The attitude of the Dutch was to become a matter of a severe contention, but it would be wrong to assume that Sir Henry’s frustration immediately galvanised a concerted effort by the Company to contest the Dutch monopoly. Even if they had realised that regional exclusivity was being demanded, the Company would have been hard pressed to prevent it. Its capital resources were meagre, and, prior to the first Joint Stock (1613-1616), they were allocated to each voyage separately, which was inefficient. In the succeeding six voyages, just three out of thirteen English ships had the Spice Islands as their destination: the Consent and the Expedition under David Middleton, in 1608 and 1610, and the Hector under William Keeling, in 1609. (John Saris’ Clove stopped at the Moluccas, in 1613, but his target was Japan.) Instead, in this period, the Directors’ principal purpose was to explore a range of destinations, and to get as complete an understanding of the eastern trade as their limited resources permitted.[6]

Because, for all that Henry Middleton might rail at the ‘pride and insolencie’ of the Dutch, the Company faced another particular challenge. Little or no progress had been made in securing a market for English goods, principally woollens. Some fashionable spices had been obtained at a cheaper rate but, without a matching revenue from exports, they would need to be paid for in silver. That antagonised mercantilist opinion, and – given the length of voyages – it placed a strain on the treasury.

Yet, right from the moment at which James Lancaster had captured the Portuguese carrack, Santo Antonio, in 1602, it had been realised that there was demand in the Indies for Indian calicoes. The intelligence was reflected in the instructions issued to Henry Middleton, and it was confirmed by those who returned with him on the Second Voyage. They reported that demand in the islands which supplied the spices was for,

… stuffes or Clothes as our men call them: & called by the Dutchmen kleetghees being the same & such like stuffes as Sir James Lancaster tooke which are made at Bengalla, Mesepatamya, Cheremandalle & St Thome, and as some saye alsoe att Suratt & Cambaya …[7]

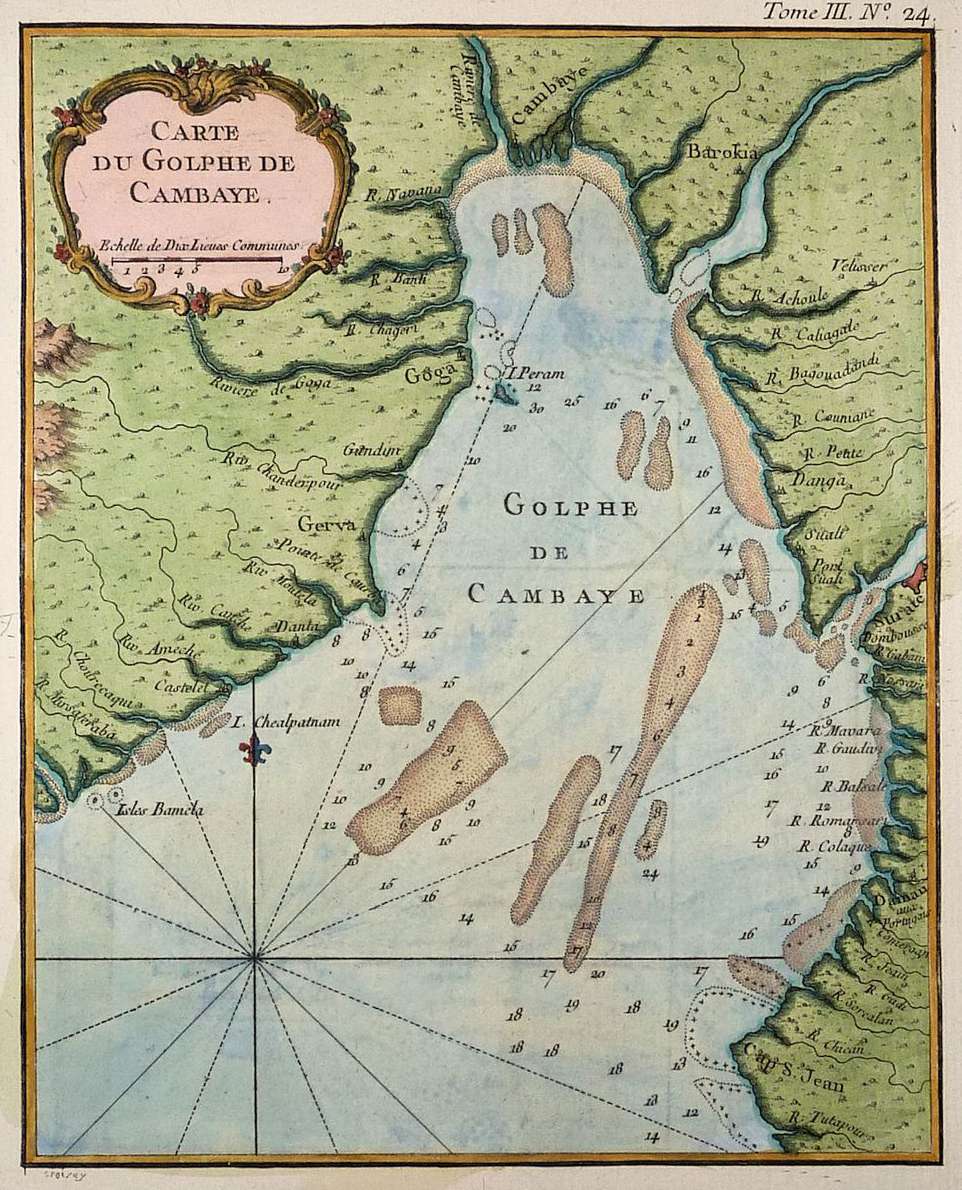

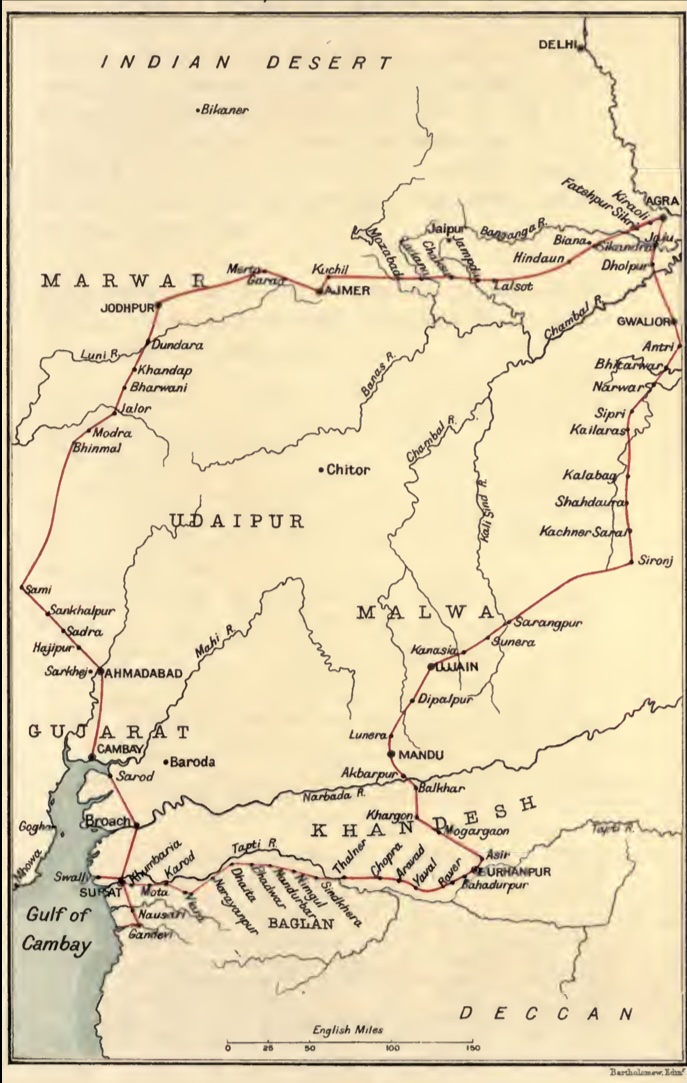

The Company’s solution, in the Third Voyage of 1607, was to focus on the Indian dominions of the Mughal Emperor. A double profit might be obtained if Indian wares could be purchased with broadcloth, and then used as currency for pepper, cloves and nutmeg. In addition, a voyage to the Gulf of Cambay, north of Bombay, could be used to explore opportunities for a factory across the Arabian Sea, in Aden, ‘or some other place thereaboutes’. As every Levant Company director knew, the Gulf ports lay at the heart of trade between India and the eastern Mediterranean. If spices could not be obtained at their source, they might be shipped to Europe from there.

Finally, in respect of the upcoming voyages, there was a hope that the Treaty of London, which ended the Anglo-Spanish War, in 1604, would make the Portuguese in the East more tolerant of English merchants. Even if that were to prove unrealistic, there was the chance that they would rein in their opposition, if the English were trading successfully with powerful Indian princes.

The Third Voyage of the East India Company (1607-1608)

A fleet of two ships and a pinnace was assembled for the first attempt. For its overall commander, the Company selected William Keeling, who had commanded the Susan on the outbound voyage with Henry Middleton in 1604, and the Hector on the return, in 1605-1606. (Nine months after leaving Bantam, she had been discovered off the Cape, with just ten of her fifty-three crew alive, so Keeling had experience of hardship.) In 1607, Keeling sailed in the Red Dragon, with Anthony Hippon, subsequently commander of the Seventh Voyage, as Master. David Middleton, brother of Henry, was given command of the pinnace, Consent. For the ‘lieutenant general’ of the fleet, and captain of the Hector, the Directors chose William Hawkins.[8]

Hawkins was once identified with ‘Young’ William, the nephew of Sir John, and Edward Fenton’s second on the Edward Bonaventure. This is now usually discounted. Unfortunately, our envoy gives away few clues as to his earlier career, other than that he had been in the West Indies, and that he was conversant in Turkish (Persian). Possibly, he spent time in the Levant, perhaps as a servant of the Levant Company, as many in the East India Company did. Despite his rank, nothing in the record of his voyage suggests he possessed ‘Young’ William’s naval expertise. Indeed, when, in 1614, Sir Thomas Smythe, the Company’s first governor, listed those skills which he considered most qualified someone as ‘chief commander’, seamanship was just one of several. A commander, he said, should be ‘partlie a navigator, partelie a merchaunt (to have knowledge to lade a ship), and partlie a man of fashion and good respect.’ In fact, the Court Minutes at the time of Hawkins’ appointment speak only of his role in delivering King James’ letters to the princes and governors of Cambay, and of ‘his experience and languadg’. Probably, the two Williams are not the same.[9]

The Company’s instructions to the men of the voyage are extremely detailed. Trusting the crews to show respect and obedience to their superiors, and love and kindness to one another, they required (inter alia),

… noe blaspheameinge of God, swearing, theft dronkennes or otherlike disorders be used, but that the same be sevearelie ponished, & that noe diceing or other unlawfull games be admitted for that most comonlie, the same is the begining of quarrellinge, & many time murther a just occasion of Gods wrath and vengeance from which the Lord deliver us all ….

… that noe liquor be spilt in the ballast of the shipps or filthines be left within bourde which in heate breedeth Noysome smells, & infeccon, but that there be a diligent care to keepe the ourlopps & other places of the shipps cleane & sweete, which is a notable preservacon of health, wherein the dutchmen doe farr exceede us in Cleanelines to their greate Comendacons & disgrace to our People …

… that at every place where you shall water, & refresh your men you call the Companies together, geaving them seveare warninge to behave themselves peaceablie & Civillie, towards the people of that place (if any be theare) the better to p’cure their ffreindshipp, towards the supplie of your wants, & the like in every place wheare come, least the losse of your lyves & overthrowe of our voyadge pay for your disorders, besides an utter discreditt to our Nation …

We shall see that in Sierra Leone, and in Socotra, Keeling took the last injunction to heart. At Sierra Leone, where Sir John Hawkins had taken his slaves, he took steps to ensure that ‘yf any offence were ffound donne by our men, Justice should be executed.’

Regarding the route, on which James Lancaster offered the benefit of his experience, the voyagers were advised to stop, not at the Cape, but in Madagascar (‘St. Lawrence’). From there, taking care to avoid ‘the fflatts of Judea’ – the Europa Rocks in the Mozambique Channel – they were guided to head for Zanzibar (for ivory) and Socotra, at the entrance to the Red Sea, to obtain refreshing and, if possible, a cargo of aloes and ambergris.

That the Company’s objective was more than just trade, and rather a step in the expansion of its network beyond Bantam, is clear from what follows. At Socotra, a pilot was to be sought for Aden, so that the English could learn about its commerce and its reception of foreigners. If the intelligence obtained supported it, and the monsoon permitted it, Hawkins was to go there and negotiate permission for a factory, drawing on James Lancaster’s Achin agreement, a copy of which he took with him. Should sufficient cargo be obtained there, the Hector was to return to England. The Dragon and Consent would continue to Bantam. On the way, they would stop at Cambay or Surat, to identify a harbour out of the reach of the Portuguese, at which a trade might be established later. Interestingly, they were told not to tarry: principally, this was to be a reconnaissance mission in which the Dragon and Consent might obtain some goods for Bantam. They were expected to stay ‘some few daies’ before continuing their ‘speedie’ course. Evidently, without Hawkins, it was felt necessary to defer the idea of establishing a factory; no one other, apparently, had the skills to handle the negotiations.

If Aden could not be managed, all three ships were to sail to Gujarat, where the Hector and Consent would endeavour to trade, and Hawkins would try to negotiate rights for a factory, to be run by Antony Marlowe, William Finch and Mr. Pennell. The Consent would lade for England, the Dragon would sail directly to Bantam and, if possible, the Hector with Hawkins, would return to Aden, with the monsoon, before continuing her journey.[10]

In the event, Keeling and Hawkins sailed with just two ships. ‘The Consent held no concent with the Dragon and Hector,’ as Purchas succinctly puts it. David Middleton was convinced that ‘the evill condicion of his shippe’ would make her slow, so he set off on his own. Events were to prove him a model of nautical efficiency. He left Tilbury on 12 March 1607, and anchored in Bantam Roads on 14 November, after a voyage of just eight months. By the beginning of January, he had reached the Moluccas. There he started trading, albeit at night and on the sly, with the natives. In April, at Butung in Sulawesi, he bought sufficient cloves from a passing junk of Amboyna to fill the Consent’s hold. On 2 May, after a week of feasting with the king and his family, Middleton ‘gave the Towne of Buttone three pieces of Ordnance for a farewell’ and sailed to Bantam. By 15 July, he was on his way home. His passage was so quick that, when he next reached Bantam, in the Expedition, on 7 December 1609, he only narrowly missed Keeling, who was just beginning his return voyage. Keeling, he says, passed him in the night.[11]

The Red Dragon and the Hector left the Downs on April Fool’s Day 1607, two weeks after Middleton. Keeling was a slow sailor. Having missed the best of the trade winds, the fleet spent April and May crossing to Brazil, before being ‘inforced by Gusts, Calmes, Raines, Sicknesses, and other Marine inconveniences’ to return to the north.[12]

By the end of July, after sailing to and fro, to recover the isle of Fernando de Noronha (first sighted on 6 June), water was low and scurvy rife among the men. A council was called to consider what was to be done. The mood was depressed. According to Anthony Marlowe,

Trewly to have seene ye sorrowe and some weete eyes amongst us, wch the greefe of theise maters procured, our Cheeffest in England will hardly beleeve.

Between them, the masters and their mates were able to suggest ‘the coast of Brazil, the coast of Guinea, the Isle of Mayo, Cape de Verde, and the little Island by it;’ even, in the case of William Taverner, mate to Master Hippon of the Dragon, a return to England – which, according to Keeling, surprised no one. Taverner had a way of riling the ships’ masters. Later, at Socotra, when Keeling tried to make peace between them, he received a curt rebuff. The Hector’s Matthew Mollineux was heard whispering to the merchants that,

… he had kept a dram [of poison] in store for him of a long time and a poniard in pickle for the space of six months and this day he had sent for it by his boy of purpose to give the stroke and he was out of doubt if he did but touch him in any place it was of such virtue it would speed him.[13]

Off the coast of South America, Keeling consulted his Hakluyt and was inspired by the circumnavigations of Drake and Cavendish to propose the coast of Africa. Purchas argues that this decision saved the Company £20,000, ‘which they had bin endamaged if they had returned home, which necessitie had constrained, if that Booke had not given light.’ ‘M. Hackluits books of Voyages are of great profit,’ he wrote.[14]

On 6 August, the fleet was greeted, at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River, by some natives waving from the shore. Keeling sent a present of ‘an end of Iron & a sherte’ to Captain Pinto, commander of the Portuguese settlement. Pinto responded with ‘a hupe of gould, of about 6 shillings valew’ and a promise of assistance. The country was poor, however, and supplies fitful. On 17 August, to move things forward, Keeling sent Pinto’s son with John Rogers, of the Hector, who spoke Portuguese, with a gift for the king of a bottle of wine, a little calico, and an end of iron. We are told he,

… would leave noe meanes [un]attempted wch might procure ffreshe meate ffor our weake men, ffor as yet wee could gett not anye refreshment save water, a ffew smale henes, ffishe, and lymes.[15]

It is not clear that this generosity produced much change in the diet beyond, chicken, fish, and fruit, but the men’s condition improved. Like Lancaster in the First Voyage, Keeling made a point of dispensing lemon water to his crews, as a cure for scurvy. For that, his men could be grateful. Lemons were to be had in plenty: the Portuguese had planted groves of them near the shore, and sheds had been set aside for the preparation of the antiscorbutic.

According to the merchant William Finch, there were also oranges, plums, ‘mansamillias’ (‘full of sappe, perillous to the sight’) ‘beninganions’ (‘reddish on the rinde, very wholesome’), and

… certaine fruits growing sixe or eight together on a bunch, each as long and as bigge as a mans finger, of a browne yellowish colour, and somewhat downie, containing within the rinde a certain pulpie substance of pleasant taste; I know not how wholesome.

‘Beguills’ were the size of an apple, had a rough, knotty skin and, when peeled, tasted like strawberries. ‘Golas’ received special mention, for the manner with which they were shared:

It is hard, reddish, bitter, about the bignesse of a Wal-nut, with divers corners and angles: this fruit they much set by, chewing it with the rinde of a certaine Tree, then giving it to the next, and he having chewed it to the next, so keeping it a long while (but swallowing none of the substance) before they cast it away.

The natives used golas in lieu of currency, ‘this happie-haplesse-people knowing none other.’ Additionally, they were considered ‘a great vertue for the teeth and gummes’ and, in evidence, Finch tells us the people were ‘usually as well toothed as Horses.’ Mysteriously, he also mentions a strange beast, frequently seen at night. He describes it as,

… having a stone in its forehead, incredibly shining and giving him light to feed, attentive to the least noyse, which he no sooner heareth, but he presently covereth the same with a filme or skinne, given him as a natural covering, that his splendor betray him not.

The Portuguese mission had been established in 1605 by the Jesuit, Baltasar Barreira. (It closed with the death of his successor, in 1617.) King Burrea had been baptised ‘Philip of Sierra Leone’ at its beginning, but Marlowe says his attire was limited to ‘a poore torne Coate wch scasely would hange together, not worth one penny.’ His house, he added, ‘god knoweth was a poore place ffor a kinge.’ Even so, he ruled a dominion stretching forty leagues inshore, and he had several tributary chiefs who paid him in cotton cloth, elephants’ tusks, and gold. Some of the people had been converted by the Portuguese, although the king reserved the right to sell them for slaves and, in fact, he offered some to the English. (The inference is that they were refused.) Finch says the men were big, well set, and strong, ‘of a civil-heathen disposition’:

They are all, both men and women, raced and pinked (tattooed) on all parts of their body very curiously, having their teeth also filed betwixt, and made very sharpe. They pull off the hair growing on their eye-lids. Their beards are short, crispe, blacke, and the haire of their heads they cut into allyes and crosse pathes; others weare it jagged in tufts, others in other foolish forms; but the women shave all close to the flesh …

I could not learne their Religion what it is: they have some Images, yet know there is a God above: for when wee asked them of their woodden Puppets, they would lift up their hands to heaven; more they knew not: but howsoever it comes to passe, their children are all circumcised. They are very just and true, and theft is punished with present death.[16]

Given the last, it was a cause for concern when a threatening group of natives came into the camp set aside for the sick. A spokesman signalled with eleven short sticks, and in broken Portuguese, that some great injury had been suffered by his people. Because of it, they had taken hostage one of the crew, Walter Stere, who had wandered off while searching for wood. An investigation was held by Keeling and Hawkins. They discovered that William Jones, an ‘old theeffe’ who confessed to having narrowly escaped the gallows three times before, had stolen two brass basins and some other goods (eleven in all). These he had buried in the sand by the village. He was required to return them, with two pieces more. He was then ducked from the yard arm. Others were strapped to the main capstan with weights tied around their necks,

… Wch soe well pleased [the natives], as they liftinge upp their eyes toward heaven, humbled themselves at our Generalles ffeete, to the ground, in thankefulness of the Justice receaved.[17]

Shortly before departure, one other offender managed to slip away. George King was accused of stealing some shirts. He had form,

… having lately received his tryalle for a wicked ffackt, not ffitt to be named, whoe vengeance did foollowe ffor his ungodly life past, having as he conffessed bene 3 tymes at the Gallowes ffoote to be hangd. But nothing greved his Conscyence as he sayd but the Robbing of his owne poore mother of 5£.

The night following his arrest, King attempted to escape in a long boat, but he was caught, bound, and brought aboard the Dragon. The next morning, in Hawkins’ presence, he was examined ‘under torment’, and confessed. Keeling ordered that he be confined in the bilboes below decks but, as he was being taken there, he asked his escort ‘if he might goe to the Beacke head to ease himself’:

… and being theare, (as all men Judged) did wilfully cast him selfe with his ffeete fforemoste, throughe a hole into the sea, not having the ffeare of god before his eyes, did cast him selfe awaye and was never seene after, althoughe soe sonne as it was perceaved, all did what they could to have saved him yf he had rysen agayne.[18]

The English stayed in Sierra Leone until 14 September. Before sailing, Keeling had a stone commemorating his visit set up on shore, as he understood Sir Francis Drake and Thomas Cavendish had done before him. Before leaving with them, it is also worth noting one of the earliest recorded amateur productions of Shakespeare’s plays. On 5 September 1607, the crew of the Red Dragon performed Hamlet before going ashore to shoot an elephant. Later, on 29 September, Keeling invited Hawkins to dinner on board the Dragon ‘where my companions acted Richard II.’ Later, in March 1608, Hamlet was staged a second time, Keeling noting that he permitted the show ‘to keepe my people from idlenes and unlawfull games, or sleepe.’[19]

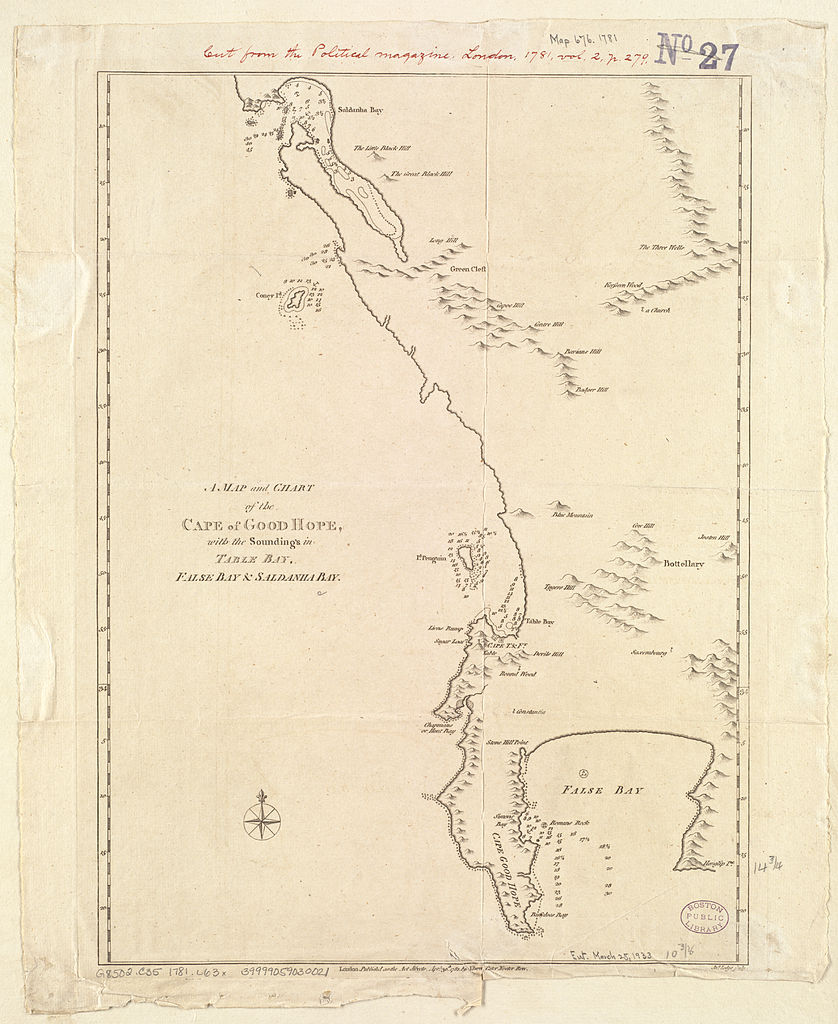

Hereafter, despite the stage shows, the voyage continued long and tedious. It was Christmas before, at the insistence of the weak crews (and against Keeling’s explicit instructions), the fleet stopped at Saldanha Bay near the Cape. Reporting that he found there a rock inscribed by David Middleton, on 24 July 1607, Keeling was good enough to admit he was a full five months behind the Consent. Worse, whereas the people in Sierra Leone had shown ‘all the kyndnes that might be expected at the hands of such a black heathen nation,’ the Saldanians were judged, rather as Lancaster had found them, much given to ‘filching and stealing’. At least Christmas dinner was good value: ‘a good large beef the price but a piece of an old hoop of iron not worth 2d. in England, and good sheep after the like rate.’

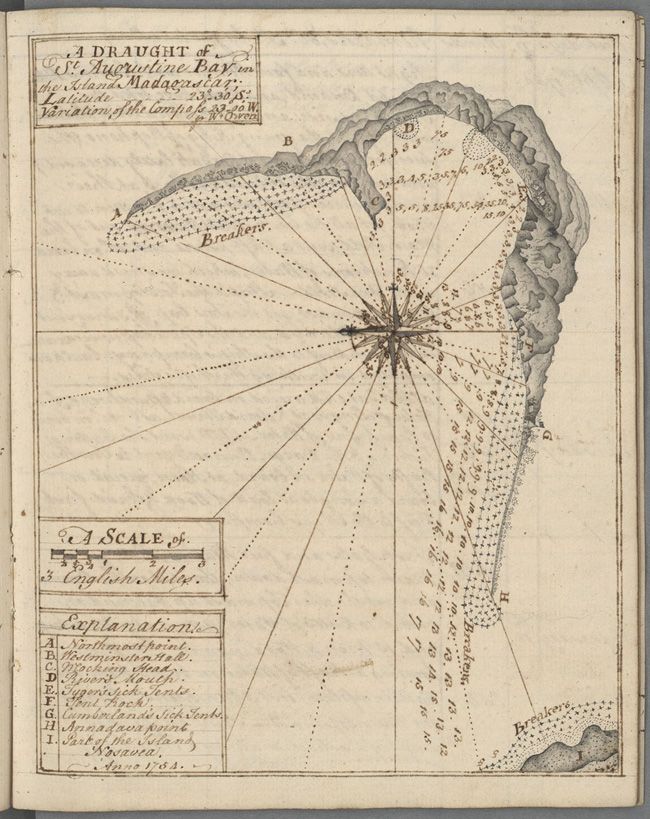

On 1 January 1608, the fleet sailed on in better heart, although the Dragon’s excess ballast made her labour heavily. On 14 January, having rounded the Cape, she and her escort nearly stemmed into one another during a storm, but they were spared disaster and, five days later, they came to anchor in the Bay of St. Augustine, Madagascar. To Hawkins, this was an ‘ylfavoured hole, wheare wee could see nothinge worth commendacions to our purpose.’ Twice the Dragon lost her anchor; one of her crew, his foot. Hawkins made a trip ashore and, returning to the beach, he found George Evans ‘shrewdly bitten with an Alegarta’:

[It] had seised upon the mannes legge … as hee had benne washinge a sherte by the boate’s side, and tugged him over a river, beinge shoale water; but hee, finding himselfe in such sorte, halled away, and being amassed footed the crokadile with his other foote, and soe by greate chance bracke from him sore wounded and recovered the boate, mackinge no other accounpte but that his foote was gonne, till he sawe yet the hinder parte of the small of his legge was bytten cleane asunder both flesh and synewes to the bone; and had the alligator got him into deeepe water, assuredly he had bene carried clene away.[20]

Compared to the people of the Cape, the Madagascans were understanding, sweet and clean, without ‘any filthiness on their heads or their bodies.’ They were also ‘of Subtill and Ingenious wit’ and had a good understanding of silver. They realised when they were being offered something less precious, such as pewter and ‘toyes made of tin and lead, which they knewe presently to be base, and of small vallew.’ Remembering the fleet’s instructions, and the fecundity of the Cape, Finch had some advice to offer those organising future expeditions:

… I hope that hereafter our owners at home will not prohibit touchinge at the Cape in hope of reliefe at any other place whatsoever, considering that the touchinge there (although it bee for a shorter tyme) doth so much importe the good of the voyage, both by preserving of men’s healths by refreshinge in harbour, as also there may be flesh saved, in the manner as were done in the West Indies for 6 weeks victualls at the least.[21]

In Marlowe’s opinion, if Keeling had not stopped at Saldania, the voyage would likely have been ‘utterly overthrowne’.

Writing, as was his wont, of the fauna of the island, Finch mentions lemurs ‘as big as Munkies, ash-coloured, with a small head, long taile like a Fox, garled with white and blacke, the furre very fine.’ He also gives an early description of a chameleon, which he observed hunting a fly in a very strange manner:

Having espied her setting, he suddenly shootes a thing forth of his mouth (perhaps his tongue) lothsome to behold, the fashion almost like a Bird-bolt, wherewith he takes and eates them, with such speed, that a man can scarsly discerne what he doth; even in the twinkling of an eie.[22]

The fleet left Madagascar at the end of February 1608. The voyage to Socotra took approximately two months. It was relatively uneventful, although tempers on the Hector became frayed, and at one point they threatened to boil over into something more serious. On 4 March, shortly after the ship’s feisty carpenter came to blows with John Ashenhurst, his carpenter-mate (Lantro) floored Thomas Rourke, Hawkins’ page, with his fist. The first two were let off with a warning, but Hawkins felt that Lantro should be punished at the capstan, on the understanding that Rourke had done nothing wrong. It seems, however, that Rourke was generally judged not to be blameless, and the decision went ill with the crew. As Lantro’s arms were being bound and a basket of shot was being prepared to be hung from his neck, they came on deck,

… and wth one voyce sayde murmuringly, that they did Labour and should be punyshed evrye boye abusinge them, and growing verye discontented.

The language is a little obscure, but it would appear that Hawkins then backed down. Marlowe says that he thought that ‘the baskett had bene on him, wch was not,’ and that he did not intend that Lanto ‘should taste of the punishment according to his desert.’ He was released.

Like his master, Lantro was a spirited character. Later, in April, he ‘was duckt 3 tymes at Mayne yard arme, ffor geving our Master (Mollineux) a blowe under the eare.’ This followed a like incident, in which Mollineux struck the carpenter ‘a smale blowe uppon the head’ with a hammer, for ‘some word spoken comparativelye in evell parte.’ The incidents passed over but, despite the tit-for-tat, it seems that Marlowe believed Hawkins’ judgement on the earlier occasion merited criticism.[23]

Eventually, more than a year into their journey, the fleet reached Socotra, on 22 April. Stopping first on the western side, Keeling took a troop of a hundred men into the town, but found that the population, fearing they were Portuguese, had fled to the hills. The Englishmen explored the houses, a church and a mosque, in which there were found ‘some poore goodes, and … some seromoyous thinges as Crosses and such like.’ Keeling issued strict instructions that everything was to be left alone. ‘All gentlenes [was] to be used to all people, thereby to recover the scandale, wch Hollanders and Portingales hathe brought uppon us,’ he declared. They returned to their ships and sailed to the north coast, where they anchored opposite the town of Tamore (Hadiboh). There they were treated kindly by the king and obtained some victuals.[24]

There was a plentiful supply of dates (after which the town was named) and aloes, made of the herb sempervivum. These, in season, attracted traders from Portugal as well as Gujarat, as did a more limited supply of ambergris and of civet cats. The population of this generally barren island was thought to comprise about three thousand natives, who eked out a life of slavery in the mountainous interior, and some three hundred Moorish soldiers of the Prince of Caixem, from the Yemeni side of the Gulf of Aden. One of his predecessors had conquered the island about a century before.[25]

‘Tawney, industrious, civill in gesture’, the Arabs were noted for their long hair and for the crooked daggers which they wore on their left side. Finch comments that some of their women ‘were reasonable white, much like to a Sun-burnned countrey maid in England.’ Otherwise, he regretted their habit of using a cloth (‘when they lust’) to hide their faces, ‘making very dainty to be seene, yet are scarsly honest.’ He adds that, although the men were poor, their women were,

… so laden with Silver, and some also with some Gold, that I have seene one not of the best, which hath had in each eare at least a dozen of great Silver rings, almost like Curtaine rings, with as many smaller hanging in them: two Carkanets or chaines of silver about her necke, and one of Gold bosses; about her wrists, tenne or twelve Manillias of Silver, each as big as ones little finger, but hollow, one about another, on one arme: almost every finger laden with rings, and the small of her legs with silver rings like horselockes. And thus adorned, they cannot stirre, but they make a noise like Morris-dauncers.[26]

At Tamore, the English encountered a Gujarati ship, whose pilot provided useful intelligence on navigation, which Keeling recorded in his journal. Other Gujaratis were entertained on board the Dragon. They offered encouraging reports of Aden, and advice on the commodities which sold best, but the arrival of the seasonal contrary wind meant the objective had to be abandoned. After a consultation, it was decided to head East. Keeling sailed straight for Priaman and Bantam, Hawkins for Surat.[27]

In a letter to the Directors in London, Marlowe commended Keeling’s effectiveness as commander. No man, he suggests, could have done better ‘both for the speeding of the voyage, and care of his men.’ Given that, by 22 June, David Middleton was already within three weeks of departing Bantam with a cargo, ‘speeding’ may not be the fittest term to have used. Yet, Marlowe was nervous at the prospect of having to rely on Hawkins without Keeling to guide him. He wrote,

[Keeling’s] wisedome, Language, and Carriage is such, as I fere wee shall have great want of him at Sowratte, in the first settling of our trade. Captayne Hawkins, nowe he Cometh to be left to himselfe, I hope in God will performe your Worships expectations, in the service he Comes for.[28]

The Hector, her hold – on the advice of the Gujaratis – filled with as much of the Dragon’s cargo of lead and cloth as she could carry, reached the Tapti River, on 24 August 1608. On that day, she became the first English ship to anchor at an Indian port.

William Hawkins at Surat

Hawkins stepped ashore in the style he thought would reflect best on the king and country whose ‘embassadour’ he rather grandiloquently claimed to be. No doubt he was decked out in the violet and scarlet suit, and cloak lined with taffeta, which he had been awarded by the Company. He declares that ‘after their barbarous manner’ he was kindly received by the multitudes who came to observe his party – people they had never seen before, but about whom they had heard much.[29]

He was collected in a coach but, as this made its way to the governor’s residence, it was intercepted by the harbourmaster, who told Hawkins the governor was unwell. Hawkins’ own opinion was that he was more likely ‘drunke with affion or opion, being an aged man.’ He resigned himself to having to wait until morning. The following day, he presented his credentials and a request ‘to have league and amitie with (the) king, in that kind that his subjects might freely goe and come, sell and buy, as the custome of all nations is.’ Disappointment followed. Hawkins was told such matters were the province of Mukarrab Khan, the official in charge of seafaring, who was away at Cambay. Application was made, but it took twenty days for an answer to arrive, because of the monsoon. The Englishmen’s chattels were moved to their living quarters, the porter’s lodge of the customs house. Their trunks were ‘searched and tumbled’ by crowds of inquisitive locals, to their considerable dislike. It was therefore a relief to be invited to dinner at the house of a Turkish-speaking merchant.

The host’s ship, it transpired, had recently been captured by Sir Edward Michelborne, the English interloper who – despite the Company’s monopoly – had been granted a licence to trade in the Indies by King James, in 1604. According to William Finch, the evening started with ‘great cheere’, but there was ‘sowre sawce’ when the host captain’s experiences became known. Hawkins used an approach akin to Gabriel Towerson’s, when he was faced with the identical challenge in Bantam. He blamed the Dutch. Fortunately, although Mahdi Kuli knew the truth to be otherwise, he was magnanimous enough to say, ‘there were theeves in all countries’ and that it would be wrong to ‘impute that fault to honest merchants.’[30]

While he waited for word from Cambay, Hawkins was permitted to buy and sell goods for the Hector only. A grant of future trade and for the establishment of a factory, he was told, would require the emperor’s approval, best obtained if Hawkins were to make the two-month journey to the capital to deliver King James’ letter in person. The hope, implicit in his instructions, that Hawkins’ mission would involve just a brief stay on the coast was rapidly fading. Soon, Mukarrab Khan’s brother appeared on the scene. He offered to help select some goods to offer as gifts to Jahangir. This was a scheme that Hawkins penetrated immediately. ‘These excuses of taking goods of all men for the King,’ he declared, ‘are for their owne private gaine.’ Next, the governor told the town’s senior merchants to value the other goods ‘upon their conscience’ before delivering them to his house. This was another very transparent ruse. Hawkins denied his consent for a full three days before being forced to make concessions. Unsurprisingly, Finch considered the merchants’ valuation was ‘at a farre under rate.’ Pointedly, he says the Portuguese were hawking about English piece goods, at half their cost. Worse was to come.

To prepare the Hector for her onward voyage, Hawkins unloaded her ballast of lead and iron and purchased, for cash, some goods suited to Bantam. Anthony Marlowe was appointed her commander, and, on 2 October, he was sent with the goods and some men in two boats, to ready her for sailing. Hawkins continues,

The next day, going about my affaires to the great mans [ie. Mukarrab Khan’s] brother, I met with some tenne or twelve of our men, of the better sort of them, very much frighted, telling me the heaviest newes, as I thought, that ever came unto me, of the taking of the Barkes by a Portugal Frigat or two, and all goods and men taken, onely they escaped.

Marlowe’s boats had been intercepted by a flotilla of the armed coasting vessels used by the Portuguese to ferry goods between Goa and Cambay. When the Portuguese invited the English to cross over to talk with them, Francis Bucke, in one boat, was foolish enough to take them at their word. As he moved over to parley, his boat ran aground and he and nineteen others were seized. A little earlier, the coxswain of the other boat had declared himself up for a fight, but Anthony Marlowe had overruled him. The Portuguese, he said, were their friends. Now, however, they took to flight,

… and [Finch writes], notwithstanding the Portugall Bullets, rowed her to Surat. Foure escaped by swimming and got that night to Surat, besides Nicholas Ufflet and my selfe, neere twentie miles from the place. Yet had we resisted, we wanted shot, and in number, & armour they very much exceeded us.

Samuel Purchas was unpersuaded by Finch’s defence. ‘This not fighting,’ he complained, ‘was upbrayded to our men by the Indians with much disgrace.’ The Portuguese, for their part, were quite matter of fact about their position. Their captain, with ‘peremptorie words’, declared ‘the King of Spaine was lord of those seas, and that they had in Commission from him to take all that came in those parts without his Passe.’ So much for the Treaty of London.

Hawkins expostulated in a letter to the Portuguese captain-major, a ‘proud rascall’ who responded in kind, ‘most vilely abusing his Majestie, tearming him King of Fishermen, and of an Iland of no import.’ As to Hawkins, he gave not ‘a fart for his commission.’ The next day, in a contretemps with another Portuguese, Hawkins inveighed against this officer as a ‘base villaine, and a traytor to his king.’ If he had the courage to come ashore, he blasted, he’d prove it in combat. This had some effect. Onlookers, seeing Hawkins was ‘much mooved’, persuaded the Portuguese to retire. Two hours later, he returned, promising that the Englishmen and their goods would be restored. Hawkins mellowed. He treated the officer kindly, and promised him much, but it did him no good. Before they departed, the Portuguese sent everyone and everything to Goa.[31]

The Company men resigned themselves to the long haul. The Hector left for Bantam on 5 October, leaving Hawkins, a sickly William Finch, two servants, a cook, and a boy, to do their best for England.

By now, Mukarrab Khan had appeared. As long as the Hector was in view, he was as affable as could be. Once she sailed, and payment had been demanded for the goods he had chosen, the dissembling ended. It did not take Hawkins long to realise that the person he was dealing with was in league with the Portuguese. Together, he says, they plotted ‘to murther me and cosen me of my goods.’ He details two attempts on his life. The first occurred at a feast hosted by an Indian merchant and his followers. Three Portuguese came to his tent armed with rapiers and pistols, and called for the English captain. The merchants drew their weapons and put them to flight. Hawkins says they did well to escape to their ships. On the second occasion, thirty or forty Portuguese sought out Hawkins at his home. They were accompanied by a Jesuit priest, Manoel Pinheiro, who came ‘to animate the souldiers and to give them absolution.’ But, Hawkins says, ‘I was alwaies wary, having a strong house with good doors.’

After this, Hawkins complained to the Surat Governor and obtained his support. The Portuguese were told that, if they came armed to the city again, it would be at their own peril. Mukarrab Khan was left with no option but to issue to Hawkins with a licence and letter of introduction to the emperor. Hawkins prepared for his journey. All that was required was for Finch to overcome his dysentery. By the beginning of February 1609, he had done so, and Hawkins departed for Agra.

Hawkins at Jahangir’s Court

Of the journey, he says surprisingly little: mostly he speaks of the way his Pathan escort, and his faithful interpreter, kept him safe from the plots of the Portuguese, and of the kind reception he received at Burhanpur from Mirza Abdurrahim, the emperor’s commander-in-chief in the Deccan. Armed with a letter of favour from the Khan Khanna, Hawkins reached Agra, ‘after much labour, toyle and many dangers’, on 16 April.[32]

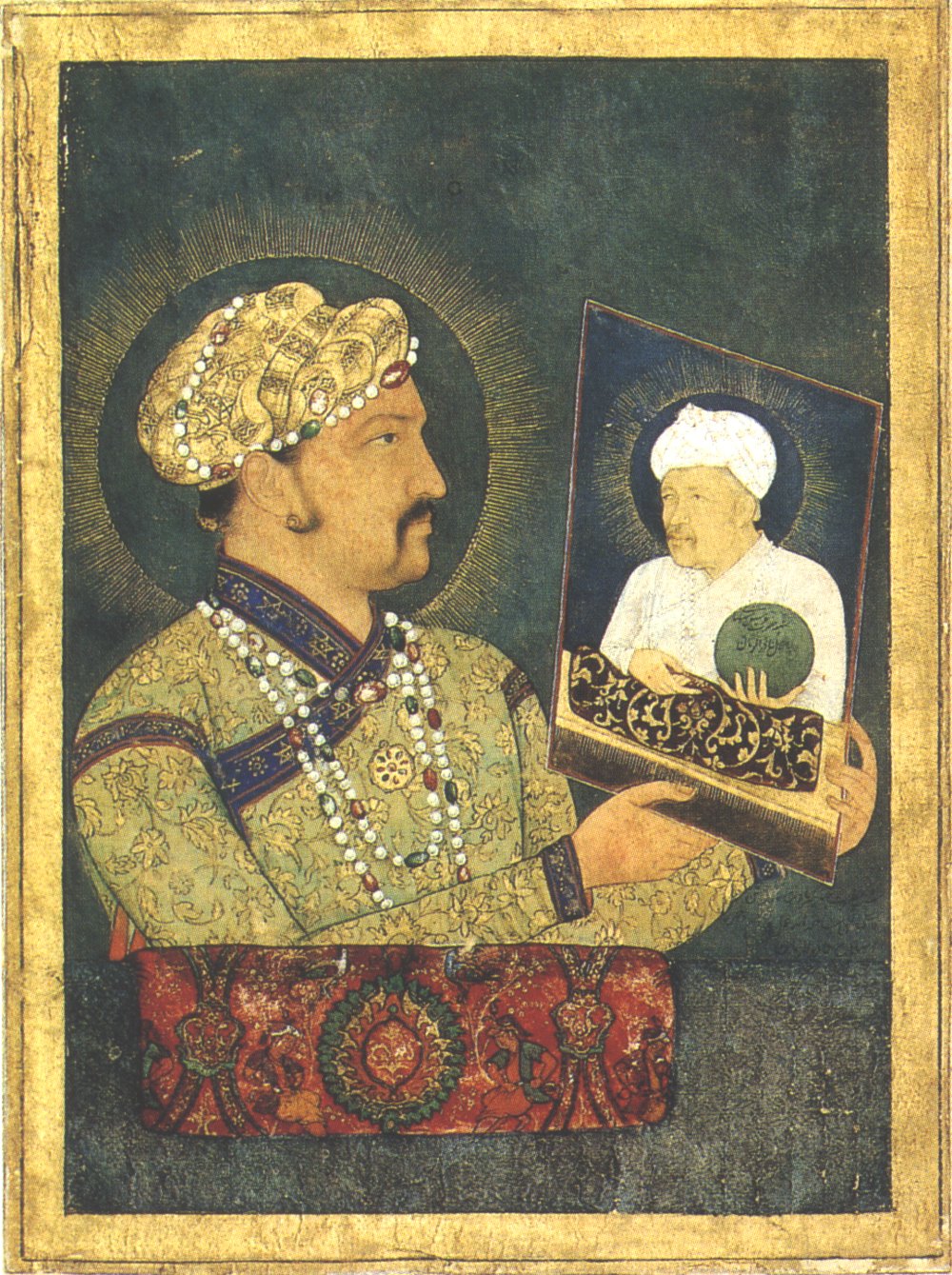

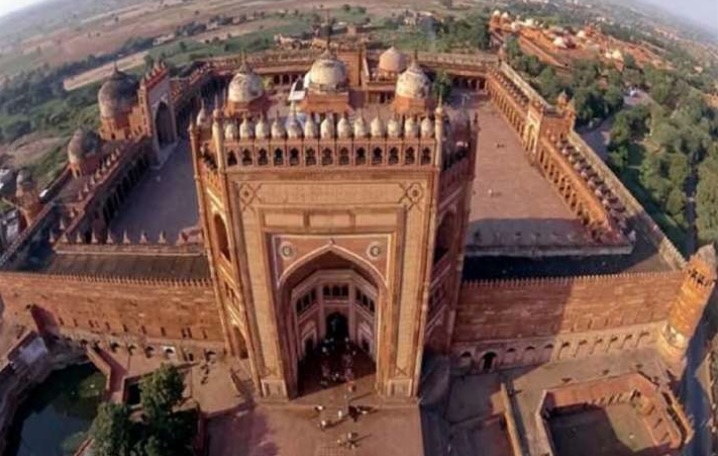

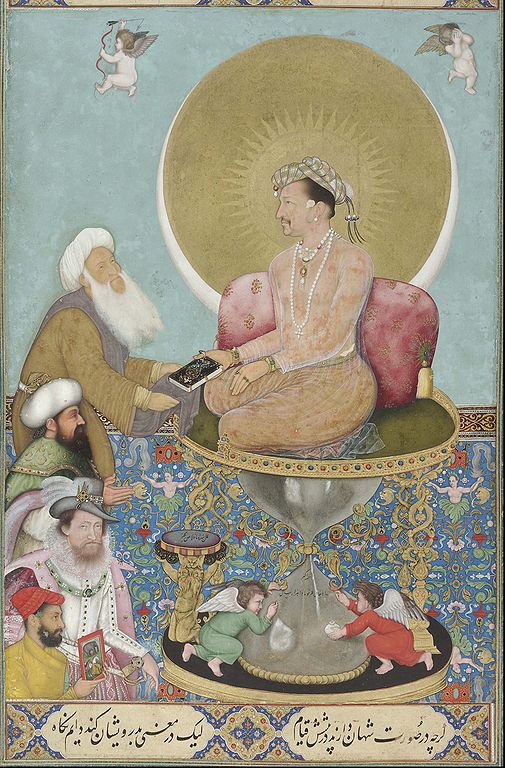

His immediate concern was that Mukarrab Khan’s thieving had left him with little to offer His Majesty as a gift. His plan was to lie low until he could make himself ready. This was a forlorn hope. The new envoy’s presence was quickly detected, and Jahangir – always on the alert for presents – ordered that he be accompanied to court, in state, as the ambassador of another king might expect. Hawkins says that everything was done in such extraordinary haste that he scarcely had time to put on his finery. This will have been profoundly disappointing and, characteristically, Hawkins withheld nothing in his account to the emperor. However, his complaint was received with equanimity. ‘With a most kinde and smiling countenance’, Jahangir gave Hawkins a hearty welcome:

Having His Majesties Letter in my hand, he called me to come neere unto him, stretching downe his hand from the Seate Royall, where he sate in great Majestie something high for to be seene of the people: receiving very kindly the Letter of me. Viewing the Letter a prettie while, both the Seale and the manner of the making of it up, he called for an old Jesuite that was there present to reade it.

As the priest prepared his translation, Jahangir was delighted to receive a résumé from Hawkins in the lingua franca. The more so, when the Jesuit objected that the letter lacked proper respect. Apparently, he had been out of earshot, for he had not expected Hawkins to interject.

If it shall please Your Majestie [he said], these people are our enemies: how can this Letter be ill written, when my King demandeth favour of Your Majestie? he said, it was true.[33]

Jahangir was much taken by Hawkins’ fluency in Turkish, and he called him into his private chamber (the Diwan-i-khas) when the audience was over. Indeed, to the distress of his enemies, Hawkins found himself in great favour. No doubt it was a relief for the emperor to hear from someone who wasn’t a Catholic missionary, of the wonders of the West. Hawkins’ knowledge of the vernacular meant that the distracting attentions of an interpreter could be dispensed with, and, for a time, Hawkins says he had a daily conference:

Both night and day his delight was very much to talke with mee, both of the Affaires of England and other Countries, as also many demands of the West Indies, whereof hee had notice long before, being in doubt if there were any such place till he had spoken with me, who had beene in the Countrey.

The result was that Hawkins was asked to stay at court as resident ambassador. The emperor promised that the arrangement would greatly benefit the English nation, that all Hawkins requested for a factory would follow. In his first year, he would be granted an allowance of £3,200, equivalent to ‘four hundred horse’. Thereafter, it would rise until it came ‘to a thousand horse’. It was a generous offer. Hawkins claims he equivocated before succumbing to the pressure. He then justifies his decision in a manner that reveals the mixed motives of many of the Company’s men:

I trusting upon his promise, and seeing it was beneficiall to my Nation and my selfe, beeing dispossessed of that benefit which I should have reaped, if I had gone to Bantam, and that after halfe a doozen yeeres, Your Worships would send another man of sort in my place, in the meane time, I should feather my Neast, and doe you service; and further perceiving great injuries offered us, by reason the King is so farre from the Ports, for all which causes above specified, I did not thinke it amisse to yeeld unto his request.

In fact, Hawkins was to remain in Agra until the end of 1611.

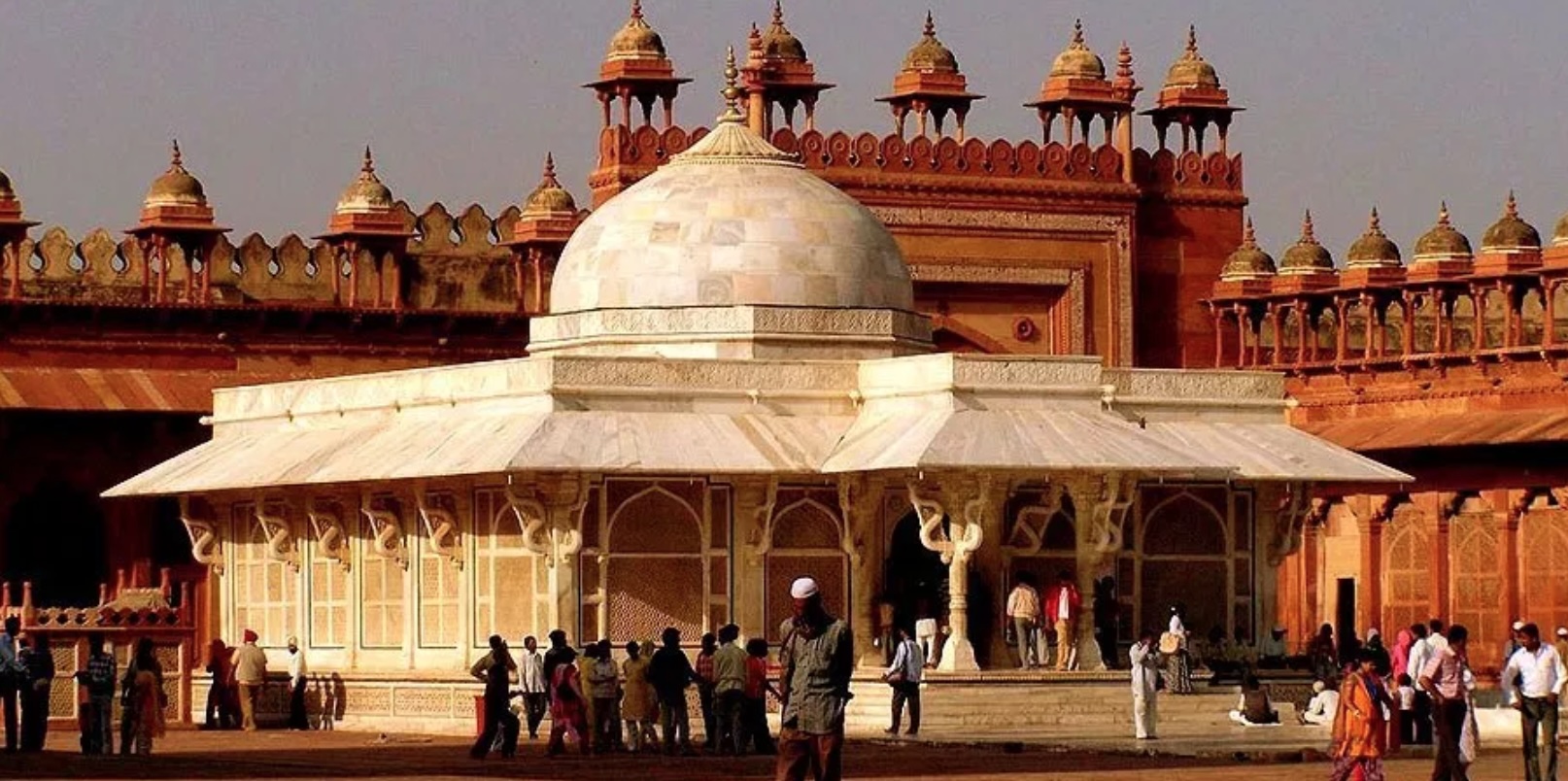

It didn’t stop there. The emperor saw ‘the English Chan’ (so-called ‘because my name was something hard for his pronuntiation’) would be lonely. He needed a wife, someone who might food, and ease his fears of poison. Jahangir implored Hawkins to take ‘a white mayden’ out of his palace. England’s envoy considered how he could turn the offer down without causing offence. ‘In regard she was a Moore,’ he says, ‘I refused, but if so bee there could bee a Christian found, I would accept it.’ Stuck, as he was, in the middle of Mughal India, the odds of a Christian lady turning up appeared extraordinarily low. However, the emperor called to mind the daughter of an Armenian Christian who had found high favour with his father, Akbar. Hawkins explains,

This Captaine died suddenly, and without will, worth a Masse of Money, and all robbed by his Brothers and Kindred, and Debts that cannot be recovered: leaving the Child but only a few Jewels. I, seeing shee was of so honest a Descent, having passed my word to the King, could not withstand my fortunes. Wherefore I tooke her and, for want of a Minister, before Christian Witnesses I marryed her … so ever after I lived content and without feare, she being willing to goe where I went, and live as I lived.[34]

As Hawkins’ favour with Jahangir waxed stronger, the Portuguese did all they could to obtain his overthrow. The Jesuit Pinheiro and his brothers at Surat are accused of ‘setting aside their masses’ in their efforts to dislodge him, and of making the claim, through Mukarrab Khan, that, if the emperor permitted the English to remain, he would lose control of his territories on the coast. Indeed, Jahangir was told that Hawkins planned to assault Diu, the Portuguese enclave on the western side of the Bay of Cambay, once he received shipping support.

Jahangir was unconvinced that a solitary Englishman in Agra could do much harm, and the Portuguese were left to labour ‘like madde Dogges’ to rid themselves of the incubus. The emperor was assailed also by the religious diehards at Court, for whom it grated that ‘a Christian should be so great and neere the King.’ One thing that will have given Hawkins some satisfaction was the temporary fall from grace of Mukarrab Khan. Precipitated by the Englishman’s complaints, a host of other plaintiffs petitioned the emperor for injustices suffered at his hands. He was summoned to court to make an account of himself and, as the emperor rummaged through his stock of goods, Hawkins took pleasure in pointing out those items which he had intended as gifts. One trader complained that,

Mocrebchan had taken his Daughter, saying; she was for the King, which was his excuse, deflowring her himselfe: and afterwards gave her to a Brammen … The matter being examined, and the offence done by Mocerbchan, found to be true, hee was committed to prison, in the power of a great Noble-man: and commandement was given, that the Brammene his privy members should be cut off.

Alas, Mukarrab Khan’s disgrace proved temporary. His allies secured his release, upon a promise that his victims should be restored, and Hawkins says that most were. He was the principal exception.[35]

In Surat, meanwhile, William Finch was struggling to obtain payment for the goods he had sold. In July 1609, he wrote of a circle of bad debts which arose as the result of the seizure, by the Portuguese, of a senior merchant’s ship, which was subsequently wrecked. For a period, Finch made a prisoner of one of his debtors, before accepting some pigs of lead in lieu of cash. As soon as he was released, this merchant he took his entire household and fled, leaving behind a host of other obligations. So, Finch wrote, Hawkins could see ‘the villainy of these people and the little confidence that ought to be reposed in them.’

Instead, noting that English cloth and lead had met with an indifferent market, and that the maintenance of twin establishments at Surat and Agra was a cause of extra expense, Finch was bold enough to suggest that he might be permitted to ‘see the Country’. His plan was to obtain stocks of indigo, and ‘some other drugs’, for the arrival of the next fleet.

Life for Finch must have been a trial. (Already, John Dorchester, who might have provided some company, had died of the flux.) If business was difficult, however, he ended this letter on a note of cautious optimism. Word had reached him of the honours and riches bestowed on the Company’s envoy, which he understood to include a number of village estates (‘aldeas’) near Surat. The news had been received ‘to the great applause of the vulgar sort’, if to the small content of some of the better established. Rumour was that the emperor’s generosity had arisen because Hawkins had given him ‘a small coffer with 7 locks within which were such rare stones that they would lighten the darkest place that it needed no candle.’ Sensibly, Finch had his doubts about this. If were true, he thought, Hawkins had kept his secret very close to his chest. He was, he declared, ‘almost incredulous, as St. Thomas.’ Even so, the news of Hawkins’ reception had done wonders for his reputation. Finch concluded his letter with the recommendation that he take not too much to heart his earlier references to the traders’ ‘mutinous carriages’,

… for your Worship’s letters have put such future hopes of preferments (which is all some gape for) into their heads that I hope they will be honest men.[36]

The Arrival in India of the Ascension, of the Fourth Voyage

Then, on 2 September 1609, almost exactly a year after Hawkins had first landed, a Company ship, the Ascension, was wrecked on the Surat coast.

Commanded by Alexander Sharpeigh, and with John Jourdain as chief merchant, she and her escort, the Union, had left England in March 1608, on the Company’s Fourth Voyage. Its objectives were very similar to those of the Third, but the ships became separated in a storm near the Cape. The Ascension sailed to Aden and Mocha, where she met with mixed success. The Union, however, was detained in Madagascar by troublesome natives. This put the Gulf beyond her reach and, since she also missed the monsoon for India, she sailed to Sumatra, for pepper, and Bantam. Eventually, on her return voyage, she was wrecked a short distance from home, near Cape Finistèrè, in March 1611.[37]

News of Ascension’s approach was received positively by the emperor; so much so that Hawkins used her promise to secure a firman (royal decree) for the building of a factory. However, after they had clambered ashore at Surat, the behaviour of the Ascension’s unruly survivors did the reputation of the English no good. The manner of her wrecking did them no credit either. She had narrowly avoided the shoals once, and the depth beneath her keel was rapidly diminishing for a second time when her master, Phillip Grove, bid ‘let runne’. The Red Dragon, which had twice her burthen, he said, had been in shallower water,

… [but] these words were scarce out of his mouth when we felt the shipp to strike; and the second stroke brake of her ruther. Yett the master would not beleive that shee stroke, till they told him that the ruther was gone. Then he beganne to curse the Companye at home, that had not sought better smithes, and the smithes for puttinge such bad iron on the hooks …

With the turn of the tide, the Ascension’s skiff was crushed against the grounded ship’s side. Into the night and the next day, the carpenters did what they could to repair it but, eventually, some of the crew, doubting for their survival, threatened to make off with the long boat. Sharpeigh chose to pre-empt them and use it to salvage two chests of money. At the sight of this, the crew threatened him with pikes, so he, Jourdain and Robert Coverte ended by clambering out of the Ascension’s rear gallery, Jourdain at one point hanging from the ladder with Coverte clinging to him, ‘soe laden with mony that he could not hardlie goe.’ Jourdain received a ducking, and he was very nearly drowned but, eventually, they, and some seventy-five of the crew, made it into the boat and the patched-up skiff. As everyone helped themselves to what remained of the cash, the boats became so laden that they had just three inches of freeboard. They were fifteen to twenty leagues from shore. They hoisted sail. After narrowly avoiding the Portuguese patrol, and after averting the attempted desertion of those in the skiff, who steered away when the long boat’s mast collapsed, the Englishmen eventually reached the town of Gandivi, where they were welcomed by the governor, refreshed, and sent on to Surat.[38]

There, their behaviour descended into ‘disorder and riot’. The crews developed a taste for ‘a kinde of drinke of the pamita tree called taddy’ and, under its influence, ‘made themselves beasts and soe fell to lewde weomen.’ As some fell sick, and others fell to quarrelling, Thomas Tucker killed a calf by cutting off its tail, ‘a slaughter more then murther in India,’ as William Finch rightly explains. One particular miscreant was the master, Phillip Grove. After Finch had left Surat to join Hawkins at Agra, he let it be known that the stock of lead was his own, and Jourdain his servant. Jourdain was put to much inconvenience before he made the true position clear, though he marvelled that Mukarrab Khan ‘would soe hastelie beleeve such a base drunkard … whoe was never maister of a pigge of lead in his life.’ Understandably, Grove was not popular with the men. He was nearly killed when one of the Ascension’s company ‘gave him a stabb with a knife neere the harte.’ That was before he was discovered making off with three hundred pieces of eight, which had belonged to a crewman who perished from an overdose of opium. Grove ran away to Masulipatam, where we are told he died alone, Jourdain suggesting that a Portuguese may have poisoned him for his money. ‘His end,’ he reports, ‘was very desperate; which shewes that his life was according.’ [39]

After about three weeks at Surat, most of the crew shambled off towards Agra. Avoiding each other’s company, they kept no order, but split into groups of three of four, until their money ran out. Jourdain wrote that it ‘would make a mans eares to tingle to repeate the villanies that was done by them.’ Several fell by the wayside. Some were helped by the Portuguese at Goa, and made their way to Europe. Sharpeigh, who had been dropped by most as leader, followed as far as Burhanpur, where he fell ill. Eventually he reached Agra in safety, but without his money and King James’ letters, which were stolen on the way.[40]

Despite the poor example set by these, his countrymen, for a while Hawkins kept in good odour with the emperor. During afternoon audiences, he wrote, his place was with the nobles ‘within the red Rayle … three steppes higher than the place where the rest stand … among the chiefest of all.’ For two years, he was one of the very few who, after prayers, joined Jahangir for his five cupfuls of liquor, the portion allotted to him by his physicians before, ‘in the height of his drinke he layeth him downe to sleepe.’[41]

A particular highpoint was the occasion, in October 1610, when, at the ceremonial christening of three of Jahangir’s nephews – the sons of his younger brother, Prince Daniyal – the princes were conducted to church by the Christians in the city. Hawkins was at their head, carrying the cross of St. George ‘to the honour of the English nation.’ Jahangir’s motivation here is a little mysterious. At best, however, it was a flirtation. Writing to the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1616, Sir Thomas Roe reported that some believed he intended to prejudice the nephews in the eyes of the Muslim population. This is possible, as they were rivals to his own progeny in the succession. Even more cynically, Roe suggested, with Edward Terry, that it was part of a plan to obtain for the emperor a Portuguese wife. Whatever Jahangir’s reasoning, within five years the Jesuits were reporting, disappointedly, that the princes had ‘rejected the light and returned to their vomit.’ The ceremony marked the peak of Hawkins’ fortunes.[42]

Hawkins’ Fall from Grace and his Return to Surat

That the wreck of the Ascension brought to an end Jahangir’s hopes for the supply of new ‘toys’ did not help Hawkins’ cause. However, John Jourdain, who reached Agra in February 1611, is more critical. He seems to have taken an instant dislike to Hawkins. His contention was that his disgrace arose ‘by his owne folly’.

Firstly, he says, Hawkins was overly zealous in pursuing Mukarrab Khan for recovery of what he owed for his purchases of broadcloth. He adds it was unwise to involve the Chief Vizier, Abul Hasan, who endeavoured – in vain – to persuade Hawkins to accept what he had been offered. Secondly, there was the issue of the Queen Mother’s indigo. She was active in business and William Finch outbid her when she sent a buyer to secure a parcel of it, intended for Mocha. This led to a formal complaint.

Thirdly, there was Hawkins’ taste for alcohol. Jahangir had a taste for it also but, on one of those occasions when he tried to give it up, he issued a command that no one in attendance upon him should have been imbibing beforehand. Hawkins, Jourdain says, was known to be a great drinker, and he offended against the stricture. His offence may have been minor: there is about it the scent of a plot designed to engineer his disgrace. He was caught with the smell of liquor on his breath by one of the palace servants, who had been put on alert by Abul Hasan. (Because he was fasting, the servant had a particularly sensitive nose). Jourdain says that, on being informed of Hawkins’ transgression,

… the Kinge pauzed a little space, and consideringe that he was a stranger, he bid him goe to his howse, and when hee came next he should not drinke. Soe, beeing disgraced in publique, he could not be suffred to come into his accustomed place neere the Kinge; which was the cause that he went not soe often to courte.[43]

All the while, of course, the Portuguese kept up their campaign. They were supported by some of the Gujarati merchants, who argued that nothing the English were likely to produce by way of trade could compensate for what might be lost with Goa. Mukarrab Khan twisted the knife when he explained that he had learned of a particularly fine ruby. It could only be obtained if the Portuguese viceroy were assured the English were being dismissed.

There was a moment of hope when the ruby proved to be a fake and Abul Hasan was replaced as Vizier by a Hawkins’ ally, Ghiyas Beg, the father of Jahangir’s new wife Nur Jahan. Hawkins wrote that Asaf Khan, the vizier’s son, and he were great friends, ‘he having beene often at my house.’ There was also news that another fleet under Sir Henry Middleton (the Company’s Sixth Voyage) was approaching the Gujarat coast. Inspired by the hope of more gifts from the English, and by the present of a ruby ring, which Hawkins produced for the new queen, Jahangir issued a second firman granting permission for a factory and free trade at Surat. No sooner was this done, however, than he was persuaded by one of his nearest favourites, an ally of Mukarrab Khan, to rescind it.

At this, Hawkins declares that his cause was quite overthrown. The English were to be denied the trade he had requested. Even so, he says he was offered the opportunity to remain in Jahangir’s service, on terms that suited him. He gave the idea a moment’s consideration only. He informed the emperor he could accept the one only with the other. A further consultation was held between the emperor and his advisers but, in the end, they stuck to their decision. And so, on 2 November 1611, Hawkins departed Agra, ‘being of a thousand thoughts of which course I were best to take.’

Convinced that no English ship would ever revisit Surat, Finch had by now decided to go overland from Lahore to Aleppo, where he hoped to sell his indigo at a good price. He invited Hawkins to travel with him, and this Hawkins says he might have done but for the impossibility ‘for some causes’ of his travelling through Turkey, ‘especially with a woman’. As it was, there was a falling out between them, Hawkins fearing that Finch meant to abscond with the goods under his charge. Nicholas Ufflet was sent to take his place and the breach became complete. Even when Jourdain informed Finch of Henry Middleton’s approach, he wrote to say he would not return to Agra because he never wished to see Hawkins again. He eventually made his way to Baghdad, where he died after drinking, from a well, water which had been poisoned with ‘a multitude of grasshoppers’. His residual effects were recovered by the Venetian vice-consul at Aleppo, who passed them to the English consul, Bartholomew Haggatt. Aside from his journal, little escaped the clutches of Baghdad’s governor. In writing to the Company, in 1613, Haggatt expressed his deep sorrow at ‘the loss of so proper and so sufficient a countryman.’ He greatly regretted that the valuable estate he had gathered ‘in so great danger, by so great expense of time, and after so long and careful a travail should be eaten up by these currish and tyrannical Turks without any reasonable or sensible pretence alleged’.[44]

Having refused Finch’s offer, Hawkins curried favour with the Jesuits. He applied for a safe conduct from the Portuguese viceroy, for a passage home via Goa and Lisbon. The Fathers, he seemingly imagined, would support his case, if only to be rid of him. Jourdain thought the idea a folly. He told Hawkins that his life in Goa,

… would not bee longe, because hee had too much disputed against the Pope and their religion, and was apt to doe the like againe there if he were urged thereunto, which would cost him his life, and the sooner because of his goods.[45]

By now, Jourdain, who had left Agra with Sharpeigh at the end of July, had learned – from Mukarrab Khan no less – of the anchorage, the ‘Swally Hole’, which was to become England’s first real entrepôt in India. On 14 October, he managed to arrange a rendezvous with Middleton and, after a few days more, he succeeded in guiding him into the new harbour.

From Agra, Hawkins reached Cambay towards the end of the year. He was still minded for Goa. However, he was met by Sharpeigh, who told him of the Swally Hole and persuaded him to accept an invitation from Middleton to sail to England. Hawkins was not reluctant, as it presented him with his only opportunity for getting away with all his goods. He left Cambay on 18 January 1612, and joined Sir Henry and his ships nine days later.[46]

Hawkins with Sir Henry Middleton and John Saris in the Arabian Sea

Sir Henry Middleton had departed London, in March 1610, after the Company had received an indefinite extension to its charter, and an infusion of £80,000 in capital. His vessel, the Trade’s Increase, at a thousand tons, was the largest merchantman yet constructed in an English dockyard. On the Sixth Voyage, she was accompanied by Robert Larkin’s Darling (one hundred tons) and by another vessel fresh off the stocks, Nicholas Downton’s Peppercorn (240 tons). Although little was known of what Hawkins might have achieved, Middleton left England in confident mood.

He took just seven months to reach Socotra, when Keeling had taken eighteen. At Tamore, he was told that the people of Aden and Mocha would be glad to trade, as the Ascension had found, she having sold most of her goods there, and having taken on board a ‘good store’ of ballast, when she passed through. Yet, Sir Henry’s experience in Mocha was little short of disastrous. The Trade’s Increase was too large for the harbour: she ran aground and had to be unloaded to be refloated. Middleton received a hearty welcome as Sharpeigh’s countryman, but once his goods were ashore, the Aga changed his tune. On 28 November, as Middleton and his officers placed stools at the front of their house to watch the sunset, they discovered that the Mochans had their people ‘by the eares’ at the rear. Middleton was knocked out, robbed of his money and rings, and chained by neck with his other men. (Eight were killed.) He was to suffer close to six months’ imprisonment, part of it ‘in a dirty dogge’s kennel under a paire of stairs,’ part of it in Sana’a. He eventually escaped when he was smuggled to his ship in a water butt. [47]

Yet, having obtained freedom for his men and a settlement for his cargo under the threat of a blockade, as he approached Surat, Middleton’s hopes were high once more. What he received on arrival was a letter from Nicholas Bangham, of the Hector, telling him that there was no factory, that he had been sent from Agra to recover overdue debts and that, although he had letters, he dared not send them aboard lest they be intercepted by the Portuguese. When, eventually, he opened Hawkins’ communications, on 5 October, they related,

… the manner of his favouring and dis-favouring by the Great Mogoll, his ficklenesse in granting us Trade, and afterward disallowing the same, giving the Portugals Firmaes against us, contradicting thereby what formerly he had granted to us and our nation.

Two other letters from Finch rounded out the picture, speaking of the capriciousness of the emperor and the hostility of the Portuguese. They advised Middleton in no wise to land his goods, or to hope for trade in those parts.[48]

Middleton soon experienced the Indians’ ‘unconstancie’ at first hand. Mukarrab Khan was up to his usual tricks. He offered good hope of trade, as a way of receiving as many personal concessions and gifts as he could. When they were obtained, he closed the door. It was doubly frustrating that it took until the end of January for this to become plain, as Middleton’s hold was full of goods designed to supply the Indian market. In February 1611, Nicholas Downton wrote to the Company,

Now seeing our King and Nation on every side in disgrace, without favour, and hopeless of future trade, we must depart and add to our former loss the value of our goods yet remaining, fitted for this place and vendible at no other.[49]

On 24 February, off Dabhol, a Council was held to decide whether to aim for Bantam or the Red Sea. Sir Henry explains,

All mens opinions were for the Red-sea, for divers reasons. As first, the putting off of our English goods, and having others in place thereof fitting for our Countrey. Secondly, to take some revenge of the great and unsufferable wrongs and injuries done me by the Turkes there. And the third and the last, but not the least, to save that ship, men and goods (which by way of Massulipatam) wee heard was bound for those parts; which we held unpossible to escape betraying.

The third was a reference to news that another Company fleet (the ships of John Saris’ Eighth Voyage) was headed for the Gulf. But, despite Middleton’s claim to altruism, events were to show he was motivated more by what he might recover for the ships under his command than by what he might do for Saris. This was ever so in the days before subscriptions by investors for individual voyages were replaced by the Company’s First Joint Stock.

Middleton declared he would go to the Red Sea,

… there to meete with such Indian shippes as should be bound thither, and for that they would not deale with us at their owne doores, wee having come so farre with commodities fitting their Countrie, no where else in India vendable: I thought wee should doe our selves some right, and them no wrong, to cause them barter with us, wee to take their Indicoes and other goods of theirs, as they were worth, and they to take ours in liew thereof.

Taken at his word, Middleton was saying the Gujarati merchants were not left out of pocket for their goods (paying ‘as they were worth’). Later, this policy became a matter of bitter contention with Saris, the intent of the latter being (in John Jourdain’s phrase) ‘to take a goose and sticke down a feather.’ The Gujarati merchants would be given little choice in the matter, to be sure, but conceivably Middleton’s greater objectives were to deprive Mocha of its income (out of revenge), and to teach Mukarrab Khan and his ilk that England was as well able to use force to defend her interests as Portugal.[50]

Then, on 2 April, while the fleet stood off Aden, Hawkins brought news that John Saris had gone to the Red Sea before him. Contrary to Middleton’s expectations, he had obtained a pass to trade in Yemen, Aden and Mocha from the Gran Signior in Constantinople. In fact, he had entered Mocha’s harbour confident of a trade and in ‘great hope we might leave a factorye.’

Saris’s fortune was that the governor who had imprisoned Middleton had been ‘cashiered’ when his behaviour had become known. His replacement entertained the English with a lavish dinner, at which was served,

… all sorts of wild fowle, Hennes, Goates, Mutton, Creame, Custards, divers made dishes, and Confections, all served in Vessels of Tinne (different from our Pewter) and made Goblet-fashion with feet, the dishes so placed the one upon the other, that they did reach a yard high as we sate, and yet each dish fit to bee dealt upon without remoove.

Following this, the party retired to an inner chamber where ‘fowre little boyes that attended [the Governor], beeing his buggering boyes’ helped to dress the English in uniforms of cloth of gold and taffeta. In these, they were paraded about the town with the Chief Justice and the Captain of Galleys ‘that the people might take notice of the amitie and friendship that was betwixt us.’

Before long, a caravan reached Mocha from Cairo, as well as two laden ships from India, and Gabriel Towerson was busily engaged negotiating freedom of trade. Saris was thus not greatly impressed when, on 5 April, just he prepared to send two merchants to Sana’a with King James’ letter and present, he received a communication sent by Middleton, informing him that,

… he was come from Surat, and had little or no Trade there. That Captaine Hawkins upon disast was come from Agra, and with his wife was aboord his ship. That he had brought all away from thence, except one man of Captaine Hawkins, which went over Land for England. And that he was come backe to bee revenged of the Turks, wishing our Generall [ie. Saris] to get his people and goods aboord with all speed.

As if to emphasise the point, in his journal Saris juxtaposed notice of the receipt of this letter with an enumeration of the goods being discharged by the two Indian ships that were moored beside him: ‘Lignum Aloes sixtie Kintals, Indico sixe hundred Churles out of both ships, Shashes of all sorts great store, Cinamon of Celon one hundred and fiftie Bahars …’. For a few days, he stayed put. He was told that the three English ships that had appeared in sight of the harbour would be free to trade until the end of the monsoon.[51]

Already, however, Middleton had set his trap. While he, with the Trade’s Increase and Darling, patrolled the Strait of Mandeb, at the southern entrance to the Red Sea, Downton in the Peppercorn was sent to Aden to drive into his net any traders that might be heading there. By 10 April, the effects of his campaign were being felt. The Mochans’ offer was rescinded. Two days later, Saris sailed to the Bay of Assab, at the southern end of what is now Eritrea, for a rendezvous with Middleton.

Saris’ account, in Purchas, says simply that he explained how Sir Henry’s ‘brabbles and jarres’ had imperilled the success of his voyage, both in Mocha and in Surat, and that nothing was concluded between them. As one might have expected, however, this rather understates the heat of their exchange. Each commander had his investors to protect. Saris insisted that Middleton would have to share with him a portion of whatever was extracted from the ships they stopped. Middleton, who had been Saris’ superior on the Second Voyage, and who, in 1612, had been at sea nearly two years longer, was not at all disposed to agree. According to Jourdain, on the second day, they conferred about business until ten at night and ‘did not well concurre together about their affaires.’ Middleton ended by declaring that he would take for himself what he thought fitting and leave Saris to pick over the remains. When Saris threatened to leave and try his fortunes elsewhere, he says the other ‘swore most deepelye that yf I did take that course he would sinke me and sett fire of all such shipps as traded with me.’ Eventually, it was agreed, in principle, that Saris and the ships of the Eighth Voyage would take one-third of the Indians’ goods, and Middleton and his ships two-thirds. They fanned out across the straits to take their prizes. [52]

By 15 May, as Middleton prepared to receive the King of Raheita on the African shore, he was able to inform Downton that he had under his command,

… all the desired ships of India, as the Rehemy of burthen fifteene hundred tunnes, the Hassany of sixe hundred, the Mahumady of one hundred and fiftie tunnes of Surat, the Sallamitae of foure hundred and fiftie tunnes, the Azum Cany, the Sabandar of Moha his ship of two hundred tunnes all of Diu, besides three Mallabar ships; the Cadree of Dabul of foure hundred tunnes, and a great ship of Cananor.

The Hassani, Jourdain notes, was ‘a newe shipp belonging to Abdelasan, Captaine Hawkins friend.’ The Rahimi belonged to Jahangir’s mother and was, according to Downton, ‘the principal mark we aimed at.’ With her in English custody, the emperor would soon come to realise ‘how impatient the subjects of the King of England … are both for the dishonour done to their king, and wrongs to themselves.’[53]

The meeting with the King of Raheita was quite satisfactory. Middleton landed with Saris, Sharpeigh, Downton and Towerson. Hawkins, and the masters and merchants of the fleets also attended. In a demonstration of their power, and as an insurance against treachery, there were, in all, a party of about two hundred armed men. The king,

… came riding downe upon a Cow to visit Sir Henrie and our Generall: he had a Turbant on his head, a piece of Periwinkle shell hanging on his fore-head, in stead of a Jewell, apparelled like a Moore, all naked (saving a Pintado about his loines) attended with an hundred and fiftie men in battaile after their manner, weapond with Darts, Bowes and Arrowes with Sword and Targets … They presented him with divers gifts, and (according to his desire) did give him his lading of Aquavitae, that hee was scarce able to stand; they are Mahometanes, being a blacke hard-favoured people, with curled pates. The King bestowed upon our Generall five Bullockes, and proferred all the assistance he might doe them.[54]

The dispute between the rival captains continued to simmer. Saris was feeling the pressure for other reasons. On 28 April, there had been a near mutiny on the Hector. The crew learned that Sir Henry’s men were being fed fresh meat, and they objected that they were not receiving the same. At one point, the ship’s master, Thomas Fuller, drew his knife on Saris; it took Middleton’s involvement for him to be pacified. (Of Gabriel Towerson, the Hector’s captain, there is no mention.)[55]

There is no clear evidence in the record of what Hawkins thought of all these goings on. Jourdain, however, leaves us in no doubt. He saw ‘many unkinde words’ pass between the two commanders, as they squabbled over their prizes, and as the Gujarati merchants stood by ‘to see their goods parted before their faces.’ He refers to their using ‘very grosse speeches not fittinge for men of their ranke,’ and to their being ‘from this time forward soe crosse thone to the other as yf they had bene enymies.’ On the day of the ceremony with the King of Raheita, Saris says that Middleton,

… gave me good cheere but most vild words; telling me he marveled I would be so sawsie as to stand out with him for the advansing of my voyage; asking me yf I thought myselfe as good a man as he; saing that the King of England knew me not, etc.; with manye other strange words in his chollor …[56]

Jourdain became sufficiently tired of their quarrelling that, when he heard the Darling was being detached from Middleton’s fleet and sent to Sumatra, to collect pepper, he asked to go with her. As a condition of granting this leave, Middleton asked Jourdain to translate into Portuguese a letter he had drafted for Jahangir. In it, he claimed, falsely, that both he and Sharpeigh had been sent on advice received from Hawkins, responding to Jahangir’s firman and favour, that two to three ships should be sent annually. (In fact, Sharpeigh left England a year before Hawkins reached Agra, and Middleton’s instructions make it clear that, at his departure, the Company had no idea of how Hawkins had been received.) Middleton added, falsely, that the gifts he had brought comprised ‘rubies and other the like which our Country of Europe doth afford.’ (The Company had provided thirteen pieces of velvet and some gilt plate only, but Hawkins had since learned that the Portuguese had offered rubies to obtain his dismissal.)

The letter is otherwise a fulsome charge sheet, which concentrates on the ill treatment meted out to the English by Mukarrab Khan, that,

… att Surat, contrary to Macrobians promise and his expectacion, [Hawkins] could not be master of his owne goods, they takinge it from him perforce by order from Macrobean, takinge them at his owne price as he would himself; in the which there were greate losse received by our marchants in the prises, besides manie other injuries done by the said Macrobean to Captaine Hawkins …

… [and that] att my arryvall with the three shipps att the barre of Suratt, beinge laden with the ritch comodities of all sortes of Christians, supposinge to have had good and freindlie enterteinement, butt contrarie wise I was nott suffered to land … havinge beene two yeares att sea since I departed from my countrie … the which was to mee very strannge, seeinge that Your Majestie had granted by firmaa free trade in all your dominions, and they to esteeme command of soe greate a monarke of soe little valewe …

Middleton informed the emperor that, in the circumstances, he had been extremely generous to exchange the Indians’ commodities for goods of his own, when it was in his hands to take them for nought. As a coda, he then issued the following threat:

… that if it shall please you to have a care of your subjects and their goods, that you would bee pleased to send to the Kinges Majestie of England to entreate of peace, before hee send his armadas and men of warre to bee revenged of the wronges that to His Majestie and his subjects hath bene offred within your dominions unjustlie.

The Indian merchants, inevitably, made their complaints but, if Jourdain is an accurate guide, Jahangir was not greatly bothered. It was their own fault, he told them, for dealing roughly with the English at Surat. In paying them for what they had been obliged to surrender at sea, the English ‘had used them better than they deserved.’[57]

The English Fleet Disperses

In August 1612, their thirst for revenge slaked, and with – for the foreseeable future – all hope of participation in the trade between Gujarat and the Red Sea efficiently destroyed, the English dispersed.

Middleton’s men departed for Sumatra and Java, where most succumbed to disease. Middleton himself died, on 24 May 1613, ‘mooste of hartesore’, according to Peter Floris. When John Jourdain reached Bantam from the Moluccas, in August, he saw the huge form of the Trade’s Increase, as it seemed, riding near the shore. Then he realised she was lying on the mud:

Wee hailed them, butt could have noe awnsweare; neither could wee perceive any man sterringe hir ordinance (the most parte thereof mounted). I saluted them with three peeces, but noe awnswere, nor signe of English coulours, neither from the shipp nor from the towne.

Most of her men had died careening her, after she had been weakened by striking a rock off Tiku. Five hundred Javans perished before the first side was sheathed, whereupon hiring others became impossible. The Trade’s Increase was abandoned, and finally burnt by the Javans, at the end of 1614, for fear that she ‘might serve in lieu of a castell.’[58]

Nicholas Downton sailed for England, in February 1613. (He was to return, more profitably, to Surat, in 1614). Saris departed Bantam for Japan, in January. He returned to England, on 27 September 1614, a wealthy man, and died, at the age of sixty-three, in December 1643.

Hawkins’ stay in Bantam was brief. He arrived shortly before Christmas 1612 and departed in January. He sailed on the Thomas, in the company of the Hector, the vessel which had delivered him to Surat four and a half years before. The ships left the Cape of Good Hope, on 21 May 1613, but lost contact with each other. Disease broke out on the Thomas and many of her crew died. She was saved from plunder by some men from Newfoundland, by the Pearl, a private trading vessel that was returning from the East. With her support, she staggered home, eventually arriving in the autumn. Mrs. Hawkins was aboard, but William was not, his fate being to ‘dye on the Irish shoare in his return homewards’. When and how exactly, we are not told. [59]

The verdict of history has not been kind to William Hawkins. In own his time, it is true, Samuel Purchas gave him the support of a protestant patriot. He reserved his criticism for Jahangir who, he says, was ‘so fickle and inconstant, that what hee had solemnly promised for an English factory, was by the Portugals meanes reversed, and againe promised, and againe suspended, and a third time both graunted and disannulled.’ Purchas implied that the forces ranged against Hawkins were almost insuperable: