Compared to his predecessors, Best was a new type of commander. Whereas James Lancaster, the Middletons and William Keeling had been merchants with some understanding of seafaring, he was first and foremost a ship’s captain and navigator. The younger brother of George Best, commander of the Anne Francis in Frobisher’s third voyage to Baffin Island, by 1612 he had been going to sea for a little less than thirty years, serving on voyages to Barbary, Russia, and the Levant. In appointing him, the Company were possibly responding to the way Phillip Grove, master of the Ascension, had steered her onto the shoals off Surat, in September 1609. Probably, they were thinking of the reception the Dragon would receive from the Portuguese, and of the skills her commander would require in the event of hostilities.[4]

The master of the Dragon was Robert Bonner, the son of a merchant captain during the Armada campaign. In 1615, he served again when Keeling took Sir Thomas Roe to India. He died as the Dragon’s commander, when she was lost to the Dutch in an unequal engagement off Tiku, in October 1619. The master of the Hosiander, for most of the voyage, was Nathaniel Salmon. Representing the merchants of the Company were Thomas Aldworth, Paul Canning and Thomas Kerridge. [5]

Aldworth, an early supporter of Richard Hakluyt, was a sheriff of Bristol who had fallen on hard times: at his death, we know he had debts still outstanding to the king. It was upon this ‘Trustie and loving Subject’ that Best’s powers were to devolve should he suffer any accident during the voyage. Events were to prove Aldworth deserving of the Company’s trust.

Canning, second to Aldworth, also came from Bristol, but he was more prosperous, and this may have affected their relationship. Just as there were disputes between Canning and Aldworth, so there were others between Canning and Salmon. ‘Discord and dissension’ between Canning and Richard Petty caused the latter to be replaced as master of the Hosiander during the outward voyage. In short, Canning impresses as one not lacking in self-confidence, who was unafraid to criticise. Yet he was not short of courage and, for one, Ralph Standish, the Hosiander’s surgeon, considered him worthy of support.

Kerridge was another West Country man, from Exeter. He was a sympathiser of Aldworth’s, and so he tended to be critical of Canning, whom he considered ‘full of controversy’, ‘envious’, ‘conceited’, and bibulous. Kerridge was head of the Surat factory from 1615 to 1621, and from 1625 to 1628. He was elected a ‘committee’, or director, of the Company after his return to England, a post he retained until his death at the end of 1657, or in early 1658. Writing in 1934, Sir William Foster considered him one of the outstanding figures of the early English connection with India. In 1618, Sir Thomas Roe had some reservations. As he prepared to leave India, he declared himself happy to be leaving behind a domineering and envious personality, although he conceded that ‘[Canning’s] paynes is very great and his Partes not ordinarie.’[6]

The ‘Warre’ of Thomas Best

The Dragon and Hosiander were accompanied on the outward voyage by the Solomon and the James, which were sailing for Bantam. The master of the James was John Davis of Limehouse. He had served on Lancaster’s First Voyage, on Edward Michelborne’s interloping expedition of 1604-1606, and as David Middleton’s pilot on both the Consent (1607-1609) and the Expedition (1609-1611). His assistance goes some way to explain why the voyage to the Cape was more straightforward than most.[7]

It began inauspiciously, on 16 February 1612, when Best ordered that a three-gun salute be offered to some merchant well-wishers. Unfortunately,

… the gonner gave fire to a seycker (saker) which, being overcharged, brok in peecces and killd one man right out, laymed another, which afterwards dyed, and hurtt another.

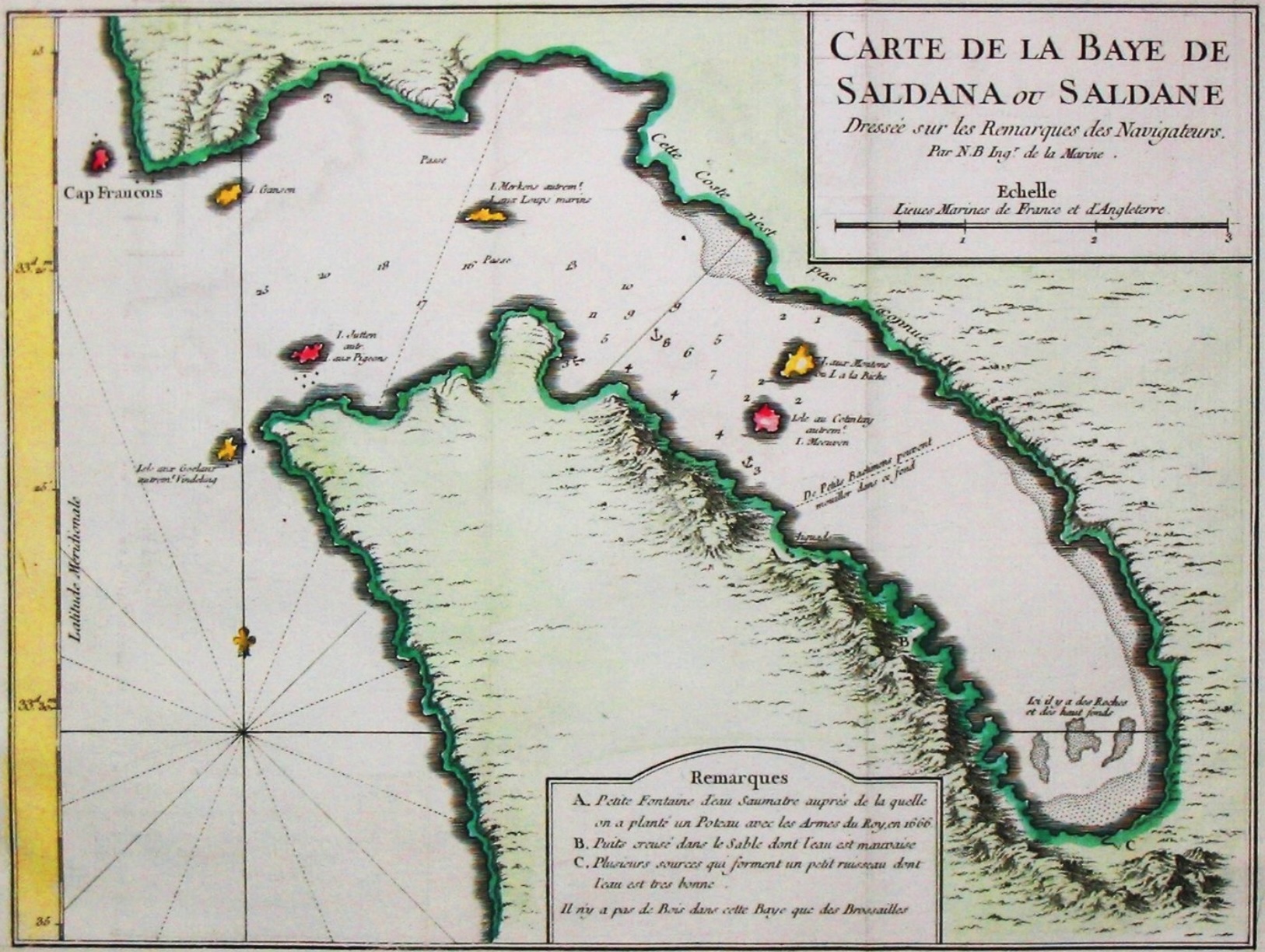

Thereafter, it was smooth sailing. After a quick stop in the Cape Verde Islands, the turning point of Trinidad was reached at the end of April, and Table Bay in early June. Best’s journal, it might to be said, is business-like to the point of being prosaic. At the Cape, he mentions the discord between Canning and Petty but, of the stop itself, he says little other than that ‘it is a place of greate refreshing.’ Happily, others left accounts which are more colourful.

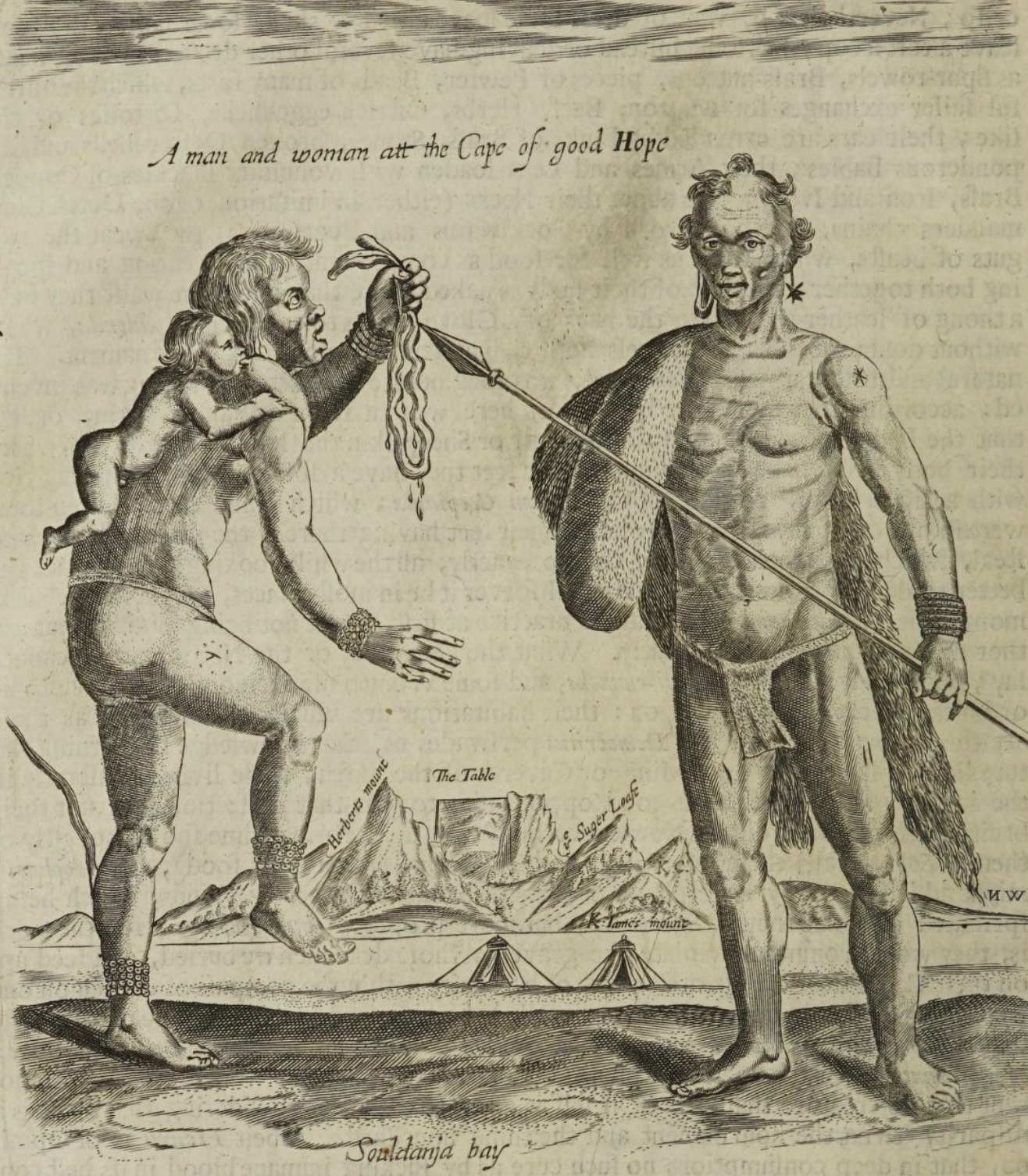

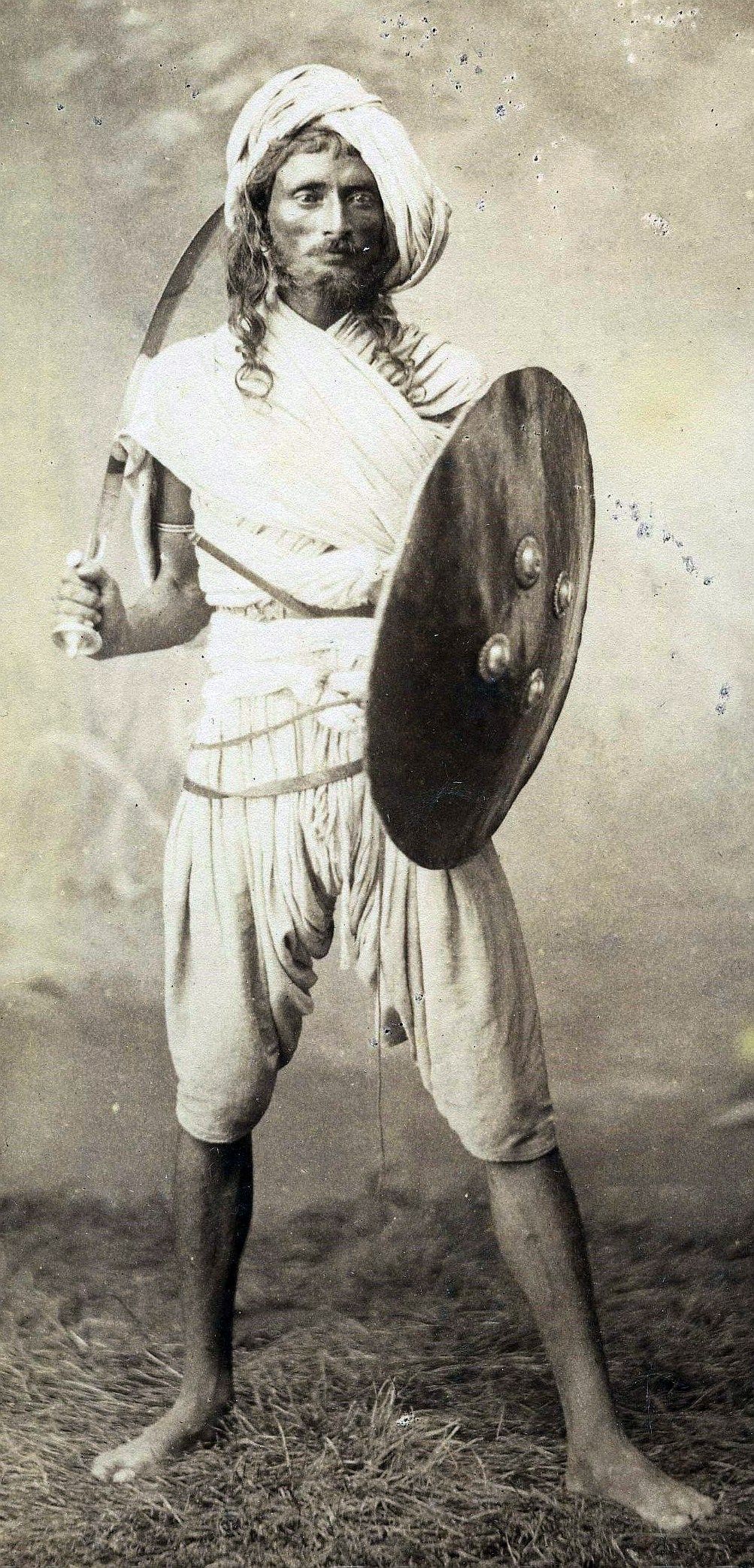

Ralph Standish explained that, in one respect, the passing of five years had made the Saldanians more discerning. In 1607, Keeling had paid for victuals with iron hoops: now they demanded brass. A piece a foot across purchased an ox, which in England would have cost £6. A piece the size of a finger secured a sheep ‘greatt of bone butt verie thin of flesh, shaped like a gre[y]hound, save onelie the eares longe.’ In other respects, Standish was more effusive in his criticisms than Lancaster or Keeling before him. The natives, he exclaimed, were,

… bruitt and savadg, withoutt religion, without languag, without lawes or goverment, without manners or humanitie, and last of all without apparell, for they go naked, save onlie a ppeece of sheepes skyn to cover ther members, that [in] my opinion yt is greatt pittie that such creattures as they bee should enjoy so sweett a connttrey.

He mentioned a visit to a nearby island where there were to be found seals and ‘fowlles called penquins, from whence the illand hath yts name.’ Like some birds he had previously encountered in Trinidad, these were as big as ravens but, since they could not fly, the men could take them up in their hands and, in quick order, load a ship. Unfortunately, like Trinidad’s birds, the smell of fish made them so ‘rance’, the crews could not bring themselves to eat them. Even so, the country deserved its epithet ‘sweett’. Upon their arrival, the Dragon’s men were scarcely able to bring her into harbour. After just a few days of ‘sheepes’, ‘beifs’, fresh salads, fresh air, and fresh water, they recovered their health and became strong.

Patrick Copland, chaplain on the voyage, was more lavish in his praise. The Cape, he wrote, ‘is so healthfull and fruitfull as might grow a Paradise of the world.’ However, although he found the Saldanians ‘loving’ and he approved of the measures of their dance, and of their respect for his sermon, he was forced to agree that their eating habits were reprehensible. ‘Their neckes,’ he avowed, ‘were adorned with greasie tripes, which sometimes they would pull off and eat raw.’ He concedes the women ‘were shamefac’t at first,’ but he was undoubtedly shocked when ‘at our returne homewards they would lift up their rat-skinnes and shew their privities.’[8]

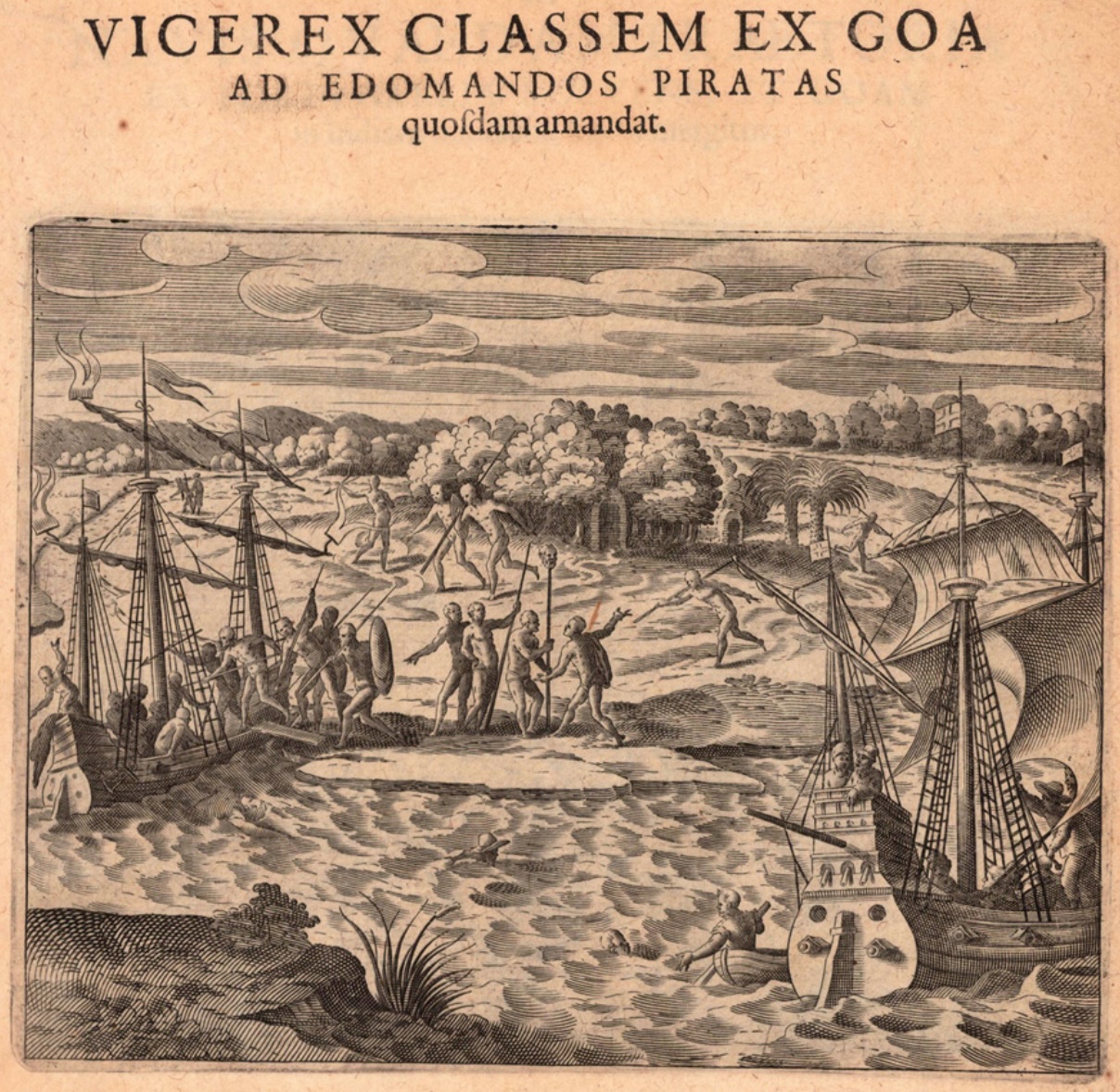

None of this features in Best’s account. Yet, even allowing for the concision of his log, it is noteworthy how little he makes of his first encounter with the Portuguese. This was in the Mozambique channel, on 30 July 1612:

This day in the morning we sawe two greate shippes, which in the afternoone came faire by us and saluted us with a peece; which we requited with the like, but spoke not with them.

It takes Standish to flesh out the details:

Being by estimacion of[f] the illand of St. Lawrance (Madagascar) … we meett with towe carroccks of 15 or 16 hunderd tonne of burden; which we did think was comed from Lisburne. The vice-admerall bore upp with us, and we, feareing the wurst, shott att hir, and she att us, butt wether in jeast or earnest, we cannott tell. Butt we shott att hir in all aboutt 17 greatt shott, and we had from hir aboutt 12; but she never strok us nor harmed us, allthough I do think they did ther best endevour to have strok us.[9]

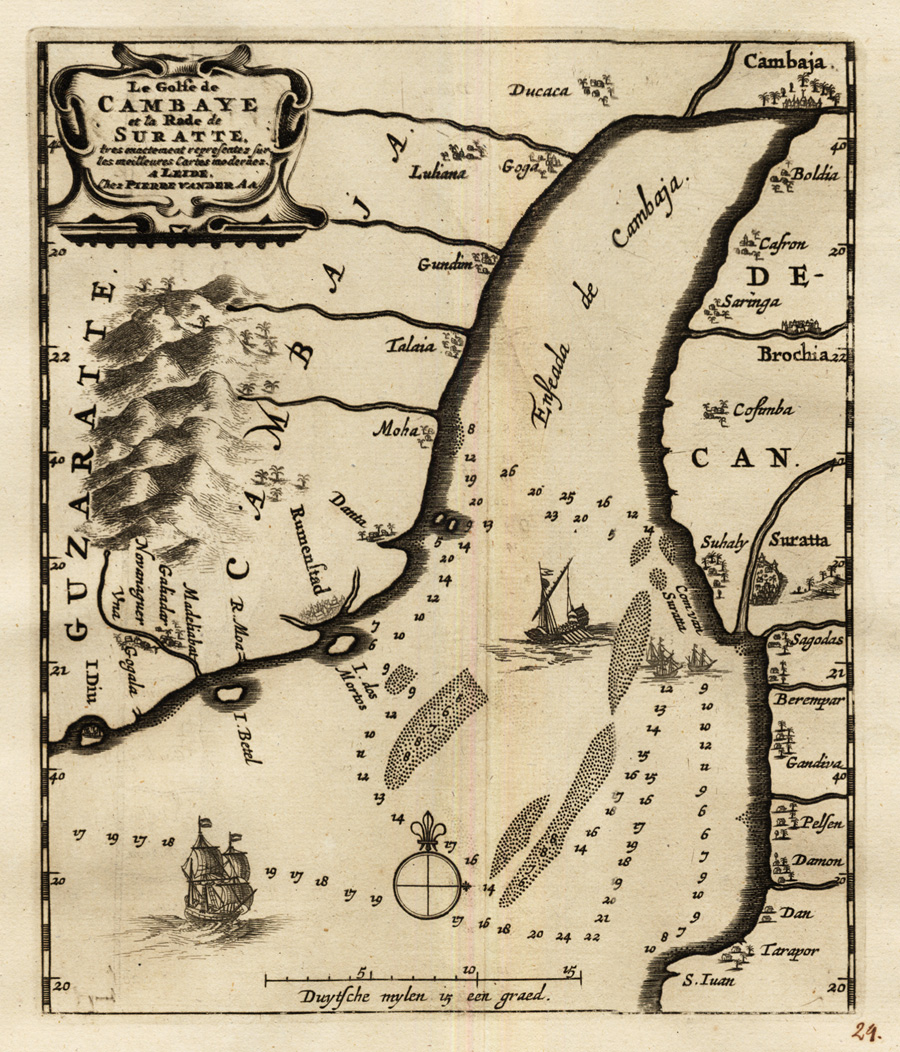

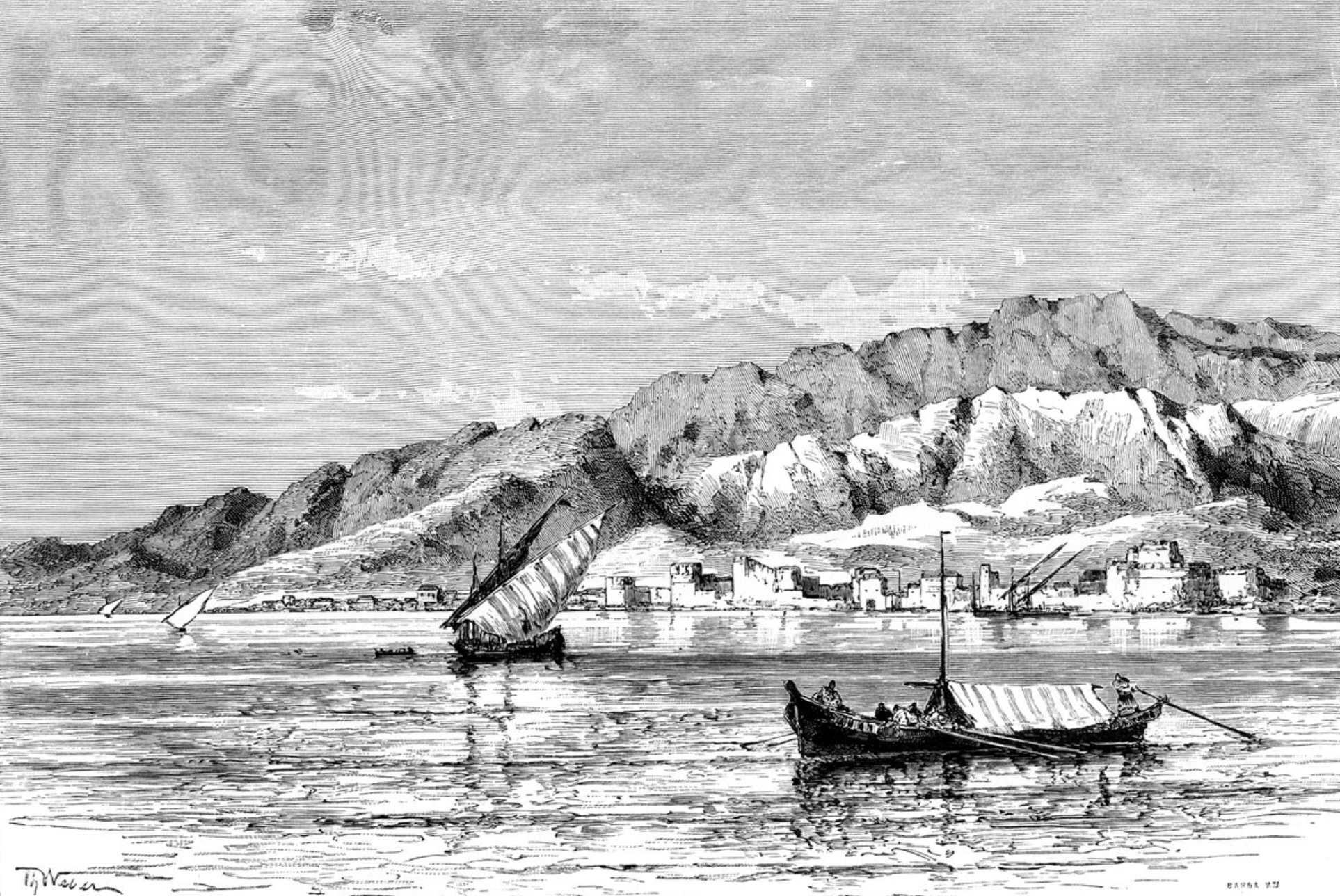

Standish later learned that three Portuguese had been killed. The Dragon, he says, was willing to fight it out, but ‘she needed nott, save onelie a saluttinge peece or tow.’ Best steered his course away, as it went against the terms of his commission to meddle with those with whom the English were at peace. (They would get plenty of practice later.) Thereafter, with a brief stop at the Comoros, the Dragon and Hosiander sailed eastwards. On 30 August, the sight of snakes swimming at the ship’s side told Best he was close to land. On 1 September, they reached the Indian coast at Daman, a hundred miles to the north of Bombay.

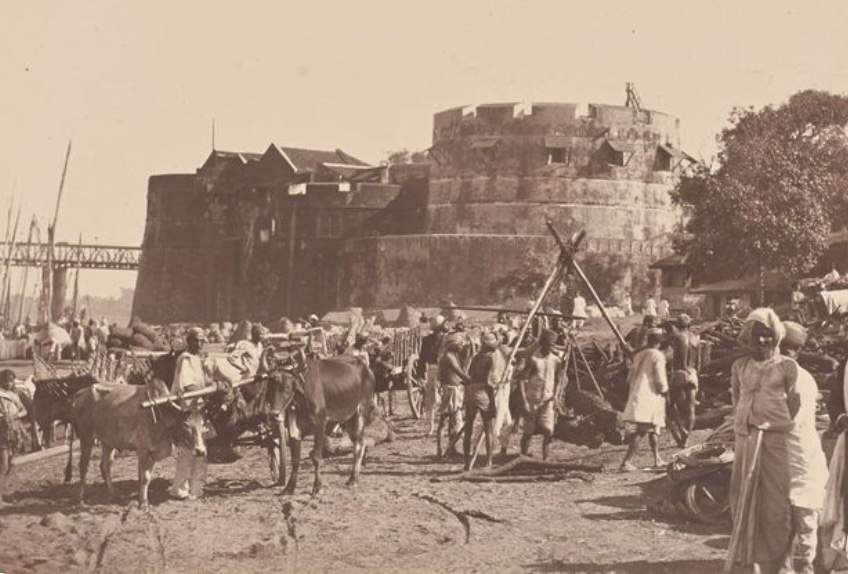

Robert Bonner was sent ahead to Surat to find a pilot and to obtain news on the state of the factory. He took with him Thomas Aldworth, Thomas Kerridge and fifteen other men, for protection. Unexpectedly, within two days, they discovered the Dragon was following on their tail. At the cost of ‘a 3d. knife’ per man, Best had found pilots of his own. This was unfortunate as, in accepting theirs, the Hosiander had offered their carpenter, William Finch, as a pawn for his safekeeping. Finch’s reward for letting slip he was carrying some money was to have his throat cut.

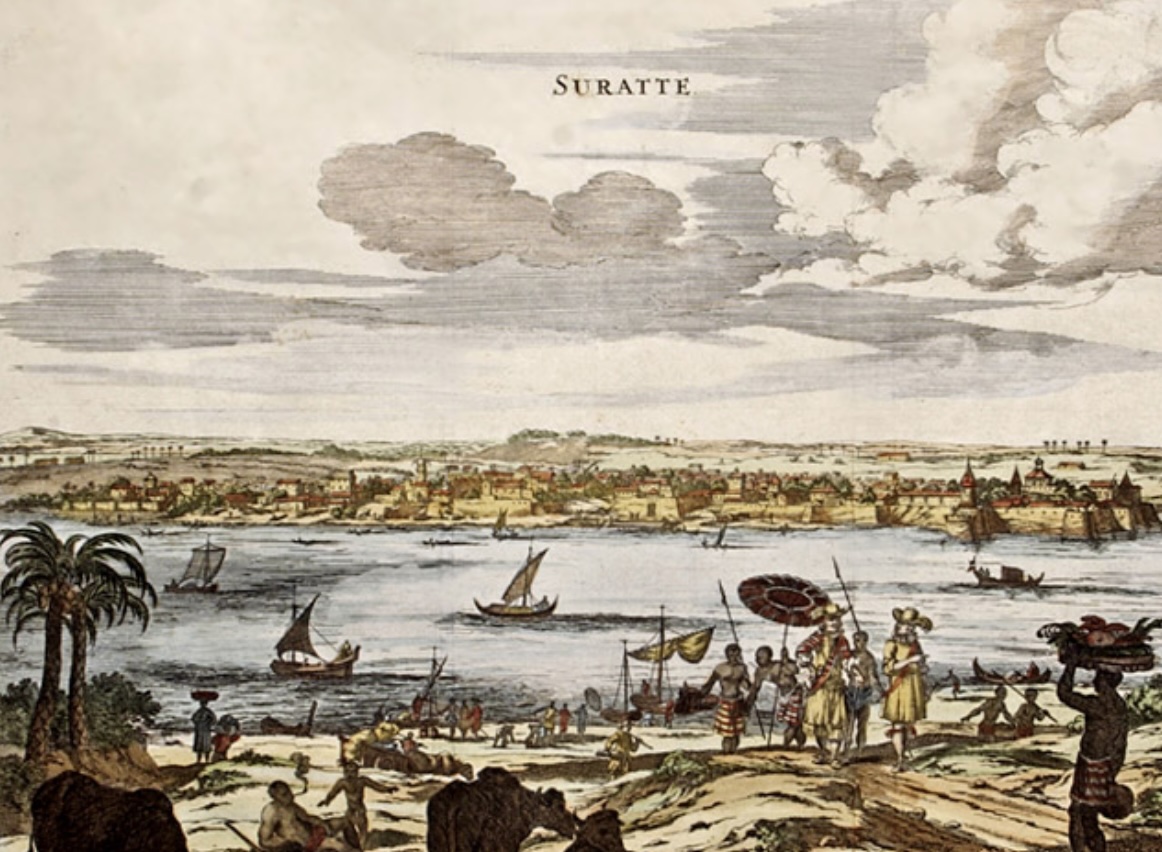

At Surat, the Englishmen were greeted by a native broker, Jadu, and several worthy citizens, including the brother of Mukarrab Khan, Hawkins’ and Middleton’s nemesis. Jadu brought a letter left by Middleton. It warned that no trade was to be expected, that the people were not to be trusted, and that Hawkins and the other merchants given up and gone home. To Salmon, the tidings were ‘as warme to his stomack as a cup of coole water in a frosty morning,’ but the Indians were more optimistic and, for now, Best concentrated on them. When the merchants returned to town, they took Thomas Kerridge and a few others with them.

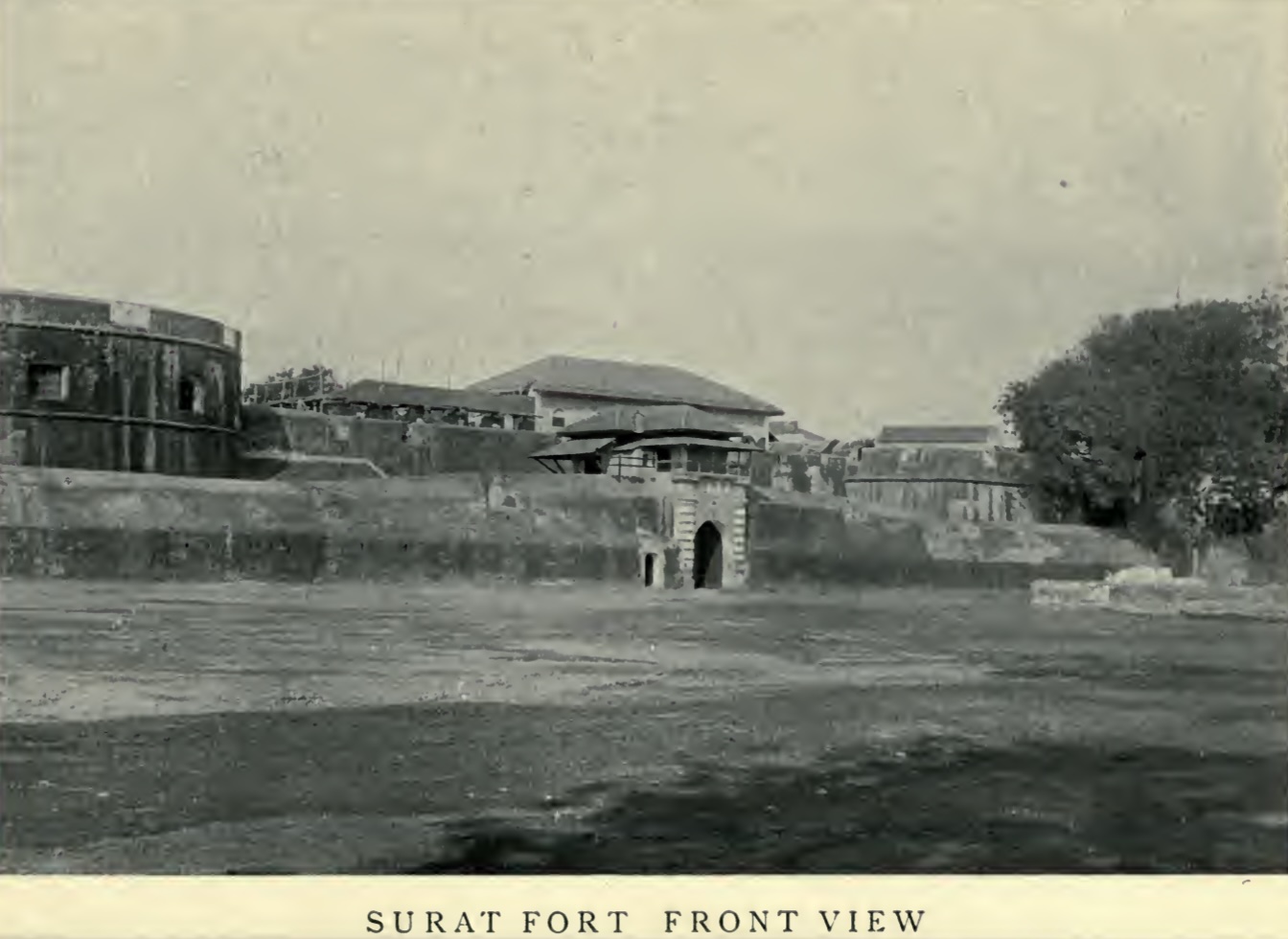

Before long, Kerridge was back aboard the Dragon bearing a certificate from the governor which proposed a quiet and peaceful trade. The positive effect was slightly blunted when a ship’s boat was caught in the current and seized by a ‘Mallabar frigott’, but a display of cannon-power meant she was recovered at little cost (‘save our men a little pilliged and the losse of a musket’) and relations were quickly restored. On 13 September, the governor of Surat fort and some other ‘gallantts’ brought aboard provisions. These were returned with gifts including a piece of silver, a gun, a sword blade, some knives, and a few rials of eight. When the deputation departed, Aldworth, Canning, and some others accompanied them, to negotiate terms. At this stage, despite the menace posed by the native boats, which were periodically fired upon, expectations ran high that Middleton’s pessimism was unfounded. News of his reprisals in the Red Sea had not yet reached Gujarat, and his earlier threats of retribution, if trade was not granted, may have kept the natives ‘honest’. It will have helped that Mukarrab Khan and the Portuguese were absent. On 22 September, Best’s council responded to a request from Aldworth and Canning, and landed a substantial quantity of cargo. A message was sent to Agra, to inform the emperor of the fleet’s arrival, and to obtain guidance on whether they were to be permitted a factory and a trade.

These plans were almost immediately compromised. On 24 September, a Gujarati ship arrived from Mocha with letters from Henry Middleton. They included a safe pass for the ship’s master, to ‘signifie [his] honestie … and to intreate all the Kings subjects not to molest nor trouble him.’ It was a first hint of what Middleton had been up to. Sure enough, reports quickly followed that several Gujarati vessels had been seized. At first, Aldworth feared for his own safety and for the Company’s goods: there was, he wrote, ‘a generrall murmoringe in the citty aboute this newes.’ The reaction of the Indian merchants, however, was less severe than he expected:

… wee founde the people very reasonable [Aldworth wrote], and the cheefes came unto our howse, desiringe that this newes mighte noe way dismay us, and notwithstandinge this injury donne to them by Sir Henry, wee should finde all honest respect from them unto us; and withal requested us to write home in their beehalfes for restitution of their losse that way sustained; which wee promised them to doe.[10]

By now, however, the return of the Portuguese had complicated the situation. A few days before, one of their boats had evaded the English guns and entered the shallows, where it was beyond reach. Standish grumbled that ‘with drawen swords florishing upon the poup or sterne, nott careing for us 2 pins, [they] stoad to the barr in a bravado.’ On 29 September, some others came within range, were fired upon, yet rowed away unharmed towards the river mouth. This profoundly irritated Best, who vociferously criticised the Hosiander’s gunner for ‘makeing so many bad shott att the frigotts without doing them any harme.’ He summoned Paul Canning and Edward Christian (his ship’s purser) back to the Dragon, but they were captured by the Portuguese before they crossed the bar, and sent as prisoners to Goa.

Best responded by seizing one of two Gujarati vessels in the harbour. He informed the Surat authorities that she would be released only after the men and goods which he had sent ashore were returned. The Surat merchants sent a deputation bearing gifts, which were reciprocated, but they failed to make guarantees. In his turn, Best refused to make concessions. He took the Dragon, the Hosiander and the captive vessel to the Swally Hole, where he knew he could better protect them.

On 12 October, Best paraded his martial strength in ‘a gallant shew’ to the people on land. He took eighty men, split them into two groups and, for the onlookers’ benefit, staged a ‘skrimidg or tow.’ His message was clear. For all that the Portuguese had just got the better of them, the English deserved respect. Amidst the show, however, one senses bluster, possibly even consideration of an alternative plan. In one of his letters, the purser of the Hosiander, Ralph Croft, wrote,

The General was much troubled about having sent his goods and merchants on shore, wishing them all in safety again, that he might better carry away that Portuguese ship.

Apparently, Best believed a Gujarati ship operating under a Portuguese pass was a legitimate target. Certainly, as he detected a tension in strategic thinking between the voyage’s officers, Croft’s sympathies lay with the chief merchant on shore. Aldworth, he wrote, ‘endeavoured by all means in his power, both with our General and also with the Governor of the place, to establish commerce with them, although our General was of a contrary opinion.’ Aldworth shared Croft’s doubts about Best. Later, on 25 January 1613, he wrote a private letter to Sir Thomas Smythe, in London, in which he was directly critical:

We experienced some difficulty in setting up the factory here [he explained]; and principally because the General was so incredulous. He could not be persuaded that we should have here a peaceful commerce, even when the King’s farman arrived; and this has been a cause of much loss to us. Furthermore, he has departed with not even half the merchandise he might have taken. He is a man of good understanding, but too much inclined to his own will. However, I hope that from henceforth our affairs will go with a smoother current.[11]

These criticisms struck home. When Best returned to London, in 1615, the Directors taxed him with the suggestion that Aldworth’s resolution alone had kept him true to his commission; that, if he had followed his own instincts, ‘the future hopes of ever setlinge any trade there [would] have bene quite taken away.’ Best’s response was that he had landed his goods despite Middleton’s contrary advice, which showed his instincts were true, and that when the news of Sir Henry’s seizures first reached Surat, Aldworth had written to him ‘a timerous letter, as one that expected none other but death.’ His limited resources had given him few levers with which to respond to a threatening situation. He believed his seizure of the ship had secured the factors’ safety at a time when, because of their ‘simplicitye and weaknes’ and ‘wannt of good securitie’, there were good reasons to fear for it.[12]

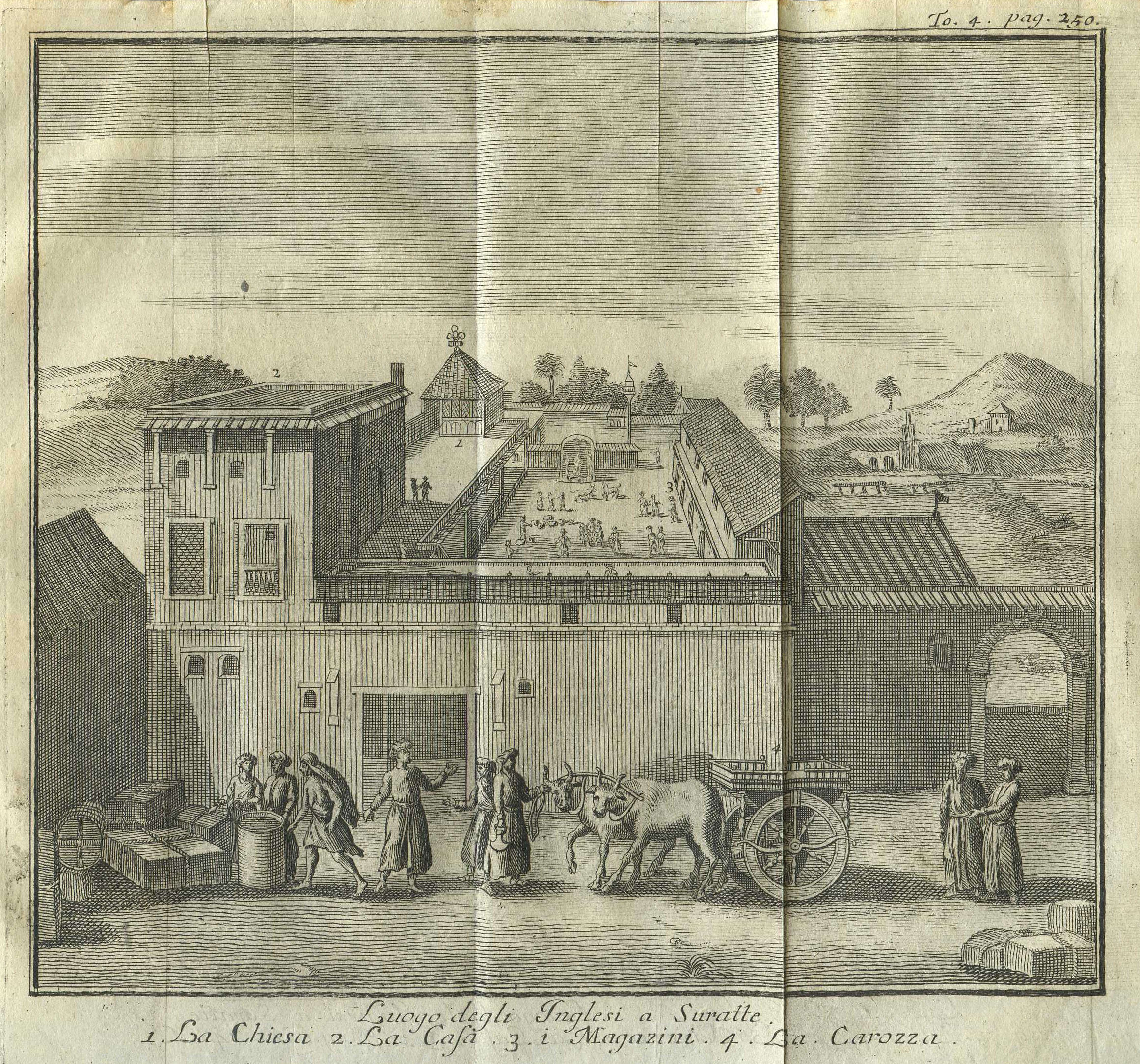

It is not clear that the Directors were entirely convinced by Best’s arguments. (The picture is muddied somewhat by their doubts over his private trade.) What is evident is that when, in 1612, Best summoned Aldworth aboard the Dragon, Aldworth refused to return. His refusal does not suggest excessive timorousness. Best was obliged to set up his stall, literally, by pitching two tents on the beach, one for himself and his attendants, and another for his escort, ‘for that the wether was verie hot.’ He waited on developments.[13]

On 17 October, the Governor of Ahmedabad arrived at Swally, claiming the authority of the Great Mughal. Together with the Governor of Surat, he invited Best for discussions. Best played hard to get. He insisted that four hostages be put aboard the Dragon to guarantee the Indians’ good behaviour. Then, on 19 October, the negotiations began. In short order, an agreement was reached for the settling of factories throughout the Mughal’s dominions. There was to be no compensation for Middleton’s earlier seizures, and customs were to be paid at the standard rate of 3½ per cent. The English and their goods were to be protected against the Portuguese on land, they were to be permitted an ambassador at the Mughal’s court and, within forty days, the emperor’s representative would deliver formal confirmation of the agreement’s terms, under royal seal. The prize ship was handed over.[14]

Best showed the governor King James’ letter and present but – ever the stickler – he then withheld them, saying they would be surrendered only against receipt of the emperor’s final agreement. If Jahangir refused to seal it, he declared, ‘then he was not a freinde but an enemy, and to the enemyes of my King I neither had letter nor present.’ While he waited, he wrote to Sir Thomas Smythe, passing on the governors’ suggestions for gifts. A knife, worth £8 or £10, he said, was more esteemed than two or three pieces of broadcloth or plate, and five or six cases of ‘hott waters’ (spirits) would be most apposite. So too would ‘a good store of pictures, espetially such as discover Venus and Cupids actes.’[15]

On 21 October, the two sides celebrated the agreement with some music. An Indian played upon a ‘strang instrewmentt’, an Englishman upon the virginals (a kind of harpsichord). The recital was so well-received that Best presented to the emperor, not just the instrument, but also its player. The player was Lancelot Canning, cousin of Paul. A cornet player, Robert Trully, travelled to Agra with him. Unfortunately, whilst the cornet appealed, the virginals did not. ‘A bagpipe had been fitter for him,’ declared Kerridge, and, according to Trully, Lancelot quickly ‘dyed with conceiptt.’ Jahangir was sufficiently taken by the cornet that he ordered his workmen to make six more. (The experiment failed.) Trully was asked to train a court musician, which was scarcely more successful because, although the musician mastered the craft in five weeks, he died of the flux two weeks later. Trully was destined to be the only cornet player in the kingdom, and a fretful one, at that. Repeatedly he was called to the royal presence but,

… sometimes returned without playing, staying till midnight and not called for, and as soon as he was gone, called for, whereat the king was once exceeding angry yet never gave him anything only 50 rupees which he took so indignantly that he would scarcely play before him …

According to Nicholas Withington, he ended his days playing in one of the Deccan courts, for which privilege he was circumcised and given a new name.[16]

That, however, is to look some way into the future. For now, to those at Swally, things were set fair. Best went riding in the countryside. He permitted Captain Hermon and his soldiers to build an encampment on shore. True, the discipline of the English was a little ragged: one of the Dragon’s men was confined in the bilboes for counterfeiting Best’s hand on a payment to the Indian merchants, and the Hosiander’s boatswain was ducked from the yardarm for swimming ashore, on the sabbath, ‘and drinkinge drunk with houres (whores).’ Nevertheless, relations with the Governor of Ahmedabad were sufficiently friendly that, during a visit he made to the Dragon, Best was persuaded by him to put one of the crew, whom he intended to hang for theft, at liberty.

Then, on 7 November, there came reports that a fleet of four galleons and twenty-five other sail was being assembled by the Portuguese, to make slaves of the English. The news was confirmed three weeks later, in letters sent from Goa by Canning and Christian. Captain Hermon was told to pack his tents. Standish reports that Best,

… comaunded [the Hosiander’s] master to come off with his shipe and ride by him in the offen, to maike readie our feights (screens against boarding), and to beatt downe all our cabins and fitt the shipe for feight, for that the Porttingall had vowed to taik us, and receved the sacramentt upon ytt, [and] had promissed cloth to many of ther frendes, as iff we had bene allreadie taken.

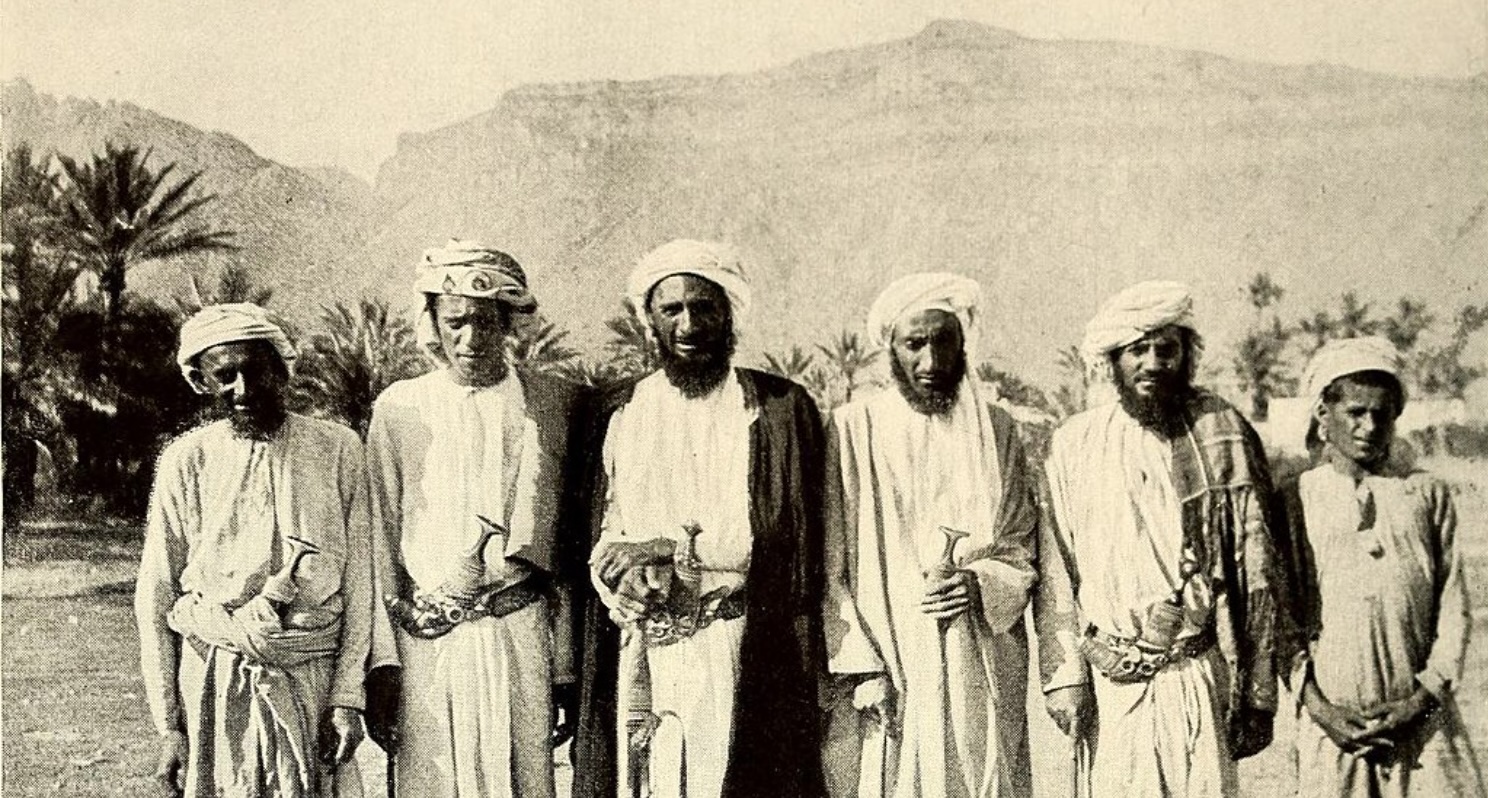

On 28 November, the Portuguese arrived. Their first act was to deliver Canning to the Surat factory. Contemptuously, they declared that they expected soon to have him prisoner again. For all that, when Aldworth and most of the merchants stayed put in town, Canning insisted on taking his chance on the Hosiander. First, he crossed to the Dragon, to tell Best of the forces ranged against him. The Portuguese, he said, had between 150 and two hundred men in each of their ships, and fifty to sixty in each of their boats: in total, a force of about two thousand, or ten times that of the English. Their flagship had thirty-six cannon, the other frigates about twenty each. Given their overwhelming advantage, the Portuguese commander, Nuno da Cunha, fully expected the English to yield, ‘in hope of favour’. What these numbers do not reveal is that most of the Portuguese were soldiers, equipped for hand-to-hand combat. Unless they could board the English ships, they offered more hindrance than help. Writing after the event, the Portuguese chronicler, Antonio Bocarro, explained that their vessels had fewer sailors, fewer cannon, fewer gunners. Their ships were larger than the Dragon and Hosiander, but they were slower and less manoeuvrable. Mostly, they were manned with Malay lascars who, ‘as they go to sea merely for gain, do their best to avoid fighting, because it does not profit them.’[17]

Correctly, Best realised that his ships stood little chance if they fought within the confines of the Swally Hole. He determined that the battle should be fought on open water. Before fighting commenced, he crossed to the Hosiander, to check her preparedness and fighting trim. King Harry-like, he addressed her crew, saying:

Allthough [the Portuguese] forcces weere more then oures, yett they were both basse and cowardlie, and that ther was a sayinge nott so common as trew: Who so cowardlie as a Porttinggall? and that after the first bravado was past, they were verie cowards, as he in former tymes had found them by experience. [He] did therffore perswad everie man to be of good courage, and shew oursellves trew Englishmen, famoussed over all the world for trew vallour; and that God, in Whom we trusted, would bee our helpe.

Having given similar encouragement to the men of the Dragon, Best took his ships to battle.

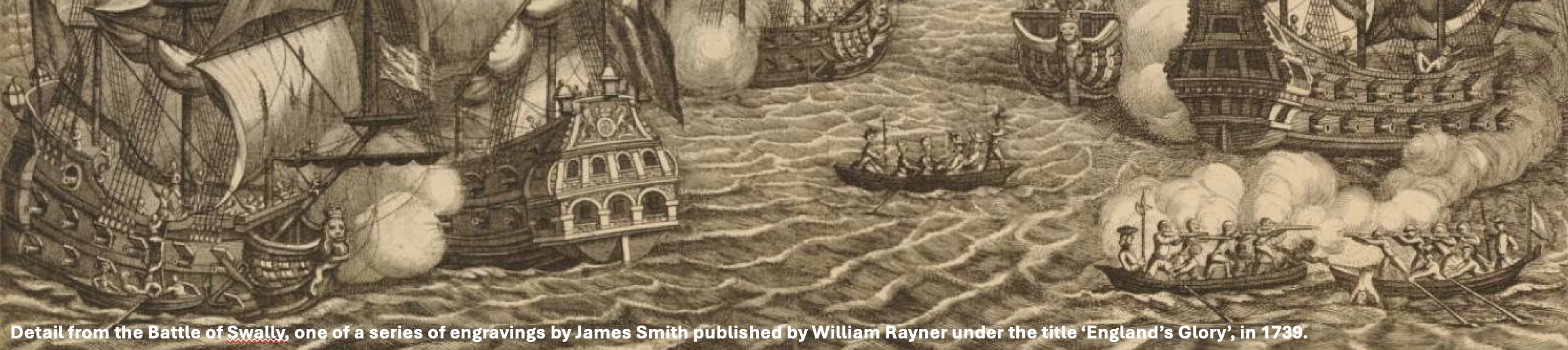

In the first round, an uneven contest, the Hosiander was mostly the spectator of events. In an exchange lasting an hour, Best reports that the Dragon peppered the enemy’s flagship with fifty-six great shot, as well as with small. In return, she received ‘one smale shott (sacker or ‘minion’) into [her] main mast.’ Another ‘sunke’ her long boat.

From the Hosiander, Ralph Standish enjoyed an uninterrupted view:

We had the wynd of them, which we aymed to keep. [We] stood right with them, with flags, ancientts, and our pendantts att everie yardarme. Ther vice-admerall was the headmost shipp. The Dragon steered direcctttlie with hir and, haveing hailled hir with a noisse of trumpetts, gave hir a salluttinge peece under hir sterne. She answered hir agayne. Then the Dragon came up with hir and gave hir a holle broadsid for a wellcome; which we did see to raik hir thorow and thorow. We heerd ther people make a greatt crie, for that yt could nott otherwisse bee butt that they had recceved greatt spoille and harme from the Dragon. She shott att the Dragon, but shott over and did hir no harme, save onelie the sinkeinge of hir longboatt; which that night they freed and maid theitt (tight) agayne. The Dragon did so plague the vicce-admerall that the admarrall and the rest rune away before the wynd.

On 30 November, when the conflict was renewed, the Hosiander was more involved. The English sailed out at dawn, on a falling tide. Guns blazing, Best steered his ships between the enemy before coming to anchor at nine o’clock. By then, three Portuguese frigates were grounded on the bar. As usual, Standish’s account is the more colourful. The Dragon was in the vanguard, he wrote, and being ahead, gave Nuno da Cunha ‘such a breakfast as [he] litle expecctted’:

[The Hosiander was] nott farr from hir, to second hir in the best manner we could. We sent them tokens to lett them tast of our curttesey. We came so neere that we never shott butt prevailled, being amongst them, where they all did shott att us … For the spacce of 3 or 4 houres our feight endured. We stood of intto the chennell for deeper watter, [and] ankered in 7 fadom watter, aboutt a league from the enemie. They spoilled us some tacklinge, butt no more harme as yett.

The Portuguese ships refloated with the flood. Combat was renewed and lasted all afternoon. During this phase of the battle, the Dragon fired some 150 great shot. She disengaged at nightfall, firing cannon from her stern at the Portuguese flagship, and receiving one shot in exchange which, Best says, ‘came even with the top of our forecastle, shott through our david (anchor davit) killed one man, to witt Burrell, and shott the arme of[f] another.’

On the Hosiander, Standish wrote,

Att afternone, with [the] flod we weid. And the Dragon weid likewisse, and wentt upp with thre of them; where she plaid hir partt couragiouslie all this afternone. One beinge from the rest a good distance and (as we did think) was aground, we came upp close upon hir steerbord sid, within ½ a stons cast and lesse of hir. With this shipp we spentt all this afternone in feight. We made 100 greatt shott this day – langrill, round, and crossebar – besides our small shott … Our boattson had one of his armes taiken away, with other towe mortall wounds, one in his bodie, the other in the other arme. I did my best endevour to give him cumportt; butt being broken clene in sunder (the wound in his body more daungerous) ther was butt small hop of his life.

In all, just two were killed, and one wounded. Damage was slight. That evening, a Portuguese vessel was sent ‘to do some mischief’ against the English – perhaps by cutting her cable, perhaps as a fireship – but she was sunk with a few well-directed shots. As Standish puts it, ‘they maid a pitt for us and fell intto yt themselves.’

Antonio Bocarro’s remarks on this engagement are revealing. On the first day, he says, the English took advantage of the swiftness of their vessels and their preponderance of artillery, and the Portuguese killed were thirty or so. On the second day, the artillery combat was renewed and,

… as the galleon of Gaspar de Mello was putting its bowsprit on the stern of the enemy pinnace, in order to board her, the galleon went aground, and the pinnace saved herself over the shoals or sandbanks that are in the sea around the Pool of Surat. The same misfortune happened to Manuel de Andrade Beringel, when he endeavoured to overtake and board the English ship.

Bocarro argues that the credit due to the English would have been greater if they had made it a point of honour ‘never to show their backs’:

… for, being ships of war, we should feel it a great disgrace to avoid an encounter; while they, relying only on artillery fire from a distance, withdrew or came on as they pleased, being enabled to do so by the handiness of their vessels, which were well-fitted and better sailers than ours.

Certainly, the English had the advantage that their ships drew less water and so could retreat and advance when it suited them. Yet, the implication is that Portuguese tactics needed reform, an impression that grows when Bocarro argues that,

… the resolution of the Portuguese … exceeds everything, and they are so eager and desirous to try any way with these enemies except artillery fire that they even board sailing ships with oared boats …[18]

Standish says that, after breaking off, Best was ‘bold to have banged yt outt’ with the Portuguese, if they had they followed, or if the ‘chief’ in his ship, presumably Bonner, had not discouraged it. Instead, he took his ships into deeper water, where there was less risk of grounding, and of being boarded. For two weeks, the English rested at Kathiawar, on the western side of the Bay of Cambay, taking in supplies and investigating its harbouring potential. In the council, however, there was unease. The merchants, led by Canning, were resolute for battle, but Best prevaricated, and doubts grew over his intentions. Standish heard that he had been half-persuaded by Bonner to leave the Portuguese and put to sea, ‘to see if we could take any Ormus men bound for Goa.’ On 16 December, the tensions came to a head. Canning urged Best to return to Surat,

… and, findinge the Generall so sudenlie allttered from his purposse, seamed much discontented. For that tow or thre daies before, he had called both shippes companyes together and tould them he meantt absolutlie to go over to Sualley Roode and dispatch bussines from Suratt, and if that the Portingailles should come, then to feight yt outt and wynn the trad by force of armes … Butt betwixt spirittuall and temporall tymeservers, the Generall was cleare of another mynd, to the greatt grieff and discontent of some of our chieffest wellwishers of the vaige.[19]

Apparently, one of those minded otherwise was Patrick Copland, the Dragon’s chaplain. One wonders what Aldworth and the men in Surat would have made of the idea that they might be abandoned. Fortunately, the arrival of the Portuguese, on 22 December, forced Best’s hand. Upon their approach, a friendly Mughal general, who was besieging pirates near Mahuwa, warned Canning that he did not rate his chances. In reply, Canning swore that God was on the side of the English, and would prove it in the action, despite the disparity in forces. Khwaja Yadgar was impressed, and offered to supply powder, shot and victuals. The next day, he watched in admiration as the English sailed in their two ships to confront their enemy.

Standish reports that, during this engagement,

The Dragon, being ahead, steered from one to another, and gave them such banges as maid ther verie sides crack; for we neyther of us never shott butt were so neere we could nott misse … And the truth is we did so teare them thatt some of them weere glad to cutt cables and be gone. This morneinges feight was in the sight of all the army, who stood so thick upon the hills, beholdinge of us, that, the number of them being so many, they covered the ground. We lost no tyme nor spared neyther powther nor shott, as our specctators ashoare can well wittnesse how this day we paid them, and maid them rune away …

Thus encouraged, the English attacked again the next day, the Dragon (in Standish’s words) giving the Portuguese admiral the first Bon Jour, the Hosiander the Besa los Manos and the Portuguese admiral, being ‘unwilling to complement any longer with us’, doing the ander per atras. The Portuguese flagship was set on fire, and Bocarro confirms that the flames were only with difficulty extinguished.[20]

This battle did no end of good for English prestige. According to Nicholas Withington, who stayed in India after Best’s departure, the witnesses ashore spread the news far and wide. Khwaja Yadgar gave Jahangir a detailed account, ‘which made the Kinge admire much, formerlye thinking there had bin noe nation comparable to the Portungale by sea.’

At the end of the encounter, everyone agreed that the expenditure of ammunition had been such that, for the time being, the Portuguese should be left to their devices. Best returned to Swally. He arrived to find that, still, the emperor’s firman had not arrived. It was expected, but Best was suspicious. He needed time to resupply but, with the passage of the days, he grew impatient. The risk that the Portuguese would return may have concerned him but, arguably, he was more anxious to follow Middleton’s lead, and fill his ships with cargoes pillaged from Gujarati vessels. On 5 January 1613, he instructed the merchants at Surat to abandon the town and return to their ships. Again, Aldworth refused. He insisted that he had to remain, if there was to be any chance of trade being secured. This stayed Best’s departure for a few days. On 11 January, the firman appeared. In Aldworth, it seems, the Company had much to be thankful for.[21]

The firman itself is lost, so we do not know its terms. Later, in 1615, the emperor denied that the specifics had been approved by him and, since the governors who negotiated the terms had died, he sanctioned a general firman only. However, at the handover ceremony with Best, the Indian officials swore that the Persian document replicated the terms of the earlier agreement, and promised,

… great curtteses and privilidges for trad all ther counttres over, nott onelie at Suratt butt all the counttrey over, as Amedvar (Ahmedabad), Cambaia, or any other part of the countrey that would afford us any comodities to our content.[22]

Accordingly, after the sounding of trumpets and the firing of a volley, or two, Best agreed that Thomas Aldworth, Thomas Kerridge and William Biddulph should remain at Surat with Nicholas Withington, and that Paul Canning should lead a deputation to Agra, to deliver King James’s letter and present. Best’s steward, Anthony Starkey, was sent overland, via Sind and Persia, to deliver the good news to London. Copland later reported that he was poisoned by friars on the way, but he certainly reached Aleppo before January 1614. The letters themselves never reached their destination. They were passed to the Portuguese, who sent them to Madrid, which issued an instruction to Goa to be more vigorous against the English.[23]

By now, the Portuguese were hovering offshore. A plan for sending the Hosiander to England with a cargo of goods was abandoned. Best accelerated his preparations. He exchanged lead and iron for eight bales of calicoes, and, on 17 January, he departed under cover of night, promising to return from Bantam in the autumn to collect the goods sourced by the factory for England. The morning found him almost within shot of the Portuguese, but Best refrained from meddling with them and, although the Portuguese briefly gave chase, they quickly desisted. ‘Thus,’ says Standish,

… we partted from thes valient champians, that had vowed to do so such famous acctts, butt yet [were] content [to] give us over, with greatt shame and infamy redounding unto themselves. Butt this was the Lords doinges, and God graunt us grace to give Him the glorie.

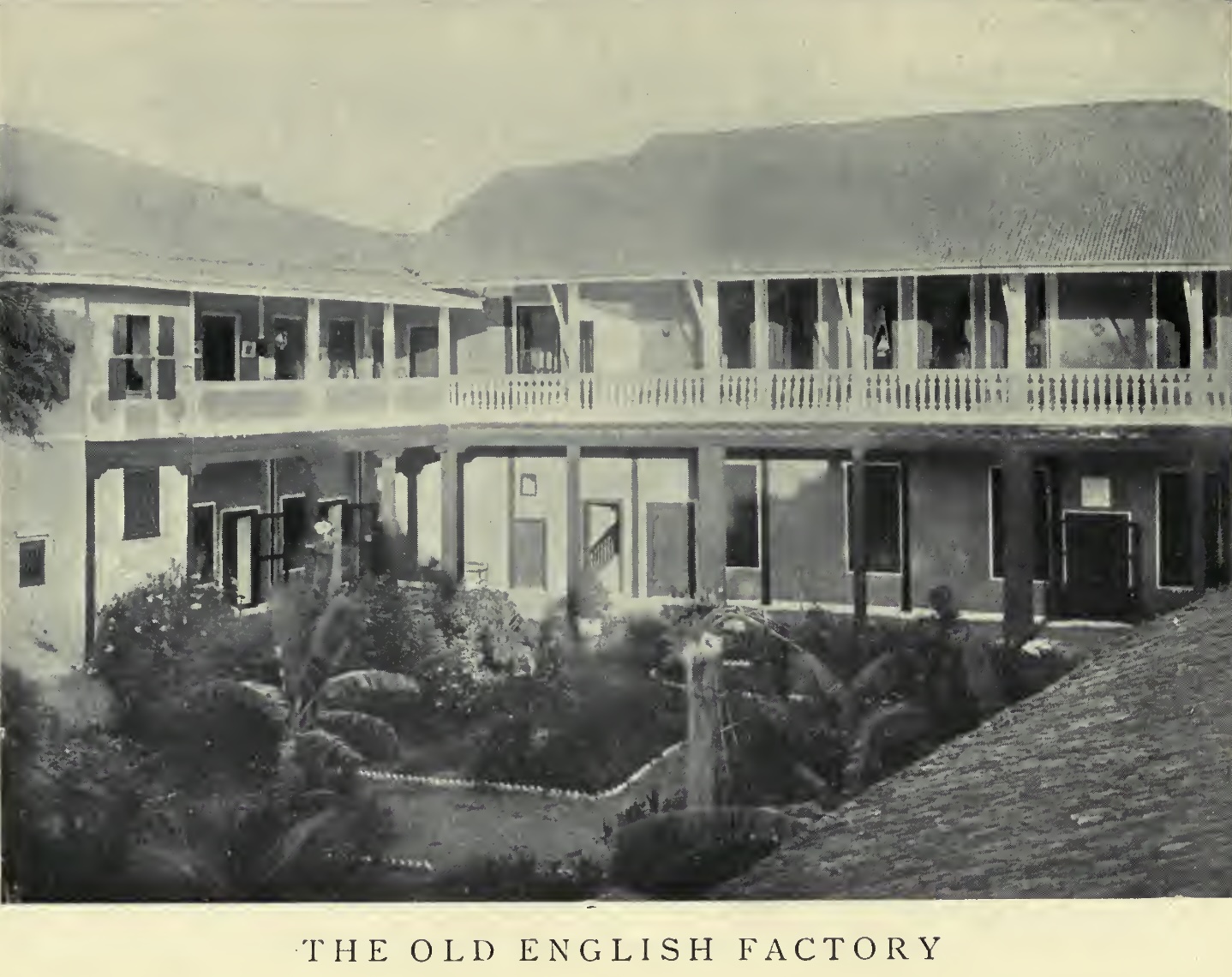

The Merchants Ashore

Aldworth and the factors were now shorn of Best’s defence. Even so, they remained optimistic. Writing to London, they declared,

… through the whole Indies there cannot be any place more beneficial for our country than this, being the only key to open all the rich and best trade of the Indies, and for the sale of our commodities, especially our cloth, it exceeds all others, insomuch our hope is you shall not need to send any more money hither, for here and in the neighbour cities, will be yearly sold above a thousand broad cloths and five hundred pieces of Devon kerseys for ready monies, and being sorted according to our advice herewith sent you, will double itself.

They expected to sell large quantities of quicksilver and vermillion at a triple profit, ivory and lead at attractive prices, and to source indigo, calicoes, cotton yarn and other Indian products at a cost that would yield a threefold profit in England, ‘at least’. To Sir Thomas Smythe, Aldworth declared that Surat was ‘the fountainhead’ from whence the Company might draw all the trade of the East. The town offered merchandise that might be sold all over Asia, as well as in England, which explained why the Portuguese were putting up so much resistance. If King James favoured the Company’s effort, his treasury would benefit to the tune of 200,000 crowns annually, or more, without expenditure of silver.

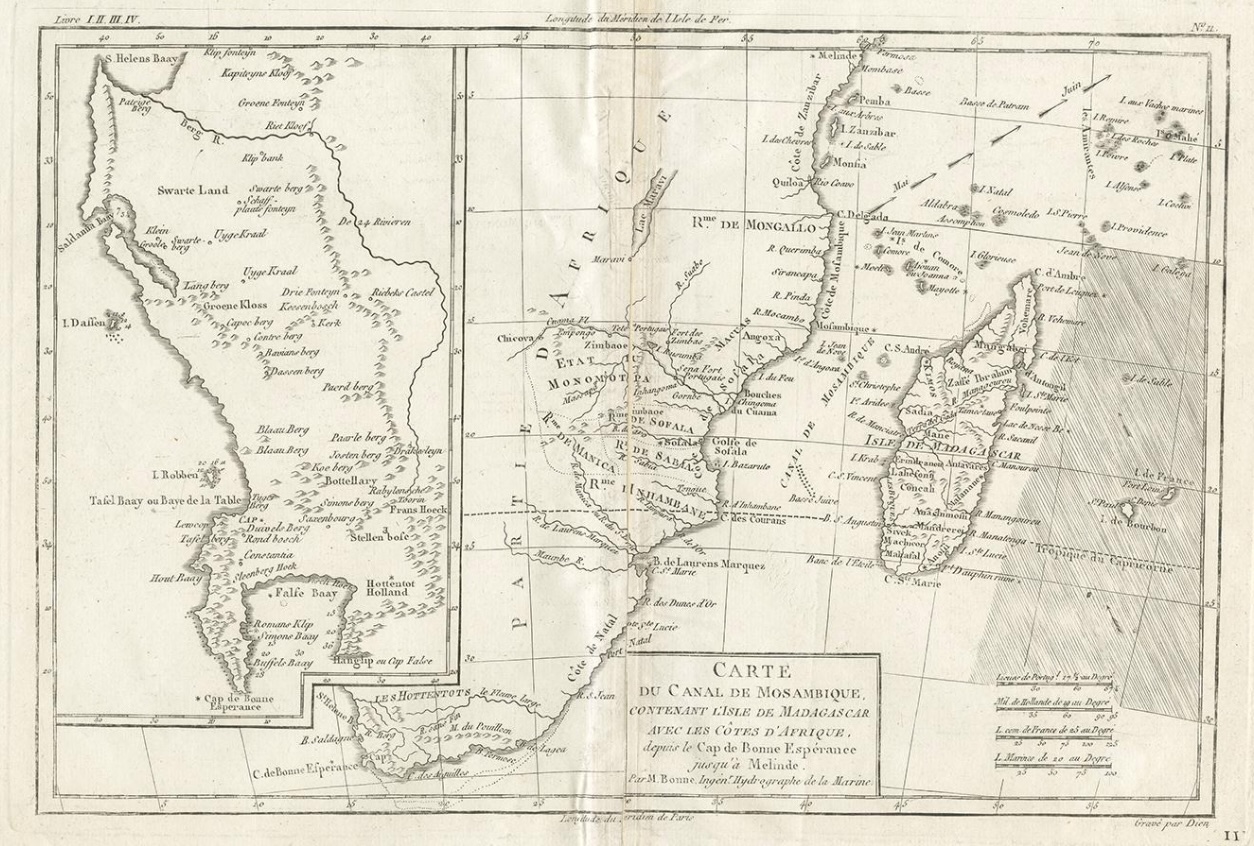

Kerridge was convinced that the Gujaratis favoured the English over the Portuguese. Portuguese sea power kept the Indians in fear, but the Portuguese were ‘disesteemed’ since the fight with Best. It only required the English to assert themselves, and to provide profitable trade, for the Portuguese to be expelled. To support the effort, he advised that a settlement should be established at the Cape, to serve as a revictualling station for English ships. Together, Aldworth and Biddulph proposed that five or six ships should be sent to Surat: they would be sufficient to restrain the Portuguese, whilst allowing two to be ‘furnished herehence with commodities fit for the southward, where it commonly yields three for one.’[24]

The immediate priority, however, was for Canning to procure the emperor’s seal on the articles agreed in Surat. He left at the end of January 1613, in a party which included Richard Temple and Edward Hunt, his cousin Lancelot, and the cornetist Trully. It was an arduous, seventy-day journey in which they underwent many troubles,

… [Canning] beeinge sett on by the ennemye on the waye, whoe shott him through the bellye with an arrowe and likewise one of his Englishmen through the arme, and killed and hurte many of his pyonns (peons).

Canning recovered, but he was deserted by Temple and Hunt, who took his best horse and £20 worth of his ‘furniture’.[25]

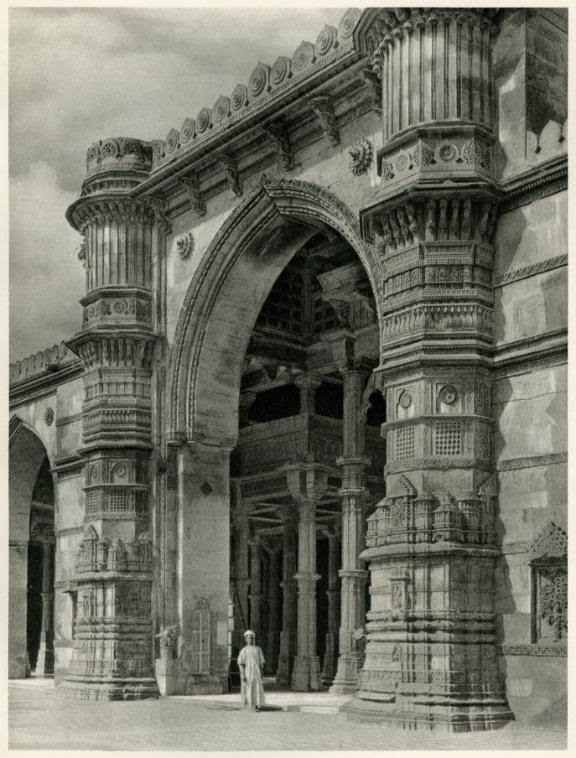

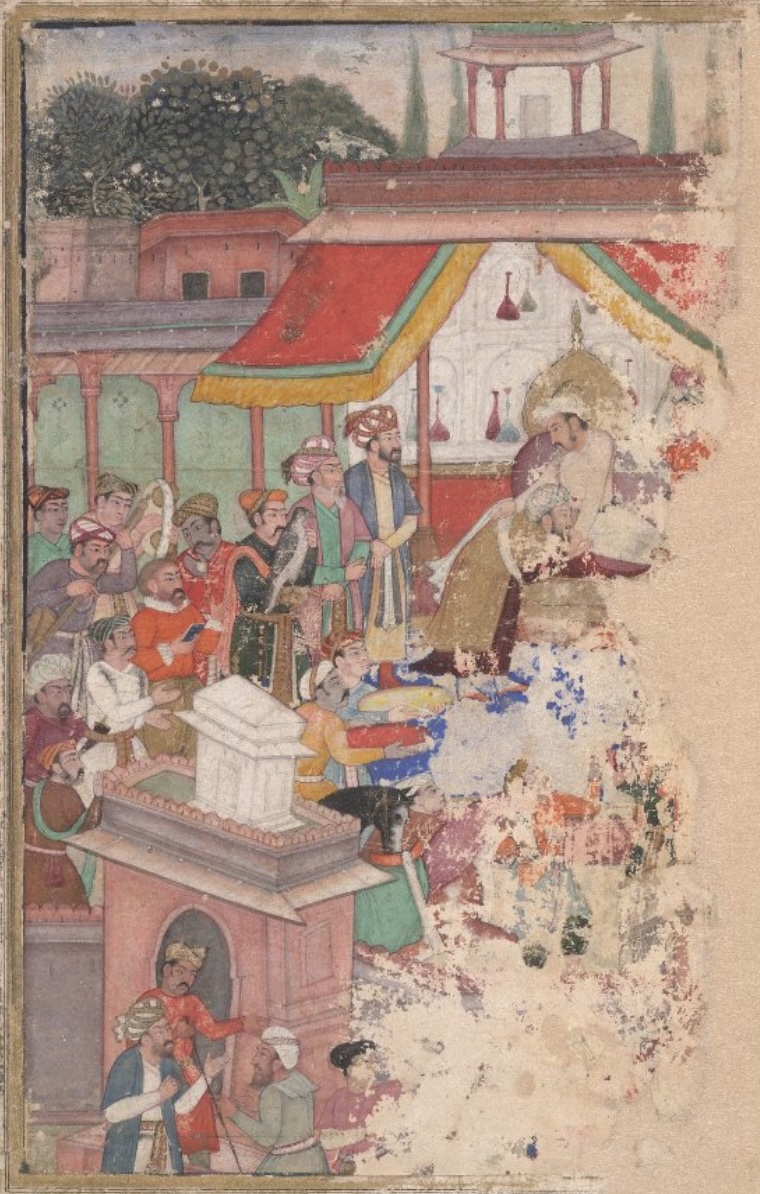

The remainder reached Agra, on 9 April. Called to an audience with Jahangir the next day, Canning presented King James’s letter and presents. As we know, the virginals were judged unworthy. Jahangir asked whether they also came from his monarch, which was unfortunate. Canning admitted they did not, ‘whereof the Jesuits being present made a sinister construction to the king.’ To counter the allure of the cornetist, they produced a ‘Neapolitan juggler’ who, they claimed, had been sent especially by King Philip. The Jesuits knew what appealed to the emperor. Jahangir gave Canning a cup of wine and an assurance that everything would be granted, but his interest was in novelties. The Englishman was asked to write home for more. Then, after a brief discussion of ‘idle and trivial questions’, Canning was referred to Mukarrab Khan, for matters related to business.

Encouraged by the Portuguese, the nabob made several objections: that the English would insist on a large establishment in Agra, that they would seize the merchants’ goods if not satisfied, that they put at risk the trade currently enjoyed with the Portuguese. We are told that all these points were answered to Jahangir’s satisfaction by Canning. Yet, he wrote to Surat expressing fears of poison. Nicholas Withington, he suggested, should be sent to Agra, to provide cover in the event of his ‘mortalletye’. Almost immediately, in May 1613, there was news that he had died and that his goods were being kept safe until someone could take his place.

In August, Thomas Kerridge arrived at Agra. He obtained an interview with the emperor but could interest him in commerce no more than Canning. The only thing that caught Jahangir’s attention, apparently, was Kerridge’s hat, which he surrendered for the cause. He was then referred to Mukarrab Khan, with whom he found it as difficult to treat as had his predecessors. The nabob objected to the damage done by Middleton, demanded compensation, and argued that the emperor’s signature on the agreement was unnecessary. For much of the time, he was unapproachable.

Over the course of the ensuing year, Kerridge came to doubt that he was suited to the role he had been given. What was required was that ‘a lieger be sent to be continually resident in this court, and if possible that he have either the Persian or the Turkish tongue.’ He reminded London of the need for frequent gifts: ‘Anything that is strange, though of small value, it contents him,’ he explained. Reflecting on the loss of his own headgear, one idea he proposed was ‘half a dozen of coloured beaver hats, such as our gentlewomen use.’ Jahangir’s women could use them a-hunting. Fundamentally, however, Kerridge feared for the prospects, unless another fleet arrived shortly, ‘as well to curbe the Portingales as to affright this people whom nothinge butt feare will make honest.’ Aldworth sympathised, but he was more optimistic. Mukarrab Khan had more invested in overseas adventures than anyone. He therefore had most to lose. In addition, Aldworth had faith in English naval superiority. Expressing confidence, he reassured Kerridge,

… that if we should in our persons or goods suffer any detriment in these parts, that thereupon here would come enough of our ships to cover their seas insomuch that neither Moor nor Portingal should stir out of doors and then should [Mukarrab Khan] see whether our King and country were so mean as those lying Jesuits have told him …[26]

Of English shipping, however, there was no sign. Not even of Best’s return. Having filled the Dragon with pepper at Tiku and Bantam, he sailed directly for England, in December 1613. This was galling, because very quickly the Portuguese over-reached themselves. On 13 September 1613, in order to pressurise the Mughals into extirpating the English, they seized the Rahimi as she was returning from the Red Sea:

This shippe [writes Withington] was verye richlye laden, beeinge worth a hundred thowsand pounde; yet not contented with the shippe and goods, but tooke allsoe 700 persons of all sorts with them to Goa; which deede of theires is nowe growne soe odious that it is like to bee the utter undoing of the Portungales in their partes, the Kinge takeing yt soe haynosly that they should doe such a thinge, contrarye to theire passe; insomuch that noe Portungale passeth that waye without a suretye, neither can anye Portungale passe in or out.

Writing from Ahmedabad, Aldworth reported that, such had been the effect of the seizure at Surat, that he had been forced to bring away the Company’s stocks of quicksilver and vermillion, there being ‘no money there to be had.’[27]

The Rahimi was one of the vessels caught in Middleton’s net in 1612 and, then as now, the emperor’s mother had an interest in her cargo. Jahangir took the seizure as a personal affront. Kerridge reported that,

The king here hath caused the Jesuits’ churches to be shut up, debarring them from public exercise of their religion and hath taken their allowances from them, yet their goods untouched, the merchants and their goods embargoed, the ports shut up and no passage by sea.[28]

Mukarrab Khan was sent with an army to besiege the Portuguese settlement at Daman, south of Surat. At the same time, the King of Deccan was induced to attack Chaul, south of Bombay, and Bassein, in southern Burma. In short, there was a concerted attempt to drive the Portuguese out of Asia. The Portuguese responded as they were able, but neither side was able to apply a preponderance of force. The struggle became a stalemate.

In August 1614, Aldworth reported that, in the siege of Daman, the Mughals had razed all the surrounding estates and villages and that, by the destruction, the Portuguese had suffered more in losses than the £100,000 they had obtained with the Rahimi. In response, after burning the towns of Bharuch (‘Broach’), and Ghogha (‘Gogo’) on the Kathiawar side, the Portuguese were assembling an armada to attack Surat. From a personal perspective, he regretted that the town was not better fortified, but he remained confident. The Portuguese had so many enemies ranged against them – Deccanese, Dutch, Mughals, Gujaratis and English – that they would be weak even ‘when they are at best.’[29]

Aldworth was obliged to confess that demand in India for broadcloth had fallen short of expectations. Still, it failed to depress him. Demand for other English goods was solid, and the opportunist Richard Steele, who reached India overland, had assured him that Persian needs would make up the shortfall, at better prices, since supplies sent overland from Aleppo came ‘with great charge’. Moreover, Steele promised that the port of Jask, near Ormuz, offered silk fifty per cent cheaper than Aleppo. If Surat were left with unsold stocks of cloth, all that was required was to take them there, ‘the king of Persia being one that much favoureth our nation … and is of late fallen out with the Portingals.’[30]

In short, Aldworth wrote,

… had we now English shipping here, we might do great good in matter of trade, which is now debarred to the people of this country, having none to deal with them. They all here much wish for the coming of our English ships, not only for trade but to help them, for as they say the coming of our ships will much daunt the Portingals.[31]

Such then was the situation which greeted Nicholas Downton, commander of the Company’s next voyage, when he approached the Gujarat coast. On 25 September 1614, he held a consultation with some Gujaratis off Dabul, who informed him,

… that the Mogull, the Decans and the Mallabars were agreed together utterly to extirpate and roote out the Portugalls out of their cuntry; and that the Portugals had not bin at Cambaya this 12 months; that the Jesuits in the Mogull dominions were by the Mogulls comaundment laid hould on, to have bin put to death, but that Mucrab Chaun begged them, and keepeth them in his campe at the siege of Damon till the Portugales repay the 3 millions of treasure taken in a shipp from Jedda in the Red Sea …

At sea, the Portuguese were refusing to issue passes to any ships of Gujarat, while the Malabars were blockading Chaul with thirty ‘frigats’, and had collected sixty more vessels offshore to interdict Portuguese supplies.[32]

Given the opportunity this presented, we can imagine the joy with which Aldworth greeted Downton’s arrival. At their first meeting, he strived to persuade the commander of the New Year’s Gift ‘that Mocrib Can the Nabob was our friend’ and that the most favourable trading privileges might be obtained. Downton, who had previous experience of Mukarrab Khan, was doubtful, and rightly so. On 24 October, Khoja Nazar, the Governor of Surat, arrived. After the obligatory surrender of gifts (the Company remembered Best’s advice and included a picture of Mars and Venus, as well as one of Paris in Judgement), it became clear that Mughal assistance depended on English aid against the Portuguese. Downton explained that this was impossible, as England and Spain were officially at peace: like Best, he had been forbidden from attacking the Portuguese, unprovoked. This was a complete surprise to the Indians and, when Aldworth visited Mukarrab Khan to explain, he was in no way satisfied. He considered the English responsible for his troubles and he was under pressure to bring his campaign to a conclusion. Bluntly, he told Aldworth that ‘if we would doe nothing for him, he would do nothing for us.’ He was true to his word, and the merchants’ optimism faded.

Downton explored the possibility of taking his business elsewhere, to Jhanjhmer and Ghogha, in Kathiawar. Then, on 2 November, Aldworth reappeared, speaking of reconciliation and free trade. Mukarrab Khan had come to fear that, as a result of his obstructionism, the English would join forces with the Portuguese. (The doubt had been seeded by ‘a knavish device in the subtle and lying Jesuites’ which, unwittingly, Aldworth had caused to fructify with threats of his own.) On 3 November, Downton landed his goods, his council rationalising that Mukarrab Khan’s earlier discourtesy ‘proceeded by his weakness, we not yielding to his unreasonable demands.’[33]

There now arose a dispute between Aldworth and William Edwards, who had arrived with Downton. The Company asked Aldworth to act as Edwards’ second. Aldworth refused to do so. He pointed out that, according to his agreement with the Company, he was to be the chief agent of any factory established during his voyage,

… and that, had it not bene chefflie through his menes in oposeinge Captain Beste, the traide had not bene settled theire at that present.

Aldworth’s opinions about Best had hardened. In a letter to Kerridge, he complained that their earlier correspondence had been withheld from the Directors. Best, he declared, had cast aspersions on all the merchants and had ‘attributed all good services to himself; whereas you know the contrary.’ He was convinced that, ‘if his pride had not been resisted, he had taken the Shahbunder’s ship and so overthrown all trade here.’ To Downton, Aldworth contended that he had run the operations in Surat for nearly two years ‘with mutch dainger of his life.’ He had brought them to reasonable effect, despite numerous difficulties. To be relegated to a subsidiary role ‘woulde be mutch disgrace unto him and cause a jelious conceite of him in the openione of [the] people.’[34]

A compromise was reached. Aldworth would remain in post and Edwards would go to Agra. It was agreed that he was a man of the requisite ‘good fashione and esteem.’ Yet, the title by which he was to represent himself was a matter of some delicacy. William Hawkins had styled himself ‘embassadour’, but this was an exaggerated claim and one the Company was unwilling to sanction officially. Since it was clear that the designation of merchant lacked the necessary kudos, the strictures of the Company created a dilemma. It was resolved with a fudge. Edwards would represent himself as a ‘messenger’ sent by his king. Equivocating on the matter of rank in this way was a delicate trick. After all, if the emperor decided Edwards was an ambassador, Edwards could hardly contradict him. Inevitably, the issue became a source of friction. Nicholas Withington accused Edwards both of exceeding his authority and of failing in his duty. Having adopted the sobriquet of ambassador, before delivering King James’s letter to the emperor, he

… did open the same, addinge and diminishinge what seemed beste for his owne purpose and commoditie, either to or from yt, and soe presented his translation to the Great Mogull, with the present sente him by the marchaunts; and the Kinge bestowed on him 3,000 rupeias (or half-crownes) for horse meate …

After this hee continued in Adgemere … where behavinge himselfe not as beseeminge an ambassador, especiallye sente from soe worthye and greate a prince as the Kinge of England (beeinge indeede but a mecannycal fellowe and imployed by the Companye into those parts), was kicked and spurned by the King’s porters out of the courte-gates, to the unrecoverable disgrace of our Kinge and nation, hee never speakinge to the Kinge for redresse, but carryinge those greate dishonours like a good asse …[35]

This was a repetition of the criticisms made by John Jourdain against William Hawkins. That Edwards ‘assumed the title and qualletye’ of ambassador was a charge levelled also by Kerridge. That he failed to assert an ambassador’s dignity was a complaint of his successor, Sir Thomas Roe, who, in January 1616, wrote that Edwards had,

… suffered blowes of the porters, base peons, and beene thrust out by them with much scorne by head and shoulders without seeking satisfaction, and … carried himselfe with such complacency that hath bredd a low reputation of our nation.

Roe, who was officially accredited, insisted on maintaining ambassadorial authority. The Indians, he said, ‘triumph over such as yield, and are humble enough when they are held up.’ But he was critical of Edwards in other respects:

Here hath been last year a faction and general hatred among all your servants, few speaking well of one another, and crossing your business, so that to your extreme prejudice, not one pound of any sort of goods was bought at our arrival. The principal division was all, except one Robert young and Uflett, were against Mr Edwards; and there are many material complaints made, with which I will not meddle … [except] it were as strange if all others should maliciously join to accuse him falsely without some ground.[36]

One of those who particularly objected to Edwards was Thomas Mitford, who stabbed his chief in the shoulder ‘for some words used.’ (For this, he was put in irons, although his impetuosity was later forgiven by the Directors, as reflecting ‘the fury of his youth.’)[37]

Withington’s criticisms of Edwards were returned with interest. Conceivably, given his inexperience, he might have been treated with greater consideration. In May 1614, Aldworth sent him to Agra to buy indigo. As instructed, he made his purchases by issuing credit in his own name. Two days after he had loaded his caravan, he was told to unwind the transactions, as the factory was unable to send him the funds. The local governor stepped in with support, but Withington’s embarrassment was acute,

… for [my creditors] would heare noe reason, but came cryinge and yawlinge for theyre money, which I had not to give them. They put mee to soe much trouble and greife that made mee almost oute of my witts … Soe deeplye was this greife rooted in my harte, this beeinge my firste imployments and in these parts in soe shorte a tyme to have such creditt to take upp soe much goods on my bare worde and then to break yt and soe consequentlye my credit, that I was ashamed to goe oute of doores.[38]

Worse, immediately prior to this, Withington had returned from a wild goose chase after some merchants who were thought to have arrived at Tatta, near modern Karachi. (In fact, the Company’s Expedition had dropped the Persian envoy, Sir Robert Sherley, at the mouth of the Indus River, before sailing to Bantam.) [39]

Withington departed Surat, in December 1613. Travelling with a group of merchants via Radhanpur and Nagarparkar, a journey of some six hundred miles, he had almost reached his destination when his caravan was seized by the chief who had promised it protection against the marauders of the desert. The merchants were throttled with the tethers of their camels and thrown into a ditch. Withington was spared, because he ‘would doe them noe hurte, wanting language,’ but he was taken into the hills and held captive for several weeks. Finally released, at the end of February 1614, he was robbed a few days later of everything but his breeches and his horse (a bag of bones). There followed a trying journey across the desert back to Nagarparkar, much of which Withington completed on foot, out of respect for his tiring nag. He finally reached Surat, on 18 April 1614.[40]

After these experiences, it would perhaps be surprising if Withington had not taken to drink, or to making money on the sly. Shortly after he returned to Agra, Edwards charged him with both. He clapped him in irons. Withington protested his innocence, but he had his moments. In December 1615, Kerridge wrote of an occasion when,

…one horsbacke [he] came to our dore drunke, but would not com in, fearinge apprehention; cryenge out Jaylors, stand of, jaylers more like a maddman farr then when you sawe him last. None of his gardiants would laye hold one him, all of them denyeng, as not beinge comitted to their charge. Such a confused sending of a prisoner I have not seen. And retorninge to Dergee Seraw, wher he gott his liquour, fell out with Magolls on the waye, that unhorste, beat, and deliverd him prisoner to the Cutwall …

After returning to England, in 1616, Withington referred to the charity which cured him of his malady. It grew upon him, he claimed, ‘partlye through greife which I tooke at theire ungratefull oppression and wronge, and partlye through my loathsome imprisonment.’ Clearly, his distress had been acute. Thomas Roe recommended that he be treated with leniency ‘least necessity force desperat course.’ By this, he meant Withington might ‘turne Moore’, or commit suicide. The Company’s view was that he was more guilty than innocent. Although Withington says that, before taking ship to England, he was acquitted of owing the Company anything, he was arrested on arrival. Even in December 1617, they refused to pay a doctor’s charges for curing his ‘phrenzy’, because of his debts. By 1619, when Withington was still petitioning for compensation, even Sir Thomas Roe despaired of him.[41]

There was also ill will between Edwards and Downton. In one moment of playfulness, Edwards put this down to Downton having been lent a copy of George Withers’ book Abuses Stript and Whipt, ‘wherein he lashes me with Withers’ scourge.’ Yet, at his departure from Swally, Downton was highly critical of Edwards, urging him ‘to take measure of himself with reformation.’ Downton was supported by Kerridge, Edwards by the chaplain, Peter Rogers. Rogers did not approve Downton. He wrote to warn the Company that ‘he is not the man you take him to be touching religion, but a contemner of the Word and Sacraments both’:

I delight not to stir much in the mud of his miry hypocritical courses [he wrote] … but I pray God deliver any minister from travelling with him, and I beseech your Worships (as in conscience I am bound) not to persuade any thereto, for it is impossible almost (unless he be preserved by miracle) that a minister should live outward and homeward bound with him, so basely, carelessly, uncharitably and uncomfortably he shall be regarded, and not only so but abused.

Given the degree of dissension between the merchants, it should not surprise that Sir Thomas Roe, upon his arrival in India, expressed himself ‘sorry to heare of such disorder in the factoryes,’ or that he wrote of his shame that Jahangir knew he had such countrymen. As we have seen, he thought the principal division was against Edwards and, in fact, after he returned to Surat, Edwards was censured by the other factors, suspended from the Company’s service, and sent home in disgrace.[42]

But this is to look ahead. On 7 February 1615, Edwards and Kerridge caught up with the emperor, who was hunting in the field. They presented King James’s letter, pictures of the king, queen and Electress Palatine, a cloak, a case of spirits, an ebony framed looking glass, and a case of knives. (Probably wisely, an English representation of the emperor was discarded. It was not at all in his likeness.). All of these were gratefully received, but nothing more so than a young mastiff, the survivor of several that had been shipped from England:

… and speaking of the dog’s courage, the King caused a young leopard to be brought to make a trial, which the dog so pinched that few hours after the leopard died. Since, the King of Perseia with a present sent hither half a dozen dogs. The King caused boars to be brought to fight with them, putting two or three dogs to a boar, yet none of them seized; and remembering his own dog sent for him, who presently fastened on the boar; so disgraced the Persian dogs, wherewith the king was exceedingly pleased.[43]

To signify his pleasure, Jahangir contributed three thousand rupees towards Edwards’ expenses. Speaking ‘out of sincere affection’, he indicated he would send to King James a letter and a portrait and whatever else was thought fitting. (Kerridge suggested a young elephant.) Two of Jahangir’s senior advisers, Mahabat Khan, his ‘greatest minion’ (later his jailor), and Asaf Khan, elder brother of the new queen, Nur Jahan, responded likewise with increased attention.

Edwards’s account of the audience opens cautiously and becomes more hopeful. Gracious speeches, he began, ‘would put all doubts of fair and peaceable entertainment in your ensuing commerce apart … were they not Moors.’ Still, the firman sent by the emperor to the governors of all the seaports and principal towns (Kerridge says to Surat and Cambay only) promised to be ‘very effectual to the purpose of our trade and fair entertainment.’ In other respects, too, the prospects were positive. It was true that, once the novelty had worn off, demand for English cloth had fallen away: in Surat, it was sufficiently expensive that, ‘for the price of a covett of our cloth a man will … make himself two or three suits.’ Yet, there was interest in the Company’s quicksilver, lead, tin, and sword blades and, from the purchasing point of view, the prices of indigo and cotton were unusually low, as a consequence of the hostilities with the Portuguese. By the end of his letter, Edwards’ advice was to keep the gifts flowing, ‘as there is great hope of a profitable trade in these parts.’

Gifts were a necessary adjunct to trade, to remind the emperor and his aides to be mindful. Yet, Edwards and Kerridge both mention that their reception had been boosted by news of a battle between the Portuguese and the English. Thomas Mitford reports that it reached Jahangir just the day before the audience, adding,

… how we gave them a shameful overthrow with the loss of three of their ships besides many frigates, wherein they lost three hundred men at least, did much commend the valours of the English.

From this, it is clear the battle to which they refer is not that in which Best had been engaged. And indeed, from the end of November, warnings had reached the English at Surat that the Portuguese were meditating something new. [44]

The ‘Warre’ of Nicholas Downton

At that time, Mukarrab Khan, it may be recalled, was hoping for, but not receiving, English support. On 16 December, he complained to Thomas Elkington, commander of the Solomon in Downton’s fleet, that the Portuguese had used their vessels (including the Rahimi) to burn Ghogha. Why, he complained, had Downton not opened fire on them as they sailed past? His suspicion of English intentions intensified, even as Portuguese coastal craft assembled in the Surat River, to test Downton’s position.

The first exchange of fire occurred on 27 December. The next day, some small boats were almost intercepted as they communicated between ship and shore. On 29 December, fearing the Portuguese might have the better of him in the shoals, Downton retreated into Swally. He cleared the decks and freed up his ordnance. By the evening of 18 January 1615, the enemy had been joined by six galleons and three lesser ships. Mukarrab Khan’s resolve crumbled. He sent a gift of provisions to the Portuguese viceroy, as an inducement to halt hostilities. Failing that, he hoped for better terms after the Portuguese had beaten the English. For, as Downton noted in his journal, no one thought it likely that his small fleet could withstand the forces ranged against them. Viceroy Azevedo was no different. In addition, he was convinced that, once he had seen off the English, he would be able to deal more easily with the Mughals. He dismissed Mukarrab Khan’s friendly overtures.

According to Elkington, the viceroy’s fleet comprised six galleons of between eight hundred and a thousand tons, three smaller ships of 150 to three hundred tons, and some sixty armed coastal vessels (‘frigates’). The odds against Downton’s New Year’s Gift (650 tons), Hector (five hundred tons), Merchant’s Hope (three hundred tons) and Solomon (two hundred tons) appeared overwhelming. Yet, as in 1612, the Portuguese were at a disadvantage in tactics, cannon, and in the fighting quality of their soldiers, most of whom were trained for close combat only.

The scale of the Portuguese force surprised Downton, and he had to think carefully about what course to adopt. He considered Best’s approach, but he lacked Best’s faith in English ships’ manoeuvrability, and he feared that, in deep water, a force comprising the principal vessels of the Portuguese would prove insuperable. Close in, the English would be beyond the reach of the enemy’s larger vessels, but they would be vulnerable to fireships. Finally, he resolved that,

… if we should receive a foile riding at our anchor, our disgrace will be greater and our enemies little abashed, but in mooving I might moove the Viceroy in greedinesse and pride to doe himselfe wrong against the sands; hoping that that might bee an occasion whereby God might draw him to shorten his owne forces and so might open the way for our getting out among the rest, which would rather have been for a necessitie then any way hopefull …[45]

Downton’s decision, then, was to engage the Portuguese in the shallows of the Swally Road. As a strategy, it was not without risk. Should the engagement have come to close quarters, Portuguese numbers would have counted for more, English manoeuvrability for less. In confined waters, the viceroy’s armed coastal vessels, which were rowed, had more to contribute. When faced with a possible repeat of the action, in November 1617, Martin Pring, master of the New Year’s Gift under Downton, wrote that he wished to put out to sea, ‘where I may be in a more spatious place than in the poole of Swally; for riding there they have no small advantage against us, if they know their own strength.’ The implied criticism of Downton was made more forcefully by Sir Thomas Roe. Though no naval tactician, he had earlier advised Pring, if attacked by the Portuguese, ‘to putt out … and attend them in sea roome,’ instead of being besieged ‘in a fish pond’. Captain Best, he added,

… with lesse force mett them and beate them like a man, not by hazard; and if he had had that force which Downton had, I beleeve had brought away a better trophee.[46]

Downton might have answered that his imperative was to protect his fleet from harm and, at this early stage in the voyage, to preserve its capacity for earning a return. Yet there was hazard enough in the strategy he adopted when he first made his ‘moove’. For, instead of keeping his force together, he detached the Hope and offered her as bait, to tempt the viceroy into weakening his force. He concedes that his plan almost went awry. It was, he wrote, ‘not altogether of purpose to leave her destitute of our helpe.’ No sooner had he gone below, to write his instructions for the battle, than he heard the enemy were launching their attack. The other English ships were unable to weigh in time, so they had to cut their cables to bring themselves to bear:

… but the enemies ships were aboord [the Hope] and entred their men before we came sufficiently neere them; their men being entred with great shew of resolution, but had no quiet abode there, neither could rest in their owne ships nor make them loose from the Hope, for our great and small shot; so that when the principall were kild, the rest in great number for quietnesse sake leapt into the sea, where their frigats tooke many of them up.

According to an anonymous English account, the Portuguese lost three ships in this action. They were abandoned by their crews and burnt to the water. A number of frigates were also sunk.

Samuel Purchas’ account is the most poetic:

Without feare or wit (saith one of the Hopes men), thirtie or fortie were entered on the forecastle. But the Gift in this fatall moneth answered her name, and gave them for a new yeeres gift such orations (roarations yee may call them) that they were easily perswaded to leave the Hope, and, all hopelesse, to coole their hote blouds with leaping into the seas cold waters; where many, for want of a boat, made use of Charons. Those that were of most hope held still their possession of the entered Hope; but with enterred hopes and dispossession of their lives.

What Christopher Farewell, a junior factor on the voyage, lacks in poetry he makes up in gore:

[The Portuguese] were soundly beaten for theyr haste; for in laying [the Hope] aboord on all parts with throngs of men and fresh supplyes, the master and company (being vigilant and valiant) stoutly resisted [and] gave them so hote entertainment that theyr legs and armes were sent flying into the ayre and the ship pestered with their dead and dying bodies, scorched and wounded with weapons and fireworkes, and theyr bloud issuing out [of] the scupper holes into the sea, as not willing to abide theyr fury.

He claims that, by the end of the engagement, the Portuguese had suffered such slaughter that their dismembered bodies covered the shore and were collected by the Indians, ‘for spoyle’, for days.[47]

In his account, Downton seems to suggest that, before they abandoned their vessels, the Portuguese set light to them, ‘of purpose to have burned the Hope with them.’ Fortunately, the Hope was freed up in time, and the fireships burned themselves out on the sands. Setting his language alongside that of others, however, it is possible to interpret events otherwise. It is possible that the fires were caused by English cannon for, after the initial assault, the two sides exchanged shots across the shoals, for as long as daylight lasted. The anonymous account explicitly states that the three ships were taken by the English and fired by them.

Downton says that, besides the wounded, just five English were killed, and that little harm was done except to the Hope’s upperworks, as the result of an unfortunate accident:

By great mischance the Hopes maintop, topsaile, topmast, and shrouds came afire and burnt away, with a great part of the mainemast, by the fireworks that were in the said top, the man being slaine that had the charge thereof. This mishap kept us from going forth into deepe water to try our fortunes with the Viceroy, but were put to our shifts, not knowing how or by what meanes to get the said mast cured.

The anonymous account explicitly states that the damage suffered by the Hope was the result of a ‘mischance’,

… which was in the tope, the man which was their beinge kilde, his mache (match) fell amongest the powder and wildfier; which burnte hur maste.[48]

Even so, it had been a close thing. Downton boasted that the Portuguese ‘could never get the advantage to winne from us the vallewe of a louse, unlesse our bullets which we lent them.’ Yet, in a letter to the Company, he admitted that they had been formidable opponents and that, if they had not, at the first, ‘fallen into an error’, they might have taken the Hope. Not without reason, did he,

… sencibly see that, had not God foughtte for us and taken our cause on Himselfe to defend, wee had binne sore opprest.[49]

The Portuguese fought with resolution and their deaths were severe. Downton mentions a report that 350 were taken for burial at Daman. He believed that no fewer than a hundred more were killed and burnt in their ships, ‘besides those drowned, which the tide did cast up ashoare.’ Probably extravagantly, Samuel Purchas suggests that, of these, there were between five hundred and eight hundred. Whatever the truth, the Portuguese were disinclined to engage in combat again.

Instead, with the Jesuits interceding, they turned to Mukarrab Khan, offering terms for peace. They found him resolved to accept no conditions from which the English were excluded. Meanwhile, he offered Downton timber and provisions, and facilitated the loading of indigo and other trade goods. In addition, he warned of a Portuguese plot to poison the water supply. As Purchas describes it,

… this was the Jesuites Jesuitisme (I cannot call it Christianitie), who sent to the Muccadan of Swally to entice him to poyson the water of the well whence the English fetched for their use. But the ethnike had more honestie, and put in quicke tortoises, that it might appeare (by their death) if any venemous hand had beene there.[50]

Indeed, so friendly had Mukarrab Khan become that Downton put a more favourable construction on his earlier behaviour: he had been driven to it by command of the emperor, who wished to enforce a first claim on any items the English brought which offered appeal, as gifts.[51]

It helped that the nabob knew the Portuguese were under pressure from the Persians in Ormuz, and from the Malays in Malacca. Detecting a turn in the tide of power, on 3 February, he warned Downton that the enemy were preparing fireships. On the night of 9 February, two frigates towing fireboats were seen approaching from the north. When the English fired upon them, they veered away and released their charges to drift on the tide. Downton wrote,

The first drove cleere of the Gift, Hector and Solomon, and came athwart the Hopes hause, and presently blew up, and with the blow much of their ungratious stuffe; but (blessed be God) to no harme to the Hope, for that by cutting her cable shee cleared herselfe. The latter came likewise upon the quarter of the Hope and then flamed up, but did no harme, driving downe the ebbe, and came foule of us againe on the flood, the abundance of fewell continually burning; which our people in our boates towed ashoare, and the former suncke downe near us by daylight.

Another attack, which did no harm, followed two days later, and (so Mukarrab Khan warned) another was meditated for 12 February. This did not eventuate. More significant was an effort made the day before which, Downton suggests, represented a Portuguese attack on Surat itself. Downton declares that, if the viceroy had followed this through, he would have attacked the Portuguese fleet, to defend the Company’s stock and merchants in the town. In the event, he claims that Azevedo ‘would not trust mee so much as to unman his ships, lest I should come against him.’ Perhaps this is what Thomas Mitford was alluding to when he wrote that Jahangir,

… did much commend the valours of the English, saying that he was endeared unto us for defending his port of Surrat (for of purpose the Portingalls came to have taken it, and so would have done if we had not been there to defend it).

The next day, a new plan was prepared whereby an associate of the Portuguese set up lights ashore to enable their galleons to train their cannon to greater effect at night. Downton, again, was warned and so,

… I sent William Gurdin ashoare with twentie men, shot and pike, to incompasse and take the blaser of the said fire, supposing it to be some traytor inhabiting these nearest parts; who in his passage comming neare it, it would seeme presently out, and againe at an instant at another place contrary to their pursuit; and so playing in and out with them so long that in the end they gave it over, esteeming it some delusion of the Devil, not knowing otherwise how to conjecture thereof.[52]

On 14 February, there came the news that Viceroy Azevedo had departed for Goa, leaving just a few of his vessels to attend the river. Downton had his doubts, suspecting he had withdrawn only to marshal his more powerful ships, the better to deal with the English when they put out beyond the shelter of the sands. Nevertheless, he began to load the Hope with goods for England. The remainder of the fleet was prepared for Bantam. They stayed for a fortnight at the request of Mukarrab Khan, who feared the Englishmen’s leaving would precipitate another attack by the Portuguese. Finally, on 25 February, the nabob came, with a substantial escort, to Swally, to give Downton a send-off. It was altogether friendlier than the one he had given Sir Henry Middleton two and a half years before. Downton wrote,

I purposed to go unto him (as a sonne unto his father) in my doublet and hose, without any armes or great traines according to custome, thereby to shew my trust and confidence that I reposed in him; but my friends perswaded me to the contrary, that I should rather goe well appointed and attended on with a sufficient guard to continue the custome. Whereunto I consented … and went ashoare with about one hundred and forty men, of pike and shot; who at my entrance into the Nabobs tent gave me a volly of shot …[53]

Mukarrab Khan was given a tour of the New Year’s Gift, in which particular attention was given to her ordnance. To commemorate his victory, Downton received the nabob’s own gold-hilted sword. In exchange, he offered his sword, dagger, girdle and hangers. (They made a better show, Downton wrote, but they were ‘of lesse value’.) There followed another exchange of gifts onshore, in which Mukarrab Khan gave the Gift’s gunners and trumpeters some coins in gratitude for their reception of him.

The English departed Swally, on 3 March 1615. Two days later they reached Daman, from where the Portuguese followed. The weather was closing in and Downton reasoned that, if he gave the viceroy a fright, he would turn tail rather than close or threaten Surat. So it proved and, on 6 March, Downton had the pleasure of watching as he and his consorts gave up the chase. To his diary he professed,

I like [it] very well, since he is so patient, for there is nothing under his foot (ie. in his power) that can make amends for the losse of the worst mans finger I have.

According to Antonio Bocarro, the viceroy abandoned his campaign because he learned that the Persians under Shah Abbas had captured Gombroon, opposite Ormuz. With Ormuz itself at risk, Azevedo sailed to Diu so that reinforcements could be sent to its aid. Separately, Manoel Faria y Sousa states that, following Downton’s departure, the Portuguese concluded a peace with the Mughals, by which they offered to pay compensation for the Rahimi, conceded freedom of trade, and granted that one of Jahangir’s ships might trade between Surat and Mocha each year, without paying duties. As a quid pro quo, they proposed that English and Dutch ships should be denied harbour in Indian ports, that they should be expelled from Gujarati waters within three months of their arrival, and that, if they entered Surat’s port, the Portuguese might use their guns to drive them out.[54]

In fact, Jahangir refused to sanction the draft. In July 1615, Kerridge was delighted to write from Ahmedabad of,

… Macrobchans Maye games in Cambaya, settinge a Portingall on an ellephant and in a manner publishinge a peace with them upon incertayne and base conditions (therby to blinde the Kinge).

From Ajmer, Edwards confirmed that the proposals were ‘greatly disliked both by the Kinge and nobillity.’ A little later, he wrote that Goa had been told by Madrid that no peace with the Moghul was to be permitted whilst the English remained in the country. For the Company’s expulsion, he held no fear. Jahangir understood that, in the battle with Downton, ‘most of [the Viceroy’s] ships were burnt by the English fire’ and that, once they had been rendered helpless, the Portuguese had taken to flight. The English had proved themselves powerful competitors. The best policy, therefore, was to let the Portuguese shift for themselves.[55]

The Arrival of Sir Thomas Roe