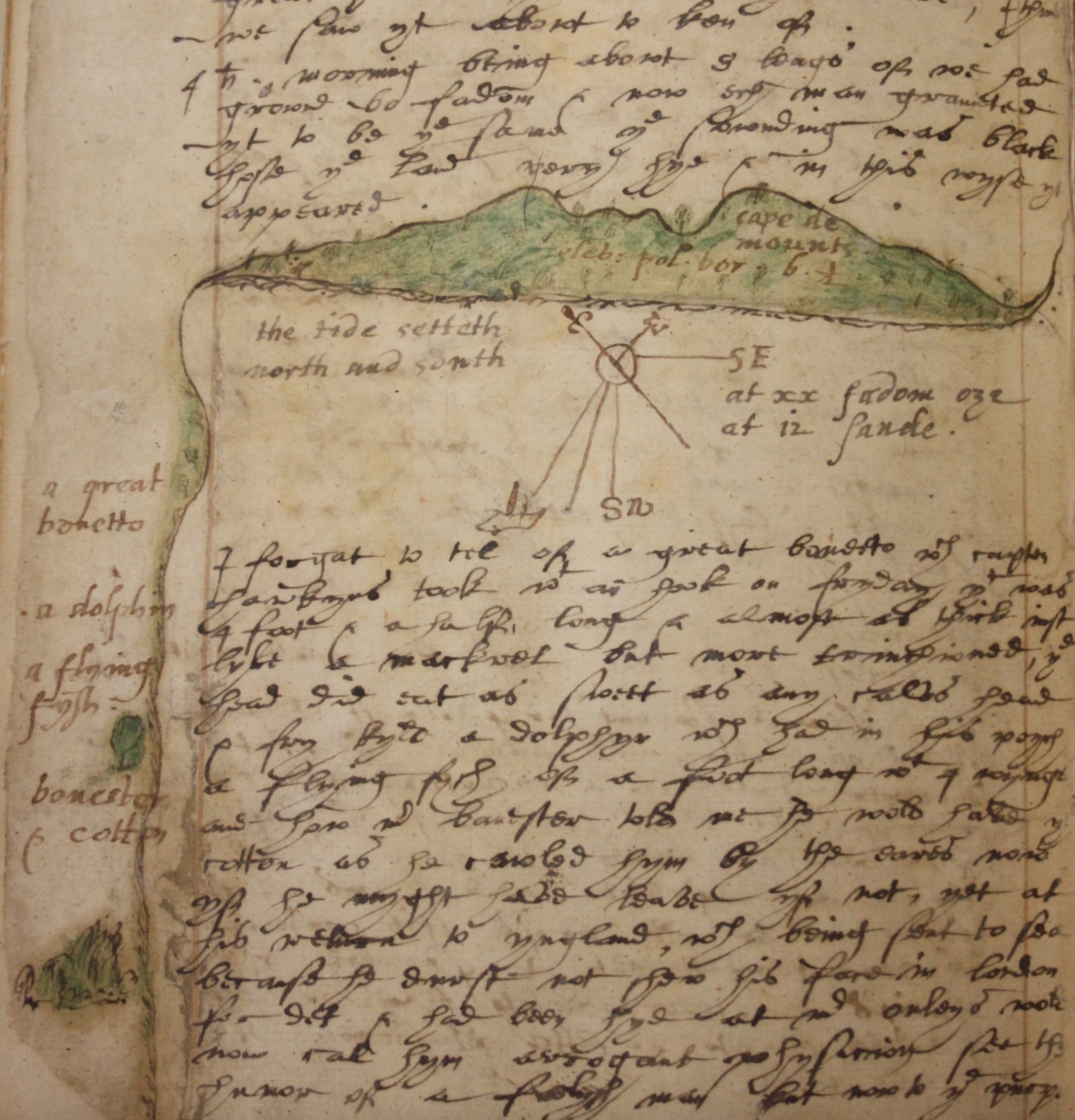

At Cape Verde, which ‘some sayd was Bonavista but others thowght yt was La Sal but none cold tell’, Luke Ward found a river for fresh water and, for food, numerous goats and birds, an abundance of fish, and ‘monstruows great tortuses’. But Fenton, encouraged by Nicholas Parker, the commander on land who, according to Madox, ‘thowght every crib (hovel) a castle and every gote an armed soldier’, determined time was too short and the swell too great to permit revictualling. For this decision, which was criticised ‘with gawdy words’ by the captain of the Elizabeth, Madox thought Ferdinando was chiefly responsible. His argument was that ‘for want of water we myght robb.’

Having taken this risk with the stores, the fleet steered to the south-east, to catch the easterly wind from Guinea. But the wind died, and they spent the best part of another month aimlessly tacking about the coast of Africa, as the pilots argued about where they were, the supplies diminished, and the crews grew sick. Thomas Hood, ‘with a bawling mowth’ gaped ‘for the Spaynysh treasures swaloyng up the men and spoyling them of ther money alyve’, while Madox prayed the Lord would ‘stay the rage of our syn that yt be not repressed with the rigor of his fury.’[17]

On 20 July, another council was called to fix the fleet’s location, there being some dispute as to whether the promontory then in view was Cape Palmas or Cape Verga. (These are some eight hundred nautical miles apart). According to Madox:

Mr Whood sayd the land we saw was Capo de Palmas or els hee wold fyrst be hanged and after cut in 1000 peeces. Such an insolent spech men wold not for modesty sack crose, althogh ther wer reasons to the cuntrary.

There was a consultation. Should they sail onward to the east or back to the north-west? William Hawkins interjected. The further east they travelled, the further they would be from the Plate. Better, he suggested, to seek out Sierra Leone. Whether they were becalmed or not, at least they could harbour in safety. Fenton was unpersuaded. Madox reports,

… that he feared the health of his men because al had spoke yl of the cuntrey, but the very truth was, he feared lest fynding ther suffyciency for our provision, he shold have than no pretence to passe to the westward …[18]

For now, Fenton was overruled. The council settled on Sierra Leone – a decision that was taken for a second time on 1 August, after another fortnight of fruitless sailing. The fleet finally dropped anchor on 9 August 1582. At Sierra Leone it remained until 2 October, as antagonisms between the officers intensified.

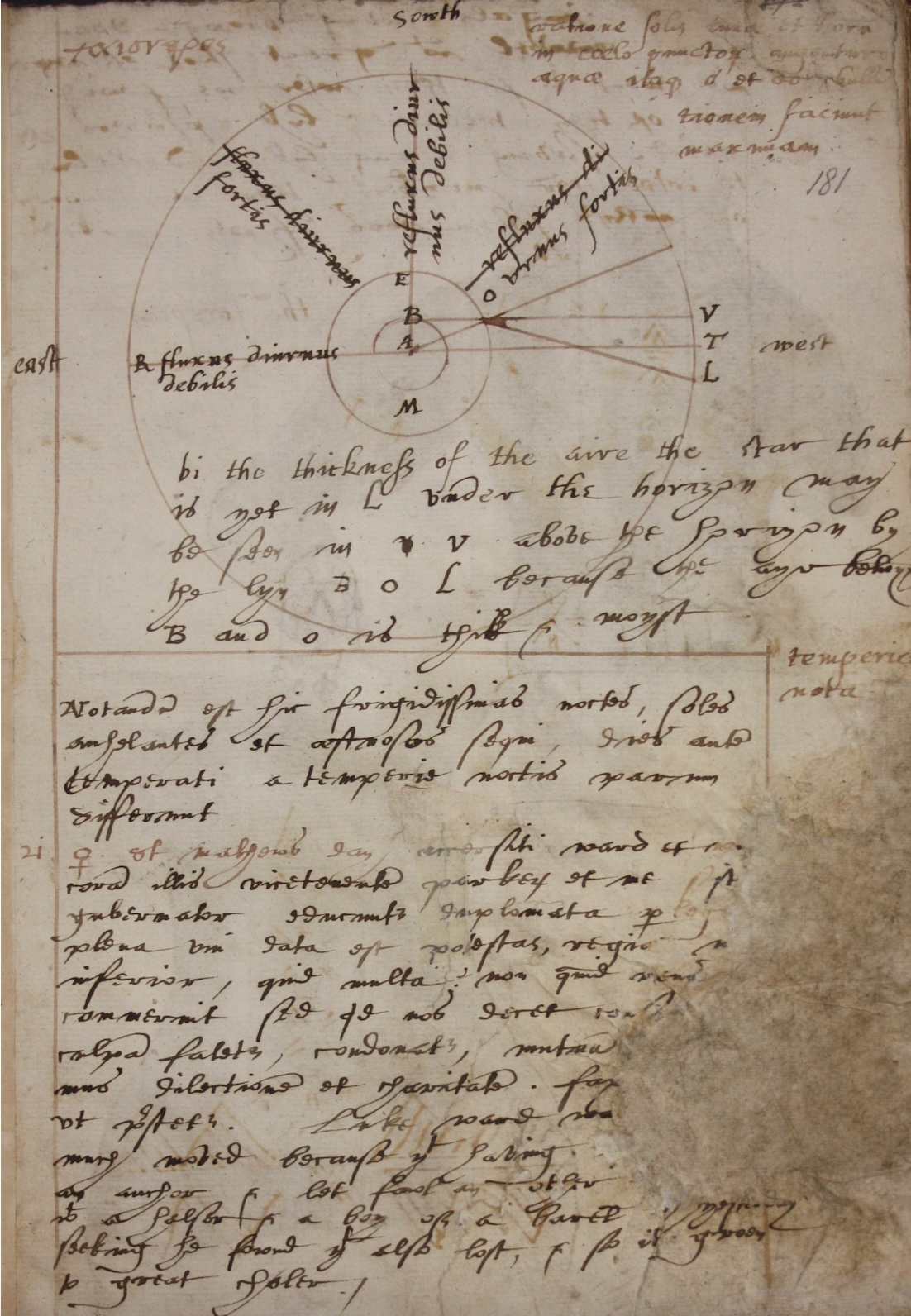

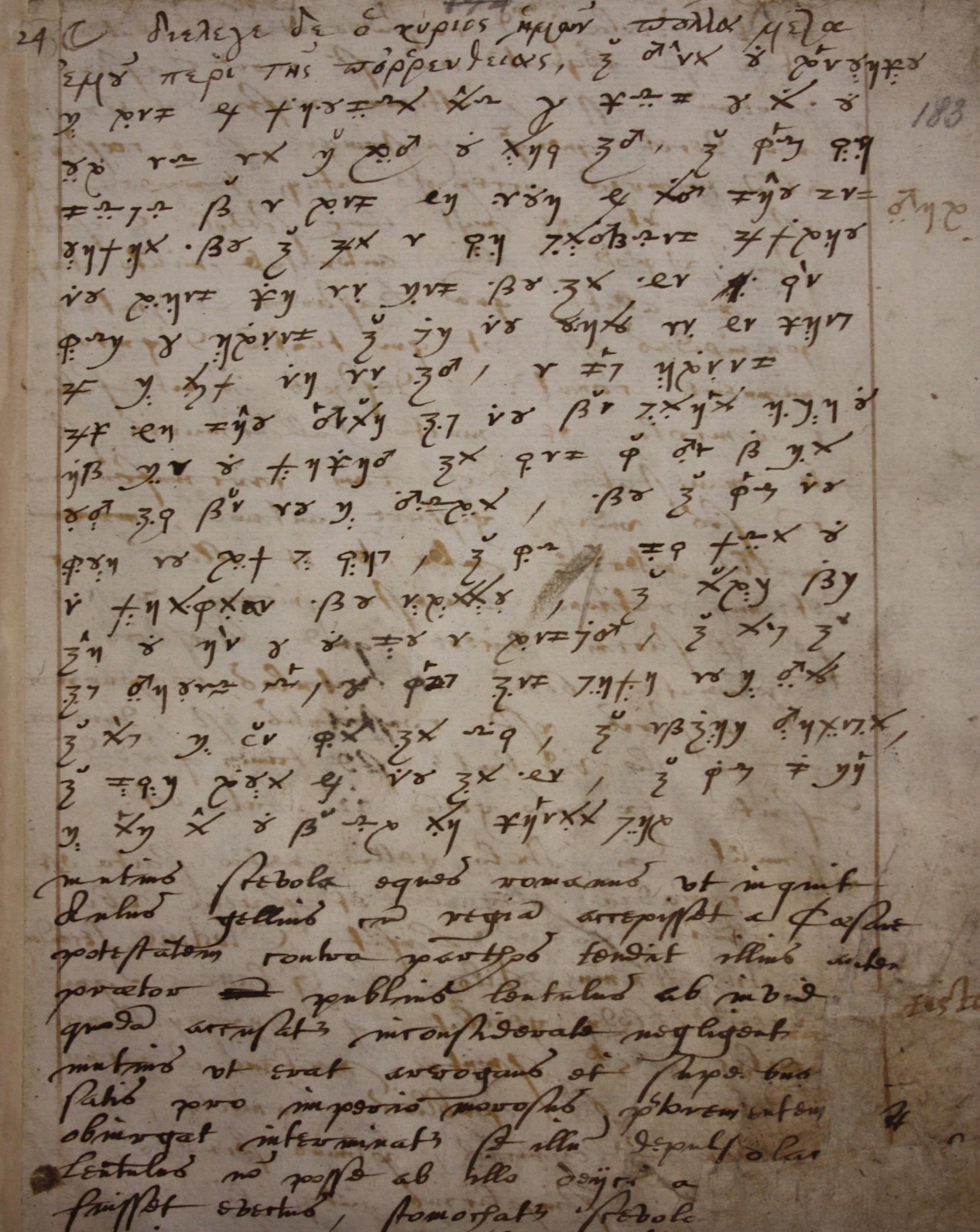

By now, Fenton had intercepted one of Madox’s letters to John Walker. Not being able to interpret its Latin, he had become suspicious of ‘secrett practyses’, even that his chaplain might emulate Francis Fletcher, the priest who, during the Golden Hind’s circumnavigation, had criticised Drake’s execution of Thomas Doughty, and had been chained to a hatch cover and ‘excommunicated’ for his trouble. Hereafter, Madox regularly used a personal cipher, as well as Latin and Greek, in the writing of his diary. To muddy the waters further, he gave the officers names from Roman history and literature, none of them flattering. Fenton became ‘Clodius’, Luke Ward ‘Milo’, Hawkins ‘Glaucus’, and Parker ‘Pyrgopolynices’ (Plautus’s Miles Gloriosus). Under this cover, Madox lets us know what he really feels about them: Clodius was ‘clever, deceitful, peevish, greedy, ambitious and of mean spirit, timid and suspicious’; Milo ‘great in words and sufficiently crafty, bold as well as hardworking, irascible, inexorable, grasping’; Glaucus ‘stupid and indiscreet, very boastful … who could not endure Clodius’; Pyrgopolynices ‘a swellhead on account of his charge of soldiers … a very dull intellect.’[19]

Of the remainder, none were less happy than the officers of the two smaller barques, Francis and Elizabeth. John Drake believed his ship was being kept deliberately short of supplies – the consequence of Fenton’s fear she might desert – and he frequently complained of her treatment. Skevington, captain of the Elizabeth, whom Madox considered ‘a fyzzeling talebearer and a pykethank’ had fallen out with his Master, Rafe Crane (‘a hasty foolysh feloe of his tung’), as well as with Fenton. (Crane should have realised that telling Skevington what he thought of Fenton was foolish; for his pains, he spent time in the bilboes.) [20]

As the squabbling echoed around the bay, the English spied an approaching ‘canow’, an event that caused much ado, and sent Parker into a spin. To his relief, the small craft showed a flag of truce. To Madox’s chagrin, so did the Bonaventure:

… as God shal help me, this ship is able to beat the kyng of Spayns fleet, now one sylly canow doth make them creepe into a mowshole. When al was com yn, yt wer 3 sylly Portingales in a lytle swynes troe [boat], the one a sage old man in a capuchio (hood) of black moccado (inferior wool) and shipmens hose of a barbers apern …

The old man was Francis Freer, a Venetian now living at Santiago, the largest of the Cape Verde Islands. He had come off worst in an encounter with a Frenchman, and his ship had been ‘broken agenst a rock.’ He was accompanied by another elderly fellow and Jasper de Wart, a ‘leeger’ (lançado) from Lisbon, who had secured trading rights from the nearby king. Strangely, Madox remarks, ‘His bad cote was noe more patcht than wer his bare legs splotted [spotted].’[21]

These men were a font of information about the natives. King Farma, they said, was accustomed to eat the concubines with whom he spent the night, if they were less than wholly pleasing, but, given a cask of wine, he would provide a month’s worth of rice, fish, fruit and other food, to say nothing of gold and other trinkets and baubles. Despite this advice, Fenton refused the merchants permission to trade. When they sold cloth and pans for double their value, he disapproved, arguing more could be had elsewhere, and ignoring the possibility, as Madox thought, that ‘to have caried some of our perished ware up into the cuntrey … had been both pollytique and gainful.’[22]

Fenton would treat only with the Portuguese. Indeed, to them he sold the Elizabeth for eighty measures of rice, ten quintals of elephants’ teeth, and an ‘Ethiopian’. His restrictions so exasperated the merchant Miles Evans that he abandoned the expedition and returned to England, accompanying Francis Freer in the Elizabeth. To his diary, Fenton confided that the rest were glad of his departure:

… in respect of his stubbardness and mutinous disposition & other vile practizes [it] was yelded unto by us as a thinge most necessarie for the quiet of all the accion.[23]

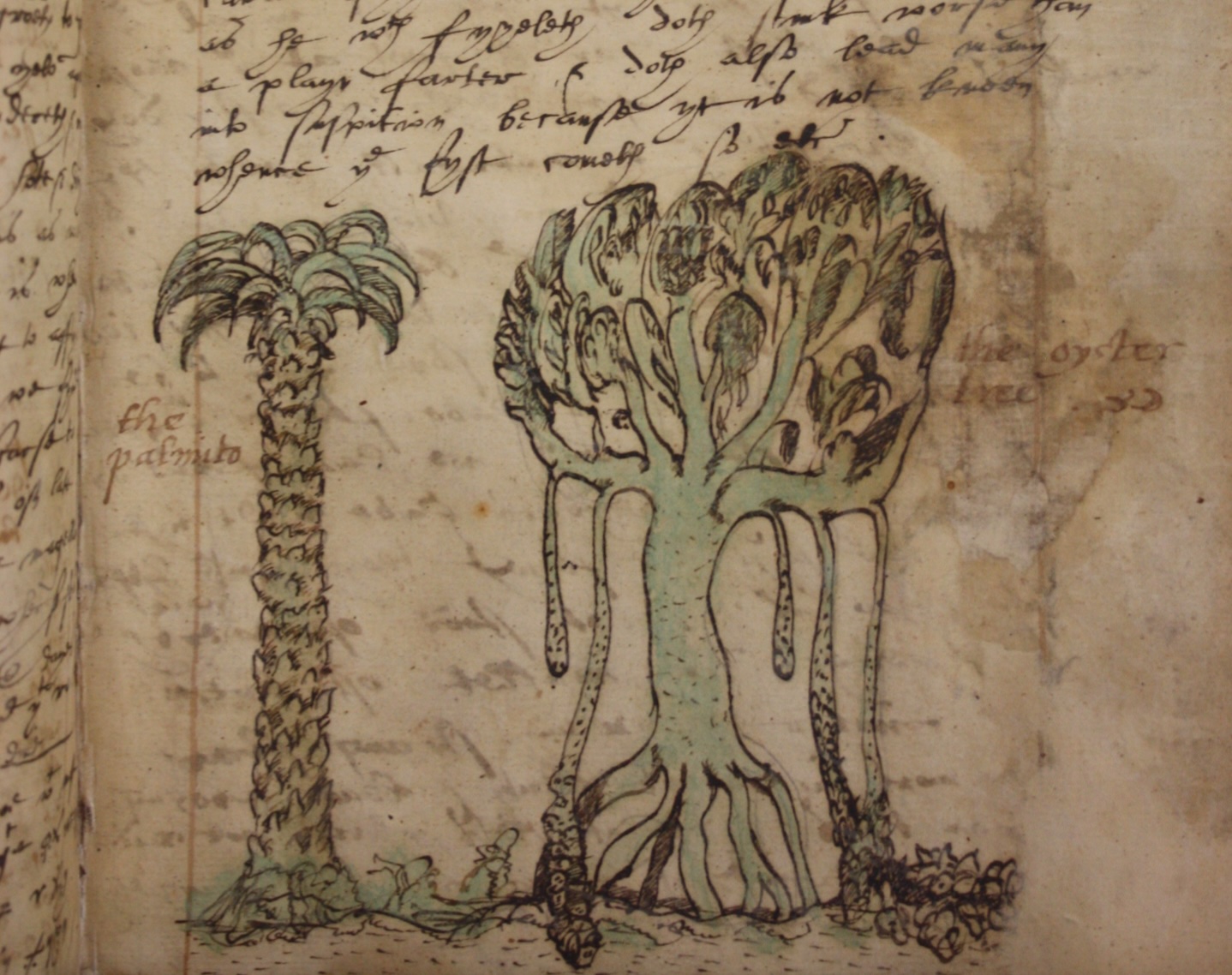

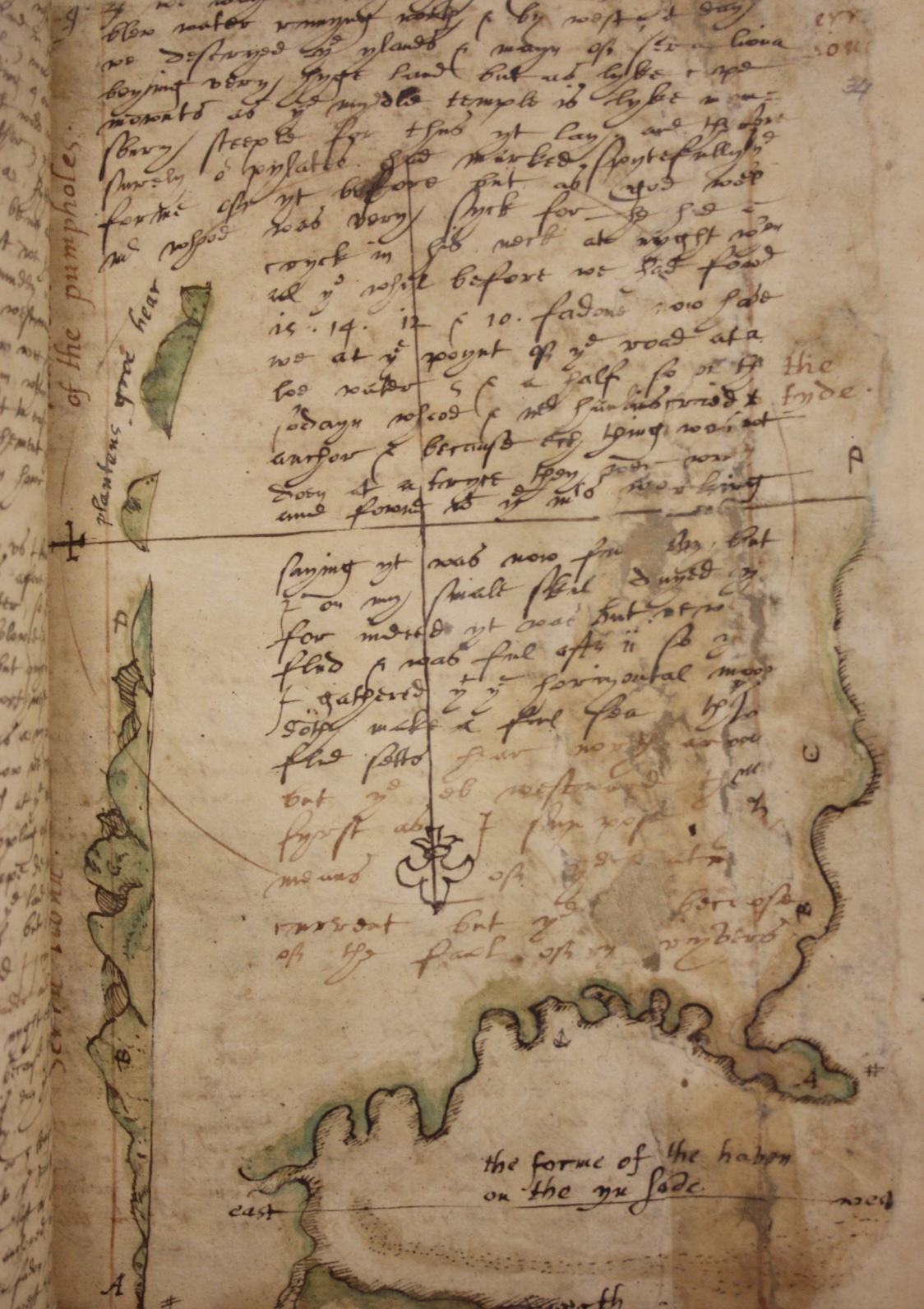

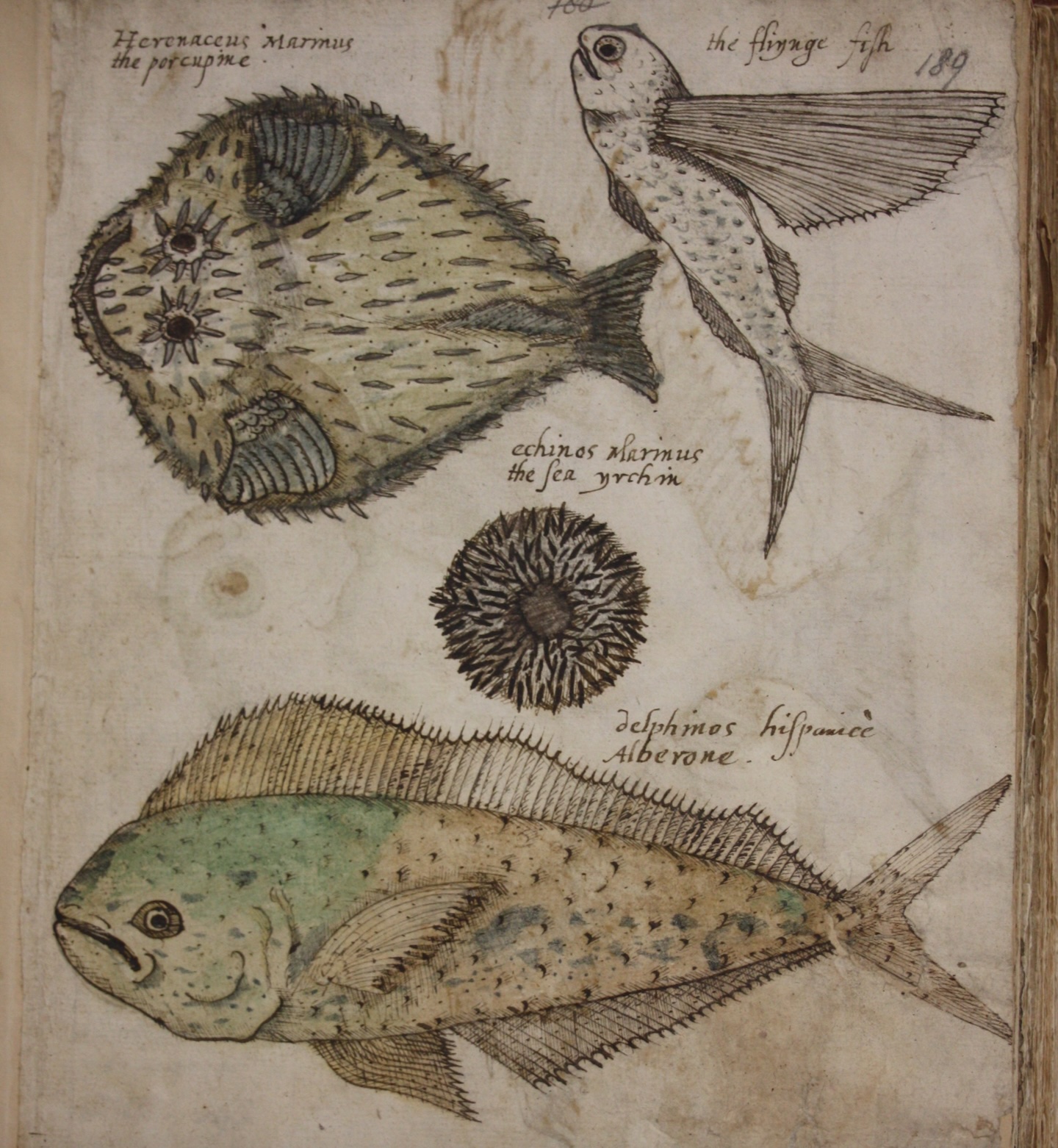

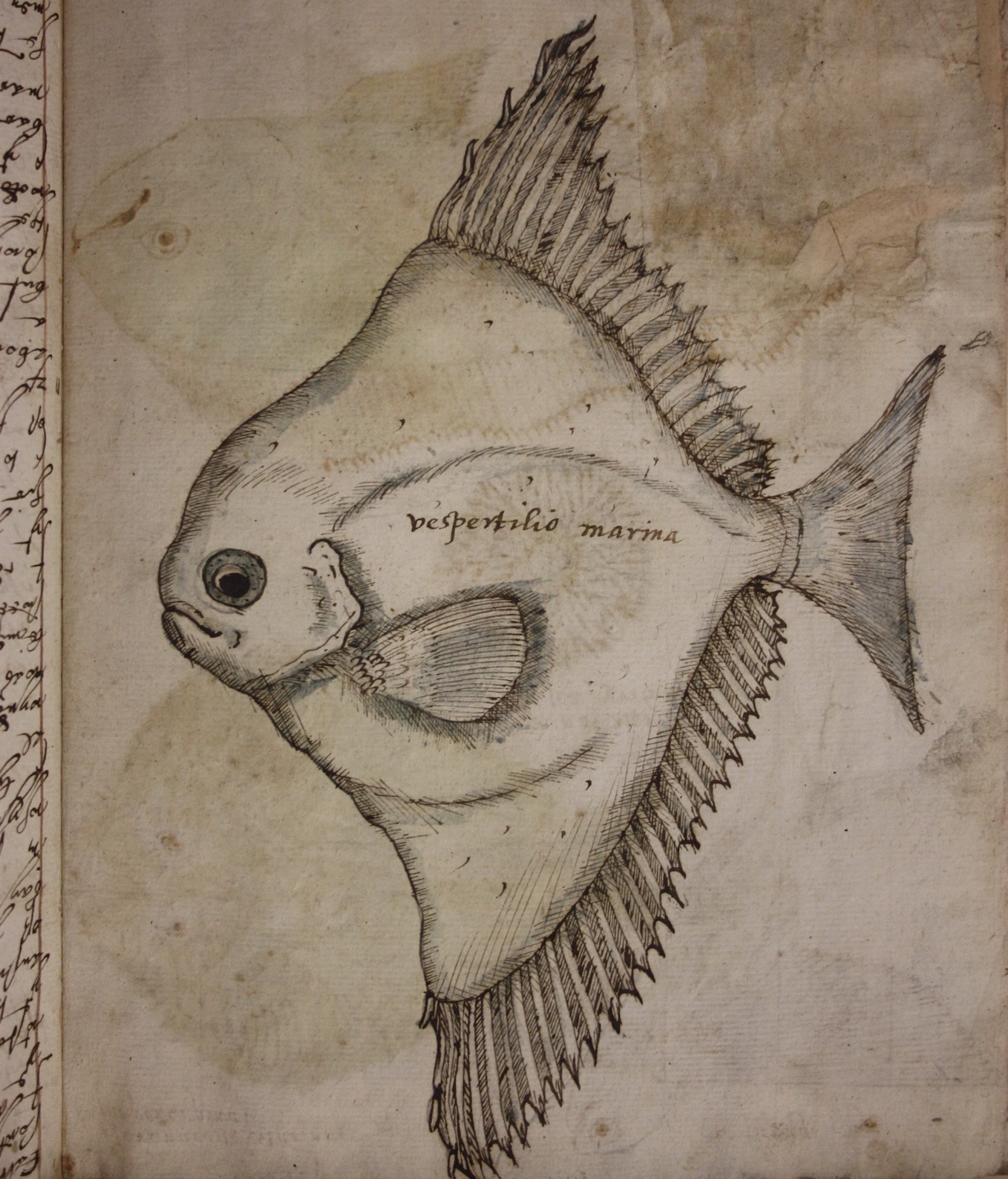

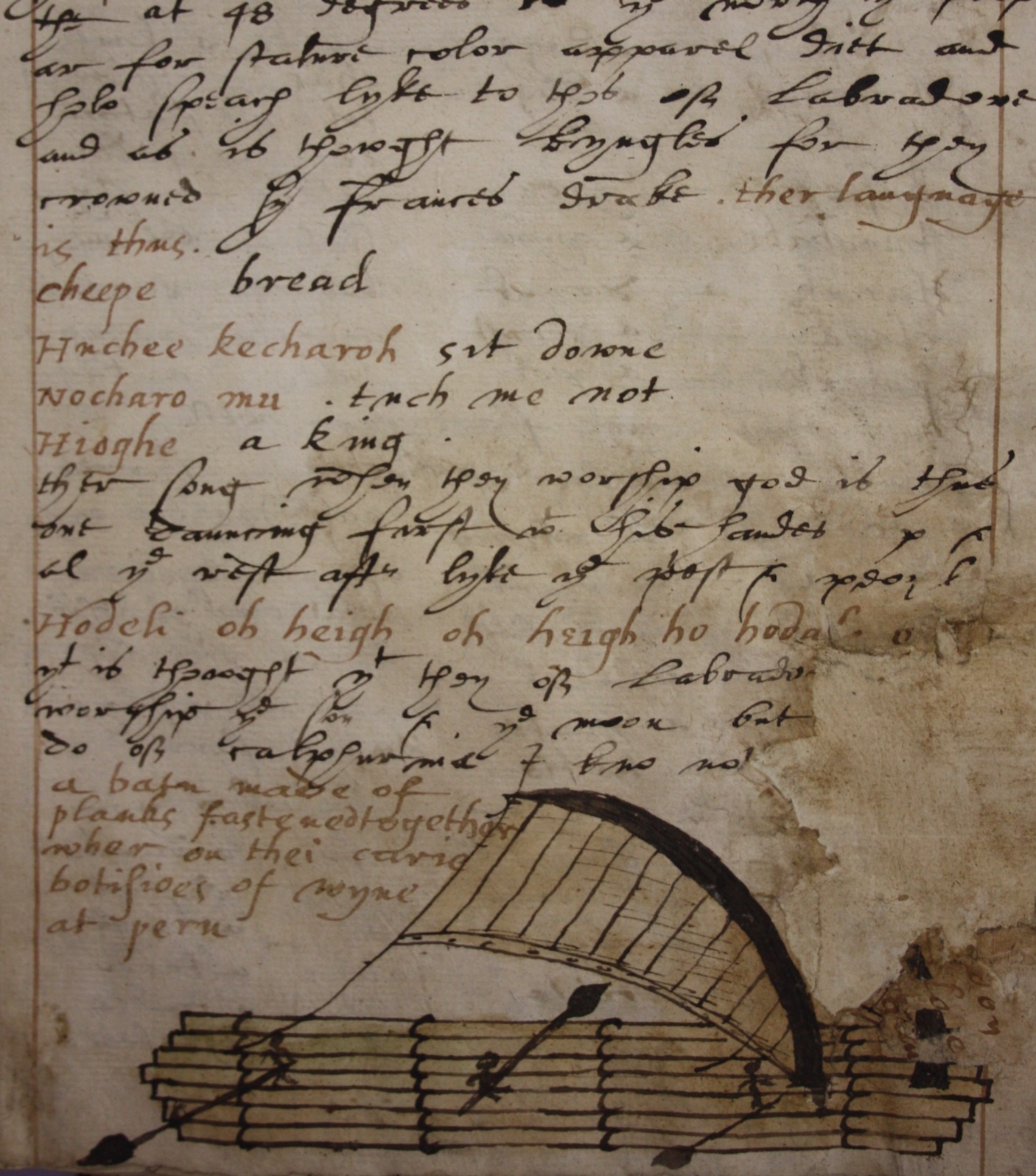

In the meantime, Madox, Walker and the others investigated the country’s flora and fauna. They collected oysters from the roots of the mangroves and measured the ‘fewms’ (droppings) of the elephants. One evening, the crews dined on a sawfish which had come off worst in an encounter with a crocodile. Ward kept its head, ‘in whose nose is a bone of two foot long like a sword with three and twentie pricks of a side, sharpe and strang.’ They also caught in Ward’s fishing net, ‘a Sea-Calfe (as wee called it) with haire and lympits, and barnacles upon him, being seven foote long, foure foot nine inches about.’ This caused some excitement, and Ward summoned Fenton, Madox and others to take a look. The conclusion was that the beast ‘was oughly being alive’, but once it had been ‘flayed, opened and dressed, [it] proved an excellent, faire and good meate, broiled, rosted, sodde and baked, and sufficed all our companies for that day.’[24]

Fenton considered what to do next. One idea was to return to the Cape Verde Islands and restock on supplies, especially wine. Fenton had heard that a dispute had arisen between Dom Antonio and the bishop governing Santiago. ‘Thus,’ he suggested, ‘while favourably inclined to one side, he could seize the opportunity to attack the other.’ Another plan was to sail to St. Helena. This was fertile, free of inhabitants, yet suitable for settlement. Moreover, it was likely that the spice-laden Portuguese would use it to water their ships as they returned homewards the following May. The idea was to fortify it and await their arrival.[25]

By now, Fenton would consult with no one ‘except those who would smile at him.’ To win support, he handed out fresh clothing, ‘but not at his own expense.’ (Walker speaks of new liveries of popinjay green.) Despite his mistrust of them, however, Fenton opened his mind to Madox and Walker, hoping to secure their influence in council. They disobliged. On 24 September, just before a meeting of the council, Madox wrote of his commander,

He wowld very gladly be a king or autor of som great enterpris but he is a very disembling ipocrit, not caring for any thing but his oun vayn welth and rekoning.

Madox reckoned that, had ‘our great mownseer’ (monsieur) been less fixated on robbery, and more solicitous for his mission, the fleet might already have reached the Moluccas. His refusal to water at Cape Verde was characteristic. Failure to take advice, or to plan, repeatedly left him in the grip of necessity. Yet,

He seeketh both hear to rayn and to get a kingdom. He sayd he had martial lau and wowld hang Draper (steward on the Leicester) at the mast. He sayd the queen was his lov. He abhoreth merchants. He giveth cotes of not his oun. He wold go throo the Sowth Sea to be lik Sir Fraunsis Drak.[26]

After consultation, Walker, Ward and Madox agreed that a return to Cape Verde should be resisted at all costs. To go back, Walker exclaimed,

… were not only an overthrowe of our whole voyage but suche and so greate a dyscredyte to the churche of God and my professyon that the enemye myghte have greate cause of tryumphe to heare that 2 professours of the gospell shoulde in so noble action become pyrates …[27]

He later informed William Hawkins that Fenton was promising great rewards to those who supported his plan for St. Helena: £10,000 to Ward, £5,000 to Parker, £2,000 each to himself and Madox. The amounts were to be funded from the capture of the Portuguese carracks ‘if he colde.’ Fenton and his acolytes, he complained, had never had the Moluccas in mind. They had determined on another voyage, ‘which sholde be more profytable (as they deemed) and of their own devising.’ Hawkins might have agreed, but he was unimpressed. Acerbically, he commented,

… that would be a good voyage of their device wch never weare out of the sight of their owne chymbneys, or from their mothers pappes in respect of voyaging.[28]

At the council itself (from which the merchants were excluded), Fenton openly argued against the Moluccas, mentioning ‘some extremytyes lyke to happe for wante of foode.’ Hood agreed, suggesting that the cost of victuals would be excessive, and the supply of spices too small: the people there ‘esteemed nowght but the best silk and fyn linen.’ On this, there was heated argument between Parker and Hawkins, the record of which Madox was told to destroy. (Madox was convinced that Hood’s only interest was in robbery.) Hawkins was ‘all at a venture’ but, with his support, and Ward’s, the chaplains won the argument for adhering to the mission. Fenton then,

… propownded this question … what Course, was thought most fitt to hold aswell to accomplishe the voyage, as relieve our victualls (and the winde contrarie to go by Cape Bone Esperance;) it was thought by all their Consents that to performe thaccion and provide for all wants, the Straits of Magelan was the onlie way, which by thadvise of Tho: Hoode & Blaccoller pilots was fullie aggreed upon.[29]

On 1 October 1582, the fleet weighed anchor.

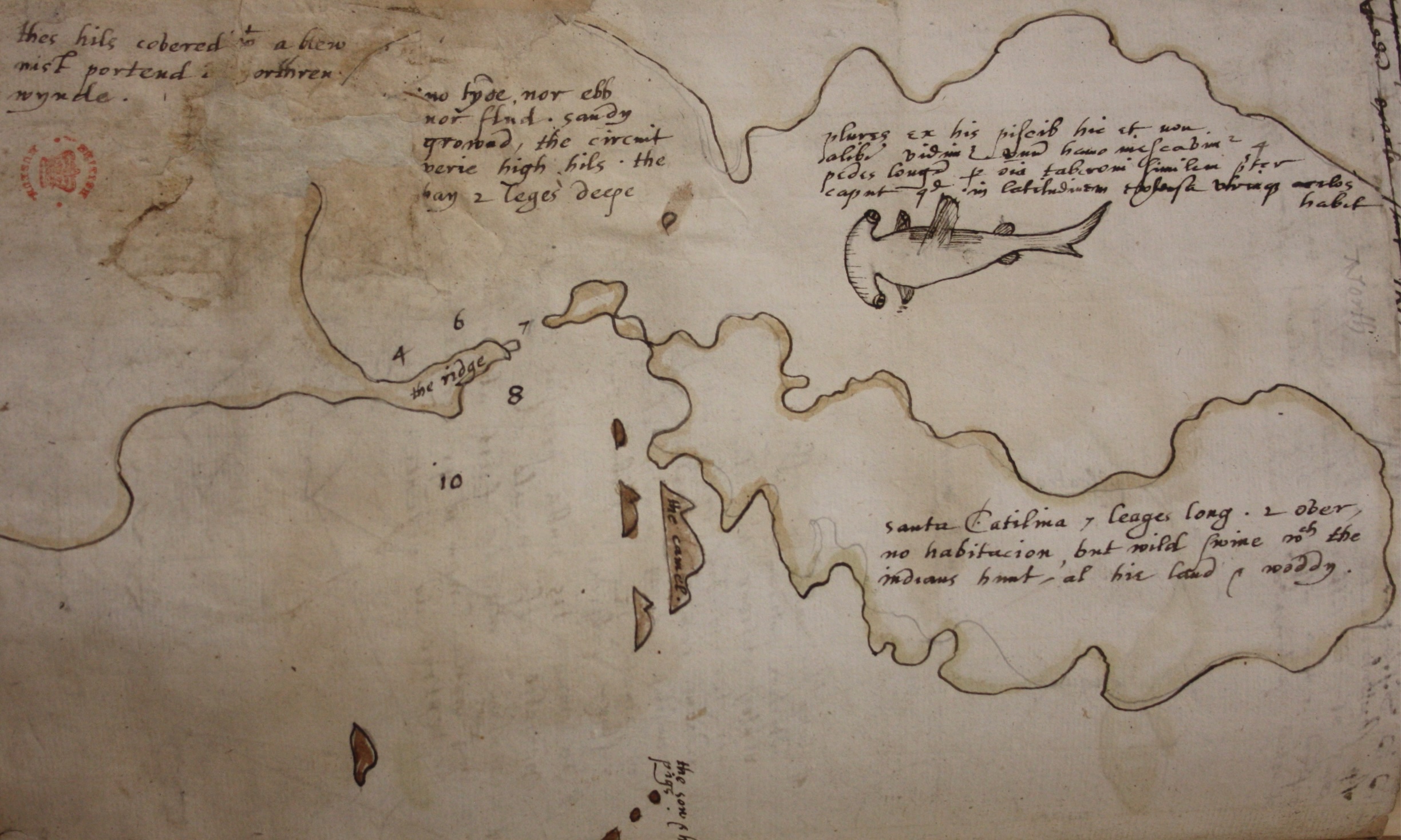

The crossing of the Atlantic was long, but relatively uneventful. At a council on 1 November, Ferdinando suggested that ‘what so ever comes fro the Sowth Sea paseth throo the Bay of Mexico and therfor as good steal it hear as thear.’ He was overruled and they maintained their course for Brazil. Walker, who fell dangerously ill, at one time informed the ministering Madox that Fenton had been prepared to turn his guns on the Bonaventure and Francis, for fear they would desert him. Soon he was calling upon the Almighty ‘to be freed from this prisonhouse before he should see … the hands of all of us shamefully defiled with blood and plunder.’ But he survived, and on 1 December, land was sighted at a place, near Isla de Santa Catarina, which Fenton called the Bay of Good Comfort.[30]

The crews’ failing health was quickly restored with the fruits of Captain Ward’s arquebus and fishing net (the white storks were ‘thin’ but ‘delicious’, the mullet plentiful). Then, amid great excitement, a ship was sighted. It contained a party of friars bound for the River Plate with Don Francisco de Vera, nephew of the Spanish governor for the region. Madox writes,

At daybreak Hypegemon (Ward) approaches us. He points out a ship going by. Good God, what an uproar, what a flurry, what a hubbub. Who, how, what? Oh, Ah. Delay is hateful. Undress is dangerous. We put on breastplates. There is ranting and babbling. All devour the prize. Milo (also Ward) and Pyrgopolynices (Parker) are sent out with the skiff attending. They contend about primacy. Great stirring of minds … The prize is brought in, to wit, 7 friars, 2 women, 2 infants, 8 poor souls in a little bark. We exult. But spirits flash and break out into wrath.[31]

There was a heated argument over who should ‘romage the prize’. Next, earnest debate about how to treat the captives. The first thought was to leave them to contend with the natives on shore but, in the end, the council were won over by the senior friar. He ‘wepte bytterly alledginge they wolde be eaten of the Indyes etc.’ Those who had recently boasted that their two ships could engage the whole Spanish fleet could hardly assert the need for the friars’ small boat; nor, indeed, in a bay of such plenty, for their provisions. In the end, they were sent away in peace ‘but still slightly plucked so as to satisfy our rapacious and greedy sailors.’

Of greater import was the intelligence obtained that a Spanish fleet under Don Diego Flores de Valdes had been sent from Rio de Janeiro to fortify the Straits. (De Vera was to cross overland from the Plate to Cuzco, to obtain support for it.) Consideration was given to the implications of this news before, in an effort to lay false information, the friars were given safe passes addressed to Martin Frobisher. These intimated he was at sea with another fleet, and instructed him to leave the friars at peace before hastening ‘to follow us to the Cape of Good Hope.’ Using this deception as an insurance, the English ships steered to the southward.[32]

There were doubts, however. Fenton was concerned that the friars might alert the Spanish at the Straits, and beyond, to the presence of the English. Walker tried to persuade him that ‘they were ygnoraunte of our intentions’, but Walker had been desperate to spare the friars harm, and others had made the English plan all too plain. Fenton’s concerns transmitted themselves to others. Hawkins who, like John Drake, was firm in favouring the Straits, wrote that Fenton and Ward had dissembled, to ‘blynde their companye’ to their real intentions:

For in truthe this maketh the sayinge of some of our companye thought true, which said that this honourable voyage (the more the pyttie) was bought & solde by the Spanyards frends, or themselves before oure coming out of Englande.

By 17 December, Ferdinando was counselling that they turn back to rob São Vicente, north of the Bay of Comfort. Fenton’s fears about the Spanish defences at the Straits were becoming more transparent. Reacting to his doubts, Madox wrote, ‘wher to rob por men was no conshens, now to hurt such as ar able to hurt us agayn is a grudg of conshens.’ It was, he thought, ‘surly a just judgment of God to mak our cowards manifest.’ On 20 December, Fenton summoned his council.[33]

On what should be done, there were almost as many opinions as people. Hawkins was for continuing at all costs. Drake said they should clear the Straits with a good wind, although not without danger, Ferdinando that ‘he was never there and can not tel how the retches lye.’ Ward, supported by Walker, argued that they should re-provision by trading their merchandise with the Portuguese in Brazil and reconsider their options. The merchants, marvelling that it had ever been decided ‘to go this weye wch we were forbidden’, were for the Cape of Good Hope, as originally intended. Madox extemporised before suggesting:

… we must trust thos that kno what is spoyled & what remayneth & what state ye merchandize doth stand. than must we in my conjecture seek by advice wher we may best vent those commodytyes that we have, and return home with an honest account of as lytle losse as may be ether of stock or tyme, in as much as we ar cut of from that hope which in ye begynning and purpose of our viage was of us al conceaved.[34]

Interestingly, even though, in April 1582, Ambassador Mendoza had believed it to be the original intention, there was no mention of missing the Straits altogether and of sailing around Terra del Fuego. During his circumnavigation, Drake had been driven by a storm across the western mouth of the Straits, into an archipelago of islands on its southern side. Hitherto, it had been believed that Tierra del Fuego was attached to a huge continent spreading across the southern latitudes (‘Terra Australis’). Now, Francis Fletcher wrote, ‘We have by manifest Experience put it out of doubt to be no continent or maine Land but broken Ilands dissevered by many Passages & compassed about with the sea one every side.’ On board the Bonaventure, Ward had one of Drake’s charts. It made this clear, but Fenton and his officers doubted it could be true. Madox suggested he might even have made it up.[35]

Fenton now informed Madox that he hoped to do,

… som notabl thing, which I ges is ether to spoyl St Vinsent and ther to be king, or to pass to St Helens and attend the Portingal fleet fro Molucas, or to lurk abowt the West India til the kings treasur com fro Panamau.

In effect, the Straits and the Moluccas had been abandoned, although to his men Fenton remained non-committal, saying just that they should revictual before proceeding. The fleet sailed towards São Vicente amidst the murmurings of the crews – none more vocal than John Drake and the eighteen aboard the Francis. They slipped away the following night.[36]

A brief digression is warranted. The Francis reached the River Plate but was wrecked in its shallows. Captured by Charrúa natives, Drake and his crew were kept as slaves for fifteen months. Most died before John, Richard Fairweather and another escaped in a canoe. Later, they were taken into custody in Buenos Aires, where John was recognised as Sir Francis’s nephew. After interrogation, the three men were held in a hermitage in Asunción for more than a year. The others were given a measure of liberty – they married native wives – but Drake was kept in close confinement. He was permitted to speak to two people only, one a hermit, the other an Englishman who had been in the country for forty years and had forgotten his native tongue.

In the summer of 1586, Drake and Fairweather were summoned to Lima, where, from January 1587, they were subjected to the Inquisition. Drake, it is reported, was accorded the milder treatment: the more recalcitrant Fairweather recanted his faith on the rack. He was ‘condemned to reconciliation, four years of galleys and perpetual prison.’ Drake made a public confession and was confined to a convent for three years. He was then given the comparatively mild sentence of being restricted to Spanish territory for life, with the confiscation of all his property. The last mention of him is in October 1595, when he may have met Richard Hawkins, also a captive in Lima. Unlike Hawkins, however, Drake and Fairweather never returned home. Their knowledge of the South Seas told against them.[37]

Aboard the Bonaventure, Ward confesses his crew were doubtful about proceedings of the December council. He says they were mollified once he explained their intent. Yet, when the fleet reached São Vicente, on 20 January, the Portuguese prevaricated. Initially, Fenton hoped that an Englishman, John Whithall, might intercede to procure some trade. Having lived in Brazil for some years, he had married the daughter of a Santos sugar planter and was engaged in business with London. However, the population of the unprotected port were concerned by the warlike appearance of the English ships. Fenton may have issued threats: such at least was the claim of the Spanish in their later depositions. Certainly, the Portuguese knew that a Spanish fleet was in the area, and they had been told by Flores de Valdes neither to trade with the English, nor to give them succour. Finally, they decided that they were under an obligation to King Philip.[38]

By now Madox was sickening, and his diary ends. Henceforward, the record hangs on those who wrote to explain their conduct after the voyage ended. Some events are obscure.

The Battle at São Vicente (24-25 January 1583)

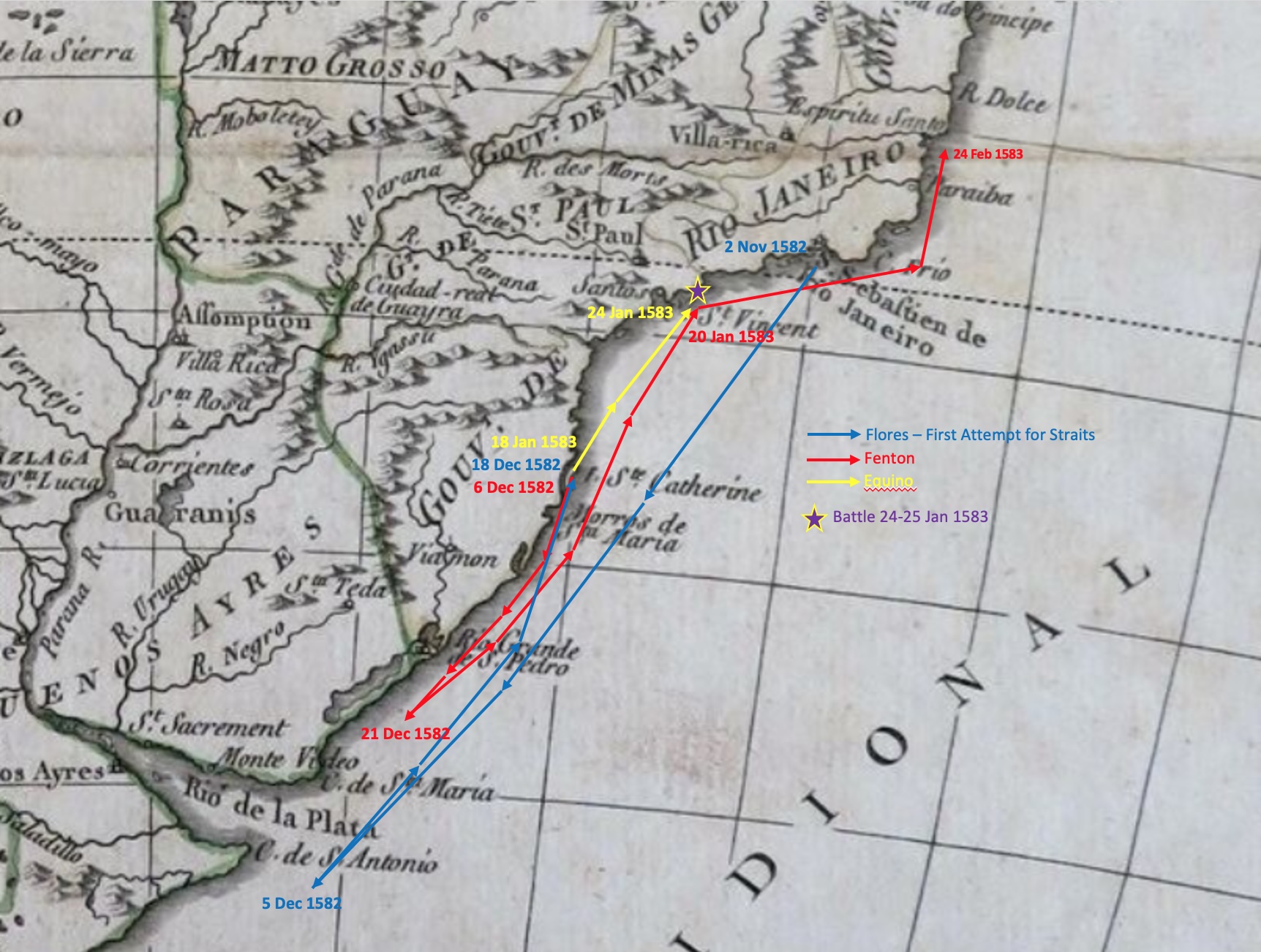

Valdes’ fleet had been sent by King Philip with a double purpose: to secure Portuguese Brazil, and to support the establishment of a new fort and settlement on the Straits, under Pedro Sarmiento. The fleet left Cadiz in December 1581, reaching Rio de Janeiro on 25 March 1582. From there, the Spanish sailed south, on 2 November. Even in the southern summer, however, they encountered severe storms. They reached a point just south of the River Plate, before they were forced back, for repairs. As they approached that river, on 15 December, they encountered the barque of friars which Fenton had seized at Isla Santa Catarina.

The friars told Flores that the English were equipped with two large ships ‘very well gunned and outfitted’, and that they had a very good appreciation of his fleet. They added that, three days before, Fenton had departed Santa Catarina for the Plate, where they believed he would remain ‘until such time as [Flores’] armada left the Strait, in order for them to go there and pass through into the Mar del Sur and to go to the Malucas.’

At this, Flores sailed for Santa Catarina. He knew that ‘the corsair’ had repaired his ships during his overstay there, and he thought that Fenton might have been forced back by the gales also. Between 18 December and 7 January 1583, nine of Flores’ ships were refitted for a second attempt for the Straits. It was decided that three others, San Juan Bauptista, La Concepcion and La Begoña, could not be repaired within the limit of forty days. They were put under the charge of Andres de Eguino, to be taken to Rio de Janeiro or São Vicente, to be refitted more slowly. Those settlers, their wives and children, and those men who were too sick to serve, were transferred to them, to relieve the rest of the burden. Don Equino departed Santa Catarina for São Vicente, on 18 January. On 24 January, he arrived there, even as the crews on the Leicester and the Bonaventure were making repairs to their topmasts.[39]

Fenton says that the Spaniards outnumbered his men 700 to 222; Lopez Vaz, a Spanish pilot, whose account was published by Hakluyt, that Equino’s ships ‘were weakened with former tempests, and were manned with the refuse of all the Spanish fleete.’ The strength of the Spanish vessels has since been a matter of some debate. The question arises, because, contra Vaz, Pedro Sarmiento wrote that ‘they were the best in the fleet.’ Sarmiento, however, was an implacable critic of Flores, who took every opportunity to blame him for the failure of the Straits settlement. The account of Pedro de Rada, the official scribe of the armada, steers a middle course. The ships, he agrees with Vaz, were carrying many deemed too weak for combat. On the other hand, Flores had ordered Equino ‘to attend to all the situations that were offered, because they had sufficient naos and men to attack and defend themselves from the corsair in case they met him or any others that were there.’ What Flores did not know was that Equino had since taken on board more people rescued from the San Estevan, which ran aground on 7 January, as well as sixty-four mutineers, who had been saved from the Sancta Marta, on 16 December. (They travelled overland to Santa Catarina, after being turned away by the Indians onshore.) It is also clear from Rada’s account that Equino departed Santa Catarina earlier than Flores might have expected. This could have been a mistake, though Rada says that, when Equino launched the attack, the three naos were ‘well in order’.[40]

According to Rada, battle commenced at around nine at night, when the Concepcion was towed alongside the nao capitana of the enemy and fired into her. As she responded in kind, the capitana lengthened her cable to pull away. Then Rada, in the Begoña, joined the fray:

And being fighting thus, the nao almiranta of the enemy arrived and, perpendicular to the stern of the nao Begoña, fired all its artillery. And by this assistance, they killed, on the said nao Begoña, Captain Jodar Alferez who had sailed on her, and with him another thirty men not counting others wounded. And there were so many pieces of artillery that the two enemy naos fired at the nao Begoña that they opened her up in many places; and without power to remedy the damage she went to the bottom in eight brazas …

According to Fenton, the Spanish took advantage of his ships’ unreadiness and attempted to tow away the Bonadventure ‘without answering me what they were when I hailed them … and so have entred his men aborde me’:

… there grew (unwillingie) on my part a sharpe conflicte betwixte him & me all that night, till such time as (god) gave me victorie against him by sinkinge him in the place, thedwarde as she might helpinge the same …

According to Ward, the first round of the battle ended at four o’clock in the morning. When the sun appeared, only the tops of the Begoña were visible above the waves. Some of her men had escaped to shore, but forty remained hanging in the yards. On Fenton’s orders, just two of these were taken off: one was later ‘heaved over boord, because he was soore hurt, not like to live.’ The remainder were left to fend for themselves, or to watch the next round of the engagement from the Begoña’s shrouds.

According to Fenton,

… the next daie the other ii fought with us till the afternone in a verie cruell sorte, but in the ende (god of his mercie) delivered us from theim without loss of above v men presentlie slaine & 30 sore hurte, the hurte of our tackle & other things and Losse of a cable and ancour, and one of thedwardes.

Regarding this struggle, Thomas Percy, master of the Bonaventure, complained that the English disengaged first despite their advantage, the Leicester a full hour before the Bonaventure, as ‘the men of the galeon were droncke wth a hogshead of wyne they had drancke, in the heat of the fight.’ There is some corroboration of this in the Spanish accounts. Lopez Vaz commented that the English might have sunk a second ship, had they not wished to avoid more killing. ‘Doubtlesse.’ he wrote, ‘it is the greatest valour that any man can shew, that when hee may doe hurte, he will not.’ Rada wrote that, after the battle, ‘the enemy capitana was very damaged and taking on water, because having left the port it was firing pieces towards its almiranta, which went ahead.’ He alludes to reports that ‘these corsairs left without having captured our naos, although they had great strength and could have achieved a better result.’

Ward was critical of Fenton to the point of crossing to the Leicester to remonstrate with him over his actions:

I called to our generall to wey, and drive downe to them, who required mee to goe first and anker on their quarter, and he would follow, and anker on their bowes. I weyed, and went downe, and ankered by them … There rid I alone, spending shot at them, and they both at me, foure hours, before our admirals anker would come up; during which time I had some spoile done; but when our admiral came, she had her part, and eased me very well.

At length our admiral began to warpe away, and being come without me, set saile, and began to stand out into the sea; I went aboord of him to know his pleasure. Who determined to get out of shot; but could not, because the winde scanted on them. The Edward before she could get up her ankers, endured many more shot, after the gallion was further of a good way then she, and sometime the gallion had two or three. Thus we ended about two of the clocke after noone …[41]

After this engagement, the Spanish retired into Santos, to repair: the San Juan Bauptista had been holed below the waterline several times. Fenton’s vessels sailed to the shelter of Burnt Island, a few leagues to the south. There, they took on supplies before, on 28 December, the Bonaventure departed in a strong breeze.

In the letter he composed to Leicester on his return to England, Ward claimed that the strength of the wind had caused his anchor cable to part and that, being obliged to stand out to sea, he had been unable to recover the Leicester. It was, he said, only ‘after many daies expectacon in vaine’ that, under the press of ‘being unprovided of many speciall nessysarys’, he sailed home.

Referring specifically to this voyage, Richard Hawkins, who, as William’s cousin, probably received a first-hand account of it, was apparently less than convinced. In his Observations of 1622, he warned,

… all men are to take care, that they goe not one foote backe, more then is of mere force; for I have not seene, that any who have yeelded thereunto, but presently they have returned home.

The intent of Fenton (as well as, later, of Cavendish), he wrote, had been to make another attempt on the Straits. Neither did:

… for presently as soone as they looked homeward, one, with a little blustering wind taketh occasion to loose company; another complaineth that he wanteth victuals; another, that his shippe is leake; another that his mastes, sayles, or cordinge fayleth him. So the willing never want probable reasons to further their pretences. [42]

The Bonaventure reached Plymouth on 29 May 1583, after a passage of three and a half months. On 5 February, John Walker, who had been sick with the flux, died. Ward wrote, ‘wee tooke a view of his things, and prised them, and heaved him over bord, and shot a peece for his knell.’ Later, on the isle of Fernando de Noronha, where Ward stopped to take on water and food, there was an encounter with Indians, in which five of his men were killed. He brought away a Frenchman who was in the Bonaventure’s skiff when the affray began. On 11 April, George Coxe, a ship’s carpenter, ‘having the night before broken up the hold, and stolne wine, and drunken himself drunke’ leaped overboard and was drowned. These things apart, the Atlantic crossing was uneventful.[43]

The Leicester did not reach the Downs until a full month after the Bonaventure. At first, Fenton persuaded himself that the battle at São Vincente had not destroyed the chance of trade with Brazil. He travelled to Espirito Santo where, on 27 February, Madox died. Negotiations began with the governor. They were interrupted only when a Portuguese barque from São Vincente arrived. Fearing duplicity, Fenton abandoned the attempt, and, on 5 March, he sailed.

On 1 April, he learned that there was no beef or beer remaining in the hold. Twenty barrels of peas were declared rotten. By 1 May, there were just five barrels of pork. By 1 June, none. Yet, amazingly, on 19 June, Fenton let slip his intentions, when he confided to his diary, ‘Altered my course from Newfoundlande.’ Perhaps he intended to prey on the shipping on the Grand Banks. If so, the death of seventeen of his crew in the succeeding three weeks showed the folly of his notion. He concedes the decision to return to England was greeted ‘by the consente of the whole Companie’, and when, eventually, the Leicester reached Cork, his diary reveals more than a hint of mutiny. He noted,

… hired Laborers aswell to fill my water as to keepe the Pompe goinge, which notwithstandinge, one Frye, and one Petre Robinson refused to do any worke, and Robinson beinge strook by me with my coogell offred force against me most disobedientlie & in Mutinous ordre wherby I was in perill of my life.[44]

William Hawkins was confined in irons and then placed in the bilboes. This ‘manifest wronge’ he called the whole crew to witness, whereupon:

… [the general] with vile speches towardes me sayed that if I spake one wourde more he wolde dashe me in the teethe, and called me a villeyn sclave, and arrant knave wyth many more vile wourdes …

On the voyage home, the dislike these two had for each other had reached such a pitch that, after one argument,

… the general wolde have drawen his longe knyfe and have stabbed Hawkins, and intercepted of that, he tooke up his longe staffe and thearwith was ronnyng at hawkins, but the master (Hall), Mr. Bannester, Mr. Cotton and Symin Farnando stayed his furye.[45]

Quite obviously, the voyage had been a disaster. Ambassador Mendoza says that Ward and Fenton were arrested on their return. However, if they were, they were not disgraced. Both served, five years later, in the Armada campaign, Fenton commanding the Mary Rose, Ward the Tramontana. (In 1590 and 1591, Ward served as ‘admiral’ in the Narrow Seas. He died shortly thereafter.) Against the Armada, William Hawkins probably captained the Griffin, and Ferdinando served under Frobisher in the Triumph. Nicholas ‘Pyrgopolynices’ Parker was knighted by Lord Willoughby in the Low Countries, in 1588, served in France, and in the Islands’ voyage under the Earl of Essex. He rose to become deputy lieutenant of Cornwall and governor of Pendennis Castle, before he died, in 1619.[46]

At his death in 1603, an epitaph to Fenton was raised in the Church of St. Nicholas, Deptford. It made but passing reference to the expedition of 1582-83, but otherwise it praised an illustrious career:

To the never-fading memory of Edward Fenton, formerly sentinel to the body of Queen Elizabeth, gallant commander during the troubles in Ireland, first against Shane O’Neal, and then against the Earl of Desmond, who, with extraordinary fortitude, explored the hidden seas of the northern quarter, and, in other voyages, revealed the hidden places of inanimate nature. As sea-captain, he merited the command of a royal ship in the celebrated sea-battle against the Spaniards, in the year 1588.

The Edward Bonaventure in European Waters (1584-1588)

Fortunately, Fenton’s failure did not lead to the abandonment of attempts to reach the Moluccas. Already, in November 1582, Ambassador Mendoza had reported that John Hawkins’s elder brother, ‘Older’ William, had been assembling a fleet of seven ships, two of them Drake’s, for the purpose. In fact, he met a reverse at Cape Verde before crossing to the Caribbean. There he had some success with the pearl fisheries at Margarita. Conceivably, he captured the flagship of Spain’s homeward-bound plate fleet (his loot was reported to be worth 800,000 crowns). Concrete evidence is lacking, but it is not impossible that he originally intended to pass through, or round, the Straits. In the Indies, he might have attempted to persuade, or coerce, Portugal’s colonies into deserting King Philip in favour of Dom Antonio, just as this might have been his intention at Cape Verde.[47]

Immediately after Fenton’s return, Mendoza warned King Philip that a ‘Moluccas venture’ was being prepared by the Queen’s ‘new favourite’, Sir Walter Raleigh. Then, in the summer of 1584, Sir Francis Drake proposed another voyage with himself as leader. A paper endorsed by Burghley, ‘The charge of the navy to the Moluccas’, refers to the monetary contributions of the Queen, Leicester, John Hawkins, the older William Hawkins, Drake, Raleigh, and Hatton.[48]

Neither expedition sailed. (Drake’s morphed into the 1585-1586 raid on the West Indies.) For a while, the press of events meant that the Bonaventure were confined to European waters.

Hakluyt refers to her, as one of a fleet of five tall, stout ships that were sent by the merchants of London, in November 1585, to Turkey, to frustrate a Spanish raid on the Levant. In July 1586, they fought a five-hour engagement off the island of Pantelleria, between Sicily and the African coast. They escaped through the Straits of Gibraltar in a fog, chased by a gaggle of galleys that ‘in a vain fury and foolish pride’, shot off their ordnance to no purpose and so ‘ministred to our men notable matter of pleasure and mirth, seeing men to fight with shadowes.’[49]

In the 1587 attack on Cadiz, the Bonaventure was one of seven ships assigned by the Levant Company to Drake’s command. As William Borough showed in his chart of the raid, she ran aground on the shoals of the inner harbour, as Drake led his attack on the town. However, she was recovered, and, against the Armada, she was appointed to Drake’s western squadron under the command of James Lancaster.

Lancaster, commander of the Susan in the Cadiz raid, was one of those to whom Drake had referred when writing to his Queen of the ‘especiall good service’ received from the merchants of London. Now, he and Robert Flick, commander of the Merchant Royal at Cadiz, were rated captains in the Royal Navy, ‘their experience and deserts deserving the same’, and a naval captain’s pay. During the Armada campaign, however, there are few clues as to the Bonaventure’s activities. The Merchant Royal is mentioned as one of five ships that, with Frobisher’s Triumph, were separated from the fleet and assaulted by a group of galleasses. They put up a strong resistance until relieved by ‘certain of her Majesty’s ships [that] bare with them.’ The Bonaventure is not listed as one of the five, but it is probable she was not far distant.[50]

The Troublesome Voyage of James Lancaster (1591-1594)

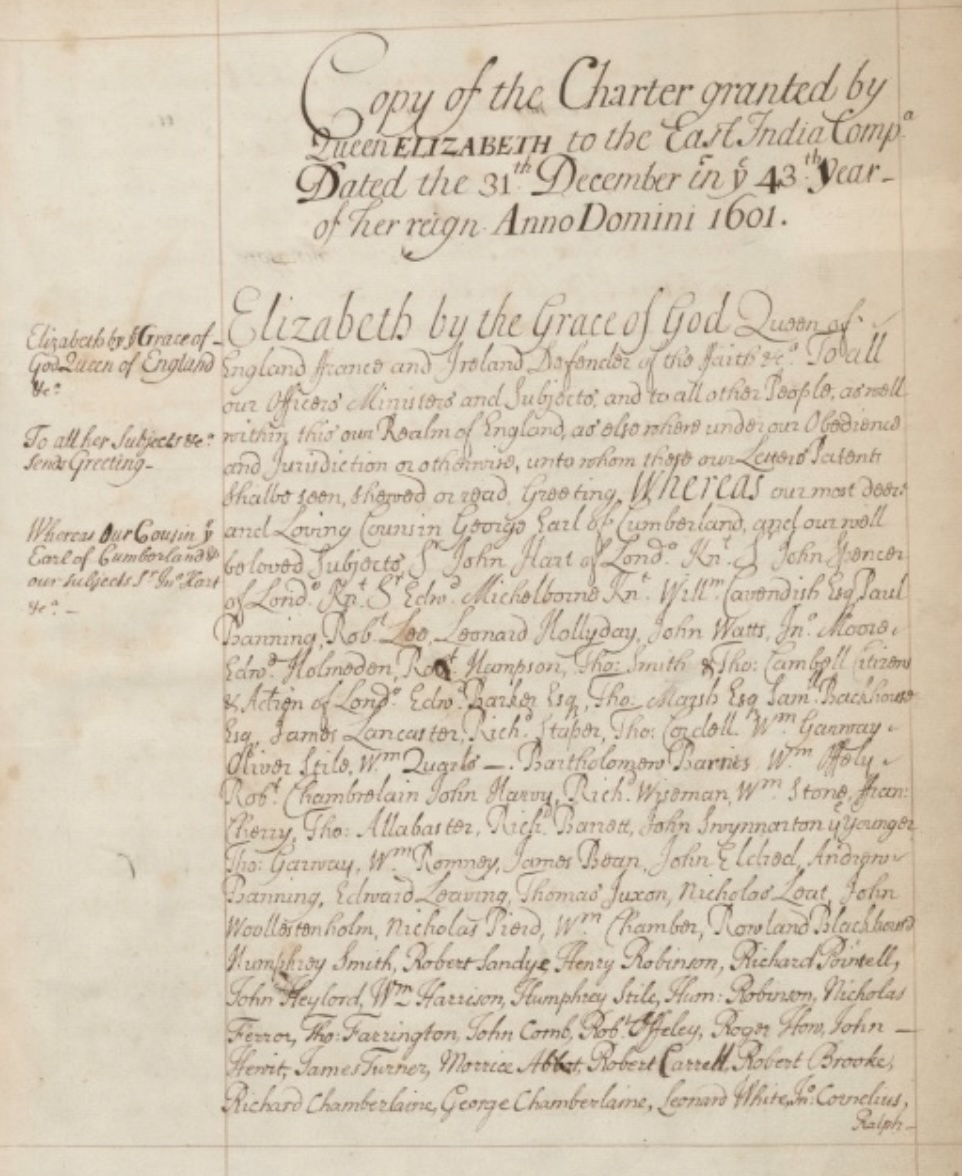

The Armada victory was a spur to confidence in British ships, something that Thomas Cavendish’s circumnavigation, in the 120-ton Desire, in 1586-1588, did nothing to dispel. In October 1589, a group of London merchants petitioned the Queen that they be permitted to sail to the Indies by way of the Cape.

Great benefitte [they said] will redound to our countree, as well for the anoyinge of the Spaniards and Portingalls (nowe our enemyes) as also for the ventinge of our comodities (which, since the beginning of thes late troubles, ys muche decayed), but especially our trade of clotheinge; of which kinde of comodities, and others which our countree dothe yeald, no doubte but a lardge and ample vente wil be founde in those partes.[51]

They proposed to send the Merchant Royal, the Susan, and the Edward Bonaventure but, before committing themselves, they sought an assurance that the ships, once ready, would not be held in abeyance for any reason, and that the promoters would be allowed to keep the booty for themselves. The answer to their petition has not survived, but they did not depart. Presumably they did not obtain the promises they sought. Possibly, the Queen was nervous of another Spanish attack.

Whether Lancaster was to have sailed with the Bonaventure is not certain. All we know of his activities is that, earlier in 1589, he commanded the 200-ton Solomon on the unsuccessful Drake-Norris expedition against Lisbon. This proved to be his last naval campaign, although the High Court of Admiralty records for 1590 show that he commanded the Bonaventure on a privateering venture that accompanied Sir John Hawkins’ expedition to the Azores. There, he was involved in a dispute over the capture of a small vessel, the Hope, which was Dutch, if commanded by a Spaniard.[52]

Then, in 1591, the merchants’ East Indies plan came to fruition. The vessels selected were, again, the Merchant Royal and the Edward Bonaventure, and the Penelope. George Raymond, owner of the Penelope, who had commanded the Elizabeth Bonaventure against the Armada, was placed in overall command. The Merchant was placed under the charge of Samuel Foxcroft. (He died early in the voyage.) James Lancaster commanded the Bonaventure.[53]

That he was familiar with Portugal is clear from his statement, contained in Hakluyt’s account of a later voyage that,

I have bene brought up among this people, I have lived among them as a gentleman, served with them as a souldier, and lived among them as a merchant, so that I should have some understanding of their demeanors and nature; and I know when they cannot prevaile with the sword by force, then they deale with their deceiveable tongues; for faith and trueth they have none, neither will use any, unlesse it be to their owne advantage.[54]

Possibly, the reference to service as a soldier is to Lancaster’s having sided with Dom Antonio at the time of King Philip’s annexation, in 1580. It is possible that, after Antonio’s defeat, he was forced to leave, and that he suffered financially. In any event, his knowledge of Portuguese and his proficiency in battle promised well for the voyage at hand.

We have two accounts of the expedition, one by Edward Barker, Lancaster’s lieutenant, another by Henry May, but little clue as to its instructions. As with Fenton, things went wrong from the first. The result, if not the intention, was that little attempt was made at trade. Mention is made of soldiers aboard and, since the first prize was taken off the western coast of Africa after just two months, the expedition might perhaps be regarded as a reconnaissance mission, to be funded – if possible – by the taking of booty.[55]

The fleet departed Plymouth on 10 April, which was too late. It became caught in the doldrums. The Portuguese caravel captured in early June yielded wine, oil, olives and other victuals judged ‘better than gold’, but the first two men died before the ships crossed the equator and, by the time the fleet reached the Cape, they were dropping like flies. It was decided to wait a month to permit them to recover.

The tribesmen, cloaked as they were in mantles of raw hide, appeared ‘very brutish’. They quickly disappeared. For two to three weeks, pickings were limited to a few cranes and geese, and mussels and other shellfish. Then the crews found a supply of penguins and seals on an island in the bay. Eventually, they ‘got’ a negro. He was given a few trifles and sent off into the country to find some cattle, of which he produced a good supply. For an ox, the price was two knives; for a bullock or a sheep, one, or less.

Yet the crews’ health was not fully restored. Judging that it was ‘good to proceed with two ships wel manned then with three evill manned’, it was decided to send fifty men back to England on the Merchant, and to continue with 198 aboard the Penelope and the Bonaventure. Those that quit the expedition had the easier time of it.

Having rounded the Cape, the fleet encountered what Barker called ‘a mighty storme and extreeme gusts of wind.’ May says they were ‘taken with an extreame tempest or huricano.’ He goes on to describe how the crew of the Bonaventure ‘saw a great sea breake over our admirall the Penelope, and their light strooke out: and after that we never saw them any more.’ Lancaster searched for the Penelope for a few days, and waited again for her at the Comoros, which had been fixed as a point of rendezvous. Four days into this uncomfortable separation, continues Barker,

… we had a terrible clap of thunder, which slew foure of our men outright, their necks being wrung in sonder without speaking any word, and of 94 men there was not one untouched; whereof some were striken blind, others were bruised in their legs & armes, and others in their brests, so that they voided blood two days after; others were drawen out at length, as though they had bene racked. But (God be thanked) they all recovered, saving onely the foure which were slaine outright. Also with the same thunder our maine maste was torne very grievously from the heade to the decke, and some of the spikes, that were ten inches into the timber, were melted with the extreme heate theereof.[56]

Proceeding alone, and only narrowly escaping the Bassas da India in the Madagascar Channel, the Bonaventure sailed to Canducia Bay, in Mozambique. Here Lancaster seized some native sailing barges (‘pangaias’), from which there were taken a Portuguese boy, and some maize, hens and ducks. The next destination was the island of Great Comoro. This was found to be ‘exceeding full of people which are Moores of tawnie colour and good stature, but … very trecherous, and diligently to be taken heed of.’ Treacherous indeed they proved. At the conclusion of negotiations over water with their king, the ship’s master, William Mace, and thirty-two of the crew were slain on the shore, the others, for want of a boat, being forced to watch the massacre from a distance.

With heavy hearts, the sixty or so remaining sailed to Zanzibar, where they captured a Moorish ‘Sherife’. Using him ‘very curteously’, Lancaster traded him with his king for two months’ worth of supplies. Here the Bonaventure halted between the end of November 1591 and the middle of February 1592, and here her surgeon died, as a result of ‘negligently catching a great heate in his head’ whilst negotiating the purchase of oxen on shore. Eventually, after taking advantage of the harbour, the watering and plentiful fish, and having repelled an attack by a Portuguese galley, the Englishmen prepared to leave. Before doing so, however, they used the opportunity of an approach by a Portuguese merchant, who sent his man to request some jars of wine and oil, to take ‘the Negro along with us because we understood he had bene in the East Indies and knew somewhat of the countrey.’

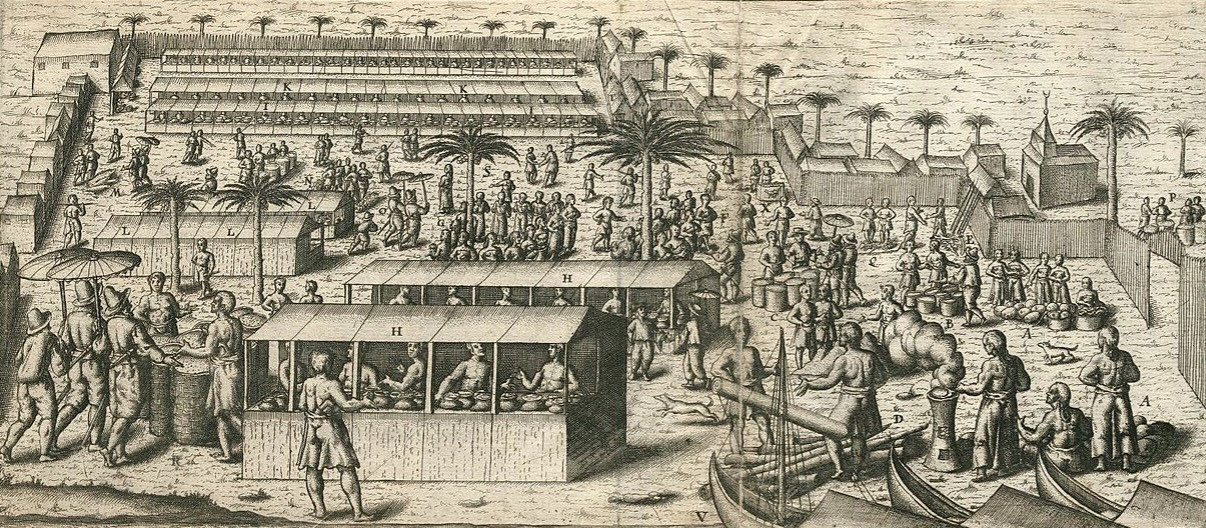

Lancaster now laid a course for Cape Comorin, on the southern tip of India. His purpose was to lie in wait for Portuguese ships passing between Goa and their settlements in Ceylon, Malacca, China, and Japan. These were known to be ‘of exceeding wealth and riches.’ But the winds and currents proved adverse, and they took the Englishmen far off their course. Indeed, so far to the north did they travel, that Lancaster determined to seek the Red Sea, or Socotra, ‘both to refresh our selves, and also for some purchase (booty).’ Both were missed as, in due course, was Comorin, which Barker put down to the obstinacy of the replacement master, John Hall. In May 1592, the Bonaventure rounded Ceylon and made for the Nicobars. This too was missed, however, ‘through our masters default for want of due observation of the South starre.’ It was early June before the Bonaventure halted at the Isle of Gomez, off the north-western point of Sumatra.

Lancaster hoped for a pilot, but none materialised. ‘Contagious’ weather was coming, so he set off again, still hoping for Portuguese shipping, and finally anchoring at Penang, ‘a very good harborough betweene three Ilands.’ By then, the men were ‘dying apace’. He decided to remain for the change in the monsoon, but the quality of the refreshing disappointed. There were just some oysters, ‘great wilks’ and a few fish. The sick were landed on the islands for their health, but twenty-six died, including the obstinate master and Rainold Golding, ‘a marchant of great honestie and much discretion.’ That left thirty-three and one boy, ‘of which not past 22 were sound for labour and helpe, and of them not past a third part sailors.’

At the beginning of September, the Bonaventure sailed for Malacca. Four vessels were taken, one of them laden with goods belonging to some Portuguese. She was stripped of her cargo of pepper, but the others, which were working for merchants of Pegu, in southern Burma, were released. Once the sick had been refreshed and made somewhat ‘lustie’ with these supplies, the Bonaventure set off again. Lancaster steered for the Sembilan Islands, to intercept more Portuguese. Before long, a 250-ton vessel from Negapatam, laden with rice, was seized. Then, on 6 October, another of seven hundred tons, from Goa. Barker writes,

At our comming aboord we found in her sixteene pieces of brasse, and three hundred buts of Canarie wine, and Nipar wine, which is made of the palme trees, and raisin wine, which is also very strong: as also all kind of Haberdasher wares, as hats, red caps knit of Spanish wooll, worsted stockings knit, shooes, velvets, taffataes, chamlets, and silkes, abundance of suckets, rice, Venice glasses, certaine papers full of false and counterfeit stones which an Italian bought from Venice to deceive the rude Indians withal …[57]

From this vessel, Lancaster took the goods he judged to be the choicest. The vessel itself he abandoned. Then, fearing the attentions of the Portuguese squadron at Malacca, he sailed for Ceylon, collecting pitch, ambergris and a quantity of abath (rhino horn) at Junkceylon (Phuket), and supplies at the Nicobars on the way. Lancaster’s plan was to halt at Point de Galle and there to ‘make up the voyage’, as May puts it, by awaiting ships from Bengal, or Pegu, or Tenasserim, which were expected to supply the Portuguese carracks that sailed from Cochin for Lisbon in mid-January. However, Barker explains,

Being shot up to the place aforesayd … wee came to an anker in foule ground and lost the same, and lay all that night a drift, because we had nowe but two ankers left us, which were unstocked and in hold. Whereupon our men tooke occasion to come home, our Captaine at that time lying very sicke more like to die than to live … Nowe, seeing they could not bee perswaded by any meanes possible, the captaine was constrained to give his consent to returne, leaving all hope of so great possibilities.[58]

On 8 December, therefore, they sailed for the Atlantic. A plague of cockroaches (‘flies’) meant that the store of bread was much depleted by the time the African coast was sighted, in February 1593. Then the Bonaventure was held up by contrary winds. It was mid-March before she rounded the Cape, and 3 April before she reached St. Helena. Here Lancaster halted to load with fresh fruit, goats, and game. And, to their surprise, his men discovered a crewman of the Merchant, who had earlier been left behind ‘to refresh him on the iland, being otherwise like to have perished on shipboard’:

Our company hearing one sing in the chapell, supposing it had bene some Portugall, thrust open the doore, and went in unto him: but the poore man seeing so many come in upon him on the sudden, and thinking them to be Portugals, was first in such a feare, not having seene any man in 14 months before, and afterwards knowing them to be Englishmen, and some of them of his acquaintance, in such joy, that betweene excessive sudden feare & joy, he became distracted of his wits to our great sorowes. [59]

This Robinson Crusoe figure was in fact John Segar, a tailor from Bury St. Edmunds. His companions clothed him in ‘two sutes of goats skinnes with the hairy side outwards’ and, in that guise, he crossed the Atlantic. He perished in the West Indies, ‘for lacke of sleepe’, according to Barker.

After laying in stores there, Lancaster next advocated sailing to Brazil. He had in mind Pernambuco (Recife), where the Portuguese had a vibrant colony harvesting brazilwood, used in the manufacture of dyes, as well as sugar and cotton. His men had other ideas. They threatened to ‘lay their hands to nothing’ if the Bonaventure did not steer for home. The consequence was that, for a second time, she was caught in the doldrums.

After six weeks, some of the men were ready to break into the chests of their fellows for food. The overthrow of the voyage threatened, but Lancaster, supported by one of those who had visited Trinidad on John Chudleigh’s circumnavigation attempt, persuaded his crew that it would be best to replenish supplies there. Unfortunately, the island was passed in the night of 8 June and, for eight days, the Bonaventure was embayed in the Gulf of Paria. After much struggle, she finally escaped it and reached the Isle of Mona, between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. There, at last, her men fell in with a French ship, captained by Charles de la Barbotière, secured some refreshing, and some fresh canvas, and stopped ‘a great leake’ which had broken upon their ship.[60]

No sooner was this done, however, than the mutinous members of the Bonaventure’s crew conspired to seize the Frenchman’s pinnace and, with it, to capture his ship and make away. The plot was revealed to de la Barbotière as he, Lancaster and Henry May were sitting down to dinner in the Frenchman’s cabin. May and Lancaster tried to ease his fears, but he was unpersuaded. He drew his ship apart, holding the Englishmen hostage ‘for his security’. In this sort, they had the discomfort of watching the Bonaventure weigh anchor for England. At the same time, two Moors and two Burmese, whom Lancaster had given to de la Barbotière, became separated in his ship’s boat and disappeared in another direction.

Fortunately for Lancaster and May, the boat and pinnace were recovered. So was the Bonaventure. A deal was struck whereby Lancaster exchanged the Spaniards and the negroes aboard her for the boat. Friendship was restored, ‘to all our joyes’, and it was agreed that May should return with de la Barbotière ‘to certifie the owners what had passed in all the voyage, as also of the unrulinesse of the company.’

This done, it was decided that, Fenton-like, the Bonaventure’s next destination should be Newfoundland. A storm drove her along the southern coast of Hispaniola, but she escaped destruction once more, cleared the passage between Haiti and Cuba, and then sailed around Cape Florida and the Bahamas, into the Atlantic. Then, on 17 September, she was engulfed, almost literally, by another storm which carried away the sails and left six feet of water in the hold. Lancaster and his men had just pumped this out when the labouring of the ship caused the foremast to give way, and the ship to refill as before.

The wind died to nothing. Fresh water and victuals fell into short supply. For a week, there was nothing but hides to chew on. Finally, a stop was made on an island near Puerto Rico where the Englishmen found land crabs, water, and turtle. They refreshed themselves over seventeen or eighteen days and made ready to depart. Then Lancaster was told, flatly, that five of the crew were going no further. They stayed behind and were collected afterwards by another English ship. Just twenty-four men and a boy remained.

By 20 November 1593, the Bonaventure was back at her anchorage at the Isle of Mona. Lancaster, with eighteen of the crew, landed to find food which, once again, had fallen critically low. They collected what provisions they could over two to three days, but the wind got up and, with it, the swell. The men remaining on board were unable to use the diminutive ship’s boat to retrieve them. When the Bonaventure’s carpenter decided the effort was useless, he cut the ship’s cable. For a second time, she drifted away.

For the men left behind there was barely sufficient food. They split into groups to forage independently. Lancaster and his companions survived on the stalks of purslane and such pumpkins as grew in a nearby garden. Then, after twenty-nine days, they attracted the attention of a passing French ship. They were taken off the island and divided between this and another French vessel that arrived on the scene. They then sailed for the north side of Santo Domingo, where they remained until April 1594, trafficking in hides with the natives. Barker continues,

In this meane while there came a shippe of New-haven (Le Havre) to the place where we were, whereby we had intelligence of our seven men which wee left behinde us at the isle of Mona: which was, that two of them brake their neckes with ventring to take foules upon the cliffs, other three were slaine by the Spaniards, which came from Saint Domingo, upon knowledge given by our men which went away in the Edward, the other two this man of New-haven had with him in his shippe, which escaped the Spaniards bloodie hands.[61]

Eventually, on 7 April, Lancaster and Barker left for England aboard another French ship captained by John Noyer of Dieppe. They reached France, on 19 May 1594, and landed at Rye five days later. They had been away comfortably more than three years, ‘which the Portugales perform in halfe the time, chiefely because wee lost our fit time and season to set foorth in the beginning of our voyage.’

There remain just a few loose ends to tie up.

The first is the fate of Henry May, who sailed separately with de la Barbotière for Europe. From Mona, they crossed to Hispaniola, where they remained until the end of November. Then, nearly three weeks into their trans-Atlantic passage, on 17 December, de la Barbotière’s pilots, assuring their captain they were clear of all danger,

… demanded of him their wine of heigth: the which they had. And being, as it should seeme, after they had their wine, carelesse of their charge which they tooke in hand, being as it were drunken, through their negligence a number of good men were cast away.[62]

The ship had struck the rocks on Bermuda.

Being the only Englishman aboard, May watched the survivors (about half the crew) clamber into the ship’s boat and onto a raft. At first, he feared that, out of concern for their self-preservation, they would cast him overboard rather than have him join them. Quaking, he remained upon the filling wreck until called over by de la Barbotière. Reunited, the survivors rowed for the whole of the following day, until they reached a wooded island with just a little water:

Now [May writes] it pleased God before our ship did split, that we saved our carpenters tooles, or els I thinke we had bene there to this day: and having recovered the aforesaid tooles, we went roundly about the cutting downe of trees, & in the end built a small barke of some 18 tun, for the most part with tronnels (wooden pins) and very few nailes. As for tackling we made a voyage aboord the ship before she split, and cut downe her shrowds, and so we tackled our barke and rigged her. In stead of pitch, we made lime and mixed it with the oile of tortoises; and assoone as the carpenters had calked, I and another, with ech of us a small sticke in our hands, did plaister the morter into the seames, and being in April, when it was warm and faire weather, we could no sooner lay it on but it was dry and as hard as stone.

… and at our departure we were constrained to make two great chests, and calked them, and stowed them on ech side of our maine mast, and so put in our provision of raine-water, and 13 live tortoises for our food, for our voyage which we intended to Newfoundland.[63]

They left Bermuda, on 11 May 1594, and reached Cape Breton Island, on 20 May. There, they were supplied with food and furs. Shortly afterwards, May separated from the others and joined a ship for Falmouth, which he reached in August.

He has the distinction of being the first of his countrymen to have landed in the Bermudas. He spoke highly of its store of ‘fowle, fish and tortoises’, but was less taken by its hogs. They were ‘so leane that you cannot eat them, by reason the Island is so barren.’ However, there were compensations. To the east, there was a large, landlocked harbour, where vessels of two hundred tons could ride in safety and, although the islands were subject to foul weather, the supply of pearls was as good as any in the West Indies.